Abstract

Background:

Cancer affects both men and women, yet systematic understanding of the role of gender in caregiving and dyadic caregiver-patient interactions is lacking. Thus, it may be useful to review how gender theories apply to cancer caregiving, and to evaluate the adequacy of current cancer caregiving studies to the gender theories.

Methods:

Several databases, including MEDLINE (Ovid), PsychINFO, PubMed, and CINAHL, were used for searching articles published in English between 2000 and 2016. The search was restricted by age (≥ 18), and yielded 602 articles, which were subject to further screen and review based on selection criteria. Of 108 full texts reviewed to determine inclusion eligibility for this review, 55 met the criteria and included for review.

Results:

The reviewed studies supported the “gender role” and “doing gender” perspectives for caregiver selection. The role identity, role strain, and transactional stress theories were supported for predicting caregiving outcomes at the individual level. Furthermore, attachment, self-determination, and interdependence theories incorporated caregiver factors that predicted the patients’ outcomes, and vice versa.

Conclusion:

Despite limited gender theory-driven research in cancer caregiving and psycho-oncology in general, the utility of gender theories in (a) identifying sub-groups of caregiver-patient dyads who are vulnerable to the adverse effects of cancer in the family and (b) developing evidence-based interventions is promising. Integrating broader issues of medical trajectory, lifespan, sociocultural, and biological factors in gender-oriented research and practice in Psycho-Oncology is encouraged.

Keywords: gender/sex, gender theories, caregiving processes and outcomes, psychological distress, cancer, oncology

Over the past few decades, the gender composition of family caregivers who provide unpaid informal care to persons with medical illness has changed noticeably: male caregivers (of all kinds) were 25% of the caregivers surveyed in 1987 and were 40% in 2016.1 Inasmuch as caregiving has historically been considered a women’s role, contemporary caregiving research must reflect this changing representation to better understand the role of gender in various aspects of caregiving.2

The number of persons diagnosed with cancer has continued to increase. So does the number of their family caregivers who provide an extremely important source of care for cancer patients and survivors.3 Gender issues in caregiving have been theorized, although primarily grounded on caregiving to patients with dementia.2 Cancer caregiving is more acute yet intense compared with caregiving for patients with other chronic illness.4 Thus, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about cancer caregiving from studies of other diseases. In this article, we present several theories that predict caregiving involvement and outcomes by gender of the caregiver or the patient, as a conceptual guide to evaluate their utility in current cancer caregiving studies. The selected theories are traditional gender theories and relational theories, which have been applied to examine gender similarities and differences in caregiving in psychological science.

Gender Theories on Involvement in Caregiving

The gender-role perspective posits that individuals learn what are generally considered appropriate or desirable roles to enact in social relations, often defined by norms of society centered around concepts of femininity and masculinity. A common stereotype of female gender relates to nurturing behaviors; when family members or others in society are in need of care, females who perceive themselves as societal members expected to provide care are more likely to do so.5 Also, females who have been reinforced for their nurturing behaviors are more likely to carry them out in the future, according to the gender-role socialization view. Thus, in this view, women engage in caregiving behaviors largely due to social developmental and learning processes, whereas caregiving signifies for men a new, unexpected role.5 Clearly roles are fluid over time, as a product of diverse social forces. However, these characterizations are widely accepted as remaining largely applicable in a general gender-role model.

Other recent gender theories have different perspectives.6 For example, a gender relations approach considers gender to be a system of stratification simultaneously signifying power and structural interactions between and among men and women. A “doing gender” approach7 emphasizes that a gendered self emerges by enacting internalized ideals of behaviors formed by interpersonal interactions. The crux of this approach is that behavior is not determined by individuals’ gender identity but by relational and institutional contexts in which the individuals enact gendered selves and sexual identities. While people orient their behaviors to gender ideals, behavior itself can vary by context (e.g., the context of the caregiver-patient dyad).7

Another viewpoint, the lifespan perspective, incorporates late-life role changes due to retirement, the empty-nest experience, etc. Late-life role changes result in differential shifting of psychological and social behavior by gender: men toward nurturing others, women toward productivity and assertiveness.8 Thus, in later life, men’s caregiving role can be more welcome and associated with greater feelings of self-efficacy and mastery, whereas women’s caregiving role can be associated with constraint and resentment. Natural biological changes related to aging in women and men may also influence caregiving perceptions and behaviors.

Yet another view, the close-relationship research perspective, emphasizes emotional closeness as a determinant of caregiver selection, as the inherent nature of caregiving or care receiving involves an intimate emotional tie between the two.9 According to this perspective, females often become primary caregivers because they are more emotionally connected to the patient than men, more inclined to sacrifice their social life, and to ask for little help from others, even if others are available, in order to maintain emotional closeness with the patient.9

Individual-Oriented Gender Theories on Caregiving Experiences and Consequences

A second issue is who is more or less likely suffer from caregiving, and why. Again, there are several perspectives on this question. Two early meta-analyses10, 11 concluded that caregivers’ gender differences in mental and physical health outcomes exist because females deal with more stressful caregiving cases and situations, yet have fewer social resources, compared to males. The transactional stress theory of Lazarus and Folkman12 and its descendants, such as the Pearlin Stress Process Model and the Modified Stress Process Model,13 are commonly employed theoretical framework explaining such differential outcomes of caregiving experiences at the invidivual level. This framework posits that when a demand, either internal or external, is appraised as exceeding the person’s resources, the demand constitutes a stressor.

Guided mainly by this conceptual framework, a meta-analysis2 on caregiver stressors, social resources, and physical health found that compared to men, women provided more caregiving hours, helped with more caregiving tasks, and assisted with more personal care. Women also reported higher levels of caregiving burden and depression, and lower levels of subjective well-being and physical health. When gender differences in stressors (e.g., hours of caregiving) and resources (e.g., social support) were controlled for, however, the size of gender differences in depression and physical health reduced to levels observed in non-caregiving samples.

Role identity theory5 provides another commonly employed view on caregiver burden, by positing that the more the caregiver role is embraced, the less the caregiver is burdened by that role. Specifically, caregiver identity theory posits that individuals undergo self-appraisal through their new caregiver role and determine to what extent the role is congruent with their global self-identity. When the two identities are incongruent, distress arises. Increased caregiving demands often aggravate role discrepancies, resulting in more severe negative outcomes. Grounded on this theory, males may experience more distress when required to take on tasks incongruent with their gender identity. However, male caregivers tend to show lower levels of stress, which researchers have attributed to their acceptance of their caregiving as a challenge in which they focus on necessary tasks while ignoring emotions.14

A new caregiver role on top of existing social roles can be associated with different outcomes. According to the role strain theory,15 caregiver and work responsibilities frequently compete and conflict when individuals struggle to meet demands from multiple competing roles. This is particularly common for middle-aged persons of the so-called “sandwich generation,” who have responsibilities for the generations on either side of them: older and younger. Thus, female and adult-child caregivers are more likely to have negative caregiving outcomes, as they are often involved in several social roles including caregiving and at work. A fast growing caregiver population, grandparents who provide care for their grandchildren, are also more likely to become unemployed than their non-caregiving counterpart to accommodate additional strains from caregiving.

Role enhancement theory,15 on the other hand, posits that performing multiple roles can have positive consequences, as participating in additional roles provides the person with more opportunities and resources to build social skills and improve self-esteem. Accordingly, persons with additional roles, such as employed caregivers as opposed to non-employed caregivers, are more likely to function better in performing the target caregiver role.

