Abstract

Background and aims

Gambling disorder (GD) presents high rates of suicidality. The combined influences of emotion dysregulation and trait impulsivity are crucially important (albeit understudied) for developing strategies to treat GD and prevent suicide attempts. The aim of this study is to investigate the association between trait impulsivity, emotion dysregulation, and the dispositional use of emotion regulation (ER) strategies with suicidal ideation and psychopathological symptom severity in GD.

Methods

The sample composed of 249 patients with GD (166 with suicidal ideation) who underwent face-to-face clinical interviews and completed questionnaires to assess psychopathological symptoms, impulsive traits, and ER.

Results

Patients with GD who presented suicidal ideation were older and had a later age of GD onset and higher GD severity. Analyses of variance showed higher comorbid symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and trait impulsivity in patients with suicidal ideation. Still, no significant differences were found in the use of ER strategies. SEM analysis revealed that a worse psychopathological state directly predicted suicidal ideation and that both emotion dysregulation and GD severity indirectly increased the risk of suicidal ideation through this state. High trait impulsivity predicted GD severity. Finally, a history of suicide attempts was directly predicted by suicidal ideation.

Conclusions

Patients with GD are at risk of presenting suicidal behaviors. The results of this study revealed the importance of comorbid psychopathology in the occurrence of suicidal ideation and the indirect effect of trait impulsivity and emotion dysregulation on suicidality. Thus, suicidal rates in GD could possibly be reduced by specifically targeting these domains during treatment.

Keywords: gambling disorder, impulsivity, emotion regulation, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, psychopathology

Introduction

Gambling disorder (GD) is characterized by a maladaptive and recurrent pattern of gambling behavior that persists regardless of negative consequences, leading to significant psychological distress and major impacts in day-to-day functioning. GD has a clinical and neurobiological overlap with substance-use disorders (Fauth-Bühler, Mann, & Potenza, 2017; Potenza, 2013); therefore, it was recently recognized as a non-substance-related addiction in the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Of the many factors that can contribute to the development and maintenance of GD, a high level of trait impulsivity is highlighted (Grant & Chamberlain, 2014; Kräplin et al., 2014). Trait impulsivity is a stable personality characteristic, which is defined as the tendency to perform behaviors without premeditation and has premature responses to stimuli that often produce adverse consequences. The UPPS-P [Urgency, Premeditation (lack of), Perseverance (lack of), Sensation Seeking, Positive Urgency] impulsive behavior model is one of the most accepted theoretical approaches for measuring this multifactorial construct and it covers five different dimensions: lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking, as well as positive and negative urgency (Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005).

By definition, individuals with GD often gamble when feeling distressed (APA, 2013; Chamberlain, Stochl, Redden, Odlaug, & Grant, 2017), which is partially explained by emotion regulation (ER) difficulties, but is also highly associated with increased trait impulsivity, especially to negative urgency (a tendency to engage in impulsive behaviors under conditions of negative affect, despite the potentially harmful longer-term consequences; Fauth-Bühler et al., 2017; Savvidou et al., 2017; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001).

ER can be described as the ability by which individuals identify and modulate, either intentionally or unintentionally, the experience and expression of emotions to achieve a desired outcome (Gross, 2007; Rottenberg & Gross, 2006). Some of the strategies used to regulate emotions are adaptive (e.g., reappraisal), whereas others are maladaptive (e.g., suppression; Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). Patients with GD have not only been described as presenting with higher emotional dysregulation, but also to more frequently implement maladaptive strategies to modulate their emotions (Williams, Grisham, Erskine, & Cassedy, 2012).

Emerging evidence indicates that both impulsivity and emotion dysregulation can interact in significant ways that predict addictive behaviors (Fox, Hong, & Sinha, 2008; Gehricke et al., 2007; Granö, Virtanen, Vahtera, Elovainio, & Kivimäki, 2004; Verdejo-García, Lawrence, & Clark, 2008). The fact that these two constructs are very relevant for suicide attempts in different mental health conditions makes it more important to properly explore them in GD (Harris, Chelminski, Dalrymple, Morgan, & Zimmerman, 2018; Rodríguez-Cintas et al., 2018).

The risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts has been reported to be higher in individuals with GD than in the general population (Black et al., 2015). More specifically, the prevalence is found to be as high as 49.2% for suicidal ideation and 18% for suicide attempts in patients with GD, whereas it is reported to be 25.8% and 7.9%, respectively, in participants without GD (Moghaddam, Yoon, Dickerson, Kim, & Westermeyer, 2015). To date, it has been postulated that the main triggers of suicidal ideation and attempts in GD are financial debts, family and social difficulties, legal and employment problems, and the psychological distress or depressive symptoms that usually co-occur with the disorder (Bischof et al., 2016; Ronzitti et al., 2017). In a further attempt to explore how these triggers interact with suicidality, various studies have pinpointed the key role of emotion dysregulation on the emerging negative and overflowing emotions that, together with a perception of coping incapacity, can lead some individuals to see death as the only way out of a specific situation (Neacsiu, Fang, Rodriguez, & Rosenthal, 2018; Shelef, Fruchter, Hassidim, & Zalsman, 2015).

As acknowledged in the previous literature, it is well known that GD presents high rates of suicidality and many suggest the need for more focused studies particularly targeting suicidal ideation. The combined influences of emotion dysregulation and trait impulsivity are crucially important (albeit understudied) for developing strategies to treat GD and prevent suicide attempts in patients suffering from this condition. To our knowledge, no previous research has examined their role in the presence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in GD.

