Abstract

Background:

Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) has several advantages over deceased donor kidney transplantation. Yet rates of living donation are declining in Canada and there exists significant interprovincial variability. Efforts to improve living donation tend to focus on the patient and barriers identified at their level, such as not knowing how to ask for a kidney or lack of education. These efforts favor those who have the means and the support to find living donors. Thus, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)-organized workshop recommended that education efforts to understand and remove barriers should focus on health professionals (HPs). Despite this, little attention has been paid to what they identify as barriers to discussing LDKT with their patients.

Objective:

Our aim was to explore HP-identified barriers to discuss living donation with patients in 3 provinces of Canada with low (Quebec), moderate (Ontario), and high (British Columbia) rates of LDKT.

Design:

This study consists of an interpretive descriptive approach as it enables to move beyond description and inform clinical practice.

Setting:

Purposive criterion and quota sampling were used to recruit HPs from Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia who are involved in the care of patients with kidney disease and/or with transplant coordination.

Patients:

Not applicable.

Measurements:

Semistructured interviews were conducted. The interview guide was developed based on a preliminary analytical framework and a review of the literature.

Methods:

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data stemming from the interviews. The coding process comprised of a deductive and inductive approach, and the use of a qualitative analysis software (NVivo 11). Following this, themes were identified and developed. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was obtained. In total, we conducted 16 telephone interviews as thematic saturation was attained.

Results:

Six predominant themes emerged: (1) lack of communication between transplant and dialysis teams, (2) absence of referral guidelines, (3) role perception and lack of multidisciplinary involvement, (4) HP’s lack of information and training, (5) negative attitudes of some HP toward LDKT, (6) patient-level barriers as defined by the HP. HPs did mention patients’ attitudes and some characteristics as the main barriers to discussions about living donation; this was noted in all provinces. HPs from Ontario and British Columbia indicated multiple strategies being implemented to address some of these barriers. Those from Ontario mentioned strategies that center on the core principles of provincial-level standardization, while those from British Columbia center on engaging the entire multidisciplinary team and improved role perception. We noted a dearth of such efforts in Quebec; however, efforts around education and promotion, while tentative, have emerged.

Limitations:

Social desirability and selection bias. Our analysis might not be applicable to other provinces.

Conclusions:

HPs involved with the referral and coordination of transplantation play a major role in access to LDKT. We have identified challenges they face when discussing living donation with their patients that warrant further assessment and research to inform policy change.

Keywords: health professionals, living donor kidney transplantation, barriers, Quebec, Ontario, British Columbia

Abrégé

Contexte :

La transplantation de reins provenant de donneurs vivants présente de nombreux avantages comparativement aux greffes d’organes provenant de donneurs décédés. Pourtant, les taux de greffes de reins provenant de donneurs vivants (GRDV) sont en baisse au Canada et varient beaucoup d’une province à l’autre. Actuellement, les efforts déployés se concentrent principalement sur les patients et des obstacles les touchant; le manque d’information ou le fait qu’ils ignorent comment demander un rein, notamment. Les patients ayant les moyens et le soutien pour trouver un donneur vivant sont ainsi favorisés. Un atelier organisé par l’IRSC a recommandé que les efforts visant la compréhension et l’élimination des obstacles à la GRDV se concentrent davantage sur les professionnels de la santé (PS). Néanmoins, peu d’attention a été accordée à ce que ceux-ci perçoivent comme des entraves à discuter d’une GRDV avec leurs patients.

Objectif :

Nous voulions savoir ce que les PS de provinces canadiennes avec un taux de GRDV faible (Québec), moyen (Ontario) et élevé (Colombie-Britannique) considéraient comme des entraves à discuter de la procédure avec leurs patients.

Type d’étude :

L’étude est une approche interprétative descriptive puisqu’elle dépasse la description et qu’elle est susceptible d’orienter la pratique clinique.

Cadre :

Des critères choisis à dessein et un échantillonnage par quotas ont été employés pour recruter des PS québécois, ontariens et britanno-colombiens impliqués dans les soins aux patients atteints de néphropathie et/ou dans la coordination des greffes.

Sujets :

ne s’applique pas.

Mesures :

Des interviews semi-structurées ont été menées. Le guide de l’interview a été élaboré à partir d’une grille d’analyse préliminaire et d’une revue de la littérature.

Méthodologie :

Les données tirées des interviews ont été examinées par analyse thématique et le procédé de codage comportait une approche déductive et inductive, de même que l’utilisation d’un logiciel d’analyse qualitative (NVivo 11). Les principaux thèmes ont été dégagés puis développés, et les interviews ont été menées jusqu’à l’obtention d’une saturation thématique. Un total de 16 interviews téléphoniques a ainsi été mené.

Résultats :

Six principaux thèmes ont été dégagés : (1) le manque de communication entre les équipes de dialyse et de transplantation; (2) l’absence de lignes directrices pour l’aiguillage; (3) la perception des rôles et le manque d’implication de l’équipe multidisciplinaire; (4) le manque d’information et de formation de certains PS; (5) les perceptions négatives de certains PS à l’égard d’une GRDV et; (6) les difficultés liées directement aux patients. Dans chaque province sondée, les PS ont mentionné que l’attitude des patients et certaines caractéristiques consistaient les principales entraves à discuter d’une GRDV. Selon les répondants ontariens et britanno-colombiens, plusieurs stratégies sont actuellement mises en œuvre pour pallier ces difficultés. En Ontario, on mise sur l’application provinciale des principes fondamentaux de normalisation, alors qu’on se concentre plutôt sur l’implication de l’équipe multidisciplinaire et l’amélioration de la perception des rôles de chacun en Colombie-Britannique. Un manque d’efforts en ce sens a été observé au Québec, bien que de timides mesures de sensibilisation et de promotion aient émergé.

Limites :

En plus de biais de sélection et liés à l’acceptabilité sociale, notre analyse pourrait ne pas s’appliquer aux autres provinces.

Conclusion :

Les professionnels de la santé impliqués dans l’aiguillage et la coordination des greffes jouent un rôle essentiel dans l’accès à une transplantation de rein provenant d’un donneur vivant. Nous avons identifié les difficultés qu’ils perçoivent à discuter d’une GRDV avec leurs patients; des défis qui justifient une évaluation et des recherches plus poussées en vue d’éclairer les changements d’orientation.

What was known before

Rates of living donor kidney transplantation are declining. Current efforts focus on implementing educational interventions to address patient-identified barriers to living donation. A CIHR-organized workshop recommended that education efforts to understand and remove barriers should focus on health professionals instead as they play a crucial role in a patient’s decision to pursue living donation.

What this adds

We interviewed health professionals across 3 provinces of Canada with variable rates of living donor kidney transplantation. We report 6 themes that they perceive as barriers, most of which are easily modifiable. Our findings can help inform health delivery systems of targeted and effective interventions.

