Abstract

Objectives

Baloxavir marboxil (formerly S-033188) is a first-in-class, orally available, cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor licensed in Japan and the USA for the treatment of influenza virus infection. We evaluated the efficacy of delayed oral treatment with baloxavir marboxil in combination with a neuraminidase inhibitor in a mouse model of lethal influenza virus infection.

Methods

The inhibitory potency of baloxavir acid (the active form of baloxavir marboxil) in combination with neuraminidase inhibitors was tested in vitro. The therapeutic effects of baloxavir marboxil and oseltamivir phosphate, or combinations thereof, were evaluated in mice lethally infected with influenza virus A/PR/8/34; treatments started 96 h post-infection.

Results

Combinations of baloxavir acid and neuraminidase inhibitor exhibited synergistic potency against viral replication by means of inhibition of cytopathic effects in vitro. In mice, baloxavir marboxil monotherapy (15 or 50 mg/kg twice daily) significantly and dose-dependently reduced virus titre 24 h after administration and completely prevented mortality, whereas oseltamivir phosphate treatments were not as effective. In this model, a suboptimal dose of baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) in combination with oseltamivir phosphate provided additional efficacy compared with monotherapy in terms of virus-induced mortality, elevation of cytokine/chemokine levels and pathological changes in the lung.

Conclusions

Baloxavir marboxil monotherapy with 96 h-delayed oral dosing achieved drastic reductions in virus titre, inflammatory response and mortality in a mouse model. Combination treatment with baloxavir acid and oseltamivir acid in vitro and baloxavir marboxil and oseltamivir phosphate in mice produced synergistic responses against influenza virus infections, suggesting that treating humans with the combination may be beneficial.

Introduction

The influenza virus envelope contains two major glycoproteins, haemagglutinin and neuraminidase; neuraminidase not only plays a critical role in the budding process but also takes part in the fusion and entry of virus into the host cells.1 Current antiviral treatment for influenza virus infections is dominated by a single class of antiviral drugs, the neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs).2 Although there is some evidence of resistance developing,3 clinical trials have shown NAIs to be generally effective against acute, uncomplicated influenza infection and they were able to significantly reduce mortality in adults if treatment was started within 48 h of the onset of influenza symptoms during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.4 However, some reports suggest that NAIs are unable to reduce serious complications, hospitalization or mortality.5–7 Serious complications, particularly pneumonia,8 can develop quickly and possibly lead to critical illness or death.9 Indeed, in the USA it is estimated that the annual rate of influenza-associated death ranges from 1.4 to 16.7 deaths per 100000 people.10 Thus, there is an unmet medical need for new antiviral drugs with an alternative mechanism of action that can effectively treat severe influenza infections.

The heterotrimeric RNA-dependent polymerase of influenza virus consists of subunits PA, PB1 and PB2. Cap-dependent endonuclease (CEN) is located in the N-terminal domain of the PA subunit and is essential for viral transcription and replication.11,12 In the process of ‘cap-snatching’, viral mRNA synthesis is initiated by PB2 binding to the cap structure of the host mRNA, followed by short-capped oligonucleotide cleavage by CEN. Intriguingly, CEN is well conserved among influenza virus strains and therefore considered to be an ideal anti-influenza virus drug target.13 Baloxavir marboxil (formerly S-033188), a first-in-class antiviral drug for the treatment of influenza, has been licensed in Japan and the USA. After oral administration, baloxavir marboxil is metabolized to the active form (baloxavir acid) that binds to CEN.14 In preclinical in vitro studies, baloxavir acid inhibited viral RNA transcription and replication.15–17 Furthermore, baloxavir marboxil significantly improved time to alleviation of influenza symptoms compared with placebo and reduced virus titre and duration of virus shedding more rapidly than an NAI in the first Phase 3 clinical trial (CAPSTONE-1).18

Antiviral combination therapy provides a theoretical benefit in reducing complications associated with influenza infection, particularly with the advent of new drugs with different mechanisms of action.19 In fact, combination regimens have been investigated for the treatment of critically ill patients.20 However, the therapeutic effect of delayed dosing of baloxavir marboxil, a CEN inhibitor, and its effect in combination with an NAI on signs of influenza infection in mice are still unknown.

In this study, we report the efficacy of 96 h-delayed oral dosing of baloxavir marboxil in a lethal mouse model of influenza virus infection. Here, we evaluated a wide range of outcome measures, including the role of cytokines/chemokines.21 Our results highlight the therapeutic efficacy of baloxavir marboxil and the potential benefits of combination therapy with an NAI, oseltamivir phosphate.

Methods

Cells, viruses, and compounds

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures) were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Richardson, TX, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma–Aldrich Co., Ltd, St Louis, MO, USA). Influenza A virus A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) strain was obtained from the ATCC. Baloxavir acid and baloxavir marboxil were synthesized at Shionogi & Co., Ltd (Osaka, Japan). Oseltamivir acid and laninamivir were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals Inc. (Toronto, ON, Canada). Peramivir trihydrate was purchased from AstaTech, Inc. (Philadelphia, PA, USA). Oseltamivir phosphate and zanamivir hydrate were purchased from Sequoia Research Products Ltd (Pangbourne, UK).

