Abstract

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an empirically supported treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD) in adults, however fewer studies have examined outcomes in adolescents. This study tested the effectiveness of an intensive 1-month, residential DBT treatment for adolescent girls meeting criteria for BPD. Additionally, given well-established associations between BPD symptoms and childhood abuse, the impact of abuse on treatment outcomes was assessed. Participants were female youth (n = 53) aged 13–20 years (M = 17.00, SD = 1.89) completing a 1-month residential DBT program. At pre-treatment, participants were administered a diagnostic interview and self-report measures assessing BPD, depression, and anxiety symptom severity. Following one month of treatment, participants were re-administered the self-report instruments. Results showed significant pre- to post-treatment reductions in both BPD and depression symptom severity with large effects. However, there was no significant change in general anxious distress or anxious arousal over time. The experience of childhood abuse (sexual, physical, or both) was tested as moderator of treatment effectiveness. Although experiencing multiple types of abuse was related to symptom severity, abuse did not moderate the effects of treatment. Collectively, results indicate that a 1-month residential DBT treatment with adolescents may result in reductions in BPD and depression severity but is less effective for anxiety. Moreover, while youth reporting abuse benefitted from treatment, they were less likely to achieve a clinically significant reduction in symptoms.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Adolescents, Child Abuse, Residential Treatment

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by repetitive suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors, extreme emotion and behavioral dysregulation, and disruptions in interpersonal relationships (Linehan, 1993). Despite prior controversy around diagnosing personality disorders in youth, it has become increasingly evident that personality disorders can be reliably diagnosed in adolescents, showing good concurrent and predictive validity and similar stability as seen in adults (Becker et al., 1999; Bernstein et al., 2003; Chanen, Jovev, & Jackson, 2007; Johnson et al., 2000; Levy et al., 1999; Miller, Muehlenkamp, & Jacobson, 2008; Westen, Dutra, & Shelder, 2005). Among adolescents, BPD is estimated to affect approximately 3% of the general population with higher rates seen in psychiatric populations (i.e., 11% of outpatients and 50% of inpatients; Bernstein et al., 1993; Chanen et al., 2004; 2007; Grilo, Becker, Fehon, & Walker, 1996; Kaess et al., 2013). Further, numerous studies have found associations between BPD symptoms in adolescence and serious psychosocial consequences later in adulthood (Miller, Rathus, & Linehan, 2007; Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006). Accurately diagnosing and treating BPD earlier in the disease course may, therefore, help to prevent maladaptive behavior patterns from becoming ingrained and intractable to treatment later in life.

In addition, youth with BPD have high rates of comorbid psychopathology, reporting an average of three additional diagnoses (Chanen et al., 2007; Kaess et al., 2013). Mood and anxiety disorders are the most common comorbidities. However, substance use disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are also common and predict worse outcomes and reduced likelihood of remission (Chanen et al., 2007; Zanarini et al., 2004). Given the clinical and public health significance of BPD, identifying effective treatments for adolescents with BPD that target both core features of the disorder and the associated sequelae of common co-occurring disorders is essential.

There is strong support for the effective use of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in treating BPD in adult samples, including numerous randomized control trials (for review see Kliem, Kröger, & Kosfelder, 2010). Subsequently, DBT was adapted for use with adolescents (Rathus & Miller, 2014) with promising initial results (Katz, Cox, Gunasekara, & Miller, 2004; MacPherson, Cheavens, & Fristad, 2013; Rathus & Miller, 2002). Much of the research on DBT’s effectiveness with adolescents, however, has examined outpatient treatment whereas youth with multiple comorbid problems, serious emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors, likely to benefit from DBT, are frequently referred to residential treatment settings (Frensch & Cameron, 2002). To our knowledge, only four studies have examined the effectiveness of DBT for adolescents in residential settings. Despite this limited evidence, results are promising with reductions in overall symptom severity (Beckstead, Lambert, DuBose, & Linehan, 2015; McCredie, Quinn, & Covington, 2017) depression symptom severity (Wasser, Tyler, McIlhaney, Taplin, & Henderson, 2008), and number of inpatient days (Sunseri, 2004). However, the treatment duration assessed in these studies was quite long, ranging from four to 29 months and cannot speak to the effectiveness of residential DBT delivered in shorter time frames. The current study seeks to assess the effectiveness of a residential DBT program delivered in a single month (i.e., 28 days).

Additionally, the pervasiveness of childhood abuse among individuals with BPD is well documented, with 27–81% of adults with BPD reporting some type of childhood abuse (Battle et al., 2004; Bornovalova, Huibregtse, Hicks, Keyes, & McGue, 2013; Martin-Blanco et al., 2014; Ogata et al., 1990; Soloff, Lynch, & Kelly, 2002). The severity of childhood abuse, including the duration and nature of abuse, has been found to positively relate to both the severity of BPD symptoms and level of psychosocial impairment (Bornovalova et al., 2013; Zanarini et al., 2002). Additionally, a history of physical and/or sexual abuse predicted poor outcomes for youth in residential treatment (Connor, Miller, Cunningham, & Melloni, 2002; Embry, Vander Stoep, Evens, Ryan, & Pollock, 2000). Given the high prevalence of abuse among adolescents with BPD, it is critical to consider how experiences of abuse may moderate treatment effectiveness.

