Abstract

Background and aims

Sex addiction is characterized by excessive sexual activity on the Internet. We have investigated the contribution of the Big Five personality factors and sex differences to sex addiction.

Methods

A total of 267 participants (186 males and 81 females) were recruited from Internet sites that are used for finding sexual partners. Participants’ mean age was 31 years (SD = 9.8). They filled in the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST), the Big Five Index, and a demographic questionnaire.

Results

Men have shown higher scores of sex addiction than women (Cohen’s d = 0.40), they were more open to experiences (Cohen’s d = 0.42), and they were less neurotic than women (Cohen’s d = 0.67). Personality factors contributed significantly to the variance of sex addiction [F(5, 261) = 6.91, p < .001, R2 = .11]. Openness to experience (β = 0.18) and neuroticism (β = 0.15) had positive correlations with SAST scores, whereas conscientiousness (β = −0.21) had a negative correlation with SAST scores, and personality traits explained 11.7% of the variance. A parallel moderation model of the effect of gender and personality traits on sex addiction explained 19.6% of the variance and it has indicated that conscientiousness had a negative correlation with SAST scores. Greater neuroticism was associated with higher scores of SAST in men but not in women.

Discussion and conclusions

This study confirmed higher scores of sex addiction among males compared to females. Personality factors together with gender contributed to 19.6% of the variance of ratings of sex addiction. Among men, neuroticism was associated with greater propensity for sex addiction.

Keywords: sex addiction, compulsive sexual behavior, Big Five Index, personality, sex differences

Introduction

Sex addiction, otherwise known as compulsive sexual behavior, is characterized by extensive sexual behavior and unsuccessful efforts to control excessive sexual behavior. It is a pathological behavior that has compulsive, cognitive, and emotional consequences (Karila et al., 2014; Weinstein, Zolek, Babkin, Cohen, & Lejoyeux, 2015). Several studies have aimed to explore the etiology of sex addiction and the contribution of background factors, such as personality type and gender to the development of sex addiction (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2014; Lewczuk, Szmyd, Skorko, & Gola, 2017). The majority of the research on sexual addiction is based on samples of males rather than females (Karila et al., 2014).

There is inconsistency regarding the definition of sex addiction. Goodman (1993) defined sexual addiction as a failure to resist sex urges. At least one of the followings is typical of such behavior: regular occupation with sexual activity that is preferred to other activities, restlessness when it is not possible to perform sexual activity and tolerance to this behavior. Mick and Hollander (2006) defined sex addiction as a compulsive and impulsive sexual behavior, whereas Kafka (2010) defined sex addiction as hypersexuality, which is the sexual behavior above average that is characterized by failure to stop the sexual behavior, despite dire social and occupational consequences. In view of the several definitions of sex addiction, one of the challenges is to determine what constitutes sex addiction. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-5) uses the term hypersexuality as a symptom (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), but this term is problematic since most of the patients do not feel that their activity or sexual urges are above average; moreover, the DSM-5 not use the term hypersexuality as mental disorder. Second, the term is misleading since sex addiction is a result of a sexual drive or urge and not of exceptional sexual desire and finally sex addiction can manifest in different ways that do not necessarily conform to this definition (Hall, 2011). According to the ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2018), compulsive sexual behavior disorder is characterized by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses resulting in repetitive sexual behavior. Accordingly, the symptoms of this disorder include repetitive sexual activities that induce significant mental distress and eventually harm individual’s physical and mental health, despite unsuccessful effort to reduce that repetitive sexual impulses and behaviors.

Individuals with sex addiction use a variety of sexual behaviors including excessive use of pornography, chat rooms, and cybersex on the Internet (Rosenberg, Carnes, & O’Connor, 2014; Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015). Sex addiction is a pathological behavior with compulsive, cognitive, and emotional characteristics (Fattore, Melis, Fadda, & Fratta, 2014). The compulsive element includes looking for new sexual partners, high frequency of sexual encounters, compulsive masturbation, regular use of pornography, unprotected sex, low self-efficacy, and use of drugs. The cognitive-emotional component includes obsessive thoughts about sex, guilt feelings, a need to avoid unpleasant thoughts, loneliness, low self-esteem, shame, and secrecy about sexual activity, rationalizations about continuation of sexual activity, preference for anonymous sex, and lack of control over several aspects of life (Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015).