Combinational effects of baloxavir acid and NAIs in vitro

Confluent MDCK cells in 96-well assay plates were infected with influenza virus A/PR/8/34 strain at 200 TCID50/well. The infected cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1 h, followed by the addition of baloxavir acid and NAIs in serial dilutions (for baloxavir acid, 1.25–80 nmol/L; for oseltamivir acid, 156.25–40000 nmol/L; for zanamivir hydrate, 78.125–20000 nmol/L; for laninamivir and peramivir trihydrate, 7.8125–2000 nmol/L). After incubation for 2 days, cell viability was assessed using a WST-8 kit (Kishida Chemical Co., Ltd, Osaka, Japan), and absorbance was measured at 450 and 620 nm with a multiplate reader (EnVision, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Data were analysed according to the method of Chou and Talalay22 or using MacSynergy II software (University of Michigan). The EC50 for inhibition of influenza virus infection of each substance alone and at a fixed concentration of the other was determined using XLfit 5.3.1.3 for Microsoft Excel. To yield isobologram plots, (DA/A + B)/DA and (DB/A + B)/DB were plotted on the x- and y-axes, where DA is the EC50 of substance A alone, DB is the EC50 of substance B alone, DA/A + B is the concentration of substance A giving 50% inhibition in combination with substance B, and DB/A + B is the concentration of substance B giving 50% inhibition in combination with substance A. Combination index (CI) values, under the condition that both substances were added at the concentration ratio of each EC50 value, were calculated using the following formula: CI = (DA/A + B)/DA + (DB/A + B)/DB + (DA/A + B × DB/A + B)/(DA × DB). The combination effect was determined according to the following criteria: CI ≤ 0.8, synergy; 0.8 < CI < 1.2, additive; 1.2 ≤ CI, antagonism.

Evaluation of antiviral effects in vivo

Ethics

The study protocols for animal experiments were approved by the Shionogi & Co., Ltd. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Treatment of mice

Specific-pathogen-free, 6-week-old BALB/c mice (BALB/cAnNCrlCrlj, Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc.) were used for all experiments. On day 0, mice were intranasally inoculated with 100 μL of A/PR/8/34 strain at a lethal dose (8.00 × 102 TCID50/mouse) under anaesthesia. Uninfected control mice were intranasally administered with Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS, 100 μL). Starting on day 4 (96 h after virus infection), mice were administered treatment by oral gavage twice daily (at 12 h intervals) for 5 days; dose was determined by body weight (1 mL per 100 g body weight). Treatment groups (with variable numbers per outcome measure) were vehicle (0.5% w/v of methylcellulose aqueous solution); baloxavir marboxil at 0.5, 1.5, 15 or 50 mg/kg twice daily; oseltamivir phosphate at 10 or 50 mg/kg (as an active form) twice daily; and baloxavir marboxil (0.5 or 15 mg/kg) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 or 50 mg/kg) twice daily. Doses of baloxavir marboxil (see Discussion) and oseltamivir phosphate23 were selected with regard to human doses in the clinic.

Virus titre in lungs

On days 5, 6 and 7, mice (n = 5 per group) were euthanized and both lungs, without extra-pulmonary bronchi and trachea, were removed, weighed and homogenized with 2 mL of DPBS and antibiotics. Virus titres were measured by a standard TCID50 method using MDCK cells. Virus titres were expressed as log10 TCID50/mL; if no cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed at the lowest dilution (10-fold), titres of undetectable virus were defined as 1.5 log10 TCID50/mL.

Body weight and survival

Mice (n = 10 per group) were examined for survival and weighed daily from day 0 to day 28. If body weight was <70% of initial body weight prior to infection, mice were euthanized according to humane endpoints. For the analysis of body weight change, the current body weight as a proportion of initial body weight was evaluated from 1 day after starting treatment to 1 day after completing treatment (days 5–9). If a mouse died, the current body weight as a proportion of initial body weight at all timepoints after death was regarded as 70% (−30%).

Lung cytokines and chemokines

Frozen lung homogenates from the virus titre experiments were used (n = 5 per group). ELISAs for IL-6, IFN-γ, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Lung pathology

On days 7 and 28, mice were terminally anaesthetized and perfused with a transcardial injection of DPBS/10% neutral buffered formalin. Lungs were removed, dehydrated in ethyl alcohol and embedded in paraffin, and sections were cut and mounted on a glass slide (coated with indium tin oxide for scanning electron microscopy). For light microscopy, sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and observed using a light microscope (Eclipse E-800) equipped with a DXM-1200 digital camera system (Nikon, Japan). For scanning electron microscopy, slides were treated with 2% glutaraldehyde and then 1% OsO4, dehydrated with ethyl alcohol, which was then replaced with tertiary butyl alcohol, freeze-dried, covered with a thin layer of platinum/palladium and observed using a scanning electron microscope (S-3000N; Hitachi, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 5–15 kV.

Statistical analysis

For the mouse experiments, the uniformity of mean body weight and mean proportion of body weight to initial body weight among groups were confirmed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at group assignment. To assess the effect of combining baloxavir marboxil and oseltamivir phosphate, the combination therapy groups were compared with each monotherapy group. Comparisons of virus titres, cytokines and chemokines in the lungs, and lung weights were analysed by t-test or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Comparisons of proportion of body weight at each timepoint to initial body weight between two groups were analysed by one-way ANOVA, including the fixed effect of group and the contrast method. Comparisons of survival time were analysed by the log-rank test. The fixed-sequence procedure was used to adjust the multiplicity for the comparisons of proportion of body weight and survival time. Two-sided adjusted P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Effect of baloxavir acid in combination with NAIs in an in vitro system