Relationship-Oriented Gender Theories on Caregiving Experiences and Consequences

Not all gender theories take the individual as the dominant perspective. Some theories focus instead on the nature of the relationships between caregiver and patient. According to the social exchange theory perspective, caregivers who are in less mutual and more unilateral relationships with the care recipient (by doing more work and receiving fewer rewards) would be expected to experience greater burden.16 However, among family caregivers, such under-benefited relationships of giving more than receiving can be functional, under the expectation that the balance of exchange would be reestablished in the future and by feelings of indebtedness to care-recipients, particularly for parents for all that they have done in the past.17

Adult attachment theory18 provides useful guidance for conceptualizing gender in caregiving for relatives with medical illness from an interpersonal and family context. This theory posits that humans have an attachment system operating to maintain a sense of security, which is activated by threat. Individual differences in attachment patterns arise because attachment figures vary in responsiveness in times of need. Similarly, individual differences in caregiving behavior in response to a partner’s distress exist.13, 19 For example, secure attachment is likely to be tied to sensitive and cooperative caregiving in response to situational stresses, whereas avoidant attachment is likely to be related to less involvement in caregiving and to poorer caregiving when there is need for emotional support. Anxious attachment, on the other hand, is likely to be related to compulsive and controlling caregiving, driven and dominating rather than responsive and cooperative, which often becomes ineffective caregiving.

Another relationship-oriented theory useful for conceptualizing gender in caregiving for relatives with medical illness is self-determination theory.20 According to this theory, there are diverse reasons to engage in any particular behavior. These regulatory motives can be ordered along a continuum ranging from controlled to autonomous. The most controlled motive for acting is external, in which a behavior is engaged in because of external forces such as rewards or punishments. When the motive has begun to be internalized but regulation of the behavior is dependent upon implicit self-approval for compliance and self-derogation for noncompliance, the motive is introjected. The next step is an identified motive, where a member of a group or society fully accepts and thus volitionally engages in behaviors that are valued by that collective. With respect to caregiving, this would mean that the value of caring for an ill spouse is held by one’s community and one personally believes the value is worthy in its own right. In the next most autonomous form of motivation, the person integrates this societal value with other aspects of the self. This integrated motive involves loving and respecting the care recipient as well as acknowledging that caregiving provides meaning and purpose.20

Interdependence theory on close relationships17 is particularly important for understanding the role of gender in the interpersonal context, as two meta-analyses found that cancer patients and their caregivers report moderately correlated levels of psychological distress, regardless of the patient’s gender.21, 22 These findings suggest that cancer has a similar psychological impact on both patients and caregivers, and that there is concordance in their emotional well-being. The findings also reinforce the importance of gaining better scientific understanding of how women and men emotionally influence each other while under stress.

Present Review Project

The theories presented above provide a comprehensive framework to better understand and predict who is likely to be involved in caregiving for relatives with cancer and how gender of the caregiver and the patient would influence caregiving outcomes with cancer caregiver population. Despite the acknowledgement of the significant role of gender in psycho-oncology,23 only a few studies to date, have tested any gender theories with a cancer caregiver population. Thus, we reviewed publications on cancer caregiving and considered the adequacy of gender theories to those studies. We hypothesized that as cancer diagnosis often comes as a surprise, the initial involvement in cancer caregiving may be less likely to be determined solely by the caregivers’ gender than for other diseases and may be more likely to be determined based on proximity and availability (caregiving involvement hypothesis).

Regarding caregiving outcomes, we hypothesized that role theories and transaction stress theory and its descendants would be mainly supported by those who feel pressured to carry out the caregiver role and those who have fewer resources to adjust to the new caregiver role. This would be reflected in reporting greater ill-being outcomes (individual-level caregiving outcome hypothesis). We also hypothesized that interdependence theory would be mainly supported for relational-level caregiving outcomes (relational-level caregiving outcome hypothesis).

Methods

We searched the several databases, including MEDLINE (Ovid), PsychINFO, PubMed, and CINAHL, for articles published in English between 2000 and 2016. Keywords searched included target population (caregiver, daughter, famil*, husband, son, spouse, and wife), target of interest (cancer/neoplasm, caregiving, gender, sex, and oncology), and target outcomes (illness adjustment, mental health/functioning/morbidity, physical health/functioning/morbidity, psychological adaptation, psychosocial, quality of life, spiritual adjustment, and well-being). The search restricted by age (≥ 18) yielded 602 articles.

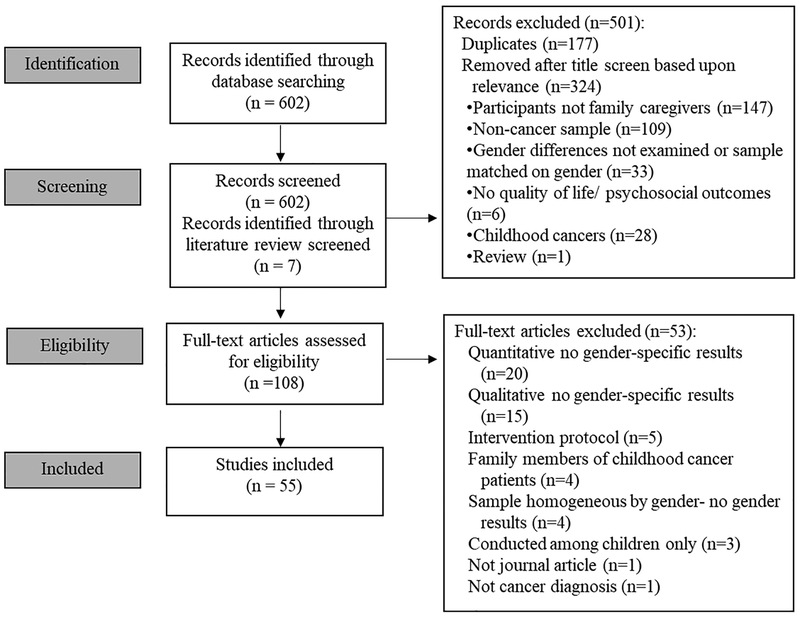

As shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1), titles and abstracts of the studies were screened and reviewed using the following selection criteria: Data-based research articles, published in refereed journals, which utilized rigorous quantitative or qualitative methods, had a representative sample with a sufficient sample size to address the research questions, and used validated measures. We excluded studies of family members of pediatric cancer patients, due to the substantial differences in treatment and concerns involved and the nature of gender in the caregiver-patient dyads, compared with adult cancer patients.

Figure 1:

PRISMA flowchart

Of 602, we excluded 177 duplicates and 324 articles after title screen based on relevance (e.g., 147 articles on non-family or friend caregivers; 109 artciles on non-cancer sample), Including seven studies that were not identified through the search criteria we used but were found from a recent literature review,24 a total of 108 full text articles were subject to further review. Of 108, articles reporting no gender specific results (35), intervention protocol (5), pediatric patients’ family members (4), no gender results due to the sample was homogeneous by gender (4), pediatric patients (3), not a journal article (1), and not cancer patients (1) were excluded, yielding 55 studies to be included in this review.

