1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The rates of older adults with a functional disability related to frailty have been estimated to be about 30% in adults ages 80 and older (Fried et al., 2004). Frailty is a unique health condition characterized by a symptom cluster including fatigue, decreased physical activity, weight loss, grip strength, and slowed gait (Fried et al., 2001). Both cognitive impairment and physical frailty independently lead to increased disability, falls, mortality, an increase in health service need, and high direct/indirect costs to healthcare, often long-term care and hospitalization (Fried et al., 2001; Global Health and Aging, 2015). A growing body of evidence suggests that factors such as mental health and cognition may influence the frailty status of an older adult (Brown et al., 2014; Gray et al., 2013; Han et al., 2014). Frail older adults with cognitive impairment who have a fivefold increase (HR, 5.12) in mortality risk, a twelvefold increase (OR, 12.2) in functional disability, and lower quality of life compared to individuals with isolated frailty or cognitive impairment (Feng et al., 2017). The relationship between physical frailty and cognitive impairment with evidence of an interrelated neuropathology (Buchman et al., 2014; Lista and Sorrentino, 2010) may provide a means to identify individuals with cognitive impairment caused by non-neurodegenerative conditions that might be reversible (Buchman and Bennett, 2013; Kelaiditi et al., 2013; Solfrizzi et al., 2017). Although frailty and cognitive impairment have been shown to be related, both constructs have long been studied separately (Kelaiditi et al., 2013).

1.2. Conceptual frameworks

Several researchers have suggested new conceptual frameworks such as motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR) and “cognitive frailty” to provide stimulus for new research into understanding the shared pathology (Kelaiditi et al., 2013; Verghese et al., 2013). MCR is described as both slow gait and the presence of subjective cognitive complaints and has been associated with an increased risk of developing dementia (Verghese et al., 2013, 2014). The loss of muscle mass involving decreased muscle fibers called sarcopenia can lead to changes in gait and physical performance in older adults. The International Consensus Group organized by the International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (I.A.N.A) and the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (I.A.G.G) convened in 2013 to identify related domains of physical frailty and cognition. The International Consensus Group (I.A.A.A. /I.A.G.G.) report is an acknowledgment of the need to focus research efforts on a clinical condition characterized by the co-occurrence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment, in absence of overt dementia diagnosis or underlying neurological conditions (Kelaiditi et al., 2013). The “cognitive frailty” construct is considered a heterogeneous clinical syndrome in older adults with evidence of: 1) physical frailty and cognitive impairment (Clinical Dementia Rating score of 0.5); and 2) exclusion of a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease or other dementia (Kelaiditi et al., 2013). Cognitive frailty can be considered a geriatric syndrome in which we see a cluster of individuals with a condition which simultaneously presents with both physical frailty and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Kelaiditi et al., 2013; Panza et al., 2006). However, the mechanisms and the directional relationship behind the dynamic association of these two constructs remains unexplained. There exists evidence for the association of frailty and cognitive impairment suggesting shared pathophysiological mechanisms such as vascular disease that influence both clinical manifestations (Buchman and Bennett, 2013; Panza et al., 2006). Although, some research has been conducted on the association between physical function and cognitive impairment there is still no comprehensive list or understanding of the underlying mechanisms for cognitive frailty. Identification of emerging biomarkers from studies of sarcopenia, physical frailty, and cognitive impairment will help distinguish between changes related to normal aging, irreversible pathological process, and specific neurological diseases that may be reversible and establish a reliable research criteria for a novel clinical construct (Blazer et al., 2015; Solfrizzi et al., 2017).

1.3. Purpose

In the past century, scientific research has been driven by molecular science with the common goal of identifying a single group of biological or genetic mechanisms as the cause of disease. We now understand that the mechanisms underlying disease processes are multi-factorial and system based. Therefore, efforts to unravel this complexity start with understanding the unique biological factors that discriminate between conditions, as well as shared biological mechanisms in individuals presenting with similar symptoms and trajectories. Although, some research has been conducted on the association between physical function and cognitive impairment there is still no comprehensive list or understanding of the underlying mechanisms for this relationship. Because both cognitive impairment and frailty are large heterogeneous conditions it may not be possible to identify one biomarker to measure both. The use of one or more biomarkers specific to both constructs will improve our understanding of the association (Biomarkers Definitions Working Group, 2001; Mayeux, 2004). It is possible that the underlying biological mechanisms are at the intersect between cognitive impairment and frailty or cognitive frailty may contain some of its own unique markers of disease. The purpose of this review is to examine biological and genomic factors for cognitive impairment and frailty as a method for identifying shared mechanisms for these two important aging conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Systematic review

The rational for conducting a systematic review was to further develop an understanding of the shared pathology by determining the relevant biomarker data as defined by the National Institutes of Health Biomarkers Definitions Working Group (Biomarkers Definitions Working Group, 2001) for both cognitive impairment and frailty using the cognitive frailty framework (Kelaiditi et al., 2013).

2.2. Search strategy

In this review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines(Shamseer et al., 2015). A systematic review of the literature was performed using the following online databases: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, LILACS, Gene Indexer, and GWAS Central. For reproducibility, we have provided the PubMed search strategy in the Supplementary Appendix (Table A). A systematic review of the literature was performed from studies published from the start date of the database till 29 December, 2017. In addition to database searching, articles were hand-pulled from references and identified through other sources.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that included information on biomarkers or genetic markers for dementia, frailty, sarcopenia, or cognitive frailty were included. Reviews, animal studies, imaging biomarkers, and case studies were excluded. Studies on a geriatric population, aged 65 and older, were included. Articles about other disease states such as cancer, Multiple Sclerosis, Down Syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Huntingdon’s disease were excluded. Only articles published in English were included. See Supplementary Appendix Table A.

