Abstract

Theory of change (ToC) is currently the approach for the evaluation and planning of international development programs. This approach is considered especially suitable for complex interventions. We question this assumption and argue that ToC’s focus on cause–effect logic and intended outcomes does not do justice to the recursive nature of complex interventions such as advocacy. Supported by our work as evaluators, and specifically our case study of an advocacy program on child rights, we illustrate how advocacy evolves through recursive interactions, with outcomes that are emergent rather than predictable. We propose putting “practices of change” at the center by emphasizing human interactions, using the analytical lenses of strategies as practice and recursiveness. This provides room for emergent outcomes and implies a different use of ToC. In this article, we make a clear distinction between theoretical reality models and the real world of practices.

Keywords: theory of change, practices of change, practice theory, advocacy, advocacy evaluation, recursiveness, emergent outcomes, strategy as practice

In international development, theory of change (ToC) is a widely used and discussed method for planning and evaluation. This method aims to address linkages between objectives, strategies, outcomes, and assumptions that support an intervention’s mission and vision. It began as a theory of how and why an intervention works, exploring underlying assumptions about change processes and beliefs about how an intervention contributes to these changes (Weiss, 1997, 2000). In the context of analyzing how complex interventions plan for and achieve outcomes, ToC is used to acquire funding (Valters, 2014, p. 1). It is thus a management tool that is used as a formal planning document or as a broader approach to analyze how development processes work. ToC is referred to as a “road map” or “blueprint” for getting from “here to there” (Stachowiak, 2013, p. 2; Stein & Valters, 2012, p. 3). Increasingly, ToC has become a new paradigm, touted as an ideal tool for planning and evaluating effectiveness that does justice to the complexity of development interventions (Barnes, Matka, & Sullivan, 2003; Reisman, Gienapp, & Stachowiak, 2007; Vogel, 2012).

We distinguish two applications of ToC: ex ante, as an approach to strategy development and planning, and ex post, as a monitoring and evaluation approach. In our evaluation of eight transnational advocacy programs (2012–2015), we used ToC to reconstruct how change was understood, pursued, and achieved (Arensman et al., 2015). By focusing on the practices of advocacy in a case study of a Pan-African child rights advocacy program, this article looks at ToC primarily as an approach to monitoring and evaluation. From our evaluation, we learned that ToC, in its current form, does not do justice to the dynamic nature of advocacy practices. We asked whether the (ex post) use of ToC could be improved to do more justice to the complex nature of advocacy, which is shown as emergent and recursive by our case study findings. In this article, we propose a refinement of the use of ToC, introducing practices of change in addition to theory of change.

Advocacy is an increasingly important strategy for sustainable development effectiveness. We define advocacy for international development interventions as “a wide range of activities conducted to influence decision makers at different levels toward the overall aim of development interventions to combat the structural causes of poverty and injustice” (Arensman et al., 2015, p. 42; following Morariu & Brennan, 2009, p. 100). Advocacy comprises a variety of substrategies and activities, including campaigning, awareness raising, creating critical mass, lobbying, and cooperating with targets you seek to influence. Thus, advocacy is often multilevel, with differentiated linkages across levels; multisited, with differentiated linkages across sites; and multiactor, with differentiated engagements, understandings, and roles in program and involving multiple organizational structures, capacities, and accountability relations. Although some authors claim that ToC is specifically useful for such complex processes (Beer & Reed, 2009; Jones, 2011), others have already questioned whether ToC in its current state lives up to this potential (Jabeen, 2016; Mowles, 2013).

The logic of ToC produces predefined, intended outcomes and does not sufficiently problematize the complex nature of development processes. Critics have questioned whether ToC is the right tool to deal with complex development interventions such as advocacy (Mason & Barnes, 2007; Valters, 2014). The presentation of a ToC is often a requirement for donor funding, showing the planning for implementation and for evaluating effectiveness. Some have questioned whether ToC is just the next “trick” to perform in the name of accountability (Valters, 2014; van Es & Guijt, 2015). Others have stressed that there is a risk of ToC being imposed by the results agenda, which emphasizes assessing effectiveness using predefined and intended outcomes for accountability (Eyben, Guijt, Roche, & Schutt, 2015; Riddell, 2014). This raises several questions: What does this mean for the ToC approach in monitoring and evaluating advocacy interventions? Can the use of ToC be improved to mitigate the problem of unpredictability?

Based on our findings, we argue that practices of change should be emphasized in addition to ToC. This argument is inspired by a study conducted by Teles and Schmitt (2011) who proposed evaluating advocacy by looking at the advocates rather than the outcomes. However, they did not translate this ambition into a practical approach. In response to their argument and addressing the need they identified, we bring practice-based theory, developed in management and evaluation studies, together with our case study findings. We propose using Jarzabkowski’s (2005) analytical lens of strategy as practice (SAP) to give expression to practices. Using this lens provides important insight into how practices have evolved, as compared with theory. It considers strategy as something actors do in interaction and in reaction to the organizational and contextual environments rather than what organizations have as a fixed set of skills. Strategies are thus dynamic practices rather than static assets. This implies the social construction of strategies, as actors have agency over their decisions (see Long, 2003). Emphasizing strategy as the product of human action and interaction makes it possible to do justice to the complex nature of advocacy. Hence, we argue that the use of ToC as an evaluation approach can be enriched by “practices of change.”

This article proceeds by highlighting the challenges of ToC as an evaluation approach. We then discuss how to look at ToC differently by introducing the discussions in management studies on SAP and recursiveness. We then introduce our case study, discussing the approach and methods used therein. Next, we present our analysis of the child rights advocacy program to illustrate the emergent nature that advocacy outcomes have in practice. Based on these findings, we introduce a new use for ToC, taking a practices of change approach to advocacy evaluation. We conclude by summarizing our findings and linking them to macro discussions in the development field and propose suggestions for future research.