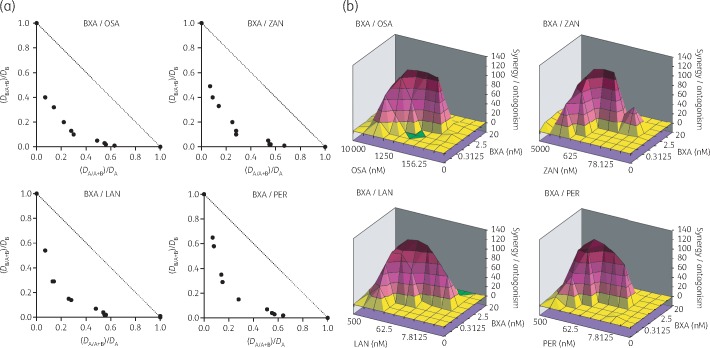

We first evaluated combination effects of baloxavir acid and NAIs by means of inhibition of virus infection-induced CPE in MDCK cells. By isobologram plot and MacSynergy analysis, combinations of baloxavir acid with oseltamivir acid, zanamivir hydrate, laninamivir and peramivir trihydrate resulted in CI values of 0.49, 0.52, 0.58 and 0.59, respectively, indicating that baloxavir acid exhibited synergistic effects with various types of NAI in vitro (Figure 1). Of note, there was no evidence of cytotoxicity for baloxavir acid or any combination.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effect of baloxavir acid (BXA) in combination with NAIs on CPE in cultured cells infected with influenza A virus. MDCK cells were infected with A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) in the presence of various concentrations of the indicated compounds and cell viability was assessed at 2 days post-infection. The combination effects are shown by isobologram plot (a) and MacSynergy analysis (b). For the isobologram plot, the EC50 of each substance alone and at a fixed concentration of the other were determined. (DA/A + B)/DA and (DB/A + B)/DB were plotted on the x- and y-axes, respectively; DA is the EC50 of substance A alone, DB is the EC50 of substance B alone, DA/A + B is the concentration of substance A giving 50% inhibition in combination with substance B, and DB/A + B is the concentration of substance B giving 50% inhibition in combination with substance A. LAN, laninamivir; OSA, oseltamivir acid; PER, peramivir trihydrate; ZAN, zanamivir hydrate.

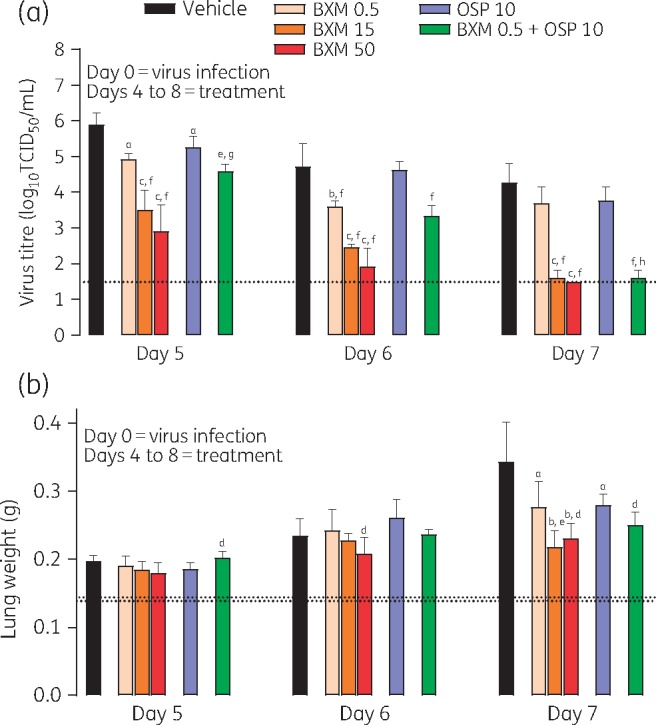

Baloxavir marboxil monotherapy or combination therapy with oseltamivir phosphate significantly reduced virus titre and prevented lung weight gain in mice lethally infected with influenza A/PR/8/34

To evaluate the effect of delayed oral dosing of baloxavir marboxil on virus replication, signs of virus infection (survival and body weight), virus-induced excessive lung inflammation and pathological changes in the lung, mice infected with a lethal dose of influenza A/PR/8/34 were treated with baloxavir marboxil, oseltamivir phosphate, baloxavir marboxil + oseltamivir phosphate or vehicle 96 h after infection.

In mice infected with virus, treatment with baloxavir marboxil delayed by 96 h significantly and dose-dependently reduced virus titre 24 h after administration (i.e. at day 5) compared with vehicle (Figure 2a). By day 7, virus titres in mice treated with baloxavir marboxil (15 and 50 mg/kg twice daily) were at or below the lower limit of detection (1.5 log10 TCID50/mL). In contrast, treatment with oseltamivir phosphate had little effect on virus titre compared with vehicle. As a result, virus titre in the baloxavir marboxil groups was significantly lower than in the oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) group on days 5–7. The combination treatment of baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) was more effective in reducing virus titre than either monotherapy alone.

Figure 2.

Virus titre (a) and lung weight (b) in mice infected with influenza virus and treated with antiviral. Data are presented as mean ± SD. The dotted line represents the lower limit of virus detection (a) or mean lung weight in uninfected, inoculated, control mice at day 7 (lower line) or normal uninoculated mice (upper line) (b). There were n = 5 mice per group. Differences between groups were analysed using Dunnett’s test for baloxavir marboxil (BXM) comparisons or the t-test for oseltamivir phosphate (OSP) and combination comparisons: aP < 0.05 versus vehicle, bP < 0.01 versus vehicle, cP < 0.0001 versus vehicle, dP < 0.05 versus OSP 10, eP < 0.01 versus OSP 10, fP < 0.0001 versus OSP 10, gP < 0.05 versus BXM 0.5 and hP < 0.0001 versus BXM 0.5. BXM, baloxavir marboxil; OSP, oseltamivir phosphate. Dosages shown for antiviral compounds are in units of mg/kg.

