Abstract

Rationale: Bilateral lung transplantation is widely used to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial lung disease (ILD), on the basis of an expectation of improved survival after transplantation. Yet, waiting list mortality is higher while awaiting bilateral transplantation. The net effect of procedure preference on overall survival is unknown.

Objectives: To determine whether an unrestricted procedure preference is associated with improved overall outcomes after listing for lung transplantation.

Methods: We performed a retrospective cohort study of 12,155 adults with COPD or ILD listed for lung transplantation in the United States between May 4, 2005, and December 31, 2014. We defined a “restricted” procedure preference as listing for “bilateral transplantation only” and an “unrestricted” procedure preference as listing for any combination of bilateral or single lung transplantation. We used a composite “intention-to-treat” primary outcome that included events both before and after transplantation, defined as the number of days between listing and death, removal from the list for clinical deterioration, or retransplantation.

Results: In adjusted analyses, an unrestricted procedure preference was associated with a 3% lower rate of the primary intention-to-treat outcome in COPD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89–1.07) and a 1% higher rate in ILD (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.94–1.08). There was no convincing evidence that these associations varied by age, disease severity, or the use of mechanical support. Among those with ILD and concomitant severe pulmonary hypertension, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 17% increased rate of the primary outcome (aHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.99–1.39). An unrestricted preference was consistently associated with lower rates of death or removal from the list for clinical deterioration and with higher rates of transplantation. Graft failure rates were similar among those listed with restricted and unrestricted preferences.

Conclusion: When considering outcomes both before and after transplantation, we found no evidence that patients with COPD or ILD benefit from listing for bilateral lung transplantation compared with listing for a more liberal procedure preference. An unrestricted listing strategy for suitable candidates may increase the number of transplants performed without impacting overall survival.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung transplantation

Lung transplantation is a potentially life-saving treatment option for adults with advanced lung diseases, such as interstitial lung disease (ILD), cystic fibrosis (CF), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Yet, the scarcity of donor lungs limits the number of people who can undergo lung transplantation. In 2016, there were only 2,327 lung transplant procedures performed in the United States, despite more than 100,000 adults living with ILD (1), 30,000 with CF (2), and millions with COPD (3). Although efforts to increase donor availability have been successful (4–10), the waiting list mortality rate in the United States increased from 11.1 to 15.1 deaths per 100 wait-list years between 2005 and 2015 (11). Strategies that further increase donor lung supply could substantially improve access to lung transplantation.

Approximately 75% of lung transplant surgeries in the United States are bilateral procedures using two lungs from the same donor (11). Some patients must undergo bilateral transplantation to remove diffuse bronchopulmonary infection (as in CF) or to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension. However, for patients with COPD or ILD—accounting for 83% of lung transplant procedures performed in the United States in 2016 (11)—both single (unilateral) and bilateral transplantation are options. In 2016, 69% of patients with COPD and 63% of patients with ILD undergoing transplantation received two lungs (11). Although listing preference may be influenced by many factors, the decision to perform bilateral or single lung transplantation is ultimately made by transplant center personnel, who base their decisions on anecdotal experience and studies that have inconsistently identified post-transplant survival benefits for bilateral transplantation (12–16). Wider use of single lung transplantation, however, could increase transplantation rates by transplanting two recipients with lungs from a single donor. A simulation study found that a universal single lung transplant policy for candidates with COPD would result in 4.2% fewer waiting list deaths among all waiting list candidates (17).

To date, few studies have examined “intention-to-treat” outcomes in lung transplantation (i.e., the inclusion of survival time and events that occur both before and after transplantation) (18). Because intention-to-treat outcome measures capture the entirety of the patient experience after placement on the waiting list, examination of these outcomes can capture unique center performance metrics (18) and may yield important clinical insights above and beyond those provided by studies restricted to either pre- or post-transplant outcomes. We used nationwide U.S. transplant registry data to test the hypothesis that an unrestricted listing preference (listing for any combination of bilateral and single lung transplantation) would be associated with improved outcomes, defined using a composite intention-to-treat outcome (including events before and after transplantation) compared with those listed using a restricted or bilateral only preference.