Goals of the Current Study

The current study tested the effects of a 1-month, intensive DBT residential program for female youth meeting criteria for BPD, with and without abuse histories. This study is part of a larger research program evaluating the etiology and treatment of adolescents diagnosed with BPD (e.g., Auerbach et al., 2016) and prior efforts within this program reported on rates of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors and the associated effect of childhood abuse (Kaplan et al., 2016). There were two primary goals of the current study: (i) test whether a 1-month residential DBT treatment led to reductions in BPD, depression, general anxious distress, and anxious arousal symptom severity and (ii) determine whether sexual and/or physical abuse moderated 1-month treatment effects.

Method

Procedures

The Partners Institutional Review Board approved study procedures. Participants aged 13–17 years provided written assent, while legal guardians and participants 18 and older gave written consent. Participants were recruited from an intensive, residential DBT program. On the first study visit, which coincided with admission to the program, participants completed clinical interviews assessing Axis I and II disorders and exposure to childhood abuse. Additionally, participants completed self-report questionnaires assessing psychiatric symptom severity, including symptoms of BPD, depression, and anxiety. Participants’ symptoms were then re-evaluated after one month of residential DBT treatment.

Treatment protocols were based on Linehan’s (1993) and Rathus & Miller’s (2014) manuals on Dialectical Behavior Therapy, both of which have substantial empirical support for the treatment of suicidal, self-injuring, and multi-diagnostic individuals (for review see MacPherson et al., 2013). DBT is a principle-driven cognitive behavioral treatment, which integrates change-based strategies characteristic of cognitive behavior therapy with validation and acceptance strategies through the application of dialectical principles and techniques. DBT targets behaviors in a hierarchical order, beginning with suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury, followed by treatment-interfering behaviors (e.g., missing therapy sessions) and behaviors that substantially reduce quality of life (e.g., chronic and severe interpersonal conflict). All patients admitted to the 9-bed residential program were provided intensive skills training and acquisition in all four of the core DBT modules (mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness), as well as Miller and Rathus’ additional adolescent module, Walking the Middle Path. The program also provided all elements of standard DBT, including individual therapy, group skills training, 24-hour skills coaching, and therapist consultation team. The DBT modules are taught didactically during three 50-minute periods each weekday morning in a classroom-based setting with participants exposed in the classroom to every skill or concept once within the four-week program. Component skills of each module are taught daily ensuring exposure to multiple skills from each module each day. As in the Rathus & Miller (2014) model, daily homework is assigned for each didactic group and completed either in an afternoon homework group or independently. Additional DBT homework may also be assigned during individual therapy, which occurs twice a week. As part of DBT, patients are required to maintain a daily diary card, with which they record and monitor self-injurious and suicidal thoughts and behaviors along with treatment interfering and quality of life interfering behaviors, levels of emotional distress, and application of DBT skills. Milieu staff is actively made aware of each patient’s DBT targets and support skills use on the milieu, as well as help in implementing DBT specific behavior plans in the milieu. In the afternoon, participants attend two hour-long agenda-based groups that are designed to target DBT skills generalization and help participants continue to think about and practice ways to integrate DBT skills into their lives. Further discussion on setting goals, exploring values, mastering exposure, expanding the capacity for self-assessment and practicing mindfulness are examples of focus of the afternoon groups. Skills generalization is also encouraged during outings into the surrounding community on weekend days. Families participated in treatment through once weekly family sessions and were invited to attend a weekly parent skills group, as well as provided ongoing access to parent skills phone coaching.

Program therapists consisted of three clinical psychologists, one licensed independent social worker, and two post-doctoral fellows. All participants, regardless of medication status, also met twice a week with a program psychiatrist for symptom and medication management. All individual therapists and psychiatrists had, at minimum, received foundational training in DBT offered by Behavioral Tech, LLC (a subsidiary of the The Linehan Institute, founded by Dr. Marsha Linehan). Treatment team members met twice per week for consultation team in line with requirements for DBT treatment.

Participants

Participants were 53 female patients aged 13 to 20 years (M = 17.00, SD = 1.89) who met full criteria for BPD and were seeking residential DBT treatment. The participants were predominantly White (n = 41, 77.36%) with 13.2% (n = 7) of participants reporting more than one race, 7.5% (n = 4) Asian, and 2% (n = 1) African American. The majority of the sample came from two-parent households (n = 36, 67.92%) and reported family income over $100,000 per year (n = 44, 83.02%). Within the sample, medication use was common with nearly all participants treated with at least one psychotropic medication (n = 51, 96.23%) and the majority (n = 31, 58.49%) reporting use of multiple medication types. Participants reported using the following categories of medication: antidepressants (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; n = 39, 73.58%), atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone; n = 26, 49.06%), mood stabilizers (e.g., lamictal; n = 17, 32.08%), benzodiazepines (e.g., klonopin; n = 6, 11.32%), stimulants (e.g., concerta; n = 7, 13.21%), and Naltrexone (n = 3, 5.66%).

Measures

Clinical Interviews.

Psychiatric disorders were assessed by trained BA-level research assistants, graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows. All interviewers received approximately 50 hours of training (e.g., didactics, mock interviews) with regular clinical recalibration meetings to ensure the reliability of diagnoses across interviewers. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, BPD module (SCID-II; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, & Benjamin, 1994) assessed BPD criteria, and each participant’s primary psychiatrist or psychotherapist corroborated the BPD diagnosis. Comorbid diagnoses were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID; Sheehan et al., 2010). The MINI-KID is a brief, structured interview that has shown good reliability and validity in community (Sheehan et al., 2010) and psychiatric (Auerbach, Millner, Stewart, & Esposito, 2015) adolescent samples.

