Abstract

Objective:

To examine situations where shared decision making (SDM) in practice does not fit the ideal of patient-centered decision making.

Methods:

We explore circumstances in which elements necessary to realize SDM – patient readiness to participate and understanding of the decision – are not present. We consider the influence of contextual factors on decision making.

Results:

Patients’ preference and readiness for participation in SDM are influenced by multiple interacting factors including the patients’ comprehension of the decision, their emotional state, the strength of their relationship with the clinician, and the nature of the decision. Uncertainty often inherent in information can lead to misconceptions and ill-formed opinions that impair patients’ understanding. In combination with cognitive biases, these factors may result in decisions that are incongruent with patients’ preferences. The impact of suboptimal understanding on decision making may be augmented by the context.

Conclusions:

There are circumstances in which basic elements required for SDM are not present and therefore the clinician may not achieve the goal of patient centered decision making.

Practice Implications:

A flexible and tailored approach that draws on the full continuum of decision making models and communication strategies is required to achieve patient-centered decision making.

Keywords: Shared decision making, decisional agency, patient engagement, healthcare setting

1. Introduction

Shared decision making (SDM) is a collaborative process in which patients and providers make decisions together, integrating patient values and preferences with clinical evidence. Respect for patient values and preferences and their incorporation into clinical decisions is a core feature of both SDM and patient-centered care. As such, SDM has been hailed as the pinnacle of patient-centered care [1]. Despite its promise, SDM has been surprisingly hard to achieve in practice. Numerous studies have identified barriers to SDM, and documented that decision making in the “real world” often falls short of the ideal in which the patient is an active participant with a good understanding of the options and clearly formed values and preferences who works with a clinician with adequate time, knowledge and willingness to share the decision [2–5].

Fundamental to most SDM models is the assumption that the patient is informed about the decision and thereby understands not only that there is a decision to be made, but also understands and is able to evaluate the options and their associated risks, benefits and uncertainties [6]. In fact, in some circumstances, patients may not achieve such an understanding. As a result, they may prefer to defer the decision to the clinician, or they may be ill-prepared or unready to participate in the decision. In other cases, the patient may feel they understand the issues and have reached a decision, and only want to share it with the clinician to inform them of their choice. The patient, the clinician and the decision making process are all affected by the specific context, which we define as including the decision characteristics and the broader healthcare setting. These contextual factors may amplify or minimize the effects of the patient not fully understanding or being ready to grapple with the options. For these and other reasons, the decision making process may unfold in a manner apparently at variance with an idealized view of SDM. This may be unavoidable and in fact such deviations may sometimes be necessary to achieve patient-centered decision making, which we posit as the ultimate goal.

This paper reports on a symposium on SDM, which took place at the 2017 International Conference on Communication in Healthcare, in Baltimore, Maryland. The symposium considered the importance of patient involvement and understanding as fundamental to SDM. It explored whether and how clinicians should respond when one or more of the key elements necessary for SDM – patient desire to participate in a decision or patient understanding of the decision and the options – are not present. Symposium speakers were chosen with the intent of bringing together diverse views of individuals working in the field of SDM on issues that remain challenging and in need of further consideration. The goal was to be provocative and stimulate discussion, rather than to address each topic definitively. To that end, presentations were brief and limited to exposition of key issues, allowing ample time for audience discussion. A rich dialogue ensued, with attendees contributing comments that were captured in the form of detailed notes. Key themes were extracted and organized into sections according to the presentation topics. One additional domain emerged during the discussion that had not been included as a presentation, but is included below as ‘The Health Care System, Policy and Culture’.