Methods

Study Design, Participants, and Data Sources

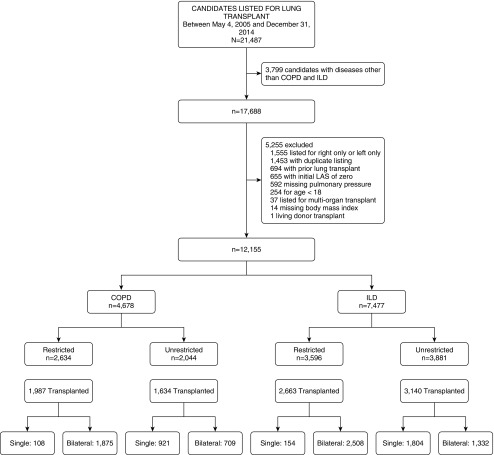

We performed a retrospective cohort study of adults with COPD or ILD aged 18 years or older placed on the waiting list for lung transplantation in the United States between May 4, 2005 and December 31, 2014 using data provided by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network with follow-up through September 9, 2016. We excluded those listed for right single lung transplant only or left single lung transplant only, those missing pulmonary artery pressure or body mass index (BMI), those listed with a lung allocation score (LAS) of zero, those listed for multiorgan transplantation or retransplantation, those listed at multiple centers, or those who underwent living donor transplantation (Figure 1). For each participant, only the first instance of placement on the waiting list was included. All data were obtained from Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, including demographic, clinical, and outcome data. The study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of informed consent.

Figure 1.

Study flow. Type of transplant performed is missing on eight subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (four restricted, four unrestricted) and five subjects with interstitial lung disease (ILD) (one restricted, four unrestricted). LAS = lung allocation score.

Measurements

The primary exposure was the transplant center’s requested “lung preference” for each candidate at the time of placement on the waiting list. Transplant centers request one or more donor lung preference for each candidate, determining which donor lungs are ultimately offered to the candidate. In some cases, centers opt for a preference for bilateral lung offers only. For the purposes of this analysis, we refer to this as a “restricted” preference. Centers can also select a preference for (i.e., a willingness to consider) either a right or a left single lung offer. In practice, this means there are six additional possible preferences (excluding lobar and combined heart–lung transplantation): 1) single left lung only, 2) single right lung only, 3) single left or right lung only, 4) bilateral or single left lung only, 5) bilateral or single right lung only, and 6) bilateral or either single lung. If a donor has only one suitable lung for transplantation (e.g., contralateral pneumonia or trauma), this lung would not be offered to candidates with a restricted preference but could be offered to those with a less-restrictive preference. We excluded those listed for single left lung only or single right lung only and combined the remaining four categories (any combination of bilateral and single lung transplantation) into an “unrestricted” preference category.

The composite intention-to-treat primary outcome was the number of days from placement on the waiting list until death (before or after transplantation), removal from the waiting list for clinical deterioration, or retransplantation. We right-censored survival time for those still alive on the last day of follow-up. Secondary outcomes included time to transplantation, time to death on the waiting list or removal from the waiting list, and 1-year and 5-year graft failure.

Analysis Approach

To examine associations between lung preference and the composite primary intention-to-treat outcome, we constructed mixed-effects stratified Cox regression models separately for those with COPD and ILD, with transplant center as a random effect. Because there is substantial variation in waiting list time, the expected increase in mortality that occurs in the early post-transplant period will occur at different follow-up times for each individual, easily leading to violation of the proportional hazards assumption. To avoid this, we used a stratified Cox model allowing us to include both pre- and post-transplant survival in the same model (see Figure E1 in the online supplement) (19). One stratum included survival time on the waiting list. The other stratum included survival time after transplantation. Subjects who received a transplant were included in both strata; subjects who did not undergo transplantation were only included in the waiting list stratum. During the analysis stage of the study, we noted that waiting list survival curves for restricted and unrestricted strategies intersected at 1,000 days for COPD and 1,850 days for ILD, violating the proportional hazards assumption only within the waiting list time stratum. This violation was addressed by including an interaction term between preference and time in sensitivity analyses. Only 4% of study participants had waiting times beyond these time points. There was no violation of the proportional hazards assumption in the post-transplant survival stratum.

We included variables for age, sex, race, BMI, height, ABO blood group, and LAS at listing in our multivariable models, because these variables defined a minimal set that closed back-door paths using a directed acyclic graph (Figure E2). The LAS is a priority score used for lung allocation, with higher numbers indicating greater disease severity and higher priority for transplantation. In secondary analyses, we included LAS, pulmonary artery pressure, mechanical support (mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal support), and BMI as time-varying covariates to adjust for these variables at both listing and transplantation. We also tested for effect modification by age, LAS, pulmonary hypertension, and use of mechanical support. Effect estimates come from fully adjusted models that included the interaction term. We plotted Kaplan-Meier survival estimates without statistical hypothesis testing.

