Abstract

Background

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-EC) is one of the main antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. Little data are available on how biofilm formation (BF) contributes to EC-caused bloodstream infection (BSI) in cancer patients. This study investigated the impact of BF on clinical outcomes of cancer patients with EC-caused BSI.

Methods

Clinical outcome and microbiological characteristics including the presence of bla genes in ESBL-EC isolates were retrospectively collected from BSI cancer patients. Patients infected with ESBL-EC were compared with patients infected with third-generation cephalosporin-susceptible strains. Survival curves were generated by Kaplan–Meier analysis and the survival difference was assessed by the log-rank test. Risk factors for ESBL-EC infection, predictors of mortality, and outcome differences were determined by multivariate logistic regression and Cox regression analysis, respectively.

Results

A high prevalence of ESBL-EC with dominant blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-15 plus blaTEM-52 genotype was found in BSI cancer patients. Independent risk factors for infection with ESBL-EC were cephalosporins, chemotherapy, and BF. Metastasis, ICU admission, BF-positive ESBL-EC, organ failure, and the presence of septic shock were revealed as predictors for mortality. The ESBL characteristic was associated with the BF phenotype, and the overall mortality was significantly higher in cancer patients with BF-positive ESBL-EC-caused BSI.

Conclusion

blaCTX-M-15 type ESBL-EC is highly endemic among cancer patients with BSI. BF is associated with multi-drug resistance by ESBL-EC and is also an independent risk factor of mortality for cancer patients with BSI. Our findings suggest that the combination of BF-positive ESBL-EC isolates with other appropriate laboratory indicators might benefit infection control and improve clinical outcomes.

Keywords: biofilm formation, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, Escherichia coli, bloodstream infection

Introduction

Bloodstream infection (BSI) is one of the most severe forms of nosocomial infection, especially in immunocompromised cancer patients. Escherichia coli (EC) is a common cause of BSI, and production of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) is the main mechanism conferring resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, which results in treatment problems, higher morbidity, mortality, and increased health care costs.1 Previous studies showed that biofilm formation (BF) is associated with resistance of EC toward antimicrobial drugs, and BF markedly increases the incidence of health care-associated infections, especially in catheter-related BSI.2–5 One study indicated that 60.2% of EC strains were multi-drug resistant (MDR, maximum resistance to ampicillin), and 43% of MDR EC had a biofilm-positive phenotype.2 BF results in serious clinical problems because of its resistance to host defense systems and to conventional antimicrobial therapy, which substantially hinders various treatments. Although many studies reported that BF is closely associated with EC-caused urinary tract infections,2,6,7 more recent studies indicated that bacterial BF might act as a direct triggering factor contributing to cancer initiation and progression. For example, in colorectal cancer experimental models, biofilm microbial populations can significantly impair the intestinal epithelial barrier function, alter poly-amine metabolism affecting cellular proliferation, enhance pro-inflammatory/pro-oncogenic responses, and exacerbate intestinal dysbiosis.8 The invasive and co-aggregation capacity of microbiota may be essential for biofilm-promoted colon tumorigenesis. In addition, some studies attributed BF-related mortality to certain debatable factors, such as drugs with no activity against BF, biofilm heterogeneity, and the presence of comorbidities.7,9 However, to our knowledge, there is little information about how BF contributes to EC-caused BSI, especially to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-EC)-caused BSI in cancer patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the impact of BF-positive, EC-caused BSI on the clinical outcome of hospitalized cancer patients.

Methods

Setting and study design

A retrospective study was conducted at the Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (http://www.tjmuch.com/, http://www.tjmuch.com/zlyjs/) between January 2013 and September 2017. All hospitalized cancer patients with the first episode of BSI were included in the study. Cancer patients with polymicrobial BSI, under the age of 18, or with non-EC-caused BSI were excluded from the study. Data retrospectively collected included age, sex, associated diseases, sources of BSI, invasive procedures, such as urinary catheterization or tracheostomy during the preceding 3 months, multiple shot antibiotics therapy during the preceding 3 months, the presence of severe sepsis or septic shock, and in-hospital mortality.

Depending on the different requirements, cancer patients included in this study were divided into the following groups: patients with BSI due to an isolate of ESBL-EC and those with non-ESBL-EC-caused BSI. The two groups were compared in order to identify independent risk factors for ESBL-EC infection. Patients who died were further compared with those who survived to determine predictors for mortality. Furthermore, the outcome differences between BF-positive and BF-negative EC-infected patients or ESBL-EC-infected patients were assessed.

Definition

All cases of cancer were confirmed by pathology. The BSI assessment of whether the isolated organisms represent true BSI, rather than contamination, was made based on the clinical or laboratory evidence of infection: fever, hypothermia, evidence of localized infection, inadequate organ perfusion, severe sepsis, and leukocytosis. The definitions of severe sepsis and septic shock were adapted from the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference Committee.10 The source of BSI was determined according to the definition of nosocomial infections by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the presence of clinical signs with EC isolation from the presumed source.11 MDR was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories. Once a species has intrinsic resistance to certain antimicrobial agents, related antimicrobial classes are not counted when calculating the number of classes to which the isolate is resistant.11 In-hospital mortality was defined as death by any cause within the first 30 days after the onset of BSI during hospitalization.

Microbiological procedures

Blood cultures (8–10 mL blood from a patient) inoculated in BACTEC plus aerobic/F and anaerobic lytic/10 vials, were incubated using the automated blood culture system (BACTEC FX400; Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) at 35°C for at least 5 days. Positive cultures were determined with gram staining, and then subcultured on both blood agar and MacConkey plates (JinZhangKeji, Tianjin, China) at 35°C for 18–24 hours. Pathogens identification and susceptibility tests were performed on the Vitek 2 Compact automated microbiology system (BioMerieux, Craponne, France) by using GN and GN67 cards. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute criteria were used to define the susceptibility or the resistance to antimicrobial agents.12

ESBL screening, confirmatory test, and gene detection

Bacterial isolates identified as EC, were stored on glycerol tryptic soy broth in a –20°C freezer. When a fresh seed-stock vial was required, it was removed and used to inoculate a series of working cultures.

The VITEK 2 Compact was used to screen ESBL-EC. The ESBL confirmatory test was performed using cefotaxime (CTX, 30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg) alone, or in combination with clavulanate (10 µg) on Mueller-Hinton agar.12 Strains producing ESBL were confirmed by ≥5 mm increments in zone diameter. EC ATCC25922 (the negative control) and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 (the positive ESBL producer) (American Type Culture Collection, USA) were used for quality control.

Detection of ESBL genotype-related gene families (blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M) was performed using PCR with primers (Table S1) and conditions previously described.13–15 PCR amplification for the individual bla gene was carried out in a Thermal Cycler (T100, Bio-Rad). A negative control (nuclease-free water) was included in each run. PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, and finally visualized in a gel documentation system (ChemiDoc XRS, Bio-Rad). Purified PCR products were sequenced (Sangon Biotech), and the sequencing results were forwarded for bioinformatics analysis using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool online program (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

BF detection

Crystal violet staining was performed in 96-well plates with all EC isolates sampled.16 For each EC isolate, a single colony was incubated in test tubes containing 5 mL of Luria–Bertani (LB) medium and then shake-cultured at 37°C for 18 hours. Then, 1 mL of bacterial suspension was trans-inoculated into a new test tube containing 5 mL of sterile LB medium. Each well of the sterile 96-well flat-bottomed plastic tissue culture plate with a lid was filled with 200 µL of bacterial suspension. Negative controls (blank) were LB broth alone, which was dispensed into eight wells per tray. After aerobic incubation at 37°C for 24 hours, the content of the wells was carefully drawn off and each well was washed three times with 250 µL of sterile physiological saline. Biofilms were stained with 0.2 mL of crystal violet (2%) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Unspecific staining in the wells was rinsed out three times with PBS. The plates were inverted on a towel, allowed to air dry, and the dye-stained adherent cells in each well were dissolved with 200 µL 30% acetic acids. The OD of re-solubilized crystal violet in each well was measured at a wavelength of 590 nm absorbance. All tests were carried out three times, with three wells per culture, and the results were averaged (cutoff value is 0.218; Table S2).