2.4. Study appraisals

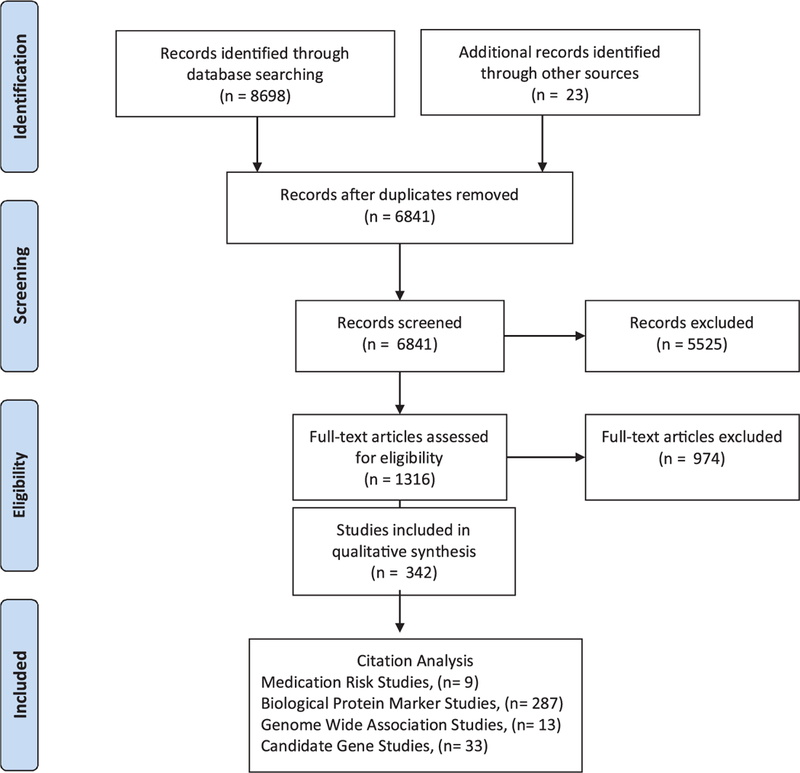

A multi-step approach was used to evaluate relevant articles using Covidence, a web-based software platform selected by Cochrane Reviews that organizes and streamlines the systematic review process (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, 2016). Fig. 1 shows the stages (PRISMA) for retrieving the studies for inclusion and extraction. We conducted a review of the titles and abstracts of all the papers identified through database searching and hand pulling from references lists. Three reviewers participated in this step and each article was reviewed by two reviewers to ensure interrater reliability. A third reviewer resolved conflicting assessments. A fourth reviewer was available for additional arbitration however their services were not required.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection and citation analysis.

2.5. Extraction

The analysis for this paper was generated using Qualtrics software, Version 9.2017 of Qualtric (Copyright © [2017] Qualtrics). Qualtrics and all other Qualtrics product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA. http://www.qualtrics.com.) The survey created in Qualtrix (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) ensured consistency in reporting of biological markers limiting open text boxes, consistent categorizing of biomarkers by clinical, genetic, and fluid markers in the following categories: inflammatory/immunity, laboratory, protein, metabolomics, oxidative stress markers. The database assigned each biomarker a unique numeric code (i.e. IL6 = 3, CRP = 27). Biomarkers were extracted with a p-value ≤ .05 and genomic data extraction included: gene, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), chromosome, and effect/minor allele. When data entry was complete, the final data frame was exported from Qualtrix and analyses was carried out using R V. 3.2.1. R is a free, open-source software that provides many statistical and graphic techniques. R packages used included ‘MASS’ and ‘ggplot2’ (Ripley et al., 2017; Wickham and Chang, 2017).

We did not complete a formal method of assessment for the quality of the studies with a meta-analysis given that the goal of this review is to identify potential putative makers for a new phenotype “cognitive frailty”. Level of evidence was appraised for longitudinal, observational (cohort, cross Sectional, case-control studies), and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) using the Center for Evidence Based Medicine Levels of Evidence (OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group, 2011). Additionally, there are limited (RCTs) for frailty and none for cognitive frailty. We do provide a compressive list of the principle results, study design, and detail list of genetic findings correlated to one of the following phenotypes: cognitive impairment, frailty, and cognitive frailty. The markers extracted for correlation to cognitive frailty were identified by the reviewers to be studies that explored both frailty and cognitive impairment in the same study.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

From 6841 articles identified, titles and/or abstracts reporting on information pertaining to biomarkers or genetic markers for cognitive impairment, frailty, or cognitive frailty were included. 1316 potential relevant articles were chosen for closer review, two reviewers with appropriate subject expertise assessed the full-text of the articles for relevancy. 342 full-text articles reporting on the relevant topic met inclusion/exclusion criteria and 974 articles were excluded. Reviewer disagreements were addressed in regular meetings and resolved. A total of 342 articles were used to extract the clinical, genetic, and protein markers for three phenotypes: cognitive impairment, frailty, and cognitive frailty. Studies were reviewed in the following categories 46 genetic studies: 13 genome wide association study (GWAS) and 33 candidate gene studies, 287 biological protein studies, 9 medication risk studies. Additional study designs included observational (Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies), longitudinal, RCT and In Vitro studies. For the 13 studies that included both a longitudinal and observational (Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies) study design we extracted markers from both study designs. The studies were categorized by phenotype: cognitive impairment (n = 248), frailty (n = 75), cognitive frailty (n = 15). Only one GWAS study included both cognitive and physical function measures however, the study did not use a standardized frailty tool (Thibeau et al., 2017). Phenotypes were further defined by the type of cognitive impairment (i.e. Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment), component of frailty (i.e. gait, sarcopenia, grip strength, physical activity) as stated in the study or a combination of both was considered cognitive frailty. Operational definitions for the frailty and cognitive frailty phenotypes differed among studies; the frailty phenotype (n = 32) using the Cardiovascular Heart Study measures (Fried et al., 2001) and Rockwood’s Frailty Index (n = 2) where the most common frailty measures. The Supplementary appendix (Table B) shows the complete list of phenotypes, frailty measures, clinical, and protein biomarkers extracted. Tables 1–3 show the biomarkers extracted by phenotype in the following categories: clinical, inflammatory/immunity, laboratory, protein, metabolomics, and oxidative stress.