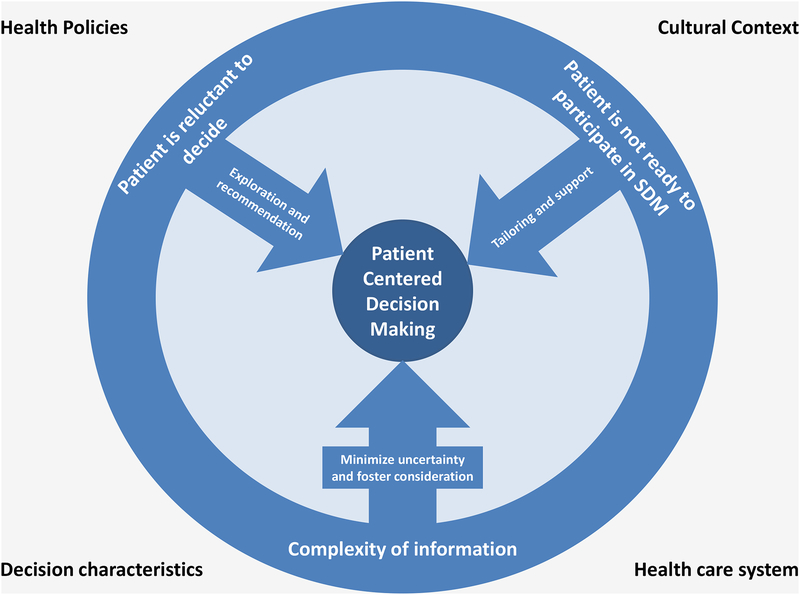

The goal of this manuscript is to explore specific circumstances in which the elements necessary to realize SDM are absent, making it challenging in practice to apply SDM in a manner that is consistently patient-centered. We explore the challenges these circumstances present for clinicians and patients through synthesis of the symposium presentations and subsequent discussion and offer suggestions of how to keep the patient in the center of decision making when these circumstances arise (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Keeping the patient in the center of decision making – overcoming common challenges in the practice of shared decision making.

2. When patients prefer not to decide.

Patient preference for involvement in decision making is arguably one of the strongest determinants of whether SDM will be patient-centered. Clinicians who recognize the value of SDM and seek to integrate this approach into their practice may therefore find it extremely challenging when the patient says, “What would you do doc?” or “Doc, you’re the expert, I just want you to decide”. How clinicians approach this challenge varies widely (box) [7], and often falls short of enacting a patient-centered, shared decision process.

Why do some patients not fully embrace participating in a decision involving their own health and health care? Some patients may choose to make an informed choice of a clinician who they then expect to make the best choices on their behalf, particularly for specialized treatment. Patients’ preferences for participating in a decision are related to many factors, including their knowledge and comprehension of the decision and the options involved [8]. Some of the strongest evidence for this comes from the Cochrane review of decision aids where patients in the control arm (i.e., those who did not have access to decision aids) preferred to defer decisions to the physician about 25% of the time compared to only 13% of those exposed to a decision aid [9]. Thus, as patients gain a better understanding of the decision and the underlying tradeoffs, they tend to prefer a more active role in decisions. In short, willingness and self-efficacy for participating in decision making, at least for some patients, is a state and not a trait. Although increased understanding may promote patient willingness to participate in decision making, other characteristics associated with patients’ preferring a less active decision-role may not be modifiable. It is therefore likely that many patients will be reluctant to participate in at least some decisions, at least some of the time. Providers need to be equipped with the skills to engage patients in SDM when patients are willing, and to take other approaches when patients may not want to participate in SDM.

In some cases, patients may not be the only reluctant participants in SDM. The real-world examples of how clinicians in practice approach patients who prefer not to decide (box) demonstrate that not all clinicians have the tools and skills needed to fully embrace sharing decisions with patients. Clinician training is one means of equipping clinicians with the skills required to do this. However, not all clinicians will have the interest, time or resources to acquire these skills. Therefore, non-clinician decision tools are also needed to support SDM. Decision aids are the best known and studied, with evidence from a Cochrane review that includes 105 trials demonstrating that decision aids routinely lead to better-informed decision making that may be more consistent with patients’ values [9]. Another approach to engaging clinicians in SDM is to design strategies that help clinicians have better conversations with their patients. One example of this is a communication strategy that prompts surgeons to present surgical outcomes as the best case, worst case, and most likely case [10]. A full array of support tools and strategies may help to fully engage patients and providers in advancing towards the ideal of SDM.

Recommendations.

