Abstract

Ferroptosis, a new form of regulated cell death that is iron- and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent, has attracted much attention in the research communities of biochemistry, oncology, and especially the material sciences. Since the first demonstration by Stockwell et al. in 2012, a series of strategies have been developed to induce ferroptosis of cancer cells, including the use of nanomaterials, clinical drugs, experimental compounds, and genes. A plethora of research work has outlined the blueprint of ferroptosis as a new option for cancer therapy. However, the published ferroptosis related reviews have mainly focused on the mechanisms and pathways of ferroptosis, which motivated us to contribute a review to bridge the gap between biological significance and material design. Therefore, it is timely to summarize the previous efforts on the emerging strategies for inducing ferroptosis and shed light on future directions for using such a tool to fight against cancer. In this review, we will elaborate on the current strategies of cancer therapy based on ferroptosis, highlight the design considerations and the advantages and limitations, and finally give a future perspective on this emerging field.

Keywords: ferroptosis, Fenton reaction, lipid peroxidation, iron based nanomaterials, cancer therapy

1. Introduction

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death that is iron- and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent. Interestingly, the discovery of ferroptosis long preceded its conception in 2012 by Stockwell.[1] In 2001, a unique form of programmed nerve cell death caused by oxidative stress was found and termed oxytosis.[2] The preliminary research involving this form of cell death provided foundational evidence highly relevant to ferroptosis.[3] Studies conducted with conditional knockout mice for glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) provided early evidence that the loss of GPX4 causes a form of non-apoptotic cell death.[4] In 2003, erastin was found to be cytotoxic to human foreskin fibroblasts engineered to express mutant Ras oncogene (BJeLR), but not their isogenic primary counterparts.[5] In 2008, small molecule Ras-selective lethal compounds, (RSL)-3 and RSL5, were also identified to selectively kill BJeLR cells in a non-apoptotic manner.[6] In addition, inhibition of apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, and autophagy by necrostatin-1 and wortmannin inhibitors could not block the cell death induced by RSLs.[1] On the contrary, antioxidant vitamin E and iron chelator deferoxamine mesylate could inhibit cell death induced by the RSLs.[1] Necrostatin-1 was also shown to inhibit ferroptosis as an off-target effect in GPX4 knockout cells.[7] Although the notion of ferroptosis was not yet proposed then, the above-mentioned cell death was essentially caused by ferroptosis.

Since the term ferroptosis was coined in 2012, numerous studies have proposed the underlying mechanisms of ferroptosis. Thus far, some regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of ferroptosis have been identified. Activation of mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels and mitogen-activated protein kinases, upregulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress, and inhibition of cystine/glutamate antiporter are believed to be involved in ferroptosis.[8] In this process, accumulation of lipid peroxidation products and ROS derived from iron metabolism occurs, which can be pharmacologically inhibited by lipid peroxidation inhibitors (e.g., liproxstatin, ferrostatin, and zileuton) or iron chelators (e.g., desferrioxamine mesylate and deferoxamine).[8] In addition, GPX4,[7,9] heat shock protein beta-1 (HSPB1),[10] and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) function as negative regulators of ferroptosis by limiting ROS production and reducing cellular iron uptake.[8] Previous studies indicate that ferroptosis depends on Ras-ERK signaling and can be completely blocked by MEK inhibition.[11] Subsequently, it was found that this conclusion is inaccurate, likely due to the use of MEK inhibitor U0126 in the previous studies. The U0126 was compared with a more selective and potent MEK1/2 inhibitor, PD0325901. The U0126, but not PD0325901 was found to be able to block cell death induced by either erastin or amino acid starvation in the presence of serum. Therefore, MEK activity is not essential for ferroptosis. The effects of U0126 are mainly based on its antioxidant function.[12] In addition, it also may be due to off-target inhibition of certain unknown enzymes required for ferroptosis. Overall, the most important feature of ferroptosis is iron- and ROS-dependency.[13–16]

In addition, the morphological, biochemical and genetic features of ferroptosis are also quite different from the other types of regulated cell death, such as apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, and autophagy.[8,17] Morphologically, the cells with ferroptosis compared with normal cells have smaller mitochondria, decreased or vanishing mitochondria crista, condensed mitochondrial membrane, and ruptured outer mitochondrial membrane.[8,18–20]

Ferroptosis has attracted increasing attention over the years. Up to now, some regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of ferroptosis have been clarified.[8,21] In a recent review, ferroptotic mechanisms, inducers of ferroptosis, and inhibitors of ferroptosis were introduced.[22] After the ferroptotic mechanisms were clarified and the inducers and inhibitors of ferroptosis were found, most of the current studies of ferroptosis have focused on the discovery of ferroptosis-inducing agents including small molecules, nanomaterials (with or without iron), and genes, which could be developed as cancer therapy strategies.

2. Small Molecules for Ferroptosis-based Cancer Therapy

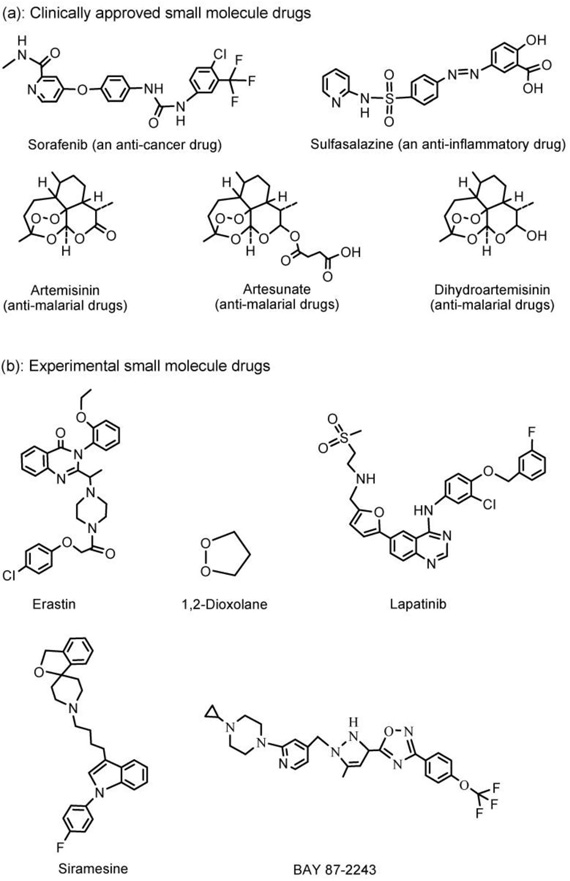

Other than the oncogenic RAS-selective lethal small molecule erastin,[1] several clinical drugs have also been found to be able to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells. As shown in Figure 1, these drugs include: (1) Sorafenib (an anti-cancer drug); (2) Sulfasalazine (an anti-inflammatory drug); and (3) Artemisinin and its derivatives, including Artesunate and Dihydroartemisinin (anti-malarial drugs).

Figure 1.

Structures of the clinically approved (a) and experimental (b) small molecule drugs that are able to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells.

Lachaier et al.[23] identified sorafenib, an inhibitor of oncogenic kinases, as an inducer of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines. This conclusion was drawn based on the observation that the cytotoxic effect of sorafenib on HCC cells was largely prevented by iron chelation by deferoxamine. Subsequently, Louandre et al.[24] and Sun et al.[25] also confirmed that sorafenib can induce ferroptosis.

The anti-inflammatory drug sulfasalazine (Azulfidine in U.S. and Salazopyrin in Europe) was mainly used to treat rheumatic polyarthritis and especially chronic ulcerative colitis. It was also found that sulfasalazine inhibits the glutamate transporter xCT (SCL7a11, system Xc-, SXC) and induces ferroptotic cell death in glioma cells.[26–28]

Antimalarial drug artemisinin and its derivatives can generate ROS and lead to oxidative stress in cancer cells.[29] Eling et al. demonstrated that artesunate specifically induces ROS- and lysosomal iron-dependent cell death in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells.[30] Roh et al. investigated the molecular mechanisms behind the antitumor effects of artesunate in head and neck cancer (HNC).[31] Their study showed that artesunate selectively killed HNC cells by inducing ferroptosis. However, ferroptotic cell death by artesunate may be suboptimal in some cisplatin-resistant HNCs due to the activation of the Nrf2-antioxidant response element (ARE) signaling pathway. Inhibition of the Nrf2-ARE pathway by silencing Keap1 (a negative regulator of Nrf2) increased artesunate sensitivity and reversed the ferroptosis resistance in HNC cells. Lin et al. demonstrated that dihydroartemisinin specifically causes head and neck cancer cell death through contribution from both ferroptosis and apoptosis, and dihydroartemisinin may represent an effective strategy in head and neck cancer treatment.[32]

Besides the clinically approved drugs, many experimental compounds (Figure 1) were found to be able to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells via the regulation of GPX4. For example, Stockwell et al. determined that GPX4 is a central regulator of ferroptosis and that ferroptosis can be induced in mouse tumor xenografts by erastin because erastin depletes glutathione and inactivates GPX4.[33–35] Abrams et al. identified 1,2-dioxolane as a lead compound from screening a library of organic peroxides to induce ferroptosis that warrants further investigation for the potential treatment of cancer.[36] Ma et al. demonstrated that siramesine (a lysosome disrupting agent) and lapatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) induced ferroptosis in breast cancer cells (e.g. MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, ZR-75 and SKBr3) over a 24 h time course.[37] Schockel et al. recently demonstrated that BAY 87–2243, a potent inhibitor of NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase (complex I), induced dose-dependent ferroptosis on a panel of BRafV600E melanoma cell lines.[38,39] Summarily, the experimental compounds including erastin, 1,2-dioxolane, siramesine, lapatinib, and BAY 87–2243 (Figure 1), are promising as potential clinical drugs for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy.