The aim of this study was to explore the association between trait impulsivity, emotion dysregulation, and the dispositional use of two ER strategies (suppression and reappraisal) with present suicidal ideation and/or history of suicide attempts, along with psychopathological symptom severity (both GD severity and global psychopathological state) in an adult sample seeking treatment for GD. We hypothesized that suicidal ideation or history of suicide attempts would be associated with emotional dysregulation, trait impulsivity, and psychopathological symptoms. We also hypothesized that present suicidal ideation would be associated with history of suicide attempts.

Materials and Methods

Sample and procedure

The sample consisted of 249 patients with a diagnosis of GD being treated at the Gambling Disorder Unit within the Department of Psychiatry at Bellvitge University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain), which is a public hospital certified as a tertiary care center with a highly specialized unit for the treatment of addictive behaviors. All participants were consecutively referred through general practitioners or by another mental healthcare professional. Only patients who met DSM-5 (APA, 2013) criteria and sought treatment for GD as their primary mental health concern were included in our sample. Exclusion criteria were: (a) presence of an organic medical illness or neurodegenerative condition, such as Parkinson’s disease or a psychotic disorder; (b) current, or history of, brain injury, neurological disease, or intellectual disabilities. All participants completed the set of questionnaires required for the study and underwent two face-to-face clinical interviews as part of the whole GD assessment. Before initiating outpatient treatment, information was also collected on sociodemographic factors, different clinically relevant variables along with suicidal ideation, and a history of suicide attempts. The presence of suicidal ideation and history of suicide attempts were assessed during a structured face-to-face interview, conducted by a clinical psychologist, where different aspects were covered for gathering complete information about past, recent, and present suicidal ideation and behavior (e.g., directly asking open questions about the desire to live or about the thought of killing themselves and observing verbal and non-verbal communication). Psychological measures were obtained by experienced psychologists, with more than 20 years of GD clinical knowledge. Participants were classified in two groups according to the presence (n = 166) or absence (n = 83) of suicidal ideation. All participants gave written, signed informed consent and received no additional compensation for being part of the study. This study was carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983, and the Committee of the institution involved in the project approved the study.

Table 1 includes the sample description of the sociodemographic and other clinically relevant variables. It also shows the frequency distribution of the data when comparing patients with and without suicidal ideation. With regard to this, the results report some significant statistical differences: patients with suicidal ideation are generally older (mean age = 43.1 vs. 38.8; p = .013, age range comparison), with a later age of GD onset (mean age = 30.9 vs. 26.7; p = .005) and with higher GD severity than the patients without suicidal ideation. Finally, Table 1 also displays the descriptive characteristics and clinical comparisons of the patients with suicidal ideation who reported a history of suicide attempts versus the ones who did not report a history of suicide attempts with no significant results.

Table 1.

Sample description

| Total sample (n = 249) | Suicidal ideation | χ2 | p | Suicide attemptsa | χ2 | p | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 166) | Present (n = 83) | Absent (n = 69) | Present (n = 14) | |||||||||||

| Sociodemographics | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 20 | 8.03 | 12 | 7.23 | 8 | 9.64 | 0.44 | .510 | 6 | 8.70 | 2 | 14.29 | 0.42 | .518 |

| Male | 229 | 91.97 | 154 | 92.77 | 75 | 90.36 | 63 | 91.30 | 12 | 85.70 | ||||

| Origin | ||||||||||||||

| Spain | 234 | 93.98 | 156 | 93.98 | 78 | 93.98 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 65 | 94.20 | 13 | 92.90 | 0.04 | .847 |

| Other country | 15 | 6.02 | 10 | 6.02 | 5 | 6.02 | 4 | 5.80 | 1 | 7.10 | ||||

| Civil status | ||||||||||||||

| Single | 129 | 51.81 | 94 | 56.63 | 35 | 42.17 | 5.31 | .070 | 28 | 40.58 | 7 | 50.00 | 0.43 | .806 |

| Married/partner | 92 | 36.95 | 57 | 34.34 | 35 | 42.17 | 30 | 43.48 | 5 | 35.70 | ||||

| Separated/divorced | 28 | 11.24 | 15 | 9.04 | 13 | 15.66 | 11 | 15.94 | 2 | 14.30 | ||||

| Studies level | ||||||||||||||

| Primary | 136 | 54.62 | 90 | 54.22 | 46 | 55.42 | 0.10 | .950 | 36 | 52.17 | 10 | 71.40 | 1.82 | .402 |

| Secondary | 90 | 36.14 | 60 | 36.14 | 30 | 36.14 | 27 | 39.13 | 3 | 21.40 | ||||

| University | 23 | 9.24 | 16 | 9.64 | 7 | 8.43 | 6 | 8.70 | 1 | 7.10 | ||||

| SES | ||||||||||||||

| Mean high to high | 21 | 8.43 | 14 | 8.43 | 7 | 8.43 | 1.82 | .612 | 6 | 8.70 | 1 | 7.10 | 1.76 | .624 |

| Mean | 22 | 8.84 | 16 | 9.64 | 6 | 7.23 | 6 | 8.70 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Mean low | 106 | 42.57 | 74 | 44.58 | 32 | 38.55 | 27 | 39.13 | 5 | 35.70 | ||||

| Low | 100 | 40.16 | 62 | 37.35 | 38 | 45.78 | 30 | 43.48 | 8 | 57.10 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 82 | 32.93 | 48 | 28.92 | 34 | 40.96 | 3.64 | .057 | 27 | 39.13 | 7 | 50.00 | 0.57 | .451 |

| Employed | 167 | 67.07 | 118 | 71.08 | 49 | 59.04 | 42 | 60.87 | 7 | 50.00 | ||||

| Gambling variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T | p | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T | p |

| Age (years) | 40.25 | 12.82 | 38.83 | 13.33 | 43.11 | 11.27 | 2.51 | .013 | 43.09 | 11.89 | 43.21 | 7.80 | 0.04 | .970 |