Several theories explain sex addiction. One of them is attachment theory that argues that individuals with anxious or avoidant attachment are afraid of intimacy and use fantasy or sexual addiction as a replacement for intimacy (Zapf, Greiner, & Carroll, 2008). A recent study has shown an association between sex addiction and anxious and avoidant attachment (Weinstein, Katz Eberhardt, Cohen, & Lejoyeux, 2015). The opportunity, attachment, and trauma model (Hall, 2013) expands the attachment model and includes four components – opportunity, attachment, trauma, and a combination of attachment and trauma. In sex addiction, there is a real opportunity for sexual activity or stimuli, such as pornography and sex on the Internet, that can stimulate the urges for sexual enjoyment. Second, early experiences of attachment form the basis for sex addiction. Third, trauma can lead on its own to sex addiction or in combination with insecure attachment (Hall, 2013). Finally, there is the BERSC model that examines the biological, emotional, religious, social, and cultural influences on sex addiction (Hall, 2014).

There are sex differences in sexual behavior and these relate to differences in male and female hormones but also in emotional and psychological aspects of sexual behavior (Fattore et al., 2014). It is argued that, in women, sex addiction is closely associated with early traumatic experiences and also that unfulfilled expectations from a relationship can result in deviant sexual behavior (Fattore et al., 2014). Lewczuk et al. (2017) found a correlation between depression and anxiety and problematic pornography use among females. Women often associate sexual behavior with the need for a connection and relationship (McKeague, 2014) and they would therefore use virtual reality and cybersex in order to relate to sexual partners (Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015). Dhuffar and Griffiths (2014) showed that shame and religious beliefs did not predict hypersexual behavior in women. On the other hand, men try to handle negative emotional states with sexual behavior (Bancroft & Vukadinovic, 2004), and they showed higher rates of craving for pornography and frequenct use of cybersex than women (Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015).

Previous studies have identified five major personality factors: extroversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness (McCrae & John, 1992) and these may show an association with sex addiction. According to Schmitt et al. (2004), individuals who are highly extroverted had sexual activity at an early age, many sexual partners, variety of sexual activity, and dangerous and careless sexual activity compared with introverted individuals. Neuroticism has been associated with liberal views about sex, unsafe sex, a problem in impulse control and negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, and anger. Individuals with low agreeableness and conscientiousness typically enjoy unsafe sex, sexual liberalism, and impulsive risk-taking behavior compared with those with high agreeableness and conscientiousness. Finally, men with low openness tend to develop dangerous sexual behavior, such as infidelity and promiscuous sexual behavior (Schmitt, 2004). Reid and Carpenter (2009) investigated the personality profile of male hypersexual patients (n = 152) compared with the control group using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). Their findings showed that the hypersexual sample had more clinical symptoms, interpersonal impairments, and general mental distress than the normative sample; yet, they have failed to report significant addictive profile for the sex addiction group. Further research by Egan and Parmar (2013) reported that among male individuals from the general population who are low in extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, and high rates in neuroticism have been associated with greater scores on the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST). Moreover, Internet addiction was associated with greater obsessive–compulsive symptoms and more consumption of cyber pornography. Interestedly, a more recent study showed that consumption of cyber pornography and hypersexual behavior were associated with mental distress more than additional factors including personality traits (Grubbs, Volk, Exline, & Pargament, 2015). Rettenberger, Klein, and Briken (2016) have showed in a recent study that both gender and personality traits are marginal predictors of hypersexual behavior; on the other hand, individual responsiveness toward sexual arousal has been found to be stronger predictors of sex addiction. Finally, Bőthe, Tóth-Király, et al. (2018) have found in a recent study with a large sample size that impulsivity and compulsivity had a substantial association with pornography use and a strong positive correlation with hypersexuality in both men and women.

In view of the scarce literature on the relationships between personality and sex addiction, the aim of this study is to examine the association between personality factors and gender and sexual addiction among men and women. We hypothesized that neuroticism would be positively associated with sex addiction (Schmitt et al., 2004), and that conscientiousness and agreeableness would be negatively associated with sex addiction (Schmitt et al., 2004). Finally, we have assumed that there would be gender differences in the association between personality factors and sex addiction (Reid & Carpenter, 2009).