Symptom Severity.

The severity of participants BPD, depression, and anxiety symptoms were assessed using the same measures at pre-treatment and at the 1-month assessment (i.e., post-treatment). The Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD; Zanarini, Vujanovic, Parachini, Boulanger, Frankenburg, & Hennen, 2003) is a 9-item self-report instrument comprised of questions that capture the nine diagnostic criteria for BPD adapted from the BPD module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV). Participants rate the severity of each criteria over the past 1-week on a scale of 0 to 4. Ratings are summed to create a total score with a range of 0 to 36. Greater total scores indicate greater overall BPD severity. Prior research has assessed adolescent BPD severity using the ZAN-BPD (e.g., Goodyer et al., 2011; Krauch et al., 2018). In the current study, the ZAN-BPD had good internal consistency at pre- (α = .82) and post-treatment (α = .84). The Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item questionnaire assessing depressive symptom severity over the past 2 weeks. Items ranged from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity. The internal consistency of the BDI-II at both assessments was excellent (α = .91 and α = .94, respectively). The Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire (MASQ; Watson & Clark, 1991) measures symptoms that commonly occur in mood and anxiety disorders. The current study included the general distress-anxious symptoms (GD-A; 11 items) and anxious arousal (AA; 17 items) subscales. GD-A items measure general negative affect associated with anxiety (e.g., “Worried a lot about things”, “Felt afraid”), whereas the AA items capture physiological experiences of anxiety like somatic tension and hyperarousal (e.g., “Heart was racing or pounding”, “Startled easily”). All items were rated on 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms. Both subscales of the MASQ related to anxiety symptoms were included as independent indices of symptoms to demonstrate the unique effects of treatment on both negative affect and physiological arousal associated with anxiety-related psychopathology. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha at pre- and post-treatment was .85 and .92 for GD-A and .92 and .93 for AA, indicating good to excellent internal consistency.

Childhood Abuse.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003) is a 25-item questionnaire frequently used in adolescent populations to assess the respondent’s experiences of childhood trauma (e.g., Kaplan et al., 2016; Stewart et al., 2015). The current study only used the 5-item subscales of physical and sexual abuse. Item scores ranged from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). Participants’ scores were then dichotomized using established criteria to indicate the presence versus absence of physical (scores ⩾ 8) and sexual (scores ⩾ 6) abuse (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Internal consistency was excellent for the physical abuse (α = .90) and sexual abuse (α = .95) subscales.

Twenty-five participants (50%) endorsed past physical or sexual abuse on the CTQ-SF, and the remainder (n = 25, 50%)1 reported no history of physical or sexual abuse. The participants with and without a history of abuse did not significantly differ in age (t(48) = −0.15, p = .88), race (χ2 (3, n = 50) = 3.71, p = .30, φ = .27), family income (χ2(3, n = 46) = 2.28, p = .52, φ = .22), or in their use of any medication type (range across types: χ2 (1, n = 50) = 0.40 – 3.31, p = .07 - .53, φ = −.26 - .12). At the post-treatment assessment, three participants (6%) did not provide data, resulting in 23 participants endorsing childhood abuse and 24 within no history of abuse. As prior research with this sample has demonstrated distinct patterns of suicidal thoughts and behaviors related to the type of abuse experienced (Kaplan et al., 2016), participants endorsing childhood abuse were further subdivided into categories based on abuse type. Of the 25 participants who reported childhood abuse, 15 reported experiencing sexual abuse only and 10 reported experiencing both sexual and physical abuse. None of the participants reported experiencing only physical abuse. Thus, for analyses comparing treatment outcomes by abuse history, three categories were used: multiple abuse (participants endorsing both physical and sexual abuse), sexual abuse only, and no abuse.

Data Analytic Plan

All analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.0. Prior research with this sample has previously reported on the longitudinal course of self-injurious and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (see Kaplan et al., 2016), whereas the current study examined symptom change related to BPD, depression, and anxiety.

Two-factor mixed-model ANOVAs tested pre- to post-treatment change in symptoms and whether abuse history moderated the treatment effect. Each model included one within-subjects factor with two levels (i.e., Time: pre- and post-treatment ratings of the severity of each symptom) and one between-subjects factor with three levels (i.e., Abuse Category: multiple abuse, sexual abuse only, and no abuse)2. A mixed-model ANOVA tests both main effects of within- and between-factors on the dependent variable, as well as the interaction between within- and between-factors. Within these models, a main effect of Time suggests an effect of treatment independent of abuse history, whereas a main effect of Abuse Category indicates that abuse is associated with differences in average symptoms levels independent of Time. A significant Time x Abuse Category interaction suggests that symptom change was moderated by a participant’s abuse history.

To determine relative differences between the three abuse categories, significant main effects of abuse were probed post hoc using the Games and Howell procedure to determine which pairs of the three groups’ means differed for each symptom type. The Games and Howell procedure was selected for all post hoc comparisons to accommodate unequal sample sizes in each group, as well as reduce vulnerability to violations of the assumption of homogeneity of variance (Howell, 2010).