Introduction

Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is associated with superior patient and graft survival when compared with deceased donor kidney transplantation.1-4 Those with LDKT experience lower rates of acute rejection, have earlier access to a transplant, and have an improved quality of life.2,5-12 Thus, there is considerable interest in increasing LDKT.4,11,13-18 Yet the overall rate of living donation in Canada is declining (16.8 per million population in 2007 to 15.2 per million population in 2016) and is 35% lower than several other Western nations.3,4,8,11,12 Furthermore, there exists significant interprovincial variability in LDKT rates. For example, in the provinces of Quebec (QC), Ontario (ON), and British Columbia (BC), <15%, 30%-40%, and 50-60% of the transplants done annually are from living donors, respectively.3

Patient-identified barriers to LDKT, such as patients’ discomfort to approach potential donors and lack of knowledge, are well recognized.11,19-27 We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of educational interventions to address these barriers and noted that they were associated with a 2.5 higher odds of LDKT when compared with nonspecific education.28 However, the quality across studies was mixed and we noted high risk of selection bias. Also, some of the more effective interventions are resource intensive and might not be sustainable at most centers.28,29 More importantly, it has been argued that shifting the burden of finding a donor to the patient has created an inequitable 2-tier system favoring those who have the social and financial means to learn this process and pursue LDKT.10,30 This has been systematically shown; a socioeconomic advantaged quartile of patients was 34% more likely to receive LDKT when compared with the most disadvantaged quartile.31

Overall, less attention has been given to barriers stemming from the health professional (HP). These HPs include physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, and other staff at dialysis and transplant centers who are involved in the care of patients with kidney disease and/or with transplant coordination. A Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)-organized workshop recommended that education efforts to understand and remove barriers should focus on HPs.32 This is because the crucial role of HPs, especially nurses, in a patient’s decision to pursue LDKT is well recognized.13,33-41 It is also known that personal biases, lack of knowledge, and discomfort can lead to inconsistent and inexplicit recommendations, and that this may intensify inequity to LDKT especially in the disadvantaged populations.21,22,42-45 Previous studies have only focused on issues surrounding wait-listing and transplantation at the center- and system-level.43,46-54 When HP-level barriers to LDKT were examined, studies focused on nephrologists only42,55-57 and the input of frontline staff, such as dialysis nurses, was not captured. This is problematic due to a variety of reasons. First, decision-making on LDKT eligibility entails unique ethical, cultural, psychosocial, and medical uncertainties. Making this decision unilaterally may be reflective of an individual’s own perceptions and biases. Second, for nephrologists LDKT education may not be a priority given competing needs to educate on a myriad of other issues related to dialysis.53 Physicians might think they are not accountable for transplant education.54,55 Last, education delivered by the physician might be ineffective.43,58

Given this, the aim of our study was to systematically explore HP-identified barriers to discussions of LDKT with patients in 3 provinces of Canada. We wanted to capture the input of those who are involved in the care of patients with kidney disease and/or with transplant coordination. We also aimed to explore if there are differences among HPs when informing their patients about living donation in 3 provinces of Canada with low, moderate, and high rates of LDKT.

Methods

Study Design

This is an interpretive descriptive study with the aim of developing a conceptual understanding of a phenomenon to inform clinical practice.59 Interpretive description draws from various methodological approaches (grounded theory, ethnography, and phenomenology) to provide a basis upon which to analyze data that goes beyond description and is oriented toward theory development. Interpretive description rests on both naturalistic and constructivist epistemologies in emphasizing the central role of researchers in the interpretation of data; the latter not so much emerging by itself but rather stemming from decisions the researcher makes in generating findings.59,60 Thus, while interpretive description involves some form of theory development, it is in line with practical orientation.

Preliminary Analytic Framework: O’Neill et al’s Clinical Decision-Making Model

Interpretive description calls for the development of a preliminary analytic framework that will serve as theoretical scaffolding by guiding aspects of the study design, such as the elaboration of data collection instruments, while data analysis will take shape through the interplay between the empirical data and this preliminary framework.59,61 To understand what impedes HPs willingness or ability to engage in a discussion about LDKT with patients, a perspective around what shapes the decision-making process around assessing patients for referral and eligibility for LDKT, and the place discussions with patients occupy in that sense becomes useful. Thus, HP barriers to discussion need to be situated as part of the selection and evaluation of patients for LDKT, as well as how HPs perceive and define the barriers in that regard, particularly as they relate to discussing LDKT with patients. To that end, our preliminary analytical framework draws on aspects of O’Neill’s clinical decision-making model as found in Banning62 and O’Neill et al63,64 and was adapted to issues pertaining to LDKT and HP-level barriers (Table 1). The main components related to clinical decision-making, according to this model, are as follows: (1) pre-encounter data which may include the role of guidelines, policies, procedures, prior knowledge, beliefs, assumptions about patients, and how risk is anticipated and controlled by HPs regarding LDKT; (2) situational and client modifications, that is interactions between HPs and patients, and the management of the patient’s care in particular environments (which may involve interactions and discussions related to LDKT) as well as organizational and resource issues; and (3) hypothesis generation, or the extent to which decisions are made on the basis of the patient’s condition or pattern recognition. With regard to LDKT, this pertains to what enters into the assessment and evaluation of patients and, in particular, how discussions with patients come into play. The aim thus becomes that of understanding how these 3 components interrelate with regard to HPs’ decisions in relation to LDKT and the manner in which discussions about LDKT with patients is enabled or inhibited as a result, and the place such discussions hold in assessing and referring patients for LDKT. Thus, our preliminary analytical framework drew on aspects of O’Neill’s clinical decision-making model and was adapted to issues pertaining to LDKT and HP perceived barriers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

O’Neill’s Clinical Decision-Making Model Adapted to LDKT and Health Professional–Identified Barriers.

| Component of the model | Aspects related to current study |

|---|---|

| Pre-encounter data | - Prior knowledge/familiarity of LDKT - Prior experiences with LDKT (or kidney transplantation) - Biases (LDKT and/or patients) - Assumptions regarding LDKT and patients Anticipating and controlling risk - Guidelines, protocols, procedures |

| Situational and client modifications (environment) | Client - Discussions between patients, potential donors, and HP (with whom, under what circumstances) - Patient characteristics; condition Situational - Procedural barriers or challenges encountered in relation to LDKT - Organization of renal services; referral process - Resources - Sources of support |

| Hypothesis generation (patient-specific information vs pattern recognition or evidence about LDKT) | - Assessment for eligibility of the patient - How evidence is evaluated and weight given to various types of evidence - Decisions made regarding eligibility on the basis of the patient’s condition or other patient characteristics |

Note. LDKT = living donor kidney transplantation; HP = health professionals.