In mice infected with virus, lung weight increased over time (Figure 2b). By day 7, this increase in lung weight was inhibited by baloxavir marboxil (15 or 50 mg/kg twice daily) and baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) compared with vehicle and oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) monotherapy. Note that in a previous study24 lung weight increased following virus infection and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lungs.

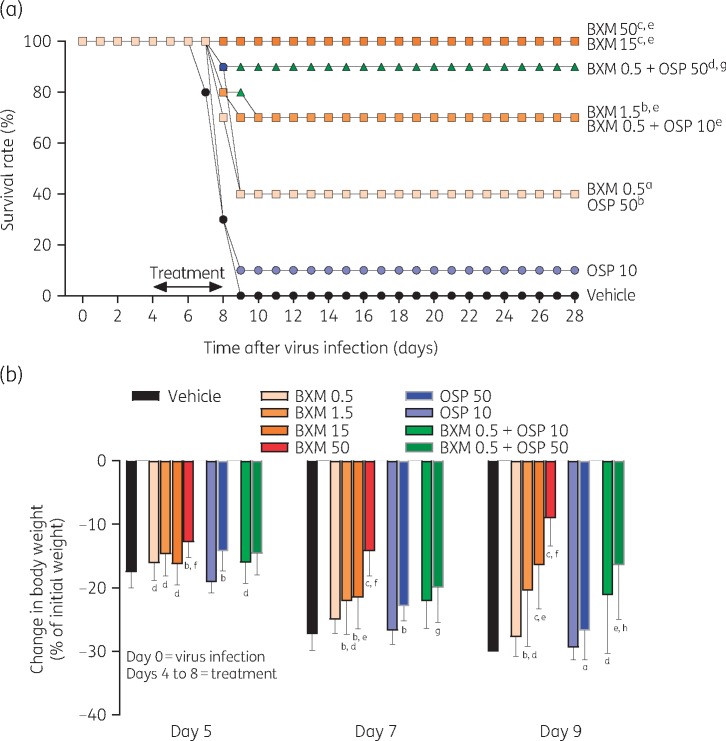

Baloxavir marboxil monotherapy or combination therapy with oseltamivir phosphate significantly prolonged survival and prevented body weight loss in mice lethally infected with influenza A/PR/8/34

In mice lethally infected with influenza A virus, mortality is induced via an excessive inflammatory response in the lungs.25,26 Treatment with baloxavir marboxil had a significant and dose-dependent protective effect on survival (Figure 3a). Treatment with baloxavir marboxil (15 and 50 mg/kg twice daily) completely eliminated mortality from virus infection. In contrast, survival rates with oseltamivir phosphate (10 and 50 mg/kg twice daily) were 10% and 40%, respectively. As a result, treatment with baloxavir marboxil (1.5, 15 and 50 mg/kg twice daily) significantly prolonged survival time compared with oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) treatment. The combination treatment of baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 or 50 mg/kg twice daily) provided more protection against mortality than either monotherapy alone.

Figure 3.

Survival rate (a) and change in body weight (b) in mice infected with influenza virus and treated with antiviral. Mice with a −30% change in body weight were euthanized according to humane endpoints and considered dead. For body weight, data are presented as mean ± SD. If a mouse died, the current body weight as a proportion of initial body weight at all timepoints after death was regarded as 70% (−30%). There were n = 10 mice per group. Differences between groups were analysed by log-rank test for survival and one-way ANOVA for body weight: aP < 0.05 versus vehicle, bP < 0.01 versus vehicle, cP < 0.0001 versus vehicle, dP < 0.05 versus OSP 10/50 (for body weight, day 5 and day 7 versus OSP 10), eP < 0.01 versus OSP 10/50 (for survival, BXM 1.5 versus OSP 10; for body weight, day 7 versus OSP 10), fP < 0.0001 versus OSP 10/50 (for body weight, day 5 versus OSP 10), gP < 0.05 versus BXM 0.5 and hP < 0.01 versus BXM 0.5. BXM, baloxavir marboxil; OSP, oseltamivir phosphate. Dosages shown for antiviral compounds are in units of mg/kg.

Loss in body weight due to virus infection was inhibited within 1 day after initial treatment (day 5) with all doses of baloxavir marboxil (Figure 3b). At the higher doses of baloxavir marboxil, loss of body weight was minimal and correlated with the elimination of mortality in these groups. Baloxavir marboxil (1.5, 15 or 50 mg/kg twice daily) was more effective than oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) in preventing loss of body weight throughout the study. Baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 or 50 mg/kg twice daily) seemed to provide more protection against loss of body weight than either monotherapy alone [baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) or oseltamivir phosphate (10 or 50 mg/kg twice daily)], particularly at day 9. Given the virus titre results, we suggest that the effect of baloxavir marboxil on body weight was via its rapid and potent inhibition of virus replication.

