Abstract

Introduction

Although advocacy and social determinants of health (SDH) are fundamental components of pediatrics and other areas of health care, medical education often lacks formal training about these topics and the role of health care professionals as advocates. SDH are common targets of advocacy initiatives; however, little is known about optimal ways to incorporate this content into medical education curricula.

Methods

We developed a lecture and assessment for third-year medical students that included interactive discussion of advocacy, SDH issues specific to children, and opportunities for learners to engage in advocacy. Learners attended the lecture during the pediatric clerkship. Over the course of a year, questionnaires assessing knowledge of advocacy, SDH, and incorporation of advocacy into practice were administered to 75 students before the lecture and as the clerkship ended. We used chi-square and Fisher's exact tests to compare knowledge before and after the lecture.

Results

Students showed significant improvement on most individual questions and overall passing rates. Learners provided positive feedback on the quality of the lecture material and demonstrated interest in engaging in current advocacy projects to address SDH.

Discussion

As recognition of the importance of advocacy and SDH increases, the development of educational tools for teaching this information is critical. Our lecture produced significant improvement in knowledge of these topics and was well received by students. Early introduction to advocacy and SDH during relevant clinical rotations emphasizes the importance of these topics and may establish a foundation of advocacy as fundamental to health care.

Keywords: Social Determinants of Health, Advocacy, Diversity

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, learners will be able to:

-

1.

Define advocacy and social determinants of health (SDH).

-

2.

Describe advocacy and attention to SDH as fundamental to the delivery of pediatric care and to the field of pediatrics.

-

3.

Explore examples of SDH and how they can impact children's health.

-

4.

Reflect on prior training experiences with advocacy and consider engaging in ongoing advocacy projects.

Introduction

Pediatricians advocate for children who cannot advocate on their own behalf. Advocacy is a broad term that involves active engagement to improve the health and well-being of children, families, and communities, whether on an individual level, in communities, or through legislative work on the state or national scale. Advocacy efforts often seek to address social determinants of health (SDH), defined as economic, environmental, and psychosocial conditions that shape health outcomes of children, families, and communities.1 Pediatricians routinely screen children and families for SDH and support population-level efforts to protect the health and well-being of future generations.1–3 Although they are distinct areas, SDH and advocacy are inherently intertwined, as SDH are often natural targets of advocacy initiatives.

There has been increasing national attention to education about child advocacy from which several large educational initiatives have stemmed. For example, the LEADS (Leadership Education Advocacy Development Scholarship) Program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine is one attempt to train medical students to become effective advocates at a community level. The LEADS curriculum includes several weeks of didactic sessions, summerlong internships, and regular meetings.4 Barriers to implementing such programs are that they are time intensive, often attract only the students already interested in this type of learning, and involve a significant amount of financial buy-in for summer stipends, faculty time, and administrative support. The call to action has shifted to also include understanding of SDH and opportunities to address SDH in graduate medical education. “As a consequence of the importance of SDH and physicians' role in addressing them, medical societies increasingly highlight their work in advocacy and the promotion of social justice.”5 Although medical students work closely with some of the most vulnerable populations and SDH remain a major driver of health outcomes, SDH education is still often considered optional.5

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires pediatric trainees to be exposed to the topics of SDH and advocacy during their residency training. More specifically, the ACGME states that

pediatricians should advocate for the well-being of patients, families, and communities; must develop advocacy skills to address relevant individual, community, and population health issues; and understand the legislative process (local, state, and federal) to address community and child health issues.6

While a curriculum has not yet been standardized, a set of objectives developed by a group of pediatric advocacy experts is available.7,8 Education surrounding these topics thus has been implemented for pediatric residents.9,10

Despite the integration of this type of education at the residency level, only a small subset of medical schools includes lectures on advocacy and SDH as part of medical education.11–17 Undergraduate medical education, however, provides a unique opportunity to teach all students about these topics prior to specialization.18 To address this knowledge gap at our institution, a group of educators, with close senior faculty mentorship, developed and gave a lecture to third-year medical students during their pediatric clerkship. The lecture included education on defining advocacy and SDH, recognition of advocacy and SDH as fundamental components of health care, and examples of how advocacy can be incorporated into practice. After piloting the lecture for a year, we developed a pediatric advocacy assessment questionnaire to assess whether knowledge of these topics was improved by our lecture.