3. Nanomaterials for Ferroptosis-Based Cancer Therapy

The ferroptosis process is characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products and lethal ROS derived from iron metabolism and can be pharmacologically inhibited by iron chelators (e.g., deferoxamine and desferrioxamine mesylate). Therefore, although the precise and complete role of iron in ferroptosis remains unclear, the iron-catalyzed ROS production (i.e., Fenton chemistry) is an important pathway for iron induced ferroptosis.

The oxidation of organic substrates by iron (II or III) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is called Fenton chemistry or Fenton reaction, which was first described by H. J. H. Fenton in 1894.[40,41] The Fenton reaction between iron (II or III) and H2O2 has been widely accepted and is described as follows:[40,41]

| (1) |

| (2) |

Based on the Fenton reaction, various nanomaterials have been developed for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy.

3.1. Iron-Based Nanomaterials

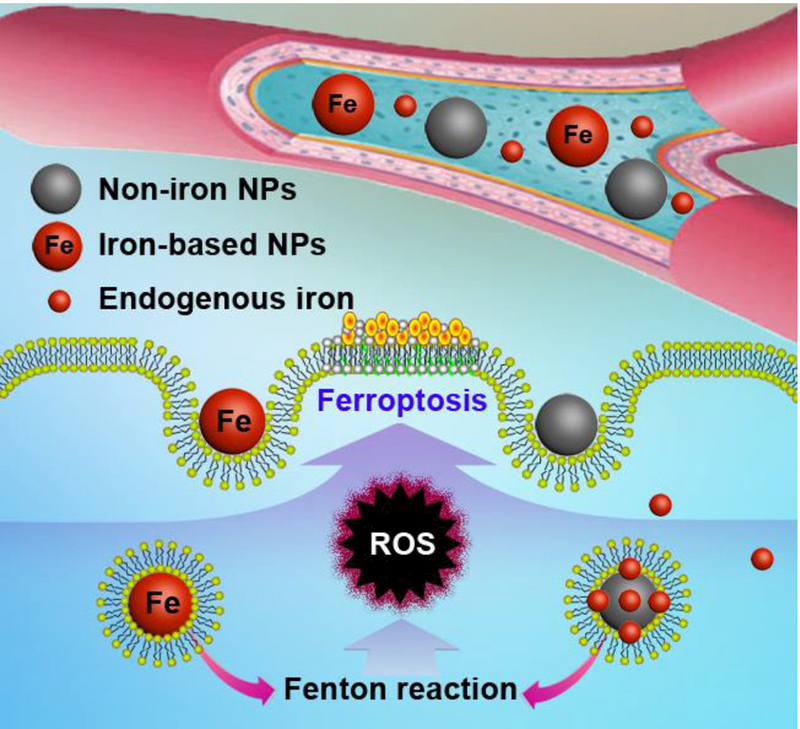

Most of the reported nanomaterials that can be used for the ferroptosis-based cancer therapy are iron-based nanomaterials because they are able to specifically accumulate at the tumor site via passive targeting and active targeting, and the iron can be released in the acidic lysosome as ferrous (Fe2+) or ferric (Fe3+) ions, which participate in the Fenton reaction and induce ferroptosis to kill the cancer cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanism scheme of the iron-based and indirect iron-based nanomaterials for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy. These nanomaterials can release their own iron or loaded endogenous iron in lysosome after endocytosis, which can be involved in the Fenton reaction to produce ROS and induce lipid peroxidation.

3.1.1. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (IO NPs)

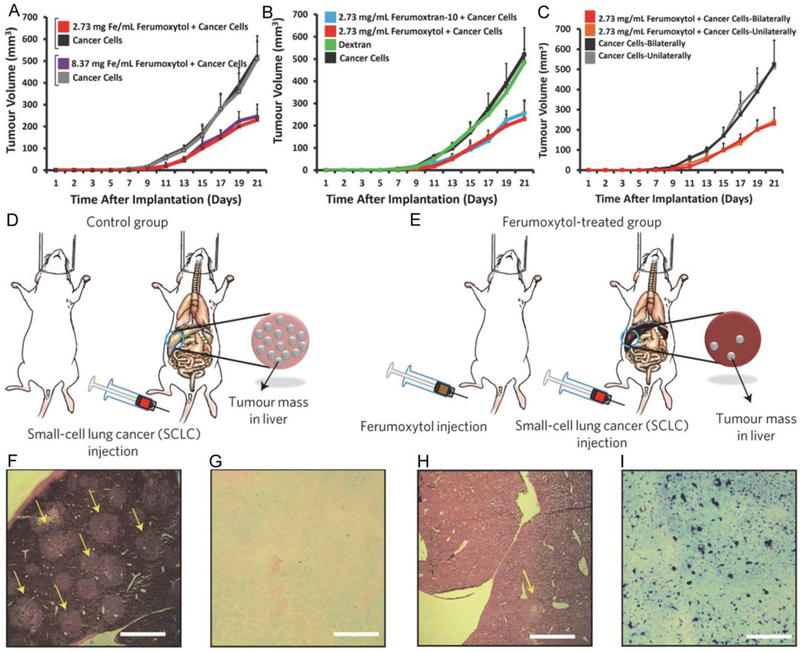

Ferumoxytol is an intravenous preparation of iron oxide nanoparticles (IO NPs) approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of iron deficiency in the clinic.[42–44] Zanganeh et al. showed an intrinsic therapeutic effect of ferumoxytol on the growth of early mammary cancers and lung cancer metastases in the liver and lungs.[45] In vitro, adenocarcinoma cells co-incubated with ferumoxytol and macrophages showed increased caspase-3 activity. Macrophages exposed to ferumoxytol displayed increased mRNA associated with pro-inflammatory Th1-type responses. In vivo, ferumoxytol significantly inhibited the growth of subcutaneous adenocarcinomas in mice as shown in Figure 3A-C. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and histopathology studies showed that the observed tumor growth inhibition was accompanied by increased presence of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages in the tumor tissues. Pretreatment with ferumoxytol can also inhibit the development of liver metastases (Figure 3D-I). It has been previously reported that the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages in wounds release H2O2,[46] which reacts with Fe3+ or Fe2+ to generate highly toxic ROS (i.e. •OH or •OOH) via the Fenton reaction that is shown in equations (1) and (2).

Figure 3.

A-C: Inhibition of tumor growth by the ferumoxytol (i.e. IO NPs). 2.3 × 106 MMTV-PyMT-derived cancer cells were inoculated to mice in the mammary fat pad with and without IO NPs. A: Tumor growth inhibited by the Ferumoxytol compared with controls (untreated) with 2 different concentrations of iron. B: Tumor growth inhibited by 2 different IO NPs (i.e. ferumoxytol, and ferumoxytran-10) compared with controls (untreated, or dextran only). C: Growth of the tumors inoculated unilaterally or bilaterally with 2.3 × 106 MMTV-PyMT-derived cancer cells in the mammary fat pad, with or without co-implantation of ferumoxytol (2.73 mg Fe / mL). Mean ± SD, n = 7. D,E: Inhibition of the liver metastases development by pretreatment with the ferumoxytol. Experimental methods: mice were injected with either saline (left) or ferumoxytol (3 × 10 mg Fe per kg−1; right), followed by intravenous injection of 1 × 104 KP1-GFP-Luc cells. F-I: Corresponding histopathology: representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained images show marked tumor cell infiltration (yellow arrows) of a normal liver (control) (F), but not for a liver treated with ferumoxytol (H). Prussian blue stains show almost no iron deposition in an untreated liver (control) (G), but obvious iron deposition in a liver treated with ferumoxytol (I). Scale bars, 1 mm. Reproduced with permission.[45] Copyright 2016, Nature Publishing Group.