Statistical analyses

The mean and SD were calculated for continuous variables. Continuous variables with normal distribution were compared with the Student’s t-test, and variables that were not normally distributed were compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. The chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. All statistically significant variables with P<0.05 identified in the univariate analysis were further analyzed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. OR and 95% CI were calculated. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to generate survival curves, and the difference between the survival curves was assessed by mean of the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis for the predictors of survival was performed. All significant variables related to mortality in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model for further analysis. All analyses were performed using the SPSS version 23.0 software. Two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered to have statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital. Waiving of informed consent was obtained due to the retrospective noninterventional study design. Data were collected anonymously.

Results

Risk factors of ESBL-EC-caused BSI in cancer patients

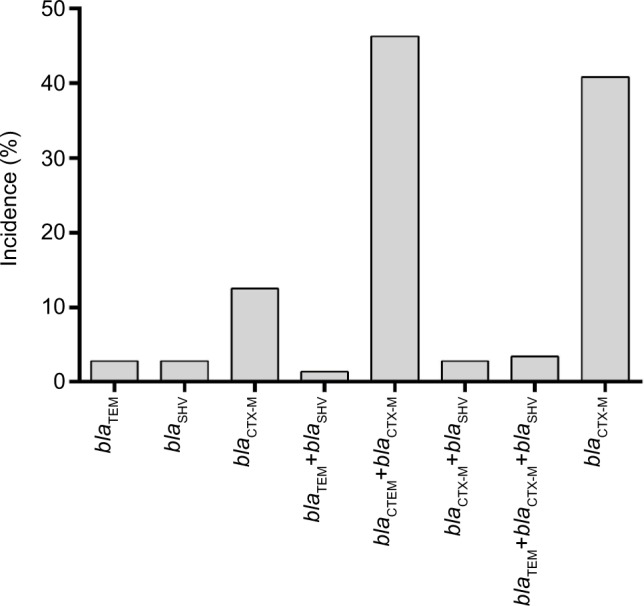

During the study period, 324 cases of EC-caused BSI in hospitalized cancer patients were identified, among which 160 episodes showed positive results and 164 episodes showed negative results in the ESBL confirmation test. In PCR detection of ESBL genotypes, 91.88% of the screened ESBL-positive EC isolates were found to possess one or more of the ESBL genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M) tested in this study (Figure S1). The overall prevalence of ESBL genotypes in EC isolates is shown in Figure 1, and the main genotypes that predominated in these isolates were blaCTX-M-15 (31.29%) and blaTEM-52 plus blaCTX-M-15 (42.17%) (Table S3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of ESBL genotypes in screened positive EC isolates.

Abbreviations: EC, Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

The clinical characteristics of cancer patients with EC-caused BSI are summarized in Table 1. EC-caused BSI occurred in 305 (94.14%) patients with solid tumors, among which most episodes were frequently acquired in patients with pancreatic cancer (61, 20.00%), hepatic carcinoma (49, 16.07%), followed by colorectal cancer (45, 14.75%), gastric carcinoma (43, 14.10%), and gynecological cancer (33, 10.82%). ESBL-EC-caused BSI was associated with recent exposure to antibiotics (cephalosporins and carbapenems), chemotherapy, and BF as determined by univariate analysis. Cancer patients with non-ESBL-EC-caused BSI had received more β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations therapy compared to the ESBL-EC-caused BSI group. After applying a logistic regression model, independent risk factors for infection with ESBL-EC were therapy with third-generation cephalosporin (OR 0.30; 95% CI: 0.09–0.94; P=0.04), chemotherapy (OR 1.80; 95% CI: 1.12–2.89; P=0.02), and BF (OR: 2.79, 95% CI: 1.61–4.83; P<0.001). BF-producing EC-caused BSI was significantly observed in colorectal cancers and hematological malignancies (Table S4). To further determine the risk factors for BF, logistic regression analysis was again used in the regrouped data, and only the ESBL characteristic (OR 3.21; 95% CI: 1.86–5.53; P<0.001) was shown as an independent risk factor for the BF phenotype (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristic of cancer patients with ESBL/non-ESBL EC-caused BSI

| Characteristics | ESBL (n=160), n (%) | Non-ESBL (n=164), n (%) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Males, n (%) | 74 (46.25) | 82 (50.00) | 0.50 | ||

| Age (years), median (range) | 61 (28–83) | 62 (19–85) | 0.26 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 52 (32.50) | 60 (36.59) | 0.27 | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 23 (14.38) | 29 (17.68) | 0.34 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (14.38) | 26 (15.85) | 0.71 | ||

| Underlying disease | |||||

| Solid tumor | 149 (93.13) | 156 (95.12) | 0.44 | ||

| Hematological disease | 11 (6.88) | 8 (4.88) | |||

| Source of BSI | |||||

| Abdominal infection | 35 (21.88) | 41 (25.00) | 0.43 | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 36 (22.50) | 32 (19.51) | 0.60 | ||

| Biliary infection | 47 (29.38) | 47 (28.66) | 0.89 | ||

| Pulmonary infection | 26 (16.25) | 30 (18.29) | 0.73 | ||

| Catheter-related | 8 (5.00) | 3 (1.83) | 0.12 | ||

| Unknown origin | 4 (2.50) | 9 (5.49) | 0.26 | ||

| Othersb | 4 (2.50) | 2 (1.22) | 0.39 | ||

| Previous exposure to antibiotics (within 1 month) | |||||

| Cephalosporin | 34 (21.25) | 20 (12.20) | 0.03 | 0.30 (0.09–0.94) | 0.04 |

| β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor | 17 (10.63) | 36 (21.95) | 0.01 | 0.98 (0.31–3.13) | 0.98 |

| Carbapenem | 95 (59.38) | 79 (48.17) | 0.04 | 0.43 (0.15–1.21) | 0.11 |

| Combined | 8 (5.00) | 16 (9.76) | 0.06 | ||

| Aminoglycosides | 6 (3.75) | 13 (7.93) | 0.11 | ||

| LOS to the first positive culture | 30.89±24.65 | 29.18±19.27 | 0.49 | ||

| Invasive procedure | 81 (50.63) | 79 (48.17) | 0.66 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 106 (66.25) | 84 (51.22) | 0.01 | 1.80 (1.12–2.89) | 0.02 |

| Surgery (within 1 month) | 79 (49.38) | 94 (57.32) | 0.15 | ||

| BF | 57 (35.63) | 24 (14.63) | <0.001 | 2.79 (1.61–4.83) | <0.001 |

Notes:

Multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Intracranial infection; vagina infection; pelvic cavity infection.

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; BSI, bloodstream infection; EC, Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; LOS, length of hospital stay (days).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristic of cancer patients with BF/non-BF EC-caused BSI

| Characteristics | BF-EC (n=81), n (%) | Non-BF-EC (n=243), n (%) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Males, n (%) | 31 (38.27) | 125 (51.44) | 0.04 | 0.59 (0.35–1.01) | 0.05 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 61 (34–84) | 63 (19–85) | 0.38 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 28 (34.57) | 84 (34.57) | 1.00 | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 13 (16.05) | 39 (16.05) | 1.00 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (9.88) | 41 (16.87) | 0.13 | ||

| Underlying disease | |||||

| Solid tumor | 74 (91.36) | 231 (95.06) | 0.22 | ||

| Hematological disease | 7 (8.64) | 12 (4.94) | 0.22 | ||

| Source of BSI | 0.53 | ||||

| Abdominal infection | 17 (20.99) | 59 (24.28) | 0.50 | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 18 (22.22) | 50 (20.58) | 0.81 | ||

| Biliary infection | 23 (28.40) | 71 (29.22) | 0.89 | ||

| Pulmonary infection | 19 (23.46) | 37 (15.23) | 0.09 | ||

| Catheter-related | 1 (1.23) | 10 (4.12) | 0.22 | ||

| Unknown origin | 3 (3.70) | 10 (4.11) | 0.50 | ||

| Others | 1 (1.23) | 5 (2.05) | 0.64 | ||

| Previous exposure to antibiotics (within 1 month) | 0.85 | ||||

| Third-generation cephalosporins | 16 (19.75) | 38 (15.64) | 0.39 | ||

| β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor | 9 (11.11) | 44 (18.11) | 0.14 | ||

| Carbapenems | 48 (59.26) | 126 (51.85) | 0.25 | ||

| Combined | 5 (6.17) | 19 (7.82) | 0.62 | ||

| Aminoglycosides | 3 (3.70) | 16 (6.58) | 0.34 | ||

| Invasive procedure | 39 (48.15) | 121 (49.79) | 0.80 | ||

| Surgery (within 1 month) | 44 (54.32) | 129 (53.09) | 0.90 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 54 (66.67) | 136 (55.97) | 0.09 | ||

| ESBL | 57 (70.37) | 103 (42.39) | <0.001 | 3.21 (1.86–5.53) | <0.001 |

Note:

Multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; BSI, bloodstream infection; EC, Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

Outcome difference among cancer patients with EC-caused BSI

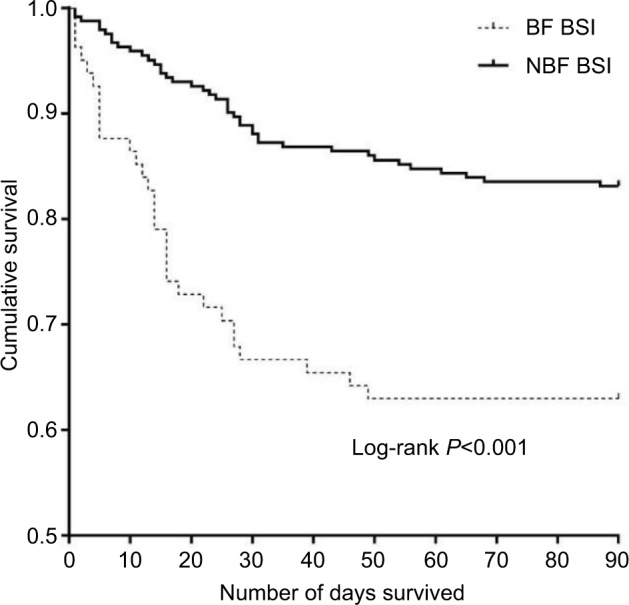

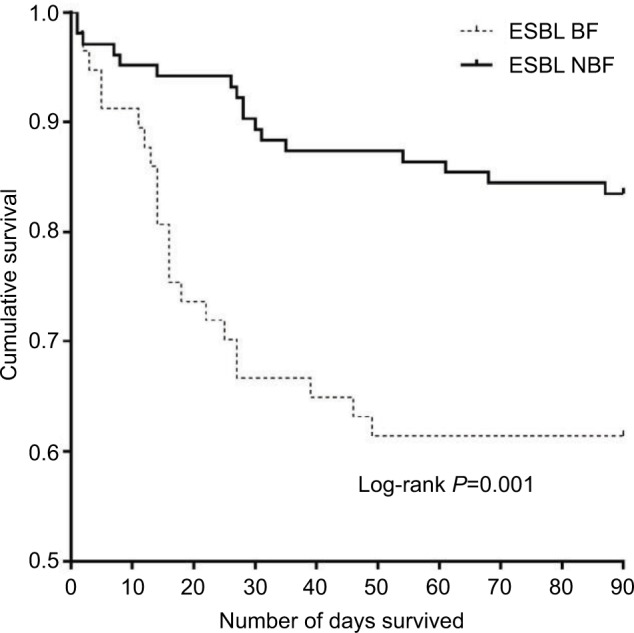

The mortality rate was 21.91% (71/324) for all cancer patients with EC-caused BSI. The overall mortality was significantly higher in the BF-positive EC-caused BSI group compared to that in the BF-negative EC-caused BSI group (42.25% vs 20.16%; log-rank P<0.001) (Figure 2). Compared with the BF-negative ESBL-EC-caused BSI group, the overall mortality was significantly higher in the BF-positive ESBL-EC-caused BSI group (P=0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Survival analysis of EC-caused BSI in cancer patients with/without BF.

Notes: The Kaplan–Meier curve shows the survival curves until day 90 for the two infection groups. The mortality risk was higher among the cancer patients with BF-positive EC-caused BSIs compared with those with BF-negative EC-caused BSIs (P<0.001).

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; BSI, bloodstream infection; EC, Escherichia coli; NBF BSI, BF-negative EC-caused bloodstream infections.

Figure 3.

Survival analysis of ESBL-EC-caused BSI in cancer patients with/without BF.

Notes: The Kaplan–Meier curve shows the survival curves until day 90 for the two infection groups. The mortality risk was higher among the cancer patients with BF-positive ESBL-EC-caused BSIs compared with those with BF-negative EC-caused BSIs (P=0.001).

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; EC, Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

Risk factor analysis between the survival and non-survival cancer patients is summarized in Table 3. Univariate analysis results revealed that diabetes mellitus, LOS, ICU admission, metastasis, mechanical ventilation, BF, organ failure, and the presence of septic shock were significantly associated with death. After multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed, the variables that constituted independent predictors for mortality were metastasis (OR =2.71 95% CI: 1.59–4.63; P=0.001), ICU admission (OR =2.08, 95% CI: 1.13–3.84; P=0.02), BF (OR =2.20, 95% CI: 1.33–3.63; P=0.002), organ failure (OR =10.33, 95% CI: 5.92–18.03; P<0.001), and the presence of septic shock (OR =2.17, 95% CI: 1.24–3.78; P=0.006).

Table 3.

Risk factors associated with the mortality of cancer patients with EC-caused BSI

| Characteristics | Survivors (n=253) | Non-survivors (n=71) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years), median (range) | 63 (19–85) | 61 (34–80) | 0.235 | ||

| Males (n %) | 128 (50.59) | 28 (39.44) | 0.112 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 92 (36.36) | 20 (28.17) | 0.192 | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 42 (16.60) | 10 (14.08) | 0.558 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (12.65) | 17 (23.94) | 0.020 | 1.21 (0.67–2.17) | 0.53 |

| Underlying disease | |||||

| Solid tumor | 240 (94.86) | 65 (91.55) | 0.231 | ||

| Hematological disease | 13 (5.14) | 6 (8.45) | |||

| LOS | 29.05±21.69 | 34.70±23.45 | 0.048 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.96 |

| ICU admission | 19 (7.51) | 15 (21.13) | 0.002 | 2.08 (1.13–3.84) | 0.02 |

| Invasive procedure | 122 (48.22) | 38 (53.52) | 0.494 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 56 (22.13) | 42 (59.16) | <0.001 | 1.27 (0.44–3.63) | 0.66 |

| Metastasis | 100 (39.53) | 46 (64.79) | <0.001 | 2.71 (1.59–4.63) | 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 147 (58.10) | 43 (60.56) | 0.712 | ||

| Surgery | 134 (52.96) | 39 (54.93) | 0.833 | ||

| Previous blood transfusion | 98 (38.74) | 31 (43.66) | 0.520 | ||

| ESBL | 121 (47.83) | 39 (54.93) | 0.310 | ||

| BF | 51 (20.16) | 30 (42.25) | <0.001 | 2.20 (1.33–3.63) | 0.002 |

| Organ failure | 12 (4.74) | 47 (66.20) | <0.001 | 10.33 (5.92–18.03) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis shock | 17 (6.72) | 29 (40.85) | <0.001 | 2.17 (1.24–3.78) | 0.006 |

Note:

Multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; BSI, bloodstream infection; EC, Escherichia coli; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of hospital stay (days).

Discussion

In this study, we retrospectively collected the clinical microbiological characteristic of cancer patients with EC-caused BSI. We systematically evaluated the risk factors, survival difference, and mortality predictors for cancer patients with bloodstream-infected by EC with/without BF. The results showed that prior exposure to cephalosporins, chemotherapy, and BF were three independent risk factors for ESBL-EC-caused BSI. Cancer patients infected by BF-positive ESBL-EC had a lower survival rate. Metastasis, ICU admission, organ failure, septic shock, and BF-positive ESBL-EC infection were five independent risk factors for mortality. These data highlight that BF is closely associated with ESBL-EC-caused BSI and prominently affects the survival of BSI cancer patients.