Results

As shown in Table 1, studies reviewed are organized by caregiver selection, caregiving outcomes at the individual level, and caregiving outcomes at the relational level or context.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and gender findings

| Study | Caregiver Characteristics | Patient Characteristics | Gender Findings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Caregiver Selection | ||||||||

| Ref # | Authors | Year | % Female (Sample Size) | Caregiver Demographics | % Female (Sample Size) | Patient Demographics | Results | Supporting Theories |

| Study Design | ||||||||

| 19 | Luszczynska et al. | 2007 | 62.4% (224) |

Mean age (SD):

59.4 (9.6) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-German sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

37.6% (173) |

Mean age (SD):

61.9 (8.5) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-German sample Diagnosis: 27.1% Colorectal, 12.3% Stomach, 10.4% Liver/Gallbladder, 7.5% Lung/Bronchi, 22.6% Other Stage: 22.5% I, 22.5% II, 27.5% III, 27.5% IV |

|

“Doing Gender”; Gender Role Perspective; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 25 | Lopez et al. | 2012 | 0% (15) |

Mean age (SD): 60 (13) Race/Ethnicity: 100% White/Caucasian Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

100% (15) |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 67% Gynecologic, 33% Breast Stage: Not reported |

|

“Doing Gender”; Role Identity Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Qualitative | ||||||||

| 26 | Ussher et al. | 2013 | 64.2% (53) |

Mean age: 56 Race/Ethnicity: 96% Caucasian, 4% Asian Relationship to patient: 77% Partner, 8% Parent, 6% Friend, 4% Child, 4% Sibling |

Not reported |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 25% Breast, 14% Brain, 14% Respiratory, 12% Colorectal, 12% Prostate, 23% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity theory; Role Strain Theory; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Qualitative | ||||||||

| 27 | Segrin et al. | 2010 | 54.4% (215) |

Mean age (SD):

52.7 (13.3) Race/Ethnicity: 68.1% White, 28.1% Latino/a, Relationship to patient: 71.2% Spouse, 5.1% Sibling, 4.7% Parent, 11.9% Other |

67.4% (215) |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 67.4% breast, 32.6% prostate Stage: 34% I, 42% II, 18% III |

|

“Doing Gender”; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 28 | Kim & Carver | 2007 | 51.9% (400) |

Mean age (SD):

55.7 (10.9) Race/Ethnicity: 91.5% Caucasian Relationship to patient: 65% Spouse |

47.9% (Not reported) |

Mean age (SD):

55.5 (11.0) Race/Ethnicity: 95% Caucasian Diagnosis: 25% Prostate, 23% Breast, 13% Colorectal, 30% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Attachment theory; Gender Role Perspective; |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 29 | Oliffe et al. | 2015 | 100% (15) |

Mean age (SD): 66 Race/Ethnicity: 100% Canadian/European Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

0% (15) |

Mean age (SD): 72 Race/Ethnicity: 100% Canadian/European Diagnosis: 100% Prostate Stage: Not reported |

|

Gender Role Perspective. |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Qualitative | ||||||||

| 30 | Perz et al. | 2011 | 67.3% (329) |

Mean age (SD):

54.8 (13.0) Race/Ethnicity: 81.6% Australian/White European, 4.0% Asian, 14.4% unknown Relationship to patient: 73.3% Partner, 11.2% Child, 7.5% Parent, 2.9% Sibling, 2.7% Friend, 2.4% Other |

67.3% (369) |

Mean age (SD):

58.8 (13.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 13.9% Breast, 11.5% GI, 7.4% Hematological, 6.0% Prostate, 5.6% Gynecological, 27.6% Other, 27.9% Missing Stage: 11.4% I-II, 5.1% III-IV, 19.1% Unknown, 18.3% Unstaged |

|

Gender Role Perspective; Role Strain Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 31 | Kim et al. | 2008b | 50.6% (168) |

Mean age (SD):

59.7 (9.8) Race/Ethnicity: 95.2% White/Caucasian Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

49.4% (168) |

Mean age (SD):

60.2 (10.2) Race/Ethnicity: 90.5% Caucasian Diagnosis: 49.4% Breast, 50.6% Prostate Stage: Not reported |

|

Gender Role Perspective; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 32 | Jenewein | 2008 | 100% (31) |

Mean age (SD):

55.4 (10.8) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

0% (31) |

Mean age (SD):

58.2 (10.1) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss Sample Diagnosis: 100% Oral Stage: 54.8% I-II, 45.2% III-IV |

|

Gender Role Perspective; Emotional Closeness Perspective; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 33 | Dorros | 2010 | 26% (95) |

Mean age (SD):

51.7 (14.8) Race/Ethnicity: 87% White, 12% Hispanic Relationship to patient: 77% Spouse 17% Daughter, 6% Other |

100% (95) |

Mean age (SD):

54.1 (10.6) Race/Ethnicity: 85% White, 14% Hispanic Diagnosis: 100% Breast Stage: 33% I, 53% II, 14% III |

|

Gender Role Perspective; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 34 | Wadhwa et al. | 2013 | 64.9% (191) |

Mean age: 57 Race/Ethnicity: 82.2% European Relationship to patient: 83.8% Spouse, 11% Offspring, 5.2% Other |

46.6% (191) |

Mean age: 61 Race/Ethnicity: 84.8% European Diagnosis: 37.1% GI, 17.8% Genitourinary, 17.3% Breast, 16.2% Lung, 11% Gynecologic Stage: Not reported |

|

Gender Role Perspective; Lifespan Perspective; Role Strain Theory; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 35 | Gaugler et al. | 2008 | 72.1% (183) |

Mean age (SD):

56.1 (10.6) Race/Ethnicity: 74.3% White Relationship to patient: 71.6% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age (SD):

62.0 (12.6) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 44% Lung, 27% Head/Neck, 21% Brain, 18% Gastrointestinal, 15% Breast, 13% Bone/Leukemia, 13% Prostate, 9% Pancreas/Liver, 8% Gynecological, 3% Skin Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity Theory; Role Strain Theory; “Doing Gender” |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| • Caregiver Outcomes at the Individual Level | ||||||||

| 36 | Kim et al. | 2006 | 55.7% (429) |

Mean age: 59 Race/Ethnicity: 96% Caucasian Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 10 common cancers Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 37 | Hagedoorn | 2002 | 47.1% (68) |

Mean age (SD):

54 (11) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Relationship to patient: 100% Partner |

52.9% (68) |

Mean age (SD):

53 (11) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Diagnosis: 21% Breast, 18% Intestinal, 16% Skin, 9% Larynx, 6% Bone, Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 38 | Kim et al. | 2007 | 61.8% (448) |

Mean age (SD):

54.8 (12.6) Race/Ethnicity: 94.2% Caucasian Relationship to patient: 78.3% Spouse; 21.7% Offspring |

52.8% (448) |

Mean age (SD):

60.0 (11.5) Race/Ethnicity: 93.1% Caucasian Diagnosis: 21.2% Prostate, 21.0% Breast, 14.7% Colorectal, 10.3% Lung, 25.3% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Strain Theory; Lifespan Perspective; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 39 | Kim et al. | 2008a | 100% (98) |

Mean age (SD):

40.8 (11.7) Race/Ethnicity: 89% Caucasian Relationship to patient: 100% Adult daughters |

100% (98) |

Mean age (SD):

67.1 (12.0) Race/Ethnicity: 91% Caucasian Diagnosis: 25% Breast, 15% Colorectal, 13% Ovarian, 28% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Lifespan Perspective; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 40 | Ussher & Perz | 2010 | 68% (484) |

Mean age (SD):

55.1 (13.2) Race/Ethnicity: 94.4% Caucasian, 4.6% Asian, 0.8% Aboriginal Relationship to patient: 71.9% Partner, 11.9% Child, 14.2% Other |

Not reported |

Mean age (SD):

59.2 (11.6) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 17.3% Breast, 12.9% Colorectal, 10.6% Hematological, 48% Other Stage: 8.9% Early, 38.3% Advanced |

|

“Doing Gender”; Role Identity Theory; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Qualitative | ||||||||

| 41 | Fitzel & Pakenham | 2010 | 71.4% (622) |

Mean age (SD):

59.5 (12.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Australian sample Relationship to patient: 84% Spouse, 12% Family |

34.6% (622) |

Mean age (SD):