| GD Onset (years) | 28.12 | 11.28 | 26.71 | 10.64 | 30.93 | 12.04 | 2.82 | .005 | 31.07 | 12.24 | 30.21 | 11.38 | 0.25 | .809 |

| GD Duration (years) | 5.69 | 5.71 | 5.50 | 5.69 | 6.08 | 5.76 | 0.76 | .445 | 6.26 | 6.04 | 5.21 | 4.21 | 0.62 | .539 |

| DSM-5 total criteria | 7.14 | 1.67 | 6.97 | 1.75 | 7.49 | 1.46 | 2.35 | .020 | 7.58 | 1.41 | 7.07 | 1.69 | 1.19 | .237 |

| Substance variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T | p | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T | p |

| Tobacco: cigarettes-day | 11.01 | 11.10 | 10.26 | 10.69 | 12.52 | 11.79 | 1.51 | .130 | 13.07 | 12.14 | 9.79 | 9.84 | 0.95 | .345 |

| Alcohol: AUDIT total | 4.68 | 5.76 | 4.34 | 4.89 | 5.36 | 7.17 | 1.31 | .189 | 5.52 | 7.38 | 4.57 | 6.24 | 0.45 | .654 |

| Drugs: DUDIT total | 2.59 | 6.03 | 2.18 | 5.45 | 3.41 | 7.01 | 1.52 | .131 | 3.00 | 6.83 | 5.43 | 7.78 | 1.18 | .240 |

Note. Bold values represent significant results (.05 level). SD: standard deviation; SES: socioeconomic status; GD: gambling disorder; AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; DUDIT: Drug Use Disorders Identification Test.

Descriptive for the subsample of participants who reported presence of suicidal ideation.

Measures

GD diagnosis and GD severity. Patients were assessed using the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013) through a face-to-face clinical interview. Demographic and social variables related to gambling were also measured.

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1994) is a 90-item questionnaire that evaluates psychopathological symptoms. It measures nine primary symptom dimensions: somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. It also includes three global indices: a Global Severity Index, designed to measure overall psychological distress; a Positive Symptom Distress Index, to measure the symptom intensity; and a Positive Symptom Total, which reflects self-reported symptoms. The Spanish validation of this questionnaire presents an internal consistency of 0.75 (González de Rivera, de las Cuevas, Rodríguez Abuín, & Rodríguez Pulido, 2002). Internal consistency for all of the subscales in this study sample ranged from 0.802 to 0.981.

UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Whiteside et al., 2005) is a 59-item questionnaire to assess five different features of impulsive traits: lack of perseverance, lack of premeditation, sensation seeking, negative urgency, and positive urgency. The UPPS-P has satisfactory psychometric properties (Cyders & Smith, 2008b) that have also been demonstrated in its Spanish adaptation (Verdejo-García, Lozano, Moya, Alcázar, & Pérez-García, 2010). The α values for the different UPPS-P scales in our sample ranged from .77 to .92.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Schreiber, Grant, & Odlaug, 2012), Spanish validation (Hervás & Jódar, 2008; Wolz et al., 2015), is a 36-item self-report scale that assesses relevant difficulties in ER on six subscales: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse-control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to ER strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. The measure yields a total score as well as scores on the six subscales. Higher scores indicate greater problems with ER. Cronbach’s α for the total score in the present study was .93.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, Spanish version (ERQ; Cabello, Salguero, Fernández-Berrocal, & Gross, 2013), is a 10-item questionnaire to assess the respondents’ tendency to implement two ER strategies: reappraisal and emotional suppression. This questionnaire has shown adequate validity and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .75, .71, respectively). For this study, it shows a Cronbach’s α of .73 for the suppression scale, and .75 for the reappraisal scale.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Delgado, 1996; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la fuente, & Grant, 1993) is a 10-item screening questionnaire for hazardous alcohol consumption. It comprises three questions on the amount and frequency of drinking, three questions on alcohol dependence, and four questions on problems caused by alcohol. A score of 8 or more is considered to indicate harmful alcohol use, and a score of 12 or more in women (15 or more in men) is likely to indicate alcohol dependence. This questionnaire has shown adequate validity in Spanish samples.

Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (Berman, Bergman, Palmstierna, & Schlyter, 2003) is a 11-item self-administered instrument to identify non-alcohol drug use patterns and related problems in individuals likely to meet criteria for a substance dependence diagnosis. The total score can range from 0 to 44 (as a result of the sum of the 11 items scored from 0 to 4); higher scores are indicative of more severe drug problem. The first nine items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, and the last two are scored on 3-point scales (values of 0, 2, and 4).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata15 (StataCorp, 2017) for Windows. Comparisons between groups (i.e., presence/absence of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts) were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and adjusted for the covariates age and sex. The effect sizes for the mean comparisons were based on Cohen’s d coefficients (low effect size was considered for |d| > .20, moderate for |d| > .50, and large for |d| > .80; Kelley & Preacher, 2012). Due to the risk of type-I error when using multiple statistical comparisons, Finner’s correction was implemented. This method is classified within the familywise error rate stepwise procedures and it is described to be more powerful than the classical Bonferroni correction (Finner, 1993).