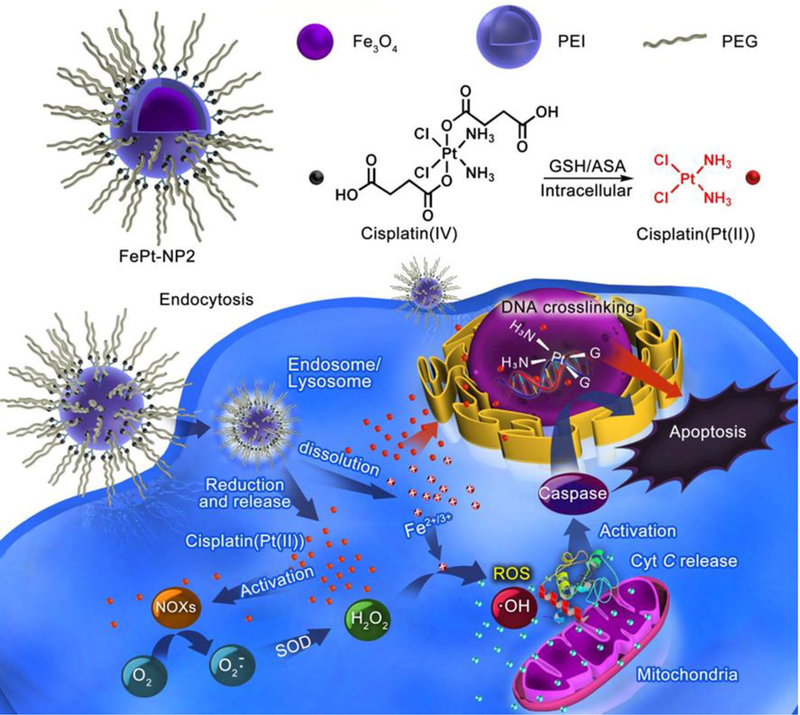

3.1.2. Cisplatin-Loaded IO NPs

Ma et al. proposed a sequential drug delivery strategy utilizing intracellular iron ions released from the IO NPs to enhance sensitivity to cisplatin, which is co-delivered by the IO NPs, for enhancing anticancer efficacy.[47] Construction of various IO NPs without Pt drugs by coating with polyethylenimine (PEI) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Fe-NP1, bare iron NPs; Fe-NP2, PEI-coated NPs; Fe-NP3, PEG conjugate PEI coated NPs) was first achieved. Later, loading with cisplatin(IV) prodrugs, PEG, or rhodamine B (RhB) dye yielded iron oxide NPs with different functionalities (FePt-NP1, Pt loaded iron NPs; FePt-NP2, PEGylated Pt loaded iron NPs; FePt-NP3, RhB labeled FePt-NP2). The final cisplatin-(IV) prodrugs loaded with self-sacrificing iron-oxide NPs were FePt-NP2 with PEG on the surface (Figure 4). Here, the cisplatin mediates activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX), which triggers oxygen (O2) conversion to superoxide radical (O2•−) and its downstream transformation to H2O2. Through the Fenton reaction, H2O2 could be catalyzed by Fe2+/Fe3+ to the toxic hydroxyl radical (•OH), which causes oxidative damages to lipids, proteins, and DNA. By taking full advantage of Fenton chemistry, Ma et al. demonstrated tumor site-specific conversion of ROS generation induced by released cisplatin and Fe2+/Fe3+ from IO NPs with cisplatin(IV) prodrugs for enhanced anticancer activity, but minimized systemic toxicity. In addition, unlike cisplatin, the nanoparticles are internalized into cells via endocytosis, which contributes to the reversal of the cell’s resistance to cisplatin.[47]

Figure 4.

Schematic design of self-sacrificing IO NPs with cisplatin (IV) prodrug (FePt-NP2). The released cisplatin after endocytosis can activate NOXs that catalyze formation of H2O2 from O2. Both the formed H2O2 and the released Fe2+/3+ induce ROS via Fenton reaction, which results in fast lipid and protein oxidation and DNA damage. Reproduced with permission.[47] Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

3.1.3. Lipid Hydroperoxide-Tethered IO NPs

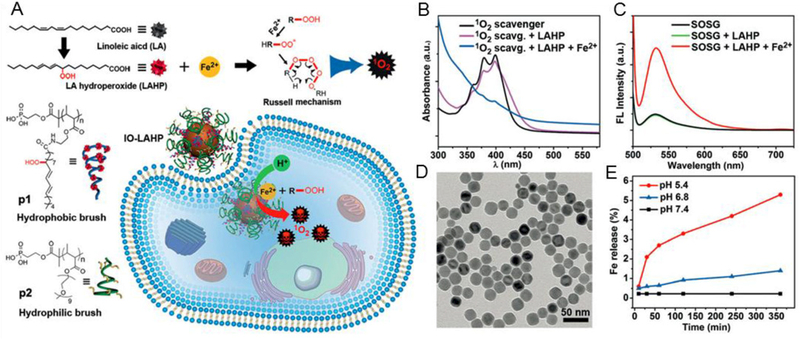

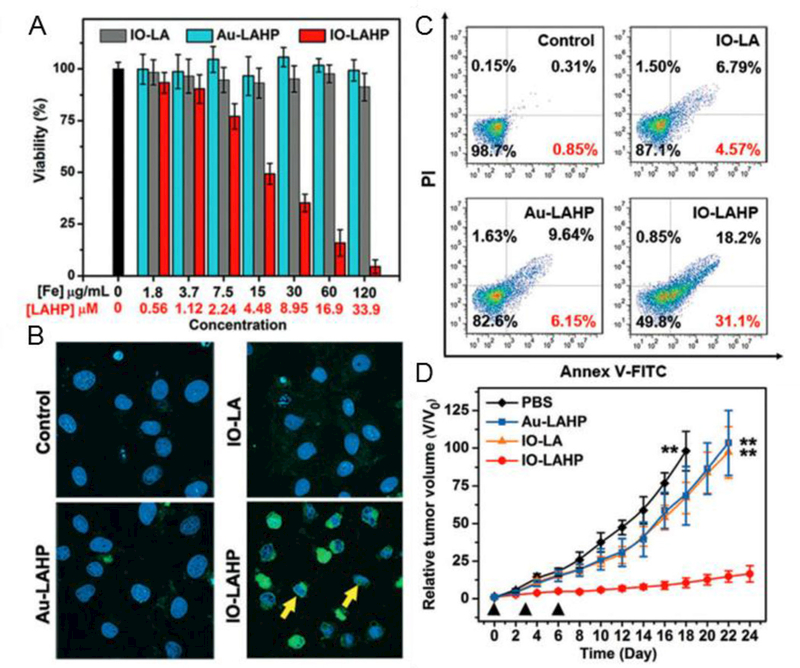

Zhou et al. reported an activatable singlet oxygen (1O2) generating system for specific cancer therapy under tumor acidic pH environment through engineering the reaction between linoleic acid hydroperoxide (LAHP) and catalytic iron (II) ions. LAHP is one of the primary products of lipid peroxidation, which is associated with several diseases by decomposition into ROS and 1O2 in the presence of Fe2+ through the Russell mechanism (Figure 5A).[48] Herein, IO NPs were employed as vehicles to carry LAHP polymers with a surface-anchoring group. H+ could penetrate the polymer brushes and dissociate Fe2+ from the surface of IO-LAHP NPs, thus triggering the formation of ROS and 1O2 and leading to cancer cell death (i.e. ferroptosis). A UV-based singlet oxygen scavenger 9,10-diphenylanthracene (DPA)-derived sensor and fluorescent (FL) singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) were developed to measure the efficient production of 1O2 species by iron (II)-catalyzed decomposition of LAHP molecules (Figure 5B, C). The results showed that 2.1% of iron ions were dissolved from IO-LAHP NPs (22 nm, Figure 5D) within the first 30 min incubation period, which reached a value of 5.3% after 24 h under pH 5.4 (Figure 5E). The results of cell viability study (Figure 6A), confocal microscopy imaging (Figure 6B), flow cytometry study (Figure 6C), and tumor growth inhibition curves (Figure 6D) demonstrate the good efficacy of the ferroptosis-based cancer therapy.[48]

Figure 5.

A: Schematic generation of 1O2 via a chemical reaction between LAHP and catalytic ions (i.e. Fe2+) by the Russell mechanism. IO-LAHP NPs were fabricated by tethering phosphate group terminated hydrophobic (p1) and hydrophilic (p2) polymer brushes on surface. After internalization with cancer cells, the release of Fe2+ ions under acidic environment generate 1O2 species which exert cancer cell death through ROS mediated mechanism. B, C: UV and FL detection of 1O2 generation by 1O2 scavenger and SOSG. D: TEM image of IO NPs of Wustite-magnetite mixed phases with diameter of about 22 nm. E: Release profiles of iron ions from the IO-LAHP NPs under different pH values of 5.4, 6.8, and 7.4, respectively. Reproduced with permission.[48] Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH.

Figure 6.

A: Cell viability study in U87MG cell model after incubation with PBS, IO-LAHP, Au-LAHP, or IO-LA NPs for 48 h. The doses of Au-LAHP NPs were normalized to LAHP molecules. Values are mean ± s.d. (n = 3). B: Merged confocal microscopy images of cells incubated with different formulations for 24 h and stained with DAPI and TUNEL-FITC. Yellow arrows show the size shrinkage and shape abnormality of cell nucleus. C: Flow cytometry study of cells treated with different formulations for 24 h and stained with Annex V-FITC/PI apoptosis kit. Values indicate the percentages of early apoptotic cells. D: Overall tumor growth inhibition curves of mouse group treated with different formulations with total of three doses every three days (black triangles). Data represents mean ± s.d. (n = 5 / group, **P < 0.01). Reproduced with permission.[48] Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH.