EC is one of the most frequent causes of BSI in many tertiary care hospitals. Our previous studies revealed that cancer patients often suffer from treatment problems due to EC-caused BSI.17,18 In the present study, we further showed the high prevalence of MDR EC (49.38%) in cancer patients with BSI. PCR amplification based on gene-specific primers followed by nucleotide sequencing provides the easiest and most reliable method to detect the ESBL genotype.15,19,20 Previous studies reported a high prevalence of ESBL-EC in the Asia-Pacific area.15,19,21 Although the CTX-M type of ESBL is believed to be the dominant type in Europe and Asia,15,19,22,23 it was remarkable that in the present study, only 40.82% of ESBL-EC carried the blaCTX-M genotype whereas 46.26% of ESBL-EC carried the blaTEM plus blaCTX-M genotype (Figure 1; Table S3). This result was similar to several clinical observation conducted in other patients,24–27 showing that TEMs genotype are frequently encountered in clinical isolates expressing the CTX-Ms genotype. The reason for co-occurrence of TEM and CTX-M genotypes in ESBL-EC is not clear. It may reflect the redistribution of resistant genes in immunocompromised cancer patients, or provide complementary contributions to the overall resistance of the ESBL producers.28 In addition, it was found that among the isolated ESBL-ECs, 49.38% carried two or three bla genes, which might also account for the high-level β-lactam-resistant phenotype.

BF is a unique mechanism exhibited by several microbes in order to survive in unfavorable conditions. It is a structured community of bacterial cells enclosed in a polymeric matrix and adherent to a surface.9 Biofilm-producing bacteria are highly resistant to antibiotic treatment. The ability of bacterial BF to adhere to medical devices and the use of invasive medical devices are widely recognized.29 It was reported that the prevalence of MDR in BF isolates are more common in comparison to non-BF isolates.3 We found that 81 (25.00%) EC isolates from 324 BSI cancer patients were biofilm producers. To our knowledge, this is the first report of BF in cancer patients with EC-caused BSI. Interestingly, it was found that BF was significantly higher in ESBL-positive EC isolates than in that of ESBL-negative isolates (Table 1). This finding is similar to the investigations on other infectious types. The studies by Subramanian et al and Neupane et al reported similar observations in patients with urinary tract infections that ESBL-EC strains more frequently formed biofilm in comparison to that of non-ESBL-EC isolates.30,31 The reason of the higher ability of ESBL-EC strains to form biofilm is not clear. Activation of several stress response genes and expression of certain virulence genes during bacterial chromosomal gene rearrangements to acquire the ESBL plasmids may be the underlying mechanism.30–33 Among these studies, enhanced biofilm formation capacity in ESBL-plasmid-carrying ST131 and ST648 strains that synthesize virulent- and survival-associated extracellular matrix components (eg, curli fimbriae and/or cellulose) was particularly notable. A deeper understanding of the contribution of transcription factor csgD to biofilm formation and motility capacity in pandemic ESBL-producing EC lineages may be the solution.33

Although BF has been repeatedly described to increase the antibiotic resistance of microorganisms, one study showed it was not associated with any clinical characteristic in patients with EC bacteremia.34 Our study found that BF was not only significantly associated with ESBL-EC-caused BSI but was also an independent risk factor for mortality in BSI cancer patients (Table 3). This finding highlights the equal importance of the BF contribution to mortality as the traditional factors, such as ICU admission, metastasis, organ failure, and shock. Our finding that BF was an independent predictor for mortality further confirms this point. These results are in line with a previous study on enterobacteriaceae-caused infections in non-cancer patients.33 The higher ability of the ESBL-EC to form biofilm increases the mortality and infection severity of cancer patients, making current treatments even more difficult. Therefore, adoption of alternative antibiotics (eg, rifampicin, gentamicin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, tigecycline, colistin, and daptomycin) that can disrupt or inhibit BF may be a good choice.32 Clinicians should take into account the use and doses of BF-response antibiotics to be on the safe side, as exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of these antibiotics can enhance BF. In addition, innovative approaches aimed at overcoming biofilm resistance to conventional antimicrobial agents should be tested in small-scale clinical trials. These include the use of weak organic acids (acetic acid used in hepatology/oncology and citric acid used in hematology/oncology/renal), photo irradiation (blue light therapy), and the application of bacteriophages (phage endolysin with anti-Gram-negative activity).24 Perhaps, combining aspects of these approaches can greatly benefit cancer patients with BF-positive ESBL-EC infection.

Limitations

This study was performed based on a heterogeneous cancer patients group in a single institution, which may present different clinical characteristics than other types of patients and may not reflect the epidemiology of other cancer centres in China. In addition, it is a pity that detailed typing of the ESBL genes was not done.

Conclusion

This study showed that BF is not only significantly associated with the ESBL production by EC but is also an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized cancer patients with BSI. Our findings suggest that the combination of BF-positive ESBL-EC isolates with other appropriate laboratory indicators might benefit infection control and improve clinical outcomes, which may facilitate current antibiotic treatment and prognosis to BSI cancer patients.

Supplementary materials

Multiplex PCR analysis of ESBL-EC isolates.

Notes: PCR products from partial samples were separated in a 1% agarose gel. M, DNA ladder. P, positive control. Previously confirmed EC isolates containing blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes. N, negative control (ddH2O). Lanes 1–6 in (A–C), clinical EC isolates. The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the right, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the left.

Abbreviation: ESBL-EC, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli.

Table S1.

PCR primers used for amplification of ESBL-related genes

| Target gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | Forward Reverse | AAAATTCTTGAAGACG TTACCAATGCTTAATCA | 1,080 |

| blaSHV | Forward Reverse | GGGTTATTCTTATTTGTCGCT TAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG | 929 |

| blaCTX-M | Forward Reverse | TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA CGATATCGTTGGTGGTGCCATA | 544 |

Abbreviation: ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

Table S2.

BF detection values by crystal violet staining

| Strains | OD590 value | Strains | OD590 value | Strains | OD590 value | Strains | OD590 value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 0.352±0.025 | 82 | 0.258±0.107 | 163 | 0.175±0.028 | 244 | 0.613±0.059 |