ToC and Advocacy Evaluation

In international development, many planning and evaluation tools are used to gain control over program effectiveness. ToC evolved from the linear logic model, the log frame. The log frame only lists inputs and outputs, without looking at the different elements in relation to each other. In its monitoring agenda, it focuses on intended outcomes, which is problematic for processes where not everything can be planned. Additionally, the log frame does not allow for insight into the processes leading to outcomes or space to incorporate influences from the changing context (Prinsen & Nijhof, 2015). ToC was meant to resolve these problems.

ToC was developed from program theory in the tradition of theory-based evaluation and is concerned with how and why an intervention works (Weiss, 1997, 2000). Program theory studies the interrelation between the mechanisms of change, the program, and the outcomes it intends to achieve. A growing number of studies claim ToC is the best approach for dealing with complex social and political change processes because it emphasizes the links between objectives, strategies, outcomes, and assumptions (Beer & Reed, 2009; Louie & Guthrie, 2007; Stein & Valters, 2012; Vogel, 2012). There is no universally agreed understanding of the exact nature of ToC, although it is often referred to as a road map, theory for action, or blueprint for strategic planning and learning (Reisman et al., 2007). Despite ToC being celebrated and widely used, studies have shown that tensions exist between its ambitions and its implementation, demonstrating that the approach is not yet living up to these ambitions (Eyben et al., 2015; Mowles, 2013; Valters, 2014).

For this reason, ToC has been criticized as both a planning and monitoring and evaluation tool. Mowles (2013, pp. 47–49) found that ToC is predominantly used as an outcome-based approach that evokes cause–effect thinking (i.e., if we do this, then this will be the result). Consequently, this emphasizes the intended outcomes foreseen by policy-relevant theories and plans (Coryn, Noakes, Westine, & Schröter, 2011; Valters, 2014). Moreover, ToC as a monitoring and evaluation approach has triggered highly critical voices questioning whether it is the best approach for complex interventions or rather a new donor-driven results tool.

ToC follows a cause–effect and if–then logic that tends to focus on how the program expects to achieve its intended outcomes (Vogel, 2012). Therefore, it does not pay attention to other outcomes, such as those that are not anticipated or intended.1 Van Es and Guijt (2015) illustrated how ToC as an approach, both ex ante and ex post, is limited by the political pressure focusing on intended results, which does not enable a reflective and learning environment. Valters (2014) argued along the same lines, adding that, in the ToC approach, the institutional environments (i.e., bureaucracies, funding agreements, and program planning) and limited resources (i.e., time and funding) mean that accountability trumps learning. Eyben (2015, p. 21) conceived of ToC as results artifact, helping to achieve the politically desired outcomes that must be accounted for. This reality contradicts the ambition of ToC to be a reflective and critical approach. Thus, ToC as an evaluation approach becomes a framework for testing predefined hypotheses as was also confirmed by Bamberger, Tarsilla, and Hesse-Biber (2016).

Barnes, Matka, and Sullivan (2003) stressed that the evaluation of nonlinear processes involving multiple stakeholders and relations demands multiple theories of change. They argued that the contested interpretations of stakeholders, who all have different interests and demands, need to be addressed. Building on this, we consider advocacy a complex intervention because it pursues multilevel change, works in multistakeholder settings, crosses borders, and concerns diverse levels of policy arenas. Rogers’s (2008, p. 39) work helps with the understanding of the outcomes of advocacy interventions as emergent rather than intended or planned. She considers outcomes to emerge through interactions during the process of implementation. Emergent outcomes, including unintended outcomes, can be mistaken for ineffective management, although these outcomes actually point to evolving, strategic and flexible approaches as well as complex processes. If evaluators focus merely on intended outcomes, these emergent outcomes are easily overlooked.

At the same time, multiple advocacy researchers have claimed that ToC is essential and strategically important for understanding the changes advocacy achieves (Jones, 2011; Klugman, 2011; Stachowiak, 2013). In our case study, the program did not articulate a ToC specifically but was assessed on its outcomes using the ToC method. We reconstructed a ToC for that purpose. We noticed serious tensions between the cause–effect logic in the reconstructed ToC approach and the observed practices of doing advocacy (i.e., adapting to changing circumstances, communications, and interactions), including recursive strategizing resulting in emergent outcomes. These tensions included the focus on intended outcomes, with other outcomes remaining concealed. There was no explanation in the ToC for how these unintended outcomes came about. Seeking to do more justice to the dynamic advocacy processes, we therefore suggest twinning theoretical models and theorized relations, as seen in the ToC, with practices of change, which provide space for recursiveness and emergence.

Creating Space for Practices of Change

The idea of ToC adheres to the notion that planned models equal the real world. When plans are made in anticipation of change, there is an implicit understanding that change and the implementation of these plans are driven by policies. This can be overcome by emphasizing and articulating practices in addition to theorizing how change evolves. Strategy as practice offers an analytical lens that can make a difference in the evaluation of complex advocacy interventions.

Breaking down the existing body of knowledge around ToC, we note that “strategy” is an important element. However, ToC is not suited to the explicit integration of strategy as an evolving practice central to change processes but rather theorizes that if we use this strategy, then this will be the outcome. This emphasizes the intended outcomes and places the theory above changing practice. From public health intervention studies, process evaluation is another approach that pursues a shift from outcome focus to processes (Hulscher, Laurant, & Grol, 2003). However, this approach also underscores the notion that planned theoretical models equal the real world while it focuses on intended processes. It does not provide space for understanding practices as strategies and interactions. Inspired by management studies, we turn this around by focusing on practices in addition to program theorizing. By looking at the processes as they happen in practice, we see strategy as something actors do while adapting to changing circumstances.