3.1.4. Assembled IO NPs

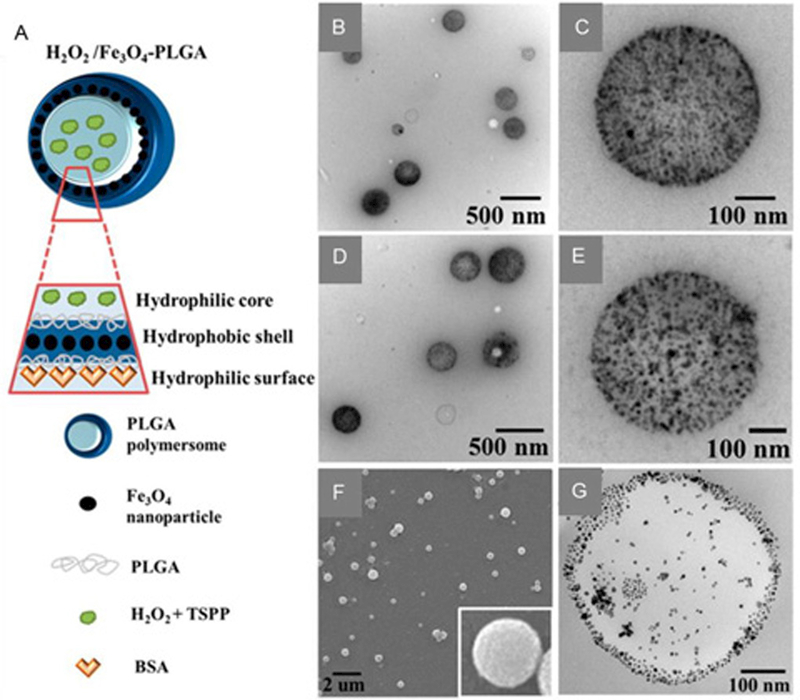

Li et al. prepared assembled IO NPs (Fe3O4 NPs) (i.e. packed IO NPs in the shell of a PLGA polymersome), and encapsulated H2O2 in the hydrophilic core of the polymersome (Figure 7A).[49] The structure of the formulated H2O2/Fe3O4−PLGA polymersomes were verified by TEM, SEM, and Cryo-TEM images (Figure 7B-G). The encapsulation of H2O2 plays a crucial role in concurrently providing O2 for echogenic reflectivity and •OH as the therapeutic ROS. Upon exposure to the micro-US diagnostic system, the encapsulated H2O2 in the core was liberated and moved through the disrupted PLGA polymersome to react with Fe3O4 packed inside the polymersome membrane, thus yielding •OH via Fenton reaction. Their results showed that malignant tumors could be completely removed under a non-thermal process.

Figure 7.

A: Schematic preparation of Fe3O4-embedded and H2O2-encapsulated PLGA polymersomes (H2O2/Fe3O4-PLGA) by a double-emulsion process. B: TEM image of the Fe3O4-PLGA polymersomes. C: high-magnification TEM image of a single Fe3O4-PLGA polymersome. D: TEM image of the H2O2/Fe3O4-PLGA polymersomes. E: high-magnification image of a single H2O2/Fe3O4-PLGA polymersome. F: SEM image of the H2O2/Fe3O4-PLGA polymersomes. The inset is a high magnification image of a single H2O2/Fe3O4-PLGA polymersome. G: Cryo-TEM image of a single H2O2/Fe3O4-PLGA polymersome with a hollow structure. Reproduced with permission.[49] Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society.

3.1.5. Amorphous Iron Nanoparticles (AFeNPs)

Since their inception in 1960, amorphous metals and alloys, which can also be described as metallic glasses with a disordered atomic structure, have attracted great attention owing to their extraordinary properties.[50]

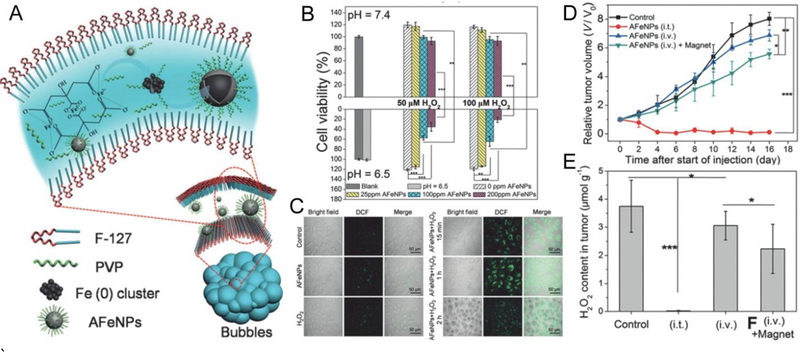

Considering the reactive nature of metallic glasses, which is due to the metastable random structure that is devoid of long-range order, Zhang et al. synthesized amorphous iron (Fe0) nanoparticles (AFeNPs) for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy. They reported on a design and facile synthesis of AFeNPs as shown in Figure 8A.[51] The in vitro studies demonstrated that the AFeNPs can be used for cancer therapy in the presence of H2O2 at pH 6.5 (Figure 8B, C). The tumor growth can be inhibited by the AFeNPs that can induce a Fenton reaction in the tumor by taking advantage of the mild acidity and the overproduced H2O2 in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 8D, E). Ionization of the AFeNPs enables on-demand ferrous ion release in the tumor, and the subsequent H2O2 disproportionation leads to efficient radical generation (•OH or •OOH). The endogenous stimuli-responsive radical generation in the presence of AFeNPs enables a highly specific cancer therapy without the need for external energy input.[51]

Figure 8.

A: Schematic design of the AFeNPs. B: Cell viabilities of the MCF-7 cells with incubation of AFeNPs at pH 7.4 and 6.5 with various concentrations of H2O2 (mean ± S.D., n = 6, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). C: Confocal images of MCF-7 cells (stained with DCFH-DA) treated with AFeNPs only, H2O2 only, and both at pH 6.5. D: Change of the relative tumor volume after different treatments (mean ± S.D., n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). E: Change of the H2O2 concentration in the tumor after different treatments (mean ± S.D., n = 3, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Intratumoral AFeNP injection: (i.t.); intravenous AFeNP injection without magnetic targeting: (i.v.); intravenous AFeNP injection with magnetic targeting: (i.v.) + magnet. Reproduced with permission.[51] Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH.

3.1.6. Iron-Organic Frameworks

Metal-organic frameworks (MOF), or metal-organic networks (MON), have emerged as an extensive class of crystalline materials with ultrahigh porosity (up to 90% free volume) and enormous internal surface areas, extending beyond 6000 m2/g.[52,53] These properties, together with the extraordinary degree of variability for both the organic and inorganic components of their structures, make MOF a valuable tool for potential applications in membranes, thin film devices, catalysis, and anticancer agents.[54]

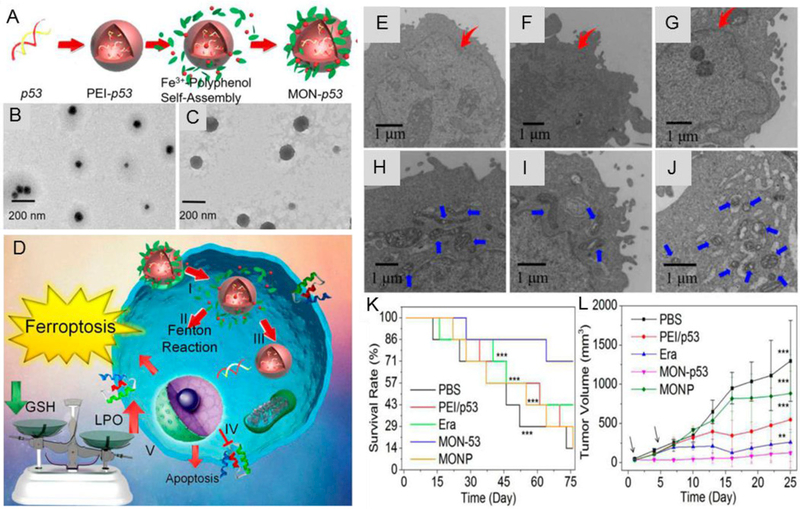

By harnessing the recently discovered oxidative stress regulation ability of p53 and the Fenton reaction inducing capability of MON, Zheng et al. encapsulated p53 plasmid into MON (MON-p53) to eradicate cancer cells via the ferroptosis/apoptosis hybrid pathway.[55] As shown in Figure 9A, tannic acid, a FDA approved food additive extracted from green tea, was combined with ferric ions to form MON on the surface of the PEI/p53 plasmid complex (PEI/p53) (Figure 9B), obtaining MON-p53 (Figure 9C), and MON coating was used to enhance the ferroptosis inducing ability of p53. As shown in Figure 9D, once MON-p53 was internalized, ferric ions could induce Fenton reaction to produce ROS, and high intracellular ROS concentration could cause serious lipid peroxidation in biomembranes. Meanwhile, the expressed p53 protein further inhibited lipid peroxide elimination. The morphological changes of PEI/p53, or MON-p53 treated HT1080 cells indicate that cells suffered from ferroptosis during the cell death (Figure 9E-J). As shown in Figure 9K, MON-p53 treatment significantly prolonged the median survival time from 44.5 days (PBS treated mice) to 75 days (MON-p53 treated mice). Besides, MON-p53 treatment was found to have a higher efficiency in inhibiting tumor growth than PEI/p53, MONP (metal-organic nanoprecipitate), or PBS treatments (Figure 9L).[55]

Figure 9.