Results

Attrition and Missing Data

Two participants (3.77%) did not complete the 1-month treatment program, and thus, are not included in the post-treatment assessment analyses resulting in a final sample of 51 participants. There were no significant differences in either participant age or any symptom severity between participants who terminated treatment prematurely and those who completed the program. We also tested the impact of missing data by comparing participants with data missing on any variable (n = 7) relative to those with complete data (n = 44) on all independent variables. Results from t-tests indicated that participants with missing data did not significantly differ from those with no missing data on any independent variable (ps > .08), suggesting little bias was introduced due to missing data.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables. Participants reported an average of 3.61 (SD = 1.50; range = 1 – 8) co-occurring disorders, consistent with prior research in an adolescent BPD sample (e.g., mean comorbid diagnoses = 3.30; Chanen, et al., 2007). Major depressive disorder was the most common co-occurring disorder with 58% of participants meeting criteria (n = 31) followed by anxiety-related disorders (social anxiety disorder: n = 18; panic disorder: n = 15; and PTSD: n = 13) and substance use disorders (alcohol dependence: n = 13; non-alcohol substance dependence: n = 11).

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations, and Range for Age and Symptom Measures

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | ||||||||

| 2. BPDpre | .03 | - | |||||||

| 3. BPDpost | .06 | .58** | - | ||||||

| 4. Deppre | .20 | .68** | .51** | - | |||||

| 5. Deppost | .10 | .42** | .79** | .62** | - | ||||

| 6. GD-Apre | .07 | .42** | .50** | .49** | .56** | - | |||

| 7. GD-Apost | .04 | .31* | .69** | .51** | .81** | .73** | - | ||

| 8. AApre | -.13 | .49** | .46** | .50** | .44** | .79** | .64** | - | |

| 9. AApost | -.09 | .44** | .72** | .48** | .71** | .67** | .88** | .75** | - |

| Mean | 17.00 | 16.51 | 11.09 | 32.71 | 25.00 | 29.42 | 27.17 | 37.54 | 35.17 |

| SD | 1.89 | 7.81 | 7.20 | 13.40 | 14.92 | 8.38 | 10.98 | 13.88 | 15.23 |

| Range | 13 - | 4.00 - | 2.00 - | 7.00 - | 0.00 - | 11.00 - | 11.00 - | 19.00 - | 17.00 - |

| 20 | 33.00 | 34.00 | 60.00 | 60.00 | 46.00 | 53.00 | 76.00 | 73.23 | |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

Pre- and post-treatment scores are indicated by subscript. BPD = borderline personality disorder symptoms; Dep = depression symptoms; GD-A = general anxious distress symptoms; AA = anxious arousal symptoms.

Chi-square tests were used to compare pre- and post-treatment rates of participants reporting symptoms above and below commonly used cut-offs suggesting clinically meaningful severity. Significant differences in rates of participants meeting clinical cut-offs were found for BPD (χ2(2) = 7.98, p = .02, φ = 0.28) and depression (χ2(1) = 6.63, p = .01, φ = 0.26) symptoms, but not general anxious distress (χ2(1) = 3.30, p = .07, φ = 0.18) 3. For BPD symptoms, 31.4% (n = 16) of participants were above the clinical cut-off at pre-treatment (scores 19 and higher on the ZAN-BPD) compared to 21.6% (n = 11) at post-treatment. For depression symptoms, 62.7% (n = 32) of participants reported depression symptoms in the severe to extreme range (scores of 29 and higher on the BDI-II) at pre-treatment. In contrast, at post-treatment only 37.3% (n = 19) continued to report severe symptoms. Using previously established clinical cut-offs for the general anxious distress subscale of the MASQ (scores of 25 and higher; Schalet, Cook, Chio, & Cella, 2014), 68.6% (n = 35) of participants reported clinically significant anxiety symptoms at pre-treatment. Following the 1-month residential program, 51% (n = 26) continued to report high levels of general distress related to anxiety.