SAP is a strand of management studies that was developed from the acknowledgment that organizational processes should be understood from practice. This makes both the theorizing and the practices of strategy meaningful. SAP explains how strategy is dynamic, as it is enabled and constrained by actors, human interactions, and organizational and societal practices (Vaara & Whittington, 2012). Jarzabkowski (2005, p. 7) defined strategy as a situated, socially accomplished flow of activity that has consequential outcomes for the direction and/or survival of an organization. She showed that interactions are always pursued while keeping a future mission in mind. This implies that actors act strategically, with a mission (i.e., agenda, interest) that guides their work. At the same time, they must also deal with the daily dilemmas of reconciling a constantly changing world with the need for stability because this is essential for an organization to function effectively and efficiently (Jarzabkowski, 2004, p. 530). Jarzabkowski and other SAP scholars (e.g., van Wessel, van Buuren, & van Woerkum, 2011) have addressed actions and interactions as dynamic and complex, acknowledging that organizations are not necessarily a coherent whole, but rather fragmented, pluralistic, and contested. SAP therefore provides a shift from performance-based approaches (in the sense of a results agenda) to actual understanding of how strategy evolves. Strategy, then, is a type of activity that is dynamic and shaped by practitioners and practices (i.e., routines, tools, methods, discourses, meetings, communication, and behavior).

Using a SAP lens enables the understanding of practices as they evolve, rather than framing them in line with a predefined theoretical model. This provides space for interaction between the theory and the practices. In other fields that bring together theory and practice, it is considered important to focus on strategies to understand how these are used to address challenges and needs, shape interactions, and influence trust building (see Coburn & Penuel, 2016). Feldman and Orlikowski (2011, p. 1249) have argued that there is a need for the development of a practice theory to enable a focus on empirical and microlevel processes constructed through relations. Relatedly, Langley (2007) has shown that bridging microlevel relations and macro environments requires process thinking. Process thinking considers “how and why things—people, organizations, strategies, environments—change, act and evolve over time” (Langley, 2007, p. 2). SAP provides an analytical lens to gain better insight into such processes by zooming in on the practices.

As our case study will show, addressing “how” and “why” questions in advocacy evaluation requires an understanding of strategies as dynamic practices. Focusing on these practices provides insight on the recursiveness of advocacy. Recursiveness means that each decision, direction, or step results from the previous ones and generates new starting conditions for the rest of the process through interaction, learning, and decision-making (Crozier, 2007). This recursiveness demands the continuous reconsidering, redefining, and restrategizing of advocacy strategies through feedback loops of interactions between stakeholders and organizational/environmental contexts. Through these feedback loops, new starting conditions are developed, based on learning and integrating new ways of thinking, decision-making, and strategizing. Crozier (2007, pp. 10–13) has illustrated this point with political communications, which are interpreted through and influenced by actions and interactions. Communication and knowledge are transformed through feedback loops between the sender and the receiver, depending on how the information is received and interpreted. What happens in these feedback loops is thus largely unforeseen (Crozier, 2007). This also implies that outcomes inherent to a recursive process should be considered emergent. Giving space to strategies as practices enables insight into these loops and the relations between strategizing, interactions, and outcomes.

To date, recursiveness has not been given prominence in advocacy or in studies discussing ToC as planning, monitoring, and evaluation approach. A limited number studies have mentioned recursiveness in relation to international development interventions. These studies have considered recursiveness in the context of nonlinearity, multiple pathways of change, multidimensionality and emergence. Patton (1997, p. 232) discussed recursiveness as an element of multidirectional and multilateral relationships. For advocacy, we argue that these relationships, as practices, are key to the strategies. We therefore consider recursiveness fundamental. Looking at advocacy interventions, Rogers (2008) argued that strategies need to be revisited continuously, as practices to pursue change are recursively generated through feedback loops that create new starting conditions with each output.

Whereas ToC focuses on theorizing change from policies, SAP emphasizes that change is initiated from practices and then should find its way back into policy. Rather than seeing processes as linear or causally linked, SAP provides space for understanding practices as recursive and their outcomes as emergent. In the next sections, we present our case study findings, which demonstrate the importance of focusing on practices to grasp the meaning of outcomes. We show how advocacy outcomes came about through recursive strategies as practices, rather than as planned change processes, as was an initial assumption in our ToC methodology. This justifies using SAP as an analytical lens for understanding the practices of change and illustrates that advocacy outcomes are emergent, not necessarily either intended or unintended.

Method and Case Study

This study was part of a broader research project based on a transnational advocacy evaluation (2012–2015) commissioned by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs in cooperation with the Foundation for Joint Evaluations. The evaluation was administered by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. We were involved as evaluators and researchers. The evaluation assessed eight transnational advocacy programs that were funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and implemented by a variety of Dutch nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in cooperation with partners worldwide. For this article, we drew from one of the eight advocacy program. This program was the advocacy component of a broader child rights program. It was executed by an alliance of Dutch NGOs but implemented solely by an international NGO (INGO) in Ethiopia that focused on Pan-African child rights. The Dutch alliance referred to this INGO as a “strategic” partner.

Our research was a multisited ethnographic study of this Pan-African child rights advocacy program, which we studied through time and space (see Marcus, 1995). We gathered data using diverse methods (see Arensman et al., 2015, for full details). We conducted 147 semistructured interviews and held formal and informal meetings with staff and management, program managers, and the board of the Ethiopia-based INGO. We interviewed the Dutch alliance partners and staff members of targeted organizations, including African policy makers and other African partners. We also analyzed more than 200 documents, including documents internal to the organization and external public and policy documents. We observed five strategic advocacy events in 2012, 2013, and 2014, and we gathered feedback during formal and informal meetings with staff members, individual program managers, and with the organizations’ management. We conducted participant observation and outcome tracing in the Netherlands, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda, Namibia, South Africa, and the United States (New York), but time and space limitations did not allow a survey of the full Pan-African scope of the advocacy program. We were unable to visit Francophone or Maghreb countries or Central or Western African countries. Therefore, the data cannot be generalized or considered representative of the Pan-African scope of the program.