Table 1.

Cognitive decline biomarkers by category.

| Inflammatory/Immunity Markers | Laboratory Markers | Protein Markers | Metabolomics Markers | Oxidative Stress Markers | Clinical Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein IL6 Homocysteine |

Albumin Olfactory marker Ocular marker Aβ 1–42 |

Aβ 1–40/t-tau ratio Aβ42 Aβ 1–42 |

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) Sphingolipid-SM(d18:1/18:0) sphingomyelin [SM(39:1)] |

F2-isoprostanes/ isoprostanes Choline plasmalogen(PlsCho) Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) |

Elevated blood pressure Anticholinergic Medications Body Mass Index |

| Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) | Folate | PhosphoTaul81 (P-tau 181) | SM/ceramide ratio | Total antioxidant status (TAS) |

Alcohol Intake |

| YKL-40 (neuroinflammation or Chitinase-3 ChI3L3) | Creatinine | P-tau | SM/ceramide ratio | Peroxisomal b-oxidation levels |

Elevated Systolic pressure |

| Cortisol | Cobalamin deficiency (B12) | Aβl-42/ Aβl-40 ratio | PC aa 36:1 Glycerophospholipids | Ethonalamin plasmalogen (PlsEtn) |

Elevated diastolic pressure |

| IL8 TNF-a receptor I (TNFR1) |

Platelet distribution width (PDW) Nutrient biomarker patterns (NBP) |

Aβ 1–40 P-tau231 |

PC aa 32:0 Glycerophospholipids PC 16:0/20:5 phosphatidylcholine |

PLsCho + PlsEtn PLsCho/PlsEtn Ratio |

Increase waist circ/waist-to-hip Change in resting hear rate |

| Fibrinogen | Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | Aβ40 | PC 16:0/22:6 phosphatidylcholine |

Plasmalogen | Cardiovascular disease |

| Uric Acid | Methylmalonic acid (MMA) | P-taul81/Aβ42 | PC 18:0/22:6 phosphatidylcholine |

Protein carbonyls | Benzodiazepine medications |

| Monocyte chemotactic Protein-2 (MCP-2) | Glucose | Cystatin C | Ceramides C16:0 | Malondialdehyde (MDA) | Angiotensin converting enzyme medications |

| Resistin | Insulin resistance (IR-HOMA) | t-tau/ Aβ42 | Ceramides C20:0 | Psychoactive medications | |

| IL10 | Lipids: Triglycerides | Aβ 1–42/t-tau ratio | Ceramides C22:0 | Low level of education | |

| ILlbeta | Lipids: LDL cholesterol | Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoAl) | Ceramides C24:0 | Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) |

|

| IL17E | Lipids: HDL cholesterol | Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) |

Ceramides C26:0 | Activities of daily living (ADLs) | |

| Clusterin | Free Testosterone | Lysosomal-associated membrane | Stearoyl | ||

| protein 1 (LAMP-1) | |||||

| TNF-a receptor II (TNFR2) Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) Cortisol/Dehydroepiandrosterone ratio |

Insulin like growth factor protein (IGF-1) Insulin like growth factor protein (IGF-2) Insulin like growth factor protein Binding Protein (IGFBP-2) |

sAβ/APP ratio Aβ42/ Aβ40 Neurofilament light chain (NFL) |

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) | ||

| Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) | Insulin like growth factor protein Binding Protein (IGFBP-3) |

Apolipoprotein A-II (ApoA2) | |||

| Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) |

Anemia | Complement factor H (CFH) protein 1 | |||

| Plasma Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) | Hemoglobin | Chromogranin A (CgA) | |||

| alpha 2-macroglobulin (A2M) | Polyunsaturated fatty acids (O3PUFAs)/ n-6/n-3 ratio |

Visinin-like protein-1 (VILIP-1) | |||

| Adiponectin | alpha-1-antichymotrypsin (ACT) | β-secretase (BACE-1) | |||

| IL1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) |

Ubiquitin | |||

| IL6R | Peroxidase | Heat shock protein 70 | |||

| IL13 | Creatinine Clearance | Epidermal growth factor (EGF) | |||

| IL1RA | N-acetylaspartate (NAA)/creatine (Cr) | Pancreatic peptide (PP) | |||

| IL7 | Methylcitric acid (MCA) | Soluble amyloid β protein (sAβ) | |||

| IL12p70 | Holotranscobalamin (holoTC) | Amyloid β precursor protein (APP) | |||

| D-dimer | Glycohemoglobin (HbA1c) | Aβ 1-42/p-tau ratio | |||

| Procalcitonin | Lipids: Total Cholesterol | P-tau231/Aβ42/40 ratio | |||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 24S-hydroxycholesterol | T-tau/Aβ42/40 ratio | |||

| GlycA | Aspartate transaminase (AST) | Apolipoprotein C2 | |||

| Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP 1α) | Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP 1α) | Apolipoprotein H | |||