A: Schematic design of MON-p53. B: TEM images of PEI/p53. C: TEM images of MON-p53. D: Schematic illustration of the anticancer therapy by MON-p53. (I) Endocytosis of MON-p53. (II) Fenton reaction induced by MON. (III) Transfection and expression of p53 protein. (IV) Inhibition of transmembrane SLC7A11 protein mediated by p53 protein. (V) Fenton reaction regulated LPO accumulation and SLC7A11 inhibition induced GSH depletion caused ferroptosis; p53 protein regulated apoptosis pathway and cause apoptosis. (E-G): Cells morphology with PEI/p53 (with a p53 content of 2 μg/mL) mediated apoptosis. (H-J): Cells morphology with MON-p53 mediated ferroptosis (with a p53 content of 2 μg/mL). K: Survival curves of mice receiving injections of Era at a dose of 5 mg/kg, MONP at a dose of 5 mg/kg, and DNA dose of 0.375 mg/kg (n = 7 for all groups) in HT1080 tumor bearing mice. L: HT1080 tumor volume curves of mice at the first 25 days. Reproduced with permission.[55] Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

3.1.7. FePt Nanoparticles

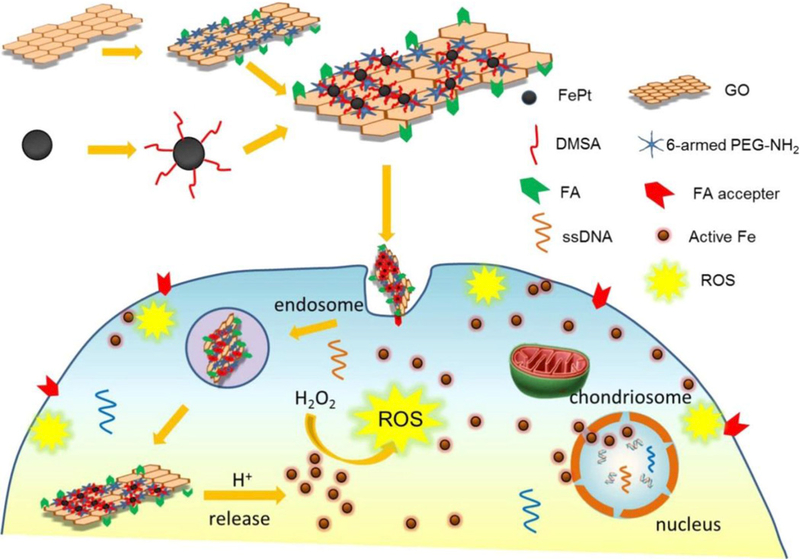

Yue et al. developed a FePt nanoparticle based pH-responsive multifunctional theranostic agent for dual modal MRI/CT imaging and in situ cancer inhibition.[56] The FePt nanoparticles released highly active Fe ions due to the low pH in tumor cells, which could catalyze H2O2 decomposition into ROS within the cells and further induce cancer cell ferroptosis. After conjugation with folic acid (FA), the iron platinum-dimercaptosuccinnic acid/PEGylated graphene oxide-folic acid (FePt-DMSA/GO-PEGFA) composite nanoassemblies (FePt/GO CNs) (Figure 10) could effectively target and exert significant toxicity (i.e. ferroptosis) to FA receptor-positive tumor cells, but no obvious toxicity to FA receptor-negative normal cells was detected. In addition, the decomposition of FePt nanoparticles dramatically decreased the T2-weighted MRI signal and increased the ROS signal, which enabled real-time and in situ visualization of Fe release in tumor cells.[56]

Figure 10.

The pH-responsive theranostic probe and its active intracellular Fe release process. FePt/GO CNs enter the tumor cells via folate receptor-mediated endocytosis, subsequently Fe is released from FePt due to the acidic stimuli in tumor cells, and the released Fe catalyzes H2O2 into ROS (Fenton reaction), which could damage the cellular membranes, eventually leading to ferroptosis. Reproduced with permission.[56] Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

3.2. Indirect Iron-Based Nanomaterials

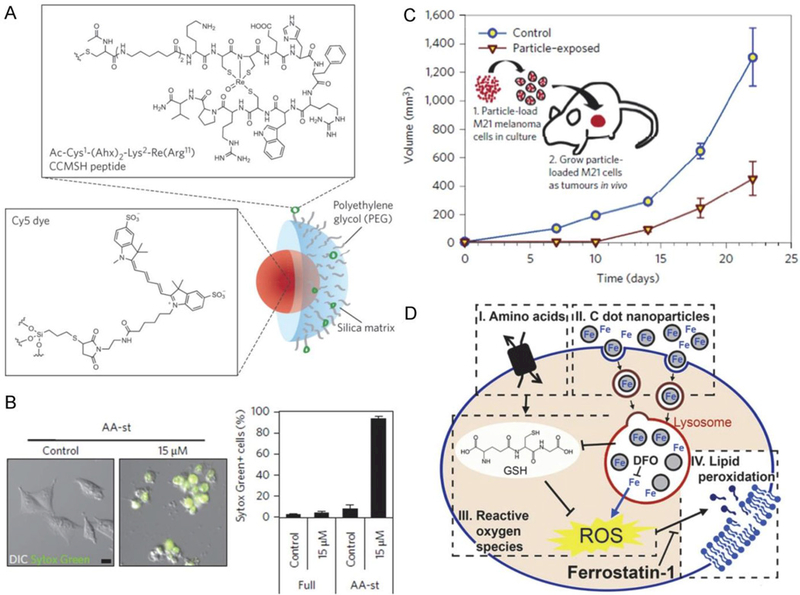

There are a wide variety of non-iron nanomaterials being investigated for biomedical applications.[57–59] However, up to now, very little research on indirect iron-based nanomaterials for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy has been reported because iron is a key component for ferroptosis based on the Fenton reaction. For the first time, Kim et al. demonstrated that indirect iron-based nanomaterials can also be developed for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy because they can load and transfer the endogenous iron into cells.[60] The indirect iron-based nanomaterials were designed to be ultrasmall αMSH-PEG-C’ dots (6 nm) with a fluorescent (Cy5 encapsulated) core and polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating and alpha melanocytestimulating hormone (αMSH)-modified exterior (Figure 11A). Figure 11B showed live control cells and dead (Sytox Green+) nanoparticle-treated cells in amino acid-starved (AA-st) conditions. The results demonstrated that while αMSH-PEG-C’ dots are generally well tolerated, nutrient-deprived cancer cells are sensitive to treatment (Figure 11C). The cell death induced by treatment of αMSH-PEG-C’ dots under conditions of nutrient deprivation was further verified to be ferroptosis, but not apoptosis, necroptosis, or autosis. As shown in Figure 11D, the nanoparticle-induced ferroptosis was observed following iron uptake into cells, suppression of glutathione, and accumulation of lipid ROS. Lipid ROS may accumulate in glutathione-suppressed cells due to the lowered activity of GPX4 enzyme that protects cells from lipid peroxidation and inhibits ferroptosis.

Figure 11.

A: Design of the non-iron ultrasmall αMSH-PEG-C’ dots (6-nm) with a fluorescent (Cy5 encapsulated) core and polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating and alpha melanocytestimulating hormone (αMSH)-modified exterior. B: Nanoparticle treatment induces cell death of M21 cells cultured in amino-acid-free media. C: M21 cells treated with 15 μM αMSH-PEG-C’ dots in full media for 72 h before creating xenografts in immunodeficient (SCID/Beige) mice demonstrate growth inhibition (inverted triangles) relative to untreated control cells (circles). Schematic shows workflow, consisting of (1) particle-loading M21 melanoma cells, by treatment at 15 μM for 48 h in culture under full media conditions, and (2) injecting 5 × 106 particle-loaded M21 cells into mice to assay xenograft tumor growth versus control untreated cells. D: The nanoparticle-induced ferroptosis is executed following iron uptake into cells, suppression of glutathione, and accumulation of lipid ROS. Lipid ROS may accumulate in glutathione-suppressed cells due to lowered activity of the glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) enzyme that protects cells from lipid peroxidation and inhibits ferroptosis. Reproduced with permission.[60] Copyright 2016, Nature Publishing Group.

4. Gene Technologies for Ferroptosis-Based Cancer Therapy

Recently, genes have been identified as a requisite for the induction or inhibition of ferroptosis via their encoding proteins. Therefore, gene technologies can be developed for ferroptosis-based cancer therapies. According to the induction or inhibition of ferroptosis, these technologies can be classified to two categories: gene transfection technologies and gene knockdown technologies.