We recommend that clinicians confronted with patients who prefer not to decide work to keep the patient at the center by respecting the patient’s preference and seeking to provide a recommendation that is aligned with the patient’s goals and values. It may be helpful to treat reluctance to engage in a decision as a “conversation starter”. That is, the clinician could convey respect for the patient’s preference by saying “I’m happy to make a recommendation for you…”. Such a statement will also reassure the patient that they are not alone and that they will not be burdened with an overwhelming decision. However, to assure that the recommendation is aligned with the patient’s goals and values, the clinician could follow up with “…and before I make a recommendation, I’d like to just understand a little more about what is important to you. Would that be okay?” To the extent that a patient’s reluctance to participate in SDM may relate to inadequate information, the clinician could also inquire, “Before I make a recommendation for you, are there questions about the options I can help to address?” A response of this nature confirms the clinician’s respect for the patient’s decisional role preferences while also creating an opportunity to assure that a recommendation is aligned with the patient’s goals and values. Such a response may also help to maintain trust and strengthen the relationship. An important final step is to check that the patient understands the key elements of the decision and its implications for their care [11].

3. When patients are willing but not ready to share a decision.

Knowledge of the decision and understanding of the choices involved are necessary ingredients for patient involvement in SDM. However, they are insufficient for patients to be well equipped or well supported or ready to engage in SDM. Patients have reported a variety of barriers to becoming involved in decision making processes, including time and how care is organized, cognitive and affective characteristics of the patient, and the patient’s relationship with the clinician [2]. In short, patients’ readiness to engage in SDM is related to their knowledge, their emotional state, and the power balance with their clinician.

When looking at the most relevant steps in SDM processes, patients’ ability to engage in the decision process is expected to depend on the following elements: 1) being aware that a decision needs to be made and motivated to participate in decision making, 2) being sufficiently able to process and integrate information into evaluations, 3) being sufficiently able to communicate with the clinician, and 4) being aware of where one stands in the decision process and of what one needs [12]. The elements are a function of patient characteristics, such as age, health literacy and emotional state, and of the decision situation, such as decision complexity and time available to make a decision. The key elements are to a large extent variable or amenable to change. That is, being ready to engage in a SDM process is not a given, nor is it a psychological trait. It may vary from one situation to another. For example, a patient may be ready to engage in SDM with his general practitioner about prostate cancer screening, but not with his oncologist about hormone treatment for prostate cancer after he has just been told that his cancer has spread. This difference in readiness may not only result from the differences in decision-related characteristics, but also from fluctuations in patient characteristics and the interaction between decision- and patient-related characteristics. The patient with prostate cancer may experience more emotional distress when he needs to decide about hormone treatment compared to his emotional reaction to considering screening, which may make it more difficult for him to digest the information and to be active during the consultation. The influences of patient and decision-related characteristics can also interact with those of the clinician and significant others involved, and within the particular healthcare context. For example, the patient may feel more ready to engage in SDM with his general practitioner with whom he has a longstanding relationship, but less ready with his new oncologist.

Recommendations.

We recommend that clinicians start by assessing the patient’s readiness to be engaged in SDM soon after it is clear that there is a decision to be made. This may be particularly challenging given the complex and dynamic nature of patient readiness. Patients’ ability to understand and manipulate information and express a preference could be used as initial indicators of readiness. If the patient does not appear ready, efforts may be focused on the element or elements of readiness that seem most relevant. That is, efforts may be directed at making the patient aware of the need to make a decision by making it more explicit. If the patient appears confused or to be having difficulty grasping the necessary information, efforts should focus on making the information more comprehensible for the patient, on allowing the patient time to consider the options or to consult others. If the patient appears emotionally overwhelmed or distressed, efforts should focus on providing emotional support to help alleviate high levels of distress. With permission from the patient, it may also be helpful to engage family member(s) who can promote patient readiness by providing emotional support and helping to obtain clarifying information when needed. If genuine attempts to overcome barriers to patient readiness fail, the clinician may need to consider a different decision making approach.

