Abstract

Metabolic acidosis is considered deleterious but is common in post-surgical patients admitted to intensive care unit. We evaluated the prevalence and time course of metabolic acidosis in elective major surgery, and generated hypotheses about causes, by hourly arterial blood sampling in 92 patients. Metabolic acidosis began before incision and most had occurred by the next hour. Seventy-eight per cent of patients had a significant metabolic acidosis post-operatively. Two overlapping phases were observed. The early phase started before incision, characterised by a rising chloride and falling anion gap, unrelated to saline use. The late phase was partly associated with lactate, related to surgery type, and early fluids appeared protective. There was a trend towards longer intensive care unit (+1.3 days) and hospital (+3.2 days) stay with metabolic acidosis. This is the first large study of the evolution of this common finding, demonstrating a pre-incision component. The early phase appears unavoidable or unpredictable, but the late phase might be modified by early fluid administration. It remains unclear whether acidosis of this type should be avoided.

Keywords: Acid–base, acidosis, anaesthesia, fluid, surgery

Introduction

In health, the extracellular fluid hydrogen ion concentration is tightly controlled. Increases, particularly those due to metabolic causes, are therefore likely to represent significant homeostatic derangement and also to be potentially harmful. Accordingly perioperative metabolic acidosis (MA) is of concern to the anaesthetist. Although post-operative MA has been recognised for over a century, it remains poorly studied.1,2

A recent study reported a 58.1% prevalence of significant post-operative MA (standard base excess (SBE) <−2 mEq l−1).3 However, the authors did not investigate the evolution of the acidosis. Other studies are too small to estimate the prevalence of acidosis, but invariably report that it occurs.1,4,5 There is some evidence that perioperative MA is associated with poor outcomes.3

This study first aims to define the prevalence of MA in elective major surgery and to examine the time course of its development. Second, it aims to generate hypotheses as to the causes and examine whether a MA is associated with poorer outcomes.

Methods

Ethical approval was granted by the Bradford Research Ethics Committee (07/H1302/63).

We conducted a prospective single-centre observational study in a 1100 bed teaching hospital. We recruited adult patients undergoing elective major surgery requiring intra-arterial pressure monitoring and post-operative intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Between November 2008 and February 2012, we assessed a convenience sample of 101 patients for inclusion in the study. Of these, 92 provided written informed consent to take part and all were included.

We sampled arterial blood with the patient awake, at skin incision, and every hour subsequently. Samples were also taken on admission to the ICU, and 12 hourly thereafter until the arterial catheter was removed. Blood samples were analysed using a Cobas B221 device. The anaesthetist was blinded to the results of blood gas analysis, except on request for clinical purposes, and as a purely observational study all treatment was left to the discretion of the anaesthetist as per their normal practice. Simultaneously we recorded blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, CVP (if available), tidal volume, respiratory pressures, respiratory rate, end-tidal CO2, and the administration of fluids and drugs. Surgery was classified into three groups: body surface (mainly head and neck cancer resection), open intracavity (upper and lower gastrointestinal resection and aortic surgery), and laparoscopic (gastrointestinal resection).

We used SBE as the main indicator of MA.6,7 In order to help elucidate the cause of any acidosis, we calculated the strong ion difference (SID) as [Na+] + [K+] − [Cl−] − [lactate−]. We also calculated the anion gap (AG), as [Na+] + [K+] − [Cl−] − [HCO3−].

We analysed data using Stata 11.2 (StataCorp, 2009). The primary outcome variable was the prevalence of significant acidosis at each measured time point, defined as a SBE below −2 mEq l−1. Secondary outcome variables were the values of pH, SBE, CO2, SID, AG and relevant anions such as lactate, at each measured point during the follow-up period. For comparisons between time points, data were tested for a normal distribution and a paired Student’s t-test was performed. Clinical outcome was compared using ICU and hospital length of stay and mortality.

We estimated using worst-case figures (a prevalence of 50%) that a sample size of 96 patients would give a 95% probability of being within 10% of the true value for the primary outcome. For the secondary outcomes, our analyser is accurate to approximately ±1% for each variable. With 96 patients the standard error of the mean at each time point would therefore be accurate to approximately ±0.1%.