61.4 (9.3) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Australian sample Diagnosis: 100% Colorectal Stage: 22% I, 26% II, 43% III, 2% IV |

|

Role Identity Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 42 | Pikler & Brown | 2010 | 45.5% (111) |

Mean age (SD):

57.5 (13.2) Race/Ethnicity*: 76.3% White, 16.3% African American/Black, 7.4% Other Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse *Across patients and caregiver |

68.8% (189) |

Mean age (SD):

55.5 (11.9) Race/Ethnicity: See Caregiver Characteristics Diagnosis: Varied-distribution not reported Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 43 | Goldzweig et al. | 2009a | 61% (231) |

Mean age (SD):

69.2 (7.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

39% (231) |

Mean age (SD):

70.7 (6.2) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Diagnosis: 100% Colorectal Stage: 14% I, 61% II, 23% III |

|

Role Identity theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 44 | Baider et al. | 2003 | 41.1% (287) |

Mean age (SD):

60.0 (11.7) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

48.9% (287) |

Mean age (SD):

59.9 (11.6) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Diagnosis: 41% Prostate, 59% Breast Stage: 100% I-III |

|

Role Identity Theory; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 45 | Goldzweig et al. | 2009b | 0% (153) |

Mean age (SD):

65.3 (10.3) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

0% (239) |

Mean age (SD):

67.9 (9.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Diagnosis: 100% Colorectal Stage: 17.9% 0-I, 60.3% II, 21.8% III |

|

Role Identity Theory; “Doing gender” Theory; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 46 | Ezer et al. | 2011 | 100% (81) |

Mean age (SD): 63.2 Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-French Canadian sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

0% (81) |

Mean age (SD): 67.7 Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-French Canadian sample Diagnosis: 100% Prostate Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 47 | Tuinstra et al. | 2004 | 65% (137) |

Mean age (SD):

59.2 (10.3) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

35% (137) |

Mean age (SD):

59.0 (11.3) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Dutch sample Diagnosis: 100% Colorectal Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Identity Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 48 | Spillers et al. | 2008 | 66.8% (635) |

Mean age (SD):

55.22 (12.88) Race/Ethnicity: 93.2% Caucasian Relationship to patient: 66.6% Spouse, 19.1% Adult Child, 14.3% Other |

57.4% (635) |

Mean age (SD):

59.2 (12.4) Race/Ethnicity: 92.1% Caucasian Diagnosis: 25% Breast, 20% Prostate, 13% Colorectal, 11% Lung, 18% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Strain Theory; Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 49 | Papastavrou et al. | 2009 | 54.6% (130) |

Mean age (SD):

50.7 (13.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Greek sample Relationship to patient: 36.9% Spouse, 14.6% Son, 22.3% Daughter, 15.4% Sibling, 10.8% Other |

60% (130) |

Mean age (SD):

60.1 (15.0) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Greek-Cypriot sample Diagnosis: 25.4% Breast, 16.9% Colon, 13.1% Gynecological, 10.8% Lung, 25.7% Others Stage: 8.5% Advanced |

|

Role Strain Theory; Transactional Stress theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 50 | Alptekin et al. | 2010 | 53.3% (126) |

Mean age (SD):

45.0 (11.6) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Turkish sample Relationship to patient: 46.8% Spouse, 36.5% Child, 12.7% Sibling, 4% Other |

66.7% (126) |

Mean age (SD):

56.4 (11.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Turkish sample Diagnosis: 29.4% Gastrointestinal, 25.4% Gynecologic, 25.4% Breast, 11.1% Respiratory System, 8.7% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Enhancement Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 51 | Kang et al. | 2013 | 58.5% (501) |

Mean age (SD):

53.2 (12.5) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Korean sample Relationship to patient: 46.5% Spouse |

47.2% (492) |

Mean age (SD):

64.3 (13.7) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Korean sample Diagnosis: 18.9 % Lung, 17.9% Gastric, 63% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Role enhancement theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 52 | Kim et al. | 2008 | 50.5% (314) |

Mean age (SD):

56.5 (10.6) Race/Ethnicity: 90.8% White Relationship to patient: 65.5% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age (SD): Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 25% Breast, 24% Prostate, 11% Colorectal, 11% Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, 14% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Attachment Theory; Self-Determination Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 53 | Künzler et al. | 2014 | 61% (154) |

Mean age (SD):

56.8 (14.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

39% (154) |

Mean age (SD):

57.5 (12.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss Sample Diagnosis: 18% Hematologic, 17.9% Lung, 8.5% Liver, 15.9%, Colorectal, 10.7% Genitourinary, 22.5% Other Stage: 100% 0-IV |

|

Interdependence Theory; Role Enhancement Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 54 | Barnoy et al. | 2006 | 54.1% (98) |

Mean age (SD):

53.8 (13.8) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Relationship to patient: 100% Partner |

45.9% (98) |

Mean age (SD):

53.8 (13.8) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Israeli sample Diagnosis: Mix of Breast, Ovarian, Prostate, Colon, Lung, Liver, Pancreas, Brain Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 55 | Colgrove et al. | 2007 | 54.3% (403) |

Mean age (SD):

59 (11) Race/Ethnicity: 95.80% White Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age (SD):

Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 26% Prostate, 23% Breast, 15% Colorectal, 32% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 56 | Dunn et al. | 2012 | 71.8% (85) |

Mean age (SD):

62.5 (10.5) Race/Ethnicity: 80% Caucasian, 10.6% African American, 4.7% Asian, 4.7% Other Relationship to patient: 100% Primary caregiver |

44.6% (167) |

Mean age (SD):

60.9 (11.6) Race/Ethnicity: 71.9% Caucasian, 15.0% African American, 7.2% Asian, 5.9% Other Diagnosis/Stage: 48.8% Prostate, 38.1% Breast, 13.2 Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Role Strain Theory, Transactional Stress Theory, Lifespan Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 57 | Friðriksdóttir et al. | 2011 | 62% (223) |

Mean age (SD):

56 (13.6) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Icelandic sample Relationship to patient: 64% Spouse, 36% Other |

Not reported |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Icelandic sample Diagnosis: Not reported Stage: Not reported |

|

Lifespan theory, Role Strain Theory, Transactional Stress theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 58 | Gustavsson-Lilius et al. | 2007 | 55.3% (123) |

Mean age (SD):

59 (9.1) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Finnish sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

44.7% (123) |

Mean age (SD):

59 (8.4) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Finnish sample Diagnosis: 43.1% Beast, 27.6% Prostate, 9.7% Gynecological, 8.9% Gastrointestinal Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 59 | Hagedoorn | 2000 | 59.5% (173) |

Mean age (SD):

56.4 (9.1) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Relationship to patient: 100% Partner |

40.46% (173) |

Mean age (SD):

56.8 (9.0) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Diagnosis: 25.4% Head-Neck, 25.4% Multiple myeloma, 19.2% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory; Gender Role Perspective |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 60 | Haley | 2003 | 79% (80) |

Mean age: 70 Race/Ethnicity: 84% Caucasian Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age: 70 Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - US sample Diagnosis: 50% Dementia, 50% Cancer Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 61 | Künzler et al. | 2011 | 63% (137) |

Mean age (SD): 57 (14)* Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse * Across patients and caregivers |

47% (218) |

Mean age: See caregiver age Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss Sample Diagnosis: 19% Breast, 18%, Hematological, 18% Lung, 45% Other Stage: 18% I, 18% II, 26% III, 38% IV |

|

Transactional Stress theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 62 | Langer et al. | 2003 | 50.4% (131) |

Mean age (SD): 43.1 (9.8) Race/Ethnicity: 90.6% Caucasian, 4.7% Hispanic, 4.8% Other Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

51.1% (131) |

Mean age (SD):