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) | Total Testosterone | ApoB/ApoA1 ratio | |||

| Serum Amyloid A | Total Bilirubin | A1AcidG | |||

| Fibrinogen gamma-chain | Vitamin E | Transthyretin (TTR) | |||

| Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) | Vitamin D | Ceruloplasmin | |||

| Adhesion molecule soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) |

Vitamin C | Cathepsin D | |||

| Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) |

Beta-Carotene | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3-α) | |||

| Neutrophil/Lymphocyte ratio | Calcium | Neuronal Cell Adhesion Molecule (NrCAM) |

|||

| Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) | Nitrate2+Nitrate3 | Axl receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL) | |||

| CD40 | Selenium | VILIP-1/Abeta1-42 | |||

| IgG2 | Hematocrit | Sirtuin/SIRT1 | |||

| IgA | Mean platelet volume (MPV) | Aβ/β-actin | |||

| P-selectin | Transferrin | α-secretase (ADAM10) | |||

| Matrix Metalloproteinase-10 (MMP-10) | Haptoglobin | Rab3 | |||

| Chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) (protein2 list) | White blood cells (WBC) | Rab7 | |||

| Beta 2-microglobulin (B2M) | Total Urinary polyphenols (TUPs) | Early Endosome Marker (EEA1) | |||

| FAS ligand belongs to TNF family | Alpha-1-antitrypsin (alpha1-AT) | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP-2) |

|||

| CD8 | Lactoferrin (LTF) | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/ 1B-light chain 3 (LC3) |

|||

| N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) |

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) | ||||

| Luteinizing hormone (LH) | Carcinoembryonic antigen Osteoprotegerin (OPG) Neruogranin (NGRN) Cellular prion protein (PrPc) Kidney Injury Molecule (KIM-1) Growth-regulated alpha protein (GRO-α) Unfolded p53 P-t181p/Ab1-42 ratio |

||||

Table 3.

Cognitive frailty biomarkers by category.

| Inflammatory/Immunity Markers | Laboratory Markers | Protein Markers | Clinical Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein | Creatinine Clearance | Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA1) | Body Mass Index |

| IL6 | Cobalamin deficiency (B12) | Prostaglandin F2-alpha | > 2 chronic diseases |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) | Insulin like growth factor protein (IGF-1) | Apolipoprotein B | Income |

| IL8 | Vitamin D | Low level of education | |

| IL1beta | White blood cells (WBC) | Alcohol intake | |

| IL1alpha | Albumin | Elevated blood pressure | |

| Fibrinogen | Creatinine | Elevated systolic pressure | |

| CD8 | Glucose | Cardiovascular disease | |

| Homocysteine | Glycohemoglobin (HbA1c) | Psychoactive medications | |

| Cortisol | Lipids: LDL cholesterol | Depression | |

| CD4 | Alpha-linolenic acid | Activities of daily living (ADL) | |

| Circulating Osteogenic Progenitor (COP) cells | Sodium | Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) | |

| Intercellular Adhesive Molecule-1 | Monocytes | ||

| Neutrophils | |||

| Urate | |||

| Glucose | |||

| Total protein | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | |||

| Calcium | |||

| Lipids: Triglycerides | |||

| Lipids: Total Cholesterols | |||

| Free thyroxine, fT4 | |||

| Ferritin, | |||

| Lipids: HDL cholesterol | |||

| Free thyroxine, fT3 | |||

| Red blood cells (RBC) | |||

| White blood cells (WBC) | |||

| Lymphocytes | |||

| Hemoglobin | |||

| Phosphate | |||

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (O3PUFAs)/ n-6/n-3 | |||

| ratio | |||

| Hematocrit | |||

3.2. Clinical markers

Several of the studies reported clinical findings associated with cognitive impairment, frailty, and cognitive frailty. Demographics such as increasing age was a factor for all phenotypes, lower education and income were factors for individuals with cognitive impairment and frailty. Other clinical markers included: measures of cardiovascular disease, elevated blood pressure, multiple co-morbidities, changes in body mass index (BMI), and alcohol intake. One of the most interesting clinical findings was an association between medications and all phenotypes. These included hypertension, benzodiazepine, anticholinergic, and psychoactive medications. Two categories of hypertensive medications beta-blockers (i.e. metoprolol and atenolol) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors were found to have the most significant effect on cognitive impairment (Lanctôt et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2014). Additionally, there was a significant interaction between ACE inhibitor use and carriers of ApoE4 (odds ratio: 20.9, 95% CI 3.08–140.95, p = .002) (Qiu et al., 2014). Anticholinergic burden was found to be associated with cognitive impairment and frailty. Many of the medications used to control multiple chronic conditions in older adults (e.g., depression, hypertension, and heart failure) have unintended anticholinergic effects on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the central and peripheral nervous system (Nishtala et al., 2016; Salahudeen and Nishtala, 2016). The cumulative effects of these unintended anticholinergic properties are referred to as anticholinergic burden (ACB) (Fox et al., 2014; Jansen and Brouwers, 2012; Nishtala et al., 2016). For every ACB medication added, the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) score decreases 0.33 points over 2 years, risk of cognitive decline is 46% over 6 years (Campbell et al., 2010; Fox et al., 2011a, b), and risk of transitioning from non-frail to frail is 73% (Jamsen et al., 2016). Increased levels of exposure to anticholinergic drugs are correlated with dementia (p = .05 to < .001)(Campbell et al., 2010; Fox et al., 2011a, b; Pfistermeister et al., 2017) and worsening Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (p < .001)(Gray et al., 2015). An interaction was found between ApoE4 carriers and anticholinergic medications with users having the lowest cognitive scores. Irrespective of ApoE4 status, drugs with high anticholinergic properties were associated with cognitive and physical decline (Jamsen et al., 2016; Kolanowski et al., 2015; Lanctot et al., 2014; Risacher et al., 2016; Uusvaara et al., 2009). Methods for measuring medication burden varied significantly between studies making it difficult compare study results. Thus, further research is need to understand ACB-associated cognitive impairment in frail older adults and how this issue might be managed (Salahudeen and Nishtala, 2016).