Pathway analysis, developed through structural equation modeling (SEM), analyzed the underlying mechanisms between emotional dysregulation (DERS), trait impulsivity (UPPS-P), psychopathology (SCL-90-R), GD severity (the number of DSM-5 criteria met out of a maximum of nine), and the presence of suicidal ideation and history of suicide attempts. Given the large number of variables and the statistical impact that this can have on the analysis, the grade of emotion dysregulation was based on the DERS-total score and on the ERQ-suppression strategy; finally, a latent variable measuring impulsivity was defined based on all the UPPS-P subscales. The SEM was obtained using the maximum likelihood as estimation, and the overall goodness-of-fit was evaluated through the standard statistical indices (Barrett, 2007): root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The adequate goodness-of-fit of the model was considered with RMSEA < 0.10, TLI > 0.9, CFI > 0.9, and SRMR < 0.1. In this study, the χ2 test was not considered as a fitting measure due to the strong dependence of this statistical test on sample size. That is, in a small sample size with low statistical power, it may fail to reject inappropriate models, and in a large sample size it may reject appropriate models due to the excess of statistical power.

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The University Hospital of Bellvitge Ethics Committee of Clinical Research approved the study. All subjects were informed about the study and all provided informed consent for participation.

Results

Comparison of the clinical profiles between the groups

Table 2 includes the results of the ANOVA (adjusted by the covariates sex and age) for impulsivity, psychopathological symptoms, and emotional dysregulation. When comparing patients with and without suicidal ideation, differences emerged for some of the trait impulsivity features (namely lack of perseverance and positive and negative urgency) for psychopathological symptoms and also for emotion dysregulation. All of these indices were higher for the patients with suicidal ideation. No differences were found regarding ER strategies (i.e., suppression and reappraisal). With regard to the subsample of patients with suicidal ideation, no differences emerged in any of the clinical measures when comparing patients with and without history of suicide attempts.

Table 2.

Comparison of the clinical profiles between the groups of the study: ANOVA adjusted by the covariates participants’ sex and age

| α | Total sample (n = 249) | Subsample: with suicidal ideation (n = 83) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation: no (n = 166) | Suicidal ideation: yes (n = 83) | F(1, 245) | p | |d| | Suicide attempts: no (n = 69) | Suicide attempts: yes (n = 14) | F(1, 79) | p | |d| | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||||

| Impulsivity (UPPS-P) | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of premeditation | .853 | 24.33 | 6.45 | 25.61 | 6.18 | 2.22 | .138 | 0.20 | 25.50 | 6.45 | 24.98 | 6.18 | 0.08 | .963 | 0.08 |

| Lack of perseverance | .769 | 21.40 | 5.22 | 23.35 | 5.74 | 7.02 | .009 | 0.36 | 23.31 | 5.22 | 23.23 | 5.74 | 0.00 | .612 | 0.01 |

| Sensation seeking | .866 | 27.92 | 9.19 | 27.20 | 7.74 | 0.41 | .520 | 0.08 | 26.70 | 9.19 | 25.63 | 7.74 | 0.26 | .828 | 0.13 |

| Positive urgency | .924 | 30.27 | 10.05 | 33.11 | 9.69 | 4.47 | .036 | 0.29 | 32.96 | 10.05 | 33.57 | 9.69 | 0.05 | .771 | 0.06 |

| Negative urgency | .807 | 31.48 | 7.17 | 33.36 | 6.10 | 4.12 | .044 | 0.28 | 33.34 | 7.17 | 32.81 | 6.10 | 0.08 | .903 | 0.08 |

| Psychopathology (SCL-90-R) | |||||||||||||||

| Somatization | .904 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 1.20 | 0.84 | 22.92 | <.001 | 0.62a | 1.22 | 0.68 | 1.19 | 0.84 | 0.01 | .871 | 0.04 |

| Obsessive–compulsive | .890 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 1.43 | 0.81 | 20.94 | <.001 | 0.62a | 1.45 | 0.76 | 1.41 | 0.81 | 0.03 | .766 | 0.05 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | .872 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 1.27 | 0.81 | 17.56 | <.001 | 0.56a | 1.26 | 0.75 | 1.33 | 0.81 | 0.09 | .768 | 0.09 |

| Depressive | .911 | 1.30 | 0.90 | 1.96 | 0.74 | 32.01 | <.001 | 0.80a | 1.96 | 0.90 | 2.02 | 0.74 | 0.09 | .887 | 0.08 |

| Anxiety | .888 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 1.30 | 0.79 | 21.64 | <.001 | 0.62a | 1.31 | 0.71 | 1.27 | 0.79 | 0.02 | .878 | 0.04 |

| Hostility | .846 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 1.30 | 0.87 | 23.01 | <.001 | 0.64a | 1.29 | 0.76 | 1.25 | 0.87 | 0.02 | .224 | 0.05 |

| Phobic anxiety | .809 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 13.61 | <.001 | 0.51a | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 1.50 | .615 | 0.43 |

| Paranoia | .802 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 10.91 | .001 | 0.50a | 1.17 | 0.73 | 1.05 | 0.83 | 0.26 | .793 | 0.16 |

| Psychotic | .846 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 1.17 | 0.73 | 20.58 | <.001 | 0.61a | 1.16 | 0.67 | 1.22 | 0.73 | 0.07 | .885 | 0.08 |

| GSI | .981 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 1.35 | 0.65 | 31.62 | <.001 | 0.76a | 1.36 | 0.62 | 1.38 | 0.65 | 0.02 | .538 | 0.04 |

| PST | .981 | 41.47 | 21.46 | 56.99 | 18.78 | 30.58 | <.001 | 0.77a | 57.88 | 21.46 | 54.43 | 18.78 | 0.38 | .310 | 0.17 |

| PSDI | .981 | 1.74 | 0.52 | 2.07 | 0.54 | 22.21 | <.001 | 0.63a | 2.05 | 0.52 | 2.21 | 0.54 | 1.04 | .473 | 0.30 |

| Emotional dysregulation | |||||||||||||||

| DERS Non-acceptance | .875 | 16.32 | 5.78 | 19.14 | 5.38 | 10.74 | .001 | 0.50a | 19.43 | 6.78 | 18.29 | 5.38 | 0.52 | .234 | 0.19 |