We created the hypothesis-generating regression models to explain acidosis occurrence by starting with a model including all variables of interest, and using a manual backwards stepwise regression approach whilst monitoring the adjusted R2. We produced a final model for comparison using only the selected variables, to check that the coefficients were similar to the initial model. Factors included were the volumes of different types of fluid given in the pre-incision period, the rates of each type of fluid given intraoperatively, the use of vasopressors and blood pressure drop pre-incision, time between induction and incision, surgery type and duration, patient age, anaesthetic agent, and CO2 change. We used fluid rates post-incision rather than absolute volumes for the analysis because of collinearity between surgery length and absolute volume of fluid received.

Results

Ninety-two patients were recruited during the study period – their characteristics are given in Table 1. Two patients are missing initial blood gas data and were excluded from the results. There were three deaths. The main fluid used was Hartmann’s solution, with some starch and gelatine use which was standard practice at the time. 0.9% saline, where used, tended to be continued from the ward or used either side of blood administration.

Table 1.

Patient and operation characteristics.

| Age | Mean 67.5 (±9.8 SD, range 39–88) | |

| Sex | 70% male (63/90 patients) | |

| Comorbidities | Heart disease 48% (43/90), diabetes 10% (9/90) | |

| Follow-up in surgery | Median 4 h (IQR 2–5) | |

| Surgery type | Open: 71 (79%) • Major vascular 21 • Open oesophagectomy 21 • Urological resection 19 • GI resection 10 Laparoscopic/thoracoscopic: 12 (13%) • GI resection 10 • Minimally invasive oesophagectomy 2 Body surface: 7 (8%) • Head and neck resections 5 • Vascular 2 | |

| Anaesthesia maintenance | Volatile: 100% – Desflurane 86 (96%) – Sevoflurane 4 (4%) Remifentanil: 42 (47%) | |

| Fluids (mean values) | Pre-incision Hartmann’s 310 ml 0.9% saline 140 ml Volulyte 120 ml Gelofusine 20 ml | Post-incision Hartmann’s 1270 ml Volulyte 500 ml Gelofusine 310 ml Blood 170 ml 0.9% saline 120 ml Voluven 110 ml |

| Critical care length of stay | Median two days (range 1–24, IQR 1–4) | |

| Hospital length of stay | Median 14 days (range 3–74, IQR 10–19) | |

IQR: interquartile range.

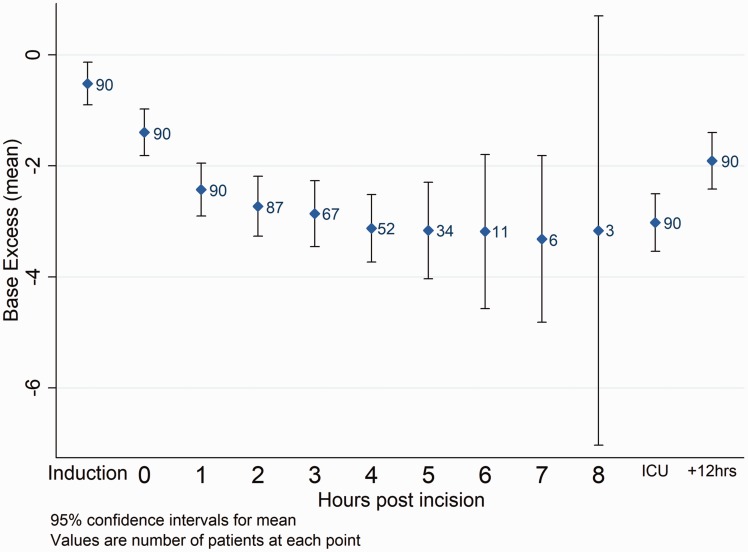

By the end of surgery 70 patients (78%) had a significant MA (SBE <−2 mEq l−1); in 37 patients (41%) the SBE was below −4 mEq l−1. The prevalence rose during the course of surgery (Table 2, Figure 1), but notably 32 patients (36%) already had a significant MA at incision, a mean of 55 min after the induction. Table 3 gives secondary outcome measures.

Table 2.

Proportion of significant metabolic acidosis (SBE < −2 mEQ l−1) across time.

| Time point | SBE < −2 mEq l−1 | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Start (awake) | 17% | 9–25% |

| Incision | 36% | 25–46% |

| 1 h post-incision | 57% | 46–67% |

| End of surgery | 78% | 69–87% |

| Arrival on ICU | 67% | 57–77% |

| 12 h post | 42% | 32–53% |

ICU: intensive care unit; SBE: standard base excess.

Figure 1.

Mean SBE across time with 95% confidence intervals. ICU: intensive care unit.

Table 3.