1-Month Treatment Response

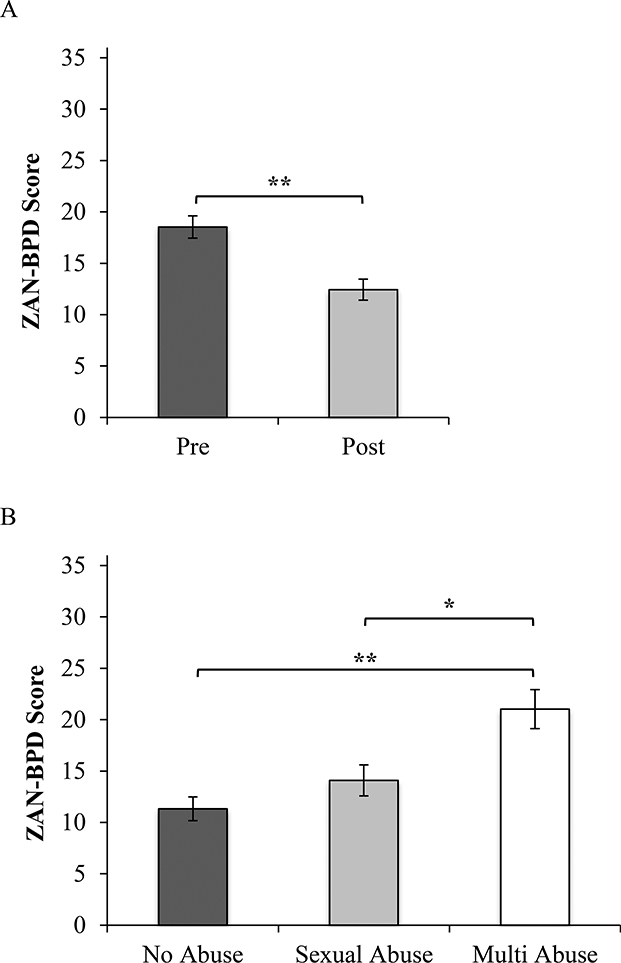

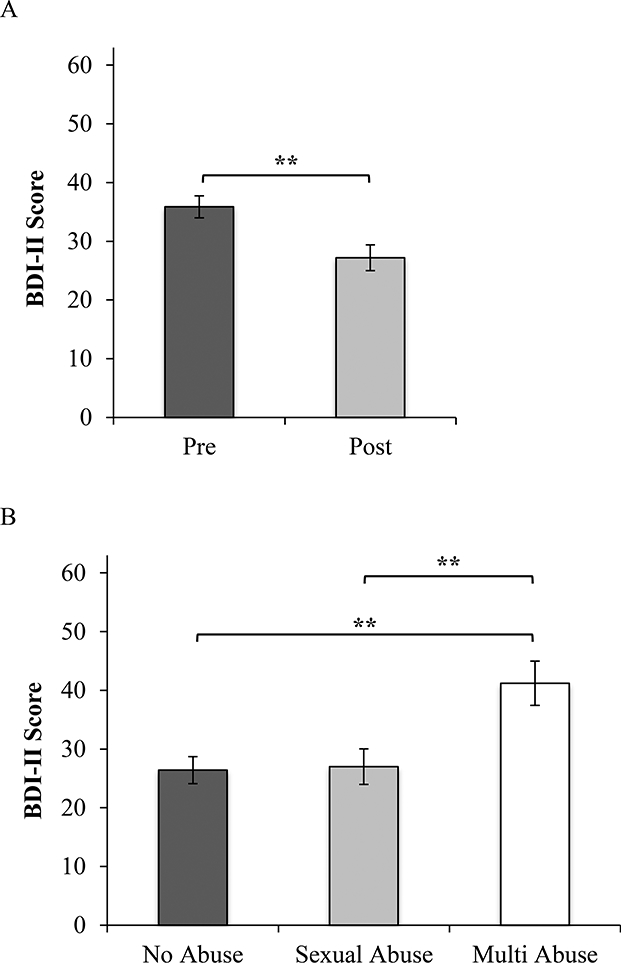

Mixed-model ANOVA was used to test the impact of one month of treatment on each symptom type, as well as whether abuse history moderated treatment effects. A significant main effect for Time emerged for BPD and depression symptoms but not for anxiety symptoms (see Table 2). Specifically, results indicated that symptoms of BPD (Figure 1) and depression (Figure 2) were significantly lower after one month of treatment. In contrast, post-treatment symptoms of general anxious distress and anxious arousal were not significantly different from pre-treatment levels.

Table 2.

Two-factor, Mixed-model ANOVA Comparing Treatment Effect by Abuse Category

| Source | df | SS | MS | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD | ||||||

| Time | 1 | 748.67 | 748.67 | 30.49 | <.001 | .41 |

| Abuse Category | 2 | 1233.24 | 616.62 | 9.56 | <.001 | .30 |

| Time x Abuse Category | 2 | 9.88 | 4.938 | 0.20 | .82 | .01 |

| Errorwithin | 44 | 1080.34 | 24.55 | |||

| Errorbetween | 44 | 2839.57 | 64.54 | |||

| Depression | ||||||

| Time | 1 | 1513.96 | 1513.96 | 19.25 | <.001 | .30 |

| Abuse Category | 2 | 3094.94 | 1547.47 | 6.06 | .01 | .22 |

| Time x Abuse Category | 2 | 32.73 | 16.37 | 0.21 | .81 | .01 |

| Errorwithin | 44 | 3460.81 | 78.66 | |||

| Errorbetween | 44 | 11228.91 | 255.20 | |||

| General Anxious Distress | ||||||

| Time | 1 | 87.44 | 87.44 | 3.39 | .07 | .08 |

| Abuse Category | 2 | 618.76 | 309.38 | 2.09 | .14 | .09 |

| Time x Abuse Category | 2 | 62.70 | 31.35 | 1.21 | .31 | .06 |

| Errorwithin | 42 | 1084.41 | 25.82 | |||

| Errorbetween | 42 | 6212.23 | 147.91 | |||

| Anxious Arousal | ||||||

| Time | 1 | 70.68 | 70.68 | 1.27 | .27 | .03 |

| Abuse Category | 2 | 5089.73 | 2544.86 | 8.96 | .001 | .29 |

| Time x Abuse Category | 2 | 38.04 | 19.02 | 0.34 | .71 | .02 |

| Errorwithin | 44 | 2456.03 | 55.82 | |||

| Errorbetween | 44 | 12500.53 | 284.10 | |||

Note. Time = within subjects effect of treatment, comparing pre to post; Abuse Category = between subjects effect of childhood abuse, comparing no abuse, sexual abuse only, and multiple abuse categories.

Figure 1.

Note. BPD symptoms, assessed with the ZAN-BPD, showed significant reductions from pre- to post-treatment (1A). There was also a significant effect of abuse category on overall symptom severity (1B). Participants with multiple (both physical and sexual) abuse histories showed significantly higher severity than either those with sexual abuse only or no abuse. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

Figure 2.

Note. Depression symptoms, assessed with the BDI-II, showed significant reductions from pre- to post-treatment (1A). There was also a significant effect of abuse category on overall symptom severity (1B). Participants with multiple (both physical and sexual) abuse histories showed significantly higher severity than either those with sexual abuse only or no abuse. ** p < .01, * p < .05.