| DERS Goal-directed behavior | .804 | 13.43 | 4.62 | 15.20 | 4.90 | 7.59 | .006 | 0.37 | 14.85 | 4.62 | 16.59 | 4.90 | 1.44 | .423 | 0.37 |

| DERS Impulse-control difference | .855 | 12.84 | 5.46 | 15.79 | 5.64 | 15.36 | <.001 | 0.53a | 15.47 | 5.46 | 16.82 | 5.64 | 0.65 | .858 | 0.24 |

| DERS Lack of emotional awareness | .722 | 16.10 | 4.52 | 17.37 | 4.09 | 4.54 | .034 | 0.30 | 17.37 | 4.52 | 17.59 | 4.09 | 0.03 | .618 | 0.05 |

| DERS Emotion regulation | .879 | 18.01 | 7.34 | 21.69 | 7.00 | 13.95 | <.001 | 0.51a | 21.61 | 7.34 | 22.65 | 7.00 | 0.25 | .202 | 0.15 |

| DERS Emotional clarity | .758 | 11.13 | 3.92 | 12.30 | 4.00 | 4.72 | .031 | 0.30 | 12.06 | 3.92 | 13.56 | 4.00 | 1.66 | .473 | 0.38 |

| DERS Total score | .930 | 87.83 | 23.74 | 101.5 | 21.94 | 18.63 | <.001 | 0.60a | 100.8 | 23.74 | 105.5 | 21.94 | 0.52 | .645 | 0.21 |

| ERQ Suppression scale | .734 | 3.82 | 1.46 | 4.08 | 1.25 | 1.92 | .167 | 0.19 | 4.09 | 1.46 | 4.26 | 1.25 | 0.21 | .238 | 0.13 |

| ERQ Reappraisal scale | .747 | 4.31 | 1.17 | 4.32 | 1.12 | 0.00 | .949 | 0.01 | 4.36 | 1.17 | 3.96 | 1.12 | 1.41 | .251 | 0.34 |

Note. p value includes Finner’s correction for multiple statistical comparisons. Bold values represent significant comparison (.05 level). SD: standard deviation; α: Cronbach’s α in the sample; |d|: Cohen’s-d coefficient (absolute value); UPPS-P: Impulsive Behavior Scale; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; DERS: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; ERQ: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; GSI: Global Severity Index; PST: Positive Symptom Total; PSDI: Positive Symptom Distress Index.

Effect size ranging from moderate (|d| > 0.50) to high (|d| > 0.80).

Pathways analysis [structural equation modeling (SEM)]

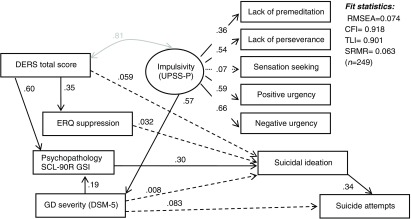

Figure 1 contains the path diagram of the SEM, the standardized coefficients, and the fit statistics. This model is adjusted by the covariates participants’ sex and age. Supplementary Table S1 contains the correlation-matrix for the variables of the study and gives some extra information about the studied variables and the ones included in the SEM. Supplementary Table S2 contains the complete results for the model (standardized parameters, including the specific coefficients, the standard errors, the significant tests, and the 95% confidence interval for the coefficients). The SEM goodness-of-fit is adequate (all the statistics are into the adequate range: RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.901, and SRMR = 0.063). The results indicate that suicidal ideation is directly predicted by worse psychopathological state. The DERS-total score and the GD severity indirectly increased the risk for suicidal ideation through the psychopathological state (which achieves the role of a mediation variable): high emotional dysregulation and high GD severity predicted worse psychopathological state, which is a risk factor for suicidal ideation. High trait impulsivity is related to high GD severity, which is a predictor of worse psychopathological state, and this last measure is a predictor of suicidal ideation. Finally, a history of suicide attempts is directly predicted by suicidal ideation, therefore indirectly associated with the other reported variables (namely GD severity, emotional dysregulation, and impulsivity) through suicidal ideation.

Figure 1.

Path diagram including the standardized coefficients for the SEM. Note. Results adjusted by sex and age. Normal arrow: significant coefficient (.05 level); Dashed arrow: non-significant coefficient; Gray: covariance parameter; DERS: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; ERQ: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; UPPS-P: Impulsive Behavior Scale; SCL-90R: Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; GSI: Global Severity Index; GD: gambling disorder; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; CFI: Bentler’s comparative fit index; TLI: Tucker–Lewis index; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual

Discussion

This study explored psychopathological symptoms, trait impulsivity, emotion dysregulation, and the dispositional use of two ER strategies (i.e., suppression and reappraisal) in an adult sample of consecutive treatment-seeking patients diagnosed with GD. We specifically compared patients who reported suicidal ideation (with or without a history of suicide attempts) with those who did not, in order to identify the factors that best explained the presence of suicidal ideation and its impacts on suicide attempts.

