Abstract

Social relations are part of the complex set of factors affecting health and well-being in old age. This systematic review seeks to uncover whether social interventions have an effect on social and health-related measures among nursing home residents. The authors screened PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO for relevant peer-reviewed literature. Interventions were included if (1) they focused primarily on social relations or related terms such as loneliness, social support, social isolation, social network, or being involuntarily alone either as the base theory of the intervention or as an outcome measure of the intervention; (2) they were implemented at nursing homes (or similar setting); (3) they had a narrative activity as its core (as opposed to dancing, gardening or other physical activity); (4) their participants met either physically or nonphysically, ie, via video-conference or the like; and if (5) they targeted residents at a nursing home. The authors systematically appraised the quality of the final selection of studies using the Mixed Methods Assessments Tool (MMAT) version 2011 and did a qualitative synthesis of the final study selection. A total of 10 studies were included. Reminiscence therapy was the most common intervention. Studies also included video-conference, cognitive, and support group interventions. All studies found the social interventions brought about positive trends on either/or the social and health-related measures included. Despite limited and very diverse evidence, our systematic review indicated a positive social and health-related potential of social interventions for older people living in nursing homes or similar institutions.

Keywords: social relations, social support, loneliness, social isolation, nursing homes, older people, interventions, social interventions, outcome assessment

What do we already know about this topic?

Social relations shape health among older adults and nursing homes constitute an unexplored setting for social interventions aimed at strengthening social relations and related social concepts such as social support, loneliness, and social isolation as well as health-related measures.

How does your research contribute to the field?

We found that a limited number of studies explore effects of social interventions and they use different study designs, intervention designs/activities, and outcome measures.

What are you research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

We find a trend toward a positive effect of social interventions on social and health-related outcome measures and suggest that more research is needed to explore this potential more thoroughly.

Introduction

Health and well-being in old age are shaped by unique and individual aging processes, which are again influenced by a range of social and structural factors that are present throughout the life course.1 In this systematic review, we focus on the social aspects such as social relations which, together with their negative manifestations such as loneliness and social isolation, are part of this complex set of factors shaping health in old age.2,3 Social relations are often defined by the structure of an individual’s social life (network size, diversity, and contact frequency), by the functions of these elements of social life (ie, in providing emotional and instrumental support) and by various stressors (conflicts, demands, worries, disappointments) caused, in turn, by these social relations. Relational stress and strain may be caused by experiencing conflicts and excessive demands from the individual’s social relations.4,5 A perceived discrepancy between desired social relations and actual social relations might cause the subjective, unpleasant feeling of loneliness. Loneliness is a feeling that may arise when surrounded by other people as well as when alone and missing social contact. It is therefore relevant to distinguish between social isolation (being alone) and loneliness as a subjective undesired feeling (being involuntarily alone). There is, however, evidence pointing toward a close link between subjective social isolation and loneliness; individuals who perceive themselves as socially isolated have an increased risk of experiencing loneliness, and individuals who experience loneliness more often feel socially isolated than individuals who do not.2,6,7 Across countries, the causes of loneliness among older people seem to be complex and multifactorial with studies pointing toward a negative effect of weak or straining social relations, poor health and disease status, and socioeconomic factors such as low income and unemployment.4

Studies have shown that people with weak or straining social relations have higher morbidity and mortality than people with strong social relations.4,5,8 Similarly, loneliness has been found to negatively affect both physical and mental health.2,9,10 Studies find that loneliness is associated with morbidity in terms of cardiovascular diseases, increased inflammatory response, changes to the immune system, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression.2,10 Loneliness has also been suggested to cause emotional changes which activate neurobiological and behavioral changes, thereby affecting various health outcomes through, for instance, a lowered level of physical activity.2 Loneliness has also been found to be directly related to an increased use of health care services, with findings suggesting that at the same level of objective need for health care, individuals feeling lonely are more likely to contact their general practitioner than individuals who are not feeling lonely.11

Throughout life, losses of close relations and disruptions to one’s social networks are likely to occur. As needs and resources change, the structure and function of one’s social relations and the experience of relational strain may change as well: These are not static phenomena, but rather may be specific to different phases of life. Moreover, a range of events throughout one’s life influence the risk of experiencing loneliness as a potentially negative aspect of lacking social relations: for instance, living alone, losing a spouse, or being diagnosed with a disease; or moving to a new place such as a nursing home.2 Disease and functional decline may furthermore shape the experience of social relations and social support in old age. In the Nordic countries, those moving into nursing homes generally exhibit greater vulnerability in terms of physical and cognitive functioning and appear to have less of a social network than older people living at home.12 Loneliness seems to be closely linked to dementia and both loneliness and dementia have been found to be particularly prevalent among residents at long-term care homes and nursing homes/among institutionalized older people.13,14 People with dementia have been found to be at risk of experiencing loneliness which is possibly due to the diminishing ability to communicate caused by the disease.15

This systematic review primarily seeks to uncover the existing evidence of the effects of social interventions on social measures among nursing home residents. As a secondary aim, it seeks to uncover possible effects of these interventions on health-related measures.

Methods

Search Strategy

We conducted searches in PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO during December 2017 based on keywords generated from the overall domains of social relations, intervention, aging, and nursing home. MeSH term searches were constructed in PubMed to identify relevant synonyms. See Appendix A for a detailed description of the search strategy and generation of key words. Articles in English, Danish, Swedish or Norwegian were included and there were no restriction on inclusion date meaning that all articles published up until December 2017 were considered for inclusion. All 4 researchers independently screened all of the titles, abstracts, and full-texts for eligibility. In many cases, the first decision on whether to exclude or include an article was based on a title screen, and next on an abstract screen before full-text versions were obtained.

Selection Criteria

Eligible studies were those addressing interventions

focusing primarily on social relations or related terms such as loneliness, social support, social isolation, social network or being involuntarily alone either as the base theory of the intervention or as an outcome measure of the intervention

implemented at nursing homes (or similar setting)

having a narrative activity as its core (as opposed to dancing, gardening or other physical activity)

where participants met either physically or nonphysically, ie, via video-conference or the like

aimed at residents at nursing homes as opposed to a focus on employees or relatives

All types of study designs and all types of health-related measures were considered for inclusion as this was a secondary aim of the systematic review. The term outcome measure is used when addressing measurements made on a range of social and health-related factors before, during, and after the intervention.