| 2 | 0.140±0.039 | 83 | 0.162±0.044 | 164 | 0.200±0.015 | 245 | 0.213±0.026 |

| 3 | 0.412±0.092 | 84 | 0.099±0.014 | 165 | 0.142±0.057 | 246 | 0.140±0.052 |

| 4 | 0.153±0.056 | 85 | 0.118±0.033 | 166 | 0.154±0.043 | 247 | 0.276±0.057 |

| 5 | 0.135±0.066 | 86 | 0.220±0.088 | 167 | 0.124±0.028 | 248 | 0.172±0.038 |

| 6 | 0.149±0.08 | 87 | 0.159±0.030 | 168 | 0.178±0.025 | 249 | 0.271±0.047 |

| 7 | 0.211±0.096 | 88 | 0.100±0.019 | 169 | 0.155±0.048 | 250 | 0.175±0.026 |

| 8 | 0.156±0.054 | 89 | 0.432±0.065 | 170 | 0.170±0.033 | 251 | 0.170±0.039 |

| 9 | 0.401±0.067 | 90 | 0.137±0.078 | 171 | 0.139±0.052 | 252 | 0.179±0.025 |

| 10 | 0.150±0.052 | 91 | 0.172±0.037 | 172 | 0.165±0.026 | 253 | 0.376±0.052 |

| 11 | 0.275±0.05 | 92 | 0.129±0.052 | 173 | 0.188±0.029 | 254 | 0.120±0.033 |

| 12 | 0.271±0.102 | 93 | 0.130±0.079 | 174 | 0.195±0.009 | 255 | 0.136±0.057 |

| 13 | 0.234±0.049 | 94 | 0.168±0.039 | 175 | 0.275±0.053 | 256 | 0.166±0.049 |

| 14 | 0.364±0.059 | 95 | 0.128±0.089 | 176 | 0.184±0.007 | 257 | 0.325±0.057 |

| 15 | 0.148±0.064 | 96 | 0.172±0.038 | 177 | 0.166±0.031 | 258 | 0.127±0.051 |

| 16 | 0.155±0.06 | 97 | 0.150±0.039 | 178 | 0.156±0.056 | 259 | 0.152±0.046 |

| 17 | 0.146±0.039 | 98 | 0.137±0.056 | 179 | 0.154±0.024 | 260 | 0.184±0.031 |

| 18 | 0.155±0.062 | 99 | 0.123±0.054 | 180 | 0.168±0.022 | 261 | 0.149±0.034 |

| 19 | 0.128±0.039 | 100 | 0.156±0.061 | 181 | 0.586±0.038 | 262 | 0.354±0.047 |

| 20 | 0.146±0.057 | 101 | 0.110±0.038 | 182 | 0.185±0.014 | 263 | 0.371±0.053 |

| 21 | 0.154±0.058 | 102 | 0.144±0.054 | 183 | 0.141±0.021 | 264 | 0.137±0.051 |

| 22 | 0.481±0.054 | 103 | 0.167±0.045 | 184 | 0.169±0.022 | 265 | 0.145±0.037 |

| 23 | 0.565±0.073 | 104 | 0.322±0.051 | 185 | 0.197±0.014 | 266 | 0.164±0.028 |

| 24 | 0.538±0.091 | 105 | 0.173±0.044 | 186 | 0.126±0.078 | 267 | 0.486±0.044 |

| 25 | 0.152±0.037 | 106 | 0.286±0.091 | 187 | 0.179±0.038 | 268 | 0.581±0.062 |

| 26 | 0.125±0.043 | 107 | 0.140±0.071 | 188 | 0.419±0.042 | 269 | 0.206±0.011 |

| 27 | 0.145±0.042 | 108 | 0.128±0.059 | 189 | 0.152±0.049 | 270 | 0.185±0.012 |

| 28 | 0.150±0.057 | 109 | 0.118±0.049 | 190 | 0.173±0.023 | 271 | 0.168±0.034 |

| 29 | 0.340±0.048 | 110 | 0.169±0.046 | 191 | 0.154±0.057 | 272 | 0.118±0.033 |

| 30 | 0.135±0.058 | 111 | 0.159±0.058 | 192 | 0.140±0.067 | 273 | 0.179±0.038 |

| 31 | 0.158±0.045 | 112 | 0.262±0.099 | 193 | 0.195±0.013 | 274 | 0.191±0.015 |

| 32 | 0.241±0.058 | 113 | 0.161±0.034 | 194 | 0.181±0.027 | 275 | 0.138±0.068 |

| 33 | 0.270±0.068 | 114 | 0.149±0.067 | 195 | 0.169±0.044 | 276 | 0.294±0.042 |

| 34 | 0.271±0.048 | 115 | 0.169±0.039 | 196 | 0.496±0.070 | 277 | 0.271±0.060 |

| 35 | 0.142±0.064 | 116 | 0.152±0.057 | 197 | 0.252±0.114 | 278 | 0.179±0.037 |

| 36 | 0.290±0.069 | 117 | 0.155±0.030 | 198 | 0.246±0.066 | 279 | 0.183±0.029 |

| 37 | 0.152±0.05 | 118 | 0.331±0.043 | 199 | 0.137±0.03 | 280 | 0.189±0.014 |

| 38 | 0.481±0.054 | 119 | 0.167±0.044 | 200 | 0.178±0.038 | 281 | 0.123±0.039 |

| 39 | 0.158±0.037 | 120 | 0.139±0.051 | 201 | 0.341±0.055 | 282 | 0.330±0.060 |

| 40 | 0.149±0.049 | 121 | 0.150±0.055 | 202 | 0.160±0.046 | 283 | 0.399±0.058 |

| 41 | 0.231±0.040 | 122 | 0.162±0.051 | 203 | 0.139±0.059 | 284 | 0.111±0.017 |

| 42 | 0.295±0.074 | 123 | 0.139±0.047 | 204 | 0.188±0.028 | 285 | 0.417±0.086 |

| 43 | 0.335±0.074 | 124 | 0.490±0.050 | 205 | 0.171±0.029 | 286 | 0.275±0.077 |

| 44 | 0.212±0.058 | 125 | 0.165±0.042 | 206 | 0.151±0.055 | 287 | 0.194±0.016 |

| 45 | 0.133±0.064 | 126 | 0.138±0.070 | 207 | 0.184±0.027 | 288 | 0.163±0.054 |

| 46 | 0.149±0.051 | 127 | 0.196±0.011 | 208 | 0.150±0.037 | 289 | 0.253±0.053 |

| 47 | 0.422±0.107 | 128 | 0.628±0.064 | 209 | 0.140±0.074 | 290 | 0.129±0.047 |

| 48 | 0.147±0.043 | 129 | 0.116±0.063 | 210 | 0.529±0.045 | 291 | 0.191±0.025 |

| 49 | 0.305±0.079 | 130 | 0.173±0.044 | 211 | 0.169±0.038 | 292 | 0.156±0.052 |

| 50 | 0.111±0.018 | 131 | 0.162±0.032 | 212 | 0.149±0.062 | 293 | 0.198±0.014 |

| 51 | 0.157±0.047 | 132 | 0.581±0.075 | 213 | 0.144±0.055 | 294 | 0.816±0.043 |

| 52 | 0.214±0.052 | 133 | 0.153±0.044 | 214 | 0.143±0.052 | 295 | 0.266±0.042 |

| 53 | 0.364±0.060 | 134 | 0.189±0.019 | 215 | 0.132±0.082 | 296 | 0.090±0.013 |

| 54 | 0.197±0.072 | 135 | 0.157±0.05 | 216 | 0.161±0.046 | 297 | 0.142±0.040 |

| 55 | 0.145±0.064 | 136 | 0.187±0.015 | 217 | 0.189±0.025 | 298 | 0.130±0.029 |

| 56 | 0.174±0.034 | 137 | 0.185±0.028 | 218 | 0.292±0.052 | 299 | 0.151±0.043 |

| 57 | 0.237±0.088 | 138 | 0.182±0.013 | 219 | 0.369±0.045 | 300 | 0.146±0.040 |

| 58 | 0.171±0.037 | 139 | 0.173±0.038 | 220 | 0.193±0.016 | 301 | 0.128±0.059 |

| 59 | 0.282±0.087 | 140 | 0.206±0.007 | 221 | 0.139±0.055 | 302 | 0.103±0.023 |

| 60 | 0.533±0.108 | 141 | 0.159±0.042 | 222 | 0.178±0.037 | 303 | 0.167±0.024 |

| 61 | 0.129±0.012 | 142 | 0.196±0.017 | 223 | 0.183±0.027 | 304 | 0.198±0.017 |

| 62 | 0.161±0.055 | 143 | 0.129±0.034 | 224 | 0.154±0.042 | 305 | 0.125±0.015 |

| 63 | 0.260±0.080 | 144 | 0.167±0.041 | 225 | 0.171±0.037 | 306 | 0.179±0.037 |

| 64 | 0.146±0.059 | 145 | 0.150±0.058 | 226 | 0.138±0.047 | 307 | 0.259±0.030 |

| 65 | 0.475±0.059 | 146 | 0.396±0.027 | 227 | 0.117±0.042 | 308 | 0.183±0.032 |

| 66 | 0.150±0.056 | 147 | 0.181±0.015 | 228 | 0.174±0.042 | 309 | 0.162±0.029 |

| 67 | 0.371±0.099 | 148 | 0.174±0.022 | 229 | 0.167±0.026 | 310 | 0.325±0.049 |

| 68 | 0.171±0.027 | 149 | 0.205±0.009 | 230 | 0.248±0.029 | 311 | 0.173±0.019 |

| 69 | 0.134±0.072 | 150 | 0.115±0.052 | 231 | 0.156±0.037 | 312 | 0.138±0.064 |

| 70 | 0.144±0.063 | 151 | 0.142±0.041 | 232 | 0.142±0.038 | 313 | 0.203±0.013 |

| 71 | 0.150±0.048 | 152 | 0.150±0.039 | 233 | 0.184±0.027 | 314 | 0.134±0.048 |

| 72 | 0.150±0.054 | 153 | 0.104±0.041 | 234 | 0.189±0.026 | 315 | 0.175±0.041 |

| 73 | 0.127±0.034 | 154 | 0.073±0.022 | 235 | 0.123±0.061 | 316 | 0.169±0.044 |

| 74 | 0.129±0.058 | 155 | 0.290±0.054 | 236 | 0.333±0.064 | 317 | 0.128±0.063 |

| 75 | 0.156±0.054 | 156 | 0.225±0.065 | 237 | 0.110±0.024 | 318 | 0.151±0.048 |

| 76 | 0.556±0.070 | 157 | 0.159±0.038 | 238 | 0.197±0.041 | 319 | 0.595±0.088 |

| 77 | 0.157±0.052 | 158 | 0.173±0.039 | 239 | 0.166±0.038 | 320 | 0.170±0.035 |

| 78 | 0.133±0.071 | 159 | 0.168±0.037 | 240 | 0.174±0.042 | 321 | 0.162±0.043 |

| 79 | 0.155±0.046 | 160 | 0.147±0.045 | 241 | 0.140±0.060 | 322 | 0.200±0.017 |

| 80 | 0.142±0.064 | 161 | 0.169±0.033 | 242 | 0.164±0.043 | 323 | 0.146±0.040 |

| 81 | 0.124±0.063 | 162 | 0.162±0.036 | 243 | 0.180±0.004 | 324 | 0.132±0.033 |

Abbreviation: BF, biofilm formation.

Table S3.

Molecular characterization of bla genes in ESBL-EC isolates

| Genotype of the bla gene | No. of isolates |

|---|---|

|

| |

| TEM-52 | 4 |

| SHV-11 | 2 |

| SHV-12 | 2 |

| CTX-M-1 | 1 |

| CTX-M-14 | 8 |

| CTX-M-15 | 46 |

| CTX-M-28 | 2 |

| CTX-M-19 | 2 |

| CTX-M-27 | 1 |

| TEM-3, SHV-12 | 2 |

| TEM-52, CTX-M-14 | 6 |

| TEM-52, CTX-M-15 | 62 |

| SHV-12, CTX-M-15 | 4 |

| SHV-12, TEM-52, CTX-M-15 | 5 |

Abbreviation: ESBL-EC, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli.

Table S4.

Distribution of BF/non-BF EC-caused BSI in cancer patients

| Tumor type | BF-EC (81) | non-BF-EC (243) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Hematological malignancies | 9 (11.11) | 10 (4.12) | 0.020 |

| Lung cancer | 5 (6.17) | 21 (8.64) | 0.479 |

| Mammary cancer | 9 (11.1) | 16 (6.58) | 0.187 |

| Gynecological cancera | 6 (7.41) | 27 (11.11) | 0.341 |

| Colorectal cancer | 17 (20.99) | 28 (11.52) | 0.033 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 10 (12.35) | 51(20.99) | 0.085 |

| Hepatic carcinoma | 14 (17.28) | 35 (14.40) | 0.532 |

| Gastric carcinoma | 8 (9.88) | 35 (14.40) | 0.299 |

| Bladder cancer | 3 (3.70) | 7 (2.88) | 0.711 |

| Prostate cancer | 0 | 6 (2.47) | 0.154 |

| Renal carcinoma | 0 | 2 (2.1) | 0.413 |

| Othersb | 0 | 5 (2.06) | 0.194 |

Notes:

Includes cervical cancer, endometrial carcinoma, ovarian cancer.

Includes melanoma, buccal cancer, glioma, meningioma.