Methods

Participants

There were 267 participants in the study, 186 men and 81 women with mean age of 30 years and 2 months (SD = 9.8) and age range of 18–68, where all of them were of an Israeli nationality. The majority of the participants were single (46.8%), 21.7% were married, 19.1% were in unmarried relationship, 1.5% were separated, and 10.9% were either separated or divorced. The educational profile of the participants included 2.2% with elementary education, 30.7% with high-school education, and 67% with higher academic education or an equal certification study. The occupational profile included 46.4% fully employed, 33.7% with part-time employment, and 19.9% unemployed. Most of the participants lived in the city (81.6%), the rest of the participants lived in cooperative communities or villages. The majority of the participants were Jewish (93.6%), 1.1% Muslims, 1.1% Christians, and 4.1% other (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Men | Women | Significant (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 186 (69.7) | 81 (30.3) | |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 25.23 | 32.34 | <.01a |

| Marital status | <.01b | ||

| Single | 86 (32.2) | 39 (14.6) | |

| In relationship | 20 (7.5) | 31 (11.6) | |

| Married | 48 (18.0) | 10 (3.7) | |

| Separated or divorced | 32 (12.0) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Education | nsb | ||

| Elementary-school education | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.4) | |

| High-school education | 58 (21.7) | 24 (9.0) | |

| Higher education | 123 (46.1) | 56 (21.0) | |

| Occupational status | <.01b | ||

| Unemployment | 32 (12.0) | 21 (7.9) | |

| Part-time job | 50 (18.7) | 40 (15.0) | |

| Full-time job | 104 (39.0) | 20 (7.5) | |

| Place of living | nsb | ||

| City | 153 (57.3) | 65 (24.3) | |

| Cooperative community or village | 33 (12.4) | 16 (6.0) | |

| Religion | |||

| Jewish | 176 (65.9) | 74 (27.7) | nsb |

| Muslims | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Christians | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Others | 6 (2.2) | 5 (1.9) |

Note. SD: standard deviation; Frequencies: percentages within total sample; age: reported in years; education: elementary school is up to 8 years of study, high school refers to as up to 12 years of study, and higher education refers to as obtained an academic degree; ns: non-significant difference.

aSignification of independent t-test. bsignification of Pearson’s χ2 test.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic self-report questionnaire included items regarding age, gender, education, employment status, marital status, type of living, and religion.

Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST)

The SAST (Carnes & O’Hara, 1991) has 25 items that measure sexual addiction. The items on the SAST are dichotomous with an endorsement of an item resulting in an increase by 1 in total score. Score above 6 indicates hypersexual behavior, and a total score of 13 or more on the SAST results in a 95% true positive rate for sexual addiction (i.e., a 5% or less chance of incorrectly identifying a person as a sexual addict; Carnes & O’Hara, 1991). The internal consistency of the SAST in this study was acceptable (Cronbach’s α was .75). The Hebrew version of this questionnaire was validated by Zlot, Goldstein, Cohen, and Weinstein (2018) where it had a Cronbach’s α of .80.

Big Five Index (BFI)

The BFI (McCrae & John, 1992) consists of 44 items that measure personality traits based on the Big Five model (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991). Items are self-rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” Each item represents the core traits that define each of Big Five domains: extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. In this study, Cronbach’s α ranged between .69 and .82.

Procedure

The questionnaires were advertised online in social network forums that were dedicated for dating and finding partners for sex. Participants answered questionnaires online through the Internet. Participants were informed that the study investigates sex addiction and that the questionnaires will remain anonymous for a research purpose.

Statistical and data analysis

The analysis of the results was performed on a Statistical Package for Social Science windows v.21 (SPSS; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). In order to explore differences in demographic factors between men and women, data referring to marital status, education, occupational status, place of living, and religion were analyzed using a Pearson’s χ2 test, and age and sex addiction ratings and personality traits between men and women were determined using independent t-tests; effect size was calculated using a Cohen’s d. Simple correlation test between study variables was calculated using a Pearson’s correlation test. To estimate the contribution of personality and gender to scores of sex addiction, initial separate regression models with gender, and personality traits as predictors of sex addiction were preformed and a further parallel moderation model analysis of gender and personality traits and sex addiction was conducted using PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2015).

Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB, Helsinki committee) of Ariel University. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Results

Sample characteristics

Scores on the sex addiction questionnaires indicated that 120 participants (95 men and 25 women) were classified as sex addiction and a 147 as non-sex-addicted, following criteria defined by Carnes and O’Hara (1991) (SAST score > 6). Ratings of personality factors were above mean (>3) except neuroticism, which was lower (mean = 2.58). The distribution of ratings on the questionnaire was homogenous (SD = 0.57). A comparison of sex addiction between men and women showed that men had higher ratings (mean = 6.61, SD = 3.75) than women (mean = 4.61, SD = 3.52) [t(1,265) = 4.07, p < .001)], with a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.40). In addition, a comparison of personality factors between men and women showed that men were more open to experiences (mean = 3.68, SD = 0.51) than women (mean = 3.44, SD = 0.63) [t(1,265) = 2.95, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.42], and they were less neurotic (mean = 2.44, SD = 0.67) than women (mean = 2.91, SD = 0.74) [t(1,265) = 5.06, p < .01, Cohen’s d = 0.67].

The association between personality traits and sex addiction

An initial Pearson’s correlation test indicated a negative correlation between agreeableness, and conscientiousness with sex addiction, and a positive correlation between neuroticism and sex addiction (Table 2). A further regression analysis indicated that personality factors contributed significantly to the variance of sex addiction [F(5, 261) = 6.91, p < .001, R2 = .11]. Conscientiousness negatively contributed to sexual addiction scores. On the other hand, openness to experience and neuroticism positively contributed to scores of sex addiction. Agreeableness did not make a significant contribution to ratings of sex addiction nor did extraversion (Table 3). The model indicated no multicollinearity as a variance inflation factor that ranged between 1.27 and 1.51, and a tolerance index that ranged between 0.65 and 0.86.

Table 2.

Simple correlations between personality traits and sex addiction

| Factor | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex addiction | 5.91 (3.96) | ||||||

| 2. Conscientiousness | 3.78 (0.60) | −0.28** | |||||

| 3. Openness | 3.61 (0.57) | 0.10 | 0.06 | ||||

| 4. Neuroticism | 2.58 (0.73) | 0.22** | −0.43** | −0.21 | |||

| 5. Agreeableness | 3.84 (0.60) | −0.18** | 0.45** | 0.10 | −0.41** | ||

| 6. Extraversion | 3.48 (0.61) | −0.62 | 0.35** | 0.32** | −0.22 | 0.21** |

Note. Simple correlations were calculated using Pearson’s analysis. M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis of personality factors contribution to sex addiction scores

| Factor | B | SE B | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness | −1.45 | 0.45 | −0.23** | −3.24 |

| Openness | 1.23 | 0.42 | 0.18** | 2.96 |

| Neuroticism | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.13* | 1.92 |

| Agreeableness | −0.28 | 0.42 | −0.05 | −0.67 |

| Extraversion | −0.14 | 0.40 | −0.02 | −0.35 |

| R2 | .131 | |||

| F | 7.89 |

Note. SE B: standard error of B; β: standardized beta coefficient.