Baloxavir marboxil monotherapy or combination therapy with oseltamivir phosphate inhibited virus-induced lung inflammation in mice lethally infected with influenza A/PR/8/34

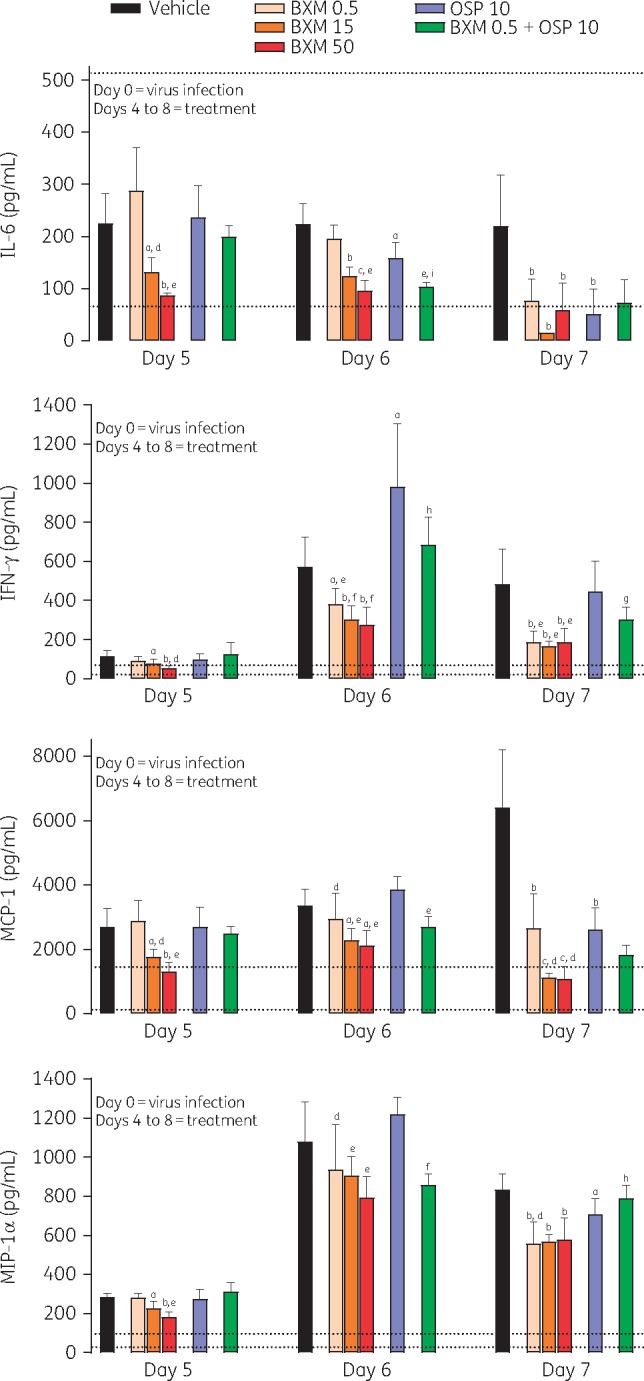

The levels of IL-6, IFN-γ, MCP-1 and MIP-1α in the lungs increased following virus infection, and this increase was maintained until at least day 7 (Figure 4). This increase in cytokines/chemokines was significantly inhibited compared with vehicle within 24 h of treatment (at day 5) with baloxavir marboxil (15 and 50 mg/kg twice daily); by day 6 (day 7 for IL-6), baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) was also able to reduce these levels. The effect of oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) monotherapy on cytokine/chemokine levels was variable and limited. Baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) partially suppressed the increase in IL-6 and MCP-1 compared with each monotherapy. Levels of IL-6 and MCP-1 were positively correlated with virus titre at day 5, and levels of MCP-1 and MIP-1α were positively correlated with lung weight at day 6. In addition, cytokine and chemokine levels were positively correlated with each other at day 5 (Figure S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Figure 4.

Cytokine and chemokine levels in the lungs of mice infected with influenza virus and treated with antiviral. Data are presented as mean ± SD. The lower dotted line represents the mean level in uninfected control mice, and the upper dotted line represents the mean level in infected mice at day 4 (immediately before starting treatment). There were n = 5 mice per group. Differences between groups were analysed using Dunnett’s test for baloxavir marboxil (BXM) comparisons or the t-test for oseltamivir phosphate (OSP) and combination comparisons: aP < 0.05 versus vehicle, bP < 0.01 versus vehicle, cP < 0.0001 versus vehicle, dP < 0.05 versus OSP 10, eP < 0.01 versus OSP 10, fP < 0.0001 versus OSP 10, gP < 0.05 versus BXM 0.5, hP < 0.01 versus BXM 0.5 and iP < 0.0001 versus BXM 0.5. Dosages shown for antiviral compounds are in units of mg/kg.