Sampling and Recruitment

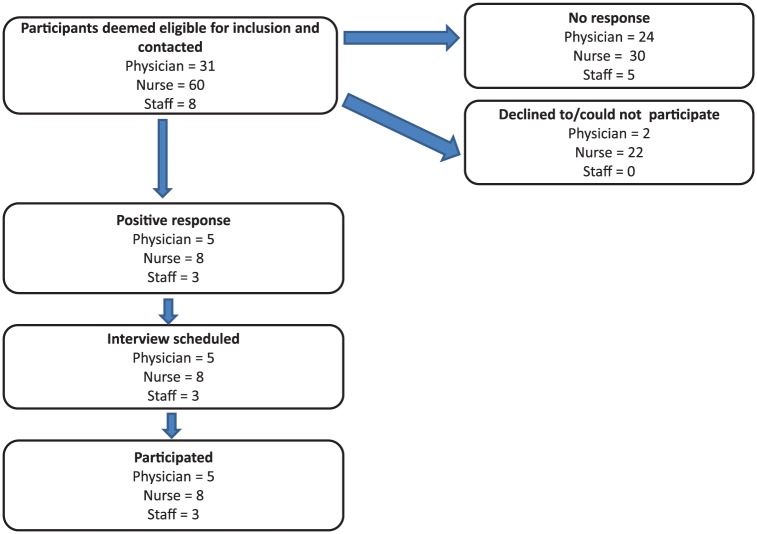

A directory of dialysis centers, and transplant and nephrology clinics across Canada was used to create a recruitment list. Participants were selected by contacting the centers directly and based on referrals and were contacted via a letter of invitation (email or mail) or by telephone. Two sampling strategies were used to recruit potential participants.65 The first step involved purposive criterion sampling to ensure the input of key stakeholders, such as transplant coordinators, dialysis nurses, and general nephrologists, was captured. Exclusion and inclusion criteria, as put forth in Table 2, were developed and used to select potential participants. We wanted to include the opinions of those who are involved in transplant coordination. Our focus in recruiting participants was HPs working either in chronic kidney disease clinics, dialysis centers, or within programs that combined these two with transplantation. Also, to ensure that key demographics were represented, this study resorted to a quota sampling method. We wanted to ensure that a minimum percentage of participants with certain characteristics, summarized in Table 3, were represented in the sample.65 The recruitment process is outlined in a consort diagram (Figure 1). Participants who did not respond were contacted up to 3 times. Interviews were conducted over the telephone usually in the office setting by a senior qualitative researcher (K.C.).

Table 2.

Selection Criteria for Recruitment of Participants.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| - Involved in the care of patients who have kidney disease, are on dialysis, whether hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or home dialysis - Nephrologists, unit directors, head nurses/nurse managers as well as nurses, but may also include other staff members working in dialysis, in particular home dialysis - Healthcare professionals involved in transplant coordination to the extent that they interact with patients seeking a kidney transplant, or experience working with patient donors and/or recipients, or have been suggested by other participants as important to talk to - Particular attention was given to those working in dialysis, in particular in home dialysis |

- Healthcare professionals defined as working specifically in the area of kidney transplantation - Those defined as working in renal services, as it remained unclear as to whether this may include kidney transplantation |

Table 3.

Targeted Sampling Quotas and Percentage of Participants Who Were Recruited.

| Characteristic | Targeted quota (%) | Recruited % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Role | ||

| Physician (nephrologist) | 20 | 31 (5) |

| Nurse | 20 | 50 (8) |

| Other | 19 (3) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 20 | 19 (13) |

| Female | 20 | 81 (3) |

| Experience in the field of nephrology | ||

| 10 years and less | 20 | 62 (10) |

| More than 10 years | 20 | 38 (6) |

| Transplant centers per province | ||

| Québec | 20 | 50 (8) |

| BC | 20 | 25 (4) |

| Ontario | 20 | 25 (4) |

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of recruitment process of participants per province.

This study was approved by the local institutional review board and written consent was obtained from all participants; participation was voluntary. Participant information procured was coded and de-identified by order of interview and province of work. The qualitative researcher (K.C.) who conducted the interviews labeled the interview tape with a code number and transcribed it. Any information in the transcript that identified the participant was removed. Upon receiving the transcript, the audio recording was destroyed. The study files were kept in paper or electronic format in secure and locked filing cabinets.

Data Collection

We conducted 16 semistructured telephone interviews with participants working in three Canadian provinces: 8 in QC, 4 in ON, and 4 in BC. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and conducted between October 2017 and March 2018. Recordings lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. All transcriptions were verified for accuracy by directly comparing voice and transcription files. Only 1 interview was repeated, as per the participant’s request. Interviews were conducted over the telephone usually in the office setting by a senior qualitative researcher (K.C.). On the basis of aspects of the initial analytical framework as well as a review of the literature, an interview guide was developed and covered the following topics: (1) familiarity, knowledge, and interest with LDKT; (2) potential biases surrounding patients and LDKT; (3) participants’ involvement and comfort level with LDKT; and (4) final thoughts regarding LDKT.

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis66,67 was used to analyze the data stemming from interviews using an inductive approach.68 To do this, potential and emerging themes were contrasted with the preliminary framework to develop an explanatory framework around the barriers to discussion about LDKT in the following manner: the coding process comprised a deductive and inductive approach and was accompanied by the development of a preliminary codebook informed by elements of the interview data, the preliminary framework, and a review of the literature. Codes that emerged from the data were then added to the codebook.

The coding process involved the use of a qualitative analysis software (NVivo 11). Following the coding process, codes were clustered to develop initial themes, which were then refined so as to ensure their internal and external heterogeneity.69 Memoing throughout the coding process served to facilitate the clustering of codes and guide theme development.70 More specifically, memoing served to establish relationships between initial ideas stemming from the coding process as to how various barriers impede discussions to occur between patients and HPs. Narrative summaries for each interview were also developed and accompanied the coding process as well as guided theme development.

Once coding was completed, codes were then grouped into categories. This took shape as codes were clustered such that they shared common ground in relation to the research question, the phenomenon under study, and aspects of the preliminary framework that is perceived facilitators and impediments to discussing LDKT with patients. This enabled theme development. Thus, theme identification and development followed the stages as laid out by Vaismoradi and colleagues.67 These stages included (1) classification or typification (the classifying of codes that share typical similarities); (2) comparison and revision of codes; and (3) the sorting of codes under labels (taken from the content of the transcript but which entailed more abstraction than the classification phase). Data were coded by a qualitative researcher (K.C.) and subsequently verified by a second senior researcher (J.F.F.).

Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was obtained. Francis et al’s71 approach was drawn upon to assess thematic saturation. An initial sample of 10 interviews was established. Additional interviews were conducted until saturation was achieved, that is until no new significant changes were made to the codebook (Supplementary Table 1).72 A saturation table or grid was designed around the codebook as a way of keeping track of changes to the codebook.73 This procedure was followed in accordance with the quota sampling strategy to ensure the representativeness of certain characteristics. Tong et al’s74 consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research were drawn upon to ensure the quality of the methods used for this study were robust.

Results

Overall, 81% of the participants were female, 31% were physicians, 50% were nurses, and 19% described themselves as other staff (Table 3).

Themes

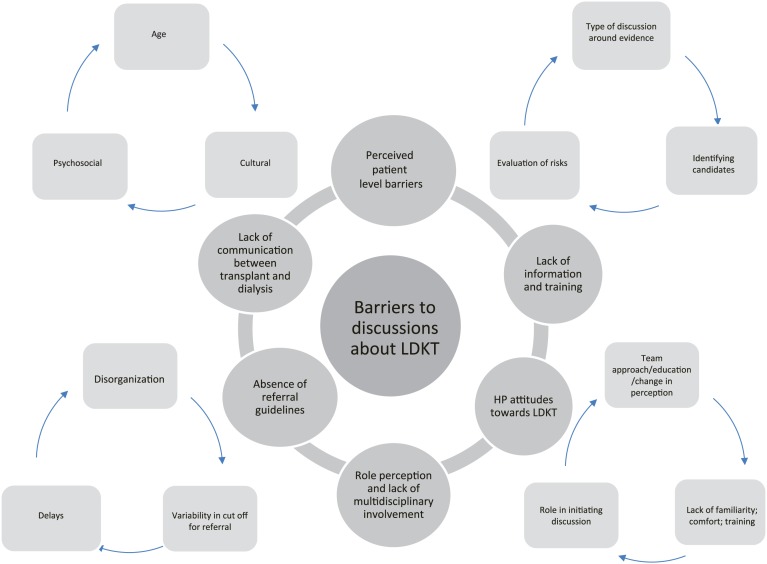

Six predominant themes emerged from what HP identified as barriers to discussing LDKT with their patients (Figure 2). Table 4 describes specific quotes supporting each theme.