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; BSI, bloodstream infection; EC, Escherichia coli.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their colleagues who assisted in data collection. Thanks to Dr Edward C Mignot, Shandong University, for linguistic advice. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30700829, No. 81373318), the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (No. 16JCYBJC23900), and the Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. 2016KYZQ03).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. Mortality and delay in effective therapy associated with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae bacteraemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(5):913–920. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tajbakhsh E, Ahmadi P, Abedpour-Dehkordi E, Arbab-Soleimani N, Khamesipour F. Biofilm formation, antimicrobial susceptibility, serogroups and virulence genes of uropathogenic E. coli isolated from clinical samples in Iran. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:11. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costerton B. Microbial ecology comes of age and joins the general ecology community. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(49):16983–16984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407886101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fux CA, Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittal S, Sharma M, Chaudhary U. Biofilm and multidrug resistance in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Pathog Glob Health. 2015;109(1):26–29. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tascini C, Sozio E, Corte L, et al. The role of biofilm forming on mortality in patients with candidemia: a study derived from real world data. Infect Dis (Lond) 2018;50(3):214–219. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2017.1384956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S, Konstantinov SR, Smits R, Peppelenbosch MP. Bacterial biofilms in colorectal cancer initiation and progression. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(1):18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajendran R, Sherry L, Nile CJ, et al. Biofilm formation is a risk factor for mortality in patients with Candida albicans bloodstream infection – Scotland, 2012-2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bereket W, Hemalatha K, Getenet B, et al. Update on bacterial nosocomial infections. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(8):1039–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute CaLS . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Supplement. Twenty-Second Informational Supplement. M100-S22. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma J, Sharma M, Ray P. Detection of TEM & SHV genes in Escherichia coli & Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in a tertiary care hospital from India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:332–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Kim JY, Lee SK, Jin W, Kang SG, Lee KJ. Discriminatory detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases by restriction fragment length dimorphism-polymerase chain reaction. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;31(4):307–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2000.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelstein M, Pimkin M, Palagin I, Edelstein I, Stratchounski L. Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Russian hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(12):3724–3732. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3724-3732.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stepanovic S, Vukovic D, Dakic I, Savic B, Svabic-Vlahovic M. A modified microtiterplate test for quantification of staphylococcal biofilm formation. J Microbiol Methods. 2000;40(2):175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Zhang W, Li Z, et al. Bacteraemia due to AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in hospitalized cancer patients: risk factors, antibiotic therapy, and outcomes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;88(3):247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Li D, Bai C, et al. Clinical prognostic factors for time to positivity in cancer patients with bloodstream infections. Infection. 2016;44(5):583–588. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0890-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiratisin P, Apisarnthanarak A, Laesripa C, Saifon P. Molecular characterization and epidemiology of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates causing health care-associated infection in Thailand, where the CTX-M family is endemic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(8):2818–2824. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00171-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehlers MM, Veldsman C, Makgotlho EP, Dove MG, Hoosen AA, Kock MM. Detection of blaSHV, blaTEM and blaCTX-M antibiotic resistance genes in randomly selected bacterial pathogens from the Steve Biko academic hospital. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;56(3):191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirakata Y, Matsuda J, Miyazaki Y, et al. Regional variation in the prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing clinical isolates in the Asia-Pacific region (SENTRY 1998-2002) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;52(4):323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livermore DM, Canton R, Gniadkowski M, et al. CTX-M: changing the face of ESBLs in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(2):165–174. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feizabadi MM, Delfani S, Raji N, et al. Distribution of bla(TEM), bla(SHV), bla(CTX-M) genes among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae at Labbafinejad Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2010;16(1):49–53. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang H, Ataker F, Hedin G, Dornbusch K. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among Escherichia coli isolates collected in a Swedish hospital and its associated health care facilities from 2001 to 2006. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(2):707–712. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01943-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arpin C, Quentin C, Grobost F, et al. Nationwide survey of extended-spectrum {beta}-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the French community setting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(6):1205–1214. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulvey MR, Bryce E, Boyd D, et al. Ambler class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. in Canadian hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(4):1204–1214. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1204-1214.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero ED, Padilla TP, Hernández AH, et al. Prevalence of clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. producing multiple extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59(4):433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salverda ML, De Visser JA, Barlow M. Natural evolution of TEM-1 β-lactamase: experimental reconstruction and clinical relevance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34(6):1015–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donelli G, Vuotto C. Biofilm-based infections in long-term care facilities. Future Microbiol. 2014;9(2):175–188. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neupane S, Pant ND, Khatiwada S, Chaudhary R, Banjara MR. Correlation between biofilm formation and resistance toward different commonly used antibiotics along with extended spectrum beta lactamase production in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from the patients suspected of urinary tract infections visiting Shree Birendra Hospital, Chhauni, Kathmandu, Nepal. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:5. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian P, Umadevi S, Kumar S, Stephen S. Determination of correlation between biofilm and extended spectrum β lactamases producers of Enterobacteriaceae. Scho Res J. 2012;2(1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jolivet-Gougeon A, Bonnaure-Mallet M. Biofilms as a mechanism of bacterial resistance. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2014;11:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaufler K, Semmler T, Pickard DJ, et al. Carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-plasmids does not reduce fitness but enhances virulence in some strains of pandemic E. coli lineages. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:336. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martínez JA, Soto S, Fabrega A, et al. Relationship of phylogenetic background, biofilm production, and time to detection of growth in blood culture vials with clinical variables and prognosis associated with Escherichia coli bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(4):1468–1474. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1468-1474.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multiplex PCR analysis of ESBL-EC isolates.