Quality Assessment Tool

We used the Mixed Methods Assessments Tool (MMAT) version 2011 to appraise the quality of the studies.16 This instrument has proven useful in other mixed-methods systematic reviews encompassing a transparent and comparable approach to appraise studies with different designs.17 The primary researcher did the initial quality assessment independently and then discussed it in detail with the 3 coauthors.

Data Extraction

The primary researcher independently extracted the data into customized data sheets developed by all authors. Data were extracted on core activity of the intervention (ie, reminiscence therapy, video-conference program, cognitive intervention, support group intervention), the objective of the study, mean age of participants, setting, measures included reported in the studies and reported intervention effects. All authors crossed-checked the data extraction giving their feedback, and data were qualitatively synthesized. Variables extracted are shown in Table 2. For the quality appraisal, sources of study data, process for analyses and description of context, randomization, allocation concealment, blinding, level of outcome data, dropout rate, and recruitment processes were extracted and reported in Table 1.

Table 2.

Baseline Study Characteristics.

| Authors, country and year of publication | Activity | Objective(s) | Participants | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chao et al., Taiwan, 2006 | Reminiscence therapy | To describe the effect of participation in reminiscence group therapy on older nursing home residents’ depression, self-esteem and life satisfaction | Nursing home residents | GDS-S (Geriatric Depressive Scale-Short Edition), Rosenberg Self-esteem Survey (RSE), Life satisfaction is the participants’ subjective response to their lives and surroundings as measured by the Quality of Life Index (QLI) |

| Chiang et al., Taiwan, 2009 | Reminiscence therapy | To examine the effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological well-being, depression, and loneliness among institutionalised elderly people | Nursing home residents | Center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D), Symptoms checklist-90-R (psychological well-being), Revised University of California Los Angeles loneliness scale (RULS-V3), Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) (cognitive screening measurement) |

| Haslam et al., UK, 2010 | Reminiscence therapy | To provide a theory-driven evaluation of reminiscence based on a social identity framework. This framework predicts better health outcomes for group-based interventions as a result of their capacity to create a sense of shared social identification among participants | Residents in standardised and specialised care units | Cognitive performance (Addenbrookes cognitive examination – revisited (ACE-R)), well-being (Hospitality Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Quality of Life in Alzheimers Disease Scale (QoL-AD), Life Improvement scale, Quality of Life Change scale), identity (Personal identity strength, social group homogeneity) |

| Karimi et al., Iran, 2010 | Reminiscence therapy | To examine the therapeutic effectiveness of integrative and instrumental types of reminiscence for the treatment of depression in institutionalised older adults dwelling in a nursing home | Nursing home residents | GDS-15 to measure depression, MMSE to measure cognitive performance |

| Serrani Azcurra, Argentina, 2012 | Reminiscence therapy | To investigate whether a specific reminiscence programme is associated with higher levels of quality of life in nursing homes residents with dementia | Nursing home residents with dementia | The Social Engagement Scale (SES) and Self Reported Quality of Life Scale (SRQoL) |

| Stinson et al., USA, 2005 | Reminiscence therapy | To assess the effect of group reminiscence on depression and self-transcendence of older women residing in an assisted living facility. One objective was to determine if depression decreased in older women after structured reminiscence group sessions held twice-weekly for a six-week period. A second objective was to determine if self-transcendence increased after structured reminiscence group sessions held twice-weekly for a six-week period | Residents at assisted living facilities, women | Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Self-Transcendence Scale (STS) |

| Tsai et al., Taiwan, 2010 | Video-conference programme | To evaluate the effectiveness of a video-conference intervention programme in improving nursing home residents’ social support, loneliness and depressive status | Nursing home residents | Social Supportive Behavior Scale, University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale, and Geriatric Depression Scale |

| Winningham et al., US, 2008 | Cognitive intervention | To assess the effectiveness of a cognitive intervention on residents’ levels of social support and loneliness | Residents at assisted living facilities | Social Support Appraisal (SS-A), Social Support Behaviors (SS-B), UCLA Loneliness Scale) |

| Theurer et al., Canada, 2014 | Support group intervention | To present a rationale for and describe a new intervention involving mutual support groups in Long Term Care Homes (LTCH); evaluate its process, structure, and content; and provide evidence that supports refinement and replication | Residents and staff at long term care homes | No predeveloped measures, but themes identified based on interviews with residents and staff: building relationships, helping one another, sharing fears and burdens, and having a say |

| Gudex et al., Denmark, 2010 | Reminiscence therapy | To investigate the consequences for nursing home residents and staff of integrating reminiscence into daily nursing care | Nursing home residents | Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI), Alzheimers Disease Related Quality of Life (ADRQL), Gottfries-Bråne-Steen scale (GBS) to measure the general functioning of people with dementia, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Severe Impairment Battery – short form (SIB-S), Maslach Burnout inventory – Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), Satisfaction with Nursing Care and Work Assessment (SNCW), Short Form-12v2 measuring self-assessed health status |

Table 1.

Assessment of Methodological Quality According to the McGill Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