To estimate the strength of an unmeasured (negative) confounder needed to suppress an association between lung preference and the primary outcome, we performed quantitative assessments of bias by calculating “non-null E-values” (20). E-values range from 1 to infinity, with larger values indicating that an unmeasured confounder would need to have stronger associations with both the exposure and outcome in fully adjusted models to alter the effect estimate. We chose to calculate non-null E-values for a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.5, the magnitude of benefit of bilateral transplantation in a previous study (14).

To examine associations between lung preference and secondary waiting list outcomes, we constructed Fine and Gray multivariable-adjusted competing risk models for the subdistributions of the competing risks of death/delisting for clinical deterioration and transplantation (21). We compared crude cumulative incidence curves using Gray’s test (21).

To examine associations between lung preference and the secondary outcomes of 1- and 5-year graft failure after transplantation, we constructed mixed-effects Cox regression models with center as a random effect. These models included adjustment for recipient factors at transplantation (age, sex, race, BMI, height, ABO blood group, mechanical support, LAS, and mean pulmonary artery pressure) and donor factors (age, sex, BMI, height, alcohol use, smoking, pulmonary infection, diabetes, arterial oxygen partial pressure, and cause of death). The most recent mean pulmonary artery pressure was used if none was recorded at transplantation (n = 228). We used multiple imputation with chained equations in 10 datasets using the “mi” command in STATA for missing covariate data.

All statistical hypothesis tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of 0.05. Analyses were performed in STATA/IC version 14.2 (StataCorp, LP) and R version 3.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using the CMPRSK (22), SURVMINER (23), SURVIVAL (24), EValue (25), and COXME (26) packages.

Results

Study Participants

There were 12,155 candidates placed on the lung transplant waitlist during the study period who met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The median age was 59 years, 43% were women, and 62% had ILD. The median LAS at listing was 36.7. A total of 49% were listed with an unrestricted preference (44% of those with COPD and 52% of those with ILD). Temporal trends in the relative distribution of listing preferences were generally stable between 2005 and 2014 (Figure E3). A total of 78% underwent transplantation during the study period, with bilateral transplantation more commonly performed among those with a restricted preference (Table E1, Figure 1).

Those listed with an unrestricted preference tended to be older, more frequently white and less likely to have severe pulmonary hypertension (Table 1). The median LAS and use of mechanical support at listing were similar between restricted and unrestricted preferences. We did not observe a relationship between center volume and the proportion of waiting list candidates listed with a restricted preference (Figure E4).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 12,155 U.S. lung transplant candidates at the time of placement on the waiting list

| Characteristic | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

Interstitial Lung Disease |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted Preference (n = 2,634) | Unrestricted Preference (n = 2,044) | Restricted Preference (n = 3,596) | Unrestricted Preference (n = 3,881) | |

| Age, yr | 58 (52–62) | 61 (57–65) | 56 (48–62) | 62 (56–66) |

| Male | 1,296 (49) | 938 (46) | 2,128 (59) | 2,549 (66) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 2,269 (86) | 1,849 (90) | 2,450 (68) | 3,117 (80) |

| Black | 256 (10) | 158 (8) | 645 (18) | 276 (7) |

| Hispanic | 69 (3) | 21 (1) | 367 (10) | 348 (9) |

| Other | 40 (2) | 16 (1) | 134 (4) | 140 (4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.3 (21.3–27.9) | 24.5 (21.5–27.8) | 27.1 (23.9–30.1) | 27.7 (24.7–30.1) |