4. When challenges related to information processing and decision making get in the way

A central premise of SDM is that by involving patients in this process, their values and preferences will be carefully balanced with information about options, resulting in a patient-centered decision. However, several contextual factors related to the available information and potential biases in the processing of information make it difficult to achieve this ideal. First, evidence regarding the expected risks and harms of treatment approaches is often complicated and incomplete, and expert recommendations may be conflicting. Expecting laypersons to navigate this uncertainty may be burdensome and may impair their ability to participate in decision making. Presenting more information or options in itself can make decisions more difficult [13–16]. Simply raising an issue with a patient can easily be misinterpreted as an endorsement; patients do not expect clinicians to bring up interventions that are not in their best interests. Second, exposure to numerous sources of medical information that may be less evidence-based, including social networks, media campaigns, powerful anecdotes, and social norms can lead to misconceptions and ill-informed opinions [17–19]. Thirdly, it has been well-established that human decision making is subject to multiple biases, including biases related to how information is presented, such as order of presentation, loss- vs. gain-based framing, and anchor effects, and what information is presented, such as confirmation bias [20–25]. Use of common and natural decision strategies such as shortcuts or heuristics to simplify complicated decisions may lead to suboptimal choices [26–28]. Finally, patients do not always have well-defined and articulated values and preferences to incorporate into medical decisions. Especially for new or complex decisions, patients need time to consider information and develop their preferences [29]. In some cases, patients may even construct preferences to justify their choices, rather than the other way around. For all these reasons, the model of SDM in which impartial presentation of evidence and solicitation of preferences, even done “ideally,” often fails, resulting in decisions that may not be consistent with patients’ values.

The challenges inherent in many aspects of the SDM process – ensuring patients are adequately informed and understand the options, combating misconceptions and ill-informed opinions, encouraging thorough consideration instead of heuristic processing, and clarifying unformed preferences – ask for alternative communication strategies beyond simple unbiased information provision. Some authors, using labels like “informed advocacy” and “beneficent persuasion”, have suggested that, when there is evidence supporting a normative decision, advocacy should be combined with unbiased presentation of information [30,31]. These situations may not always typify the preference-sensitive decisions for which SDM is most relevant. However, these models recognize that most medical decisions do not conform to the idealized model of informed, autonomous choice [32]. In practice, patients often receive recommendations regarding preference-sensitive choices, with little opportunity to deliberate about options or even recognize that multiple options may exist. In other cases, patients faced with a new decision situation tend to quickly develop an early preference for an option or may focus on only a few attributes. As a result, they may not consider alternatives as thoroughly as would be ideal [29]. In these cases, “persuasive messaging” to encourage patients to fully consider alternatives may be “normatively correct.” In a trial of “persuasive decision aids,” more participants changed their minds about mammography and prostate cancer screening preferences after viewing a persuasive decision aid, as compared to more traditional, knowledge-focused materials [33]. The implications of these findings for SDM might seem controversial; however, in practice, many patients will need persuasion simply to engage with a decision or to consider a recommendation to weigh the options and make a personal choice.

Recommendations.

As in the case of patients who prefer not to participate or are not ready to participate in SDM, we recommend that clinicians assess the patient’s understanding as a means of identifying misconceptions that may lead to an ill-informed decision. How clinicians handle this situation when it inevitably arises will depend on the potential consequences of an ill-informed decision. If the decision circumstances allow, multiple conversations may be needed to shape the patient’s understanding. Clinicians should also consider the range of communication options available to achieve patient-centered decision making. This is not limited to attempts at unbiased presentation of information but may also require advocacy and persuasive messaging.

5. The Decision as Contextual Factor

An important thread throughout the above discussion is that one of the things that makes it impossible to use a single, “one size fits all” approach to patient-centered decision making is that the details of the decision process and the challenges that arise are highly dependent on the decision of interest. We expect that every reader of this paper can imagine decisions that he or she might prefer to leave to an expert clinician and that he or she might not be ready to face due to emotional distress or insufficient understanding. It may be harder to imagine decisions where biases might cloud our judgment, but hindsight may help to reveal such instances. The point is that the details of the decision (e.g., urgency, complexity, reversibility) and of the associated options (e.g., their harms, benefits and uncertainties) all influence how decision making unfolds. These decision characteristics may influence patient willingness and readiness to participate in decision making and even the likelihood of the patient having misconceptions about the decision or specific options. For instance, patients may prefer to defer a decision with great uncertainty – where the evidence is conflicting, and experts disagree – to their clinician. Urgent or emergent decisions may not allow sufficient time for the patient to become ready to fully engage in SDM. These decision characteristics illustrate the need for a flexible view of patient-centered decision making.

Recommendations.

