Abstract

Rationale: Endometriosis is a highly prevalent gynecological disease in women of reproductive age that markedly reduces life quality and fertility. Unfortunately, there is no cure for this disease, which highlights that more efforts are needed to investigate the underlying mechanism for designing novel therapeutic regimens. This study aims to investigate druggable membrane receptors distinctively expressed in endometriotic cells.

Methods: Bioinformatic analysis of public databases was employed to identify potential druggable candidates. Normal endometrial tissues and ectopic endometriotic lesions were obtained for the determination of target genes. Primary endometrial and endometriotic stromal cells as well as two different mouse models of endometriosis were used to characterize molecular mechanisms and therapeutic outcomes of endometriosis, respectively.

Results: Anthrax toxin receptor 2 (ANTXR2) mRNA and protein are upregulated in the endometriotic specimens. Elevation of ANTXR2 promotes endometriotic cell adhesion, proliferation, and angiogenesis. Furthermore, hypoxia is the driving force for ANTXR2 upregulation via altering histone modification of ANTXR2 promoter by reducing the repressive mark, histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) trimethylation, and increasing the active mark, H3K4 trimethylation. Activation of ANTXR2 signaling leads to increased Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity, which contributes to numerous pathological processes of endometriosis. Pharmacological blocking of ANTXR2 signaling not only prevents endometriotic lesion development but also causes the regression of established lesion.

Conclusion: Taken together, we have identified a novel target that contributes to the disease pathogenesis of endometriosis and provided a potential therapeutic regimen to treat it.

Keywords: endometriosis, hypoxia, EZH2, ANTXR2, cell adhesion

Introduction

Endometriosis is one of the most common gynecological diseases; it is characterized by the presence of endometrial cells outside the uterine cavity and occurs in 8 to 15% of women in the reproductive age 1. Typical symptoms of endometriosis include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pain of pelvis and infertility, which seriously decrease the quality of life and increase financial burden of affected individuals. Moreover, endometriosis is also a risk factor for ovarian cancer 2. Several theories have been proposed to explain the etiology of endometriosis, of which the most accepted one is the retrograde menstruation theory proposed by Sampson 3. According to the Sampson's theory, retrograded endometrial tissues have to overcome several obstacles, such as attaching to peritoneal cavity, escaping immune clearance, surviving in the hostile microenvironment, and propagating in the peritoneal cavity 4, 5. Since adhesion is the first, and maybe the most critical, step for retrograded endometrial tissues to implant in the peritoneal cavity, characterization of its underlying mechanism may provide a valuable information for developing better therapeutic strategies to prevent endometriosis formation and progression.

Previous study has shown that endometrial stromal cell is the major cell type responsible for the attachment to mesothelium by using a transplantation model of human menstrual endometrium in nude mice 6. Furthermore, endometriotic stromal cell has also been reported to have better adhesive ability than normal endometrial stromal cell 7, 8. It has been shown that CD44, a cell surface glycoprotein, is important for the development of endometriosis 9; however, about 30-50% endometriotic lesions still developed in mice lacking CD44 9, suggesting that other uncharacterized molecules are critical for the adhesion and development of endometriotic lesions.

Anthrax toxin receptor 2 (ANTXR2), also called capillary morphogenesis gene-2, is originally identified as the second most upregulated gene upon the formation of capillaries in 3D matrices 10. Later on, ANTXR2 was also identified as the second membrane receptor responsible for allowing the entry of anthrax toxin, a major virulence factor of Bacillus anthracis, into host cells 11. Since then, most studies focused on studying the role of ANTXR2 in pathogenesis of anthrax infection. Unexpectedly, it was found that Antxr2 knockout female mouse failed to deliver due to uterine dysfunction, suggesting that ANTXR2 plays an indispensable role in female reproduction 12. Furthermore, ANTXR2 is also expressed in the uterine endometrial stromal cells 12, and both collagen type IV and laminin are reported as the endogenous ligands for ANTXR2 10. These findings suggest that ANTXR2 may be involved in the adhesive process of endometrial cells and aberrant expression of ANTXR2 might contribute to the pathological process of endometriosis, which has never been examined before.

Herein, we demonstrate that ANTXR2 level is increased in endometriotic cells and hypoxic stress is the driving force for aberrant expression of ANTXR2 in endometriosis. Furthermore, higher ANTXR2 level contributes to a greater adhesive ability of endometriotic stromal cells. More importantly, we show, for the first time, that ANTXR2 activates Yes Associated Protein 1 (YAP1) transcription activity to promote cell proliferation and angiogenesis, while blocking ANTXR2 signaling prevents mouse endometriotic lesion formation. Taken together, our current findings provide a solid evidence to demonstrate that disruptting aberrant cellular adhesive ability may represent an alternative approach to treat endometriosis.

Methods

Clinical samples

The paired eutopic and ectopic tissues were obtained from patients with endometriosis at the time of laparoscopy or laparotomy at the Department of Obstetrics/Gynecology in the National Chung Kung University Hospital. Detailed sample information was listed in Table S1. All tissues were incubated in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium Nutrient Mixture F-12 HAM (DMEM/F12) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) medium and kept on ice until stromal cell isolation. Human Ethics Committee approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at the National Cheng Kung University Medical Center, and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Isolation of primary stromal cells and treatments

In brief, tissues were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Then, tissues were digested with type IV collagenase (2 mg/mL) and DNase I (100 μg/mL) in PBS and shacked with 100 rpm for 60 min at 37 °C. Stromal cells were separated from epithelium cells by filtration with a 70 μm pore size and then 40 μm pore size nylon mesh. Filtered cells were allowed to attach for 30 min in a T-75 flask and then blood cells, tissue debris and epithelial cells were washed away with PBS. Stromal cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% FBS in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The purity of stromal cells was verified by immunofluorescence staining using vimentin (positive marker) and keratin (epithelial cell marker for negative control) antibodies (Figure S1). When subcultured cells reached 70% confluence, the culture medium was changed to a serum-free medium for 24 h. Following starvation, cells were incubated in a fresh medium with 10% FBS and treated with true hypoxia (1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2) for 24 h.

RNA isolation and quantitative-RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions (TRIsure; Bioline USA Inc., Taunton, MA, USA) and concentrations of RNA were determined by an equipment of NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). Reverse transcription was performed at 42 °C for 90 min followed by 95 °C for 10 min. Real-time qPCR was performed on the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) with SYBR Green (Applied Biosystem, 4309155). Primer sequences were listed in Table S2.