| Height, cm | 168 (162–175) | 168 (160–175) | 170 (163–178) | 172 (163–178) |

| ABO blood type | ||||

| A | 1,020 (39) | 852 (42) | 1,327 (37) | 1,502 (39) |

| AB | 116 (4) | 85 (4) | 123 (3) | 140 (4) |

| B | 311 (12) | 198 (10) | 427 (12) | 425 (11) |

| O | 1,187 (45) | 909 (44) | 1,719 (48) | 1,814 (47) |

| Lung allocation score | 33 (32–35) | 33 (32–34) | 43 (37–54) | 41 (37–50) |

| Lung allocation score quartile | ||||

| <35 | 2,022 (77) | 1,757 (86) | 529 (15) | 635 (19) |

| 35–45 | 544 (21) | 264 (13) | 1,539 (43) | 1,839 (54) |

| 45–55 | 29 (1) | 10 (1) | 648 (18) | 680 (20) |

| >55 | 39 (1) | 13 (1) | 880 (24) | 727 (22) |

| Use of mechanical support | 29 (1) | 16 (1) | 178 (5) | 139 (4) |

| Pulmonary hypertension (mean PA pressure) | ||||

| None (<25 mm Hg) | 1,194 (45) | 1,019 (50) | 1,288 (36) | 2,238 (58) |

| Mild (25–34 mm Hg) | 714 (27) | 567 (28) | 596 (17) | 811 (21) |

| Moderate (34–44 mm Hg) | 370 (14) | 299 (15) | 509 (14) | 420 (11) |

| Severe (>44 mm Hg) | 356 (14) | 159 (8) | 1,203 (33) | 412 (11) |

| Procedure preference | ||||

| Bilateral only (restricted) | 2,634 (100) | 0 (0) | 3,596 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Bilateral or single right or left lung | 0 (0) | 994 (48) | 0 (0) | 1,967 (51) |

| Single right or left lung | 0 (0) | 617 (30) | 0 (0) | 1,136 (29) |

| Bilateral or single right lung | 0 (0) | 263 (13) | 0 (0) | 283 (8) |

| Bilateral or single left lung | 0 (0) | 170 (8) | 0 (0) | 495 (15) |

Definition of abbreviation: PA = pulmonary artery.

Data are median (interquartile range) and frequency (percentage). Mechanical support defined as the use of mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal support. Percentages may not exactly equal 100% because of rounding.

Among the 9,424 who underwent transplantation, those listed with an unrestricted preference tended to be older, with lower LAS scores, and tended to have lower pulmonary artery pressure (Table E1). Donor lung quality was similar between groups (Table E1).

Composite Intention-to-Treat Outcome in COPD

Among those with COPD, 958 (47%) of those listed with an unrestricted preference, and 1,106 (42%) of those listed with a restricted preference met the primary intention-to-treat outcome during 9,572 and 7,816 person-years of follow-up, respectively. Among those with an unrestricted preference, 179 (9%) died on the waiting list, 733 (45%) died after transplantation, and 46 (2%) underwent retransplantation. Among those with a restricted preference, 321 (12%) died on the waiting list, 757 (38%) died after transplant, and 28 (1%) underwent retransplantation.

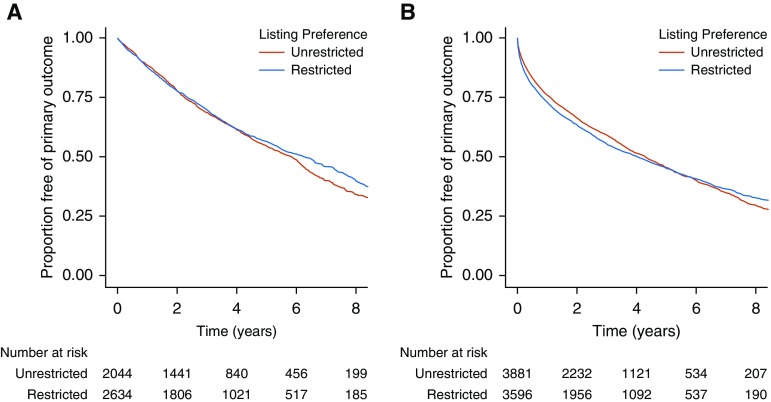

In an unadjusted mixed-effects stratified Cox model, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 6% reduction in the rate of the composite primary intention-to-treat outcome (HR, 0.94; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86–1.03; P = 0.17; Table 2, Figure 2A). In a fully adjusted model, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 3% reduction in the rate of the primary outcome (adjusted HR [aHR], 0.97; 95% CI, 0.89–1.07; P = 0.60; Table 2). After inclusion of time-varying values for LAS, mean pulmonary artery pressure, mechanical support, and BMI, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 5% decreased rate of the primary outcome (aHR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.86–1.05; P = 0.29; Table E2). Results were similar for those listed less than 1,000 days (n = 4,708; aHR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97–1.16; P = 0.21; Table E3). Among those listed for longer than 1,000 days, an unrestricted preference was associated with an increased rate of the primary outcome (n = 461; aHR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.07–2.85).

Table 2.