Pattern of acidosis during surgery (*p < 0.05, #p < 0.005, **p < 0.0005 versus previous).

| Start | Incision | 1 h | End of surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.42 | 7.40** | 7.36** | 7.35* |

| SBE (mEq l−1) | −0.5 | −1.4** | −2.4** | −3.4** |

| Sodium (mmol l−1) | 139.5 | 139.5 | 138.7 | 138.2* |

| Potassium (mmol l−1) | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.9# | 4.2** |

| Chloride (mmol l−1) | 100.7 | 102.1** | 102.4 | 103.1# |

| Bicarbonate (mmol l−1) | 23.8 | 23.4* | 22.9* | 22.1** |

| Lactate (mmol l−1) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.0** |

| CO2 (kPa) | 5.0 | 5.2* | 5.5* | 5.5 |

| SID (mEq l−1) | 41.4 | 39.8** | 38.6** | 37.1** |

| AG (mEq l−1) | 18.8 | 17.8** | 17.2 | 17.2 |

AG: anion gap; SBE: standard base excess; SID: strong ion difference.

Regression analysis

As a result of the findings, we split the hypothesis-generating regression analysis into two phases: pre- and post-incision.

Pre-incision

In the pre-incision analysis, no measured factor was a significant predictor of the change in SBE; the adjusted R2 for the model was 0.04 (unadjusted 0.24) – pre-incision acidosis development did not appear to depend on any of the factors measured. It appears that this pre-incision acidosis is either unavoidable with the anaesthetic techniques used in this study, unpredictable, or related to unmeasured factors.

To investigate whether the acidosis seen pre-incision was related to fluids infused, post hoc subgroups were defined by whether or not the patient had received any unbalanced fluids (predominantly saline) pre-incision. Most changes were similar between the two groups; the base excess dropped slightly more in the unbalanced group but this difference was not statistically significant (change of −1.1 mEq l−1 versus −0.7 mEq l−1, p = 0.09). The measured bicarbonate dropped more in the unbalanced group, reaching statistical significance but the difference between groups was small (change of −0.6 mEq l−1 versus −0.3 mEq l−1, p = 0.02).

Post-incision

The regression model for post-incision acidosis fits much better, with an adjusted R2 of 0.50 (unadjusted 0.64). The main predictors are listed in Table 4. The adjusted R2 of a model including only these factors was 0.51 (unadjusted 0.55). Surgery length was non-significantly correlated with a decreased acidosis possibly due to the tendency for the less invasive body surface operations to be the longest.

Table 4.

Main predictors of post-incision metabolic acidosis (values from final model).

| Predicted change in SBE (mEq l−1) | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartmann’s pre-incision | +1 per 790 ml | 460–2870 ml | 0.007 |

| Saline pre-incision | +1 per 510 ml | 300–1660 ml | 0.005 |

| Volulyte pre-incision | +1 per 260 ml | 190–400 ml | <0.001 |

| Surgery type (versus open) | |||

| – Laparoscopic/Thoracoscopic | +1.4 | 0.6–2.2 mEq l−1 | 0.001 |

| – Body surface | +1.3 | 0.4–2.3 mEq l−1 | 0.006 |

| Blood rate post-incision | −1 per 130 ml/h | 100–200 ml/h | <0.001 |

| Gelofusine rate post-incision | −1 per 410 ml/h | 250–1210 ml/h | 0.003 |

| CO2 change post-incision | +0.28 per 1 kPa rise | 0.01 to + 0.54 per 1 kPa | 0.04 |

SBE: standard base excess.

After surgery

Intensive care admission and 12 h SBE are given in Table 2. At 24 h the prevalence of significant MA was 34% of the 50 patients who still had arterial monitoring in place, although less acidotic patients were more likely to have arterial catheters removed, skewing this finding.

We also tested the effect of the presence of a significant MA at the end of surgery on ICU and hospital length of stay. Given our relatively small numbers it was not surprising that neither effect was statistically significant, but a regression model controlling for patient age, surgery type, and surgery length suggested a trend for both longer ICU stay (1.3 days extra, 95%CI 2.8 days extra to 0.2 days shorter) and longer hospital stay (3.2 days longer, 95%CI 8.9 days longer to 2.6 days shorter).