Figure 2.

Themes and subthemes around health professional (HP)-level barriers to discussions about living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) with patients.

Table 4.

Illustrative Quotes for the Themes Identified in This Study of Health Professional–Identified Barriers to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation by Province (Efforts Implemented to Alleviate Some Recognized Barriers Are Highlighted).

| Theme | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Lack of communication between transplant and dialysis teams | Québec: • There’s a lot of problems with communication there. You know, the pre-dialysis clinic will send a patient for referral and kind of not hear back. (11-QC) • So we’re never sitting at a table together unless it’s about something really problematic. . . . It’s like this black box. Patient goes for transplant and there’s this whole work-up and then they get the call and we do the dialysis pre and we hope everything goes well for them but . . . we’re not really part of the process. (14-QC) Ontario: • Right now what just happens is, you know, the process goes on for six months, nine months, whatever and a letter, at the end, is issued to the potential donor and the referring nephrologist is saying they’re not eligible, you know, and the recipient never heard anything about it. (08-ON) • And we sort of know by the bye what’s going on, and we’ll see notes here and there, and investigations. And our coordinator is wonderful at keeping us up to date. . . . It’s a very cooperative process in Ontario. We have an annual transplant forum where all the transplant centres get together, then invite the community units like myself to attend. And it’s a very good process, you know. So we all know each other well and communicate with each other well. (15-ON) • Yeah, so previously I think communication was not perfect but we have been trying to inform the programs. But over the last year or so at our center there are fairly kind of specific protocols about communications, and then we are sending letters both to the patient and the transplant nephrologist and the dialysis units about wait-listing, start to send if the patient received a transplant as well. (16-ON) British Columbia: • You know, you don’t—and you’re not part of the process at all of a living donor kind of coming through and how they came through their stages. . . . We always feel like transplant is another subspecialty. (05-BC) • And so, it’s one of the things that we’ve actually identified to the coordinator in this new position is that, there has always been a disconnect communication wise and training wise between the transplant teams and the frontline home teams. (06-BC) |

| 2. Absence of referral guidelines | Québec: • Yeah. So I find the referral process a little bit disorganized . . . There isn’t no clear cut off and no clear guideline as to what needs to be done before the patient is referred. So that process right now is a little bit confusing. (11-QC) Ontario: • I think that the referring centers are getting better at identifying their patients who are heading towards end-stage kidney disease and that there’s been a real drive in the province with the Ontario Renal Network and with Trillium Gift of Life Network on improving those referral rate. (04-ON) • Yeah, so there’s a standard battery attached that has to be done on the recipient, prior to the recipient actually seeing the transplant nephrologist. I think that’s pretty standardized across the province now. This is still a work-in progress. . . . Where the lack of standardization comes in, generally, is after the recipient has seen the transplant nephrologist there’s still a fair bit of variation from transplant center to transplant center. (08-ON) British Columbia: • The work-up itself is quite daunting. (05-BC) • Admittedly it’s not a structured process. . . . So, the province here has actually, from a renal perspective, the province has actually just delegated a one year trial position for a pre-transplant coordinator. (06-BC) |

| 3. Role perception and lack of multidisciplinary involvement | Québec: • Yeah, that’s it. We, if we find that there are questions, I, among others, I communicate with the nurse of the transplant. . . . they will schedule an appointment with the nephrologist of the patient, so he meets the person, then he answers their questions. (10-QC) • You don’t discuss transplant to the same extent that like, you know, the surgeon will. . . . not to the same extent as when they go there and they meet the coordinators and they have like basically an hour talk where they describe how the whole transplant process works. (11-QC) • . . . when they see the nephrologist we encourage them to ask questions and to discuss it with them. (12-QC) • I, my role, doesn’t really involve the referral of patients for organ and tissue donation unless the patient actually happens to come to me in particular. (14-QC) Ontario: • But certainly I think academic centers are better equipped, in many cases, to have multiple levels of people who will raise this issue, so you’re not so heavily dependent on just a nephrologist saying this, you know, this patient is appropriate. (08-ON) • So multiple people. We have multidisciplinary staff in our clinic, and I think multiple disciplines will initiate the discussion. But mostly it’s the doctor, the nephrologist and then secondly the nurse. (15-ON) British Columbia: • So I certainly—it’s not my primary role to discuss transplant but it certainly comes up in conversation and I try to direct people to resources and encourage them to look for living donors. (01-BC) • I think the team approach to all of this has worked better for us and involvement of social workers has done great things for our program, and I think they’re under-recognized in their role in this and our social worker has been totally—her work has been fantastic in trying to move us forward in this way. (05-BC) • We did a two hour session yesterday and what we strategically did is we actually brought our entire team in. So, we actually had our clerk involved in the session, we had our dieticians involved in the sessions. (06-BC) • So sometimes there are differences in understanding, but the nephrologist thought they explained well enough, but patients didn’t really understand that that meant that they would be working on the transplant and in the workup and all that stuff. (13-BC) |

| 4. HP’s lack of information and training | Québec: • I think there’s just a general overall misunderstanding or lack of information on the impact of being a donor and what’s involved. (02-QC) • Well transplant was a large part of my training, but exposure to live kidney donation was minimal . . . But I think in terms of explaining the risks that’s something that the general nephrologist can do and in my experience it’s not necessarily that the risks are overestimated. It’s just that they have to be explained very carefully because there’s some nuance, you know. (11-QC) • I can’t really say that I’m 100% comfortable . . . But I can’t say I’m really equipped with different approaches or ways to bring it up to a family member or friend if you have a patient that’s looking to find a donor. (12-QC) Ontario: • Frequent discussions about the data helps we find, that if we’re continuing to see the data that people with—who’ve donated a kidney do well, you know reminders about how well they do seem to help us here in getting kind of surges of more positive discussions with patients. (05-ON) • Oh I feel very comfortable. I’ve been doing it for 30 years. I feel very comfortable. (15-ON) • Yeah, so clearly that is an issue, both living donor but transplant in general—and the Ontario Renal Network that is the government agency in Ontario who manages dialysis—did an environmental scan and needs assessment prior to 2017—it was I think between 2014 and 2016—and they identified that about two-thirds of the dialysis nurses do not feel comfortable discussing transplant-related issues, but specifically living donor-related issues with the patients. So clearly there is huge need for more discussion, more awareness, more knowledge and more comfort in terms of the frontline workers. (16-ON) British Columbia: • So it’s just re—just we can’t let it laps in-between, we have to do regular reinforcement of the data showing how much better people do with a living donor and how well donors do. (05-BC) • So, I would say that very succinctly that those have been moments where then staff struggle with; are we doing the right thing by promoting this. But those are rare situations that then you know, we have honest conversations with the nephrologist and, you know, and we have our fears, you know, explained and so we are able to move past those. We have two new staff, two new nursing staff, one with no renal background, she comes from diabetes and another who is new to renal and then new to my team. And so, of course, there is fears and anxiety for them, but simply just because they haven’t reached that point of feeling that they’ve got all the education. (06-BC). |