Western blot analysis

Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry assay. Equal amount of protein (30 μg/well) was loaded into sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (PerkinElmerTM Life Sciences, Inc., NEF1002, Boston, MA, USA) with Hoefer TE 70 semi-dry transfer unit at an electronic current equal to 0.8 mA/cm2 of gel surface for 2 h. Nonspecific binding was blocked by 5% non-fat milk/PBST for 1 h. The membrane was incubated in the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS 3 times, the membrane was incubated in the secondary antibody for 1 h. Then, the membrane was washed with PBS 12 times. Immunodetection was performed using ECL (PerkinElmerTM Life Sciences, Inc., NEL104/105, Boston, MA, USA). Antibodies used in this study were listed in Table S3

Immunohistochemistry staining and Immunocytochemistry staining

Paraffin-embedded samples were first dewaxed by xylene followed by immersing in 100% ethanol for three times (5 minutes/time). Later, slides were sequentially immersed in 95%, 80%, and 70% ethanol and finally washed by double distilled water. Then, de-waxed samples were subjected to antigen retrieval by immersing in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) followed by a treatment with 3% H2O2 for 5 min. Next, samples were hybridized with antibody in a humidity chamber at 4 °C overnight. After washing for 1 h, color was developed by an AEC substrate buffer (Bio SB, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA) followed by hematoxylin staining (Bio SB, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Finally, samples were mounted with gelatin.

Following treatments, cells were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS washing buffer for 30 min, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then stained with anti-YAP1 antibody (Cell Signaling #14074, 1:100, Danvers, MA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. After washing, cells were treated with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) for 1 h and counterstained with DAPI for nuclei.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The binding between protein and DNA was cross-linked by incubating for 10 min with a final concentration of 1% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, F-1268, St. Louis, MO, USA). Then, cells were incubated with a final concentration of 125 mM glycine for 10 min. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS. These cells were scraped off in 500 μL ice-cold PBS (containing proteinase inhibitors) and centrifuged for 5 min at 600 rcf at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μL cell lysis buffer (containing proteinase inhibitors) and incubated for 15 min on ice. After centrifuging at 2000 rcf for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded and 250 μL nuclear lysis buffer (containing proteinase inhibitors) was added. The chromatin was fragmented to 100-500 base pairs by S220 Focused-ultrasonicators (Covaris Inc, Woburn, Massachusetts, USA). The sonicated samples were diluted with a ChIP dilution buffer. Two percent of diluted lysates was kept for DNA input control. The remaining lysates were incubated with antibodies at 4 °C overnight with rotation. The immune-complexes were washed with low salt, high salt, LiCl and TE buffer and were eluted by an elution buffer containing proteinase K at 62 °C for 2 h. The DNA was purified through phenol/chloroform washing, precipitated in the presence of glycogen (Roche, 10901393001, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and dissolved in ddH2O. The DNA was further analyzed by StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) with SYBR Green (Applied Biosystem, 4309155).

Cell-electrode impedance attachment assay

The cell attachment was real-time monitored using an electrical impedance assay with xCELLigence RTCA SP device (ACEA Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) in a 37 °C and 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were pretreated with siRNA against ANTXR2 for 48 h and then suspended for cell counting. At the same time, 50 μL FBS-free medium was added to each well to equilibrate at a 37 °C incubator and to record the baseline impedance. After then, 10,000 cells in 150 μL serum-free medium were added in a 96-well electronic microtiter plate (E-Plate® 96, ACEA Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Impedance was measured every 5 min for first 3 h, and every 1 h for another 21 h. The impedance of electron flow caused by adherent cells was reported as cell index (CI) at the 3rd h. The values were expressed as the cell index ± SEM, and each experiment was repeated three times using different batches of cells.

Bioinformatics analysis

To identify novel therapeutic targets, upregulation gene lists (P<0.05, fold change ≥ 1.5) from two public datasets (GSE7305 and GSE5108) containing normal and endometriotic specimens were used to cross-reference gene list with a membrane receptor annotation downloaded from Gene Ontology. Heatmap of epigenetic regulator was generated from GSE7305 (genes with P<0.05 and fold change ≥ 1.5). Genome-wide correlation analysis was performed using publicly available gene expression dataset (GSE51981) after data transformation. Genes correlated with ANTXR2 levels (P<0.05, Pearson's correlation) were further sorted by Gene Ontology classification. YAP1-ChIP-seq from the dataset (GSE55186) was used to investigate direct downstream target gene of YAP1. Finally, ANTXR2 positively- correlated genes and YAP1-binding genes were cross-referenced to identify potential downstream target genes of ANTXR2 which were mediated by YAP1. All the public datasets used in this study were listed in Table S4.

Animal experiment

Eight- to ten-week-old female C57BL/6NCrj mice were purchased from the Animal Center at the College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University. To set up the injection mouse model of endometriosis, estrogen capsule was imbedded at the mouse back for two days. After estrogen stimulation, two sides of uteri were removed from the donor mice and endometria were collected and fragmented into small pieces. Next, fragmented endometria were mixed with a vehicle (10% DMSO) or 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 -penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranose (PGG) solution (25 mg/kg body weight in 10% DMSO) and intraperitoneally injected into the peritoneal cavity of recipient mice. Vehicle or PGG was further given two times a week for one month. For therapeutic model, one side of uteri was removed from the donor mice and fragmented into four equal size pieces after estrogen stimulation and sutured to the peritoneal wall in the same mouse. The autotransplanted lesions were allowed to grow for two weeks. Next, vehicle (10% DMSO) or 25 mg/kg body weight PGG solution (in 10% DMSO) was injected into the peritoneal cavity of the mice. Treatment was given two times a week for two weeks. The ectopic lesion and the intact uterus were dissected, weighted, and embedded by paraffin for future analysis when mice were sacrificed.

Statistical analysis

The results were presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Student's t-test was used to compare differences between two groups. Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance using a commercial statistical software (GraphPad Prism 5.02, GraphPad Software, and San Diego, CA) followed by a post-hoc analysis using Tukey's multiple analysis test. Statistical significance was set at P< 0.05.