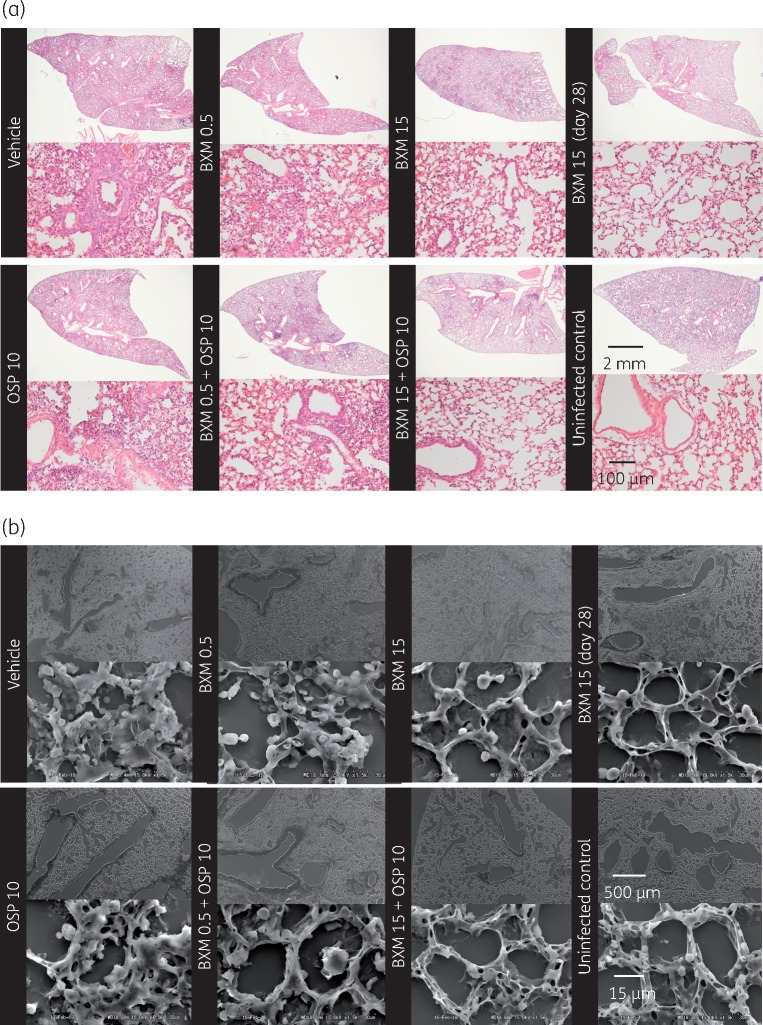

Lung sections were examined by light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy for changes in lung morphology (Figure 5). Infection with virus led to infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, into the lung and diffusely caused pathological changes in the lung structure, including alveolar damage, oedema, capillary bleeding, hyperplasia, epithelial cell swelling/peeling and vascular hyperpermeability via hyaline membrane formation. On day 7, treatment with baloxavir marboxil (15 mg/kg twice daily) prevented these severe morphopathological changes and limited the inflammation to a small area of the lung. In contrast, oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) or a suboptimal dose of baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) provided little or no protective effect, and the lungs appeared similar to those of the vehicle group. The combination of baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily) prevented lung damage compared with each monotherapy. In this study, no additional efficacy was detected when the mice were treated with baloxavir marboxil (15 mg/kg twice daily) + oseltamivir phosphate (10 mg/kg twice daily), but no harmful or antagonistic effect was observed by concomitant administration with baloxavir marboxil and oseltamivir phosphate.

Figure 5.

Lung pathology at day 7 in mice infected with influenza virus on day 0 and treated with antiviral on days 4–8. Sections of lung were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and observed with light microscopy (a) and scanning electron microscopy (b). Representative sections are presented. BXM, baloxavir marboxil; OSP, oseltamivir phosphate.

Discussion

In our lethal mouse model of influenza A virus infection, delayed oral dosing with baloxavir marboxil effectively prevented signs of infection. The results suggest that baloxavir marboxil acts by reducing virus titre, leading to a suppressed increase in the early-response proinflammatory cytokines in a lethal mouse model. This subsequently leads to lower chemokine levels and reduced excess infiltration of inflammatory cells such as macrophages and neutrophils into the lung, thus protecting the lungs from prolonged inflammation and pathological changes. In contrast, the NAI oseltamivir phosphate had little effect, except in combination with baloxavir marboxil. Indeed, the combination of baloxavir marboxil and a range of NAIs was synergistic in an in vitro assay. These findings support baloxavir marboxil alone and in combination therapy with oseltamivir phosphate as treatment options for patients with serious complications from influenza virus infection.

Combination therapy with antivirals has been investigated as an ideal treatment regimen against influenza infection in mice. For example, the combinations of oseltamivir phosphate + peramivir trihydrate27 and oseltamivir phosphate + favipiravir28,29 have both been shown to have a positive synergistic effect on survival in a lethal mouse model of influenza virus infection. In addition, more recently the combinational benefit of oseltamivir phosphate + MEDI8852, an antibody against haemagglutinin, has been reported.30 Similarly, in our study baloxavir acid was synergistic with a range of NAIs in an in vitro CPE assay. We also found that the combination of oseltamivir phosphate with a suboptimal dose of baloxavir marboxil was more effective than oseltamivir phosphate monotherapy in reducing virus titre and improving survival, body weight and lung pathology in mice. However, although combination treatments have shown promise in laboratory studies, they have not, to date, been successful in the clinic. For example, both oseltamivir + zanamivir in a clinical trial31 and oseltamivir + peramivir in a retrospective clinical study32 were less effective than oseltamivir monotherapy; however, these drugs have a similar mechanism of action. In light of our findings, and given that baloxavir marboxil has an alternative mechanism of action, there are more potential benefits with baloxavir marboxil, such as reduction of both emergence of drug-resistant viruses and contact transmission; thus, future clinical investigations of baloxavir marboxil in combination with an NAI are worthy of consideration in a patient population with, or at risk of, severe infection and complications.

The key point of our mouse study was the dosing regimen, including oral administration, delayed dosing and a clinically relevant dose, which reflected clinical practice. Using pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis, the target plasma concentration of baloxavir acid was set at 6.85 ng/mL, which was the plasma concentration at the end of the dosing interval after the initial dose (CT) obtained by 15 mg/kg twice-daily oral dosing with baloxavir marboxil in our mouse efficacy model, to exert greater virus reduction compared with oseltamivir phosphate.33 On the other hand, on the basis of the results of the Phase 1 and 2 studies, 40 mg (or 80 mg if body weight >80 kg) was selected as the clinical dose for baloxavir marboxil (single dose), and its efficacy was confirmed in a Phase 3 study at this dose level.18,34 Although it is difficult to set a clinically equivalent dose regimen in mice owing to the crucial difference in half-life of baloxavir acid in plasma between humans (85.9 h at 40 mg) and mice (2.26 h at 15 mg/kg), we confirmed that the plasma concentration of baloxavir acid could be maintained above the target concentration of 6.85 ng/mL for at least 5 days following oral administration of baloxavir marboxil at 40 mg in humans as well as 15 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days in mice. Taking the results together, in this study the efficacy of baloxavir marboxil was evaluated in mice treated at 15 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days to predict clinical effectiveness. In contrast, for our study the dose of oseltamivir phosphate was calculated based on human pharmacokinetic data: in mice, 5 mg/kg twice daily is equivalent to the human clinical dose,35 and for the treatment of critically ill patients double the high dose is recommended.23,36 Therefore, in the current study mice were treated with 10 mg/kg twice daily (double the high dose) or 50 mg/kg twice daily (10 times the high dose) of oseltamivir phosphate as the reference drug treatment.

