Abstract

Recent studies revealed that cellular prion protein on neurons bind Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta oligomers causing neurotoxic effects. A new article in Cell Reports by Gunther and colleagues shows that an orally administered cellular prion protein antagonist can rescue synaptic and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s mice overexpressing amyloid-beta.

Keywords: Cellular prion protein, Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid-beta oligomers, Antagonist, Cognition

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, characterized by neurovascular dysfunction, accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) in brain parenchyma and vasculature, tau pathology, and neuronal loss [1]. Prions are misfolded proteins that have been implicated in several diseases including transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome, and recently in AD [2–4]. The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is a small, cell-surface glycoprotein that has several physiological functions in brain. For example, PrPC protects against neuronal stress (e.g., apoptosis, oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress), maintains myelin, modulates neuronal excitability, and can induce neurite outgrowth and extension [5]. Importantly, PrPC is one of the cellular receptors for oligomeric form of Aβ (Aβo) [2,3]. Previous studies have shown that PrPC and Aβo interaction on neurons leads to neuronal dysfunction, suppression of synaptic plasticity and cognitive impairment [6]. It has been also shown that blocking PrPC-Aβo interactions with peripherally-administered antibodies improves learning and memory in mouse models of amyloidosis [2,7]. Here, we highlight a recent study by Gunther et al. demonstrating that an orally administered PrPC antagonist rescues synaptic and behavioral deficits in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mouse model of Aβ amyloidosis [8], suggesting its potential therapeutic implications for AD.

In search for a novel PrPC antagonist, Gunther et al. screened 2,560 known drugs and 10,130 diverse small molecules for inhibition of PrPC interaction with Aβ1–42 oligomers [8]. The screen initially identified a promising cephalosporin antibiotic, cefixime, but further validation suggested that the inhibitory action may result from a cephalosporin degradation product. The authors then screened cephalosporin degradation products and discovered conditions under which ceftazidime degradation resulted in an active antagonist termed compound Z [8]. Compound Z not only disrupted the interaction between PrPC and Aβ1–42 oligomers but also mitigated behavioral deficits in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice when administrated centrally into the brain [8]. While compound Z was effective in reducing cognitive dysfunction, it did not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which limits its therapeutic potential.

To overcome the BBB hurdle, the authors employed a directed approach for inhibitor development with insight from compound Z’s chemical nature and sought to identify molecules with greater potential to cross the BBB. A range of negatively-charged polymers were identified with specific PrPC affinity in the low to sub-nanomolar range, from both biological (melanin) and synthetic (Poly (4-styrenesulfonic acid-co-maleic acid), PSCMA) origins [8]. They identified that polystyrene sulfonate and PSCMA, like compound Z, function to provide potent inhibition of Aβo binding and protection of dendritic spines from Aβo-induced loss [8]. When delivered orally, PSCMA (20 kDa) can cross the BBB and functions to inhibit PrPC binding to Aβo in vivo as shown in 12-month old APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice with established Aβ plaque accumulation, synaptic loss and learning and memory deficits. In these mice, PSCMA rescued learning and memory on Morris water maze behavior test. It also repaired synaptic loss as shown by increased expression of presynaptic anti-synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A in hippocampus, but did not alter Aβ metabolism or gliosis [8]. A previous study showed that Aβo-induced PrPC activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor-5 (mGluR5) co-receptors and downstream signaling through Fyn-kinase phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR2B and tau leads to synaptic dysfunction [3]. Whether PSCMA can alter function of other synaptic molecules is presently unknown. Future studies should investigate in greater depth the impact of PSCMA on key synaptic players by electrophysiological, pharmacological and molecular analysis in other mouse models of amyloidosis and AD.

In addition to neurons, PrPC is also expressed by brain endothelial cells, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [5]). This raises the question what is the cellular specificity and/or differential functions of compound Z and PSCMA binding to PrPC on different cell types in the brain, and could this contribute to the observed improvements in cognition? There are many “good” and “bad” receptors and soluble carrier proteins that can bind Aβo and either regulate Aβo clearance and degradation or initiate and promote Aβo toxicity [3]. An example of a “good” receptor is the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) [3]. LRP1 is expressed by several cell types, but at the BBB endothelium LRP1 functions as a major clearance receptor for Aβ [1] and mediates PrPC-bound Aβ clearance from brain-to-blood [9]. An example of a “bad” receptor is the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) at the luminal side of BBB endothelium that mediates entry of Aβ from blood-to-brain [1,3]. Studies have shown that preventing Aβ-RAGE interaction blocks Aβo-mediated deficits in synaptic strength [1]. Whether compound Z and PSCMA can impact Aβ clearance from the brain across the BBB by blocking PrPc remains unknown.

Interestingly, PrPC also exists in soluble form in the brain and competes with membrane-anchored PrPC for binding Aβo. Soluble PrPC was recently reported to bind Aβo and thereby delay fibril formation [10]. Recent studies revealed the ability of Aβo from cadaveric pituitary growth hormone to seed and promote the formation of Aβ plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy [11]. Do compound Z and PSCMA interact and alter functions of soluble PrPC and could this affect Aβ seeding and fibril formation remains elusive.