Tumor suppression through the p53 pathway is an important way to inhibit the formation of most human cancers.[61] Conventionally, the p53 tumor suppression activity was considered to reflect its ability to elicit cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and/or senescence in response to cellular stress. Besides, recent research results also demonstrated that some activities other than traditional p53 are also very important for its function of tumor suppression.[61,62] Jiang et al. found that ferroptosis is also a p53-mediated activity during tumor suppression.[63] They showed that p53 inhibits cystine uptake and sensitizes cells to ferroptosis by repressing expression of SLC7A11, which is a key component of the cystine/glutamate antiporter. Remarkably, p533KR, an acetylation-defective mutant that fails to induce cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis, fully retains the ability to regulate SLC7A11 expression and induce ferroptosis upon ROS-induced stress. Analysis of mutant mice showed that these non-canonical p53 activities contribute to embryonic development and the lethality associated with loss of Mdm2. Moreover, SLC7A11 is highly expressed in human tumors, and its overexpression inhibits ROS-induced ferroptosis and abrogates p533KR-mediated tumor growth suppression in xenograft models.[63] These findings uncover a new mode of tumor suppression based on gene transfection (i.e. p53 regulation of cystine metabolism, ROS responses, and ferroptosis).[63–65]

Furthermore, Wang et al. demonstrated that K98 acetylation of mouse p53 by CREB-binding protein (CBP) further contributes to the regulation of p53 transcriptional function by other known p53 acetylations (K117/161/162).[66] Simultaneous absence of acetylation at K98 and at other positions in the DNA-binding domain results in the loss of tumor suppression in xenografts and ferroptosis.[66]

The acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) was also demonstrated to be an essential proferroptotic gene.[18,67] Doll et al. applied two independent approaches (i.e. a genome-wide CRISPR-based genetic screen and microarray analysis of ferroptosis-resistant cell lines) to uncover ACSL4 as an essential component for ferroptosis execution.[18] Specifically, GPX4-ACSL4 double knockout cells showed marked resistance to ferroptosis. Mechanistically, ACSL4 enriched cellular membranes with long polyunsaturated ω6 fatty acids. Moreover, ACSL4 was preferentially expressed in a panel of basal-like breast cancer cell lines and predicted their sensitivity to ferroptosis.[18]

Yuan et al. also demonstrated that ACSL4 is required for ferroptotic cancer cell death.[67] Compared with ferroptosis-sensitive cells (e.g. HepG2 and HL60), the expression of ACSL4 was remarkably downregulated in ferroptosis-resistant cells (e.g. LNCaP and K562). In contrast, the expression of other ACSLs, including ACSL1, ACSL3, ACSL5, and ACSL6, did not correlate with ferroptosis sensitivity. Moreover, knockdown of ACSL4 by specific shRNA inhibited erastin-induced ferroptosis in HepG2 and HL60 cells, whereas overexpression of ACSL4 by gene transfection restored the sensitivity of LNCaP and K562 cells to erastin. Mechanistically, ACSL4-mediated production of 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE) contributed to ferroptosis. Pharmacological inhibition of 5-HETE production by zileuton limited ACSL4 overexpression-induced ferroptosis.[67] These results indicate that ACSL4 is not only a sensitive indicator of ferroptosis, but also an important contributor of ferroptosis.

Collectively, some genes (e.g. p53, ACSL4) are important contributors to ferroptosis by repressing or promoting the overexpression of some key proteins. Therefore, transfection of these genes to tumors may be used for ferroptosis-based cancer therapies.

It is also reported that some genes inhibit ferroptosis by expression of some important proteins. For example, Sun et al. reported that upon exposure to ferroptosis-inducing compounds (e.g., erastin, sorafenib, and buthionine sulfoximine), p62 expression prevented NRF2 degradation and enhanced subsequent NRF2 nuclear accumulation through inactivation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1).[68] Additionally, nuclear NRF2 interacted with transcriptional coactivator small avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (v-maf) oncogene homolog proteins such as MafG and then activated transcription of quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and ferritin heavy chain-1 (FTH1). Knockdown of genes corresponding to these proteins by RNA interference in HCC cells promoted ferroptosis in response to erastin and sorafenib and increased the anticancer activity of erastin and sorafenib.[68]

Yuan et al. proposed that CDGSH iron sulfur domain 1 (CISD1, also termed mitoNEET), which is an iron-containing outer mitochondrial membrane protein, negatively regulates ferroptotic cancer cell death.[69] The classical ferroptosis inducer erastin promotes CISD1 expression in an iron-dependent manner in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (e.g., HepG2 and Hep3B). Genetic inhibition of CISD1 increased iron-mediated intramitochondrial lipid peroxidation, which contributes to erastin-induced ferroptosis.[69]

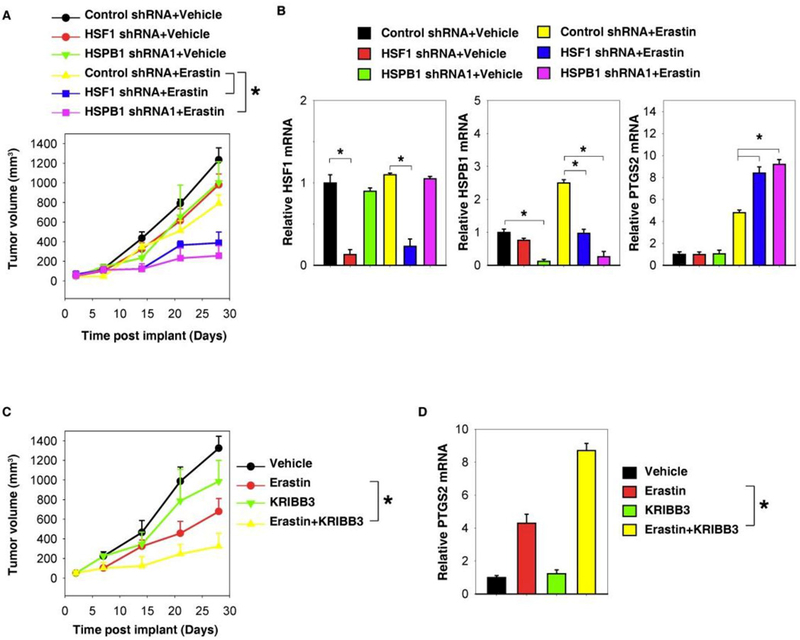

Sun et al. demonstrated that heat shock protein beta-1 (HSPB1) is a negative regulator of ferroptotic cancer cell death.[70] Erastin, a specific ferroptosis-inducing compound, stimulates heat shock factor 1 (HSF1)-dependent HSPB1 expression in cancer cells. Compared with the control shRNA group, erastin treatment effectively reduced the size of tumors formed by HSF1 and HSPB1 knockdown cells (Figure 12a). The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis of the expression of PTGS2, a marker for assessment of ferroptosis in vivo, indicated that the knockdown of HSF1 and HSPB1 increases ferroptosis (Figure 12b). Moreover, KRIBB3, an inhibitor of protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of HSPB1, exhibited a dose-dependent increase of erastin-induced tumor inhibition (Figure 12c), which was associated with an increased PTGS2 messenger RNA expression (Figure 12d). Together, these findings demonstrated that knockdown of HSF1 and HSPB1 enhances erastin-induced ferroptosis, whereas heat shock pretreatment and overexpression of HSPB1 inhibits erastin-induced ferroptosis. Inhibition of the HSF1-HSPB1 pathway and HSPB1 phosphorylation increases the anticancer activity of erastin in human xenograft mouse tumor models.[70]

Figure 12.

Inhibition of the HSF1-HSPB1 pathway increases anticancer activity of erastin in vivo. (a) HSF1 and HSPB1 knockdown HeLa cells were more sensitive to erastin in vivo. SCID mice were injected subcutaneously with indicated HeLa cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) and treated with erastin (20 mg/kg intravenously, twice every other day) at day 7 for 2 weeks. Tumor volume was calculated weekly. (b) The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis of the indicated gene expression in isolated tumor at day 28. (c) KRIBB3 increased anticancer activity of erastin in vivo. SCID mice were injected subcutaneously with indicated HeLa cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) and treated with erastin (20 mg/kg intravenously, twice every other day) with or without KRIBB3 (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally, once every other day) at day 7 for 2 weeks. Tumor volume was calculated weekly. (d) The qPCR analysis of the PTGS2 gene expression in isolated tumor at day 28. (Mean ± S.E., n=5~8 mice/group, *P < 0.05). Reproduced with permission.[70] Copyright 2016, Nature Publishing Group.

Overall, some genes (e.g. p62, CISD1, HSF1 and HSPB1) are negative regulators of ferroptotic cancer cell death. Knockdown of these genes by RNA interference in cancer cells may promote ferroptosis and increase the anti-cancer activity. Therefore, gene knockdown technologies may also be used for ferroptosis-based cancer therapies.

5. Conclusions and Future Prospective

Ferroptosis is a new form of cell death which was termed in 2012 for the first time. Since then, lots of research has focused on the cellular mechanisms and signaling pathways involving ferroptosis. Based on the clarified mechanisms, more researchers have begun to venture into the exciting field of discovering ferroptosis-inducing agents, which may provide new insights into designing materials for cancer therapy.