As expected, the levels of both IL-6 and MCP-1, which play key roles in the early inflammatory response to virus infection and the subsequent infiltration of macrophages/neutrophils, increased with virus infection in our mouse model, and baloxavir marboxil or baloxavir marboxil + oseltamivir phosphate suppressed the increase in these inflammatory markers. The levels of IL-6 and MCP-1 in the lungs were positively correlated with virus titre, suggesting that baloxavir marboxil ameliorated lung inflammation via prevention of virus replication. Baloxavir marboxil treatment also reduced levels of MIP-1α, a chemokine for T cell infiltration; this was consistent with reduced levels of IFN-γ, which is secreted by activated T cells and macrophages. We propose that these protective effects of baloxavir marboxil against virus-induced inflammation in the lungs lead to conservation of lung structure.

Although the current study was limited by the inclusion of only one strain of virus, our previous studies have examined the therapeutic efficacy of baloxavir marboxil against a range of virus strains and types, including oseltamivir-resistant H1N1, H3N2, B and avian H7N9 and H5N1.16,37–39 In these studies, baloxavir marboxil at 5 or 15 mg/kg (twice daily) significantly lowered virus titres compared with clinically equivalent doses of oseltamivir phosphate; at 15 mg/kg the reduction in virus titre was at least a log greater than that obtained with oseltamivir phosphate. In addition, baloxavir marboxil protected mice infected with type B and avian H7N9 and H5N1 virus against lethality.37–39 Therefore, we expect that the delayed treatment with baloxavir marboxil may be effective against lethal infection with a wide range of virus strains. In the current study, the combination effect was determined for oseltamivir phosphate and a suboptimal dose of baloxavir marboxil in our lethal mouse model. As indicated in Figure S2, we confirmed that the combination of a regular dose of baloxavir marboxil (15 mg/kg twice daily) with oseltamivir phosphate provides some benefits for body weight compared with each monotherapy. However, baloxavir marboxil (15 mg/kg twice daily) monotherapy completely eliminated mortality (100% survival), significantly ameliorated pathological changes in lung structure and potently ameliorated body weight loss. Therefore, in this study, the combination effect was determined by combining oseltamivir phosphate with a suboptimal dose of baloxavir marboxil (0.5 mg/kg). To confirm the precise combination potential and to prove the mechanistic basis of the combination effects with baloxavir marboxil and NAIs in vivo, further research is needed with regard to more severe situations, such as immunocompromised or other severe infection models, in which the efficacy of monotherapy with baloxavir marboxil may be insufficient.

Conclusions

Delayed oral dosing with baloxavir marboxil was able to rapidly and potently reduce virus titre and thus prevent the virus-induced severe inflammatory response and subsequent mortality in a mouse model of influenza A virus infection. Of note, baloxavir marboxil in combination with oseltamivir phosphate was more effective than each monotherapy, supporting baloxavir marboxil and oseltamivir phosphate combination therapy as a treatment option for patients with serious complications from influenza virus infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiroki Sakaguchi, Masashi Furukawa and members of the Biostatistics Center (Shionogi & Co., Ltd) for statistical analysis; Takeki Uehara, Masahiro Kinoshita and all members of the discovery research programme and clinical development team (Shionogi & Co., Ltd) for providing valuable suggestions and assistance in manuscript preparation. All work reported here was financially supported by Shionogi & Co., Ltd. Medical writing assistance was provided by Janelle Keys, PhD, CMPP and Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

The contents of this manuscript were presented at two conferences: IDWeek 2017, San Diego, CA, USA, 4–8 October 2017 (Posters 1214 and 1514) and 28th ECCMID, Madrid, Spain, 21–24 April 2018 (Abstract 3605).

Funding

This study was sponsored by Shionogi and Co., Ltd (Osaka, Japan), manufacturer/licensee of baloxavir marboxil. Medical writing assistance was also funded by Shionogi.

Transparency declarations

All authors are employees of Shionogi and Co., Ltd or Shionogi TechnoAdvance Research, Co., Ltd, an affiliation of Shionogi. K. F., T. N., M. K., Y. A., K. B., M. I., T. S. and A. N. also own stocks in the company.