Notes: PCR products from partial samples were separated in a 1% agarose gel. M, DNA ladder. P, positive control. Previously confirmed EC isolates containing blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes. N, negative control (ddH2O). Lanes 1–6 in (A–C), clinical EC isolates. The amplified product from each PCR is indicated on the right, and the size of the marker in base pairs is shown on the left.

Abbreviation: ESBL-EC, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli.

Table S1.

PCR primers used for amplification of ESBL-related genes

| Target gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaTEM | Forward Reverse | AAAATTCTTGAAGACG TTACCAATGCTTAATCA | 1,080 |

| blaSHV | Forward Reverse | GGGTTATTCTTATTTGTCGCT TAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG | 929 |

| blaCTX-M | Forward Reverse | TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA CGATATCGTTGGTGGTGCCATA | 544 |

Abbreviation: ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

Table S2.

BF detection values by crystal violet staining

| Strains | OD590 value | Strains | OD590 value | Strains | OD590 value | Strains | OD590 value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 0.352±0.025 | 82 | 0.258±0.107 | 163 | 0.175±0.028 | 244 | 0.613±0.059 |

| 2 | 0.140±0.039 | 83 | 0.162±0.044 | 164 | 0.200±0.015 | 245 | 0.213±0.026 |

| 3 | 0.412±0.092 | 84 | 0.099±0.014 | 165 | 0.142±0.057 | 246 | 0.140±0.052 |

| 4 | 0.153±0.056 | 85 | 0.118±0.033 | 166 | 0.154±0.043 | 247 | 0.276±0.057 |

| 5 | 0.135±0.066 | 86 | 0.220±0.088 | 167 | 0.124±0.028 | 248 | 0.172±0.038 |

| 6 | 0.149±0.08 | 87 | 0.159±0.030 | 168 | 0.178±0.025 | 249 | 0.271±0.047 |

| 7 | 0.211±0.096 | 88 | 0.100±0.019 | 169 | 0.155±0.048 | 250 | 0.175±0.026 |

| 8 | 0.156±0.054 | 89 | 0.432±0.065 | 170 | 0.170±0.033 | 251 | 0.170±0.039 |

| 9 | 0.401±0.067 | 90 | 0.137±0.078 | 171 | 0.139±0.052 | 252 | 0.179±0.025 |

| 10 | 0.150±0.052 | 91 | 0.172±0.037 | 172 | 0.165±0.026 | 253 | 0.376±0.052 |

| 11 | 0.275±0.05 | 92 | 0.129±0.052 | 173 | 0.188±0.029 | 254 | 0.120±0.033 |

| 12 | 0.271±0.102 | 93 | 0.130±0.079 | 174 | 0.195±0.009 | 255 | 0.136±0.057 |

| 13 | 0.234±0.049 | 94 | 0.168±0.039 | 175 | 0.275±0.053 | 256 | 0.166±0.049 |

| 14 | 0.364±0.059 | 95 | 0.128±0.089 | 176 | 0.184±0.007 | 257 | 0.325±0.057 |

| 15 | 0.148±0.064 | 96 | 0.172±0.038 | 177 | 0.166±0.031 | 258 | 0.127±0.051 |

| 16 | 0.155±0.06 | 97 | 0.150±0.039 | 178 | 0.156±0.056 | 259 | 0.152±0.046 |

| 17 | 0.146±0.039 | 98 | 0.137±0.056 | 179 | 0.154±0.024 | 260 | 0.184±0.031 |

| 18 | 0.155±0.062 | 99 | 0.123±0.054 | 180 | 0.168±0.022 | 261 | 0.149±0.034 |

| 19 | 0.128±0.039 | 100 | 0.156±0.061 | 181 | 0.586±0.038 | 262 | 0.354±0.047 |

| 20 | 0.146±0.057 | 101 | 0.110±0.038 | 182 | 0.185±0.014 | 263 | 0.371±0.053 |

| 21 | 0.154±0.058 | 102 | 0.144±0.054 | 183 | 0.141±0.021 | 264 | 0.137±0.051 |

| 22 | 0.481±0.054 | 103 | 0.167±0.045 | 184 | 0.169±0.022 | 265 | 0.145±0.037 |

| 23 | 0.565±0.073 | 104 | 0.322±0.051 | 185 | 0.197±0.014 | 266 | 0.164±0.028 |

| 24 | 0.538±0.091 | 105 | 0.173±0.044 | 186 | 0.126±0.078 | 267 | 0.486±0.044 |

| 25 | 0.152±0.037 | 106 | 0.286±0.091 | 187 | 0.179±0.038 | 268 | 0.581±0.062 |

| 26 | 0.125±0.043 | 107 | 0.140±0.071 | 188 | 0.419±0.042 | 269 | 0.206±0.011 |

| 27 | 0.145±0.042 | 108 | 0.128±0.059 | 189 | 0.152±0.049 | 270 | 0.185±0.012 |

| 28 | 0.150±0.057 | 109 | 0.118±0.049 | 190 | 0.173±0.023 | 271 | 0.168±0.034 |

| 29 | 0.340±0.048 | 110 | 0.169±0.046 | 191 | 0.154±0.057 | 272 | 0.118±0.033 |

| 30 | 0.135±0.058 | 111 | 0.159±0.058 | 192 | 0.140±0.067 | 273 | 0.179±0.038 |

| 31 | 0.158±0.045 | 112 | 0.262±0.099 | 193 | 0.195±0.013 | 274 | 0.191±0.015 |

| 32 | 0.241±0.058 | 113 | 0.161±0.034 | 194 | 0.181±0.027 | 275 | 0.138±0.068 |

| 33 | 0.270±0.068 | 114 | 0.149±0.067 | 195 | 0.169±0.044 | 276 | 0.294±0.042 |

| 34 | 0.271±0.048 | 115 | 0.169±0.039 | 196 | 0.496±0.070 | 277 | 0.271±0.060 |

| 35 | 0.142±0.064 | 116 | 0.152±0.057 | 197 | 0.252±0.114 | 278 | 0.179±0.037 |

| 36 | 0.290±0.069 | 117 | 0.155±0.030 | 198 | 0.246±0.066 | 279 | 0.183±0.029 |

| 37 | 0.152±0.05 | 118 | 0.331±0.043 | 199 | 0.137±0.03 | 280 | 0.189±0.014 |

| 38 | 0.481±0.054 | 119 | 0.167±0.044 | 200 | 0.178±0.038 | 281 | 0.123±0.039 |

| 39 | 0.158±0.037 | 120 | 0.139±0.051 | 201 | 0.341±0.055 | 282 | 0.330±0.060 |

| 40 | 0.149±0.049 | 121 | 0.150±0.055 | 202 | 0.160±0.046 | 283 | 0.399±0.058 |

| 41 | 0.231±0.040 | 122 | 0.162±0.051 | 203 | 0.139±0.059 | 284 | 0.111±0.017 |

| 42 | 0.295±0.074 | 123 | 0.139±0.047 | 204 | 0.188±0.028 | 285 | 0.417±0.086 |

| 43 | 0.335±0.074 | 124 | 0.490±0.050 | 205 | 0.171±0.029 | 286 | 0.275±0.077 |