Discussion

Our data confirm the high prevalence of MA after major surgery; 78% of patients had a significant MA post-operatively. However, the findings that this had already occurred in 36% of patients by the time of incision, and the time course of its evolution, are previously unreported. The magnitude of the post-operative acidosis (SBE −3.4 mEq l−1) is in line with previous studies.1,3

Our initial theory was that perioperative MA would be a ‘lactic acidosis’ (i.e. accompanied by rising lactate), due to the neurohumoral ‘stress response’ to surgery with several putative mechanisms. First, increased circulating catecholamines drive glycolysis to produce pyruvate, but because the Krebs mechanism is swamped, it is shunted to lactate. Second, redistribution of blood flow (e.g. away from the gut) may result in regional hypoperfusion, resulting in anaerobic glycolysis and lactic acidosis.Third, fluid loss may result in hypovolaemia and hypoperfusion. Fourth, the inflammatory response may itself directly affect cellular energetics (e.g. the downregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by TNFα) to inhibit ATP production. Thus, we expected the acidosis to follow incision and be related to the magnitude of the surgery. Whilst we did see the latter effect, only around quarter of the acidosis was accompanied by lactate. However, the most surprising finding was that the acidosis develops prior to incision. Our hypothesis therefore is that the acidosis has two phases and causes, outlined below.

Pre-incision

Seventeen per cent of patients were acidotic prior to the induction of anaesthesia. This was possibly due to pre-operative fasting, with a contribution from 0.9% saline8 where it was used as a maintenance fluid on the ward; however, we lack the data to make further interpretation.

Unexpectedly, the mean SBE dropped by 0.9 mEq l−1 between the induction of anaesthesia and incision. Whilst this was associated with a 1.4 mmol/l rise in serum chloride, it is not clear that 0.9% saline administration was to blame as the acidosis was still seen when only balanced fluids had been given pre-incision. Also, the regression analysis found no significant effect of fluid type or volume on the pre-incision acidosis. The fall in SID more than accounts for the change in SBE, and the AG falls rather than rises, suggesting that unmeasured anions (e.g. administered drugs) are not significant causes. The Hamburger phenomenon also appears to be unlikely as there is an increase in the PaCO2 rather than a decrease.

Desflurane, which was used for the maintenance of anaesthesia in most patients, has been shown to produce a MA in healthy volunteers not undergoing surgery, of a similar magnitude to that found pre-incision in this study.9 Acidosis has also been reported for other volatile agents in humans10 and animals.11 It seems likely that this is responsible for much of the acidosis seen pre-incision in this study; the mechanism is unclear except that it does not appear to involve unmeasured anions. Some older evidence points to an expansion of fluid in the extracellular space at induction with general anaesthetics, which could lead to a dilutional acidosis without the need to blame 0.9% saline. Whilst these studies used older anaesthetic agents, the effect was present with both intravenous12 and inhalational13 agents – suggesting it is related to anaesthesia itself rather than a specific drug. As most cells contain relatively little chloride, the observed rise in chloride concentration is more difficult to explain if ECF expansion from intracellular fluid is the cause, although erythrocytes contain more than most cells (approx 90 mmol l−1).14

Post-incision

The acidosis continued to develop after the start of surgery though mostly in the first hour. The AG and SID fell, suggesting that the acidosis continued to involve only measured ions. The rise in chloride was insufficient for hyperchloraemia from fluid administration to be a major cause;8 however, fluid shift from the intracellular to extracellular space appears to continue for several hours after the induction of anaesthesia.12 The small rise in lactate suggests the acidosis which accompanies lactate production may have a contributory role, but insufficient on its own to explain the change in SBE seen.

The post-incision regression model fits the data well (adjusted R2 0.51), although this was produced from the entire cohort and not validated separately. The appearance of surgery type was not surprising though the numbers were too small to determine any difference between laparoscopic and body surface surgery; it seems plausible that open-cavity surgery would result in the greatest metabolic disturbance. The lack of effect of operation length, in contrast to previous data,3 may reflect the more varied types of surgery in this study, particularly the fact that the longest operations tended to be relatively less invasive maxillofacial operations.

The main predictors of MA after surgery type appear to relate to fluid administration. Fluid given prior to incision appears to protect against acidosis, even if the fluid is saline which is known to cause an acidosis itself in large quantities.8,15 The protective effect seems most likely to relate to volume expansion, especially given the ratios of the volumes required to protect against a 1 mmol/l fall in BXS which match the experimentally determined ratios of volume retention at 6 h in volunteer studies.16,17

Other than Hartmann’s solution, fluid given later on seems to predict a worse acidosis – although this was only statistically significant for gelofusine and blood. Acidosis from saline administration might be explained as hyperchloraemic in origin,8,18 but blood and gelofusine would not be expected to cause this.17 Blood and colloid administration may merely be a marker for increased blood loss, hypotension, or more invasive surgery. However, vasopressor use did not appear in the final model, which seems counter to this.