There was also a main effect of Abuse Category for BPD, depression, and anxious arousal, but not general anxious distress. The significant main effects suggest differences by Abuse Category in the mean of pre- and post-treatment symptom levels (i.e., overall symptom level). As three groups were included in the Abuse Category factor, pairwise comparisons were tested post hoc using the Games and Howell procedure to probe the significant main effect. Results for post-hoc tests are summarized in Table 3. Results indicate that participants who experienced multiple forms of abuse reported significantly higher overall symptoms of BPD, depression, and anxious arousal than participants with either sexual abuse only or no abuse history. There was no significant difference in any of the overall symptoms between the sexual abuse only and the no abuse categories.

Table 3.

Games Howell Post Hoc Comparisons of Mean (Standard Error) Symptom Scores by Abuse Category

| No Abuse n = 24 |

Sexual Abuse Only n = 14 |

Multiple Abuse n = 9 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BPD | 11.32 (1.16)a | 14.09 (1.52)b | 21.03 (1.89)a, b |

| Depression | 26.41 (2.31)c | 27.00 (3.02)d | 41.20 (3.77)c, d |

| General Anxious Distress | 26.87 (1.76) | 26.61 (2.30) | 34.00 (3.25) |

| Anxious Arousal | 33.80 (2.43)e | 31.16 (3.19)f | 51.30 (3.97)e, f |

Note. Superscripts denote significantly differences between group means:

p < .01

p < .05

p < .01

p < .01

p < .05

p < .01

BPD = borderline personality disorder; Multiple Abuse = includes sexual and physical abuse.

Finally, all Time x Abuse Category interactions were non-significant for all symptom types suggesting equivalent effects of treatment regardless of abuse history.

Discussion

The current study evaluated the effectiveness of a brief, though intensive, dose of DBT for adolescents with BPD in a residential treatment setting. After one month of treatment, adolescents reported significant reductions in BPD and depression symptoms with large effects. Two prior studies have assessed full-model DBT in residential settings with similarly promising results. In an American Indian/Alaska Native adolescent sample, Beckstead et al. (2015) found significant reductions in a global measure of clinical distress with 96% of adolescents reaching clinical remission after four months of treatment. After one year of treatment, McCredie et al. (2017) found significant reductions in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptom severity, as well as total number of diagnoses from admission to discharge (McCredie et al., 2017). However, the current study is the first to demonstrate reduction in BPD symptom severity, specifically. Common among these studies was the integration of DBT principles into all aspects of the residential program, including training and consultation for all staff members, DBT skills groups and coaching, and both individual and family DBT sessions. Similar to learning a new language by surrounding oneself with native speakers, this immersive experience may foster faster integration of skills through repeated exposure to DBT constructs resulting in more rapid reductions in symptoms than can be acquired in less comprehensive environments.

Additionally, the current findings are particularly notable given the brevity of the intervention (one month), as prior evaluations of residential DBT programs have evaluated treatment spanning four months to over a year (Beckstead et al., 2015; McCredie et al., 2017; Sunseri, 2004; Wasser et al., 2008). This may suggest an advantage of brief, intensive residential treatment over outpatient approaches, which may require longer durations to achieve similar decreases in symptom severity and, although much lower than non-DBT outpatient treatment, have demonstrated higher drop out rates (e.g., 25% compared to 4% in the current study; Fleischhaker, Böhme, Sixt, Brück, Schneider, & Schulz, 2011). This potential advantage of brief, intensive DBT treatment needs further evaluation to determine if gains are sustained post-treatment and points to an important target for future research.

In contrast, general anxious distress and anxious arousal did not significantly change after one month of treatment. As many adolescents admitted to the residential program engage in high risk and life-threatening behaviors, symptoms of anxiety may have been lower priority to the treatment team and not immediately addressed during the early stages of the program. In the initial phases of treatment, we may even expect awareness of anxiety symptoms to increase as ineffective strategies to avoid emotional distress (e.g., self-harm, suicidal ideation, dissociation) are targeted and mindfulness of emotion is encouraged. It is also possible, however, that anxiety symptoms are not adequately addressed by DBT alone, as prior research in adult samples over longer treatment durations have found mixed and limited reductions in anxiety symptoms (Harned & Valenstein, 2013). These results suggest that targeted anxiety treatments implemented in conjunction with ongoing DBT may be necessary to achieve remission from anxiety related disorders (Harned et al., 2008). Given that individuals with BPD are frequently excluded from clinical trials of anxiety disorders, further research exploring effective strategies for targeting anxiety in this population is warranted (Weertman, Arntz, Schouten, & Dressen, 2005).

Contrary to our hypothesis, a history of child abuse did not moderate treatment effectiveness. This result is hopeful though surprising given prior research demonstrating poorer outcomes for participants with abuse histories (e.g., Connor et al., 2002). The intensity and shorter duration of DBT tested in the current study may reflect a treatment modality that is as effective for adolescents with and without a history of abuse. However, these results may also reflect a limitation of the relatively short duration between assessments in the current study with differential responses to treatment based on abuse history possibly unfolding over longer periods of development or reflected in failures to maintain treatment gains after discharge.