| 5. Negative attitudes of some health professionals toward living donor kidney transplantation | Québec: • I think that some people may think that the risks of being a donor are higher than they really are. . . . Some people I think still think that people have to be identical matches and they don’t . . . Transplantation is like another world ! . . . When we don’t know about something, it scare us. (02-QC) • And we have doctors who do not believe in transplantation, in general. Then we’re going to have a lot more trouble getting live donors to patients in those centers. . . . I think it has a lot to do with the mentality among some doctors, whether they are old school or of the new school. The new school is more . . . younger doctors are more proactive in terms of encouraging living donation. The old guard, maybe a little less. Probably due to bad knowledge about transplantation in general, whether deceased or living. (03-QC) • In general rule, I don’t really feel like there’s that much bias. I feel like usually people are quite in favour of referring patients. (11-QC) Ontario: • So, you know, there’s nobody in our group here, either physician or amongst the transplant coordinators and the nursing staff, who have any really differing opinions on the appropriateness of, you know, trying to expand the donor and recipient pool as much as possible, to really anybody who is likely to benefit from a transplant. (08-ON) • I’m a strong proponent of transplant . . . If I have the slightest thought that a patient might be a candidate in my own mind, I make the referral. (15-ON) British Columbia: • So I sometimes wonder if people are like oh, well lots of people are getting transplants now, I don’t have to worry about finding a living donor, but I know that no matter what a living donor is going to promote or provide them with the best health outcomes. So it’s still the best option for the patient. (01-BC) • I think there’s just a little bit of a shift from each of the specialties about how they perceive it, and what has been interesting for us is to make sure everybody’s getting on the same page. (05-BC) • Everybody’s really very involved and we all believe in the process so, it’s not a hard sell for us . . . Yeah. So, our nursing team 100% is fully engaged, our social worker team is 100% fully engaged and very enmeshed in it. (06-BC) |

| 6. Patient-level barriers as defined by the health professional | Québec: • Because the wait list isn’t as long on the deceased donor list maybe people aren’t feeling the pressure to look for a donor. (02-QC) • They are clumsy, they are afraid to ask their family, they are afraid, I think they are a little embarrassed. Because sometimes, we have the language barrier too . . . So, if it’s someone who just speaks Tamil, or you know a lot of others . . . There are so many communities represented here (07-QC) • There is a fantasy side of the transplant, which is the miracle cure. (10-QC) • So in my experience the risks are not overestimated when discussing it with patients . . . Yeah. Especially like when you have a young patient so maybe like less than, you know, like 50 who’s working and who had a family and who has a partner then, you know, a lot of effort is made into convincing them that live donation is better and really making an effort about talking about it around them. (11-QC) • So I think mostly it’s age and their general health are main issues. (12-QC) • So a lot of my patients think transplant equals cure. (14-QC) Ontario: • We have a very diverse patient population who are referred to us where English is not necessarily their first language, that they’re recent immigrants, there are socioeconomic factors that are playing into it, cultural beliefs, unwillingness to consider a living donor in particular some cultural groups. (04-ON) • But our patient population is increasingly heterogeneous, and it’s harder and harder to have specific, very, very specific guidelines that apply in all cases. (15-ON) • But unfortunately the resources are very scarce so it’s very difficult to provide additional support for patients who have issues with substance use, for example, or non-adherence. And so some of these patients probably will not be referred for transplant. (16-ON) British Columbia: • There seems there has been a reduction in living donors in BC that corresponds with the increase in deceased donors. (01-BC) • I think those would be the biggest ones is cost and travel and being separated from family. (05 BC) • From the patient perspective, the barrier I would say that you know, sadly the typical thing is the patient themselves is a barrier. (06-BC) • Well, there’s always some patients who don’t have any absolute contraindications, but some patients may have, what’s the word, like more psychosocial issues or compliancy issues or something like that. (13-BC) |

Lack of communication between transplant and dialysis teams

Certain organizational characteristics were thought to impede early discussions with patients about LDKT. Dialysis and transplant teams were viewed as separate entities. Communication between them was deemed as sporadic and insufficient, and to only occur during a crisis situation. HPs working in dialysis felt not being sufficiently updated on the progression of recipient’s and donor’s evaluation. The transplant team was likened by 1 participant to a “black box” of which the dialysis team was excluded (14-QC). This hindered the possibility for HPs in the referral center to engage in discussions about LDKT. In addition, establishing the donor evaluating team as a separate entity was viewed as problematic, especially when a majority of donors that initiate the process have an excellent relationship with the recipient (08-ON).

Participants from ON and BC mentioned efforts being made to alleviate this separation via coordinators and protocols, and that this translated into improved communication. Yet even in the midst of such efforts, the transplant team and the transplant coordinator remained perceived as being best suited to engage in detailed conversations about LDKT, while more general conversation are left to the referral team. Thus, the difficulty in attenuating dialysis and transplant teams/centers as separate entities hinders the possibility for HPs in the dialysis centers to become part of the process of pursuing a LDKT.

Absence of referral guidelines

The current referral process surrounding LDKT was deemed as encumbered by numerous tests and delays. Some felt that if these tests are done ahead of time it delays the referral. Disorganization was another characteristic used to describe the referral process, as many pointed to variability in the cutoff and tests required prior to referral for transplantation. Part of this is deemed attributive to dialysis and transplant teams remaining separate entities. All this contributes to confusion and decreased early discussion with patients about LDKT.

As efforts to alleviate this, many mentioned that the focus should be on establishment of referral guidelines at the provincial level to streamline the referral process. In the absence of such guidelines, the potential for early discussions about LDKT is curtailed on account of the confusion that characterizes the referral for transplantation; a confusion stemming from persistent variations among centers. In ON this constitutes a core effort to facilitate LDKT. Some said that variations will remain in the application of these guidelines, but as one participant said, “You can never . . . I don’t think you can ever fully standardize something where human beings are involved in making decisions but you can still . . . there’s definitely room there” (08-ON). Another option put forth was early referral of the patient to the transplant center, thus situating the role of early discussions with patients about LDKT to the transplant team.

Role perception and lack of multidisciplinary involvement

The manner in which some participants perceived their role and that of others represented another barrier. Many HPs did not consider it to be their role to discuss LDKT with patients, but rather that of the transplant team or the nephrologist. Thus, they forego this discussion as they perceived limits to the appropriateness of initiating a LDKT discussion, given their expertise, ability, and role expectations. Some participants nonetheless considered it necessary to raise the issue of LDKT with patients whenever possible.

The extent to which multidisciplinary teamwork invites frontline workers to alter their role perception was deemed crucial to engage in discussions about LDKT with patients. This is to say whether HPs viewed discussions with patients about LDKT as outside their role to one in which such discussions were thought of as key to their role. Participants from BC alluded to teamwork and opportunities for informal discussions by frontline staff as central to facilitating LDKT. This was accompanied by a change in role perception and increased familiarity and comfort in raising this topic with patients by every member of the team. The notion of a nephrologist working alongside other HPs, while retaining a central role, was viewed as conducive to facilitating discussions about LDKT.