Although advocacy training is often viewed as experiential learning, we believe that teaching about the history and principles of advocacy can begin in a traditional classroom setting. The learning activity described here aims to improve medical students' knowledge about advocacy and SDH and to emphasize the important relationship between the two concepts. We discuss real-world instances of advocacy that go beyond its traditional definition as legislative and policy work alone, we highlight disparities that persist, and we include examples of ongoing projects and culturally relevant community-based initiatives as essential components of advocacy.19–22 Arming learners with knowledge of inequities that need to be rectified and ways in which to address such disparities is essential to the success and the sustainability of these projects and initiatives. This learning module therefore can serve as an adjunct to the variety of existing resources, such as instructional videos and service learning experiences, or as an introduction or alternative to monthlong courses.13,15,23,24 While some of these other resources address pediatric-specific issues, we feel that child health deserves its own separate curriculum. Our learning activity aims to demonstrate the importance of addressing SDHs early within a child's life. Our activity also highlights a way of implementing this type of lecture within the pediatric clerkship, which is unique to the MedEdPORTAL literature within the realm of advocacy and SDH.

Methods

Lecture Development and Procedure

After reviewing medical education literature focused on advocacy and SDH, we developed a lecture for third-year medical students (Appendix A). The lecture included four main sections. Section 1 explored the historical foundations and definitions of advocacy and SDH. Section 2 discussed the link between SDH and advocacy, including an emphasis on why these two concepts were fundamental to the delivery of high-quality pediatric care. Strategies for tackling difficult topics and resources for further debriefing were provided, including contact information for supervising faculty members, ethics committees, anonymous reporting systems, and the service excellence department. Section 3 took a further plunge into issues related to advocacy and SDH in pediatrics, specifically, the topics of adverse childhood experiences, health insurance, food insecurity, safety, and childhood vaccines.25 Section 3 was not intended as a representation of all areas of SDH but rather as an introduction to topics that pediatricians encounter daily. Safety and childhood vaccines are not SDH, but they are heavily impacted by multiple SDH, including income, urban/rural, culture, and religion. Section 4 encouraged reflection on prior training experiences and also included examples of ongoing faculty and resident advocacy projects. These examples should be tailored by future presenters to include projects at their own institution or in their community. We encourage further iterations of this presentation to include national and worldwide data to help develop a broader understanding of child health. For example, we suggest an extension to include discussion of the six major topics found on the Child Health Initiative agenda.26 These include the following:

-

•

Every child has the right to use safe roads.

-

•

Every child has the right to breathe clean air.

-

•

Every child has the right to an education.

-

•

Every child has the right to explore in safety.

-

•

Every child has the right to protection from violence.

-

•

Every child has the right to be heard.

Educator Training

We trained resident educators to give the lecture after completing the Pediatric Residency Program advocacy curriculum, including ongoing mentorship by faculty with expertise in advocacy, immigrant child health, child nutrition, and health disparities. The advocacy curriculum included multiple components. First, educators took part in a community plunge—a tour of our community and a community-led panel discussion of community factors influencing the health, education, and care of children. This experience typically lasted 4 hours. Next, educators participated in site visits to patient homes, schools, childcare centers, and other community-based organizations to enhance their understanding of community health needs and to apply this understanding to their own clinical practice. Each site visit lasted about half a day. Educators also attended several hour-long academic conferences by faculty and guest lecturers and completed a selection of modules on core topics related to SDH and advocacy, such as community health; poverty and SDH; legislation and policy; school health, school readiness, and child care; toxic stress, child abuse, and neglect; special populations; global health; and environmental health. Finally, educators completed an advocacy project of their own with appropriate faculty mentorship. This experience allowed educators to better teach these concepts to learners.

In addition to the advocacy curriculum, educators also completed a monthlong medical educational experience that focused on building a teaching portfolio and developing skills to teach different levels of learners. Activities included facilitation of medical student morning reports, clinical skills seminars, patient simulation sessions, bedside clinical teaching, rounds observations, and presentation of didactic lectures. This experience incorporated ongoing self-assessments and faculty-observed assessments, as well as a review of the literature on current teaching techniques and methods.