Although relative change in symptoms was similar regardless of abuse history, adolescents who experienced abuse were more likely to demonstrate consistently higher symptom severity. Adolescents who experienced a combination of both sexual and physical abuse were found to have the highest overall symptoms of BPD, depression, and anxious arousal and would, therefore, be less likely to achieve a clinically significant reductions in symptoms. Further, there were no differences in severity of any symptom between participants with no abuse and those reporting a history of sexual abuse only, suggestion a unique added risk for adolescents who have experienced physical abuse in addition to sexual abuse. Prior research has found a similar exposure-response effect with multi-category abuse related to greater decrements in mental health in comparison to single category abuse in adults (Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003) and adolescents (Kaplan et al., 2016). Despite the comparable magnitude of symptom change across treatment, symptom severity is likely to remain in a more acute range at the end of one month for patients who have been exposed to multiple types of abuse. As such, a longer duration of treatment may be warranted for patients who endorse physical and sexual abuse histories, as is the need to incorporate more targeted anxiety treatments in conjunction with standard DBT treatment (Rizvi & Harned, 2013).

Limitations

Results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, there was no treatment comparison or waitlist control group with which to compare outcomes. Second, medication use was common across the sample limiting our ability to attribute treatment effects exclusively to DBT. Third, our sample size was small and demographically homogenous, including only female participants who were primarily White and from families of higher SES. As such, results may not generalize to more diverse populations. Fourth, although all families participated in weekly family meeting, parent participation in optional components of treatment (parent skills group or skills coaching) was not carefully monitored and thus, not accounted for in our final models. Fifth, the assessment of childhood abuse relied exclusively on retrospective recall, which may be vulnerable to reporter bias. Further, none of the participants reported experiencing physical abuse alone, limiting our ability to distinguish effects of distinct forms of abuse. Moreover, our assessment of abuse relied on self-report, and for future research, it would be important to obtain substantiating reports of these events.

Clinical Implications

One-month residential treatment adherent to DBT is effective for reducing symptoms of BPD and depression in adolescents meeting criteria for BPD. In comparison to other studies examining DBT in residential settings over the course of many months to years (MacPherson et al., 2013), we found that a brief, immersive exposure to DBT may be sufficient to stabilize adolescents’ symptoms and return them to less restrictive levels of care.

Although treatment effects were equivalent for adolescents with and without abuse histories, adolescents exposed to multiple types of abuse showed the highest severity of symptoms overall. This may support the need for extending the duration of treatment for abused adolescents to reach equivalent remission of symptoms of BPD and depression as their peers. Additionally, as symptoms of anxiety did not remit for any participants, there is a need for increased focus on anxiety or incorporation of targeted anxiety treatments into ongoing DBT programs. As DBT is a principle, as compared to protocol, driven treatment, targeted treatments to match the needs of specific patients (e.g., PTSD) may be flexibly integrated into treatment, thus allowing providers to attend to co-occurring disorders by targeting common mechanisms within a single treatment (e.g., Rizvi & Harned, 2013). Overall, the results of this study are promising; offering evidence of the association of brief, though intensive, DBT treatment to reductions in symptoms of BPD and depression in adolescents. These results, however, also call for further attention to the integration of anxiety treatment approaches into DBT, which may be particularly needed for patients with multiple abuse histories.

Acknowledgement:

Randy P. Auerbach was partially supported through funding from: National Institute of Mental Health K23MH097786, the Simches Fund, the Rolfe Fund, and the Warner Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or NIMH.

Footnotes

One participant did not complete the CTQ-SF and is missing data on abuse exposure.

Participant age and race were included as covariates in each model, however none were significant and were subsequently dropped from final models for parsimony.

No normed clinical cutoffs have been tested for the MASQ anxious arousal subscale.