We invested in trust building while remaining independent outsiders to the program. This approach gave us the opportunity to work closely with the advocacy program’s staff, enabling us to improve our understanding by gaining access to privileged information. The longitudinal nature of the evaluation made it possible to monitor how information and stakeholders developed, thus acquiring progressive insight. For confidentiality reasons, the names of interviewees are not given in this article. The next section describes the case in more detail.

The Case Study

The African Child Policy Forum [ACPF] was founded as an organization in 2003 in response to the need to improve the well-being of children in Africa. As children were not able to represent themselves in (political) processes to improve their well-being, ACPF stepped in as the African voice on child rights:

We speak about the ‘African Child’, and not about the ‘Child in Africa’, as our philosophy. We are African with international values. ACPF has international value by default. We anchor our knowledge on different international standards. We have gone international Pan-African, but if we go global international we may lose our legitimate moral voice for African children, losing that specific African flavour. (Program manager, 2012)

The organization was based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, near the African Union (AU). In 2013, the organization had 30 staff members (including support staff) and an independent Board of Trustees with international child rights expertise. Their main mission was presented as follows:

Despite Africa’s progress over the last decade and the impressive achievements to date in improving the lives and wellbeing of children, accelerated and sustained efforts are required in terms of legal reform, investment of resources and policy implementation. (African Report on Child Wellbeing, ACPF, 2013, p. xvi)

ACPF focused its advocacy work on content-driven ways to hold governments accountable in order to improve child rights and child well-being. In the years of the evaluation, they focused on intercountry adoption, government budgets for children, violence against children, government accountability to children and child well-being in African countries, among other issues. In theory, ACPF aimed to pursue its mission by targeting the AU, African governments, and NGOs. The main strategies to bring about change were knowledge building, speaking out against child rights violations, contributing to legal and policy reforms and effective implementation, alliance building of child rights organizations to forge a common voice, and collaboration with the AU and international partners. Staff members expressed a great deal of (personal) dedication to the main goal of their advocacy: improving child well-being. Therefore, “putting children on the agenda” was often emphasized in reports and interviews.

A conventional donor–recipient relation existed between ACPF and its funding partner in the Netherlands. This created power asymmetry, because the partner in the Netherlands provided funding based on a plan of action that was to comply with donor requirements.2 The two organizations acted from different perspectives and interests (multiple realities3) and did not always sufficiently connect with each other.

Case Study Findings

Theory and Practices of Change

In the evaluation methodology, ToC was at center stage. When we arrived in Ethiopia in 2012, we were thus harnessed with concepts including “pathways of change,” “outcomes,” and “outputs” and with tools such as contribution analysis. However, we decided to approach the program with an open mind, enabling reflection on our preliminary findings from our document analysis.

Our preliminary study of documents and interviews with the Dutch alliance in the Netherlands had not surfaced the ToC ACPF was pursuing. The Dutch alliance partner had stressed that ACPF was mainly doing research. What advocacy or outreach was being undertaken in daily practices was not explicitly known. We therefore first tried to reconstruct the ToC and intended outcomes ourselves (a paper exercise), but interviews and documentation provided by ACPF communicated another reality as to how change was pursued and achieved in daily practices. Noting this, we questioned staff members about how they had bridged the multiple realities. Jointly, we tried again to retrieve the ToC in order to evaluate how it had worked out in practice. We understood that the notion of ToC had been introduced to ACPF by the Dutch partner. This was elaborated in a joint ToC workshop that was organized in 2012 with the goal of inspiring improved effectiveness. The staff within ACPF had accepted ToC as a donor-given tool, but they had not explicitly used it in their way of working. The ToC as defined in the workshop was not really an issue of discussion with the Dutch funding agent.

Although ACPF did not have a clearly spelled-out ToC, they did think about and reflect on what they pursued and how they went about this. One of the program managers emphasized this point:

We do not have an overall theoretically written ToC; we have a ToC in practice, because we have internal discussions and you are always asked by the team to account for what you are doing and for the choices made, for example, on the justification of the project or the choices made. […] At our organisational level, we have a strategy document titled From Era of Rhetoric to an Era of Accountability. That gives us an overarching direction. (Program manager, 2012)

The staff members thus implicitly emphasized the practice side of their work over the theory, explaining how they continually and recursively worked and strategized in practice. This meant that their advocacy interventions were experienced as evolving in practice rather than in a structured on a theoretical basis or institutionalized in the organizational way of working.

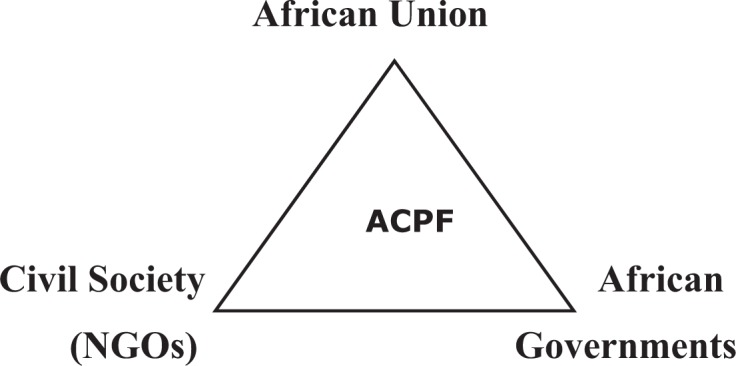

We also found that ACPF was, in theory, predominantly targeting its actions toward the AU, African governments, and NGOs. Figure 1 demonstrates the theory through which they aspired to pursue change. Their reports, strategic documents, and interviews framed this as direct and explicit advocacy toward these three targets. They often stressed how they were influencing governments:

We constantly organise launches, which we see as advocacy events due to our identification of the country-specific issues. In country briefs, we report where a country is lagging. We have different countries to deal with, and we have local partners who take it up. Local and international bodies take it up. (Program manager, 2012)

Figure 1.

African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) theory of change (Arensman et al., 2015).

Note. NGO = nongovernmental organization.