These two courses were followed by a 1-hour period of direct faculty observation of the educators speaking on topics of advocacy and SDH to students. We feel that any instructor already engaged in education and advocacy at a medical school or residency level would be sufficiently prepared to give this lecture with the assistance of the speaker notes found in the PowerPoint. With regard to the advocacy training, a basic understanding of the current initiatives in the community coupled with training during a pediatric residency should provide an appropriate foundation for teaching on these topics. Alternatively, partnership with local community experts and organizations could support delivery of this content, particularly regarding experience with how SDH affect families and communities.

Lecture Implementation

We scheduled learners for the lecture during their pediatric clerkship as part of the didactic curriculum. The learners included third-year medical students and second-year physician assistant students rotating through the pediatric clerkship; however, physician assistant students did not participate in the pre- and postlecture assessments. Students had various levels of prior exposure to SDH and advocacy. Lectures occurred once during the 6-week pediatric clerkship rotation from October 2016 to October 2017. Lecture groups included eight to 14 students for whom attendance was mandatory when working daytime hours. The lecture lasted 45–60 minutes and was given by at least one of three trained resident educators. We found that each student group came to the lecture with various interests or levels of engagement with certain topics. The lecture could be altered to focus more or less on particular sections to address time limitations. Alternatively, the lecture could be extended by an additional 30 minutes or more to allow a more in-depth discussion.

Lectures were held in a small classroom. PowerPoint accessibility with projector capability was necessary. We found that horseshoe seating around a conference table was helpful to facilitate discussion. A whiteboard could also be beneficial for brainstorming.

Lecture Assessment

We developed a pediatric advocacy assessment questionnaire (PAAQ) to assess the lecture's ability to improve students' knowledge about advocacy and SDH (Appendix B). The PAAQ was developed by residents and advocacy faculty at our institution and reviewed by members of the teaching faculty with medical education training. The PAAQ included knowledge-based questions and a self-assessment of advocacy skills on a 5-point Likert-type scale indicating best and worst performances. The PAAQ was not part of our learning module, nor is it intended to be implemented at other institutions, but it may be so if desired. Alternatively, institutions may choose to select questions from the assessment to include in their end-of-rotation evaluation.

The lecture started with the administration of the PAAQ as a pretest. Every student who attended the lecture was required to take the pretest. The PAAQ was provided twice—once prior to the advocacy lecture and once at the end of the pediatric rotation. Several students who had attended the lecture were not available at the end of the rotation to take the posttest given scheduling conflicts.

Immediately after the lecture, students were asked to complete a standardized anonymous written evaluation that included a narrative component and a scaled score from 1–10 on the following areas: knowledge in their field, effectiveness in teaching, capacity to inspire students, influence as a role model, communication skills, preparation, organization, and ability to relate to students (Appendix C). This evaluation was standard for all medical student lectures in our department. It could easily be altered to a scaled score of 1–5 to reflect a scoring system similar to the Likert scale if desired.

A passing PAAQ score was defined as a score of at least 70%, which was consistent with other examinations administered during the pediatric clerkship (Appendix D). We used chi-square and Fisher's exact tests to compare overall knowledge (mean number of questions answered correctly), the percentage of passing scores, and individual item responses before and after lecture participation. All p values were calculated based on two-tailed tests and compared with a significance level of .05. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata 14.2. This activity was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Results

Between October 27, 2016, and October 25, 2017, 130 medical students rotated through the pediatrics clerkship, 75 of whom attended the lecture during one of eight separate rotations. Although attendance at the lecture was required, approximately half of each group of students were on their outpatient elective and could not attend. Students completed 75 pretests and 53 posttests. Overall, students significantly improved their knowledge of advocacy issues, with a mean number of 5.71 ± 1.38 correct pretest questions and 7.38 ± 1.29 correct posttest questions (p < .001). Significantly more students received a passing test score after the lecture (65.5% vs. 34.6%, p < .001).