Results

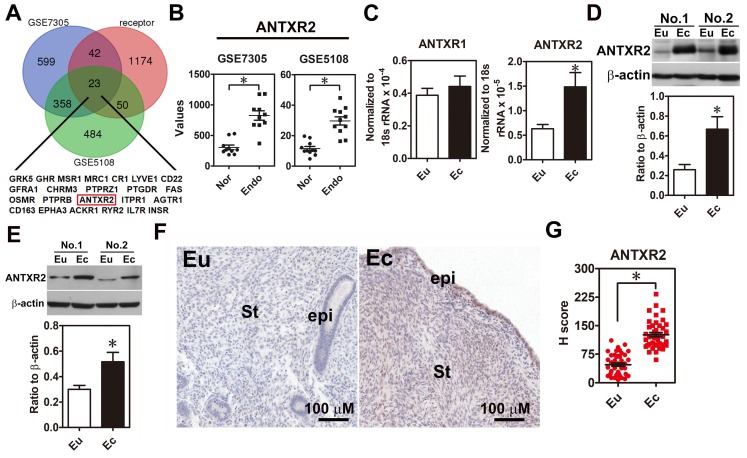

ANTXR2 is overexpressed in endometriosis

In order to systemically identify novel druggable target in endometriosis, we analyzed upregulation genes in two public datasets (GSE7305 and GSE5108), which contain microarray data of normal endometrial and endometriotic specimens and cross-referenced with a membrane receptor gene list since membrane proteins are relatively easy to be targeted. Twenty-three membrane receptors overexpressed in the endometriotic specimens were identified (Figure 1A-B). Among them, we were particularly interested in ANTXR2 because it has been shown that ANTXR2 can bind type IV collagen and laminin 10, an indication of involvement in cell adhesion. We then examined the expression levels of ANTXR2 in clinical endometriotic specimens and found that both ANTXR2 mRNA and protein were upregulated in ectopic endometriotic cells (Figure 1C-D, n=12). In contrast, levels of ANTXR1, a closely related family member of ANTXR2 in mammals, were not different (Figure 1C). Next, we isolated primary endometrial (eutopic) and endometriotic (ectopic) stromal cells from the same patient and detected ANTXR2 expression in paired stromal cells. Results showed that ANTXR2 expression was elevated in the endometriotic stromal cells (Figure 1E, n=8). Finally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for ANTXR2 revealed that ANTXR2 levels were overexpressed in the stromal cells of endometriotic lesions compared to their normal counterpart (Figure 1F-G, n=42) and were independent of menstrual cycle (Figure S2A). In eutopic endometria, the expression of ANTXR2 was similar between moderate and severe stages of endometriosis (Figure S2B). Furthermore, levels of ANTXR2 were also not different in normal endometria and eutopic endometria derived from women with endometriosis (Figure S3). Taken together, these findings indicate that we have identified a new dysregulated membrane protein, ANTXR2, in the lesion of endometriosis.

Figure 1.

ANTXR2 level was overexpressed in the endometriotic specimens. (A) Genes upregulated in ectopic endometriotic cells (p <0.05 and fold change > 1.5 fold) derived from public datasets (GSE7305 and GSE5108) were cross-referenced with a membrane receptor gene list from GO annotation. (B) Digital analysis of levels of ANTXR2 in the normal and endometriotic specimens. Raw data were retrieved from public datasets (GSE7305 and GSE5108) and analyzed by bioinformatic tools. Endo: ectopic endometriotic tissues collected from women with endometriosis. Nor: endometrial tissues collected from women without endometriosis (defined as normal); (C) ANTXR2 mRNA and (D) protein expression in our own paired samples of endometriosis (n = 12). (E) Representative Western blots (upper panel) and quantified results (lower panel) of ANTXR2 levels in paired primary stromal cells isolated from the same individuals (n = 8). (F, G) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of ANTXR2 was performed by using endometrial (n = 43) and endometriotic specimens (n = 42). ANTXR2 staining was quantified as H score. Eu: eutopic stromal cells; Ec: ectopic stromal cells. St: stromal cell; Epi: epithelial cell. The asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05 using two-tailed Student's t-test. Results were presented as means ±SEM.

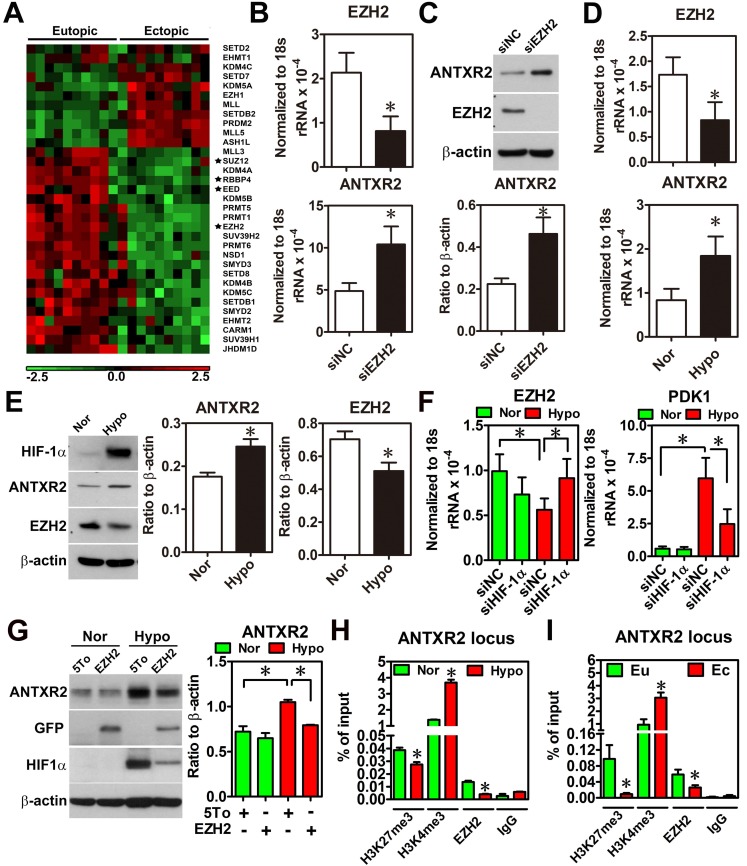

Hypoxia-repressed EZH2 causes an increase of ANTXR2 expression in eutopic stromal cells

To characterize the underlying mechanism causing ANTXR2 overexpression, we performed a thorough bioinformatic analysis of differentially expressed epigenetic factors between eutopic and ectopic endometriotic tissues, since our previous study has indicated that endometriosis is likely an epigenetic disease 13. Results showed that several components of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), such as EED, RBBP4, SUZ12 and EZH2, were markedly decreased in the endometriotic tissues compared to their normal counterparts (Figure 2A and Figure S4). Since PRC2 complex catalyzes the methylation of H3K27, a repressive mark of histone modification, reduced PRC2 components implies there is a possibility of de-repressing gene expression due to loss of H3K27 trimethylation. Then, we analyzed the Chip-on-chip dataset of anti-H3K27me3 after depletion of EZH2 in decidualized stromal cells and found that ANTXR2 was the potential target gene of EZH2 (Table S5). To test whether ANTXR2 expression is regulated by EZH2, we used siRNA to knock down EZH2 in eutopic stromal cells. Results showed that knockdown of EZH2 markedly increased ANTXR2 mRNA and protein expressions in the eutopic stromal cells (Figure 2B-C).

Figure 2.

Hypoxia-induced ANTXR2 was mediated by EZH2 downregulation. (A) Hierarchical clustering of histone methyltransferases and histone demethylase is shown as a heat map by using a public dataset containing eutopic endometrial and ectopic endometriotic tissues. Normalized probe intensity values were translated into colors with green corresponding to low expressed genes and red to high expressed genes. Stars indicate core components of PRC2. (GSE7305) (B) ANTXR2 RNA and (C) protein levels in normal eutopic stromal cells with EZH2 knocked down (n = 3) (D) Levels of ANTXR2 and EZH2 RNA and (E) protein in the normal eutopic stromal cells treated with hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 h (n = 3). (F) Levels of EZH2 and PDK1 (positive control for hypoxia) mRNA in eutopic stromal cells cultured under normoxia or hypoxia with or without HIF-1α knockdown for 24 h (n = 4). (G) Representative Western blot (left panel) and quantified result (right panel) of ANXTR2 in eutopic stromal cells overexpressed with empty vector or EZH2-GFP under normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h (n = 3). (H) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using H3K27me3, H3K4me3 and EZH2 antibodies was performed in eutopic stromal cells treated with normoxia (Nor) or hypoxia (hypo) for 48 h. Specific primers were designed to amplify ANTXR2 locus (n = 3). (I) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed in eutopic and ectopic stromal cells by using H3K27me3, H3K4me3, and EZH2 antibodies. Specific primers were designed to amplify ANTXR2 locus (n = 3). The asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05. Results were presented as means ±SEM.

