Among idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common and lethal, and typically presents in elderly subjects with a history of cigarette smoking. IPF is usually progressive and the median survival from the time of diagnosis is only ∼3 years (1). Two small-molecule therapies are now approved to treat patients with IPF: nintedanib, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and pirfenidone, which has antifibrotic activities on fibroblasts. Both of these therapies slow (but do not prevent) lung function decline, but neither therapy reduces mortality rates in patients with IPF (2).

Obstacles to the development of more effective therapeutics for IPF include the lack of an animal model that accurately recapitulates IPF for drug target identification, and knowledge gaps regarding the key molecular pathways involved in fibrosis initiation and progression. The gold standard animal model for IPF is the murine bleomycin model, but this model has a self-limited fibrotic phase (in contrast to the progressive nature of human IPF), and lacks fibroblastic foci, a hallmark of the human disease (3). The prevailing hypothesis is that IPF results from repetitive injury to the alveolar epithelium, followed by an aberrant wound-healing response with excessive production of profibrotic growth factors, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, hyperproliferation of fibroblasts with a profibrotic phenotype, excessive production of extracellular matrix with progressive fibrosis, destruction of the alveolar architecture, and impaired gas exchange (4, 5). Adaptive immunity and a skewed T-helper cell type 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytokine balance have been implicated in IPF, as Th1 cytokines (e.g, IFN-γ and IL-12) attenuate fibrosis, whereas Th2 cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) promote fibrosis in animal models (6).

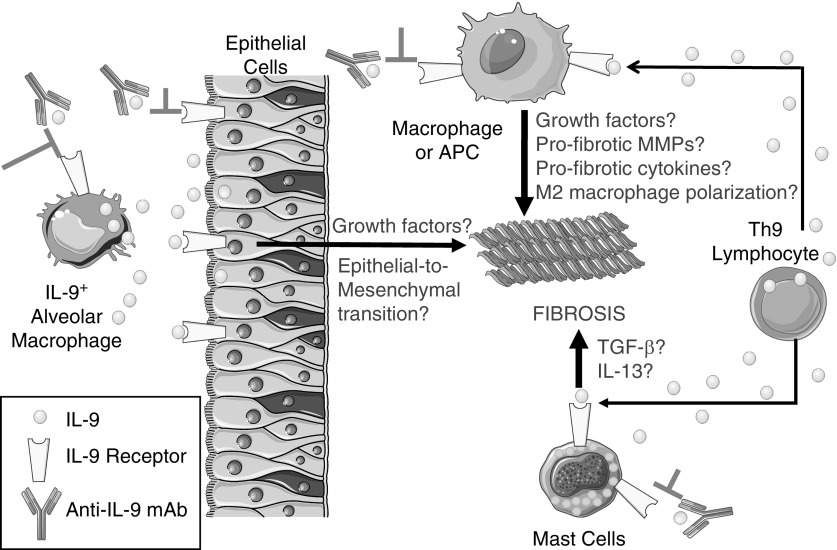

IL-9 is another Th2 cytokine that has been implicated in fibrotic responses. IL-9 is produced primarily by helper T lymphocytes (Th9 cells) and signals via a receptor expressed on mast cells, macrophages, and T and B lymphocytes. IL-9 is a growth factor for activated T cells and mast cells; it stimulates immunoglobulin production by B lymphocytes, promotes mucus metaplasia by inducing IL-13 release, and induces Th2 immune responses (7, 8). However, the activities of IL-9 in the pathogenesis of IPF are incompletely understood. In a study presented in this issue of the Journal, Sugimoto and colleagues (pp. 232–243) addressed gaps in this field by testing the efficacy of a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to IL-9 in a murine model of pulmonary fibrosis (9). A single dose of silica was delivered by the intranasal route to mice, which induced an acute inflammatory response in the lung that resolved within 2–4 weeks. The silica treatment induced sustained increases in lung levels of IL-9 and growth factors that have been implicated in IPF (transforming growth factor-β and platelet-derived growth factor). The silica challenge also induced robust pulmonary fibrosis that persisted for 24 weeks, and was associated with increased accumulation of myofibroblasts. To investigate the contributions of IL-9 to silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis, the authors delivered three doses of an anti–IL-9 mAb to the mice beginning at week 3 (when the acute inflammatory response was resolving) and at 2-week intervals thereafter. The mAb limited the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, and reduced the lung levels of some growth factors and Th1 and Th2 cytokines. In human IPF lungs there was increased staining for IL-9 in airway CD4+ T cells and type I (but not type II) airway and alveolar epithelial cells. Staining for the IL-9 receptor was detected in type I epithelial cells. Surprisingly, alveolar macrophages expressed IL-9, raising the possibility that autocrine activation of macrophages (and type I epithelial cells) coupled with paracrine activation of lung epithelial cells by IL-9 released by Th9 cells and macrophages synergistically promote pulmonary fibrosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms by which IL-9 promotes pulmonary fibrosis. In the lungs of humans with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and the lungs of mice with silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis, IL-9 is expressed by alveolar macrophages, CD4+ lymphocytes (T-helper type [Th] 9 cells), and type I airway and alveolar epithelial cells. The IL-9 receptor (IL-9R) is expressed by type I epithelial cells, lymphocytes, mast cells, macrophages, and antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The mechanisms by which IL-9 promotes (and a monoclonal antibody [mAb] to IL-9 inhibits) fibrosis in mice is not clear. Based on the known activities of IL-9 in vitro and in other animal models of disease, we hypothesize that 1) binding of IL-9 to the IL-9R on type I epithelial cells may promote pulmonary fibrosis by inducing the release of profibrotic growth factors and/or stimulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; 2) binding of IL-9 to the IL-9R on macrophages or other APCs may promote pulmonary fibrosis by stimulating the release of profibrotic growth factors, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), or cytokines, and/or inducing M2 macrophage polarization; and 3) binding of IL-9 to IL-9R on mast cells may promote pulmonary fibrosis by stimulating the release of profibrotic growth factors and cytokines such as IL-13. These events may act in concert to induce excessive deposition of extracellular matrix by myofibroblasts in the lungs, with loss of the normal alveolar architecture, and impaired gas exchange. TGF-β = transforming growth factor-β.