Consistent with previous studies exploring suicidal ideation in clinical populations with mental health conditions, the patients who reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts also most frequently presented higher psychopathological symptoms and higher disorder severity (Chesney, Goodwin, & Fazel, 2014; Furczyk & Thome, 2014; Poorolajal, Haghtalab, Farhadi, & Darvishi, 2016; Qin, Hawton, Mortensen, & Webb, 2014). There is accumulated evidence suggesting that in patients with GD, a higher suicide risk would be most likely associated with affective comorbid symptoms and other external difficulties (such as marital difficulties, financial debts, etc.), than with the GD symptoms by themselves (Maccallum & Blaszczynski, 2003; Ronzitti et al., 2017; Wong, Kwok, Tang, Blaszczynski, & Tse, 2014). Previous studies have also identified that an earlier age of onset is associated with higher GD severity and more comorbidities (Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2016). However, in this study, patients with suicidal ideation presented higher severity and more comorbid symptoms, despite being of an older age and presenting a later GD onset than those patients without suicidal ideation. This leads us to hypothesize that, in patients with suicidal ideation, a later GD onset does not have a protective effect for gambling severity, which could be explained by higher cognitive dissonance between the patient values and the gambling behavior at an older age and to factors associated with suicidal ideation. Moreover, Granero et al. (2014) explored age as a moderator of gambling pathology and observed that the older the patient, the higher the comorbid health problems and the emotional distress they presented (measured by means of the SCL-90-R). Bearing these findings in mind, gambling behaviors in older adults could be associated with a need to ameliorate negative feelings and to cope with stressful situations related to older age (Sauvaget et al., 2015; Subramaniam et al., 2015).

The findings of this study also revealed higher trait impulsivity (specifically lack of perseverance and positive and negative urgency) and worsened emotion dysregulation in the patients with GD and suicidal ideation when compared to those without suicidal ideation. However, contrary to our initial hypothesis, there were no differences in the ER strategies implemented by these two groups. Numerous studies have presented evidence on the presence of high impulsivity and emotion dysregulation in patients with GD (Schreiber et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2012) when compared with healthy control groups; being negative urgency, the trait impulsivity feature most robustly associated with GD severity and a worse treatment response (Verdejo-García et al., 2008). In fact, a recent study conducted with patients presenting substance-use problems has already confirmed that both the negative urgency and the lack of premeditation were the features that presented less change after psychotherapy (Hershberger, Um, & Cyders, 2017).

The role of emotion dysregulation and trait impulsivity in suicidality has not previously been explored in GD, but it is known from previous literature on other psychiatric populations that both variables are highly associated with suicide ideation (Lynam, Miller, Miller, Bornovalova, & Lejuez, 2011; Neacsiu et al., 2018; Swann et al., 2005). The results of this study expand previous clinical knowledge and reveal the importance of these two variables in the suicidality risk of patients with GD. On the contrary, despite being known that suicide ideation and attempts are associated with lower use of reappraisal and higher use of suppression strategies in different psychiatric populations (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010), this seems not to be the case in GD patients. The dispositional use of less adaptive strategies (namely suppression) and over reappraisal has been associated with GD (Navas et al., 2017), and previous studies have proposed that the gambling behavior could act as a maladaptive strategy to regulate emotions in some of the patients (Grall-Bronnec et al., 2012). Yet, the present results uphold some interesting evidence and lead us to postulate that individuals with GD already have a lack of adaptive strategies and it is the severity of emotion dysregulation and trait impulsivity, which indirectly make them more prone to suicide ideation.

Finally, in the present sample, trait impulsivity highly correlates with emotion dysregulation, and both variables had important roles when indirectly predicting suicidality through the presence of psychopathological symptoms and GD severity. These findings are of special interest as they result in a comprehensive and controlled GD model that integrates variables known to be involved in the risk of suicidality (i.e., comorbid psychopathology) with other unexplored but still suicide-relevant variables (namely emotion dysregulation and trait impulsivity). Patients who were more impulsive by trait also presented higher GD severity (a predictor of psychopathology; Aragay et al., 2018; Cyders & Smith, 2008a; Hodgins, Mansley, & Thygesen, 2006), probably due to the fact that addictive behaviors start from an impulsive driven urge, and impulsivity is a established high-risk factor for developing the disorder (Auger, Lo, Cantinotti, & O’Loughlin, 2010; Canale, Vieno, Griffiths, Rubaltelli, & Santinello, 2015). If the severity of the disorder is higher, there are greater impacts on personal and social factors, thus enhancing psychopathological symptoms. Similarly, higher emotion dysregulation predicted psychopathological symptoms, possibly because patients with GD tend to experience very intense emotions as part of the negative impacts of gambling, making it even more difficult to not suffer from higher psychopathological symptoms if already presenting ER difficulties. It should be noted that a higher emotion dysregulation predicted suppression, which is a maladaptive strategy (Aldao et al., 2010) that patients could be implementing in an attempt to unsuccessfully decrease the intense emotions that they experience (Navas et al., 2017).

This study has some limitations that should be taken into consideration. The main weakness was that history of suicide attempts was retrospectively explored in a cross-sectional design; thus, future studies should test how present suicidal ideation and its associations with emotion dysregultaion and impulsivity interact in a prospective study. In addition, all the individuals of our sample were voluntarily attending GD treatment and self-report measures were used that may be biased by desirability or insight. For this reason, the generalizability of our results to other populations should be tested in future studies. Finally, a constrained sample of patients reported a history of suicide attempts; thus, the results obtained regarding this subgroup should be considered with caution.

In conclusion, this study provides greater empirical understanding of the implications of trait impulsivity, emotion dysregulation, and comorbid psychopathological symptoms in GD. On the whole, the findings suggest that patients with GD who present higher trait impulsivity and higher difficulties regulating emotions are more prone to present suicidal ideation and a history of suicide attempts through the presence of worse GD severity and higher psychopathology. Thus, it strikes as highly relevant that when treating patients with GD a special emphasis is placed on targeting emotion dysregulation and trait impulsivity features, as they could be enhancing psychopathological symptoms and as such be indirectly associated with suicidality.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: Financial support was received through the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (grant PSI2011-28349 and PSI2015-68701-R). FIS PI14/00290, FIS PI17/01167, and 18MSP001-2017I067 received aid from the Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. CIBER Fisiología Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERobn) and CIBER Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), both of which are initiatives of ISCIII. GM-B is supported by a predoctoral AGAUR grant (2018 FI_B2 00174), co-financed by the European Social Fund, with the support of the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya. TM-M and CV-A are supported each one by a predoctoral Grant of the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU16/02087 and FPU16/01453).