**p < .01. *p < .056.

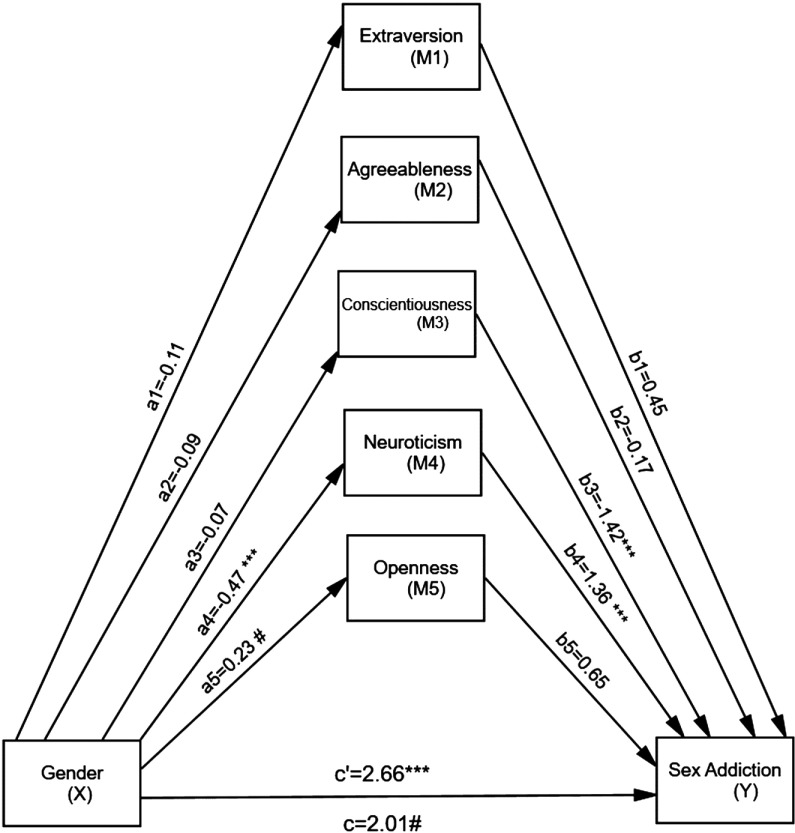

The contribution of gender and personality traits to sex addiction

In order to estimate gender differences and the contribution of personality factors to sex addiction scores, a parallel moderation analysis was performed and the model explain 19.6% of the variance of sex addiction [F(6, 260) = 10.6, p < .0001]. The results indicated that men were less neurotic (a4 = −0.47, p < .001) and more open to experiences (a5 = 0.23, p < .001) than women. In addition, lower conscientiousness (b3 = −1.42, p < .001) and greater neuroticism (b4 = 1.36, p < .001) were related to greater sexual addiction. A 95% bias-corrected confidence interval based on 10,000 bootstrap samples indicated that the indirect effect through neuroticisms (a1b1 = 0.64), holding all other factors constant, was entirely above zero (0.25–1.15). On the contrary, the indirect effects through the rest of Big Five domains, such as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience, were not different from zero (−0.05 to 0.23, −0.07 to 0.15, −0.10 to 0.37, and −0.42 to 0.05, respectively). Moreover, men reported greater scores of sex addiction even when considering gender’s indirect effect through all five dimensions of personality (c’ = 2.66, p < .001; Figure 1). Altogether, this indirect effect indicated that greater neuroticism is associated with greater sex addiction in men rather than in women.

Figure 1.

Model of the moderation effect of personality traits in the relationship between gender and sex addiction. Note. All presented effects are unstandardized; an is effect of gender on personality traits, women are coded as 0 and men as 1; bn is the effect of personality traits on sex addiction; c is direct effect of gender on sex addiction; c’ is total effect of gender on sex addiction. ***p < .0001. #p < .001

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between personality and sexual addiction in men compared to women. We have corroborated previous evidence for higher levels of sex addiction in men (Eisenman, Dantzker, & Ellis, 2004; Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015). Second, we have found that conscientiousness contributed negatively to ratings of sex addiction in men and women. This finding is in agreement with the results reported by Schmitt et al. (2004). We have also found that conscientiousness negatively contributed to ratings of sex addiction independently of other factors, such as agreeableness, unlike Schmitt et al. (2004) who found that agreeableness was negatively associated with sex addiction, and unlike Egan and Parmar (2013) who found that among male individuals, low in extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness, and high rates in neuroticism were associated with greater scores on the SAST. Yet, the study conducted by Egan and Parmar (2013) used a sample of healthy individuals based on the general population.

There are different explanations for the association between low conscientiousness and sex addiction. Wordecha et al. (2018) reported that binge masturbation is related to decreased mood, increased stress, and anxiety. Low conscientiousness is associated with mental distress and psychopathology (Reid & Carpenter, 2009). It is plausible that the association reported in this study is a result of adverse childhood experiences and attachment difficulties or alternatively that the high sensation seeking and excitement associated with sex addiction reduced the level of conscientiousness (Grubbs, Perry, Wilt, & Reid, 2018). Longitudinal studies may help elucidate these issues.