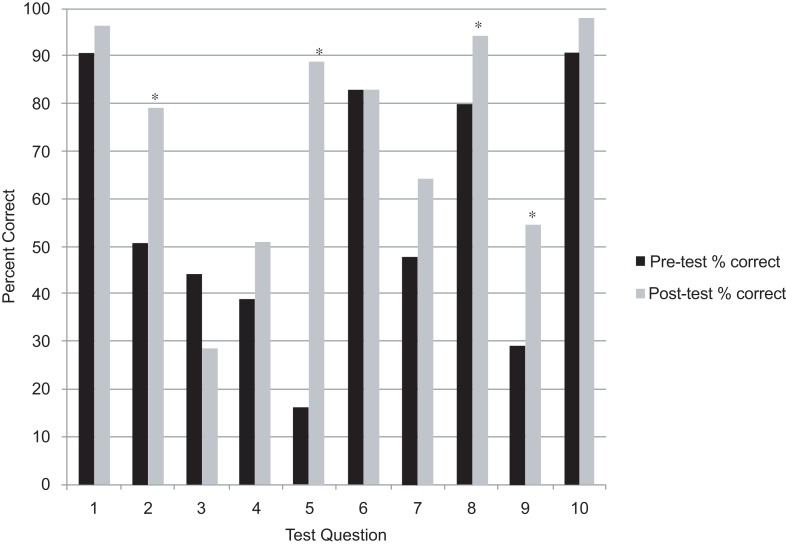

Analysis of individual test questions revealed an increase in the number of correct answers for all questions except for question 3 (see the Figure). After the lecture, students were significantly more likely to correctly answer question 2 (50.7% vs. 79.2%, p = .001), question 5 (16.0% vs. 88.7%, p < .001), question 8 (80.0% vs. 94.3%, p = .02), and question 9 (29.3% vs. 54.7%, p = .004). The question least commonly answered correctly prior to the lecture (16.0%) was question 5, which assessed childhood hunger in our city; 88.7% answered this question correctly after the lecture.

Figure. Pre- versus posttest percentage of correct answers. Asterisks denote statistically significant changes (p < .05).

Learner feedback forms demonstrated that evaluation scores for the resident educators were comparable to scores received by senior faculty–led clerkship lecturers. Learners also gave positive feedback about the lecture, and students expressed interest in becoming involved in advocacy projects. In particular, students were further empowered, as demonstrated by these quotes:

-

•

“After our lecture today, I am incredibly interested in joining and/or helping with a project in any way that would be useful.”

-

•

“Thanks for having this talk. It's probably the first nonshelf geared lecture we've had, [and] it's so important to learn about community resources and realize our role as patient advocates.”

-

•

“Really enjoyed this lecture, not something we are typically exposed to in school.”

-

•

“I am glad that this presentation was given to us; it further informed me of various ways to get involved with helping people on a bigger scale outside of one on one patient time. I [feel] more inspired to participate in child advocacy and I know who to reach out to [if] I decide to participate in a project!”

Discussion

Our lecture is one effort to contribute to the growing body of learning resources on SDH and advocacy. We offered a didactic, instructional foundation for key concepts about SDH and advocacy, the natural intersection between the two, and their inherent importance within pediatrics and health care. Our lecture also provided an example of how these topics could be better incorporated into the core medical student curriculum during the clerkship rotations in both a time-efficient and cost-effective manner. We demonstrated that students showed significant improvement in knowledge about SDH and advocacy after our brief intervention without having to attend time-intensive courses throughout the year. Additionally, although we were able to capture only half of the rotating third-year students (due to scheduling conflicts), incorporating this lecture as a mandatory didactic experience helped to develop a workforce committed to investing in a culture of health for children and families. Perhaps more importantly, students gave positive feedback about the learning experience, commenting that they enjoyed learning about these topics and felt inspired and empowered to seek out projects to join. The students themselves acknowledged that they had previously received limited education on these important topics and would like to learn more.