| Study design | Appraisal score |

|---|---|

| Qualitative | |

| Theurer et al, Canada, 2014 | 75% (***) |

| Quantitative randomized | |

| Chiang et al, Taiwan, 2009 | 25% (*) |

| Haslam et al, the United Kingdom, 2010 | 25% (*) |

| Karimi et al, Iran, 2010 | 0% (.) |

| Serrani Azcurra, Argentina, 2012 | 75% (***) |

| Stinson et al, the United States, 2005 | 0% (.) |

| Gudex et al, Denmark, 2010 | 50% (**) |

| Quantitative nonrandomized | |

| Chao et al, Taiwan, 2006 | 100% (****) |

| Tsai et al, Taiwan, 2010 | 100% (****) |

| Winningham et al, the United States, 2008 | 75% (***) |

Results

Study Selection

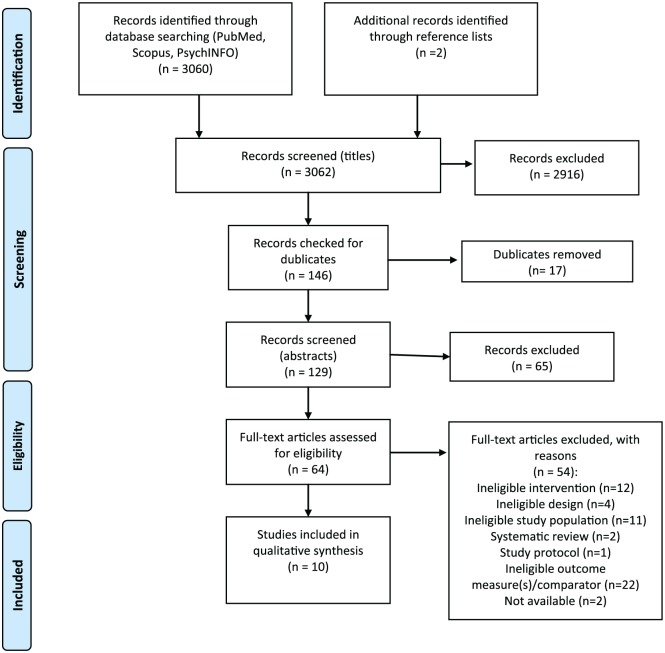

The selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1. A total of 3062 studies were identified in the initial searches in databases and through references lists. After removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened, producing a selection of 64 articles. These were given full-text assessment based on which 54 articles were excluded. The reasons for excluding studies based on the full-text reading was

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Source. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.20

not meeting the inclusion criteria for being an intervention of interest (ie, in cases where the intervention was animal assisted or centered around a nutrition or physical training activity),

inappropriate design (we found 2 studies where there were no actual intervention being assessed, and 1 which was a study protocol),

an irrelevant study population (ie, a disease specific group, focus only on employees or on residents and family), and

reporting on irrelevant outcome measures (agitation, affect, disruptive behavior).

We also excluded 2 systematic reviews because they did not meet the scope of this systematic review. One of these systematic reviews focused specifically on animal assisted therapy,18 and the other review addressed family interventions and not interventions aimed at relations between residents participating in the intervention as this is the focus of this systematic review.19 We did however go through the references but found none relevant for the scope of this systematic review.

Ten articles were finally included in the systematic review. The screening process resulted in a mixture of quasi-experimental studies, randomized controlled trials, quantitative experimental studies, and a mixed-methods qualitative study.

Quality Appraisal

In Table 1, a summary of the assessment of quality according to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) is presented. Overall, the included studies varied in quality. Two quantitative nonrandomized studies were given the highest score (100% (****)). One nonrandomized quantitative, 1 randomized quantitative, and 1 qualitative were given the second highest score (75%(***)). One quantitative randomized study scored 50% (**) and 2 quantitative randomized studies scored 25% (**). Two quantitative randomized studies did not meet any of the quality criteria. See Appendix B for a detailed description of the quality assessment.

Study Characteristics

The included studies varied in terms of geography, types of study design, intervention, and outcome measures. Three of the studies were from Taiwan, 2 from the United States, and the rest from Iran, Argentina, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Denmark. Seven of the studies addressed interventions based on reminiscence therapy, 1 addressed a video-conference intervention, 1 a cognitive intervention, and 1 a support group intervention. None of the studies reported specifically on social relations as an outcome measure. The outcome measures in the included studies and reported on in this systematic review were social support, depression, well-being, life satisfaction, loneliness, cognitive performance, identity, quality of life, social engagement, and self-transcendence. Six of the studies reported on interventions implemented in nursing homes, 1 from a standardized and specialized care institution, 2 from assisted living facility, and 1 from a long-term care home. In the end of this section, the results will be framed in light of these different settings, and it will be discussed further in the discussion. Table 2 presents the intervention characteristics in more detail.

The intervention effects are described in Table 3. Seven of the included studies assessed interventions with reminiscence therapy. Three of the studies reported a positive effect of reminiscence therapy on depressive measures21-23 out of which the study by Chao et al was assessed as being of high quality. However, the positive effect found by Chao et al was not significant, and 1 study assessed to be of low quality24 reported that reminiscence had no significant effect on depression. All of the studies reporting on depressive measures had a time perspective in their analyses—either with a baseline and follow-up design or with a pretest posttest design. Two studies of low quality assessed well-being22,25 and 1 found a positive effect22 and the other found no effect.25 Loneliness was only addressed in 1 of the studies where it was found to decrease right after reminiscence therapy and further after 3 months’ follow-up.22 However, the study was assessed to be of low quality. One study assessed to be of high quality measured life satisfaction and found a positive but not significant effect over time.21 Another high-quality study reported a positive effect on quality of life of group reminiscence therapy and a positive effect on social engagement.26 A study, albeit of low quality, found group reminiscence therapy to have a positive effect on cognitive performance and sense of identity.25 A study of medium quality assessing the effect on cognitive level, agitated behavior, and general functioning found no effect on either of these measures but reported that most staff in the intervention group considered reminiscence a useful tool that improved their communication with residents, and one that they would recommend to other nursing homes.27 One of the included studies, assessed to be of high quality, assessed a video-conference program intervention28 with the objective of evaluating the intervention effect on social support, loneliness, and depressive status. The experimental group received 5 min/week of video-conference interaction with their family members for 3 months, and the control group received regular care only. A trained research assistant helped the residents to use the video-conference technology. The authors found a significant decrease in depressive scores at 3 months after baseline, and they found that loneliness had decreased at both 1-week and 3-month follow-up. They also found a positive effect on social support measured on 2 subscales: appraisal and emotional social support.

Table 3.