Since hypoxia is a master regulator for endometriosis development 4, 14, we tested whether hypoxia is able to inhibit EZH2 expression. Results showed that hypoxia decreased EZH2 expression while increased ANTXR2 expression in the eutopic stromal cell (Figure 2D-E). Similar results were observed in chemical hypoxia (Figure S5). In addition, we also found that hypoxia-repressed EZH2 expression was mediated through the function of hypoxia inducible factor-1 α (HIF-1α) (Figure 2F). Forced expression of EZH2 under hypoxia abolished hypoxia-induced ANTXR2 upregulation (Figure 2G). Finally, to investigate the underlying mechanism of EZH2 controlling ANTXR2 under hypoxia, histone modification marks and EZH2 binding were analyzed in the ANTXR2 locus in eutopic stromal cells under normoxia or hypoxia. ChIP-qPCR data showed that hypoxia decreased EZH2 binding and H3K27me3 mark while increased H3K4me3, an active mark, in the ANTXR2 locus (Figure 2H). Similar results were also observed in ectopic endometriotic stromal cells as compared to those in eutopic stromal cells (Figure 2I), suggesting that hypoxia reprograms eutopic stromal cells to become ectopic-like stromal cells.

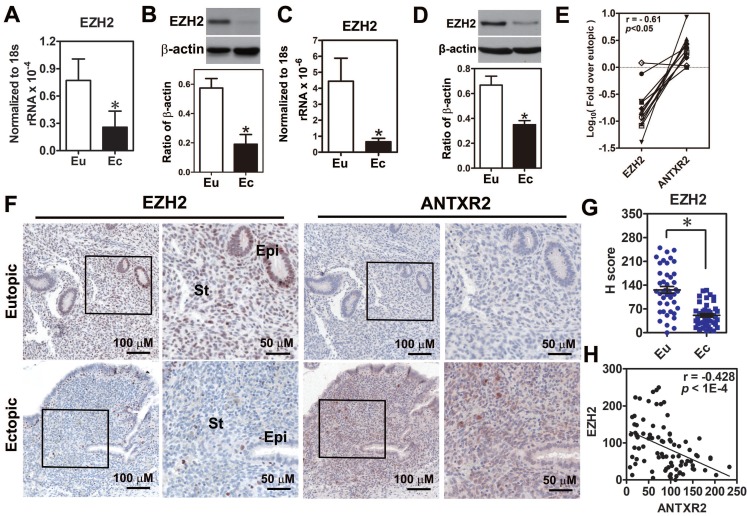

EZH2 expression is significantly decreased and negatively correlated with ANTXR2 expression in endometriotic specimens and stromal cells

Because the function of EZH2 in endometriosis is still unclear, we first investigated EZH2 expression in endometriotic specimens. Results demonstrated that EZH2 mRNA and protein were reduced in the endometriotic tissues compared to normal tissues (Figure 3A-B). Similar results were also observed in the primary ectopic stromal cells (Figure 3C-D). Further analysis revealed that EZH2 mRNA expression had a negative correlation with ANTXR2 mRNA level (Figure 3E). Immunohistochemical staining results showed that EZH2 was highly expressed in the epithelial and stromal cells of eutopic endometrial tissue but barely detected in epithelial and stromal cells of ectopic endometriotic tissue (Figure 3F-G). In contrast, ANTXR2 expression was greater in endometriotic cells compared to their eutopic counterparts (Figure 3F). Quantification results showed that EZH2 and ANTXR2 expression levels were negatively correlated with each other (Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

Loss of EZH2 expression had a negative correlation with ANTXR2 level in endometriotic specimens. (A) Levels of EZH2 mRNA (n = 12) and (B) protein (n = 8) in paired eutopic (Eu) and ectopic (Ec) endometrial specimens. (C) Levels of EZH2 mRNA (n = 5) and (D) protein (n = 5) in the primary isolated eutopic and ectopic stromal cells. (E) EZH2 and ANTXR2 mRNA levels were presented as fold over eutopic tissues. EZH2 and ANTXR2 levels from the same patient were linked by a solid line (n = 12). (F) EZH2 and ANTXR2 IHC staining were individually performed by using eutopic (n = 43) and endometriotic (n = 42) specimens. Representative IHC pictures of EZH2 (left panel) and ANTXR2 (right panel) were showed as two magnifying power, respectively. (G) EZH2 staining was quantified as H score. Eu: eutopic stromal cells; Ec: ectopic stromal cells. St: stromal cell; Epi: epithelial cell. (H) The correlation analysis by using EZH2 and ANTXR2 H scores including eutopic and ectopic specimens (n = 85). The asterisk indicates P < 0.05. Results were presented as means ±SEM.

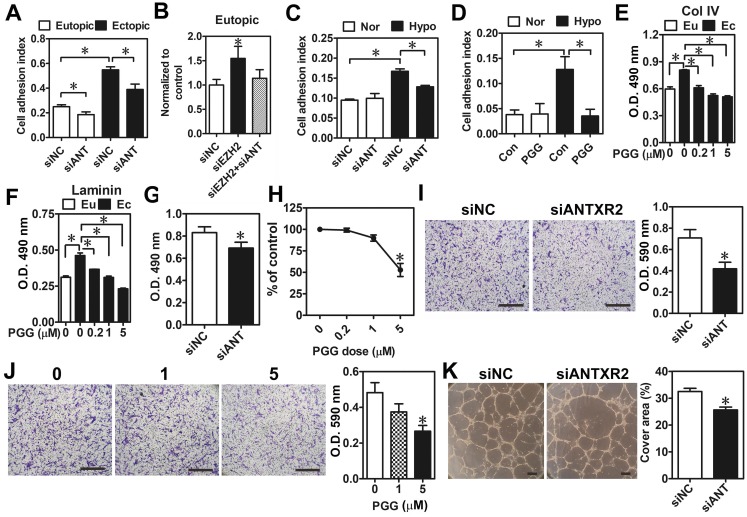

Knockdown of ANTXR2 expression decreases cell adhesive ability in the ectopic stromal cells