HP’s lack of information and training

HP lack of comfort in communicating the risks and benefits of LDKT to patients emerged as a barrier, particularly in QC. This was attributed to lack of training and knowledge regarding LDKT, and lack of resources and up to date information. A living donor coordinator working in QC pointed out that the existence of strict criteria for donor assessment tends to be inflated among HP in dialysis centers due to the lack of knowledge and comfort (02-QC). HPs at the predialysis phase lack the necessary information and knowledge to address patients’ concerns, which were said to revolve around the risks for the donors. Some participants indeed admitted to feeling discomfort discussing LDKT with patients, in particular issues surrounding finding a donor. Also, the existence of strict criteria for donor assessment tends to be inflated among HPs at dialysis centers. Thus, in overestimating the risks of LDKT and compounded by their own sense of lacking the information necessary to address patients’ concerns, HPs refrain from engaging in this conversation.

On the contrary, in ON and BC participants reported that discussions with patients not only occur earlier but are characterized by presenting patients with the evidence surrounding LDKT, dispelling any myths they may have had and offering support. Such discussions become integral to the referral process as the patient’s willingness to get a transplant becomes thought of as paramount to that process. At the same time, it is important to note that this lack of comfort and knowledge discussing LDKT with patients was mentioned by one participant in ON (16-ON). Also, the need for continued education, frequent discussions, and review of data was mentioned to continue to reinforce the benefits of LDKT, especially when there is a rare occurrence of a bad donor outcome (06-BC). A participant from QC reiterated this interest in increasing training in how to discuss LDKT with patients; even expressing willingness on their part to organize such a session themselves (07-QC).

Negative attitudes of some HPs toward LDKT

Participants interviewed in this study expressed enthusiasm for LDKT, although a few participants, most notably in QC, mentioned some HPs’, in particular nephrologists’, attitude against LDKT as an impediment. One participant said,

And we have doctors who do not believe in transplantation, in general. Then we’re going to have a lot more trouble getting live donors to patients in those centers. . . . I think it has a lot to do with the mentality among some doctors, whether they are old school or of the new school. The new school is more . . . younger doctors are more proactive in terms of encouraging living donation. The old guard, maybe a little less. (03-QC)

The positive attitude toward LDKT in ON and BC, both among nephrologists as well as other HPs, was propelled by efforts to widen the eligibility of patients, which has led to increased emphasis on early discussion and referral. Participants attributed this to an aggressive “culture change” with the aim of rendering transplant, in particular LDKT, as the gold standard in treatment of patients with renal disease. In ON, potential recipients were described as being identified upon the slightest possibility as to their eligibility for LDKT. In BC, discussions with patients’ occurred earlier and centered on presenting evidence and offering support.

Patient-level barriers as defined by HPs

HPs’ own accounts of encounters with patients reflected a propensity to pinpoint patients’ attitudes and characteristics as the main barrier to discussions about LDKT. This was noted in all provinces. HPs mentioned barriers with respect to cultural background, psychosocial issues, language barriers, belief systems, and age. These rendered discussions with patients difficult. Many described that there is more willingness to convince younger patients to resort to living donation. Education sessions tailored to specific cultural groups were said to have been developed. Also an increasingly heterogeneous patient population was viewed as adding difficulty to efforts aimed at standardizing discussions with patients. Some mentioned that patients who are overenthusiastic as a problem due to engendering unrealistic expectations, and sometimes leading to a potential loss of motivation in pursuing LDKT. In another instance, some participants went so far as to wonder if an increase in deceased donors served as a disincentive for patients to find a living donor (01-BC; 02-QC).

Most mentioned placing the bulk of the responsibility on patients. Patients were portrayed as fearing to approach potential donors and not knowing how to formulate their request. Some described instances where patients did not inform family and friends of their renal disease, even though they are being called upon to act as spokespersons or advocates on behalf of the patient. Participants mentioned that patients are oriented toward tools aimed at helping them find a donor and provided support, but they do not play a direct role in the process of finding a donor.

Potential Causes of Disparity in LDKT Rates

Although not recognized by HPs, we noted significant interprovincial variations in efforts to increase LDKT (Table 5). Participants from regions with moderate and high rates of LDKT repeatedly mentioned multiple initiatives in their regions (comments in bold in Table 4). HPs from ON mentioned strategies that center on the core principles of provincial-level standardization, while those from BC center on engaging the entire multidisciplinary team and improved role perception. In addition, HPs mentioned several efforts to improve communication between treating teams and continued education of frontline staff. The efforts in BC are so immense that one participant said, “I’m not really sure how much more we need because over all at this program, everybody’s really very involved and we all believe in the process so, it’s not a hard sell for us” (06-BC). We noted a dearth of such efforts in QC. One participant mentioned the ongoing nursing crisis,75 “The transplant nurses feel very stressed and overwhelmed with the volume of their work” (14-QC). However, efforts around education and promotion, while tentative, have emerged.

Table 5.

Efforts Mentioned by Health Professionals Being Undertaken to Improve Living Donor Kidney Transplantation.

| Rate of living donor kidney transplantation (province) | Low (Québec) |

Moderate (Ontario) |

High (British Columbia) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational sessions (12-QC and 03-QC) Informal promotion (03-QC) |

Standardized provincial referral (04-ON and 16-ON) Novel model of early referral with limited workup (16-ON) Targeted education interventions and community outreach (16-ON) Online resources (04-ON) Transplant seminars (04-ON and 15-ON) Transplant ambassadors (16-ON) Communication coordinators (15-ON) Communication protocols (16-ON) |

Frontline personnel with specific role descriptions (05-BC) Continued education of the frontline staff (05-BC and 06-BC) Informal promotion (06-BC) Transplant sessions (06-BC) Online resources (06-BC and 01-BC) Donor support (01-BC) Communication coordinators (06-BC) Communication protocols (16-ON) |

Discussion

In this qualitative analysis, we have identified several themes that HPs perceive as barriers to discussion about LDKT. These include lack of communication between treating teams, absence of referral guidelines, lack of multidisciplinary involvement, poor role perception of frontline staff, and lack of information and training leading to discomfort. One concerning theme pertaining to poor attitudes of some referring centers toward LDKT also emerged. A final theme pertained to HP’s perception of several patient-level barriers, which renders discussions about LDKT challenging.

Previous work has examined system- and center-level barriers to LDKT on a macroscopic level and predominantly in the United States.56,76-78 Three studies have asked physician’s input on this subject42,55,57; of these, only one was a qualitative study.42 By including other members of the team involved in transplant referral and coordination in our study, we have identified some important and modifiable barriers. The first 4 themes are easily modifiable. There are several ways to increase communication between treating teams and education of those involved in this process; some are outlined in Table 5. Centers ought to engage the entire multidisciplinary team in early discussions with patients related to LDKT. This will empower all HPs, improve their role perception, and enhance their knowledge, skills, and competencies.34,42,50,51 This is being done quite effectively in BC. Standardizing the referral process is a bit challenging as there is considerable amount of heterogeneity in the ideologies and preferences of centers and physicians.42,79,80 It is known that even when policies are created, transplant professionals will deviate.79 However, some level of standardization should be implemented to guide referring centers.