Associations between lung preference and outcomes among 12,155 lung transplant candidates

| Outcome | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

Interstitial Lung Disease |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | Unrestricted | P Value | Restricted | Unrestricted | P Value | |

| Composite primary intention-to-treat outcome | ||||||

| No. listed | 2,634 | 2,044 | 3,596 | 3,881 | ||

| No. of events | 1,106 | 958 | 1,862 | 1,995 | ||

| Event rate (95% CI)* | 11.6 (10.9–12.3) | 12.3 (11.5–13.1) | 18.0 (17.2–18.8) | 17.5 (16.7–18.3) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | 0.17 | 1 | 1.01 (0.94–1.07) | 0.87 |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)† | 1 | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) | 0.60 | 1 | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.77 |

| Death on the waiting list or delisting‡ | ||||||

| No. of events | 321 | 179 | 728 | 591 | ||

| Event rate (95% CI)* | 11.9 (10.7–13.3) | 9.1 (7.8–10.5) | 41.0 (38.1–44.1) | 37.0 (34.2–40.1) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 0.70 (0.59–0.84) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.73 (0.65–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)§ | 1 | 0.59 (0.47–0.73) | <0.001 | 1 | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Transplantation | ||||||

| No. undergoing transplant | 1,987 | 1,634 | 2,663 | 3,140 | ||

| Event rate (95% CI)* | 73.6 (70.4–76.9) | 82.6 (78.7–86.7) | 149.7 (144.1–155.5) | 196.8 (190.0–203.8) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | <0.001 | 1 | 1.21 (1.15–1.28) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)§ | 1 | 1.33 (1.22–1.44) | <0.001 | 1 | 1.22 (1.14–1.30) | <0.001 |

| Graft failure at 1 yr | ||||||

| No. of events | 240 | 207 | 430 | 504 | ||

| Event rate (95% CI)* | 13.5 (11.8–15.2) | 14.1 (12.3–16.2) | 18.3 (16.7–20.1) | 18.1 (16.6–19.8) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio | 1 | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) | 0.95 | 1 | 1.01 (0.88–1.15) | 0.93 |

| Fully adjusted hazard ratio|| | 1 | 1.00 (0.81–1.22) | 0.98 | 1 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | 0.19 |

| Graft failure at 5 yr | ||||||

| No. of events | 662 | 624 | 997 | 1,212 | ||

| Event rate (95% CI)* | 11.3 (10.5–12.2) | 12.9 (11.9–14.0) | 14.2 (13.4–15.0) | 18.3 (16.7–20.1) | ||

| Unadjusted hazard ratio | 1 | 1.14 (1.01–1.27) | 0.03 | 1 | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | 0.04 |

| Fully adjusted hazard ratio|| | 1 | 1.10 (0.98–1.24) | 0.11 | 1 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.89 |

Definition of abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Hazard ratios for secondary outcomes (death/delisting and transplantation) represent subdistribution hazard ratios from competing risks regression models.

Expressed as rate per 100 person-years.

Adjusted for lung allocation score at listing, ABO blood group, height, age, sex, race, body mass index at listing, with listing center as a random effect.

Death or delisting for clinical deterioration.

Adjusted for lung allocation score at listing, ABO blood group, height, age, sex, race, body mass index at listing, and listing center.

Adjusted for recipient characteristics at time of transplantation (lung allocation score, ABO blood group, height, age, sex, race, body mass index) and donor characteristics (age, body mass index, sex, height, alcohol use, history of cigarette use, pulmonary infection, diabetes, arterial oxygen pressure on 100% fraction of inspired oxygen), with listing center as a random effect.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the composite primary intention-to-treat outcome (time from listing until death before or after transplantation, removal from the waiting list due to clinical deterioration, or retransplantation) among those with (A) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and (B) interstitial lung disease. Numbers below each panel are the number of subjects at risk at each time point.

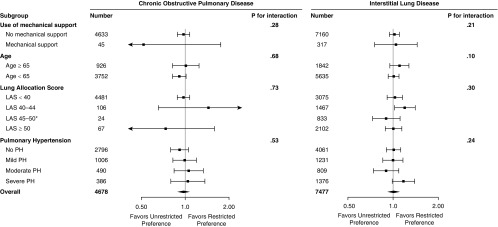

Stratified analyses are shown in Figures 3 and E5 and Table E4. There was no strong evidence of effect modification by age, LAS, mechanical support, or pulmonary hypertension (P for interaction ≥ 0.20). However, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 9% reduction in the rate of the primary intention-to-treat outcome among those younger than 65 years old (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.82–1.01; P = 0.09) and among those without pulmonary hypertension (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.80–1.05; P = 0.21) in adjusted models. Sample sizes were small (<100) among those receiving mechanical support and those with LAS scores greater than 45. We did not observe meaningful associations between an unrestricted preference and the primary outcome within any subgroup (Figures 3 and E5; Table E4).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of multivariable-adjusted associations between lung preference and the composite primary intention-to-treat outcome by prespecified stratification variables. *Small number of events among subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with lung allocation score (LAS) between 45 and 50 precludes analysis. Mechanical support = mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal support; PH = pulmonary hypertension.