Study Results.

| Authors, country and year of publication | N | Mean age (years) | Intervention effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chao et al, Taiwan, 2006 | 18 | 79.6 (experimental group), 76.9 (control group) | Levels of depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction all showed an improvement in the experimental group. Only the variable of self-esteem achieved a significant level of improvement (P = .001). In the control group, only the self-esteem variable showed improvement, but this was not statistically significant. |

| Chiang et al, Taiwan, 2009 | 92 | 77.4 (experimental group), 77.1 (control group) | Average depression score in the experimental group decreased from 19.11 points in the pretest to 16.18 and 15.49 points after intervention and 3 months follow-up, respectively. The difference of the depression status in the posttest and follow-up tests differed significantly between experimental and control groups (z = −7.09, P < .0001; z = −7.82, P < .0001). The average psychological well-being score fell from 27.09 points to 24.13 and 23.91 points in the experimental group right after reminiscence therapy and 3 months follow-up, and psychological well-being in the follow-up tests was significantly different between groups (z = − 10.25, P < .0001; z = −10.63, P < .0001). The average loneliness score declined from 42.24 points to 34.82 and 35 points in the experimental group right after reminiscence therapy and 3 months follow-up, indicating that the feeling of loneliness improved from moderate to mild. And likewise, the difference in the feeling of loneliness in the follow-up tests was significant between the groups (z = −27.26, P < .0001; z = −22.75, P < .0001). |

| Haslam et al, the United Kingdom, 2010 | 73 | Not reported | Cognitive performance: a significant main effect of treatment condition on the ACE-R, F(2, 71) = 7.29, P = .001, effect size r = .41. Post hoc analysis indicated that those who participated in group reminiscence (GR) showed a significant improvement in cognitive performance relative to those who either took part in individual reminiscence (IR) (P = .001) or played Skittles (GC; P = .005). Well-being: a significant main effect for experimental condition on this combined scale, F(2, 71) = 3.36, P = .04, effect size r = .29. Post hoc analysis indicated that playing Skittles (GC) led to significant improvements in well-being relative to participating in either GR (P = .03) or IR (P = .019). Identity: on the measure of social group homogeneity (ie, identification), there was a significant main effect for treatment condition, F(2, 71) = 3.02, P = .05, effect size r = .28. Post hoc analysis indicated that after the intervention, residents who had received IR experienced a reduction in identification relative to residents who received either GR (P = .03) or Skittles (group control (GC); P = .047). |

| Karimi et al, Iran, 2010 | 29 | 70.5 | Analysis of changes from pretest to posttest revealed that integrative reminiscence therapy led to statistically significant reduction in symptoms of depression in contrast with the control group (F = 27.095, P < .001). Although instrumental reminiscence therapy also reduced depressive symptoms, this improvement was not statistically significant compared with the control group (effect size and P value not reported). |

| Serrani Azcurra, Argentina, 2012 | 135 | 85.7 | Significant differences in the intervention group between baseline, 12 weeks and 6 months in the SES (effect size = 0.267), and for the SRQoL significant differences between 12 weeks and 6 months (effect size = 0.450). Logistic regression analyses showed that predictors of change in the SRQoL were associated with fewer baseline anxiety symptoms and depression scores. |

| Stinson et al, the United States, 2005 | 24 | 82.2 | There were no overall statistically significant differences in self-transcendence between the 2 groups (reminiscence vs activity) or across the 3 time periods (baseline, 3 and 6 weeks). However, there was a nonsignificant trend for the activity group to have lower self-transcendence scores than the reminiscence group. There were no overall statistical differences in depression between the 2 groups (reminiscence vs activity) or across the 3 time periods (baseline, 3 and 6 weeks). However, there was a trend for the reminiscence group to have lower depression scores than the activity group. |

| Tsai et al, Taiwan, 2010 | 57 | 74.4 (experimental group), 78.5 (control group) | For depressive status, the mean change in the GDS scores at 3 months after baseline was shown by generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis to be 1.4 points lower for the experimental group than for the control group, a significant difference (P = .02). For loneliness status, the change in the mean UCLA Loneliness Scale scores was significantly different in the experimental group from that of the control group at both 1 week (–1.21, P = .02) and 3 months (–2.84, P = .03). As for social support, the changes in mean appraisal and emotional social support scores in the experimental group were significantly different from those in the control group both at 1 week (0.42, 0.39; P < .01, P = .01) and 3 months (0.61, 0.68; P < .01, P < .01) after baseline. |

| Winningham et al, the United States, 2008 | 58 | 82.1 | The CEP group’s SS-A scores did not change over time, t(28) = 1.34; P = .19; however, the control group had a significant decrease in SS-A scores from Time 1 to Time 2, t(27) = 3.46; P < .002. The CEP group’s SS-B scores did not change over time: t(28) = 0.15; P = .88; however, the control group had a significant decrease in SS-B scores from Time 1 to Time 2: t(28) = 3.57; P = .001. The CEP group’s loneliness scores did not change over time: t(28) = 1.35; P = .19; however, the control group had a significant increase in loneliness scores from Time 1 to Time 2: t(28) = 1.96; P = .06. |

| Theurer et al, Canada, 2014 | 72 | Not reported (55.4% were 85 or older) | Resident reports and observations indicate positive benefits including a decrease in loneliness, the development of friendships, and increased coping skills, understanding, and support. Participating staff reported numerous benefits and described how the unique group structure fosters active participation of residents with moderate-severe cognitive impairment. |

| Gudex et al, Denmark, 2010 | 348 | 82.3 | Most staff in the intervention group considered reminiscence a useful tool that improved their communication with residents, and that they would recommend it to other nursing homes. There were no significant differences between residents in the intervention group and in the control group in cognitive level, agitated behavior, or general functioning. Residents in the intervention showed a significantly higher score at 6 months in a quality of life subscale but there was no significant difference at 12 months. |

Note. ACE-R = Addenbrookes Cognitive Examination–Revisited; SES = Social Engagement Scale; SRQoL = Self-Reported Quality of Life Scale; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; CEP = cognitive enhancement program; SS-A = Social Support Appraisal; SS-B = Social Support Behaviors.

A study of high quality assessed the effect of a cognitive intervention29 on social support and loneliness. The cognitive enhancement program (CEP) predicted that a group-based intervention would lead to better social support networks and decreased loneliness. The CEP groups attended 3 sessions per week in their assisted living community. The sessions were designed to educate participants about the brain and memory and stimulate memory and cognitive activity, focusing on making new memories and doing activities that required relatively high levels of attention. The authors found the intervention produced no direct effect on social appraisal, social behaviors, or loneliness: Participants in the intervention group demonstrated no change, remaining at the same level on all 3 measures. However, those who did not participate in the intervention were found to have experienced a decrease in perceived social support (appraisal and behaviors) and an increase in perceived loneliness.