The last 2 identified themes merit further discussion. HPs poor attitudes toward LDKT are likely compounded by their beliefs and recent literature of increased long-term medical risks post donation.81 Hindsight bias after witnessing poor outcomes in some patients may contribute to this barrier.82 Some have suggested that hindsight bias can be alleviated using the adaptive learning approach, continuously updating knowledge structures and prospectively experiencing the success of LDKT in different types of individuals.82 Last, the propensity of the HP to locate the problem with the patient is a universally described barrier in the field of transplantation.36,42,43,48,52,54-56 This contributes to disparities and inequities in LDKT among vulnerable groups of patients and this theme was identified even by participants from ON and BC. Measures to address these are needed to ensure equity in LDKT.

The biggest strength of our study was that we conducted it in 3 different provinces of Canada with variable rates of LDKT and included the input of key frontline personnel that has not been previously captured. We identified that HPs perceive barriers to LDKT discussion even in regions with high rates of LDKT. The qualitative approach adopted in this study enabled a detailed and granular examination of HPs’ opinions compared with that offered by a quantitative approach. We used robust methodology and the interviews were conducted by a senior qualitative researcher with limited background in transplantation reducing the potential for moderator bias. The following limitations, however, need to be acknowledged. Our analysis may not be applicable to all provinces; although, QC, ON, and BC together comprise 75% of Canada’s population, and performance in these provinces significantly influences the country’s overall transplant results.4 Our study may be limited by social desirability and selection bias. It is likely that only those interested in LDKT would have agreed to participate. We did not pilot test the interview; however, after encountering problems with interviewing one participant, we made appropriate changes to the interview guide. It is possible that other relevant barriers considered unfit to the framework were inadvertently missed out. We did not perform member-checking, although this has been criticized for jeopardizing the internal validity of the study given the risk of participants changing their perspective following the interview.83,84

Despite this, our findings are relevant and have important implications for policy makers and organ procurement organizations in Canada. There is poor understanding of what HPs perceive as barriers and lack of evidence to ensure they are alleviated. We note predominance of these barriers in the province with the lowest rates of LDKT and likely directly contributing to this imbalance, although a quantitative study is indicated and is our next step. We believe that quantifying these themes will inform targeted and effective interventions to address barriers to LDKT at the level of the HP, and perhaps the health-delivery systems as well.

In conclusion, we have identified 6 important themes that HPs perceive as barriers to LDKT discussion with their patients. These themes were noted across 3 different provinces in Canada at variable rates, with differential efforts implemented to address them that appear to correlate with the rates of LDKT in the respective province. HPs involved with the referral and coordination of transplantation play a major role in access to LDKT. They have unique challenges that warrant further assessment and research to inform policy change and interventions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Appendix_1_Codebook-LDKT for Health Professional–Identified Barriers to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Qualitative Study by Shaifali Sandal, Kathleen Charlebois, Julio F. Fiore, David Kenneth Wright, Marie-Chantal Fortin, Liane S. Feldman, Ahsan Alam and Catherine Weber in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the 16 individuals who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study was approved by the local institutional review board (McGill University Health Center Research Ethics Board and the CIUSSS-OMTL).

Consent for Publication: All authors reviewed the final manuscript and provided consent for publication.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data and materials may be made available upon written request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions: Sandal: Involved in study conception and design, analyzed and interpreted data; drafted and revised the article; provided intellectual content of critical importance; and approved the final version. Charlebois: Involved in study design, conducted the interviews, analyzed and interpreted data; drafted and revised the article; provided intellectual content of critical importance; and approved the final version. Fiore: Involved in study design, analyzed and interpreted data; revised the article; provided intellectual content of critical importance; and approved the final version. Wright: Involved in study design; revised the article; provided intellectual content of critical importance; and approved the final version. Fortin: Analyzed and interpreted data; revised the article; provided intellectual content of critical importance; and approved the final version. Feldman, Alam, and Weber: Involved in study conception and design; revised the article; provided intellectual content of critical importance; and approved the final version. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported using an education grant from Amgen Canada to promote efforts to increase living donor kidney transplantation. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, writing, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Shaifali Sandal  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1941-0598

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1941-0598

References

- 1. Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2013 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(suppl 2):1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United States Renal Data System. USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canadian organ replacement register annual statistics, 2007 to 2016 Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-organ-replacement-register-2016. Published 2018. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- 4. Canadian Blood Services. Organ donation and transplantation in Canada, system progress report 2006–2015. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Blood Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manera KE, Hanson CS, Chapman JR, et al. Expectations and experiences of follow-up and self-care after living kidney donation: a focus group study. Transplantation. 2017;101(10):2627-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(supp l):121-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC, et al. Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):953-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim SJ, Fenton SS, Kappel J, et al. Organ donation and transplantation in Canada: insights from the Canadian Organ Replacement Register. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2014;1:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gill JS, Klarenbach S, Cole E, Shemie SD. Deceased organ donation in Canada: an opportunity to heal a fractured system. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(8):1580-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giles S. An antidote to the emerging two tier organ donation policy in Canada: the Public Cadaveric Organ Donation Program. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(4):188-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Getchell LE, McKenzie SQ, Sontrop JM, Hayward JS, McCallum MK, Garg AX. Increasing the rate of living donor kidney transplantation in Ontario: donor- and recipient-identified barriers and solutions. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:1-8. doi: 10.1177/2054358117698666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Norris S. Organ donation and transplantation in Canada 2018. http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.856553/publication.html. Published 2018.