This interview extract illustrates how staff members spoke about their output and facilitative role as self-evidently influencing change. They had not distinguished between the immediate output of their work and the effect it had on their targets (outcome), a point that will be further discussed in the following section. Content-driven advocacy as a strategy was often discussed as a self-explanatory cycle that naturally trickles down to results and influence: “We are about advocacy, because whatever we produce has to have an effect, a result. We advocate for those results” (Program manager, 2012).

In ACPF’s annual monitoring reports, they spoke mainly of program outputs, which they often presented as outcomes. We started to look beyond the output and, together with the staff, reviewed the narratives on what happened in practice to reach their targets and achieve advocacy results (outcomes). In these narratives, we found not only additional outcomes but also strategies other than those that had been outlined in theory. Their advocacy was taking shape in a recursive way in much more strategic and emergent forms.

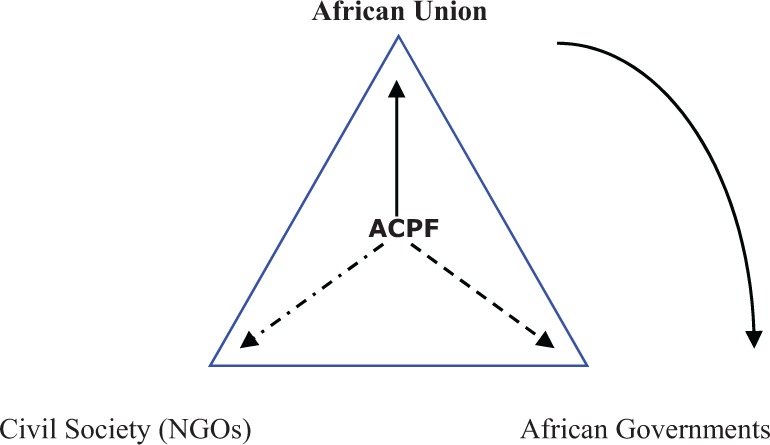

In addition, it appeared that governments were not a direct target for ACPF. Rather, they were targeted through the AU. Further, the country-specific activities were limited. Thus, we concluded that, in reality, ACPF followed another pathway toward change, targeting, and cooperating with different stakeholders (Figure 2). Comparing Figure 2 with Figure 1 demonstrates the difference between the theory (Figure 1) and the practice of change (Figure 2) pursued by the organization. This practice was not reflected in any theoretical model. We found that the organization’s staff members were not fully aware of the influence they wielded. Consequently, many of the outcomes they achieved were not seen, reported or followed up. In other cases, more outcomes could have been achieved if they had realized what they had set into motion with their output. In one of the countries, for example, a workshop was conducted to introduce one of the child rights reports. This workshop was highly appreciated by the participants. However, the report (recommending strengthening child rights) was never translated into the national language, and it was scarcely distributed; thus, its outreach remained limited. The next section discusses how this advocacy work evolved and developed in an emergent way.

Figure 2.

African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) practice of change (Arensman et al., 2015).

Note. NGO = nongovernmental organization.

Intended and Emergent Outcomes

In the first conversation, we had with the Dutch partner organization in 2012, it was stressed that “their [ACPF’s] research work is solid and rigorous, but the question is how they achieve effectiveness” (Evaluation manager, 2012). In other words, the work they were doing was good, but the Dutch partner did not know what the output was or what ACPF was achieving. However, upon arrival in Ethiopia, we received a document from ACPF that included their output and achievements to date. The document was also sent to the donors. It described the many activities, events, and launches organized, as well as the reports written. Still, this document focused strongly on outputs, and it was missing narratives of how changes or outcomes had been achieved and of ACPF’s influence.

Together with the program managers and through country visits, we sought to coconstruct the practices of change—what happened, what action was undertaken, what strategies were implemented, how, and why. Through this coconstruction, a different picture of ACPF’s work and outcomes appeared. What ACPF had reported as achievements were often actually outputs (products of the work of ACPF’s staff), but it turned out to be the case that their work had brought about many more further-reaching changes. This new understanding made it clear that many outcomes were not planned or intended but had emerged beyond ACPF’s direct control or influence. Some outcomes had previously been overlooked or not understood as outcomes to which ACPF had contributed. This was confirmed particularly through interviews during the country visits.

Another overarching pertinent question arose: Why had we not learned about some of these outcomes from the funding partner in the Netherlands? We established that the result reports in the Netherlands were based on ex ante (linear) planning (ToC) for which a monitoring protocol was designed in accordance with the donor’s requirements. This raised the question of whether insufficient space and time for mutual understanding and collective reflection on outcomes between ACPF and the Dutch partner could have been a limiting factor in identifying outcomes. To phrase it differently, had this advocacy program been conceived as a conventional development project (driven by linear theory) rather than a recursive and multidimensional advocacy intervention?

This situation, we found, illustrates the dichotomy between theory, which is formulated around intentions and assumptions, and emergent advocacy practices and their results. To understand practice, we listened to and analyzed verbal and reported narratives. We learned that the challenge with advocacy is understanding outcomes as occurring in practice, rather than approaching outcomes through a ToC that starts from preplanned results and their assessment through preset indicators (see Coffman & Reed, 2009; Teles & Schmitt, 2011).