Apart from fluids and surgery type, the only other significant predictor of acidosis was a change in arterial pCO2. A 1 kPa rise in pCO2 predicted an increase in SBE of 0.27 mEq l−1. Whilst it is not impossible that the causation is in the opposite direction, we assumed that the pCO2 was under the control of the treating anaesthetist – albeit generally by reference to end-tidal pCO2 which may start to gradually under-represent the arterial pCO2 under anaesthesia.19 In addition, if the acidosis were causing the change in pCO2, a rise in pCO2 would be expected due to the liberation of carbon dioxide from bicarbonate; our study found the correlation to be in the opposite direction. The effect may result from changes in cell membrane ion transport (intracellular buffering)20 or may represent the early stages of renal compensation which can be observed over time periods as short as an hour despite taking longer to fully oppose the pH change.21

Effects on outcome

Whilst there was no statistically significant effect demonstrated of acidosis on ICU or hospital stay, there was a trend towards a clinically significant increase. The estimates are similar to other work.3 However, it is unclear whether this represents an effect which could be modified by preventing the acidosis, or merely that the acidosis is a marker for patients with poor exercise tolerance or undergoing the most major surgery.

The vast majority of patients in this study survived to hospital discharge; it is not possible to draw meaningful conclusions from the acid/base status of the three who died.

Methodological quality

This study was intended to evaluate the prevalence and time course of acidosis in surgery and to act as a hypothesis-generating tool to investigate possible causes. This is the first study which examines the time course of MA in such a large sample of patients. As in other studies,1,3 the majority of patients were having open-cavity surgery where acidosis might be expected to be more common. The inclusion of body surface procedures acted as something of a control group, demonstrating that it is not just surgery traditionally regarded as high risk which can produce this phenomenon. The patient sample is fairly typical for elective admissions to critical care in a large UK hospital.

Whilst hourly per operative sampling is novel, we only measured parameters available on a standard analyser. Measurement of other charged particles such as plasma proteins and Krebs cycle intermediates may be useful. Assessment of the plasma and extracellular volume would also have been useful, albeit very difficult to measure on an hourly basis.

The post-incision regression model has a high coefficient of determination, suggesting that the measured predictors explain just over half of the variation in acidosis. However, the pre-incision regression model explained almost none of the early acidosis. It may be that further unmeasured predictors would have helped such as patient comorbidities or it could be that the study sample was too homogeneous. Given the possibility that the acidosis was caused by the use of volatile anaesthetic agents (particularly desflurane9), the fact that all patients received either sevoflurane or desflurane as maintenance anaesthesia means that the study was unable to examine this factor. Additionally, as all patients in this study were necessarily ‘higher risk’ patients in whom an arterial line was being placed for their surgery, it would be extrapolation to assume this acidosis occurs in all anaesthesia, and further study on patients not bound for critical care would be enlightening.

Whilst the post-incision model is a good match for the observed acidosis, it cannot distinguish correlation from causation. Given that the main predictors relate to fluid administration it would be useful to know the reasons behind the choice of a specific fluid to help differentiate acid–base changes caused by the fluid from those caused by the event prompting fluid administration. Protocolised or even randomised fluid administration may help further, as well as helping to elucidate why the effects of hyperchloraemic acidosis15 from saline did not appear to be significant in this study.

Conclusion

Significant MA at the end of major surgery has a high prevalence (78%). However, rather than being purely a product of time and surgical disturbance, it appears that the acidosis starts at the induction of anaesthesia and most of it has already occurred by the first hour post-incision. These are novel findings.

The acidosis appears to occur in two overlapping phases. The first starts at the induction of anaesthesia and is characterised by a rise in chloride and a fall in the AG, so does not appear related to lactate or other unmeasured anions from tissue hypoxia. At least in the context of this study, it appears to be unavoidable – though this could also be a product of homogeneity in anaesthetic technique, or unmeasured predictor variables.