3.3. Inflammatory/Immunity markers

There were twenty neuroinflammatory markers are associated with both cognitive impairment and physical frailty. These included: elevated levels of IL6, C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha), uric acid, IL1-beta, IL1-alpha, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), cortisol/dehydroepiandrosterone ratio, IL1RA, CD4, CD8, IL6R, IL-18, TNF-a receptor I (TNFR1), cortisol, homocysteine, fibrinogen, Intercellular Adhesive Molecule-1 (ICAM-1), circulating osteogenic progenitor (COP) cells, and beta 2-microglobulin (B2M). Neuroinflammatory markers IL-6, TNF-alpha, and CRP were found to be elevated in older adults with sarcopenia. ICAM-1 was found to be elevated for both cognitive impairment and physical frailty (Lee et al., 2016; O’Bryant and Waring, 2010). Studies have shown ICAM-1 to be associated with enhanced production of IL-6, TNF-alpha suggesting that it activates a pro-inflammatory cascade (McCabe et al., 1993). ICAM-1 is associated with vascular inflammatory processes related to atherosclerosis, cerebral small vessel disease (Rouhl et al., 2012). The presence of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hormones such as dehydroepiandrosterone can interact with inflammatory markers to influence disease. Additionally, all the neuroinflammatory markers associated with cognitive frailty were associated with either cognitive impairment or physical frailty. These neuroinflammatory cytokines were found to be associated with cognitive impairment and frailty in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggesting that these markers could be both early and persistent markers. This relationship should be explored further with clinical markers such as gender and body mass index (Gale et al., 2013).

3.4. Laboratory markers

Twenty laboratory markers are associated with both phenotypes and include: Nutritional markers: low levels of vitamin D, total albumin, and selenium; cardiovascular/endocrine markers: elevated total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, insulin like growth factor protein (IGF-1), glucose, insulin resistance, HbA1c; Hematology/renal markers: elevated creatinine, creatinine clearance, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), white blood cells (WBC); and decreased hemoglobin, hematocrit, cobalamin deficiency (B12), and increased methylmalonic acid (MMA), and low levels of total testosterone associated with decreased lean muscle mass and cognitive impairment. These markers combined with endocrine and immune markers suggest changes to the cellular immune system and HPA axis that are related to cognitive and physical decline. Additionally, several studies included these markers and the inflammatory/immune markers as a composite score and found an increased risk for developing cognitive impairment, frailty, and mortality (Baylis et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2015; Gruenewald et al., 2009; Heringa et al., 2014; Kobrosly et al., 2012; O’Bryant and Xiao, 2010).

3.5. Protein markers

Several of the protein markers were measured by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and included known biomarkers associated with the neurofibrillary tangles involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia (Mattsson et al., 2013). None of these markers (i.e. p-tau, Apeta-42) have been studied in frailty. Two markers measured by serum/plasma were associated with both cognitive impairment and frailty, these included: sirtuin 1 and cystatin C. The down regulation of Sirtuin 1 has been reported to be involved in the pathway that controls the expression of Apeta peptide through ADAM10 (Kumar et al., 2013). Concentrations of sirtuin 1 decline with age but the decline was found to be more significant in individuals with cognitive impairment and frailty compared to age matched healthy individuals (Kumar et al., 2013, 2014). Additionally, cystatin C has been thought to bind to soluble Apeta preventing accumulation in the brain (Sundelof et al., 2008). Decreased serum cystatin C has been associated with higher risk for cognitive impairment and gait speed decline(Liu et al., 2014; Yaffe et al., 2008).

3.6. Metabolomics and oxidative stress markers

No metabolomics markers were found to be related to cognitive frailty. Two oxidative stress markers were associated, these included: malondialdehyde (MDA) and protein carbonyls. MDA and protein carbonyls are well established oxidative biomarkers and are considered to be a good measure of systemic oxidative stress (Inglés et al., 2014). Both are associated with frailty and cognitive impairment however, do not predict the development or progression of disease (Baldeiras et al., 2010; Inglés et al., 2014).

3.7. Genomic markers

The Supplementary Appendix Table C shows a complete list of genetic markers identified by phenotype. Six genes were found to be associated with cognitive impairment, physical frailty, and sarcopenia in candidate gene studies: IL6 rs1800796, TNF rs1800629, IL-18 rs360722, IL1-beta rs16944, and COMT with different SNPs, rs4680 for cognitive decline and rs4646316 for frailty. IL6 and TNF, IL-18, ILl-beta have corresponding serum markers that are associated with both phenotypes (see inflammatory/immunity markers) (Baune et al., 2008; Dixon et al., 2014; Mekli et al., 2016; Patel et al., 2014). There are 13 serum biomarker and gene correlations, these are shown in Table 4. Further evaluation is needed to determine clinical relevance and if there is a direct correlation between gene expression and serum marker function.

Table 4.