The discovered ferroptosis-inducing agents include genes, small molecules, and nanomaterials. The advantages of the gene-based ferroptosis cancer therapy include: 1) a number of exogenous genes can be delivered to work with the endogenous genes or some endogenous genes can be knocked out over a sustained period of time, unlike most drugs which require frequent administration. 2) It offers the prospect of a single dose, long-term, and possible cure for the cancer, which currently has poor clinical outcomes. However, the gene-based ferroptosis cancer therapy is essentially a kind of gene therapy, which is producing much controversy and raising many ethical and legal concerns. Therefore, although the gene-based ferroptosis cancer therapy is promising, there is still a long way to go before it can be used clinically.

The advantages of small molecules for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy include: 1) the shelf life of small molecules is relatively long, which allows facile storage and delivery. 2) The small molecules are easily metabolized or cleared from the body resulting in low long-term toxicity. However, there are also some limitations for the small molecule based ferroptosis in cancer therapy: 1) adverse effects of ferroptosis to normal tissues and cells may occur due to the low specificity of small molecules to tumors. 2) The circulating half-life in blood is short and the accumulation at tumor site is low due to rapid renal clearance.

Ferroptosis-inducing nanomaterials have been recently introduced. The advantages of nanomaterials for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy include: 1) the adverse effects of ferroptosis to normal tissues and cells can be reduced by the precise targetability of such nanomaterials including passive targeting and active targeting. Passive targeting facilitates deposition of nanomaterials within the tumor microenvironment, owing to distinctive characteristics inherent to the tumor vasculature, not normally present in healthy tissues (i.e. enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect).[71,72] The nanomaterials can also be functionalized with active targeting ability by conjugation of targeted molecules (antibodies or ligands).[73–75] 2) The large hydrodynamic size (> 6 nm) of the nanomaterials can reduce the renal clearance, prolong the circulating half-life in blood, and enhance the accumulation at tumor sites. However, the shelf life of the nanomaterials may be short due to the possibility of aggregation. In addition, the residual nanomaterials inside the body may pose a risk of long-term toxicity.

Up to now, there have been two types of nanomaterials reported for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy: iron-based nanomaterials, and indirect iron-based nanomaterials. The latter requires transfer of the limited endogenous iron into cells to cause ferroptosis based on the Fenton reaction. The reported indirect iron-based nanomaterials can only induce ferroptosis in nutrient-deprived cancer cells to accumulate ROS by glutathione (GSH) depletion and lower the activity of GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4). Therefore, it is hard for the indirect iron-based nanomaterials to obtain an excellent efficiency of ferroptosis-based cancer therapy.

The iron-based nanomaterials are more promising over the indirect iron-based nanomaterials because iron itself is a key component in the Fenton reaction to produce ROS. Since iron oxide nanoparticles (IO NPs) were reported to inhibit tumor growth through the Fenton reaction for the first time in 2016,[45] a number of new iron-based nanomaterials were developed for ferroptosis-based cancer therapy, such as H2O2-encapsulated assembled IO NPs,[49] cisplatin-loaded IO NPs,[47] lipid hydroperoxide-tethered IO NPs,[48] p53-encapsulated metal-organic networks (MON),[55] amorphous iron nanoparticles (AFeNPs),[51] and FePt nanoparticles.[56] These studies demonstrated that the Fenton reaction actually occurs in vivo. Compared with other iron-based nanomaterials, the AFeNPs can be more rapidly ionized in a weakly acidic tumor environment to release the iron ions on-demand and enable subsequent localized Fenton reaction for specific cancer therapy. However, in order to induce ferroptosis-based cancer treatment using the AFeNPs, the Fe dose needs to be very high, up to 75 mg/kg body weight (intravenous injection).[51] Because of this, most of the reported iron-based nanomaterials need to include another component (beyond iron) that contributes to the ferroptosis, such as the H2O2-encapsulated assembled IO NPs, lipid hydroperoxide-tethered IO NPs, and p53-encapsulated MON. For the H2O2-encapsulated assembled IO NPs, the released H2O2 from the assembled IO NPs in tumors act as a reactant of the Fenton reaction that can directly promote ROS formation. For the lipid hydroperoxide-tethered IO NPs, the lipid hydroperoxide can be decomposed into ROS and singlet oxygen (1O2) in the presence of the released iron ions (i.e. catalytic ions). For the p53-encapsulated MON, the expressed p53 protein inhibits lipid peroxide elimination, which benefits the accumulation of ROS. With additional components besides iron, the Fe dose of these iron-based nanomaterials can be lowered to 3 ~ 5 mg/kg body weight, which makes ferroptosis cancer therapy feasible and practical.

In the future, there will be strategic opportunities to enhance the efficacy of ferroptosis-based cancer therapy by associating the iron-based nanomaterials with other components that contribute to ferroptosis. The iron-based nanomaterials could be used as delivery carriers of some genes (e.g. p53, ACSL4) by repressing or promoting the overexpression of some key proteins related to ferroptosis. Loading small molecules that can induce ferroptosis in cancer cells onto IO NPs are also good choices for the ferroptosis-based cancer therapy because the iron-based nanomaterials can enhance the specificity of small molecules to tumors, and prolong the circulation half-life in blood. It is appealing to combine efforts from research communities of biochemistry, oncology, and especially material science to pursue rational design of effective cancer therapy strategies based on ferroptosis.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (2016269) (Z. S.), Intramural Research Program (IRP), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant No. ZIA EB000073), Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project of Zhejiang Province (2017C33129), the National Key Research & Development Program (2016YFC1400600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51761145021, 61571278 and 21305148), Bureau of Science and Technology of Ningbo Municipality City (Grant Nos. 2015B11002), and NSFC-Guangdong Province Joint Project on National Supercomputer Centre in Guangzhou (NSCC-GZ) (A. W.).

Biographies

Dr. Zheyu Shen is a visiting scholar of the National Institutes of Health (USA) under the supervision of Prof. Xiaoyuan Chen. He earned his PhD from the Institute of Process Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, under the supervision of Prof. Guanghui Ma and Prof. Toshiaki Dobashi (Gunma University, Japan). After postdoctoral studies with Prof. Kazuhiro Kohama (Gunma University, Japan) and Prof. Sheng Dai (The University of Adelaide, Australia), he was appointed an Associate Professor (2012) and promoted to Full Professor (2015) at the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology & Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences. His research interests include: cancer theranostics, molecular imaging, circulating tumor cells.

Prof. Aiguo Wu received his PhD from the Chinese Academy of Sciences supervised by Prof. Erkang Wang and Prof. Zhuang Li in China in 2003. He stayed in the University of Marburg (Prof. Norbert Hampp group) in Germany during 2004–2005, Caltech (Prof. Ahmed Zewail group) during 2005–2006, and Northwestern University (Prof. Gayle Woloschak group) during 2006–2009. In 2009, he joined NIMTE, CAS as a PI. Prof. Wu has published over 110 papers, one book, and three book chapters, and has been awarded 41 patents. His lab focuses on using nanoprobes for early diagnosis and therapy of diseases.

Prof. Xiaoyuan Chen received his PhD in Chemistry from the University of Idaho (1999). He started his Assistant Professorship at the University of Southern California in 2002 and then moved to Stanford University in 2004. He joined the NIH in 2009 as a Senior Investigator and Chief of the Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine (LOMIN) at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), NIH. His current research interests include the development of a molecular imaging toolbox for better understanding of biology, early diagnosis of disease, monitoring therapy response, and guiding drug discovery/development. His lab puts special emphasis on high-sensitivity nanosensors for biomarker detection and theranostic nanomedicine for imaging, gene and drug delivery, and monitoring of treatment.

Contributor Information

Dr. Zheyu Shen, CAS Key Laboratory of Magnetic Materials and Devices, & Key Laboratory of Additive Manufacturing Materials of Zhejiang Province, & Division of Functional Materials and Nanodevices, Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1219 ZhongGuan West Road, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315201, China, aiguo@nimte.ac.cn, Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States, shawn.chen@nih.gov; zijian.zhou@nih.gov

Dr. Jibin Song, Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States, shawn.chen@nih.gov; zijian.zhou@nih.gov

Dr. Bryant C. Yung, Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States, shawn.chen@nih.gov; zijian.zhou@nih.gov

Dr. Zijian Zhou*, Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States, shawn.chen@nih.gov; zijian.zhou@nih.gov

Prof. Aiguo Wu*, CAS Key Laboratory of Magnetic Materials and Devices, & Key Laboratory of Additive Manufacturing Materials of Zhejiang Province, & Division of Functional Materials and Nanodevices, Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1219 ZhongGuan West Road, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315201, China, aiguo@nimte.ac.cn

Prof. Xiaoyuan Chen*, Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, United States, shawn.chen@nih.gov; zijian.zhou@nih.gov