42.9 (9.3) Race/Ethnicity: 94.7% Caucasian, 4.0% Hispanic Diagnosis: 36.6% CML (Chronic Myeloid Leukemia), 19.1% Acute Leukemia (AL), 44% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Interdependence theory; Transactional Stress theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 63 | Langer et al. | 2010 | 47.9% (121) |

Mean age (SD):

43.5 (9.8) Race/Ethnicity: 90.1% Caucasian, 5% Hispanic, Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

52.1% (121) |

Mean age (SD):

43.7 (9.0) Race/Ethnicity: 92.6% Caucasian, 5.8% Hispanic Diagnosis: 35.5% CML, 18.2% AL, 46.3% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Interdependence Theory; Transactional Stress theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 64 | Litzelman & Yabroff | 2015 | 46.9% (910) |

Mean age (SD):

61.5 (9.8) Race/Ethnicity: 65.5% White non-Hispanic 34.5% Other Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

53.1% (910) |

Mean age (SD):

60.4 (13.1) Race/Ethnicity: 64% White non-Hispanic 35% Other Diagnosis: 21.1% Prostate, 18.8% Breast, 5.3% Colorectal, 10.6% Multiple, 36.0% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory; Interdependence theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 65 | Nijboer et al. | 2000 | 64% (148) |

Mean age (SD):

63 (11) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Relationship to patient: 100% Partner |

Not reported |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Diagnosis: 100% Colorectal Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 66 | Nijboer et al. | 2001 | 64% (148) |

Mean age (SD):

63 (11) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported - Dutch sample Diagnosis: 100% Colorectal Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress theory |

| Caregivers only; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 67 | Song et al. | 2014 | 58.5% (501) |

Mean age (SD):

53.2 (12.5) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Korean sample Relationship to patient: 46.5% Spouse 53.5% Other |

47.2% (492) |

Mean age (SD):

64.3 (13.7) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Korean sample Diagnosis: 18.9 % Lung, 17.9% Gastric, 69.1% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 68 | Valeberg et al. | 2013 | 39% (159) |

Mean age (SD):

56.7 (12.2) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Norwegian sample Relationship to patient: 89.5% Spouse, 5.6% Friend, 4.3% Offspring, 1% Sibling |

68.6% (159) |

Mean age (SD):

58.5 (11.1) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Norwegian sample Diagnosis/Stage: 46.5% Breast, 18.2% Prostate, 15.6% Colorectal, 19.7% Other Stage: 28.9% 0-II; 81.1% III-IV |

|

Transactional Stress theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 69 | Segrin et al. | 2012 | 94% (70) |

Mean age (SD):

61.1 (10.9) Race/Ethnicity: 81% White, 9% Black, 4% Latina/o, 3% Asian Relationship to patient: 83% Spouse, 10% Friend, 4% Sibling, 3% Son/Daughter |

0% (70) |

Mean age (SD):

66.7 (9.3) Race/ethnicity: 84% White, 9% Black, 7% Latino Diagnosis: 100% Prostate Stage: 36% I, 19% II, 19% III, 26% IV |

|

Transactional Stress Theory; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 70 | Kim et al. | 2010 | 64.7% (896) |

Mean age (SD):

54.4 (12.8) Race/Ethnicity: 90.5% White/Caucasian Relationship to patient: 65.5% Spouse |

Not reported |

Mean age (SD):

Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 27% Breast, 18% Ovarian, 14% Lung, 11% Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, 9% Prostate, 6% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Lifespan Perspective; Role Strain Theory, Transactional Stress Theory |

| Caregivers only; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| • Caregiver Outcomes at the Relational Level/Context | ||||||||

| 71 | McLean et al. | 2011 | 39.1% (46) |

Mean age (SD):

49.3 (11.8) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Canadian sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

60.9% (46) |

Mean age (SD):

49.7 (11.5) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Canadian sample Diagnosis: 26.1% Breast, 17.4% Head & Neck, 15.2 % Blood, 41.3% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Attachment theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 72 | Kim et al. | 2015a | 63.1% (369) |

Mean age (SD):

55.0 (10.3) Race/Ethnicity: 90% White Relationship to patient: 73% Spouses, 14% Offspring, 6% Sibling |

Not reported |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: Not reported Diagnosis: 29.5% Breast, 21.7% Prostate, 12.5% Colorectal, 8.4% Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, 13% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Self-Determination Theory |

| Caregivers only; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 73 | Segrin et al. | 2005 | 20% (48) |

Mean age (SD):

50.6 (14.5) Race/Ethnicity: 86% White, 14% Hispanic Relationship to patient: 67% Husband, 17% Daughter, 8% Friend, 8% Other |

100% (48) |

Mean age (SD):

54.4 (10.0) Race/ethnicity: 80% White, 20% Hispanic Diagnosis: 100% Breast Stage: 100% I-III |

|

Role Identity theory; Transactional Stress Theory; Emotional Closeness Perspective; Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 74 | Zwahlen et al. | 2010 | 54% (224) |

Mean age: 59.5 Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss sample Relationship to patient: 83.8% Spouse, 11% Offsping, 5.2% Other |

42% (224) |

Mean age: 60 Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss sample Diagnosis: 22.3% Lymphoma, 17.0% skin, 14.3% Intestinal, 62.8% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Interdependence Theory; Gender Role Perspective; Role Enhancement Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 75 | Kim et al. | 2015b | 77.5% (398) |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: 76.9% Caucasian, 14.8% African American, 3.0% Hispanic, 5.3% Other Relationship to patient: 63.8% Spouse, 14.9% Offspring, 5.3% Sibling, 6.9% Other |

35.4% (398) |

Mean age: Not reported Race/Ethnicity: 78.6% Caucasian, 15.1% African American, 2.8% Hispanic, 3.5% Other Diagnosis: 53.3% Colorectal, 46.6% Lung Stage: 1% 0, 31.7% I, 19.3% II, 34.4% III, 13.6% IV |

|

Interdependence Theory; Gender Role Perspective |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional (caregivers)/Longitudinal (patients); Quantitative | ||||||||

| 76 | Moser et al. | 2013 | 61% (154) |

Mean age (SD):

56.8 (13.3) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss Sample Relationship to patient: 100% Partner |

39% (154) |

Mean age (SD):

57.5 (9.2) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss Sample Diagnosis: 27.7% Hematologic, 27.5% Lung, 24.5% Bowel, 23.4% Breast, 24.4% Other Stage: 15.1% I, 18.9% II, 27.6% III, 38.6% IV |

|

Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Longitudinal; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 77 | McPherson et al. | 2008 | 68% (66) |

Mean age (SD):

61.0 (13.8) Race/Ethnicity: 88% Caucasian, 12% Other Relationship to patient: Mixed |

43% (66) |

Mean age (SD):

68.0 (11.6) Race/Ethnicity: 91% Caucasian, 9% Other Diagnosis: 28.8% Lung, 24.2% GI, 47.4% Other Stage: 100% III-IV |

|

Interdependence Theory; Gender Role Perspective |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

| 78 | Drabe | 2013 | 55% (156) |

Mean age (SD):

57.9 (21.8) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss sample Relationship to patient: 100% Spouse |

45% (149) |

Mean age (SD):

58.5 (12.8) Race/Ethnicity: Not reported-Swiss Sample Diagnosis: 22.5% Lymphoma, 17.2% Skin, 9.6% Breast, 14.8% Intestinal, 9.6% Lung, 6.2% Leukemia, 6.7% Myeloma, 6.6% Other Stage: Not reported |

|

Interdependence Theory |

| Both caregivers & patients; Cross-sectional; Quantitative | ||||||||

Caregiver Selection.