Composite Intention-to-Treat Outcome in ILD

Among those with ILD, 1,995 (51%) with an unrestricted preference and 1,862 (52%) with a restricted preference met the primary intention-to-treat outcome during 11,405 and 10,363 person-years of follow-up, respectively. Among those with an unrestricted preference, 591 (15%) died on the waiting list, 1,295 (41%) died after transplantation, and 109 (3%) underwent retransplantation. Among those with a restricted preference, 728 (20%) died on the waiting list, 1,065 (40%) died after transplantation, and 69 (3%) underwent retransplantation.

In an unadjusted mixed-effects stratified Cox model, we did not detect a meaningful association between an unrestricted preference and the primary intention-to-treat outcome (HR 1.01; 95% CI, 0.94–1.07; P = 0.87; Table 2, Figure 2B). Findings were similar in a fully adjusted model (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI,0.94–1.08; P = 0.77; Table 2). Inclusion of time-varying covariates for LAS, mean pulmonary artery pressure, mechanical support, and BMI produced similar results (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.94–1.09; P = 0.77; Table E2). Findings were similar among those listed less than 1,850 days (n = 7,432; aHR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.96–1.11; Table E3). Among those listed more than 1,850 days, there was a lower rate of the primary outcome for those listed with an unrestricted preference with a wide CI that included the null value (n = 45; aHR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.15–1.90).

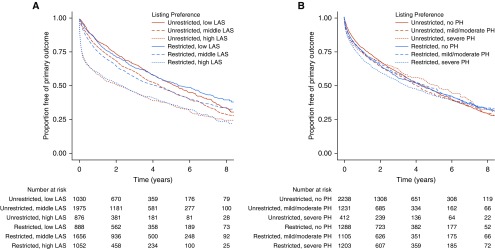

Stratified analyses are shown in Figures 3, 4, and S6 and Table E4. In fully adjusted models, we found no significant interactions between lung preference and use of mechanical support, LAS, or pulmonary hypertension (P for interaction ≥ 0.20). Although there was modest statistical evidence of effect modification by age (P for interaction = 0.10), effect estimates were similar across strata (Figure 3, Table E4). Among those with severe pulmonary hypertension, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 17% increased rate of the primary outcome (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.99–1.39; P = 0.07; Figure 3, Table E4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the composite primary intention-to-treat outcome (time from listing until death before or after transplantation, removal from the waiting list because of clinical deterioration, or retransplantation) among participants with interstitial lung disease (ILD) stratified by (A) lung allocation score (LAS), and (B) severity of pulmonary hypertension (PH). Numbers below each panel are the number of subjects at risk at each time point. Low LAS = listing LAS within the lowest tertile of listing LAS for this cohort; middle LAS = listing LAS within the middle tertile of listing LAS for this cohort; high LAS = listing LAS within the highest tertile of listing LAS for this cohort; mild PH = mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 25 but <30; moderate PH = mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 30 but <35; severe PH = mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥ 35.

Quantitative Assessment of Bias

The non-null E-values required to move the HRs in the primary analyses to 1.5 were 2.1 for COPD and 2.0 for ILD. As a comparison, among those with ILD, severe pulmonary hypertension was associated with a 1.8-fold increased likelihood of being listed with a restricted preference (Table E5). Other indications were less strongly associated (Table E5).

Secondary Outcomes: Waiting List Mortality and Transplantation Rate

An unrestricted preference was consistently associated with lower rates of death or removal from the list for clinical deterioration while on the waiting list and with higher rates of transplantation (Tables 2, E6, and E7, Figure S7).

Secondary Outcome: Graft Failure

There were no meaningful associations between lung preference and 1-year graft failure after transplantation among those with either COPD or ILD (Table 2, Figure E7). Among those with COPD, an unrestricted preference was associated with a 10% higher rate of graft failure at 5 years (aHR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.98–1.24; P = 0.11). There was no significant association between lung preference and 5-year graft failure in ILD (Table 2, Figure E8).

Among those who underwent transplantation, there was no meaningful association between single lung transplantation and graft failure at 1 year for COPD (aHR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.79–1.25; P = 0.96) or ILD (aHR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.87–1.18; P = 0.86). However, single lung transplantation was associated with increased rates of graft failure at 5 years for both COPD (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.09–1.42; P = 0.001) and ILD (aHR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04–1.27; P = 0.008; Table E8).