We suggest that clinicians tailor their SDM approach to the patient and the decision context. There well may be decision characteristics that will prevent patients from being willing or ready to participate in SDM, despite efforts to provide comprehensible information and address barriers to readiness. In these cases, it is important to keep in mind the goal of SDM - to make a decision that is aligned with the patient’s values and preferences. If clinicians clarify the patient’s values and preferences and ensure patients are informed about the decision and the options, they are still sharing the deliberation aspect of the decision, even if the clinician ultimately provides a strong recommendation for the actual decision.

6. The Health Care System, Policy and Culture

The broader context for decision making, including the organization of the healthcare system, health policies, and cultural factors, can all influence how decision making occurs in practice. For example, it has been shown that patient preferences for participation in decision making differ between patients from East and West Germany, illustrating the influence of culture on patient willingness to share decisions [34]. There are also cultural differences in whether specific decisions are shared. This is apparent in differences in end-of-life decision making across countries. In some European countries, it is considered overly burdensome to place responsibility for decisions to limit life-sustaining measures on families of critically ill patients, leading to a tendency for a paternalistic approach to these decisions [35,36]. By contrast, inthe United States (U.S.), these decisions are frequently left to the family with input and recommendations from clinicians. It has been suggested that placing family members in a decisional role that is incongruent with their expectations may increase their risk of psychological distress following critical illness [37–39]. Thus, cultural factors may influence patient preferences and expectations regarding their role in decision making. Failure to account for cultural factors and differences may impose an undue burden on patients and their families. In this way, SDM would not be patient-centered.

The healthcare setting may also influence patient and provider readiness and ability to engage in SDM. Patients have reported several features of healthcare organizations that impede participation in SDM. These include lack of continuity of care, short visit duration, and difficulty arranging multiple visits to allow for multiple conversations [2]. Many of these factors can also make it more difficult for providers to engage in SDM with patients, with insufficient time the most oft-cited provider-level organizational barrier [5]. These organizational barriers may in turn exacerbate the challenge faced by clinicians when fundamental elements necessary for SDM – patient preference to participate and understanding of the decision and options – are not present. Overcoming these organizational barriers could conceivably expand the situations in which SDM may be patient-centered.

SDM is often conceptualized as a conversation occurring primarily within the doctor-patient dyad. Expanding this view to involve other types of health practitioners holds great promise for enhancing the process of SDM. Health educators, nurses, and therapists bring a complementary set of skills to those of physicians and are therefore well positioned to serve as “decision coaches” [40]. In this capacity, they may be able to overcome barriers to patient readiness or preference to engage in SDM. Although this inter-professional team-based approach is promising, it also faces organizational barriers including defining individual roles and responsibilities, ensuring continuity, and the need for time and space to interact as a team [41].

Health policies and legislation also influence the degree to which specific decisions will be shared. Vaccine laws in the U.S. mandate specific vaccinations for school-age children and healthcare workers, except in cases of exemptions [42]. These laws appropriately recognize the public health relevance of vaccination and favorable balance of benefits and harms and supersede SDM where it would not be appropriate. In other cases, strong recommendations from expert panels could be used to influence policies and clinicians to avoid non-beneficial care, rather than relying on SDM to avoid overutilization. Examples of this include the Swiss Medical Board’s recommendation against new systematic mammography screening programs [43], and the Choosing Wisely Campaign adopted by the American Board of Medicine in the U.S. It is important to distinguish these approaches from SDM, as they require alternate communication strategies. For example, an announcement approach in which clinicians make a brief statement that assumes readiness for vaccination increases human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage compared to an open-ended conversation communication strategy [44]. Such approaches do not preclude the need for patients to be informed, autonomous, or for their preferences to be considered.

Recommendations.

Approaches to patient-centered decision making should consider the influence of healthcare delivery, policies, and culture on patient preferences and expectations regarding participation in decision making. Incorporating these differences in communication skills training programs will help clinicians recognize the need for a nuanced approach to SDM. Structural changes to overcome organizational barriers to patient and clinician participation in SDM are also needed. Policy tools that might promote necessary organizational changes to support SDM could include development of measures of organizational support for SDM and mechanisms to incentivize providers and organizations to make the necessary organizational changes. Finally, careful consideration should be given to systematically identifying decisions where legislation or strong expert recommendations may appropriately shift the decision making approach from SDM to a clinician-advocacy or societally mandated approach.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