References

- Auerbach RP, Millner AJ, Stewart JG, Esposito EC (2015). Identifying differences between depressed adolescent suicide ideators and attempters. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Tarlow N, Bondy E, Stewart JG, Aguirre B, Kaplan C, & Pizzagalli DA (2016). Electrocortical reactivity during self-referential processing in female youth with borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 1(4), 335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle C, Shea M, Johnson D, Yen S, Zlotnick C, Zanarini M, Morey L (2004). Childhood maltreatment associated with adult personality disorders: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(2), 193–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, Grilo CM, Morey LC, et al. (1999). Applicability of personality disorder criteria to hospitalized adolescents: Evaluation of internal consistency and criterion overlap Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead DJ, Lambert MJ, DuBose AP, & Linehan M (2015). Dialectical Behavior Therapy with American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents diagnosed with substance use disorders: Combining an evidence based treatment with cultural, traditional, and spiritual beliefs. Addictive Behaviors, 51, 84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, & Shinsato L (1993). Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1237–1243. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, & Fink L (1998). Manual for the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova M, Huibregtse B, Hicks B, Keyes M, McGue M, Iacono W, & Goodman Sherryl. (2013). Tests of a Direct Effect of Childhood Abuse on Adult Borderline Personality Disorder Traits: A Longitudinal Discordant Twin Design. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 180–194. doi: 10.1037/a0028328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen A, Jackson H, Mcgorry P, Allot K, Clarkson V, & Yuen H (2004). Two-year stability of personality disorder in older adolescent outpatients. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(6), 526–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jovev M, & Jackson HJ (2007). Adaptive functioning and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68, 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor D, Miller K, Cunningham J, & Melloni R (2002). What does getting better mean? Child improvement and measure of outcome in residential treatment. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72(1), 110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, & Anda RF (2003). Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1453–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embry LE, Vander Stoep A, Evens C, Ryan KD, & Pollock A (2000). Risk factors for homelessness in adolescents released from psychiatric residential treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1293–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Benjamin L (1994). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II, version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhaker C, Böhme R, Sixt B, Brück C, Schneider C, & Schulz E (2011). Dialectical Behavioral Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A): A clinical trial for patients with suicidal and self-injurious behavior and borderline symptoms with a one-year follow-up. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5, 3. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-5-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frensch K, & Cameron M (2002). Treatment of choice or a last resort? A review of residential mental health placements for children and youth. Child and Youth Care Forum, 31(5), 307–339. doi: 10.1023/A:1016826627406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Tsancheva S, Byford S, Dubicka B, Hill J, Kelvin R Fonagy P. (2011). Improving mood with psychoanalytic and cognitive therapies (IMPACT): A pragmatic effectiveness superiority trial to investigate whether specialized psychological treatment reduces the risk for relapse in adolescents with moderate to severe unipolar depression: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 12, 1–12. doi.org/ 10.1186/1745-6215-12-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo C, Becker D, Fehon D, & Walker M (1996). Gender differences in personality disorders in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(8), 1089–91. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS, Chapman AL, Dexter-Mazza ET, Murray A, Comtois KA, & Linehan MM (2008). Treating co-occurring Axis I disorders in recurrently suicidal women with borderline personality disorder: A 2-year randomized trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy versus community treatment by experts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 1068–1075. doi: 10.1037/a0014044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS, & Valenstein HR (2013). Treatment of borderline personality disorder and co-occurring anxiety disorders. F1000Prime Reports, 5, 15. doi: 10.12703/P5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell DC (2010). Statistical methods for psychology (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol A, Hamagami F, & Brook J (2000). Age‐related change in personality disorder trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood: A community‐based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(4), 265–275. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaess M, Von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna I, Parzer P, Chanen A, Mundt C, Resch F, & Brunner R (2013). Axis I and II comorbidity and psychosocial functioning in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology, 46, 55–62. doi: 10.1159/000338715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan C, Tarlow N, Stewart J, Aguirre B, Galen G, & Auerbach RP (2016). Borderline personality disorder in youth: The prospective impact of child abuse on non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 71, 86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LY, Cox BJ, Gunasekara S, & Miller AL (2004). Feasibility of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for suicidal adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(3), 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliem S, Kröger C, & Kosfelder J (2010). Dialectical Behavior Therapy for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 936–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauch M, Ueltzhoffer K, Brunner R, Kaess M, Hensel S, Herpertz SC, & Bertsch K (2018). Heightened salience of anger and aggression in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder – A script-based fMRI study. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 1–11. doi.org/ 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy K, Becker D, Grilo C, Mattanah J, Garnet K, Quinlan D, Mcglashan T (1999). Concurrent and predictive validity of the personality disorder diagnosis in adolescent inpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry,156(10), 1522–1528. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson HA, Cheavens JS, & Fristad MA (2013). Dialectical Behavior Therapy for adolescents: Theory, treatment adaptations, and empirical outcomes. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(1), 59–80. doi: 10.1007/s10567-012-0126-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Blanco A, Soler J, Villalta L, Feliu-Soler A, Elices M, Pérez V, Pascual JC (2014). Exploring the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits on the severity of borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry,55, 311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCredie M, Quinn C, & Covington M (2017). Dialectical Behavior Therapy in adolescent residential treatment: Outcomes and effectiveness. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 34(2), 84–106. doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2016.1271291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Muehlenkamp JJ, & Jacobson CM (2008). Fact or fiction: Diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, & Linehan MM (2007). Dialectical Behavior Therapy with Suicidal Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E & Prinstein MJ (2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144(1), 65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, & Hill EM (1990). Childhood sexual and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1008–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathus JH, Miller AL (2014). DBT Skills Manual for Adolescents. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rathus JH, & Miller AL (2002). Dialectical Behavior Therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32, 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi S, & Harned M (2013). Increasing treatment efficiency and effectiveness: Rethinking approaches to assessing and treating comorbid disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(3), 285–290. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schalet BD, Cook KF, Choi SW, & Cella D (2014). Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety: Linking the MASQ, PANAS, and GAD-7 to PROMIS Anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(1), 88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, et al. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Lynch KG, & Kelly TM (2002). Childhood abuse as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 16, 201–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JG, Kim JC, Esposito EC, Gold J, Nock MK, & Auerbach RP (2015). Predicting suicide attempts in depressed adolescents: Clarifying the role of disinhibition and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of affective disorders, 187, 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunseri PA (2004). Preliminary outcomes on the use of Dialectical Behavior Therapy to reduce hospitalization among adolescents in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 21, 59–76. doi: 10.1300/J007v21n04_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wasser T, Tyler R, Mcllhaney K, Taplin R, & Henderson L (2008). Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) versus Standard Therapeutic Milieu (STM) in a cohort of adolescents receiving residential treatment. Best Practices in Mental Health: An International Journal, 4, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1991). The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire Unpublished manuscript, University of Iowa, Department of Psychology, Iowa City. [Google Scholar]

- Weertman A, Arntz A, Schouten E, & Dreessen L (2005). Influences of beliefs and personality disorders on treatment outcome in anxiety patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 936–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Dutra L, & Shedler J (2005). Assessing adolescent personality pathology. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini M, Frankenburg F, Vujanovic A, Hennen J, Reich D, & Silk K (2004). Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder: Description of 6‐year course and prediction to time‐to‐remission. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110(6), 416–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00362.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J (2003) Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): A continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini M, Yong L, Frankenburg F, Hennen J, Reich D, Marino M, & Vujanovic A (2002). Severity of reported childhood sexual abuse and its relationship to severity of borderline psychopathology and psychosocial impairment among borderline inpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(6), 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]