Recursive Outcome Loops

One of the issues ACPF advocated for was “budgeting for children,” which spiraled into opportunities for exerting influence at diverse levels and layers of governance. In 2011, ACPF researched, prepared, and launched a report on this issue. When we asked staff members about their achievements, they spoke about the process of publishing and launching this report. We then investigated what happened beyond this, questioning whether any changes had occurred. It was reported that the issue was brought to the attention of INGOs, which were already familiar with ACPF because they were present at the report launch in 2011. One of these INGOs kept in contact with ACPF and, in 2013, asked them to cooperate in an international consortium on child rights governance. This provided a new opportunity for ACPF to advance the issue on INGOs’ agendas. The uptake of the issue of budgeting for children in an international consortium generated a broader scope of interest. The consortium’s collective efforts eventually resulted in targeted strategic advocacy actions aiming to influence the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva (UNCRC).4 This, in turn, again provided a new starting point for ACPF, because it introduced the organization to the UN fora. An ACPF staff member explained how ACPF contributed to “the development of a proposal to be submitted to the UNCRC” and how this evolved into a new strategy for ACPF:

Through the Committee and focusing on child rights is the way, we can influence governments. When the Committee puts it in, we have legal pressure to influence. We submitted the proposal and made a presentation in Geneva during one of their sessions. (Program manager, 2014)

Acting on emerging opportunities that provide for new starting conditions is a recursive loop (Crozier, 2007). The ‘loop” can be described as follows: ACPF’s 2011 research report led to the message that budgeting for children is required to protect children’s rights. This was taken up and interpreted as something of significant value, first by the INGO and then by the international consortium and the UNCRC. This uptake became a new starting point for continuing and strengthening the advocacy message, thus expanding its influence even further:

There is a meeting in September in Geneva, where I [a program manager] will be talking, presenting. There is a change in relation to the Africa report and in relation to our ToC. […] We partnered for global advocacy on public spending to realise child rights in line with our 2011 report, and we wanted to take it further. This consortium provided an opportunity at various levels. (Program manager, 2014)

This resulted in a number of new advocacy outcomes: “The big outcome is that the Committee accepted the proposal. It is going further; they have established a working group [WG], and they asked us to provide support to this WG” (Program manager, 2014).

We also found other outcomes emerging from these recursive loops of interactions. A partnership was established around specific child rights issues. Space was created on the agenda of INGOs, and the UNCRC took up the issue of budgeting for children:5

We as [a] working group drafted the work plan, and it became a zero draft for the UN Child Rights Committee, while for us it is a final draft. The Committee looked at it, and it was accepted. And we needed a scoping document on the question—what should the scope of the document be. We are now defining the content and we knew the strategy and impact. Now our work is transferred into a general comment with key elements. And what we think should be there is there. (Program manager, 2014)

From these narratives and reports, it surfaced that the major outcome was the influence generated at UN level for advocating for the African voice for children and the recognition that such an African voice exists. ACPF turned out to have been highly responsive to the opportunities provided:

What has happened [is], once they [the UNCRC] had agreed, we developed a work plan on what they should be doing. We have monthly teleconferences in the consortium. We have been working very hard on it. What happened [is] there was a need to develop the working plan, and we developed it and shared it. (Program manager, 2014)

These outcomes were emerging from interactions between the stakeholders involved. Through these interactions, information flows inspired action, cooperation, and influence. This process stimulated strategizing and restrategizing, which gave meaning to the advocated issues. This situation illustrates how advocacy outcomes come about through recursive practices under often unpredictable and unforeseen circumstances.

Practices of Change

ToC, in its current form, is used with a focus on control and predictability. This focus is at odds with the need and ambition to provide space for understanding how processes develop and evolve in reality. Our case study demonstrates the need to appreciate practices in order to understand effectiveness. Our findings prove that advocacy is recursive and emergent rather than linear and causal. In their strategic decision-making, advocates interact, react, and adapt. When organizations focus on what they intend to achieve (ToC), often in relation to donors’ agendas and accountability demands, they overlook what is actually achieved in practice. We suggest refining the use of existing ToCs to understand change as initiated from practices in which human interactions are central: practices of change. This is not another model; rather, it exposes the theoretical model to the real world of practices.

Theory-based approaches to evaluation such as ToC are valuable because they construct (ex ante) oversight and insight into the envisaged processes of change pursued by a program. Critically questioning assumptions and beliefs encourages program staff to reflect on their roles, missions, agendas, and strategies. Questioning helps to pave the way for examining the human interactions and relations. However, although it is valuable, ToC does not clarify human interactions in everyday practices. We found that the theoretical ideas about change differed from what we identified in practice, and we learned that ToC as an evaluation approach has two interrelated shortcomings. First, although it describes how and why an intervention works in theory, it overlooks practice. This results in the second shortcoming: ToC thus fails to pay attention to outcomes that were not intended. What actually happens in practice (emergent and recursive) can therefore easily be overlooked (see also Jabeen, 2016). To help us evaluate the programs, we felt theory was one thing, but we also needed to understand practices.

The complex and unpredictable nature of advocacy demands that evaluators investigate both theory and practices. This requires a framework that provides room for both. According to Jarzabkowski (2005, p. 172), “a framework is only valuable in relation to the conditions under which it applies.” As our case study shows, change may be strategized in theory, but it actually happens in the interactions between actors, influenced by organizational environments, policy arenas, and social and cultural contexts. This multilevel playing field is shaped by theories, practices, and the interactions between the two. To understand advocacy outcomes as they are, rather than seeking to assess outcomes against a predefined theoretical framework, evaluators must examine how strategy develops in practice.

What does this mean for evaluation practice? Strategy in ToC is one theorized element (if we do this, then this happens), but it becomes central when looking at the practices—not as if–then logic, but rather as how-did-it-evolve logic. SAP foregrounds human interactions and is a way to look at advocacy processes and understand how advocacy strategy develops through daily practices. It is important to explore how such strategy is shaped over time, across multiple levels, stakeholders, borders, and perspectives. Understanding strategy as something actors do rather than something organizations have gives room to practices while also making it possible to relate practice with theory (ToC). This means that it takes human interactions and processes—rather than theoretical, predefined outcomes—as a starting point for understanding effectiveness. For evaluation, looking at the practices of change through the lens of SAP and recursiveness provides a new perspective for understanding the outcomes of complex processes, such as advocacy. This includes looking at outcomes as emergent, beyond intent.