Finally, a support group intervention was addressed in a qualitative mixed-methods approach applying focus groups, systematic observations of 6 resident groups, and individual interviews with residents and staff.30 This study was assessed to be of high quality. The intervention consisted of weekly discussion groups using themes chosen by the participants and theme-associated music, readings, and photographs. Staff were provided with a 1-day training session and supplied with a facilitator’s guide and a group manual. There were no predeveloped outcome measures as such, but themes—identified based on the interviews with residents and staff—were relationship-building, helping one another, sharing fears and burdens, and having a say. Based on resident reports and observations, the authors stated that among numerous benefits were less loneliness, the development of friendships, and increased coping skills, understanding, and support. The participating staff also described how the unique group structure fosters active participation of residents with moderate-severe cognitive impairment.

Setting

Six studies21-23,26-28 addressed interventions implemented specifically in nursing homes. All of them found a positive effect on health-related measures such as depressive symptoms, quality of life, and life satisfaction, and 3 found positive effects on social outcomes measured by social support, social engagement, and loneliness.22,26,28 One study25 reported from an intervention implemented at a standardized and specialized care institution and found a positive effect on the health-related measure cognitive performance, but no effect on well-being. There was a positive effect on the sense of identity.25 Two studies24,29 addressed interventions implemented at assisted living facilities. One found positive effects on the social measures social support and loneliness29 and the other study found positive effects on depressive symptoms.24 One study30 addressed in an intervention implemented at a long-term care home and found positive effects on the social measures loneliness, social support, and developing friendships.

Discussion

This systematic review uncovered a body of evidence on whether and how social interventions have an effect on social and health-related measures among nursing home residents. Overall, the evidence-base was limited, with only 10 identified studies of varying quality. The identified studies described a range of different social interventions within the already wide field of social interventions for older adults, and the identified interventions furthermore took place in various settings in terms of cultural, social, and organizational characteristics. The different outcome measures and intervention designs made it difficult to draw one unified conclusion in terms of intervention effect. Most of the identified studies described interventions implementing reminiscence therapy as the core activity, whereas 1 described a support group intervention, 1 a cognitive intervention, and 1 a video-conference intervention. This illustrates how much the core activities of the interventions included in this systematic review differed from one another. Moreover, the implementation modes and time-perspectives in data collection (follow-up points) also varied between the studies, and altogether these differences might have affected the observed effectiveness of the included social interventions.

Methodology

This systematic review sought to uncover social interventions implemented at nursing homes and their possible effect on social and health-related measures. Because the main focus of this systematic review was on the inherent characters of social interventions, we were less selective with regard to the specific implementation setting and included outcome measures. It was however crucial, when screening and selecting studies for the systematic review, that the social interventions addressed had been implemented in an institutional setting constituting the participants homes (as opposed to at home or at an activity center). This implies that interventions implemented not only at nursing homes but also in other settings such as assisted living facilities and long-term care homes and at standardized and specialized care units were included in the systematic review. Residents in nursing homes, long-term care homes, and assisted living facilities might differ in terms of their social support networks, in and outside their institutional context, and in terms of physical and psychological health and well-being. For instance, it has been found in several studies that nursing home residents tend to have a high incidence of, eg, dementia.13 Hence, besides the cultural, social, and organizational differences in setting contexts, the population base were likely to differ as well. However, as reported in the Results section, we were not able to identify any differences in effects across settings.

In relation to methodological design of the included studies, the fact that we included all study designs in the systematic review, instead of restricting the search to include only experimental or randomized controlled trials, has according to Ogilvie et al strengthened the evidence synthesis.31 It would have been too restrictive to limit the literature search to experimental and/or randomized controlled trials because they have been found to exhibit difficulties in finding and reporting significant beneficial outcomes because of the complexity of the environment and resident population.32

The field of social interventions to strengthen social relations and social support among the oldest old living in nursing homes is heterogeneous. To ensure that relevant studies were captured during the search, screening, and reviewing processes, we included a rather broad range of social and health-related outcome measures as well as different types of social interventions. However, the common denominator of the included interventions was that they were centered around a social and/or narrative interaction between people—as opposed to interventions with pets or physical artifacts or activities such as playing videogames or dancing.

Adding to the complexity of this field, the countries in which the different studies have been implemented and assessed differ across a range of factors affecting health in old age such as living conditions throughout life, cultural attitudes toward health and health-related behaviors, and the structure and functioning of the social and health care sectors. All this might also account for some of the ambiguity in results found on intervention effects and should be considered when judging success of social interventions across different cultural settings. However, in spite of the described ambiguity of the results found in the reviewed studies, they did offer some trends and arguments which is why we now highlight and discuss the main implications.

Results

Regarding the social and health-related outcome measures included in the studies, all the studies demonstrated some positive effect among the participants in the intervention. Half the studies found significant positive results, while the other half found nonsignificant positive results. This, we find, indicates the positive potential of implementing social interventions among older people at nursing homes. However, larger and more unified studies in terms of study design, time perspective, and outcome measurements are needed if a more solid knowledge base is to be established. Moreover, as described in the results section, some of the studies found that the nursing home staff implementing the intervention also experienced benefits from the intervention such as improved communication with the residents. These findings point toward an additional need to focus on the staff involved when studying social interventions at nursing homes.

Another interesting argument found in some of the studies is that the group structure of the intervention—whether reminiscence therapy, support group, or video-conference—is an important element in creating positive results in social and health-related measures. The positive effect of social networks, and the support they might provide, is well-known in the literature and upholds the arguments found in this systematic review, that the group structure itself might be the key to sustain an activity beyond an intervention period and in building new social relationships.8,9

In this systematic review, the majority of the identified studies addressed interventions implementing reminiscence therapy demonstrating a rather diverse body of evidence for the effect on different social and health-related measures. Reminiscence therapy has been defined as the process of thinking or telling someone of past experiences that are personally significant and was originally developed specifically for use in dementia care in which it has been used for a long time.13 It may involve the discussion of past activities, events, and experiences with another person or group of people and is often assisted by aids such as videos, pictures, archives, and life story books.26 Reminiscence therapy might resemble approaches such as life review and life review therapy, but a distinction has been made in that reminiscence therapy is an unstructured autobiographical storytelling used to communicate with others, remembering past events and enhancing positive feelings. Life review, on the contrary, is more structured, covers the whole life span, and is often applied as a therapeutic approach.26 In support of reminiscence therapy among nursing home residents, a study from Australia addressing the effectiveness of specifically reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety, and depression in older adults in long-term care finds substantial evidence supporting that reminiscence is an effective treatment for depression. However, they find limited evidence supporting effective treatment of anxiety and loneliness, and in line with our discussions, they suggest further research including an improvement in methodological quality.33