In an effort to meet our objectives and continue to improve our content, we have continued to adapt our material based on the results of our survey, informal feedback, and conversations with medical school leadership that have emerged based on student interest. First, with respect to the presentation itself, to better teach the desired content, we altered the way we discussed question 3 during our lecture after learning that students did worse on this question than on all others. The lecture slides now reflect this change and the racial disparities that exist around adverse childhood experiences and minority groups. Second, we have considered opportunities to expand student engagement in advocacy and have adapted our presentation to facilitate student involvement in projects with pediatric residents and in broader efforts. A natural limitation of this educational intervention is the possibility of knowledge degradation over time. This could and should be addressed by frequent refresher courses, potentially in other fields such as family medicine or obstetrics or as part of a longitudinal curriculum in professionalism in other studies. Future considerations also include earlier introduction of this curriculum to first- and second-year medical students. There has been an increasing effort to discuss ideas such as advocacy as part of the hidden curriculum offered in the preclinical years. As a result, we have tried to incorporate a breadth of topics relevant to advocacy and SDH to meet the diverse interests of learners who may not have been exposed to them in the preclinical setting. We have found that introducing these concepts later, during the clinical rotations, somewhat limits students' efforts and involvement in advocacy projects. This effect is seen particularly in third-year students rotating through the pediatric clerkship at the end of their academic year. Often, these students try to balance competing priorities such as residency applications, away rotations, and other clinical duties, leaving less time for engagement in advocacy work. A future opportunity would be to present the breadth of content regarding SDH during the preclinical years and then to explore topics in more depth during the clinical years.

With the goal of supporting preparation to better attend to SDH as part of patient care, students ideally would be partnered with an advocacy mentor (either a resident or faculty member) with a similar interest during their first year. This strategy would also help as a longitudinal way to evaluate students' knowledge and engagement in advocacy following didactic training. Glassick's six standards of quality scholarship include clear goals, adequate preparation, appropriate methods, significant results, effective presentation, and reflective critique.27 Incorporation of SDH and advocacy toward the end of clinical training hardly allows time for the full application of these conceptual frameworks. Furthermore, this type of educational approach may be more meaningful than an objective measure such as the PAAQ. For example, students could be observed during their clinical skills courses or clinical rotations to evaluate how they incorporate their knowledge of SDH into real-world patient encounters.

Another alternative would include a student experience similar to the educator training, where learners visit local community sites and speak to local advocacy experts about pertinent issues. This approach would permit an assessment of whether students could identify key stakeholders within an area of interest to allow for appropriate preparation and partnership for change. Additionally, this strategy would let students directly observe how SDH impact patients and families in real-life settings. Students then could be required to complete a small project and presentation (with close mentorship) demonstrating that they understand how to advocate about these social inequities. To assess the longitudinal and practical impact of this approach, it would also be helpful to survey graduating fourth-year medical students to inquire about their level of community involvement, self-reflection, and plans for further engagement during residency and beyond.

Our findings may have limited generalizability due to a single site of implementation, and future research should expand this work at multiple sites. The advocacy lecture could easily be adapted to fit pediatric clerkships at other academic institutions, and other fields (e.g., family medicine, internal medicine, surgery) could develop and implement similar content pertaining to their specialties.

In settings where pediatric residents are not available, the lecture could be given by faculty or other medical educators. We would encourage institutions to select educators with an understanding of SDH, passion for advocacy, and prior experience in planning and implementing community-based projects, as mentioned above in the Lecture Implementation section. A subset of the questions is locally specific (e.g., rate of food insecurity in our city, specific advocacy examples from our institution) but could be adapted to fit other communities/institutions or omitted altogether.

In summary, as recognition of the importance of advocacy and SDH increases, the development of educational tools for teaching this information becomes more necessary. Our lecture was able to produce an improvement in knowledge of these topics and, more importantly, was well received by students. Early introduction to advocacy and SDH during relevant clinical rotations emphasizes the importance of these topics and may establish a foundation for advocacy as part of routine patient care.

Appendices

A. Lecture Presentation.pptx

B. Pediatric Advocacy Assessment Questionnaire.docx

C. Student Feedback Form.doc

D. Answer Key.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Erin Boger, pediatric clerkship coordinator, for her assistance with the implementation of this lecture and with data collection. We would also like to thank the pediatric residents of Wake Forest Baptist as well as the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools, the Forsyth County Department of Public Health, World Relief Triad, the NC Refugee Health Program, the Wake Forest Department of Family and Community Medicine, the Program in Community Engagement of the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, the Carolinas Collaborative (funded by the Duke Endowment), and Imprints Cares.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Prior Presentations

Marsh M, McLaurin-Jiang S. Teaching advocacy in pediatrics. Presented at: QI Showcase, Wake Forest School of Medicine; May 2017; Winston-Salem, NC.

Marsh M, McLaurin-Jiang S. Teaching advocacy in pediatrics. Presented at: North Carolina Pediatric Society Annual Meeting; August 2017; Asheville, NC.