7.1. Discussion

We have described contextual factors that influence whether SDM is truly patient-centered. Some of these factors, such as patient preference to take a less active role and lack of readiness to participate in decision making may be modifiable. In these cases, efforts to address these factors are warranted and could expand the circumstances in which SDM is patient-centered. However, it is important to also recognize that some patients may persist in preferring a less active role despite efforts to engage them in the decision making process. In other cases, barriers to patient readiness, such as emotional distress, may not be modifiable in the timeframe in which a decision is required. In these instances, other approaches beyond SDM may be required to achieve patient-centered decision making. Given the dynamic nature of many of these contextual factors, the biggest challenge in practice may be determining the most patient-centered decision making approach on a spectrum ranging from a very directive approach, through SDM, to a patient informing the clinician of a decision they have made on their own.

Practical tools and strategies are needed to help clinicians efficiently ascertain patient preferences regarding decision making, address modifiable factors, and identify which decisions are appropriate to be shared. It would be helpful to incorporate the complementary perspectives of patients, clinicians, caregivers and communications experts during the development of such tools and strategies. Patients have expertise in their awareness of the decision, feelings of being informed and comfortable communicating with their clinicians, as well as their preferences for participation. Clinicians have medical expertise and experience discussing decisions with patients. Patients’ family members and caregivers have valuable experience supporting patients through the decision process, while communication experts can help identify ways to enhance the effectiveness of clinician-patient interactions.

7.2. Conclusion

SDM offers tremendous potential for achieving patient-centered care. However, implementing SDM with a “one-size fits all” approach without considering specific contextual factors will not necessarily achieve this goal. When fundamental elements necessary for SDM – patient desire to participate in the decision process, understanding of the decision and options, and stable patient preferences – are not present, a flexible, patient-centered decision making approach is required. Ideally, this would involve use of an array of decision tools, supports, communication strategies, and an inter-professional team to promote patient understanding and participation. In cases when these supports are insufficient or unable to achieve patient readiness in the timeframe the decision requires, it is important to acknowledge and consider alternative models of decision making and use precise terminology because different approaches to decision making warrant different communication strategies. More work is needed to determine which decision making approach best fits a given set of circumstances, and to develop tools and communication strategies to support the full spectrum of decision making models.

7.3. Practice implications

Clinicians should consider the full range of decision making models and the contextual factors that influence which is most patient-centered. Awareness of the patient- and decision-related characteristics that can affect patients’ engagement in SDM may help clinicians to identify and meet the decisional needs of individual patients. Adopting a broader patient-centered decision making view may overcome clinician resistance to SDM by allowing for alternative approaches as indicated by the circumstances.