The effect of neuroticism on sex addiction was greater in men. This finding is in conformity with previous studies showing that neuroticism is associated with impulsive and risk-taking behavior related to sex (Hoyle, Fejfar, & Miller, 2000; Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000). Other factors such as extroversion and agreeableness were not associated with sex addiction in this study, although the literature found that high extraversion and low agreeableness are closely associated with sex addiction (Karila et al., 2014).

There are very few studies on personality and sex addiction. Reid and Carpenter (2009) investigated the differences between male hypersexual patients (n = 152) and normative group responses to MMPI-2. Their findings showed that nearly all validity and clinical scales were higher for the hypersexual sample than the normative sample. However, these elevations generally did not fall within the clinical range, and approximately one third of the tested population had normal profiles. MMPI-2 clinical scales with the most frequent elevations for the hypersexual population included phobias, obsessions, compulsions, or excessive anxiety; psychopathic deviate characterized by general maladjustment, unwillingness to identify social convention and norms, impulse–control problems; and depression. Furthermore, there was no overall support for addictive tendencies or classifying the patients as obsessive or compulsive, but that their cluster analysis provided evidence to support the idea that hypersexual patients are a diverse group of individuals. These findings are similar to Levine’s (2010) retrospective multiple-case analysis that also calls into question the level of psychopathology among those with problematic sexual behaviors. Overall, the results of this study may have strong implication regarding the theoretical understanding of behavioral addictions in general and particularly sex addiction. The results of this study support the view of Griffiths (2017) who suggested that personality factors could not explain exclusively addiction; yet, it is a result of biopsychosocial factors that are influenced from internal and external determinants. This conclusion is supported by recent studies that showed that other factors such as mental distress (Grubbs et al., 2015) and sexual arousal are stronger predictors than personality of hypersexual behavior (Rettenberger et al., 2016), although further research is needed to clarify this issue.

Limitations

The main limitation in this study is the reliance of recruitment through dating and social network websites that do not enable a direct verification of the validity or reliability or the state of mind of the responses by the participants. A second limitation is the lower response rate among women that was also seen in previous studies (Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015). Moreover, this study based on cross-sectional, self-report sample and therefore it might be biased due to social desirability. Finally, personality factors only explained a small proportion (11%) of the variance in ratings of sex addiction and together with gender they explain 19.6% of sex addiction. Other factors are more important in explaining the variance in sex addiction. It is possible that craving for sex and compulsion to enter websites for cybersex are much more powerful in prediction of sex addiction (Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015).

In conclusion, this study confirmed previous evidence for higher scores of sex addiction among males compared to females (Weinstein, Zolek, et al., 2015). It also showed that personality factors such as (lack of) conscientiousness and openness contributed to sex addiction. Among men, neuroticism was associated with greater propensity for sex addiction. Further studies can examine personality and sex interactions among other populations, such as couples (most of our sample were not in a relationship), religious people, and homosexual populations (Bőthe, Bartók, et al., 2018).

Acknowledgements

The study was presented in the 4th ICBA meeting in Haifa Israel in February 2017.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: The study was carried out as part of an academic course in behavioral addiction at the Ariel University, Ariel, Israel.