We hypothesized that regardless of one’s gender, persons who are retired or empty-nesters (cf. the lifespan perspective), and who live in the same household or nearby are likely to provide tangible and medical care; those who are capable of navigating medical and support systems are likely to provide informational care (cf. the doing gender perspective). On the contrary, women (wives, daughters, mothers, girl-friends) are more likely to provide emotional support, regardless of physical proximity (cf. the gender role perspective) and females are more likely to be emotionally connected to the patient (cf. the emotional closeness perspective).

A few studies to date have provided empirical support for these predictions. For example, emotional support immediately after cancer surgery has been found to be provided equally by both genders; emotional support declined significantly only among male caregivers at one and six months after the surgery.19, 25–27 In contrast, cancer caregivers from a nationally representative sample of adults were predominantly female (68%); this pattern was the same as caregivers of other major illnesses requiring care, such dementia or diabetes, whereas the gender of caregivers of frail elderly was almost equally distributed.4 Close friends or non-relatives were more likely to care for cancer patients, whereas grandchildren were more so for frail elderly.4

Female caregivers, compared with male caregivers, reported more involvement in medical care,28–33 and more hours spent for caregiving and more subsequent changes to their work situations since initation of their cancer caregiver role.34 In addition, employed female caregivers reported providing more support to the patients than unemployed male caregivers.35

Overall, these findings suggest that women are more likely to partake in caregiving, although the patients’ needs and availability of the caregivers, rather than the caregivers’ gender per se, are more likely to be primary factors for cancer caregiver selection. This supports the doing gender perspective. A larger proportion of females compared with males is represented in cancer caregiving, supporting also the gender role perspective.

Caregiving Outcomes at the Individual Level.

Male spousal caregivers of patients with breast or gynecologic cancer reported difficulty with communicating with family and friends regarding the wives’/partners’ cancer soon after the diagnosis, and carrying out housekeeping and child care throughout the first year, which are traditionally female gender tasks.25 Male caregivers have also reported greater distress when their wives had worse psychosocial functioning,36 whereas female caregivers have reported greater distress when they perceived themselves providing little support to the patient.37 Social standards imposed on female caregvers of taking on more caregiving tasks than they can handle has often been associated with their greater levels of “burn-out” and lack of self care.26, 30–33, 35

Both male and female caregivers reported that taking on non-traditional roles presented challenges.26 For example, for female caregivers, yardwork, household maintenance, and driving were difficult, while for male caregivers, increased housework such as cooking and cleaning presented challenges.26 However, later on in the patient’s treatment, male caregivers reported being more comfortable with non-traditional roles such as housework, cooking, and shopping or the family.25 Such gender differences in individuals’ adjustment outcomes have also been seen in some studies of adult offspring caregivers, adding support to the lifespan perspective.38, 39

Gender also influenced coping strategies. Male caregivers tended to report more difficulty talking about their emotions and asking for support.25 Both male and female caregivers used self-silencing in order to see to the patient’s needs; males attributed this to the masculinity norm that prohibits self-expression, whereas for females, self-silencing was more a matter of sacrificing to prioritize the patient.40 The use of coping strategies that involve avoiding talking about feelings related to higher distress and anxiety among both genders.41,42

The coping strategy of substance use was utilized more frequently by male caregivers, resulting in their lower positive affect than female caregivers.41 Receipt of social support has also related to only male caregivers’ higher distress and guilt,29, 43,44, which may be attributable to their emphasis on independence.45 In addition, male prostate cancer patients were most concerned with their sexual adjustment issues, whereas their wives were most concerned with (dis)satisfaction with healthcare.46 These findings support gender role identity theory. However, one study reported male caregivers’ higher distress than male patients; and female patients’ higher distress than female caregivers, suggesting the additional influence of the patient vs caregiver role in individuals’ adjustment outcomes.47

Other existing social roles are another complicating factor. Caregivers with children living at home reported higher anxiety than those without. Adult-offspring caregivers have also reported greater caregiver guilt48 and stress than spousal and other caregivers. These findings support role strain theory, in which increased demands from the additional role of caregiver compete for limited resources against demands from preexisting social roles, thus yielding greater distress. This was more the case among female caregivers who often neglect self-care in order to carry out the caregiver role26, 38 and among employed female caregivers, who were more likely to provide instrumental care than men (regardless of employment status) and who reported greater emotional distress and caregiving burden.30, 35

Female caregivers have also reported greater financial burden, which could contribute to perceived role strain as they are required to simultaneously provide caregiving and manage and maintain financial resources for the family.49 However, being employed per se, independent of gender, has been a protective factor against low quality of life,50 supporting role enhancement theory, in which being employed boosts personal and social resources for better quality of life. The new additional caregiver role has also related to greater benefit finding, appreciating others, and reprioriziting life values,39,51–53 again supporting role enhancement theory.

Consistent gender differences in cancer caregiving stress (females reporting greater stress) have been reported in numerous studies grounded on transaction stress theory and its descendants: due in part to men’s having higher perceived resources (e.g., self-esteem or mastery) and taking personal gratification in being a caregiver.38 The disproportionate stress levels by gender have in turn been related to poorer mental and physical health outcomes of female caregivers, compared to male counterparts.34, 35,27,40, 47, 48, 51, 53–69 Among women, particularly young to middle-aged female caregivers (also supporting the lifespan perspective), greater perceived demands, such as greater unmet needs in various care domains, resulted in higher caregiving stress.70 Being younger and being parents of young children have related to higher anxiety levels,56, 57 again supporting the lifespan perspective.

Overall, findings support transactional stress theory, role identity theory, and role strain theory among individual-oriented gender theories. Findings suggest that female family members are more likely than males to identify caregiving for a relative with cancer as their new role. Yet due in part to exceeding demands from existing social roles and limited resources, they are prone to stress and compromised mental and physical health from caregiving. However, because the majority of studies did not test gender effects in the relation of demands or resources linking to individuals’ adjustment outcomes, the adequacy of the transactional stress theory in gender research is inconclusive.

Caregiving Outcomes at the Relational/Context Level.

Adult attachment orientations were differentially related to caregiving behaviors by gender of the caregivers. For example, among female caregivers only, secure attachment related to more frequent emotional care, anxious attachment related to more frequent tangible care,28 and avoidant attachment related to greater marital distress.52,71 Among male caregivers only, avoidant attachment related to less frequent emotional care, and anxious attachment related to less frequent medical care.28

Supporting self-determination theory (SDT), autonomous caregiving motives have also related to better caregiving outcomes, although this was the case only for male caregivers.52, 72 Caregiving motivations also have long-term impact on quality of life, once again only among male cancer caregivers: Autonomous caregiving motives link to greater likelihood of finding meaning, making peace, and relying on faith, which in turn relates to better mental and physical health years later.72

Supporting the emotional closeness perspective, female caregivers reported higher levels of psychological distress and decreased relationship satisfaction when their patients reported greater distress.44, 69 Moreover, discrepant ratings of marital satisfaction were more associated with greater distress for females than males.32

Most of the studies examining interdependence theory on close relationships have looked at breast or prostate cancer patients and their heterosexual spousal caregivers.25, 31, 69, 73 For example, prostate cancer patients’ disease-specific quality of life was associated with their female partner’s psychological functioning,69 which was not the case among breast cancer dyads.73 Breast cancer patients’ greater depression and stress were associated with their (mainly) male partners’ poorer physical health and well-being.33 In the same study, the women’s greater depression and their partners’ high levels of stress were associated with the partners’ poorer physical health, suggesting that the unconventional gender role for male caregivers contributed to greater stress and worse health outcomes.