Serum and gene correlations by phenotype Genetic.

| Serum biomarker | Phenotype associated with serum biomarker |

Genetic biomarker | Phenotype associated with genetic biomarker |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D (25(OH)D) | Frailty and cognitive decline | VDR (Vitamin D receptor) | Sarcopenia |

| Cystatin C | Frailty and cognitive decline | CST3 (cystatin) | Cognitive decline |

| Chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) | Cognitive decline | CCL2 | Cognitive decline |

| Myostatin | Frailty | MSTN (myostatin) | Sarcopenia |

| Klotho | Frailty | KLOTHO | Cognitive function |

| IL-6 | Frailty and cognitive decline | IL-6 | Sarcopenia and cognitive decline |

| TNF-alpha | Frailty and cognitive decline | TNF-alpha | Sarcopenia, frailty, and cognitive decline |

| IL-6R | Frailty and cognitive decline | IL-6R | Cognitive decline |

| CRP | Frailty and cognitive decline | AP2A2 (trait CRP), USP50 (trait CRP) | Cognitive decline |

| IL-1βeta | Frailty and cognitive decline | IL-1βeta | Cognitive decline |

| IL-18 | Frailty | IL-18 | Frailty |

| IL-12p70 | Cognitive decline | IL-12A | Frailty |

| Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | Cognitive decline | BDNFval66Met | Cognitive decline |

Note: see Supplementary Appendix Table C for full list of genes and references.

4. Discussion

It has previously been postulated that a dysregulation across multiple systems may be the potential cause for both cognitive impairment and frailty (Cohen et al., 2015; Gruenewald et al., 2009; Kobrosly et al., 2012). The results from this systematic review provide biological plausibility for the novel cognitive frailty construct. The potential in identifying a unique biomarker that is the key to a specific molecular or cellular event is enticing but considering the complexity and individual variability to aging we need to consider the possibility that these interactions are non-linear. Several studies presented here have taken various approaches to combining biomarkers using methods such as allostatic load index, physiologic dysfunction scores, principle components analysis (PCA), and serum protein based algorithms (random forest methods) to yield a more accurate understanding in the relationship between biomarkers and detection of disease (Cohen et al., 2015; Gruenewald et al., 2009; Kobrosly et al., 2012; O’Bryant and Xiao, 2010). Of important note, are the findings of shared pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-18, and IL-1-beta) and associated genetic variants that influenced the production of circulating proteins for both physical frailty and cognitive decline. Specifically, IL6 rs1800796, TNF rs1800629, IL-18 rs360722, and IL1-beta rs16944 suggesting that they are clinically relevant SNPs. Chronic inflammation provides a basic mechanism for a shared pathogenesis of cognitive impairment and physical frailty. The concept of “inflammaging” (Franceschi et al., 2018) may provide a clinical and research framework to explore low-grade chronic inflammatory markers associated with vascular inflammatory processes related to atherosclerosis and cerebral small vessel disease leading cognitive frailty. Co-founding psychosocial and behavioral findings include depression and low health knowledge/ self-efficacy which decrease physiological reserves causing a decline in the ability to maintain allostasis leading to increased vulnerability to cognitive frailty.

Further defining the putative biomarkers related to cognitive frailty will lead to a better understanding of the interrelated neuropathology between physical frailty and cognitive impairment and, ultimately, to the development of targeted interventions focused on the prevention of cognitive and functional disabilities. Future research should focus on using systems biology approaches such as allostatic load index or boosted trees models which can include multiple markers of disease to build an accurate prediction model for the detection of cognitive impairment, frailty, and cognitive frailty. Integrating multiple biomarkers has the potential to help us better understand the complex physiological interactions of aging diseases. Such validated models for disease detection would be invaluable in the early detection and prevention of diseases unique to aging.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Frailty biomarkers by category

| Inflammatory/Immunity Markers | Laboratory Markers | Protein Markers | Metabolomics Markers | Oxidative Stress Markers | Clinical Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL6 | Vitamin D | Propeptide of type I procollagen (PINP) | X12063 | Serum 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) | Cardiovascular disease |

| C-reactive protein | Albumin | C-terminal telopeptide of type-1 collagen(Beta CTX) | Urate | Protein carbonyls | Increase Waist Circ/Waist-to-hip |

| Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) | Composite Score (multiple markers) | Extracellular heat shock protein (eHsp) 72 | Mannose | thol level (TTL) | Calibrated Protein intake |

| Uric Acid | Lipids: Total Cholesterol | Cystatin C | Myostatin | Derivate of reactive oxygen metabolites (d-ROM) | Increased falls |

| Fibrinogen | Insulin like growth factor protein (IGF-1) | Cytomegalovirus | Malondialdehyde (MDA) | Alcohol intake | |

| ILlbeta | Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | C-terminal Agrin Fragment (CAF) | Body Mass Index | ||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | White blood cells (WBC) | Sirtuin 1 | > 2 chronic diseases | ||

| Cortisol/Dehydroepiandrosterone ratio | Insulin resistance (IR-HOMA) | Sirtuin 2 | Anticholinergic medications | ||

| IL1RA | Creatinine | Sirtuin 3 | |||

| Motif chemokine 10/ Interferon-gamma (CXCL-10/IFN-gama) | Glycohemoglobin (HbAlc) | Complement component protein (Clq) | |||

| CD8 | Hemoglobin | Klotho | |||

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) | Lymphocytes | Lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP) | |||

| IL2 | Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) | ||||

| IL18 | Methylmalonic acid (MMA) | ||||

| TNF-a receptor I (TNFR1) | Carotenoids | ||||

| IL6R | Cobalamin deficiency (B12) | ||||

| Cortisol | Lipids: Triglycerides | ||||

| Homocysteine | Neutrophils | ||||

| Beta 2-microglobulin (B2M) | Follistatin | ||||

| Urine albumin-creatinine ratio | |||||

| Vitamin A | |||||

| Vitamin B1 | |||||

| Vitamin B6 | |||||

| Phosphorus | |||||

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2018.08.001.