Discussion

We were unable to detect meaningful associations between procedural listing preference and intention-to-treat survival outcomes after placement on the lung transplant waiting list in a contemporary cohort of U.S. adults with COPD or ILD. Those listed for bilateral lung transplantation only had similar overall outcomes compared with those listed for a less-restrictive combination of bilateral and single lung transplantation. With the possible exception of patients with ILD with severe pulmonary hypertension, this observation held true even among the most severely ill patients, including those with a high LAS and those using mechanical support as a bridge to transplantation. Consistent with prior work, a less restrictive preference was associated with a lower waiting list mortality rate and a higher transplantation rate in ILD (27, 28). This study extends those findings to COPD (27, 29, 30). In short, we failed to find any substantial benefit to restricting patients with COPD or ILD to a bilateral transplant procedure.

Our findings have important implications for clinical care and health policy. More than two-thirds of patients with ILD and COPD undergoing lung transplantation in the United States receive two lungs. Because each bilateral transplant deprives another patient of a single lung transplant, physicians appear to be favoring beneficence over equitable allocation of this scarce resource. This practice is driven in part by prior observational studies suggesting that bilateral transplantation may confer a survival advantage when compared with single lung transplantation, particularly for ILD (12, 14–16). In addition, transplant centers can lose accreditation if their 1-year post-transplant survival rate decreases substantially (31). Our findings suggest that the tacit calculus favoring bilateral transplantation does not promote beneficence and may instead lead to harm and injustice by failing to offer transplantation to those in need. Clinicians may wish to more widely adopt a practice of single lung transplantation, because overall outcomes do not differ by preference, and, as in kidney transplantation, one donor can provide allografts for two recipients. Transplant center accreditors should consider holding transplant centers equally accountable for both pre- and post-transplant outcomes.

In our analytic approach, we gave equal weight to deaths occurring before and after transplantation. Because, in most cases, transplantation is expected to improve one’s quality of life, it may have been appropriate to place greater value on post-transplant survival time, which would have tended to favor an unrestricted listing preference, because this strategy increases transplantation rates and decreases waiting list mortality rates. In light of this, and because transplantation is intended to both prevent waiting list mortality and prolong overall survival, we assert that our approach is both appropriate and conservative.

We performed an observational study of treatment effect. Such studies are particularly prone to confounding by indication for treatment (32), and, therefore our findings should be interpreted with care. There is a paucity of data describing the specific patient characteristics that lead clinicians to list patients for bilateral transplantation. Although our data suggest that bilateral lung transplantation is the preferred procedure for patients who are younger and sicker, the influence of these (and other) factors is likely to vary by center. Because greater disease severity leads to worse outcomes both before and after lung transplantation, unmeasured clinical indications for a restricted preference could have suppressed a true effect, thereby biasing toward the (largely) null effect estimates that we detected. Although our findings may be “suppressed” by indication, we adjusted for usual indications for a restricted preference, and our quantitative assessment of bias suggests that only a strong unmeasured suppressor would mask a true beneficial effect. An E-value of 2 indicates that there must be a substantially strong unmeasured factor that leads to at least a twofold increased likelihood of being listed with a restricted preference while at the same time reducing the risk of death by at least 50%. The nature of this unmeasured suppressor—if it exists—is unclear. And, even if a restricted preference were to result in somewhat better outcomes, an unrestricted listing strategy could increase the number of transplants performed, thereby saving more lives. In addition, data on additional indications for bilateral lung transplantation, such as chronic lung infection, anatomic abnormalities, pleural disease, diaphragm dysfunction, pulmonary nodules, and prior chest surgery, were not available to us. Clinicians should continue to incorporate judgement, experience, and patient-specific characteristics into their clinical decision making. Other limitations include the mismeasurement of transplant registry variables and low power in some stratified analyses.