A meta-analysis examining gender effects across dyadic studies with cancer found that patients reported greater distress than did their caregivers when the patient was female, whereas caregivers reported greater distress than did patients when the patient was male, suggesting distress was determined by gender rather than by patient versus caregiver role.59 The same was the case for posttraumatic growth: women (whether caregiver or patient) reported greater posttraumatic growth than men following the cancer diagnosis,74 supporting the theories/perspectives at the individual-level, such as gender role perspective and transaction stress theory.

However, one study examined this interdependent relationship among mothers with cancer and their adult caregiving daughters. In these dyads of women, the mothers’ (patients) greater distress was related to the daughters’ (caregivers) better mental health but poorer physical health, in addition to each person’s psychological distress being the strongest predictor of her own mental and physical health.39 Similar patterns were found with non-sex-specific cancers, such as colorectal and lung cancer caregiver-patient dyads. For both patients and caregivers, depressive symptom level was uniquely associated with one’s own concurrent mental and physical health. Female patients’ depressive symptoms were also related to better mental health and poorer physical health of their caregivers of any gender, particularly when the pair’s depressive symptoms were at similar, elevated levels. On the other hand, male patients’ elevated depressive symptoms related to their caregivers’ (mainly females) poorer mental health.75

Such crossover and gender effects were also found in a 3-year longitudinal study with mixed types and stages of cancer, in which male patients’ distress influenced their partners’ later distress but not the other way around.76 In addition, when caregivers were men, there was lower concordance between ratings of the patient’s physical symptoms and distress,19,77 supporting the gender role as well as interdependence perspectives.

Decreased relationship satisfaction has related to anxiety and depression and reduced quality of life in male partners and patients, and female partners, whereas this was not the case for female patients.78 Female caregivers were more susceptible than male caregivers to changes in marriage satisfaction following cancer diagnosis.62, 63 Findings suggest that relationship satisfaction moderates the associations of the interdependence between caregiver and patient with their health outcomes. None of the studies reviewed here directly supported the social exchange theory perspective.

In summary, relational factors, such as secure attachment orientation, autonomous caregiving motives, and interdependence between patients and their caregivers, all appear to be associated with better mental and physical health consequences of caregiving, though the strength of the association depends somewhat on the gender of caregivers or patients.

Discussion

Growing evidence suggests that gender plays a role in cancer caregivers’ diverse experiences and consequences, depending also on relationship characteristics of the caregivers with patients. However, investigation driven by gender theories in this emerging field is, to date, lacking.

Does gender matter in cancer caregiver selection?

The majority of studies have affirmed a bias toward females being caregivers, supporting the gender role perspective.19, 26, 30, 34, 35 However, studies that included both genders of caregivers and targeted patients with non-gender specific cancer,40, 45 have increasly supported the “doing gender” perspective, in which caregivers are selected based more on their availability and the patients’ needs, rather than the caregivers’ gender per se. Because the majority of studies reviewed were cross-sectional, small-size, and convenience samples, the possibility of selection bias in caregiver participants and general gender differences in study participation (greater female participation)2 cannot be ruled out. Population-based, longitudinal studies, including a wider social network of caregivers of the patient, and the information about each caregiver’s choice of carrying out certain care tasks, will be necessary to address this question properly.

Does gender matter in one’s cancer caregiving outcomes?

The majority of studies have documented greater adverse outcomes of caregiving among female caregivers than male caregivers, due in part to female caregivers identifying daily and challenging care tasks as their job while juggling other existing social role demands.36–38, 40–49 This supports role identity theory and role strain theory. Whether female caregivers’ disproportionate burden of carrying out the cancer caregiving role is due to either lack of resources and greater demands in the family or closer relationships among females in general (according to transactional stress theory) remains an open question. Most of the studies that provided support for the transactional stress theory did not test the effects of gender on the relations of demands and resources with the outcomes that were measured. Investigating the role of gender as a moderator or mediator of the relations of caregivers’ demographic and psychosocial characteristics with outcomes of caregiving experience is worth further attention.

Does caregivers’ gender matter in their patients’ outcomes, and vice versa?

The majority of emerging studies in cancer caregiver research have examined the impact of cancer at the interpersonal, dyadic level. The findings have affirmed that gender matters here, supporting the role of interpersonal characteristics, such as attachment orientation, caregiving motives, and interdependence between caregivers and their patients, as being related not only to one’s own outcomes but also the partners’. However, again knowledge about the role of gender in the dyadic associations is lacking, due mainly to the focus of existing dyadic research on patients with gender-specific cancers and their heterosexual caregivers, which prevents differentiating gender effects from patient-vs-caregiver role effects.

Role of Gender in Cancer Caregiving Research

The overall gender-related findings from the studies reviewed here are similar to those from the general caregiver research, which has come mainly from dementia or frail elder care.2 Namely, females are more likely to be involved in caregiving; and female spousal caregivers are more likely to report greater psychological distress. However, cancer caregiving has a trajectory and corresponding burdens to family caregivers that differ from those of other chronic diseases.4 Family members often face sudden diagnosis of cancer in the family bringing immediate turmoil. Family caregivers are also “on call” throughout different phases of cancer survivorship; the patient’s need for care tends to be sporadic, peaking around time of diagnosis and treatment, and again at the end-of-life phase. Given this trajectory, who is likely to become a family cancer caregiver depends heavily upon who is immediately available and present. This is most likely an adult living with the patient in the same household or nearby for managing practical concerns, while for managing emotional and psychosocial concerns it could be any family member or close friend. Gender of the caregiver at this phase of the illness trajectory most likely depends on what kind of care tasks are required, rather than the caregivers’ gender.

Cancer caregivers also often move in and out of caregiving over several years during the care recipient’s illness trajectory—as cancer remits for years but in some cases recurs.4 Some caregivers, however, remain actively involved in cancer care several years after initial diagnosis. Actively providing care years after the initial diagnosis must be especially stressful, because it may bring back the original distress in addition to the current difficulties of caregiving.75 Other caregivers become bereaved, when the patients’ survivorship ends. Of course, many survivors remain in remission several years after diagnosis, so their family caregivers become former caregivers. All of these issues emphasize the importance for future studies to address unanswered questions regarding the role of gender across these various phases and trajectory of cancer.

Another factor characterizes the caregiving situation is the interdependence between patients and their caregivers. Relationship-oriented gender theories thus have particular relevance in understanding the experiences and consequencies of adult cancer caregiving. However, most studies examining caregiving outcomes at the relational level have looked at breast or prostate cancer patients and their heterosexual spousal caregivers. This does not allow distinguishing gender effects from patient-vs-caregiver role effects. Studying patients with non-gender specific cancer and their caregivers of any gender will help to address the role of gender in cancer caregiving at the relational level.

Most of the studies have also examined the negative impact of cancer, such as psychological distress. Having cancer in the family and losing family member to cancer also envoke resilence. Examining the potential positive impact of cancer, such as benefit finding, posttraumatic growth, and stress-related growth;51–53 and the role of gender in such phenomena will provide a fuller picture of the role of gender in cancer caregiving. Longitudinal studies with large cohorts of cancer caregivers from diverse backgrounds both socioculturally and in terms of life stage will be crucial to guide the future of gender-oriented cancer caregiving research reflecting many understudied, hidden faces of family cancer caregivers.

It is also important to note that all existing studies that were reviewed here relied on self-reports. The greater distress of females (both caregivers and patients) may be attributable to sex differences in stress regulation processes.79 Systematic investigation of the role of gender and biological sex in cardiovascular, immunological, and neuroendocrinological stress regulatatory processes may shed light on better understanding of gender disparities in cancer caregiving.