References

- 1. Su B, Wurtzer S, Rameix-Welti MA. et al. Enhancement of the influenza A hemagglutinin (HA)-mediated cell-cell fusion and virus entry by the viral neuraminidase (NA). PLoS One 2009; 4: e8495.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moscona A. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sheu TG, Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M. et al. Surveillance for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among human influenza A and B viruses circulating worldwide from 2004 to 2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 3284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR. et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heneghan CJ, Onakpoya I, Thompson M. et al. Zanamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ 2014; 348: g2547.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P. et al. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ 2014; 348: g2545.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones M, Jefferson T, Doshi P. et al. Commentary on Cochrane review of neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21: 217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kash JC, Taubenberger JK.. The role of viral, host, and secondary bacterial factors in influenza pathogenesis. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 1528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taubenberger JK, Morens DM.. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol 2008; 3: 499–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza—United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59: 1057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DuBois RM, Slavish PJ, Baughman BM. et al. Structural and biochemical basis for development of influenza virus inhibitors targeting the PA endonuclease. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8: e1002830.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plotch SJ, Bouloy M, Ulmanen I. et al. A unique cap(m7GpppXm)-dependent influenza virion endonuclease cleaves capped RNAs to generate the primers that initiate viral RNA transcription. Cell 1981; 23: 847–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yuan P, Bartlam M, Lou Z. et al. Crystal structure of an avian influenza polymerase PA(N) reveals an endonuclease active site. Nature 2009; 458: 909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omoto S, Speranzini V, Hashimoto T. et al. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noshi T, Yamamoto A, Kawai M. et al. S-033447/S-033188, a novel small molecule inhibitor of cap-dependent endonuclease of influenza A and B virus: in vitro antiviral activity against clinical strains. In: Abstracts of IDWeek, New Orleans, LA, USA,2016. Poster 645.

- 16. Noshi T, Tachibana H, Yamamoto A. et al. S-0033447/S-033188, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Cap-dependent endonuclease of influenza A and B virus: in vitro antiviral activity against laboratory strains of influenza A and B virus in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney Cells. In: Abstracts of OPTIONS IX, Chicago, IL, USA,2016. Poster 418.

- 17. Shishido T, Omoto S, Ishida K. et al. S-033447/S-033188, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Cap-dependent endonuclease (CEN) of influenza A and B virus: in vitro inhibitory effect of S-033447 on CEN activities of influenza A and B virus. In: Abstracts of OPTIONS IX, Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. Poster 185.

- 18. Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N. et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 913–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ison MG. Finding the right combination antiviral therapy for influenza. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 1221–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koszalka P, Tilmanis D, Hurt AC.. Influenza antivirals currently in late-phase clinical trial. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2017; 11: 240–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newton AH, Cardani A, Braciale TJ.. The host immune response in respiratory virus infection: balancing virus clearance and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol 2016; 38: 471–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chou TC, Talalay P.. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 1984; 22: 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flannery AH, Thompson Bastin ML.. Oseltamivir dosing in critically ill patients with severe influenza. Ann Pharmacother 2014; 48: 1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sidwell RW, Barnard DL, Day CW. et al. Efficacy of orally administered T-705 on lethal avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51: 845–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garigliany MM, Habyarimana A, Lambrecht B. et al. Influenza A strain-dependent pathogenesis in fatal H1N1 and H5N1 subtype infections of mice. Emerg Infect Dis 2010; 16: 595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Julkunen I, Melén K, Nyqvist M. et al. Inflammatory responses in influenza A virus infection. Vaccine 2000; 19 Suppl 1: S32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smee DF, Hurst BL, Wong MH. et al. Combinations of oseltamivir and peramivir for the treatment of influenza A (H1N1) virus infections in cell culture and in mice. Antiviral Res 2010; 88: 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smee DF, Tarbet EB, Furuta Y. et al. Synergistic combinations of favipiravir and oseltamivir against wild-type pandemic and oseltamivir-resistant influenza A virus infections in mice. Future Virol 2013; 8: 1085–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marathe BM, Wong SS, Vogel P. et al. Combinations of oseltamivir and T-705 extend the treatment window for highly pathogenic influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in mice. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 26742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paules CI, Lakdawala S, McAuliffe JM. et al. The hemagglutinin A stem antibody MEDI8852 prevents and controls disease and limits transmission of pandemic influenza viruses. J Infect Dis 2017; 216: 356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duval X, van der Werf S, Blanchon T. et al. Efficacy of oseltamivir-zanamivir combination compared to each monotherapy for seasonal influenza: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med 2010; 7: e1000362.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Gao H, Liang W. et al. Efficacy of oseltamivir-peramivir combination therapy compared to oseltamivir monotherapy for influenza A (H7N9) infection: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Noshi T, Sato K, Ishibashi T. et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of S-033188/S-033447, a novel inhibitor of influenza virus Cap-dependent endonuclease, in mice infected with influenza A virus. In: Abstracts of the 27th ECCMID, Vienna, Austria,2017. Poster 1973.

- 34. Koshimichi H, Ishibashi T, Kawaguchi N. et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the novel anti-influenza agent baloxavir marboxil in healthy adults: phase 1 study findings. Clin Drug Investig 2018; doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sharma G, Champalal Sharma D, Hwei Fen L. et al. Reduction of influenza virus-induced lung inflammation and mortality in animals treated with a phosophodisestrase-4 inhibitor and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Emerg Microbes Infect 2013; 2: e54.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ward P, Small I, Smith J. et al. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and its potential for use in the event of an influenza pandemic. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 55 Suppl 1: i5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fukao K, Ando Y, Noshi T. et al. One day oral dosing of S-033188, a novel inhibitor of influenza virus cap-dependent endonuclease, exhibited significant reduction of viral titer and prolonged survival in mice infected with influenza B virus. In: Abstracts of the 27th ECCMID, Vienna, Austria, 2017. Poster 2175.

- 38. Taniguchi K, Ando Y, Noshi T. et al. Inhibitory effect of S-033188, a novel inhibitor of influenza virus Cap-dependent endonuclease, against avian influenza A/H7N9 virus in vitro and in vivo. In: Abstracts of ESWI, Riga, Latvia,2017. Abstract SPA4P09.

- 39. Taniguchi K, Ando Y, Noshi T. et al. Inhibitory effect of S-033188/S-033447, a novel inhibitor of influenza virus cap-dependent endonuclease, against a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/H5N1. In: Abstracts of the 27th ECCMID, Vienna, Austria,2017. Poster 1974.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.