| 44 | 0.212±0.058 | 125 | 0.165±0.042 | 206 | 0.151±0.055 | 287 | 0.194±0.016 |

| 45 | 0.133±0.064 | 126 | 0.138±0.070 | 207 | 0.184±0.027 | 288 | 0.163±0.054 |

| 46 | 0.149±0.051 | 127 | 0.196±0.011 | 208 | 0.150±0.037 | 289 | 0.253±0.053 |

| 47 | 0.422±0.107 | 128 | 0.628±0.064 | 209 | 0.140±0.074 | 290 | 0.129±0.047 |

| 48 | 0.147±0.043 | 129 | 0.116±0.063 | 210 | 0.529±0.045 | 291 | 0.191±0.025 |

| 49 | 0.305±0.079 | 130 | 0.173±0.044 | 211 | 0.169±0.038 | 292 | 0.156±0.052 |

| 50 | 0.111±0.018 | 131 | 0.162±0.032 | 212 | 0.149±0.062 | 293 | 0.198±0.014 |

| 51 | 0.157±0.047 | 132 | 0.581±0.075 | 213 | 0.144±0.055 | 294 | 0.816±0.043 |

| 52 | 0.214±0.052 | 133 | 0.153±0.044 | 214 | 0.143±0.052 | 295 | 0.266±0.042 |

| 53 | 0.364±0.060 | 134 | 0.189±0.019 | 215 | 0.132±0.082 | 296 | 0.090±0.013 |

| 54 | 0.197±0.072 | 135 | 0.157±0.05 | 216 | 0.161±0.046 | 297 | 0.142±0.040 |

| 55 | 0.145±0.064 | 136 | 0.187±0.015 | 217 | 0.189±0.025 | 298 | 0.130±0.029 |

| 56 | 0.174±0.034 | 137 | 0.185±0.028 | 218 | 0.292±0.052 | 299 | 0.151±0.043 |

| 57 | 0.237±0.088 | 138 | 0.182±0.013 | 219 | 0.369±0.045 | 300 | 0.146±0.040 |

| 58 | 0.171±0.037 | 139 | 0.173±0.038 | 220 | 0.193±0.016 | 301 | 0.128±0.059 |

| 59 | 0.282±0.087 | 140 | 0.206±0.007 | 221 | 0.139±0.055 | 302 | 0.103±0.023 |

| 60 | 0.533±0.108 | 141 | 0.159±0.042 | 222 | 0.178±0.037 | 303 | 0.167±0.024 |

| 61 | 0.129±0.012 | 142 | 0.196±0.017 | 223 | 0.183±0.027 | 304 | 0.198±0.017 |

| 62 | 0.161±0.055 | 143 | 0.129±0.034 | 224 | 0.154±0.042 | 305 | 0.125±0.015 |

| 63 | 0.260±0.080 | 144 | 0.167±0.041 | 225 | 0.171±0.037 | 306 | 0.179±0.037 |

| 64 | 0.146±0.059 | 145 | 0.150±0.058 | 226 | 0.138±0.047 | 307 | 0.259±0.030 |

| 65 | 0.475±0.059 | 146 | 0.396±0.027 | 227 | 0.117±0.042 | 308 | 0.183±0.032 |

| 66 | 0.150±0.056 | 147 | 0.181±0.015 | 228 | 0.174±0.042 | 309 | 0.162±0.029 |

| 67 | 0.371±0.099 | 148 | 0.174±0.022 | 229 | 0.167±0.026 | 310 | 0.325±0.049 |

| 68 | 0.171±0.027 | 149 | 0.205±0.009 | 230 | 0.248±0.029 | 311 | 0.173±0.019 |

| 69 | 0.134±0.072 | 150 | 0.115±0.052 | 231 | 0.156±0.037 | 312 | 0.138±0.064 |

| 70 | 0.144±0.063 | 151 | 0.142±0.041 | 232 | 0.142±0.038 | 313 | 0.203±0.013 |

| 71 | 0.150±0.048 | 152 | 0.150±0.039 | 233 | 0.184±0.027 | 314 | 0.134±0.048 |

| 72 | 0.150±0.054 | 153 | 0.104±0.041 | 234 | 0.189±0.026 | 315 | 0.175±0.041 |

| 73 | 0.127±0.034 | 154 | 0.073±0.022 | 235 | 0.123±0.061 | 316 | 0.169±0.044 |

| 74 | 0.129±0.058 | 155 | 0.290±0.054 | 236 | 0.333±0.064 | 317 | 0.128±0.063 |

| 75 | 0.156±0.054 | 156 | 0.225±0.065 | 237 | 0.110±0.024 | 318 | 0.151±0.048 |

| 76 | 0.556±0.070 | 157 | 0.159±0.038 | 238 | 0.197±0.041 | 319 | 0.595±0.088 |

| 77 | 0.157±0.052 | 158 | 0.173±0.039 | 239 | 0.166±0.038 | 320 | 0.170±0.035 |

| 78 | 0.133±0.071 | 159 | 0.168±0.037 | 240 | 0.174±0.042 | 321 | 0.162±0.043 |

| 79 | 0.155±0.046 | 160 | 0.147±0.045 | 241 | 0.140±0.060 | 322 | 0.200±0.017 |

| 80 | 0.142±0.064 | 161 | 0.169±0.033 | 242 | 0.164±0.043 | 323 | 0.146±0.040 |

| 81 | 0.124±0.063 | 162 | 0.162±0.036 | 243 | 0.180±0.004 | 324 | 0.132±0.033 |

Abbreviation: BF, biofilm formation.

Table S3.

Molecular characterization of bla genes in ESBL-EC isolates

| Genotype of the bla gene | No. of isolates |

|---|---|

|

| |

| TEM-52 | 4 |

| SHV-11 | 2 |

| SHV-12 | 2 |

| CTX-M-1 | 1 |

| CTX-M-14 | 8 |

| CTX-M-15 | 46 |

| CTX-M-28 | 2 |

| CTX-M-19 | 2 |

| CTX-M-27 | 1 |

| TEM-3, SHV-12 | 2 |

| TEM-52, CTX-M-14 | 6 |

| TEM-52, CTX-M-15 | 62 |

| SHV-12, CTX-M-15 | 4 |

| SHV-12, TEM-52, CTX-M-15 | 5 |

Abbreviation: ESBL-EC, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli.

Table S4.

Distribution of BF/non-BF EC-caused BSI in cancer patients

| Tumor type | BF-EC (81) | non-BF-EC (243) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Hematological malignancies | 9 (11.11) | 10 (4.12) | 0.020 |

| Lung cancer | 5 (6.17) | 21 (8.64) | 0.479 |

| Mammary cancer | 9 (11.1) | 16 (6.58) | 0.187 |

| Gynecological cancera | 6 (7.41) | 27 (11.11) | 0.341 |

| Colorectal cancer | 17 (20.99) | 28 (11.52) | 0.033 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 10 (12.35) | 51(20.99) | 0.085 |

| Hepatic carcinoma | 14 (17.28) | 35 (14.40) | 0.532 |

| Gastric carcinoma | 8 (9.88) | 35 (14.40) | 0.299 |

| Bladder cancer | 3 (3.70) | 7 (2.88) | 0.711 |

| Prostate cancer | 0 | 6 (2.47) | 0.154 |

| Renal carcinoma | 0 | 2 (2.1) | 0.413 |

| Othersb | 0 | 5 (2.06) | 0.194 |

Notes:

Includes cervical cancer, endometrial carcinoma, ovarian cancer.

Includes melanoma, buccal cancer, glioma, meningioma.

Abbreviations: BF, biofilm formation; BSI, bloodstream infection; EC, Escherichia coli.