A strength of this study is that a therapeutic dosing strategy was tested in an animal model that led to robust and sustained pulmonary fibrosis. Detailed time-course responses for a broad array of mediators were conducted, and the anti–IL-9 mAb substantially reduced pulmonary fibrosis. However, there are also several limitations. The authors studied only male mice, and fibroblastic foci do not develop in the silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis model in mice. Additionally, the authors did not elucidate the mechanisms by which IL-9 promotes fibrotic responses to injury. IL-9 may exert fibrogenic activities on 1) epithelial cells, including those undergoing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and their release of growth factors; 2) macrophages, including their release of profibrotic growth factors, cytokines, or matrix metalloproteinases, or induction of M2 macrophage polarization, which has been linked to pulmonary fibroproliferative responses (5, 10); and 3) mast cells and antigen-presenting cells, inducing their release of growth factors and profibrotic cytokines (7) (Figure 1). The authors also did not initiate anti–IL-9 mAb therapy later than 3 weeks in the model to determine whether delayed initiation of therapy limits the progression of or reverses more chronic fibrotic lung disease.

The results of Sugimoto and colleagues conflict with those of prior studies of IL-9 in silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. In a previous study, transgenic mice that constitutively overexpress IL-9 at high levels in T cells showed a reduced Th2 immune response, increased influx of B cells into the lungs, and decreased pulmonary fibrosis when challenged with silica (11). These findings were recapitulated when silica-treated wild-type mice received IL-9 by the intraperitoneal route (11), indicating that IL-9 has antifibrotic activities in these models that may be mediated in part by IL-9–mediated suppression of Th2 immune responses. It remains unclear why these results differ from those of Sugimoto and colleagues.

The efficacy of anti–IL-9 mAbs has previously been evaluated in fibrotic diseases. Antibody-mediated IL-9 blockade reduced the expression of Th1 and Th2 cytokines, and reduced carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic fibrosis in mice (12). Although a study of transgenic mice overexpressing IL-9 in airway club cells reported that these mice spontaneously develop features of asthma, including airway fibrosis (13), an anti–IL-9 mAb was well tolerated but lacked efficacy in phase II clinical trials in patients with poorly controlled asthma (14). If the results of Sugimoto and colleagues are validated in future studies, the efficacy of anti–IL-9 mAbs could be evaluated in clinical trials of patients with IPF and/or silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis (silicosis). The results of Sugimoto and colleagues suggest that intervention in patients with silicosis or IPF with early-stage disease identified by chest computed tomography scans (15) might benefit from this therapy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Public Health Service, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant AI111475-01; Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute grant CIA123046; and Department of Defense (Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs) grant PR152060.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Hutchinson J, Fogarty A, Hubbard R, McKeever T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:795–806. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00185114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canestaro WJ, Forrester SH, Raghu G, Ho L, Devine BE. Drug treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Chest. 2016;149:756–766. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron RM, Choi AJ, Owen CA, Choi AM. Genetically manipulated mouse models of lung disease: potential and pitfalls. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L485–L497. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00085.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. New cellular and molecular mechanisms of lung injury and fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2012;380:680–688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig VJ, Zhang L, Hagood JS, Owen CA. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53:585–600. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0020TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolahian S, Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O, Hartl D. Immune mechanisms in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55:309–322. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0121TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noelle RJ, Nowak EC. Cellular sources and immune functions of interleukin-9. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nri2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittaker L, Niu N, Temann UA, Stoddard A, Flavell RA, Ray A, et al. Interleukin-13 mediates a fundamental pathway for airway epithelial mucus induced by CD4 T cells and interleukin-9. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:593–602. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugimoto N, Suzukawa M, Nagase H, Koizumi Y, Ro S, Kobayashi K, et al. IL-9 blockade suppresses silica-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;60:232–243. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0287OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lech M, Anders HJ. Macrophages and fibrosis: how resident and infiltrating mononuclear phagocytes orchestrate all phases of tissue injury and repair. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arras M, Huaux F, Vink A, Delos M, Coutelier JP, Many MC, et al. Interleukin-9 reduces lung fibrosis and type 2 immune polarization induced by silica particles in a murine model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:368–375. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.4.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin SY, Lu DH, Guo XY, Luo W, Hu BL, Huang XL, et al. A deleterious role for Th9/IL-9 in hepatic fibrogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18694. doi: 10.1038/srep18694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temann UA, Geba GP, Rankin JA, Flavell RA. Expression of interleukin 9 in the lungs of transgenic mice causes airway inflammation, mast cell hyperplasia, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1307–1320. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh CK, Leigh R, McLaurin KK, Kim K, Hultquist M, Molfino NAA. A randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the effect of an anti-interleukin-9 monoclonal antibody in adults with uncontrolled asthma. Respir Res. 2013;14:93. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washko GR, Lynch DA, Matsuoka S, Ross JC, Umeoka S, Diaz A, et al. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.