Last, the results from a study focusing on the relationships with residents’ family members indicate it may be more feasible to strengthen existing close relationships, such as those with family members or old friends, than trying to establish new relationships, such as with other residents—regardless of the type of contact set in place (in person, telephone, video-conference).28

Conclusion

Consequently, we believe that this systematic review provides a useful overview of the current evidence on the effects of social interventions implemented among older people at nursing homes. We highlight a need for further studies in this field of applied gerontology. If researchers wish to establish a solid knowledge base to guide practitioners working with older people at nursing homes, it is clear that more research on social interventions at nursing homes is needed. Equally, if doing so, researchers need to choose carefully their measures of outcome so that results are comparable with existing evidence. Finally, an interesting element to add to future research would be to look into health economic aspects of implementing such social interventions in this specific population group.

Appendix

Appendix A.

Search Strategy.

| Social relations | AND | Intervention | AND | Aging | AND | Nursing home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support Interpersonal relation Interpersonal relations Psychology, social Social identity Social identities Sense of belonging Social isolation Loneliness Unwanted alone Social network Social networks Social interaction Social interactions |

Intervention Community intervention Community-based intervention Community based intervention Group-based intervention Group based intervention Implementation Social planning Psychosocial intervention Reminiscence therapy Peer support intervention Guideline Guidelines Intervention study Intervention studies Evaluation study Evaluation studies Multicomponent intervention Multicomponent interventions Social activity Social activities |

Ageing Aged Older adults Elder Elderly Older people Old age |

“Home for the aged” “Homes for the aged” “Old age home” “Old age homes” “Nursing home” “Nursing homes” “Assisted living facility” “Assisted living facilities” “Retirement home” “Retirement homes” “Old people’s home” “Old people’s homes” “Daily care” “24-hour care” “Care home” “Care homes” |

PubMed Search

((((“Social support” OR “Interpersonal relation” OR “Interpersonal relations” OR Psychology, social OR “Social identity” OR “Social identities” OR “Sense of belonging” OR “Social isolation” OR Loneliness OR “Unwanted alone” OR “Social network” OR “Social networks” OR “Social interaction” OR “Social interactions” )AND (Intervention OR “Community intervention” OR “Community-based intervention” OR “Community based intervention” OR “Group-based intervention” OR “Group based intervention” OR Implementation OR “Social planning” OR “Psychosocial intervention” OR “Reminiscence therapy” OR “Peer support intervention” OR Guideline OR Guidelines OR “Intervention study” OR “Intervention studies” OR “Evaluation study” OR “Evaluation studies” OR “Multicomponent intervention” OR “Multicomponent interventions” OR “Social activity” OR “Social activities”)) AND (Ageing OR Aged OR “Older adults” OR Elder OR Elderly OR “Older people” OR “Old age”)) AND (“Home for the aged” OR “Homes for the aged” OR “Old age home” OR “Old age homes” OR “Nursing home” OR “Nursing homes” OR “Assisted living facility” OR “Assisted living facilities” OR “Retirement home” OR “Retirement homes” OR “Old people’s home” OR “Old people’s homes” OR “Daily care” OR “24-hour care” OR “Care home” OR “Care homes”))

SCOPUS Search

“Social support” OR “Interpersonal relation” OR “Interpersonal relations” OR Psychology, social OR “Social identity” OR “Social identities” OR “Sense of belonging” OR “Social isolation” OR Loneliness OR “Unwanted alone” OR “Social network” OR “Social networks” OR “Social interaction” OR “Social interactions” AND Intervention OR “Community intervention” OR “Community-based intervention” OR “Community based intervention” OR “Group-based intervention” OR “Group based intervention” OR Implementation OR “Social planning” OR “Psychosocial intervention” OR “Reminiscence therapy” OR “Peer support intervention” OR Guideline OR Guidelines OR “Intervention study” OR “Intervention studies” OR “Evaluation study” OR “Evaluation studies” OR “Multicomponent intervention” OR “Multicomponent interventions” OR “Social activity” OR “Social activities” AND Ageing OR Aged OR “Older adults” OR Elder OR Elderly OR “Older people” OR “Old age” AND “Home for the aged” OR “Homes for the aged” OR “Old age home” OR “Old age homes” OR “Nursing home” OR “Nursing homes” OR “Assisted living facility” OR “Assisted living facilities” OR “Retirement home” OR “Retirement homes” OR “Old people’s home” OR “Old people’s homes” OR “Daily care” OR “24-hour care” OR “Care home” OR “Care homes”

PsycINFO Search

“Social support” OR “Interpersonal relation” OR “Interpersonal relations” OR Psychology, social OR “Social identity” OR “Social identities” OR “Sense of belonging” OR “Social isolation” OR Loneliness OR “Unwanted alone” OR “Social network” OR “Social networks” OR “Social interaction” OR “Social interactions” AND Intervention OR “Community intervention” OR “Community-based intervention” OR “Community based intervention” OR “Group-based intervention” OR “Group based intervention” OR Implementation OR “Social planning” OR “Psychosocial intervention” OR “Reminiscence therapy” OR “Peer support intervention” OR Guideline OR Guidelines OR “Intervention study” OR “Intervention studies” OR “Evaluation study” OR “Evaluation studies” OR “Multicomponent intervention” OR “Multicomponent interventions” OR “Social activity” OR “Social activities” AND Ageing OR Aged OR “Older adults” OR Elder OR Elderly OR “Older people” OR “Old age” AND “Home for the aged” OR “Homes for the aged” OR “Old age home” OR “Old age homes” OR “Nursing home” OR “Nursing homes” OR “Assisted living facility” OR “Assisted living facilities” OR “Retirement home” OR “Retirement homes” OR “Old people’s home” OR “Old people’s homes” OR “Daily care” OR “24-hour care” OR “Care home” OR “Care homes”

Appendix B.