Next, we aimed to characterize biological functions of ANTXR2 and their impacts on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Genome-wide correlation analysis was performed by using a large cohort dataset of endometriosis (GSE51981) deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Genes having positive statistical correlations with ANTXR2 levels were clustered according to Gene Ontology. Interestingly, results showed that ANTXR2-associated genes are mainly involved in cytoskeleton remodeling, cell adhesion, angiogenesis, and cell proliferation (Table S6). To validate the bioinformatic findings, ANTXR2 was knocked down by siRNA in eutopic and ectopic stromal cells, and cell attachment ability was analyzed using the real-time cell analysis (RTCA) approach. Results showed that ectopic stromal cells indeed had a greater adhesive ability than eutopic stromal cells and the knockdown of ANTXR2 reduced it in both cell types (Figure 4A). As expected, the knockdown of EZH2 increased cell adhesive ability, which was diminished when ANTXR2 was knocked down (Figure 4B). Similarly, hypoxia increased eutopic stromal cell adhesive ability and the knockdown of ANTXR2 attenuated hypoxia-induced cell adhesive ability (Figure 4C). Similar results were observed by using PGG, an ANTXR2 inhibitor (Figure 4D). It has been known that both collagen type IV and laminin are endogenous ligands for ANTXR2 15. Therefore, collagen type IV or laminin was individually coated on the culture plate to mimic a real adhesive microenvironment; cell attachment ability was measured in the presence or absence of PGG. Results showed that treatment with PGG decreased the adhesive ability of ectopic stromal cells to collagen type IV- and laminin-coated surfaces (Figure 4E-F).

Figure 4.

Effects of ANTXR2 on cell adhesion, migration, and angiogenesis. (A) ANTXR2 was knocked down by siRNA (40 nM) for 48 h in both eutopic and ectopic stromal cells (n = 3). Real-time cell analysis (RTCA) was used to analyze adhesion ability change in those cells. (B) Eutopic stromal cells (n = 4) with single-knockdown of EZH2 (siEZH2) or double-knockdown of EZH2 and ANTXR2 (siEZH2 + siANT) were analyzed by RTCA to determine cell adhesion ability. (C) Eutopic stromal cells pre-treated with control or ANTXR2 siRNA (40 nM) for 24 h and subsequently cultured under normoxia (Nor) or hypoxia (Hypo) for another 24 h. Cells were then subjected to adhesion ability analysis by RTCA (n = 4). (D) Eutopic stromal cells were cultured under normoxia (Nor) or hypoxia (Hypo) with or without 1 μM PGG treatment for 24 h. Cells were then subjected to adhesion ability analysis by RTCA (n = 4). (E) Ectopic stromal cells were plated in the dish coating with 0.5 mg/mL collagen type IV (Col IV) or (F) 0.5 mg/mL Laminin and treated with different doses of PGG (0.2, 1, and 5 μM) for 24 h. Eutopic stromal cells were cultured in un-coated dish as a control. Cells were then subjected to adhesion ability analysis (n = 3). Asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05. (G-K) ANTXR2 in ectopic stromal cells were knocked down by siRNA for 48 h or treated with different doses of PGG for 48 h and (G, H) cell proliferation (n = 5), (I, J) migration (n = 4), and (K) tube formation (n = 3) abilities were analyzed. Asterisk indicates P < 0.05. Results were presented as means ±SEM. Scale bar: 200 μm.

As bioinformatic analysis revealed that ANTXR2-assocaited genes may contribute to cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis, we thus tested whether these biological processes were indeed regulated by ANTXR2 signaling. As shown in Figure 4E-H, knockdown of ANTXR2 and treatment with PGG inhibited ectopic endometriotic stromal cell proliferation (Figure 4G-H) and migration (Figure 4I-J). In vitro tube formation assays further showed that blocking ANTXR2 signaling attenuated angiogenetic ability (Figure 4K). Taken together, these results demonstrate that ANTXR2 plays crucial roles in the development of endometriosis.

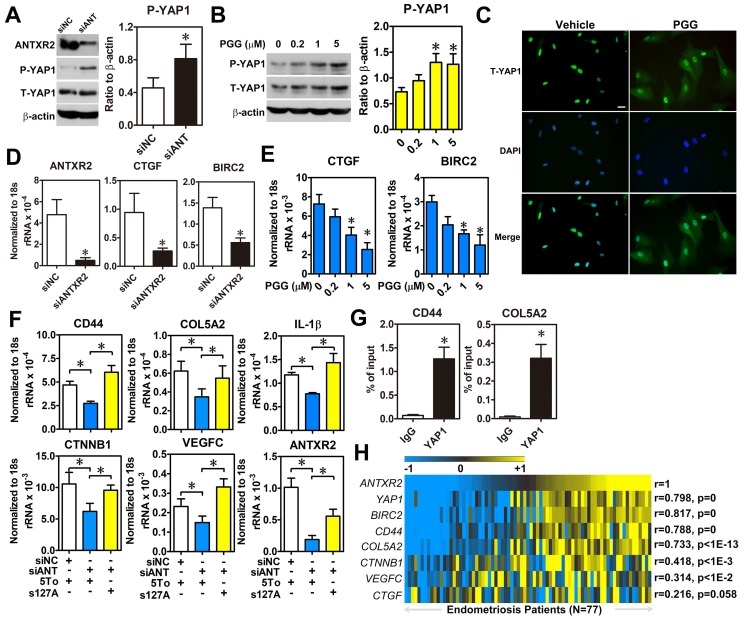

ANTXR2 increases YAP1 nuclear translocation and transactivation activity

Since the intracellular signaling pathway of ANTXR2 is largely uncharacterized, we employed bioinformatic analysis to profile genes having positive correlation with ANTXR2 to predict possible signaling pathways. The results revealed several potential ANTXR2-regulated signaling pathways (Table S7). Among them, the Hippo signaling pathway caught our eyes as we had previously shown that aberrant expression of YAP1 markedly affects pathological processes of endometriosis 16. To test whether ANTXR2 can regulate the Hippo pathway, ANTXR2 was knocked down in ectopic stromal cells and YAP1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation status were measured. Western blot results showed that knockdown of ANTXR2 increased YAP1 phosphorylation in ectopic stromal cells (Figure 5A). Similar results were observed when ectopic stromal cells were treated with different doses of PGG (Figure 5B). Since YAP1 phosphorylation will inhibit YAP1 nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity, we then tested cellular distribution of YAP1 in PGG-treated ectopic endometriotic stromal cells. Results of immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated that PGG treatment indeed retained YAP1 in the cytosol compared to the vehicle treatment (Figure 5C). Similarly, plating of endometrial stromal cells on laminin and collagen type IV-pre-coated dishes stimulated YAP1 nuclear translocation, which was blocked by PGG treatment (Figure S6). Furthermore, both knockdown of ANTXR2 and treatment with PGG significantly reduced YAP1 downstream target gene such as CTGF and BIRC2 expressions in ectopic stromal cells (Figure 5D-E). In a parallel experiment, we knocked down ANTXR2 and transfected YAP1-S127A, a kinase-insensitive mutant form, to rescue YAP1's function in ectopic stromal cells. Results showed that the levels of CD44, COL5A2, CTNNB1, IL-1β, and VEGF-C were decreased after ANTXR2 knockdown, and their expressions were restored when YAP1 was re-expressed in the ANTXR2 knockdown cells (Figure 5F). As a proof of concept, YAP1-ChIP PCR was performed to show that YAP1 was indeed bound to the loci of two candidate genes, CD44 and COL5A2 (Figure 5G). Finally, we analyzed a large cohort dataset of endometriotic specimens to provide the clinical relevance of ANTXR2 in endometriosis. Heatmap results demonstrated that ANTXR2 expression had positive correlations with YAP1, CD44, COL5A2, CTNNB1, and VEGF-C levels in the endometriotic specimens (Figure 5H), suggesting that our in vitro findings have the clinical evidence to support it. Taken together, ANTXR2 activates YAP1 and contributes to increased cell migration, angiogenesis, and adhesive ability through transcriptional regulation of several YAP1 downstream target genes in endometriosis.