By twinning practices of change and ToC in the way evaluators and organizations work, we believe that change, even if it happens over a long time period—which is often the case in advocacy—can be captured in terms of how it actually evolves. Twinning practices of change and ToC thus provides evaluators and program staff with the space to follow and trace advocates’ progress over time (including small steps, practices changed, strategies adapted, and achievements), reflect on the practices together, and establish plausible connections between these practices and changes (even if these changes occur over a long time period). This approach thus encourages advocates to more openly record their steps as they evolve, develop, and flow in their day to day practices.

In advocacy evaluation, we argue that understanding practices of change demands more than questioning and theorizing processes as a sequence of events that will lead to a desired outcome (Vogel, 2012) or testing and proving the theorized causal hypothesis (Mowles, 2013). This clearly has implications for the role and position of evaluators, who need to look beyond theory to observe, investigate, and explore practices. Doing so will require a shift from cause–effect thinking, which emphasizes outcome planning and reporting, to putting advocates at the center. Advocates act strategically while they make practical judgments, maneuvering through changing circumstances and acting in interaction with contexts (both organizational and environmental) and theory (plans and objectives). These practices need to be understood and reflected upon in terms of strategies, recursiveness, and human interactions. Only then can an evaluator assess the broader scope of a program’s achievements.

Besides establishing common ground, evaluators should take an open, qualitative approach to collecting data. Evaluators should listen well and without prejudice, and they should critically question and investigate the strategic practices. Narratives around strategies as dynamic practices become key in establishing how change processes are shaped and developed; what human interactions are meaningful; and how this relates to diverse roles, perspectives, theories, and achievements. This means that close cooperation with program staff is necessary to create space and build the trust required for transparency (i.e., open discussions, learning, and joint reflection). This demands fostering moral courage to tell an honest story, even addressing those things that failed. To optimize reflection and learning, it is advisable to start evaluation of practices during the implementation.

For evaluation purposes, we consider practices of change a necessary complement to “ToC.” Additionally, practices can be used to mirror theory. This may provide plausible explanations for how outcomes (practice) relate to policy (theory) and its program planning. The tensions between theory and practice are a well-documented field of concern in development practices (see Eyben et al., 2015; Wallace, 2006).

Conclusions

The above discussion demonstrates that ToC is potentially suitable as an approach for planning dynamic advocacy interventions, but we argue that, for evaluation purposes, ToC should be twinned with practices of change. Whereas ToC focuses on theorizing change from policies, the idea of practices of change emphasizes that change is initiated from strategies as practices shaped by human interactions. This approach provides a practical solution to the problem posed by Teles and Schmitt (2011) who argued that current evaluation approaches are limited in terms of evaluating advocacy and suggested evaluating the advocates instead of the outcomes. The kind of twinning we suggest makes the case that theory and practice cannot be separated in evaluation.

Our approach provides the space necessary to elucidate processes that are unpredictable in nature (not predicted in any ToC), encouraging evaluators to look beyond the pursued outcomes. We argue for emphasizing practices as a mirror to theories, challenging the traditions of prediction and control. Understanding the correlation between policy (theory) and outcomes (practice) clearly requires evaluators to explore and analyze connections between theories and practices. Theorizing how change works provides insight into the beliefs, assumptions, and ideas about change, whereas exploring how change is pursued and achieved in practice provides insight into interactions, strategies, and decision-making.

Therefore, we argue that the theory-based approach (ToC) should be twinned with the practice-based approach. The combination of both approaches provides useful insights into the complex processes between policy and implementation that can bridge the gap between the world of theory and the world of practices. This combined approach also provides space to take distance from and reflect on theory while doing justice to practices. New theories can be constructed on the basis of understanding practices. This should then find its way back into practice.

Our case study specifically focused on advocacy evaluation, but our findings may be relevant beyond advocacy to the broader field of working with and evaluating complex interventions that continuously evolve over time. We realize that evaluation and recording (documenting) of Practices of Change in advocacy requires further study and methodology development, acknowledging advocacy as strategic in interactions and as form of practical judgment. There is a wide body of evaluation methodologies available to draw upon also in other sectors, such as the education field. Two of the authors are also involved in developing and designing a methodology specifically for advocacy evaluation that takes a practice approach, looking at advocacy as strategic in interactions and as a form of practical judgment. We encourage more case studies to be done to accompany (advocacy) evaluations enhancing understanding of outcomes. But also to contribute to elaborating a practice theory of evaluating complex interventions such as advocacy. Enhanced understanding and analyses of practices should also contribute to policy improvement.

Acknowledgments

The researchers are grateful for the openness and cooperation of the staff members of the evaluated program and the management team as well as the network members and partners. Special thanks to Dr. Jennifer Barrett for many meaningful suggestions and language editing.

Notes

See also Jabeen (2016) for reflections on the emphasis on intended outcomes in international development discussions.

Further treatment of power relations is beyond the scope of this article. Refer to Wallace (2006), Eyben (2008), and Mosse and Lewis (2005) on this issue. In the case of African Child Policy Forum (ACPF), the alliance partner in the Netherlands had made serious efforts to correct this imbalance, but these were not always successful (see Chapter 12 in Arensman et al., 2015).

This phenomenon and the challenges of multiple realities are discussed by Hilhorst (2003).

See UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 19 (2016) on public budgeting for the realization of children’s rights (Art. 4); The Child Rights Working Group on Investment in Children, UNCRC adopts a general comment on public budgeting for the realization of children’s rights. Retrieved from November 28, 2016, http://www.childrightsconnect.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/WG_on_IC_statement_welcoming_GC_adoption_ENG.pdf

This includes further cooperation with United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) International. See UNICEF Executive Board meeting “Special focus session on Africa,” June 3, 2014, New York, statement by Theophane Nikeyema, executive director of ACPF: Retrieved from November 28, 2016, https://papersmart.unmeetings.org/media2/3346480/acpf-statement-at-unicef-special-focus-session-3-jun-14.pdf

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was part of a PhD research project supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

References

- African Child Policy Forum. (2013). The African report on child wellbeing 2013: Towards greater accountability to Africa’s children. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arensman B., Barrett J. B., van Bodegom A., Hilhorst D., Klaver D., van Waegeningh C., van Wessel M. (2015). MFS II joint evaluation of international lobbying and advocacy. Wageningen, the Netherlands: Wageningen University & Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger M., Tarsilla M., Hesse-Biber S. (2016). Why so many “rigorous” evaluations fail to identify unintended consequences of development programs: How mixed methods can contribute. Evaluation and Program Planning, 55, 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M., Matka E., Sullivan H. (2003). Evidence, understanding and complexity: Evaluation in non-linear systems. Evaluation, 9, 165–284. [Google Scholar]

- Beer T., Reed E. D. (2009). A model for multilevel advocacy evaluation. The Foundation Review, 1, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn C. E., Penuel W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher, 45, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Coffman J., Reed E. D. (2009). Unique methods in advocacy evaluation. Retrieved from http://www.pointk.org/resources/files/Unique_Methods_Brief.pdf

- Coryn C. L., Noakes L. A., Westine C. D., Schröter D. C. (2011). A systematic review of theory-driven evaluation practice from 1990 to 2009. American Journal of Evaluation, 32, 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier M. (2007). Recursive governance: Contemporary political communication and public policy. Political Communication, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Eyben R. (2008). Power, mutual accountability and responsibility in the practice of international aid: A relational approach (Working Paper 305). Brighton, England: Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Eyben R. (2015). Uncovering the politics of evidence and results In Eyben R., Guijt I., Roche C., Schutt C. (Eds.), The politics of evidence and results in international development: Playing the game to change the rules? (pp. 19–38). Rugby, England: Practical Action. [Google Scholar]

- Eyben R., Guijt I., Roche C., Schutt C. (Eds.). (2015). The politics of evidence and results in international development: Playing the game to change the rules? Rugby, England: Practical Action. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M. S., Orlikowski W. J. (2011). Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science, 22, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Hilhorst D. (2003). The real world of NGOs: Discourses, diversity and development. London, England: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hulscher M. E. J. L., Laurant M. G. H., Grol R. P. T. M. (2003). Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 12, 40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen S. (2016). Do we really care about unintended outcomes? An analysis of evaluation theory and practice. Evaluation and Program Planning, 55, 144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarzabkowski P. (2004). Strategy-as-practice: Recursiveness and adaptation, and practices-in-use. Organization Studies, 25, 529–560. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzabkowski P. (2005). Strategy as practice: An activity-based approach. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jones H. (2011). A guide to monitoring and evaluating policy influence (ODI Background note). London, England: Overseas Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Klugman B. (2011). Effective social justice advocacy: A theory-of-change framework for assessing progress. Reproductive Health Matters, 19, 146–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley A. (2007). Process thinking in strategic organization. Strategic Organization, 5, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Long N. (2003). Development sociology: Actor perspectives. London, England: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Louie J., Guthrie K. (2007). Strategies for assessing policy change efforts: A prospective approach. The Evaluation Exchange, 13, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24(1), 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mason P., Barnes M. (2007). Constructing theories of change: Methods and sources. Evaluation, 13, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Morariu J., Brennan K. (2009). Effective advocacy evaluation: The role of funders. The Foundation Review, 1, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mosse D., Lewis D. (Eds.). (2005). The aid effect: Giving and governing in international development. London, England: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mowles C. (2013). Evaluation, complexity, uncertainty: Theories of change and some alternatives In Wallace T., Porter F., Ralph-Bowman M. (Eds.), Aid, NGOs and the realities of women’s lives: A perfect storm (pp. 47–60). Rugby, England: Practical Action. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (1997). Utilization-focused evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Prinsen G., Nijhof S. (2015). Between log frames and theory of change: Reviewing debates and a practical experience. Development in Practice, 25, 234–246. [Google Scholar]

- Reisman J., Gienapp A., Stachowiak S. (2007). A guide to measuring advocacy and policy. Baltimore, MD: Organisational Research Services. [Google Scholar]

- Riddell R. C. (2014, February). Does foreign aid really work? Keynote address at the Australasian Aid and International Development Workshop, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P. (2008). Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions. Evaluation, 14, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak S. (2013). Pathways for change: 10 theories to inform advocacy and policy change efforts. Center for Evaluation Innovation. Seattle, WA: ORS Impact. [Google Scholar]

- Stein D., Valters C. (2012). Understanding theory of change in international development: A review of existing knowledge (JSRP Paper 1). London, England: JSRP and The Asia Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Teles S., Schmitt M. (2011). The elusive craft of evaluating advocacy. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vaara A., Whittington R. (2012). Strategy-as-practice: Taking social practices seriously. The Academy of Management Annals, 6, 285–336. [Google Scholar]

- Valters C. (2014). Theories of change in international development: Communication, learning or accountability? (JSRP Paper 17). London, England: JSRP and The Asia Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- van Es M., Guijt I. (2015). Theory of change as best practice or next trick to perform? Hivos’ journey with strategic reflection In Eyben R., Guijt I., Roche C., Schutt C. (Eds.), The politics of evidence and results in international development: Playing the game to change the rules? (pp. 95–114). Rugby, England: Practical Action. [Google Scholar]

- van Wessel M., van Buuren R., van Woerkum C. (2011). Changing planning by changing practice: How water managers innovate through action. International Public Management Journal, 14, 262–283. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel I. (2012). Review of the use of ‘theory of change’ in international development. London, England: UK Department of International Development. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace T. (Ed.). (2006). The aid chain: Coercion and commitment in development NGOs. Rugby, England: Practical Action. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C. H. (1997). Theory-based evaluation: Past, present and future. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 76, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C. H. (2000). Theory-based evaluation: Theories of change for poverty reduction programs In Feinstein O. N., Picciotto R. (Eds.), Evaluation and poverty reduction (pp. 103–114). Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]