MMAT Quality Assessment Details.Assessment of Methodological Quality According to the MMAT.

| Qualitative | 1.1 Are the sources of qualitative data relevant to address the research question? | 1.2 Is the process for analyzing data relevant to address the research question? | 1.3 Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to the context, eg, the setting, in which the data were collected? | 1.4 Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to researchers’ influence, eg, through their interactions with participants? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theurer et al, Canada, 2014 | Yes. The objective/research question is to evaluate the process, structure and content of the intervention. The sources of data are focus groups, individual interviews, and observations with residents and staff. | Yes. The analysis framework used has 5 stages: (1) listening to recordings, reading the transcripts, and observational notes; (2) identifying thematic framework; (3) Indexing; (4) charting (lifting quotes from original context and rearranging them under themes); (5) mapping and interpretation. The analysis also explored any variations of themes across the 2 facilities. | Insufficient information. A little is written about context on page 405: they state that when comparing the 3 homes, 2 characteristics stood out: prevalence of dementia differed, and level of participation in activities differed. | Yes. A self-reflexive process was used to identify any biases that the principal investigator held during the course of the study and its interpretations. In addition, validity checks of the data interpretations were conducted by the investigative teams. It is also addressed to a limited extent in the discussion p. 410. |

| Quantitative randomized | 2.1 Is there a clear description of the randomization (or an appropriate sequence generation)? | 2.2 Is there a clear description of the allocation concealment (or blinding when applicable)? | 2.3 Are there complete outcome data (80% or above)? | 2.4 Is there low withdrawal/dropout (below 20%)? |

| Chiang et al, Taiwan, 2009 | Yes. Those who consented to participate were randomly assigned to either control or experimental group by permuted block randomization. | No. No sufficient description and/or concealment not done and also no blinding of outcome, participants, or personnel. | No. Attrition/exclusion were reported (20 in the experimental group = 31% dropout rate, 18 in the control group = 28% dropout rate). | No. |

| Haslam et al, the United Kingdom, 2010 | No. They merely write that the study utilized a randomized controlled trial allocating participants to 1 of 3 interventions. | No. Not sufficient description and/or concealment not done. They state that facilitators were not (and could not be) blind to the condition to which participants had been assigned. | Yes. See flowchart in Figure 1, where it is shown that no one was excluded from analysis. | No. Total dropout rate was 37% (29% because of death, 8% because of withdrawal). |

| Karimi et al, Iran, 2010 | No. They merely write that 39 participants were randomly selected. They further describe that to form matched groups in terms of depression severity and gender, participants were systematically divided into 3 groups and were then randomly assigned to the 3 conditions of intervention (p. 882). But the randomization itself is not well described. | No clear description. | No clear description. | No. Total dropout rate was 25.6% (excluded for various reasons including suffering from an illness, not attending at least 60% of the sessions). |

| Serrani Azcurra, Argentina, 2012 | No. They merely write that participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 groups; intervention, active control and passive control. Participants were recruited from 2 privately funded long-term nursing homes sharing structural and functional characteristics. | Yes. To some extent. They state that the design is single-blinded and describe that the psychologists delivering the intervention were blinded to the outcome measures. The outcome measures were administered by independent raters (registered nurses). Further analysis of the data was done by statisticians who were blinded to the subject assignment (p. 426). | Yes. The percentage of missing data for the outcome variable at T0, T1, and T2 was 2.5% and the percentage of missing data for the independent variables was 1.9%. | Yes. Out of the 145 eligible cases, 5 dropped out during the study (death, moved to another facility, refused to participate). |

| Stinson et al, the United States, 2005 | No. They merely write that participants who met all eligibility requirements were randomly assigned with equal probability to either the experimental group or the control group. | No clear description. | No. | No. They state that complete data were obtained for 17 of the STS outcomes (29%) and 18 of the GDS outcomes (25%). Attrition occurred because of difficulty of completing all data across time. During the 6-week period, there were 2 hospitalizations, 1 relocation, and 1 decision from a participant to withdraw from the study. |

| Gudex et al, Denmark, 2010 | Yes. They write that the study was undertaken as a randomized, matched intervention study. Ten nursing homes were matched by the project team into 2 groups on the basis of location, type, and size. The 2 lists of 5 nursing homes were then placed in 2 blank sealed envelopes; a colleague external to the project group was asked to arbitrarily choose one envelope; the 5 nursing homes named in this envelope became the intervention group, who implemented reminiscence. The remaining 5 nursing homes became the control group who continued with usual nursing care. | Yes. Nursing homes were not told of their group until after the second baseline data collection was completed. Blinding of nursing staff with respect to intervention was not possible, although the project interviewers were not formally told which group the nursing homes were in. | No. | No. The dropout rate over the project period was 32% for residents. Of the 111 residents who failed to complete the study, 98 had died, 11 had moved out of the nursing home, 1 withdrew study participation, and 1 had become too ill. There were no significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the 348 who started the study and the 237 who completed the study. |

| Quantitative nonrandomized | 3.1 Are participants (organizations) recruited in a way that minimizes selection bias? | 3.2 Are measurements appropriate (clear origin, or validity known, or standard instrument; and absence of contamination between groups when appropriate) regarding the exposure/intervention and outcomes? | 3.3 In the groups being compared (exposed vs nonexposed; with intervention vs without; cases vs controls), are the participants comparable, or do researchers take into account (control for) the difference between these groups? | 3.4 Are there complete outcome data (80% or above), and, when applicable, an acceptable follow-up rate for cohort studies (depending on the duration of follow-up)? |

| Chao et al, Taiwan, 2006 | Yes. Purposive sampling was done to recruit participants; participants in experimental and control group were matched for demographic characteristics, depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. | Yes. Validated measures are applied. | Yes. Groups have been matched on relevant measures. | Yes. Attrition/exclusion were reported (2 in the experimental group and 4 in the control group) at follow-up (after the 9 weekly group sessions). There is a relatively short follow-up period. However, the follow-up time might be suitable for the specific outcome measures in the study (depression, self-esteem, life satisfaction). |