The second phase is much slower and is characterised by a rise in lactate, although a traditional lactic acidosis does not fully explain the acidosis. The rise in chloride seen may relate to this second phase or could be a continuation of the first phase. However, in this study there is evidence to suggest that the magnitude of the acidosis in the second phase is affected by pre-incision volume loading. Despite evidence that 0.9% saline causes a hyperchloraemic acidosis in large volumes, this study suggests that in the volumes used it had a protective effect along with Hartmann’s solution and Volulyte, roughly in proportion with their 6 h volume retention. The second phase also seems to be influenced by ‘surgical stress’ both in terms of surgery type and surrogate markers for blood loss, i.e. the intraoperative infusion of blood and colloids. Lastly, this phase appears to involve an element of compensation for changes in carbon dioxide which is probably the start of renal compensation.

Whilst common, it is less clear from this study that the acidosis is deleterious. Whilst there was a trend towards increased ICU and hospital stay which agrees with previous data,3 this may merely represent stratification of more complicated surgery beyond the three main groups of surgery type; or patients with a poorer premorbid state may be more prone to acidosis and also require more time in ICU and hospital. Our results do not give a clear indication that MA of the type seen in this study is necessarily to be avoided.22

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with gratitude, the help of the following in the conduct of this study, Ben Booth, Andrew Brennan, David Craske, Richard Davidson, Nicola Ellis, Anthony Hughes.

Author’s contribution

TOL: data analysis, data modelling, writing up first draft, and subsequent revisions of the paper

AQ: study design, patient recruitment, review of paper

SJF: study design, patient recruitment, revisions to paper

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

References

- 1.Waters JH, Miller LR, Clack S, et al. Cause of metabolic acidosis in prolonged surgery. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 2142–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RD. Post-operative acidosis. Proc R Soc Med 1929; 22: 747–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park C-M, Chun H-K, Jeon K, et al. Factors related to post-operative metabolic acidosis following major abdominal surgery. ANZ J Surg 2014; 84: 574–580. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bruegger D, Bauer A, Rehm M, et al. Effect of hypertonic saline dextran on acid-base balance in patients undergoing surgery of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi AYS, Ahmad NS, De Beer DA. Metabolic changes during major craniofacial surgery. Pediatr Anesth 2010; 20: 851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellum JA. Clinical review: reunification of acid–base physiology. Crit Care 2005; 9: 500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siggaard-Andersen O, Fogh-Andersen N. Base excess or buffer base (strong ion difference) as measure of a non-respiratory acid-base disturbance. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 1995; 107: 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheingraber S, Rehm M, Sehmisch C, et al. Rapid saline infusion produces hyperchloremic acidosis in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 1265–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiskopf RB, Cahalan MK, Eger EI, et al. Cardiovascular actions of desflurane in normocarbic volunteers. Anesth Analg 1991; 73: 143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baxter Healthcare. Sevoflurane: Product Information, 2006.

- 11.Sjöblom M, Nylander O. Isoflurane-induced acidosis depresses basal and PGE2-stimulated duodenal bicarbonate secretion in mice. Am J Physiol – Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007; 292: G899–G904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rampton DS, Ramsay DJ. The effects of pentobarbitone anaesthesia on the volume and composition of the extracellular fluid of dogs. J Physiol 1974; 237: 521–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford EJ, Gaudino M. Changes in extracellular fluid volume, renal function, and electrolyte excretion induced by intravenous saline solution and by short periods of anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1952; 13: 374–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Story D, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: chloride in critical illness. Crit Care 2010; 14: 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane C, Lee A. A comparison of plasmalyte 148 and 0.9% saline for intra-operative fluid replacement. Anaesthesia 1994; 49: 779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reid F, Lobo DN, Williams RN, et al. (Ab)normal saline and physiological Hartmann’s solution: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Clin Sci 2003; 104: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lobo DN, Stanga Z, Aloysius MM, et al. Effect of volume loading with 1 liter intravenous infusions of 0.9% saline, 4% succinylated gelatine (Gelofusine) and 6% hydroxyethyl starch (Voluven) on blood volume and endocrine responses: a randomized, three-way crossover study in healthy volunteers. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prough DS, Bidani A. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is a predictable consequence of intraoperative infusion of 0.9% saline. Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raemer DB, Francis D, Philip JH, et al. Variation in PCO2 between arterial blood and peak expired gas during anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1983; 62: 1065–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elkinton JR, Singer RB, Barker ES, et al. Effects in man of acute experimental respiratory alkalosis and acidosis on ionic transfers in the total body fluids. J Clin Invest 1955; 34: 1671–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yih Loong Lai, Martin ED, Attebery BA, et al. Mechanisms of extracellular pH adjustments in hypercapnia. Respir Physiol 1973; 19: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handy JM, Soni N. Physiological effects of hyperchloraemia and acidosis. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]