Figure 5.

ANTXR2 promotes YAP1 activation via inhibition of Hippo pathway. (A) ANTXR2 was knocked down by siRNA (40 nM) for 48 h in ectopic stromal cells. Representative Western blots (left panel) showed the levels of ANTXR2, phosho-YAP1 (P-YAP1), and total-TAP1 (T-YAP1) in ectopic stromal cells. Quantified results (right panel) showed the ratio of phosho-YAP1 (P-YAP1) and total-TAP1 (T-YAP1) in ectopic stromal cells (n = 3). (B) Representative Western blots (left panel) and quantified result (right panel) showed the levels of phosho-YAP1(P-YAP1) and total-TAP1 (T-YAP1) in ectopic stromal cells treated with different doses of PGG for 24 h (n = 3). (C) Immunocytochemistry staining shows the retention of YAP1 in cytosol of cells treated with PGG. Cells were treated with 10% DMSO or PGG (5 μM in 10%DMSO) for 24 h. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D, E) Levels of YAP1 downstream target genes (CTGF and BIRC2) were analyzed in knockdown control (siNC) and ANTXR2-knocked down (siANTXR2) ectopic stromal cells (D) and PGG treated ectopic stromal cells (E) by using quantitative RT-PCR (n = 4). (F) YAP1 downstream target genes associated with cell adhesive function were analyzed in eutopic stromal cells treated with control or ANTXR2 siRNA with or without YAP1 expression construct (n = 4). (G) Ectopic endometriotic stromal cells were treated with control or siRNA against YAP1 (40 nM) for 48 h. Then, ChIP-PCR was performed to quantify the binding of YAP1 on CD44 and Col5A2 loci (n = 4). (H) Heat map shows the correlation between ANTXR2, YAP1, and its potential downstream target genes associated with cell adhesion in clinical endometriotic dataset (GSE51981). Correlation values were calculated by Pearson's correlation test. Asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05. Results were presented as means ±SEM.

ANTXR2 inhibitor blocks endometriotic lesion formation and has a therapeutic potential in the mouse model of endometriosis

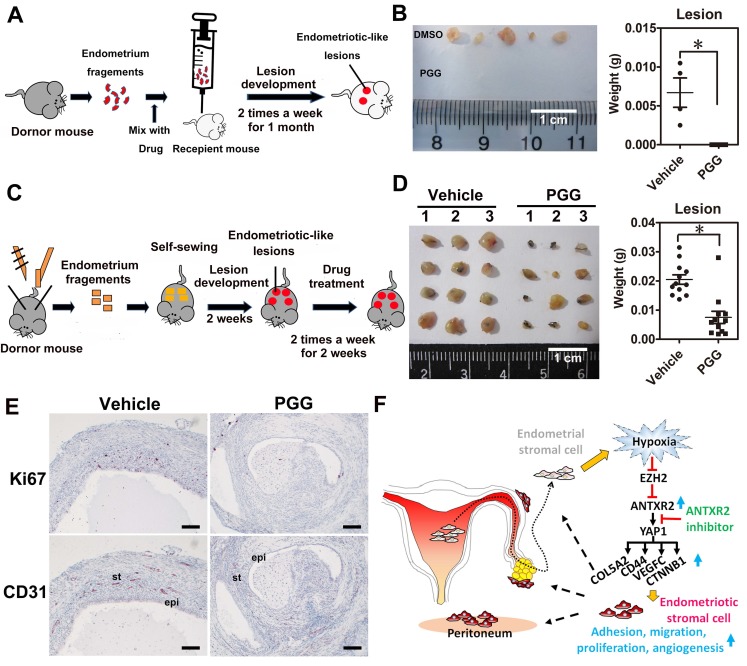

To test whether ANTXR2 inhibition could prevent the formation of endometriosis in vivo, we set up a mouse model of endometriosis by injecting endometrial fragments mixed with vehicle or PGG into the peritoneal cavity of recipient mice (Figure 6A). After transplantation, vehicle or PGG drug was administered by intraperitoneal injection twice a week for one month. Results revealed that PGG treatment totally inhibited the formation of endometriotic lesions compared to the vehicle control (Figure 6B). Next, we set up another therapeutic mouse model of endometriosis by sewing uterine fragments onto the peritoneal wall of mice to investigate the therapeutic potential of PGG (Figure 6C). Our results demonstrated that PGG treatment significantly reduced mouse endometriotic lesion weight (Figure 6D). Immunostaining showed that CD31 (blood vessel marker) and Ki67 (proliferation marker) signals were greatly reduced in the PGG-treated mouse endometriotic lesion (Figure 6E). Taken together, these findings show a crucial role of ANTXR2 in the development of endometriosis, as inhibition of ANTXR2 function prevents endometriosis formation and causes endometriotic lesion regression.

Figure 6.

ANTXR2 inhibitor markedly prevented endometriotic lesion formation and reduced lesion size in the mouse model of endometriosis. (A) A cartoon showing the brief procedures to set up the injection animal model of endometriosis. (B) A representative picture showing the lesion from vehicle group and PGG-treated group in the injection mouse model of endometriosis (left panel). Quantitative result (right panel) shows lesion weight of vehicle-treated group (n = 3 mice) and PGG-treated group (25 mg/kg, n = 5 mice). The asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05. (C) A cartoon showing the brief procedures to set up the therapeutic animal model of endometriosis. (D) A representative picture showing the lesion from vehicle group and PGG-treated group in the therapeutic mouse model of endometriosis (left panel). Quantitative result (right panel) shows lesion weight of vehicle-treated group (n = 3 mice) and PGG-treated group (25 mg/kg, n = 3 mice). Asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05. (E) Representative pictures showing CD31 and Ki67 staining results in the lesions isolated from mouse animal model of endometriosis treated with vehicle or PGG. Epi: epithelial cells. St: stromal cells; (F) A cartoon showing the current working model in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Results were presented as means ±SEM. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Discussion

Adhesion is the first and perhaps the most critical step for retrograded endometrial tissues to develop in the peritoneal cavity. However, its underlying mechanism remains elusive, despite some sporadic reports on comparing adhesive molecules such as the expression of different types of integrins between normal and endometriotic tissues. Unfortunately, the results are inconsistent, or even controversial, among the different studies 7, 17-20. Thus, we tried to identify novel and druggable targets involved in the adhesion of endometriotic lesions. Herein, we identified that ANTXR2, a membrane receptor, was overexpressed in ectopic endometriotic cells by using bioinformatics and molecular approaches. Aberrant expression of ANTXR2 was induced by hypoxia-mediated epigenetic regulation of histone modification. The signaling cascade and pathological functions of ANTXR2 were also unraveled. More importantly, we demonstrated that by pharmacologically blocking ANTXR2-mediated signaling, the development of endometriotic lesions was prevented and the established endometriotic lesion regressed.

ANTXR2 is well-known for mediating the entry of anthrax toxin into host cells 11. However, the biological and pathological roles of ANTXR2 were seldom investigated. Recently, genome-wide screening identified that genetic mutation of ANTXR2 is associated with systemic hyalinosis 21 and ankylosing spondylitis 22. Tan and colleagues also reported that ANTXR2 plays an oncogenic role in glioma 23. Our study adds another pathological function of ANTXR2 by demonstrating its critical roles in endometriosis. To our knowledge, this is the first report to clearly delineate the regulation, signaling, biological processes, and therapeutic potential of ANTXR2 in any kind of human disease.

In this study, we found that ANTXR2 is aberrantly expressed in ectopic endometriotic cells; however, the potential mechanism causing ANTXR2 dysregulation was unknown before. Based on our previous studies and bioinformatic analysis, we hypothesized that hypoxia is a critical microenvironmental factor to cause ANTXR2 upregulation. Our previous findings have demonstrated that HIF-1α is elevated in the endometriotic cells 24 and upregulation of HIF-1α regulates numerous pathological processes in the development and/or progression of endometriosis 4, 16, 25-27. Herein, we found that many epigenetic regulators were decreased in the endometriotic specimens and several of them belong to PRC2 complex. Since EZH2 is a key component of PRC2 complex and we have observed that H3K27me3 mark of ANTXR2 locus is decreased when EZH2 is knocked down by analyzing the raw data of Grimaldi et. al. 28, we reasoned that the aberrant expression of ANTXR2 may be regulated by EZH2, a histone-lysine N-methyltransferase that facilitates methylation of histone H3K27 29. Loss of EZH2 expression has been reported during the decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells and contributes to increased downstream gene expressions via a chromatin remodeling mechanism 28. Indeed, by using several different techniques and approaches, our results proved that hypoxia-induced ANTXR2 expression is mediated by the loss of EZH2 in eutopic stromal cells. The inverse correlation between ANTXR2 and EZH2 in serial sections of specimens derived from same individual (i.e., the paired eutopic and ectopic samples) provides a solid evidence to support that the overexpression of ANTXR2 in ectopic endometriotic tissues is likely due to loss of EZH2-mediated histone modification. While our project was halfway through, Zhang and colleagues reported that EZH2 expression is elevated in the endometriotic specimens, especially in epithelial cells 30, which is in contrast to our and Grimaldi's data 28. Because information about the antibodies used in Zhang's paper was not revealed, we were unable to further investigate the cause for the inconsistency between their data and our current findings. Nonetheless, our data not only show the reduction of EZH2 in ectopic endometriotic stromal cells but also mechanistically demonstrate that the downregulation of EZH2 is mediated by HIF-1α-dependent hypoxic stress. Thus, we are confident that our data are sustainable.

To investigate the potential function of ANTXR2 in endometriosis, we took the advantage of publicly available datasets and our in-house bioinformatic platform. The bioinformatic analytic results reveal that ANTXR2 may play roles in cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis. All of these processes are important for endometriotic cells to survive, especially under hypoxic stress. Indeed, we showed that the adhesive ability of eutopic stromal cells was increased under hypoxia, which is ANTXR2-dependent. During preparation of this manuscript, Lin et al. reported that hypoxia increases cell adhesive ability via TGFβ1/SMAD signaling in endometrial stromal cells 31. Their finding is consistent with ours because our data showed that TGFβ1 receptor signaling is one of the signaling pathways controlled by ANTXR2 (Table S7). Besides adhesion, our data further showed that ANTXR2 also controls cell proliferation, migration, and new blood vessel development in a cell culture system as well as in a mouse model of endometriosis. Taken together, we demonstrate the novel function of ANTXR2 in the pathogenesis of endometriosis by regulating several critical biological processes.

The intracellular signaling of ANTXR2 is largely unknown. Herein, we demonstrate that the Hippo singling pathway is regulated by ANTXR2. We have previously proved that YAP1, an effector of the Hippo pathway, is a master regulator controlling several crucial cellular processes during the development of endometriosis 16. In our current study, we further identified that several critical genes involved in cell adhesion, including CD44 and COL5A2, were the novel downstream targets of YAP1. The identification of YAP1 as a downstream effector of ANTXR2 provides the missing piece of Sampson's retrograde hypothesis about endometriosis development. The modified Sampson's model is like this: The shed endometrial tissues suffer from hypoxic stress during retrograding to peritoneal cavity. Most of the cells die because of severe hypoxic stress; however, some survive. The increase of ANTXR2 induced by hypoxia-mediated epigenetic histone modification enables these survived cells to bind to extracellular matrix components such as collagen and laminin. Once binding occurs, the extracellular matrix initiates the ANTXR2 signaling, leading to YAP1 activation and nuclear translocation, which triggers numerous biological processes needed for endometriotic cells to survive 16 and the development of endometriosis to start (Figure 6F).

Based on our findings, we set up two different mouse models of endometriosis to test whether inhibition of ANTXR2 has the preventive and/or therapeutic potential for endometriosis. Animal studies showed that blocking ANTXR2 signaling by PGG treatment not only inhibits endometriotic lesion formation in the prevention mouse model of endometriosis but also reduces endometriotic lesion size in the therapeutic mouse model of endometriosis. The therapeutic role of blocking ANTXR2 is clear, while the preventive one needs some knowledge by knowing patient's prior medical history. It is practically impossible to prevent endometriosis in women without prior diagnosis; however, the preventive idea may be applied to reduce the recurrent rate after surgery. It is known that laparoscopic excision of endometriosis has a higher recurrent rate if patients did not receive any medication after surgery 32, 33. Furthermore, abdominal surgery such as Caesarean section is associated with the induction of endometriosis formation in the abdominal wall, which is known as scar endometriosis. Clinical evidences have shown that Cesarean delivery scar is the most common site to identify abdominal wall endometriosis 34. For these situations, blocking the function of ANTXR2 by its inhibitor may reduce or even prevent surgery-induced endometriosis formation or recurrence.