| Tsai et al, Taiwan, 2010 | Yes. Nursing homes were selected based on size and accessibility to the researcher. To compare participants in experimental and control groups, at least 30 participants in each group were needed. A list of 20 medium-large nursing homes were first obtained; these were all over Taiwan and were accessible to the researchers. Each of these nursing homes was assigned a number. Nursing homes for the control group were randomly selected by number and were approached to recruit participants until the goal of 30 participants was reached. The same procedure was followed for the experimental group. Six nursing homes rejected participation and few residents wanted to participate, so further nursing homes were approached to reach the 30 participants. | Yes. Validated measures are applied. | Yes. However, I am a bit uncertain here. They have a demographic table comparing the 2 groups on age, gender, marital status, education, residency, activities of daily living (ADL), and MMSE where for most of the variables the distribution is very similar (no tests). Furthermore they write that the same inclusion/exclusion criteria were used for both control and experimental group. They do not seem to control statistically for potential differences. | Yes. During the 3 months of this study, the control group lost 5 participants (28 remained, a 15% loss to follow-up), and the experimental group lost 3 participants (21 remained, 12.5% loss to follow-up). They state that participants who withdrew from the 2 groups did not differ significantly from those who remained in any demographic characteristic except age. |

| Winningham et al, the United States, 2008 | Yes. They write that all participants in a given facility were assigned to either the CEP or the control group. Participants within a given facility were all assigned to the same conditions, because they had previously observed that nonparticipating residents in the same facility might have been exposed to some aspects by hearing participants discuss parts of the intervention. Facilities were assigned to be part of the CEP or control simply based on location of the researchers and availability of a large room. | Yes. Validated measures are applied. | Yes. 73 participants began the study but 16 dropped out for various reasons. A series of analyses was carried out to assess whether participants who dropped out differed from those who completed the study. There were indications that those who completed the study were younger and had higher SS-A scores than those who dropped out, but there were no differences in SS-B scores and loneliness. | No. With 16 out of 73 dropping out, the dropout rate is 21.9%. |

Note. MMAT = McGill Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; STS = Self-Transcendence Scale; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; CEP = cognitive enhancement program; SS-A = Social Support Appraisal; SS-B = Social Support Behaviors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anne Sophie Bech Mikkelsen  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0333-3057

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0333-3057

References

- 1. World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. Vol. 2015 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:218-227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jessen MAB, Pallesen AVJ, Kriegbaum M, Kristiansen M. The association between loneliness and health—a survey-based study among middle-aged and older adults in Denmark [published online ahead of print July 7, 2017]. Aging Ment Health. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1348480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lund R, Nielsen LS, Henriksen PW, Schmidt L, Avlund K, Christensen U. Content validity and reliability of the Copenhagen social relations questionnaire. J Aging Health. 2014;26:128-150. doi: 10.1177/0898264313510033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lund R, Christensen U, Iversen L. Medicinsk Sociologi: Sociale Faktorers Betydning for Befolkningens Helbred. København: Munksgaard Danmark; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lasgaard M, Friis K. Loneliness in the Population—Prevalence and Methodological Considerations. Aarhus, Denmark: Center for Public Health and Quality Improvement; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Golden J, Conroy RM, Bruce I, et al. Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:694-700. doi: 10.1002/gps.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Due P, Holstein B, Lund R, Modvig J, Avlund K. Social relations: network, support and relational strain. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:661-673. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pitkala KH, Routasalo P, Kautiainen H, Tilvis RS. Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on health, use of health care services, and mortality of older persons suffering from loneliness: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A:792-800. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5797-5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Savikko N. Loneliness of older people and elements of an intervention for its alleviation. August 2008. 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. Accessed September 11, 2015. [DOI]

- 12. Drageset J, Kirkevold M, Espehaug B. Loneliness and social support among nursing home residents without cognitive impairment: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:611-619. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woods B, Spector AE, Jones CA, Orrell M, Davies SP. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao X, Zhang D, Wu M, et al. Loneliness and depression symptoms among the elderly in nursing homes: a moderated mediation model of resilience and social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:143-151. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moyle W, Kellett U, Ballantyne A, Gracia N. Dementia and loneliness: an Australian perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1445-1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pluye P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:529-546. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akhlaq A, McKinstry B, Muhammad KB, Sheikh A. Barriers and facilitators to health information exchange in low- and middle-income country settings: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:1310-1325. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Filan SL, Llewellyn-Jones RH. Animal-assisted therapy for dementia: a review of the literature. International psychogeriatrics. 2006. Dec;18(4):597-611. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Villanueva AL, García-Vivar C, Canga NA, Canga AA. Effectiveness of family interventions in nursing homes. A systematic review. InAnales del sistema sanitario de Navarra 2015. (Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 93-104). doi: 10.23938/ASSN.0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chao C, Chao J. The effects of group reminiscence therapy on depression, self esteem, and life satisfaction of elderly nursing home residents. J Nurs Res. 2006;14:36-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chiang K-J, Chu H, Chang H-J, et al. The effects of reminiscence therapy on psychological well-being, depression, and loneliness among the institutionalized aged. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;25:380-388. doi: 10.1002/gps.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karimi K, Karimi H. Effectiveness of integrative and instrumental reminiscence therapies on depression symptoms reduction in institutionalized older adults: an empirical study. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:881-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stinson CK, Kirk E. Structured reminiscence: an intervention to decrease depression and increase self-transcendence in older women. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:208-218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haslam H, Haslam C. The social treatment: the benefits of group interventions in residential care settings. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azcurra S, Luis DJ. A reminiscence program intervention to improve the quality of life of long-term care residents with Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34:422-433. doi: 10.1016/j.rbp.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gudex C, Horsted C, Jensen AM, Kjer M, Sørensen J. Consequences from use of reminiscence—a randomised intervention study in ten Danish nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsai T, Tsai H-H. Videoconference program enhances social support, loneliness, and depressive status of elderly nursing home residents. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:947-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winningham RG, Pike NL. A cognitive intervention to enhance institutionalized older adults’ social support networks and decrease loneliness. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:716-721. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Theurer K, Wister A, Sixsmith A, Chaudhury H, Lovegreen L. The development and evaluation of mutual support groups in long-term care homes. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33:387-415. doi: 10.1177/0733464812446866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ogilvie D, Egan M, Hamilton V, Petticrew M. Systematic reviews of health effects of social interventions: 2. Best available evidence: how low should you go? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:886-892. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.034199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Advancing Care—Research With Care Homes. NIHR Dissemination Centre; 2017. doi: 10.3310/themedreview-001931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elias S, Neville C, Scott T. The effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety and depression in older adults in long-term care: a systematic review. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36:372-380. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]