In summary, the new study by Gunther et al. [8], along with other previous publications, strengthens the idea that interfering with the binding of Aβo to PrPC on neurons could mitigate AD-associated memory loss (see Figure 1). The efficacy of PrPC antagonists in amyloidosis models should be confirmed, however, by additional studies, since PrPC-Aβo interactions are differentially affected in different models of amyloidosis, as recently reported [12]. This raises a question whether binding efficiency of PrPC antagonists varies between different Aβo species and/or if binding is influenced by other receptors or carriers in the vicinity of PrPC. Nevertheless, this exciting new work has promising therapeutic implications for AD, but the translational potential in humans remains to be seen.

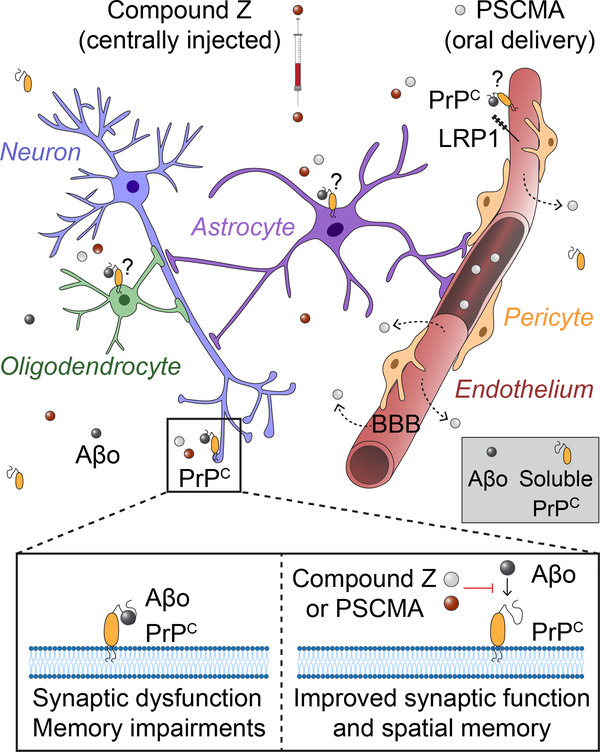

Figure 1. PrPC antagonists improve synaptic function and spatial memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease.

Binding of amyloid-β oligomers (Aβo, black circles) to neuronal cellular prion protein (PrPC) leads to synaptic dysfunction and memory impairments. Centrally administered compound Z (red circles) and orally delivered Poly (4-styrenesulfonic acid-co-maleic acid) (PSCMA) that crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (gray circles), both inhibit Aβo binding to PrPC on neurons (blue). This improves synaptic function and spatial memory deficit in Alzheimer’s mouse model of β-amyloidosis. Endothelial cells (red), astrocytes (purple) and oligodendrocytes (green) also express PrPC. Whether inhibiting PrPC-Aβo interactions on non-neuronal cell types can affect their function and/or contribute to the observed beneficial effects of compound Z or PSCMA, remains presently unclear. For example, whether compound Z or PSCMA can impact low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1)-mediated clearance of PrPC-bound Aβ across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is currently unknown. Do compound Z and PSCMA interact and alter functions of soluble PrPC interaction with Aβo which can affect fibril formation (gray box) remains elusive.

Acknowledgements

The work of B.V.Z. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant nos. R01AG023084, R01NS090904, R01NS034467, R01AG039452, 1R01NS100459, 5P01AG052350, and 5P50AG005142 in addition to the Alzheimer’s Association grant no. 509279, Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, and the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence for the Study of Perivascular Spaces in Small Vessel Disease reference no. 16 CVD 05. The work of A.R.N. is supported by NIH grant no. K99AG058780.

References

- 1.Sweeney MD et al. (2019) Blood-Brain Barrier: From Physiology to Disease and Back. Physiol. Rev 99, 21–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purro SA et al. (2018) Prion Protein as a Toxic Acceptor of Amyloid-β Oligomers. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 358–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarosz-Griffiths HH et al. (2016) Amyloid-β Receptors: The Good, the Bad, and the Prion Protein. J. Biol. Chem 291, 3174–3183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colby DW and Prusiner SB (2011) Prions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3, a006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle AR and Gill AC (2017) Physiological Functions of the Cellular Prion Protein. Front Mol Biosci 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurén J et al. (2009) Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature 457, 1128–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung E et al. (2010) Anti-PrPC monoclonal antibody infusion as a novel treatment for cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model mouse. BMC Neurosci 11, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunther EC et al. (2019) Rescue of Transgenic Alzheimer’s Pathophysiology by Polymeric Cellular Prion Protein Antagonists. Cell Rep [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pflanzner T et al. (2012) Cellular prion protein participates in amyloid-β transcytosis across the blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 32, 628–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagano K et al. (2018) Effects of Prion Protein on Aβ42 and Pyroglutamate-Modified AβpΕ3–42 Oligomerization and Toxicity. Mol. Neurobiol DOI: 10.1007/s12035-018-1202-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purro SA et al. (2018) Transmission of amyloid-β protein pathology from cadaveric pituitary growth hormone. Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0790-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kostylev MA et al. (2015) Prion-Protein-interacting Amyloid-β Oligomers of High Molecular Weight Are Tightly Correlated with Memory Impairment in Multiple Alzheimer Mouse Models. J. Biol. Chem 290, 17415–17438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]