Taken together, the data presented in this study reveal the pathological functions of ANTXR2 in endometriosis, the novel signaling pathway mediated by ANTXR2, and the therapeutic potential of targeting ANTXR2 for endometriosis therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report to thoroughly characterize the regulation, signaling, function, and therapeutic potential of ANTXR2. It is anticipated that targeting ANTXR2 may be an alternate, non-hormone therapy for endometriosis in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yen-Yu Lai, Yi-Chen Tang, and Yi-Shang Yeh for technical assistance. This work was supported by research grants from Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104-2320-B-006-036-MY3 and 106-2320-B-006-072-MY3 to SJT; MOST 105-2320-B-006-055-MY2 to SCL):

Contributions

SC Lin designed and performed most experiments, analyzed data, and wrote manuscript; HC Lee, CT Hsu, WN Li, YH Huang, and PL Hsu performed experiments; MH Wu performed clinical diagnosis, collected specimens, and provided critical advice of clinical knowledge; SJ Tsai conceived the project and wrote manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ANTXR2

anthrax toxin receptor 2

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- GEO

gene expression omnibus

- GO

gene ontology

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor-1 α

- PGG

1, 2, 3, 4, 6-penta-o-galloyl- β-d-glucopyranose

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- RTCA

real-time cell analysis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

References

- 1.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vercellini P, Vigano P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:261–75. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1927;14:422–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsiao KY, Lin SC, Wu MH, Tsai SJ. Pathological functions of hypoxia in endometriosis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2015;7:309–21. doi: 10.2741/E736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu MH, Shoji Y, Chuang PC, Tsai SJ. Endometriosis: disease pathophysiology and the role of prostaglandins. Expert reviews in molecular medicine. 2007;9:1–20. doi: 10.1017/S146239940700021X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisolle M, Casanas-Roux F, Donnez J. Early-stage endometriosis: adhesion and growth of human menstrual endometrium in nude mice. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:306–12. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klemmt PA, Carver JG, Koninckx P, McVeigh EJ, Mardon HJ. Endometrial cells from women with endometriosis have increased adhesion and proliferative capacity in response to extracellular matrix components: towards a mechanistic model for endometriosis progression. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:3139–47. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delbandi AA, Mahmoudi M, Shervin A, Akbari E, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Sankian M. et al. Eutopic and ectopic stromal cells from patients with endometriosis exhibit differential invasive, adhesive, and proliferative behavior. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:761–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knudtson JF, Tekmal RR, Santos MT, Binkley PA, Krishnegowda N, Valente P. et al. Impaired Development of Early Endometriotic Lesions in CD44 Knockout Mice. Reprod Sci. 2016;23:87–91. doi: 10.1177/1933719115594022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell SE, Mavila A, Salazar R, Bayless KJ, Kanagala S, Maxwell SA. et al. Differential gene expression during capillary morphogenesis in 3D collagen matrices: regulated expression of genes involved in basement membrane matrix assembly, cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation and G-protein signaling. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2755–73. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scobie HM, Rainey GJ, Bradley KA, Young JA. Human capillary morphogenesis protein 2 functions as an anthrax toxin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5170–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0431098100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu S, Crown D, Miller-Randolph S, Moayeri M, Wang H, Hu H. et al. Capillary morphogenesis protein-2 is the major receptor mediating lethality of anthrax toxin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12424–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905409106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao KY, Wu MH, Tsai SJ. Epigenetic regulation of the pathological process in endometriosis. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16:314–9. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HC, Tsai SJ. Endocrine targets of hypoxia-inducible factors. J Endocrinol. 2017;234:R53–R65. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deuquet J, Lausch E, Superti-Furga A, van der Goot FG. The dark sides of capillary morphogenesis gene 2. EMBO J. 2012;31:3–13. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin SC, Lee HC, Hou PC, Fu JL, Wu MH, Tsai SJ. Targeting hypoxia-mediated YAP1 nuclear translocation ameliorates pathogenesis of endometriosis without compromising maternal fertility. The Journal of pathology. 2017;242:476–87. doi: 10.1002/path.4922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regidor PA, Vogel C, Regidor M, Schindler AE, Winterhager E. Expression pattern of integrin adhesion molecules in endometriosis and human endometrium. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4:710–8. doi: 10.1093/humupd/4.5.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khorram O, Lessey BA. Alterations in expression of endometrial endothelial nitric oxide synthase and alpha(v)beta(3) integrin in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:860–4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puy LA, Pang C, Librach CL. Immunohistochemical analysis of alphavbeta5 and alphavbeta6 integrins in the endometrium and endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:167–77. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannelli G, Sgarra C, Di Naro E, Lavopa C, Angelotti U, Tartagni M. et al. Endometriosis is characterized by an impaired localization of laminin-5 and alpha3beta1 integrin receptor. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:242–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shieh JT, Swidler P, Martignetti JA, Ramirez MC, Balboni I, Kaplan J. et al. Systemic hyalinosis: a distinctive early childhood-onset disorder characterized by mutations in the anthrax toxin receptor 2 gene (ANTRX2) Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1485–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australo-Anglo-American Spondyloarthritis C, Reveille JD, Sims AM, Danoy P, Evans DM, Leo P. et al. Genome-wide association study of ankylosing spondylitis identifies non-MHC susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:123–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan J, Liu M, Zhang JY, Yao YL, Wang YX, Lin Y. et al. Capillary morphogenesis protein 2 is a novel prognostic biomarker and plays oncogenic roles in glioma. J Pathol. 2018;245:160–71. doi: 10.1002/path.5062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu MH, Chen KF, Lin SC, Lgu CW, Tsai SJ. Aberrant expression of leptin in human endometriotic stromal cells is induced by elevated levels of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:590–8. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsiao KY, Chang N, Lin SC, Li YH, Wu MH. Inhibition of dual specificity phosphatase-2 by hypoxia promotes interleukin-8-mediated angiogenesis in endometriosis. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2014;29:2747–55. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsiao KY, Chang N, Tsai JL, Lin SC, Tsai SJ, Wu MH. Hypoxia-inhibited DUSP2 expression promotes IL-6/STAT3 signaling in endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol; 2017. p. 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsiao KY, Wu MH, Chang N, Yang SH, Wu CW, Sun HS. et al. Coordination of AUF1 and miR-148a destabilizes DNA methyltransferase 1 mRNA under hypoxia in endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2015;21:894–904. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gav054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimaldi G, Christian M, Steel JH, Henriet P, Poutanen M, Brosens JJ. Down-regulation of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 contributes to the epigenetic programming of decidualizing human endometrial stromal cells. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md. 2011;25:1892–903. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P. et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, Dong P, Liu X, Sakuragi N, Guo SW. Enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in endometriosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6804. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06920-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin X, Dai Y, Xu W, Shi L, Jin X, Li C. et al. Hypoxia Promotes Ectopic Adhesion Ability of Endometrial Stromal Cells via TGF-beta1/Smad Signaling in Endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2018;159:1630–41. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-03227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koga K, Takemura Y, Osuga Y, Yoshino O, Hirota Y, Hirata T. et al. Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after laparoscopic excision. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2171–4. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouchi N, Akira S, Mine K, Ichikawa M, Takeshita T. Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after laparoscopic excision: risk factors and prevention. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:230–6. doi: 10.1111/jog.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan Z, Zanfagnin V, El-Nashar SA, Famuyide AO, Daftary GS, Hopkins MR. Risk Factors, Clinical Presentation, and Outcomes for Abdominal Wall Endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:478–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.