Marsh M, McLaurin-Jiang S. Teaching advocacy in pediatrics. Presented at: Section on Child Abuse and Neglect (SOCAN) for the American Academy of Pediatric Society Meeting; September 2017; Chicago, IL.

Ethical Approval

Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Council on Community Pediatrics. Community pediatrics: navigating the intersection of medicine, public health, and social determinants of children's health. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):623–628. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3933 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo AA, Thomas PA, Chilton LA, Mascola L; Council on Community Pediatrics, Section on Epidemiology, Public Health, and Evidence. Pediatricians and public health: optimizing the health and well-being of the nation's children. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20173848 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e296–e304. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long JA, Lee RS, Federico S, Battaglia C, Wong S, Earnest M. Developing leadership and advocacy skills in medical students through service learning. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(4):369–372. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182140c47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel J, Coleman DL, James T. Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):159–162. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rezet B, Risko W, Blaschke GS; for Anne E. Dyson Community Pediatrics Training Initiative Curriculum Committee. Competency in community pediatrics: consensus statement of the Dyson Initiative Curriculum Committee. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4)(suppl 3):1172–1183. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2825O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones M, Buttenheim AM, Salmon D, Omer SB. Mandatory health care provider counseling for parents led to a decline in vaccine exemptions in California. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(9):1494–1502. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright CJ, Katcher ML, Blatt SD, et al. Toward the development of advocacy training curricula for pediatric residents: a national Delphi study. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(3):165–171. https://doi.org/10.1367/A04-113R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman BD, Rose J, Best D, et al. The Community Pediatrics Training Initiative project planning tool: a practical approach to community-based advocacy. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10630 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson JM, Albertini LW. Caring for children with chronic health care needs: an introductory curriculum for pediatric residents. MedEdPORTAL. 2012;8:9172 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9172 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belkowitz J, Sanders LM, Zhang C, et al. Teaching health advocacy to medical students: a comparison study. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(6):E10–E19. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Relman AS. What medical graduates need to know but don't learn in medical school. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1990;3(1S):49–S-53-S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung EK, Kahn SR, Altshuler M, Lane JL, Plumb JD. The JeffSTARS Advocacy and Community Partnership Elective: a closer look at child health advocacy in action. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10526 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain LJ, Sanders LM, Takayama JI. Child advocacy training: curriculum outcomes and resident satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(9):842–847. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.9.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerber L, Mahoney JF, Gold P. Lived experience and patient advocacy module: curriculum and faculty guide. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10617 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald M, West J, Israel T. From identification to advocacy: a module for teaching social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10266 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10266 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hufford L, West DC, Paterniti DA, Pan RJ. Community-based advocacy training: applying asset-based community development in resident education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):765–770. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a426c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croft D, Jay SJ, Meslin EM, Gaffney MM, Odell JD. Is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1165–1170. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826232bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berns RM, Tomayko EJ, Cronin KA, Prince RJ, Parker T, Adams AK. Development of a culturally informed child safety curriculum for American Indian families. J Prim Prev. 2017;38(1-2):195–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0459-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis E, Sabnis S, Hamilton C, et al. Improving immunization rates through community-based participatory research: Community Health Improvement for Milwaukee's Children program. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2016;10(1):19–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2016.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilchrist J, Parker EM. Racial and ethnic disparities in fatal unintentional drowning among persons less than 30 years of age—United States, 1999–2010. J Safety Res. 2014;50:139–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyetunji TA, Stevenson AA, Oyetunji AO, et al. Profiling the ethnic characteristics of domestic injuries in children younger than age 5 years. Am Surg. 2012;78(4):426–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredrick N. Teaching social determinants of health through mini-service learning experiences. MedEdPORTAL. 2011;7:9056 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9056 [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIntosh S, Block RC, Kapsak G, Pearson TA. Training medical students in community health: a novel required fourth-year clerkship at the University of Rochester. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):357–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181668410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Child Health Initiative website. https://www.childhealthinitiative.org/ Accessed November 30, 2018.

- 27.Glassick CE, Huber MT, Maeroff GI. Scholarship Assessed: Evaluation of the Professoriate. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Lecture Presentation.pptx

B. Pediatric Advocacy Assessment Questionnaire.docx

C. Student Feedback Form.doc

D. Answer Key.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.