Funding

This study was supported by grant 1K08HS024596 (Dr. Fisher) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- [1].Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N.Engl.J.Med 2012;366:780–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ.Couns 2014;94:291–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, Stobbart L, Tomson D, Macphail S, Dodd C, Brain K, Elwyn G, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ 2017;357:j1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zeuner R, Frosch DL, Kuzemchak MD, Politi MC. Physicians’ perceptions of shared decision-making behaviours: a qualitative study demonstrating the continued chasm between aspirations and clinical practice. Health Expect. 2015;18:2465–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Légaré F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ.Couns 2008;73:526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ.Couns 2006;60:301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Matlock DD, Nowels CT, Masoudi FA, Sauer WH, Bekelman DB, Main DS, Kutner JS. Patient and cardiologist perceptions on decision making for implantable cardioverterdefibrillators: a qualitative study. Pacing Clin.Electrophysiol 2011;34:1634–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ.Couns 2006;60:102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst.Rev 2017;4:CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schwarze ML, Taylor LJ. Managing Uncertainty - Harnessing the Power of Scenario Planning. N.Engl.J.Med 2017;377: 206–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Politi MC, Dizon DS, Frosch DL, Kuzemchak MD, Stiggelbout AM. Importance of clarifying patients’ desired role in shared decision making to match their level of engagement with their preferences. BMJ 2013;347:f7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ.Couns 2015; 98: 1172–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Jewett JJ. Informing consumer decisions in health care: implications from decision-making research. Milbank Q. 1997;75:395–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peters E, Dieckmann N, Dixon A, Hibbard JH, Mertz CK. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med.Care Res.Rev 2007;64:169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Angott AM, Ubel PA. The benefits of discussing adjuvant therapies one at a time instead of all at once. Breast Cancer Res.Treat 2011;129:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Fagerlin A, Ubel PA. A demonstration of “less can be more” in risk graphics. Med.Decis.Making 2010;30:661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nimmon L, Regehr G. The Complexity of Patients’ Health Communication Social Networks: A Broadening of Physician Communication. Teach.Learn.Med 2017:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics?. Med.Decis.Making 2005;25:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychol.Bull 2001;127:267–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A,. Judgment under uncertainty : heuristics and biases / edited by Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic, Amos Tversky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kahneman D, Tversky A,. Choices, values, and frames. New York Cambridge, UK: Russell sage Foundation ; Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schwartz B,. The paradox of choice: why more is less. New York: Ecco, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. “If I’m better than average, then I’m ok?”: Comparative information influences beliefs about risk and benefits. Patient Educ.Couns 2007;69:140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J.Natl.Cancer Inst 2011;103:1436–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Payne John W.,. The adaptive decision maker : hardback. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tversky A, Sattath S, Slovic P. Contingent weighting in judgment and choice. Psychological Review 1988;95:371–384. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gigerenzer G, Brighton H. Homo heuristicus: why biased minds make better inferences. Top.Cogn.Sci 2009;1: 107–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pieterse AH, de Vries M, Kunneman M, Stiggelbout AM, Feldman-Stewart D. Theory-informed design of values clarification methods: a cognitive psychological perspective on patient health-related decision making. Soc.Sci.Med 2013;77:156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bekker HL. Decision aids and uptake of screening. BMJ 2010;341:c5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Swindell JS, McGuire AL, Halpern SD. Beneficent persuasion: techniques and ethical guidelines to improve patients’ decisions. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Swindell JS, McGuire AL, Halpern SD. Shaping patients’ decisions. Chest 2011;139:424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Saver BG, Mazor KM, Luckmann R, Cutrona SL, Hayes M, Gorodetsky T, Esparza N, Bacigalupe G. Persuasive Interventions for Controversial Cancer Screening Recommendations: Testing a Novel Approach to Help Patients Make Evidence-Based Decisions. Ann Fam Med 2017;15:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hamann J, Bieber C, Elwyn G, Wartner E, Horlein E, Kissling W, Toegel C, Berth H, Linde K, Schneider A. How do patients from eastern and western Germany compare with regard to their preferences for shared decision making?. Eur.J.Public Health 2012;22:469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, Cassell J, Cox P, Hill N, Hinds C, Pimentel JM, Reinhart K, Thompson BT. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU. Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:770–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Moselli NM, Debernardi F, Piovano F. Forgoing life sustaining treatments: differences and similarities between North America and Europe. Acta Anaesthesiol.Scand 2006;50:1177–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larche J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B, FAMIREA Study Group. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am.J.Respir.Crit.Care Med 2005;171:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Passive decision-making preference is associated with anxiety and depression in relatives of patients in the intensive care unit. J.Crit.Care 2009;24:249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gerritsen RT, Hofhuis JGM, Koopmans M, van der Woude M, Bormans L, Hovingh A, Spronk PE. Perception by family members and ICU staff of the quality of dying and death in the ICU: a prospective multicenter study in The Netherlands. Chest 2013;143:357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stacey D, Murray MA, Légaré F, Dunn S, Menard P, O’Connor A. Decision Coaching to Support Shared Decision Making: A Framework, Evidence, and Implications for Nursing Practice, Education, and Policy. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2008;5:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, Dunn S, Pluye P, Frosch D, Kryworuchko J, Elwyn G, Gagnon MP, Graham ID. Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J.Eval.Clin.Pract 2011;17:554–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Barraza L, Schmit C, Hoss A. The Latest in Vaccine Policies: Selected Issues in School Vaccinations, Healthcare Worker Vaccinations, and Pharmacist Vaccination Authority Laws. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 2017;45:16–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Biller-Andorno N, Juni P. Abolishing mammography screening programs? A view from the Swiss Medical Board. N.Engl.J.Med 2014;370:1965–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements Versus Conversations to Improve HPV Vaccination Coverage: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2017;139:1764 Epub 2016 Dec 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]