In summary, our findings suggest equipoise between restricted and unrestricted lung transplant listing preferences for patients with COPD or ILD. Increased use of unrestricted preferences could increase transplantation rates without having a major impact on overall survival. Federal entities should consider incorporating waiting list outcomes in their assessment of transplant center performance, and clinicians should consider waiting list outcomes when choosing a listing preference for their patients, because doing so maximizes both individual and societal good.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants T32 HL105323, R01 HL114626, and K24 HL131937, and Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the view or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: A.T. and D.J.L.; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: all authors; first draft: M.R.A. and A.T.; drafting or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: A.R. primarily; final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Nalysnyk L, Cid-Ruzafa J, Rotella P, Esser D. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: review of the literature. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:355–361. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall B, Elbert A, Petren K, Rizvi S, Fink A, Ostrenga J, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry 2015 annual data report Bethesda, MD: 2016. [accessed 2018 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.cff.org/Our-Research/CF-Patient-Registry/2015-Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet. 2007;370:765–773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cypel M, Yeung JC, Liu M, Anraku M, Chen F, Karolak W, et al. Normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion in clinical lung transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1431–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angel LF, Levine DJ, Restrepo MI, Johnson S, Sako E, Carpenter A, et al. Impact of a lung transplantation donor-management protocol on lung donation and recipient outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:710–716. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-432OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somers J, Ruttens D, Verleden SE, Cox B, Stanzi A, Vandermeulen E, et al. A decade of extended-criteria lung donors in a single center: was it justified? Transpl Int. 2015;28:170–179. doi: 10.1111/tri.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigemura N, Horai T, Bhama JK, D’Cunha J, Zaldonis D, Toyoda Y, et al. Lung transplantation with lungs from older donors: recipient and surgical factors affect outcomes. Transplantation. 2014;98:903–908. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meers C, Van Raemdonck D, Verleden GM, Coosemans W, Decaluwe H, De Leyn P, et al. The number of lung transplants can be safely doubled using extended criteria donors; a single-center review. Transpl Int. 2010;23:628–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaney J, Suzuki Y, Cantu E, III, van Berkel V. Lung donor selection criteria. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:1032–1038. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.03.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis BD, Norton HJ, Jacobs DG The Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative. The Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative: has it made a difference? Am J Surg. 2013;205:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valapour M, Lehr CJ, Skeans MA, Smith JM, Carrico R, Uccellini K, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 annual data report: lung. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:363–433. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thabut G, Christie JD, Ravaud P, Castier Y, Dauriat G, Jebrak G, et al. Survival after bilateral versus single-lung transplantation for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:767–774. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss ES, Allen JG, Merlo CA, Conte JV, Shah AS. Survival after single versus bilateral lung transplantation for high-risk patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaffer JM, Singh SK, Reitz BA, Zamanian RT, Mallidi HR. Single- vs double-lung transplantation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis since the implementation of lung allocation based on medical need. JAMA. 2015;313:936–948. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thabut G, Christie JD, Ravaud P, Castier Y, Brugière O, Fournier M, et al. Survival after bilateral versus single lung transplantation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective analysis of registry data. Lancet. 2008;371:744–751. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60344-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan D, Karanam AB, Merlo A, Tom Bozzay PA, Zucker MJ, Seethamraju H, et al. Post-transplant survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients concurrently listed for single and double lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:657–660. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munson JC, Christie JD, Halpern SD. The societal impact of single versus bilateral lung transplantation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1282–1288. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0695OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maldonado DA, RoyChoudhury A, Lederer DJ. A novel patient-centered “intention-to-treat” metric of U.S. lung transplant center performance. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:226–231. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinbaum D, Klein M. Survival analysis, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. Recurrent event survival analysis; pp. 363–423. [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:268–274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray B.cmprsk: subdistribution analysis of competing risks. R package version 2.2-7. 2014[accessed 2018 Dec 15]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cmprsk

- 23.Kassambara I, Kosinski M.survminer: drawing survival curves using ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.4.1. 2017[accessed 2018 Dec 15]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer

- 24.Therneau TM.A package for survival analysis in S. Version 2.38. 2015[accessed 2018 Dec 15]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival

- 25.Mathur MB, VanderWeele TJ. R function for additive interaction measures. Epidemiology. 2018;29:e5–e6. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Therneau TM.coxme: mixed effects Cox models. R package version 2.2-7. 2018[accessed 2018 Dec 15]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=coxme

- 27.Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, Burton NA, Barnett SD, Edwards E. Comparison of wait times and mortality for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients listed for single or bilateral lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Oliveira NC, Osaki S, Maloney J, Cornwell RD, Meyer KC. Lung transplant for interstitial lung disease: outcomes for single versus bilateral lung transplantation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:263–267. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivr085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Rogers CA, Bonser RS, Banner NR, Demiris N, Sharples LD UK Cardiothoracic Transplant Steering Group. Assessing the benefit of accepting a single lung offer now compared with waiting for a subsequent double lung offer. Transplantation. 2011;91:921–926. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821060b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borro JM, Delgado M, Coll E, Pita S. Single-lung transplantation in emphysema: retrospective study analyzing survival and waiting list mortality. World J Transplant. 2016;6:347–355. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; hospital conditions of participation: requirements for approval and re-approval of transplant centers to perform organ transplants. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2007;72:15197–15280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miettinen OS. The need for randomization in the study of intended effects. Stat Med. 1983;2:267–271. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780020222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.