References

- Baldeiras Inês, et al. , 2010. Oxidative damage and progression to Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 21 (4), 1165–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baune BT, et al. , 2008. Association between genetic variants of IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNF-alpha cytokines and cognitive performance in the elderly general population of the MEMO-study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33 (1), 68–76. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0306453007002181/1-s2.0-S0306453007002181-main.pdf?_tid =7025a50e-2374-11e6-929f-00000aab0f27&acdnat=1464289548_814235489927b21aa76601c0091b438c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis D, et al. , 2013. Immune-endocrine biomarkers as predictors of frailty and mortality: a 10-year longitudinal study in community-dwelling older people. Age 35 (3), 963–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biomarkers Definitions Working Group, 2001. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 69 (3), 89–95. 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. (June 6, 2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Yaffee K, Liverman C, 2015. Cognitive aging: progress in understanding and opportunities for action - PubMed - NCBI. Inst. Med. Natl. Acad. 1–331. (13 September 2015). http://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.library.vcu.edu/pubmed?term=cognitiveagingprocessinunderstandingopportunitiesforaction&cmd=correctspelling. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Patrick J., et al. , 2014. Frailty and depression in older adults: a high-risk clinical population. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 22 (11), 1083–1095. (March 26, 2018). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23973252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman AS, Bennett DA, 2013. Cognitive frailty. J. Nutr. Health Aging 17 (9), 738–739. (February 7, 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4070505&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman Aron S., et al. , 2014. Brain pathology contributes to simultaneous change in physical frailty and cognition in old age. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69 (12), 1536–1544. (16 December 2014). http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/content/69/12/1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NL, et al. , 2010. Use of anticholinergics and the risk of cognitive impairment in an African American population. Neurology 75 (2), 152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Alan A., et al. , 2015. Detection of a novel, integrative aging process suggests complex physiological integration. PLoS One 10 (3), 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2016. Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at. (1 May 2016). www.covidence.org.

- Dixon Roger A., et al. , 2014. APOE and COMT polymorphisms are complementary biomarkers of status, stability, and transitions in normal aging and early mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6 (SEP), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Zin Nyunt MS, Gao Q, Feng L, Yap KB, Ng T-P, 2017. Cognitive frailty and adverse health outcomes: findings from the Singapore longitudinal ageing studies (SLAS). J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18 (3), 252–258. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID, et al. , 2011a. Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59 (8), 1477–1483. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03491.x/asset/j.1532-5415.2011.03491.x.pdf?v=1&t=iooifg7c&s=72a855a07a9cad57d63184e4b8116a4e0a7e47c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Chris, Richardson Kathryn, Maidment ID., et al. , 2011b. Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59 (8), 1477–1483. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=2011252139& site=ehost-live. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Chris, et al. , 2014. Effect of medications with anti-cholinergic properties on cognitive function, delirium, physical function and mortality: a systematic review. Age Ageing 43 (5), 604–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi Claudio, et al. , 2018. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol (31 July2018). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30046148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, et al. , 2001. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56 (3), M146–M156. (27 August 2014). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11253156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, et al. , 2004. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.59 (3), M255–M263. (27 January 2015). http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/content/59/3/M255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale Catharine R., Baylis Daniel, Cooper Cyrus, Sayer Avan Aihie, 2013. Inflammatory markers and incident frailty in men and women: the english longitudinal study of ageing. Age 35 (6), 2493–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Health and Aging. (accessed 8 February 2015). https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/global-aging-accessed 8 February.