References

- [1].Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison III B, Stockwell BR, Cell 2012, 149, 1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tan S, Schubert D, Maher P, Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2001, 1, 497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Doll S, Conrad M, IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seiler A, Schneider M, Forster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, Plesnila N, Kremmer E, Radmark O, Wurst W, Cell Metab 2008, 8, 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR, Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yang WS, Stockwell BR, Chem. Biol 2008, 15, 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Angeli JPF, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch A, Eggenhofer E, Basavarajappa D, Radmark O, Kobayashi S, Seibt T, Beck H, Neff F, Esposito I, Wanke R, Forster H, Yefremova O, Heinrichmeyer M, Bornkamm GW, Geissler EK, Thomas SB, Stockwell BR, O’Donnell VB, Kagan VE, Schick JA, Conrad M, Nat. Cell Biol 2014, 16, 1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, Kang R, Tang D, Cell Death Differ 2016, 23, 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Matsushita M, Freigang S, Schneider C, Conrad M, Bornkamm GW, Kopf M, J. Exp. Med 2015, 212, 555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Distefano AM, Martin MV, Cordoba JP, Bellido AM, D’Ippolito S, Colman SL, Soto D, Roldan JA, Bartoli CG, Zabaleta EJ, Fiol DF, Stockwell BR, Dixon SJ, Pagnussat GC, J. Cell Biol 2017, 216, 463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yagoda N, von Rechenberg M, Zaganjor E, Bauer AJ, Yang WS, Fridman DJ, Wolpaw AJ, Smukste I, Peltier JM, Boniface JJ, Smith R, Lessnick SL, Sahasrabudhe S, Stockwell BR, Nature 2007, 447, 864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X, Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dixon SJ, Stockwell BR, Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].D’Herde K, Krysko DV, Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X, Cell Res 2016, 26, 1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yu X, Long YC, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 30033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A, Prokisch H, Trumbach D, Mao G, Qu F, Bayir H, Fullekrug J, Scheel CH, Wurst W, ASchick J, Kagan VE, Angeli JPF, Conrad M, Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Neitemeier S, Jelinek A, Laino V, Hoffmann L, Eisenbach I, Eying R, Ganjam GK, Dolga AM, Oppermann S, Culmsee C, Redox Biol 2017, 12, 558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zille M, Karuppagounder SS, Chen Y, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Finger J, Milner TA, Jonas EA, Ratan RR, Stroke 2017, 48, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yu H, Guo P, Xie X, Wang Y, Chen G, J. Cell. Mol. Med 2017, 21, 648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Conrad M, Angeli JPF, Vandenabeele P, Stockwell BR, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2016, 15, 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lachaier E, Louander C, Godin C, Saidak Z, Baert M, Diouf M, Chauffert B, Galmiche A, Anticancer Res 2014, 34, 6417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Louandre C, Marcq I, Bouhlal H, Lachaier E, Godin C, Saidak Z, Francois C, Chatelain D, Debuysscher V, Barbare JC, Chauffert B, Galmiche A, Cancer Lett 2015, 356, 971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sun X, Niu X, Chen R, He W, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D, Hepatology 2016, 64, 488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lo M, Wang YZ, Gout PW, J. Cell. Physiol 2008, 215, 593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M, Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M, Smith SB, Ganapathy V, Maher P, Antioxid. Redox Signal 2013, 18, 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sehm T, Fan Z, Ghoochani A, Rauh M, Engelhorn T, Minakaki G, Dorfler A, Klucken J, Buchfelder M, Eyupoglu IY, Savaskan N, Oncotarget 2016, 7, 36021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ooko E, Saeed MEM, Kadioglu O, Sarvi S, Colak M, Elmasaoudi K, Janah R, Greten HJ, Efferth T, Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Eling N, Reuter L, Hazin J, Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Oncoscience 2015, 2, 517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Roh JL, Kim EH, Jang H, Shin D, Redox Biol 2017, 11, 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lin R, Zhang Z, Chen L, Zhou Y, Zou P, Feng C, Wang L, Liang G, Cancer Lett 2016, 381, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, Brown LM, Girotti AW, Cornish VW, Schreiber SL, Stockwell BR, Cell 2014, 156, 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS, Stockwell BR, eLife 2014, 3, e02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Krainz T, Gaschler MM, Lim C, Sacher JR, Stockwell BR, Wipf P, ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Abrams RP, Carroll WL, Woerpel KA, ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ma S, Henson ES, Chen Y, Gibson SB, Cell Death Dis 2016, 7, e2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schockel L, Glasauer A, Basit F, Bitschar K, Truong H, Erdmann G, Algire C, Hagebarth A, HGM Willems P, Kopitz C, Koopman WJH, Heroult M, Cancer Metab, 2015, 3, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Basit F, MPE van Oppen L, Schockel L, Bossenbroek HM, van Emst-de Vries SE, Hermeling JCW, Grefte S, Kopitz C, Heroult M, Willems PHGM, Koopman WJH, Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fenton HJH, J. Chem. Soc 1894, 65, 899. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dunford HB, Coordin. Chem. Rev 2002, 233-234, 311. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rubio-Navarro A, Carril M, Padro D, Guerrero-Hue M, Tarin C, Samaniego R, Cannata P, Cano A, Villalobos JM, Sevillano AM, Yuste C, Gutierrez E, Praga M, Egido J, Moreno JA, Theranostics 2016, 6, 896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Su YL, Fang JH, Liao CY, Lin CT, Li YT, Hu SH, Theranostics 2015, 5, 1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang Y, Chen J, Yang B, Qiao H, Gao L, Su T, Ma S, Zhang X, Li X, Liu G, Cao J, Chen X, Chen Y, Cao F, Theranostics 2016, 6, 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zanganeh S, Hutter G, Spitler R, Lenkov O, Mahmoudi M, Shaw A, Pajarinen JS, Nejadnik H, Goodman S, Moseley M, Coussens LM, Daldrup-Link HE, Nat. Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sindrilaru A, Peters T, Wieschalka S, Baican C, Baican A, Peter H, Hainzl A, Schatz S, Qi Y, Schlecht A, Weiss JM, Wlaschek M, Sunderkotter C, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, J. Clin. Invest 2011, 121, 985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ma P, Xiao H, Yu C, Liu J, Cheng Z, Song H, Zhang X, Li C, Wang J, Gu Z, Lin J, Nano Lett 2017, 17, 928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhou Z, Song J, Tian R, Yang Z, Yu G, Lin L, Zhang G, Fan W, Zhang F, Niu G, Nie L, Chen X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Li WP, Su CH, Chang YC, Lin YJ, Yeh CS, ACS Nano 2016, 10, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Klement W, Willens RH, Duwez P, Nature 1960, 187, 869. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhang C, Bu W, Ni D, Zhang S, Li Q, Yao Z, Zhang J, Yao H, Wang Z, Shi J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhang P, Hu C, Ran W, Meng J, Yin Q, Li Y, Theranostics 2016, 6, 948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yen SK, Padmanabhan P, Selvan ST, Theranostics 2013, 3, 986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zhou HC, Long JR, Yaghi OM, Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zheng DW, Lei Q, Zhu JY, Fan JX, Li CX, Li C, Xu Z, Cheng SX, Zhang XZ, Nano Lett 2017, 17, 284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yue L, Wang J, Dai Z, Hu Z, Chen X, Qi Y, Zheng X, Yu D, Bioconjugate Chem 2017, 28, 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yi H, Wang Z, Li X, Yin M, Wang L, Aldalbahi A, El-Sayed NN, Wang H, Chen N, Fan C, Song H, Theranostics 2016, 6, 1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kempen PJ, Greasley S, Parker KA, Campbell JL, Chang HY, Jones JR, Sinclair R, Gambhir SS, Jokerst JV, Theranostics 2015, 5, 631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shen J, Kim HC, Su H, Wang F, Wolfram J, Kirui D, Mai J, Mu C, Ji LN, Mao ZW, Shen H, Theranostics 2014, 4, 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kim SE, Zhang L, Ma K, Riegman M, Chen F, Ingold I, Conrad M, Turker MZ, Gao M, Jiang X, Monette S, Pauliah M, Gonen M, Zanzonico P, Quinn T, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS, Overholtzer M, Nat. Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Valente LJ, Gray DH, Michalak EM, Pinon-Hofbauer J, Egle A, Scott CL, Janic A, Strasser A, Cell Rep 2013, 3, 1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang SJ, Gu W, Curr. Opin. Oncol 2014, 26, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, Baer R, Gu W, Nature 2015, 520, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Kroemer G, Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, 1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Murphy ME, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wang SJ, Li D, Ou Y, Jiang L, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Gu W, Cell Rep 2016, 17, 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2016, 478, 1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D, Hepatology 2016, 63, 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2016, 478, 838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sun X, Ou Z, Xie M, Kang R, Fan Y, Niu X, Wang H, Cao L, Tang D, Oncogene 2015, 34, 5617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shen Z, Wu H, Yang S, Ma X, Li Z, Tan M, Wu A, Biomaterials 2015, 70, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Bazak R, Houri M, Achy S, Hussein W, Refaat T, Mol. Clin. Oncol 2014, 2, 904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wu X, Xia Y, Huang Y, Li J, Ruan H, Luo L, Yang S, Shen Z, Wu A, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 19928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ma X, Gong A, Xiang L, Chen T, Gao Y, Liang X, Shen Z, Wu A, J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Shen Z, Wei W, Tanaka H, Kohama K, Ma G, Dobashi T, Maki Y, Wang H, Bi J, Dai S, Pharmacol. Res 2011, 64, 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]