Authors’ contribution

All individuals included as authors of the paper have contributed substantially to the scientific process leading up to the writing of the paper. The authors have contributed to the conception and design of the project, performance of the experiments, analysis and interpretation of the results, and preparation of the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no interests or activities that might be seen as influencing the research (e.g., financial interests in a test or procedure and funding by pharmaceutical companies for research). They report no conflict of interest regarding this study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J., Vukadinovic Z. (2004). Sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, or what? Toward a theoretical model. Journal of Sex Research, 41(3), 225–234. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Bartók R., Tóth-Király I., Reid R. C., Griffiths M. D., Demetrovics Z., Orosz G. (2018). Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. Advance online publication. 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1201-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Potenza M. N., Griffiths M. D., Orosz G., Demetrovics Z. (2018). Revisiting the role of impulsivity and compulsivity in problematic sexual behaviors. The Journal of Sex Research. Advance online publication. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1480744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes P., O’Hara S. (1991). Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST). Tennessee Nurse, 54(3), 29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhuffar M., Griffiths M. (2014). Understanding the role of shame and its consequences in female hypersexual behaviours: A pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(4), 231–237. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.4.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan V., Parmar R. (2013). Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(5), 394–409. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.710182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman R., Dantzker M. L., Ellis L. (2004). Self ratings of dependency/addiction regarding drugs, sex, love, and food: Male and female college students. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 11(3), 115–127. doi: 10.1080/10720160490521219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L., Melis M., Fadda P., Fratta W. (2014). Sex differences in addictive disorders. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35(3), 272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. (1993). Diagnosis and treatment of sexual addiction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 19(3), 225–251. doi: 10.1080/00926239308404908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D. (2017). The myth of “addictive personality”. Global Journal of Addiction & Rehabilitation Medicine (GJARM), 3(2), 555610. doi: 10.19080/GJARM.2017.03.555610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs J. B., Perry S. L., Wilt J. A., Reid R. C. (2018). Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: An integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior. Advance online publication. 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1248-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs J. B., Volk F., Exline J. J., Pargament K. I. (2015). Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(1), 83–106. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2013.842192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. (2011). A biopsychosocial view of sex addiction. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26(3), 217–228. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2011.628310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. (2013). A new classification model for sex addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(4), 279–291. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2013.807484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. (2014). Sex addiction – An extraordinarily contentious problem. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(1), 68–75. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2013.861898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle R. H., Fejfar M. C., Miller J. D. (2000). Personality and sexual risk taking: A quantitative review. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 1203–1231. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John O. P., Donahue E. M., Kentle R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archive of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L., Wéry A., Weinstein A., Cottencin O., Petit A., Reynaud M., Billieux J. (2014). Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: Different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4012–4020. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. B. (2010). What is sexual addiction? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 36(3), 261–275. doi: 10.1080/00926231003719681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewczuk K., Szmyd J., Skorko M., Gola M. (2017). Treatment seeking for problematic pornography use among women. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 445–456. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R. R., John O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five‐factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60, 175–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeague E. L. (2014). Differentiating the female sex addict: A literature review focused on themes of gender difference used to inform recommendations for treating women with sex addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21(3), 203–224. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2014.931266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mick T. M., Hollander E. (2006). Impulsive-compulsive sexual behavior. CNS Spectrum, 11(12), 944–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid R. C., Carpenter B. N. (2009). Exploring relationships of psychopathology in hypersexual patients using the MMPI-2. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 35(4), 294–310. doi: 10.1080/00926230902851298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettenberger M., Klein V., Briken P. (2016). The relationship between hypersexual behavior, sexual excitation, sexual inhibition, and personality traits. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 219–233. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0399-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg K. P., Carnes P., O’Connor S. (2014). Evaluation and treatment of sex addiction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(2), 77–91. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.701268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D. P. (2004). The Big Five related to risky sexual behaviour across 10 world regions: Differential personality associations of sexual promiscuity and relationship infidelity. European Journal of Personality, 18(4), 301–319. doi: 10.1002/per.520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D. P., Alcalay L., Allensworth M., Allik J., Ault L., Austers I., ZupanÈiÈ A. (2004). Patterns and universals of adult romantic attachment across 62 cultural regions: Are models of self and of other pancultural constructs? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(4), 367–402. doi: 10.1177/0022022104266105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein A., Katz L., Eberhardt H., Lejoyeux M. (2015). Sexual compulsion – Relationship with sex, attachment and sexual orientation. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(1), 22–26. doi: 10.1556/JBA.4.2015.1.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein A. M., Zolek R., Babkin A., Cohen K., Lejoyeux M. (2015). Factors predicting cybersex use and difficulties in forming intimate relationships among male and female users of cybersex. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordecha M., Wilk M., Kowalewska E., Skorko M., Łapiński A., Gola M. (2018). “Pornographic binges” as a key characteristic of males seeking treatment for compulsive sexual behaviors: Qualitative and quantitative 10-week-long diary assessment. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 433–444. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). The ICD-11 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Retrieved from http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. Accessed on: September 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf J. L., Greiner J., Carroll J. (2008). Attachment styles and male sex addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 15(2), 158–175. doi: 10.1080/10720160802035832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zlot Y., Goldstein M., Cohen K., Weinstein A. (2018). Online dating is associated with sex addiction and social anxiety. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. Advance online publication. 1–6. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M., Kuhlman D. M. (2000). Personality and risk-taking: Common bisocial factors. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 999–1029. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]