- Gray Shelly L., et al. , 2013. Frailty and incident dementia. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 68 (9), 1083–1090. (5 February 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3738027&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, et al. , 2015. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia. JAMA Intern. Med. 175 (3), 401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald Tara L., Seeman Teresa E., Karlamangla Arun S., Sarkisian Catherine A., 2009. Allostatic load and frailty in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57 (9), 1525–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Eun Sook, Lee Yunhwan, Kim Jinhee, 2014. Association of cognitive impairment with frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. IPA 26 (1), 155–163. (13 September 2015). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24153029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heringa SM, et al. , 2014. Markers of low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction are related to reduced information processing speed and executive functioning in an older population—the Hoorn study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 40 (1), 108–118. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglés Marta, et al. , 2014. Oxidative stress is related to frailty, not to age or sex, in a geriatric population: lipid and protein oxidation as biomarkers of frailty. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 62 (7), 1324–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamsen Kris M., et al. , 2016. Effects of changes in number of medications and drug burden index exposure on transitions between Frailty States and death: the concord health and ageing in men project cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64 (1), 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A.F Jansen., Jacobus R.B.J Brouwers., 2012. Clinical pharmacology in old persons. Scientifica 2012, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kelaiditi E, et al. , 2013. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./ I.A.G.G.) International Consensus Group. J. Nutr. Health Aging 17 (9), 726–734. (19 January 2015). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24154642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrosly RW, Seplaki CL, Jones CM, van Wijngaarden E, 2012. Physiologic dysfunction scores and cognitive function test performance in US adults. Psychosom. Med. 74 (1), 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski Ann, et al. , 2015. Anticholinergic exposure during rehabilitation: cognitive and physical function outcomes in patients with delirium superimposed on dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 23 (12), 1250–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Rahul, et al. , 2013. Sirtuin1: a promising serum protein marker for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8 (4), 4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Mohan N, Upadhyay AD, et al. , 2014. Identification of serum sirtuins as novel noninvasive protein markers for frailty. Aging Cell 13 (6), 975–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt Krista L., et al. , 2014. Original research reports assessing cognitive effects of anticholinergic medications in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosomatics 55 (1), 61–68. 10.1016/j.psym.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Wei-Ju, et al. , 2016. Soluble ICAM-1, independent of IL-6, is associated with prevalent frailty in community-dwelling elderly taiwanese people. PLoS One 11 (6), e0157877 (25 July 2018). http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lista I, Sorrentino G, 2010. Biological mechanisms of physical activity in preventing cognitive decline. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 30 (4), 493–503. (23 July 2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20041290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Christine K., et al. , 2014. Chronic kidney disease defined by cystatin C predicts mobility disability and changes in gait speed: the framingham offspring study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69 (A(3)), 301–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N, et al. , 2013. CSF protein biomarkers predicting longitudinal reduction of CSF β-amyloid42 in cognitively healthy elders. Transl. Psychiatry 3 (8), e293 10.1038/tp.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux Richard., 2004. Biomarkers: potential uses and limitations. NeuroRx 1 (2), 182–188. (6 June 2017). http://link.springer.com/10.1602/neurorx.1.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SM, et al. , 1993. SICAM-1 enhances cytokine production stimulated by alloantigen. Cell. Immunol. 150 (2), 364–375. (31 July 2018). http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0008874983712049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekli Krisztina, et al. , 2016. Proinflammatory genotype is associated with the frailty phenotype in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 28 (3), 413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishtala Prasad S., Salahudeen Saji, Mohammed Sarah, Hilmer N, 2016. Anticholinergics: theoretical and clinical overview. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 15 (6), 753–768. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26966981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryant Sid E., Waring Stephen C., et al. , 2010. Decreased C-reactive protein levels in Alzheimer disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 23 (1), 49–53. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0891988709351832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryant Sid E., Xiao Guanghua, et al. , 2010. A serum protein-based algorithm for the detection of alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 67 (9), 1077–1081. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20837851%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC3069805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group, 2011. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; (7 February 2015). http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. [Google Scholar]

- Panza Francesco, et al. , 2006. Cognitive frailty: predementia syndrome and vascular risk factors. Neurobiol. Aging 27 (7), 933–940. (15 October 2015). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16023766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel Harnish P., et al. , 2014. Lean mass, muscle strength and gene expression in community dwelling older men: findings from the Hertfordshire Sarcopenia Study (HSS). Calcif. Tissue Int. 95 (4), 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfistermeister Barbara, et al. , 2017. Anticholinergic burden and cognitive function in a large German cohort of hospitalized geriatric patients. PLoS One 12 (2), e0171353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Wendy Wei, et al. , 2014. angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and Alzheimer disease in the presence of the apolipoprotein E4 allele. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 22 (2), 177–185. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1064748112000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripley Brian, Venables Bill, Bates Douglas, Hornik David, Kurt Gebhardt, Albrecht Firth, 2017. Package ‘MASS. (21 June 2017). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MASS/MASS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Risacher Shannon L., et al. , 2016. Association between anticholinergic medication use and cognition, brain metabolism, and brain atrophy in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Neurol. 332 (7539), 455–459. http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhl, Rob PW., et al. , 2012. Vascular inflammation in cerebral small vessel disease. Neurobiol. Aging 33 (8), 1800–1806. (31 July 2018). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21601314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahudeen Mohammed Saji, Nishtala Prasad S., 2016. Examination and estimation of anticholinergic burden: current trends and implications for future research. Drugs Aging 33 (5), 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer Larissa, et al. , 2015. Preferred Reporting items for systematic review and metaanalysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 349, g7647 (June 6, 2017). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25555855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solfrizzi Vincenzo, et al. , 2017. Reversible cognitive frailty, dementia, and all-cause mortality. The Italian longitudinal study on aging. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 18 (1) 89.e1–89.e8. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S152586101630490X (30 July 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundelof J, et al. , 2008. Serum cystatin C and the risk of Alzheimer disease in elderly men. Neurology 71 (14), 1072–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibeau Sherilyn, Peggy McFall, G., Camicioli Richard, Dixon Roger A., 2017. Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers interactively influence physical activity, mobility, and cognition associations in a non-demented aging population. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 60 (1), 69–86. (25 July 2018). http://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-170130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusvaara J, et al. , 2009. Association between anticholinergic drugs and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele and poorer cognitive function in older cardiovascular patients: a crosssectional study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57 (3), 427–431. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02129.x/asset/j.1532-5415.2008.02129.x.pdf?v=1&t=iooigi5m&s=65d42b8c991f50d67f9704d9ef299c6fd2a89d40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, 2013. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and the risk of dementia. J. Gerontol. Ser. A: Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 68 (4), 412–418. (26 March 2018). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22987797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese Joe, et al. , 2014. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: multicountry prevalence and dementia risk. Neurology 83 (8), 718–726. (26 March 2018). http://www.neurology.org/cgi/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham Hadley, Chang Winston, 2017. Package ‘Ggplot2. (21 June 2017). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/ggplot2.pdf.

- Yaffe Kristine, et al. , 2008. Cystatin C as a marker of cognitive function in elders: findings from the health ABC study. Ann. Neurol. 63 (6), 798–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.