Authors’ contribution

SJ-M, FF-A, NM-B, and JMM contributed to the development of the study concept and design. RG performed the statistical analysis. SJ-M, NM-B, TM-M, and RG aided with our interpretation of data and the writing of the manuscript. TM-M, CV-A, JS-G, ADP-G, GMB, NA, and MG-P collected the data. FF-A, JMM, CV-A, JS-G, ADP-G, GM-B, NA, and MG-P revised the manuscript and provided substantial comments. SJ-M, FF-A, and JMM obtained funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2010). Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(10), 974–983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Schweizer S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aragay N., Barrios M., Ramirez-Gendrau I., Garcia-Caballero A., Garrido G., Ramos-Grille I., Galindo Y., Martin-Dombrowski J., Vallès V. (2018). Impulsivity profiles in pathological slot machine gamblers. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 83, 79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger N., Lo E., Cantinotti M., O’Loughlin J. (2010). Impulsivity and socio-economic status interact to increase the risk of gambling onset among youth. Addiction, 105(12), 2176–2183. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 815–824. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berman A. H., Bergman H., Palmstierna T., Schlyter F. (2003). The Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) Manual. Stockholm, Sweden: Karolinska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof A., Meyer C., Bischof G., John U., Wurst F. M., Thon N., Lucht M., Grabe H. J., Rumpf H.-J. (2016). Type of gambling as an independent risk factor for suicidal events in pathological gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 263–269. doi: 10.1037/adb0000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D. W., Coryell W., Crowe R., McCormick B., Shaw M., Allen J. (2015). Suicide ideations, suicide attempts, and completed suicide in persons with pathological gambling and their first-degree relatives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(6), 700–709. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello R., Salguero J. M., Fernández-Berrocal P., Gross J. J. (2013). A Spanish adaptation of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 29(4), 234–240. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canale N., Vieno A., Griffiths M. D., Rubaltelli E., Santinello M. (2015). How do impulsivity traits influence problem gambling through gambling motives? The role of perceived gambling risk/benefits. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 813–823. doi: 10.1037/adb0000060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain S. R., Stochl J., Redden S. A., Odlaug B. L., Grant J. E. (2017). Latent class analysis of gambling subtypes and impulsive/compulsive associations: Time to rethink diagnostic boundaries for gambling disorder? Addictive Behaviors, 72, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney E., Goodwin G. M., Fazel S. (2014). Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 153–160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. (2008a). Clarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. (2008b). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado J. M. M. (1996). Validación de los cuestionarios breves: AUDIT, CAGE y CBA para la detección precoz del síndrome de dependencia de alcohol en Atención Primaria [Validation of the short questionnaires: AUDIT, CAGE and CBA for the early detection of alcohol dependence syndrome in primary care] (Doctoral dissertation). Universidad de Cádiz. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. (1994). SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas [SCL-90-R. 90-Symptoms Questionnaire]. Madrid, Spain: TEA ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Fauth-Bühler M., Mann K., Potenza M. N. (2017). Pathological gambling: A review of the neurobiological evidence relevant for its classification as an addictive disorder. Addiction Biology, 22(4), 885–897. doi: 10.1111/adb.12378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finner H. (1993). On a monotonicity problem in step-down multiple test procedures. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88(423), 920–923. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1993.10476358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. C., Hong K. A., Sinha R. (2008). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 33(2), 388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furczyk K., Thome J. (2014). Adult ADHD and suicide. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 6(3), 153–158. doi: 10.1007/s12402-014-0150-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke J.-G., Loughlin S., Whalen C., Potkin S., Fallon J., Jamner L., Belluzzi J. D., Leslie F. (2007). Smoking to self-medicate attentional and emotional dysfunctions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9(Suppl. 4), 523–536. doi: 10.1080/14622200701685039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González de Rivera J. L., de las Cuevas C., Rodríguez Abuín M., Rodríguez Pulido F. (2002). SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas. Manual. Madrid, Spain: TEA ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Grall-Bronnec M., Wainstein L., Feuillet F., Bouju G., Rocher B., Vénisse J.-L., Sébille-Rivain V. (2012). Clinical profiles as a function of level and type of impulsivity in a sample group of at-risk and pathological gamblers seeking treatment. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28(2), 239–252. doi: 10.1007/s10899-011-9258-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granero R., Penelo E., Stinchfield R., Fernandez-Aranda F., Savvidou L. G., Fröberg F., Aymamí N., Gómez-Peña M., Pérez-Serrano M., del Pino-Gutiérrez A., Menchón J. M., Jiménez-Murcia S. (2014). Is pathological gambling moderated by age? Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(2), 475–492. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9369-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granö N., Virtanen M., Vahtera J., Elovainio M., Kivimäki M. (2004). Impulsivity as a predictor of smoking and alcohol consumption. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(8), 1693–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. E., Chamberlain S. R. (2014). Impulsive action and impulsive choice across substance and behavioral addictions: Cause or consequence? Addictive Behaviors, 39(11), 1632–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K. L., Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2007). Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Harris L., Chelminski I., Dalrymple K., Morgan T., Zimmerman M. (2018). Suicide attempts and emotion regulation in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 232, 300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger A. R., Um M., Cyders M. A. (2017). The relationship between the UPPS-P impulsive personality traits and substance use psychotherapy outcomes: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervás G., Jódar R. (2008). The Spanish version of the difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Clinica Y Salud, 19(2), 139–156. Retrieved from http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/clinsa/v19n2/v19n2a01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D. C., Mansley C., Thygesen K. (2006). Risk factors for suicide ideation and attempts among pathological gamblers. American Journal on Addictions, 15(4), 303–310. doi: 10.1080/10550490600754366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia S., Granero R., Tárrega S., Angulo A., Fernández-Aranda F., Arcelus J., Fagundo A. B., Aymamí N., Moragas L., Sauvaget A., Grall-Bronnec M., Gómez-Peña M., Menchón J. M. (2016). Mediational role of age of onset in gambling disorder, a path modeling analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(1), 327–340. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9537-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K., Preacher K. J. (2012). On effect size. Psychological Methods, 17(2), 137–152. doi: 10.1037/a0028086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kräplin A., Bühringer G., Oosterlaan J., van den Brink W., Goschke T., Goudriaan A. E. (2014). Dimensions and disorder specificity of impulsivity in pathological gambling. Addictive Behaviors, 39(11), 1646–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D. R., Miller J. D., Miller D. J., Bornovalova M. A., Lejuez C. W. (2011). Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: A test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 2(2), 151–160. doi: 10.1037/a0019978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccallum F., Blaszczynski A. (2003). Pathological gambling and suicidality: An analysis of severity and lethality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(1), 88–98. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.1.88.22781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam J. F., Yoon G., Dickerson D. L., Kim S. W., Westermeyer J. (2015). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in five groups with different severities of gambling: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(4), 292–298. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas J. F., Contreras-Rodríguez O., Verdejo-Román J., Perandrés-Gómez A., Albein-Urios N., Verdejo-García A., Perales J. C. (2017). Trait and neurobiological underpinnings of negative emotion regulation in gambling disorder. Addiction, 112(6), 1086–1094. doi: 10.1111/add.13751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu A. D., Fang C. M., Rodriguez M., Rosenthal M. Z. (2018). Suicidal behavior and problems with emotion regulation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(1), 52–74. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorolajal J., Haghtalab T., Farhadi M., Darvishi N. (2016). Substance use disorder and risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide death: A meta-analysis. Journal of Public Health, 38(3), e282–e291. doi: 10.1093/pubmed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza M. N. (2013). Neurobiology of gambling behaviors. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(4), 660–667. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P., Hawton K., Mortensen P. B., Webb R. (2014). Combined effects of physical illness and comorbid psychiatric disorder on risk of suicide in a national population study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(6), 430–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cintas L., Daigre C., Braquehais M. D., Palma-Alvarez R. F., Grau-López L., Ros-Cucurull E., Rodríguez-Martos L., Abad A. C., Roncero C. (2018). Factors associated with lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in outpatients with substance use disorders. Psychiatry Research, 262, 440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronzitti S., Soldini E., Smith N., Potenza M. N., Clerici M., Bowden-Jones H. (2017). Current suicidal ideation in treatment-seeking individuals in the United Kingdom with gambling problems. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J., Gross J. J. (2006). When emotion goes wrong: Realizing the promise of affective science. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 227–232. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la fuente J. R., Grant M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvaget A., Jiménez-Murcia S., Fernández-Aranda F., Fagundo A. B., Moragas L., Wolz I., Veciana De Las Heras M., Granero R., Del Pino-Gutiérrez A., Baño M., Real E., Aymamí M. N., Grall-Bronnec M., Menchón J. M. (2015). Unexpected online gambling disorder in late-life: A case report. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 655. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvidou L. G., Fagundo A. B., Fernández-Aranda F., Granero R., Claes L., Mallorquí-Baqué N., Verdejo-García A., Steiger H., Israel M., Moragas L., Del Pino-Gutiérrez A., Aymamí N., Gómez-Peña M., Agüera Z., Tolosa-Sola I., La Verde M., Aguglia E., Menchón J. M., Jiménez-Murcia S. (2017). Is gambling disorder associated with impulsivity traits measured by the UPPS-P and is this association moderated by sex and age? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 72, 106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L. R. N., Grant J. E., Odlaug B. L. (2012). Emotion regulation and impulsivity in young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(5), 651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelef L., Fruchter E., Hassidim A., Zalsman G. (2015). Emotional regulation of mental pain as moderator of suicidal ideation in military settings. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 765–769. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M., Wang P., Soh P., Vaingankar J. A., Chong S. A., Browning C. J., Thomas S. A. (2015). Prevalence and determinants of gambling disorder among older adults: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors, 41, 199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann A. C., Dougherty D. M., Pazzaglia P. J., Pham M., Steinberg J. L., Moeller F. G. (2005). Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(9), 1680–1687. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-García A., Lawrence A. J., Clark L. (2008). Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-García A., Lozano Ó., Moya M., Alcázar M. Á., Pérez-García M. (2010). Psychometric properties of a Spanish version of the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale: Reliability, validity and association with trait and cognitive impulsivity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(1), 70–77. doi: 10.1080/00223890903382369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S. P., Lynam D. R. (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(4), 669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S. P., Lynam D. R., Miller J. D., Reynolds S. K. (2005). Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality, 19(7), 559–574. doi: 10.1002/per.556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. D., Grisham J. R., Erskine A., Cassedy E. (2012). Deficits in emotion regulation associated with pathological gambling. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(2), 223–238. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolz I., Agüera Z., Granero R., Jiménez-Murcia S., Gratz K. L., Menchón J. M., Fernández-Aranda F. (2015). Emotion regulation in disordered eating: Psychometric properties of the difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale among Spanish adults and its interrelations with personality and clinical severity. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 907. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P. W. C., Kwok N. C. F., Tang J. Y. C., Blaszczynski A., Tse S. (2014). Suicidal ideation and familicidal-suicidal ideation among individuals presenting to problem gambling services. Crisis, 35(4), 219–232. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]