Clinical Implications

Although still small in number, studies reviewed suggest that gender theories provide useful guidance for identifying factors associated with caregiving outcomes and implementing appropriate screening for such factors and developing adequate psychosocial interventions to address them. For example, since the trajectory of caregivership relies on the patients’ illness prognosis, not the caregivers’ gender, broad stress-coping theories, such as transactional stress theory, would be applicable to describing and predicting caregiving processes and outcomes.

Traditional cognitive behavioral stress management interventions and problem-solving interventions80 could be effective in helping cancer caregivers throughout their variable trajectory, by providing generalizable skills and knowledge that are adaptive to unforeseeable illness trajectories of their patients. Such intervention programs should educate male caregivers on how to effectively provide emotional support to their female patients. Educating caregivers regarding how best to utilize alternate or additional resources for obtaining emotional support for themselves may protect caregivers from compromised quality of life due to cancer in the family. Couple-based approaches that address psychological distress, couple communication, and relationship functioning of cancer patients and their caregivers,80 could also be useful. These are another broad topic in which gender and gender-related factors may play important roles in various aspects of the quality of life of the caregiver population. They thus should be incorporated in the development of evidence-based interventions for cancer caregivers. The extent to which couple-based interventions are applicable to non-spousal pairs and same-sex caregiver-patient dyads also needs to be investigated.

Study Limitations

This review was restricted to adults (either patients or caregivers), published (as opposed to grayarea or unpublished), and published in English, all of which limit the generalizability of our conclusions. The gender theories selected to evaluate current cancer caregiving studies were chosen from the literature of psychology. Gender theories also exist in other diciplines, and the nuances of the theories from different diciplines can be quit different. Future investigations of cancer caregiving involvement and consequences of caregiving for pediatric patients and of child caregivers by multiple sites and multiple cultures are warranted. Future studies examining the roles of fluidity and plurality of gender identity, and biological sex in involvement in cancer caregiving and its health concequences are also warranted.

Conclusions

Gender theories have been well established and gender differences in psychological distress when facing cancer (regardless of patient vs caregiver role) have been solidly documented. Despite lack of gender-theory-driven research in cancer caregiving and Psycho-Oncology in general, the utility of gender theories in identifying sub-groups of caregiver-patient dyads who are vulnerable to the adverse effects of cancer in the family and in developing evidence-based interventions is promising. Integration of the issues related to the medical trajectory of the patients, lifespan stage of the caregivers, sociocultural resources and risk factors to this emerging area of gender-oriented research and practice in cancer caregiving is warranted for improving quality of life of persons touched by cancer and minimizing premature morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgement:

Writing of this manuscript was supported by American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grants (121909-RSG-12-042-01-CPPB) and National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR016838) to the first author. The authors extend their appreciation to all the families who participated in this investigation. The first author dedicates this research to the memory of Heekyoung Kim.

References

- 1.National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregiving in the US. 2015.

- 2.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(1):P33–P45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim Y, Schulz R. Family caregivers’ strains: comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. Journal of Aging and Health. 2008;20(5):483–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagly AH, Wood W. Social role theory In van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, & Higgins ET (Eds). Handbook of Theories in Social Psychology. 2012. pp. 458–476. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connell RW. Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.West C, Zimmerman DH. Doing gender. Gender & society. 1987;1(2):125–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreppner K, Lerner RM. Family Systems and Life-span Development: Psychology Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pietromonaco PR, Uchino B, Dunkel Schetter C. Close relationship processes and health: implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychology. 2013;32(5):499–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin. 2003;129(6):946–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychological bulletin. 2008;134(1):1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarus RS. Folkman S. (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: pringer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedemann M-L, Buckwalter KC. Family caregiver role and burden related to gender and family relationships. Journal of family nursing. 2014;20(3):313–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid J, Hardy M. Multiple roles and well-being among midlife women: Testing role strain and role enhancement theories. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1999;54(6):S329–S338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer BJ. Gain in the caregiving experience: Where are we? What next? The Gerontologist. 1997;37(2):218–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rusbult CE, Van Lange PA. Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual review of psychology. 2003;54(1):351–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1987;52(3):511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luszczynska A, Boehmer S, Knoll N, Schulz U, Schwarzer R. Emotional support for men and women with cancer: Do patients receive what their partners provide? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;14(3):156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness: Guilford Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodges L, Humphris G, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Social science & medicine. 2005;60(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitceathly C, Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: a review. European Journal of cancer. 2003;39(11):1517–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ. Gender in Psycho-oncology: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Mak Y, Loke A. Spouses’ experience of caregiving for cancer patients: a literature review. International Nursing Review. 2013;60(2):178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez V, Copp G, Molassiotis A. Male caregivers of patients with breast and gynecologic cancer: experiences from caring for their spouses and partners. Cancer nursing. 2012;35(6):402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ussher JM, Sandoval M, Perz J, Wong WT, Butow P. The gendered construction and experience of difficulties and rewards in cancer care. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23(7):900–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segrin C, Badger TA. Psychological distress in different social network members of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Research in nursing & health. 2010;33(5):450–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y, Carver CS. Frequency and difficulty in caregiving among spouses of individuals with cancer: Effects of adult attachment and gender. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(8):714–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliffe JL, Mróz LW, Bottorff JL, Braybrook DE, Ward A, Goldenberg LS. Heterosexual couples and prostate cancer support groups: a gender relations analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2015;23(4):1127–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perz J, Ussher J, Butow P, Wain G. Gender differences in cancer carer psychological distress: an analysis of moderators and mediators. European journal of cancer care. 2011;20(5):610–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw CK, Smith TG. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(2):230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenewein J, Zwahlen R, Zwahlen D, Drabe N, Moergeli H, Büchi S. Quality of life and dyadic adjustment in oral cancer patients and their female partners. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2008;17(2):127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorros SM, Card NA, Segrin C, Badger TA. Interdependence in women with breast cancer and their partners: an interindividual model of distress. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2010;78(1):121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wadhwa D, Burman D, Swami N, Rodin G, Lo C, Zimmermann C. Quality of life and mental health in caregivers of outpatients with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(2):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaugler JE, Given WC, Linder J, Kataria R, Tucker G, Regine WF. Work, gender, and stress in family cancer caregiving. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16(4):347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL. Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(12):1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Buunk BP, Wobbes T. Failing in spousal caregiving: The ‘identity-relevant stress’ hypothesis to explain sex differences in caregiver distress. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7(4):481–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL. Cancer caregivers’ quality of life: effects of gender, relationship, and appraisal. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34(3):294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim Y, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL. Effects of psychological distress on quality of life of adult daughters and their mothers with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17(11):1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ussher JM, Perz J. Gender differences in self-silencing and psychological distress in informal cancer carers. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34(2):228–242. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitzell A, Pakenham KI. Application of a stress and coping model to positive and negative adjustment outcomes in colorectal cancer caregiving. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(11):1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pikler VI, Brown C. Cancer patients’ and partners’ psychological distress and quality of life: influence of gender role. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2010;28(1):43–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldzweig G, Hubert A, Walach N, Brenner B, Perry S, Andritsch E, et al. Gender and psychological distress among middle-and older-aged colorectal cancer patients and their spouses: an unexpected outcome. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2009;70(1):71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baider L, Ever-Hadani P, Goldzweig G, Wygoda MR, Peretz T. Is perceived family support a relevant variable in psychological distress?: A sample of prostate and breast cancer couples. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2003;55(5):453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldzweig G, Andritsch E, Hubert A, Brenner B, Walach N, Perry S, et al. Psychological distress among male patients and male spouses: what do oncologists need to know? Annals of oncology. 2009;21(4):877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ezer H, Chachamovich JLR, Chachamovich E. Do men and their wives see it the same way? Congruence within couples during the first year of prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(2):155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]