- 13. Tan JC, Gordon EJ, Dew MA, et al. Living donor kidney transplantation: facilitating education about live kidney donation—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1670-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waterman AD, Morgievich M, Cohen DJ, et al. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving education outside of transplant centers about live donor transplantation—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1659-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moore DR, Serur D, Rudow DL, Rodrigue JR, Hays R, Cooper M. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving efficiencies in live kidney donor evaluation—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1678-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodrigue JR, Kazley AS, Mandelbrot DA, Hays R, LaPointe Rudow D, Baliga P. Living donor kidney transplantation: overcoming disparities in live kidney donation in the US—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1687-1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tushla L, Rudow DL, Milton J, Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Hays R. Living-donor kidney transplantation: reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation—recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1696-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klarenbach S, Barnieh L, Gill J. Is living kidney donation the answer to the economic problem of end-stage renal disease? Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(5):533-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kranenburg LW, Zuidema WC, Weimar W, et al. Psychological barriers for living kidney donation: how to inform the potential donors? Transplantation. 2007;84(8):965-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barnieh L, McLaughlin K, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, Yilmaz S, Hemmelgarn BR. Barriers to living kidney donation identified by eligible candidates with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(2):732-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gillespie A, Hammer H, Bass SB, et al. Attitudes towards living donor kidney transplantation among urban African American hemodialysis patients: a qualitative and quantitative analysis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):852-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. Patients’ willingness to talk to others about living kidney donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, et al. Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):476-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ismail SY, Claassens L, Luchtenburg AE, et al. Living donor kidney transplantation among ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: a model for breaking the hurdles. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(1):118-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kranenburg LW, Richards M, Zuidema WC, et al. Avoiding the issue: patients’ (non)communication with potential living kidney donors. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(1):39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garonzik-Wang JM, Berger JC, Ros RL, et al. Live donor champion: finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation. 2012;93(11):1147-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sandal SDN, Wang S, Guadagno E, Ekmekjian T, Alam A. Efficacy of Educational Interventions in Improving Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Transplantation. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barnieh L, Collister D, Manns B, et al. A scoping review for strategies to increase living kidney donation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(9):1518-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elman A, Wright L, Zaltzman JS. Public solicitation for organ donors: a time for direction in Canada. CMAJ. 2016;188(7):487-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grace BS, Clayton PA, Cass A, McDonald SP. Transplantation rates for living-but not deceased-donor kidneys vary with socioeconomic status in Australia. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):138-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Transplantation workshop report. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/44027.html. Published 2011. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- 33. Headley CM. Do you know how to respond to questions related to kidney donation? Nephrol Nurs J. 2014;41(6):618-623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Goalby CJ, Dinkel KM, Xiao H, Lentine KL. Assessing transplant education practices in dialysis centers: comparing educator reported and Medicare data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1617-1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL. Optimal transplant education for recipients to increase pursuit of living donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boulware LE, Meoni LA, Fink NE, et al. Preferences, knowledge, communication and patient-physician discussion of living kidney transplantation in African American families. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(6):1503-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weng FL, Mange KC. A comparison of persons who present for preemptive and nonpreemptive kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):1050-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Johansen KL. Impact of race on predialysis discussions and kidney transplant preemptive wait-listing. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(4):305-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kutner NG, Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Amaral S. Perspectives on the new kidney disease education benefit: early awareness, race and kidney transplant access in a USRDS study. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(4):1017-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morton RL, Howard K, Webster AC, Snelling P. Patient INformation about Options for Treatment (PINOT): a prospective national study of information given to incident CKD Stage 5 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(4):1266-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waterman AD, Robbins ML, Paiva AL, et al. Measuring kidney patients’ motivation to pursue living donor kidney transplant: development of stage of change, decisional balance and self-efficacy measures. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(2):210-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hanson CS, Chadban SJ, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Wong G, Tong A. Nephrologists’ perspectives on recipient eligibility and access to living kidney donor transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100(4):943-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, David-Kasdan JA, Epstein AM. Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(2):350-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mucsi I, Bansal A, Famure O, et al. Ethnic background is a potential barrier to living donor kidney transplantation in Canada: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2017;101(4):e142-e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anderson K, Devitt J, Cunningham J, Preece C, Jardine M, Cass A. If you can’t comply with dialysis, how do you expect me to trust you with transplantation? Australian nephrologists’ views on indigenous Australians’ “non-compliance” and their suitability for kidney transplantation. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tong A, Hanson CS, Chapman JR, et al. The preferences and perspectives of nephrologists on patients’ access to kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Transplantation. 2014;98(7):682-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Waterman A, Peipert J, Xiao H, Goalby C, Lentine K. Educational strategies for increased wait-listing rates: opportunities for dialysis center intervention. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:239.27421969 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Anderson K, Yeates K, Cunningham J, Devitt J, Cass A. They really want to go back home, they hate it here: the importance of place in Canadian health professionals’ views on the barriers facing Aboriginal patients accessing kidney transplants. Health Place. 2009;15(1):390-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Balhara KS, Kucirka LM, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant education by profit status of the dialysis center. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(11):3104-3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jawoniyi O, Gormley K, McGleenan E, Noble HR. Organ donation and transplantation: awareness and roles of healthcare professionals—a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(5-6):e726-e738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ghahramani N, Sanati-Mehrizy A, Wang C. Perceptions of patient candidacy for kidney transplant in the United States: a qualitative study comparing rural and urban nephrologists. Exp Clin Transplant. 2014;12(1):9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Navaneethan SD, Singh S. A systematic review of barriers in access to renal transplantation among African Americans in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(6):769-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pradel FG, Jain R, Mullins CD, Vassalotti JA, Bartlett ST. A survey of nephrologists’ views on preemptive transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1837-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Beasley CL, Hull AR, Rosenthal JT. Living kidney donation: a survey of professional attitudes and practices. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30(4):549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19(4):244-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cunningham J, Cass A, Anderson K, et al. Australian nephrologists’ attitudes towards living kidney donation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(5):1178-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Salter ML, Orandi B, McAdams-DeMarco MA, et al. Patient- and provider-reported information about transplantation and subsequent waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(12):2871-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Meth. 2004;3(1):1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hunt MR. Strengths and challenges in the use of interpretive description: reflections arising from a study of the moral experience of health professionals in humanitarian work. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(9):1284-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thorne S. Interpretive Description. New York: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Banning M. A review of clinical decision making: models and current research. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(2):187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. O’Neill ES, Dluhy NM, Chin E. Modelling novice clinical reasoning for a computerized decision support system. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(1):68-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. O’Neill ES, Dluhy NM, Fortier PJ, Michel HE. Knowledge acquisition, synthesis, and validation: a model for decision support systems. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(2):134-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Robinson OC. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual Res Psychol. 2013;11(1):25-41. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vaismoradi M, Jones J, Turunen H, Snelgrove S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016;6(5):100-110. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Timmermans S, Tavory I. Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociol Theor. 2012;30(3):167-186. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Braun V, Clarke V, Rance N. How to use thematic analysis with interview data (process research). In: Vossler A, Moller N. eds. The Counselling and Psychotherapy Research Handbook. London, England: Sage; 2014:183-197. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Res Nurs. 2008;13(1):68-75. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guest G. How many interviews are enough? an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method. 2006;18(1):59-82. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kerr C. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharm Out. 2010;10(3):269-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health C. 2007;19(6):349-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lowrie M. Angry Quebec nurses push for lower patient ratios, less overtime. The Canadian Press. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/angry-quebec-nurses-push-for-lower-patient-ratios-less-overtime-1.3808670. Published February 18, 2018.

- 76. Reese PP, Feldman HI, Bloom RD, et al. Assessment of variation in live donor kidney transplantation across transplant centers in the United States. Transplantation. 2011;91(12):1357-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hall EC, James NT, Garonzik Wang JM, et al. Center-level factors and racial disparities in living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(6):849-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Udayaraj U, Ben-Shlomo Y, Roderick P, et al. Social deprivation, ethnicity, and uptake of living kidney donor transplantation in the United Kingdom. Transplantation. 2012;93(6):610-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lafranca JA, Spoon EQW, van de, Wetering J, IJzermans JNM, Dor F. Attitudes among transplant professionals regarding shifting paradigms in eligibility criteria for live kidney donation. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Reese PP, Feldman HI, McBride MA, Anderson K, Asch DA, Bloom RD. Substantial variation in the acceptance of medically complex live kidney donors across US renal transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(10):2062-2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lam NN, Lentine KL, Levey AS, Kasiske BL, Garg AX. Long-term medical risks to the living kidney donor. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(7):411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Henriksen K, Kaplan H. Hindsight bias, outcome knowledge and adaptive learning. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(suppl 2):ii46-ii50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Goldblatt H, Karnieli-Miller O, Neumann M. Sharing qualitative research findings with participants: study experiences of methodological and ethical dilemmas. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(3):389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. Adv Nurs Sci. 1993;16(2):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Appendix_1_Codebook-LDKT for Health Professional–Identified Barriers to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Qualitative Study by Shaifali Sandal, Kathleen Charlebois, Julio F. Fiore, David Kenneth Wright, Marie-Chantal Fortin, Liane S. Feldman, Ahsan Alam and Catherine Weber in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease