Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: autoreactivity, B cells, cerebral autoregulation, cytotoxic T cells, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, helper T cells

Abstract

Objectives:

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation provides short-term cardiopulmonary life support, but is associated with peripheral innate inflammation, disruptions in cerebral autoregulation, and acquired brain injury. We tested the hypothesis that extracorporeal membrane oxygenation also induces CNS-directed adaptive immune responses which may exacerbate extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-associated brain injury.

Design:

A single center prospective observational study.

Setting:

Pediatric and cardiac ICUs at a single tertiary care, academic center.

Patients:

Twenty pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients (0–14 yr; 13 females, 7 males) and five nonextracorporeal membrane oxygenation Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction score matched patients

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Venous blood samples were collected from the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit at day 1 (10–23 hr), day 3, and day 7 of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Flow cytometry quantified circulating innate and adaptive immune cells, and CNS-directed autoreactivity was detected using an in vitro recall response assay. Disruption of cerebral autoregulation was determined using continuous bedside near-infrared spectroscopy and acquired brain injury confirmed by MRI. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients with acquired brain injury (n = 9) presented with a 10-fold increase in interleukin-8 over extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients without brain injury (p < 0.01). Furthermore, brain injury within extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients potentiated an inflammatory phenotype in adaptive immune cells and selective autoreactivity to brain peptides in circulating B cell and cytotoxic T cell populations. Correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between adaptive immune responses of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients with acquired brain injury and loss of cerebral autoregulation.

Conclusions:

We show that pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients with acquired brain injury exhibit an induction of pro-inflammatory cell signaling, a robust activation of adaptive immune cells, and CNS-targeting adaptive immune responses. As these patients experience developmental delays for years after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, it is critical to identify and characterize adaptive immune cell mechanisms that target the developing CNS.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a complex technique that provides life support during severe respiratory and/or cardiac failure (1). The expanded use of ECMO in pediatric patients reveals a number of complications, including an acute induction of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), long-term neurodevelopmental deficits, and an increasing number of children exhibiting neurologic morbidities (1, 2). In fact, acquired neurologic injury is a significant risk factor, secondary to detrimental mechanisms associated with the underlying disease that contributes to both morbidity and mortality in patients on ECMO (3).

ECMO circuits expose blood to artificial surfaces and activate the coagulation and complement systems (4). This can induce a robust innate (i.e., primary) immune response, that is, similar to SIRS (5). Additionally, ECMO increases the production of interleukin (IL)–1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-α within hours of initiation (5). Complement and pro-inflammatory cytokines activate neutrophils and promote migration into target organs (e.g., lungs) which further exacerbate pathology (6, 7). Similarly, monocytes are also activated by ECMO, although their activation rate is much slower (8). The contribution of adaptive immunity during ECMO neuropathology, however, remains unstudied despite the contribution of adaptive immune mechanisms to similar inflammatory neurologic diseases (9). ECMO promotes cytokine production and precipitates disruptions in cerebral blood flow (CBF) which facilitate CNS antigen release into the periphery—both necessary steps to CNS-directed adaptive immunity. Thus, the primary objective of this pilot study is to test the hypothesis that ECMO initiates CNS-targeting adaptive immunity that may contribute to long-term ECMO-induced neurologic injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Subjects

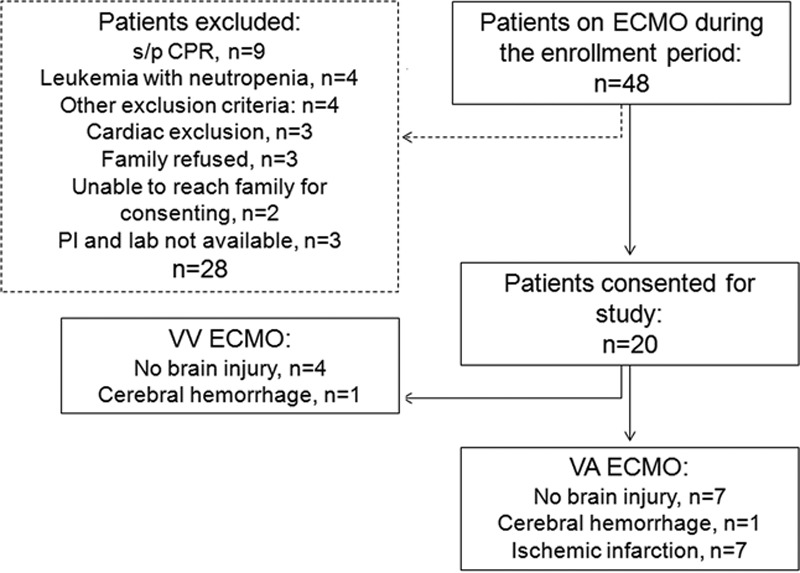

This is a prospective pilot observational study in patients (0–18 yr old) who underwent venoarterial and venovenous ECMO in pediatric and cardiac ICUs at Children’s Health (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238; exclusions are shown in Fig. 1). The study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Healthy control plasma samples were obtained from volunteers (STU122013-036). Sick control patients who were Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD) score matched were also enrolled (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). Demographic, clinical, laboratory, imaging, and outcome data were obtained from the medical chart for each subject. Routine brain MRI was done for most patients after ECMO. Brain injury was defined as abnormal brain MRI findings with or without clinical correlation, as determined by a licensed neuroradiologist, with images as standard of care and not specifically collected for this project. All patients were placed on Rotaflow centrifugal pumps, cannulation for venoarterial was through carotid artery and internal jugular vein and for venovenous through double lumen cannulas placed in the right internal jugular vein. Heparin was the anticoagulation of choice. All patients were sedated with fentanyl and versed, and dexmedetomidine was used as an adjunct in some patients.

Figure 1.

Enrollment diagram. This diagram shows all enrollment for this pilot study, including status/post (s/p) exclusion criteria. Patient recruitment was determined a prior to be completed after 20 patients. CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, PI = principal investigator, VA = venoarterial, VV = venovenous.

Study Design

At the bedside, cerebral autoregulation measurements were collected over the course of ECMO. Bedside blood draws were collected on day 1 (within 10–23 hr of cannulation), day 3, and day 7 of ECMO. Blood was processed for an immediate leukocyte survey by flow cytometry (gating shown in Supplemental Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). Plasma and immune cells were additionally banked for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and autoimmune assay, with all time points of each patient assayed concurrently.

For detailed methodologies pertaining to peripheral blood mononuclear cells flow cytometry, carboxyfluoresceine succinimidyl ester proliferation assay, ELISA, adaptive immune modulation, cerebral autoregulation, and neuroimaging methods (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238).

Statistics

The data obtained were assumed to be nonparametric and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). Kruskal-Wallis with uncorrected Dunn multiple comparisons test, two-way analysis of variance with Fisher Least Significant Difference multiple comparison, Kolmogorov-Smirnov rank-sum test for organ dysfunction, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare data by day and between cohorts. All tests were two-tailed, and significance was set as p value of less than 0.05. Values presented in text are mean ± sd. Spearman correlation analysis was used to correlate autoregulation and neuroimaging scores with absolute cell counts and cytokines. This study was not adequately powered for venoarterial ECMO subgroup analyses alone. One patient on day 1 and another on day 3 were identified as outliers and excluded from the atypical lymphocyte differential analysis.

RESULTS

ECMO Patient Cohort

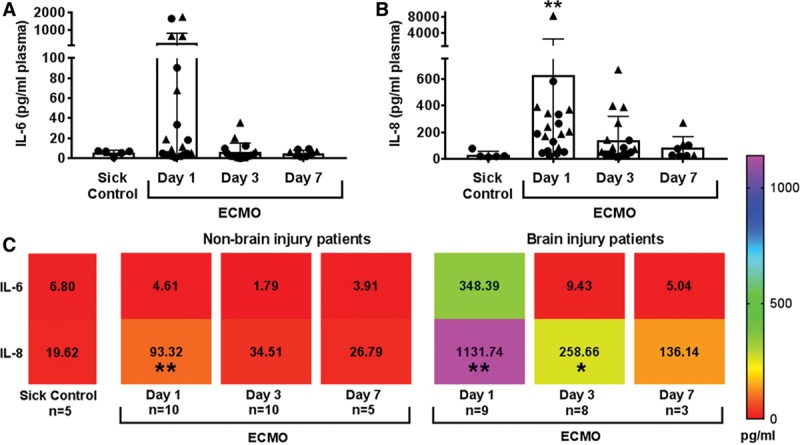

Within the ECMO patient cohort, three patients had a clinical change in neurologic examination, and an additional five patients had neurologic injury identified by standard-of-care post-ECMO MRI (Fig. 1; and Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). An additional patient presented with infarcts prior to placement on ECMO. Together, these patients were identified as “acquired brain injury” patients. Three patients with white matter injury related to prematurity, and an additional eight patients without neurologic deficits and/or neuroimaging abnormalities, were identified as “no brain injury.” There was no difference in the partial thromboplastin time goals or heparin infusion in U/kg/d between patients with and without brain injury (Supplemental Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238), although patients with brain injury presented with lower anti-Xa levels and received more platelets (Supplemental Fig. 1, C and D, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). There was also no difference in severity of organ dysfunction (kidney and liver) between ECMO cohorts (blood urea nitrogen, creatine, aspartate amino transferase, alanine amino transferase, and alkaline phosphatase). For all ECMO patients (n = 20), we observed acute increases in plasma IL-6 and IL-8 (p < 0.01) compared with disease-only patients (n = 5) (Fig. 2, A and B), in accordance with previous results (5). Grouped analyses using flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238) revealed a trend toward an increase of peripheral CD4 T cell cellularity on day 3 of ECMO (p = 0.06) (Supplemental Fig. 3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238) compared with sick controls, as the only adaptive immune response. Concomitant analyses of innate cellularity revealed minimal elevation of innate cell subsets in grouped ECMO-treated patients versus sick control patients. Finally, we analyzed differential counts taken as standard-of-care diagnostics, including pre-ECMO counts not available for the flow cytometry analysis (Supplemental Fig. 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). For neutrophil, lymphocyte, atypical lymphocyte, and monocyte counts, only monocytes were elevated on day 3 compared with all other days (Supplemental Fig. 4D, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238).

Figure 2.

Cytokine levels are elevated in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) patients with acquired brain injury. ECMO induces early cytokine up-regulation for (A) interleukin (IL)–6 and (B) IL-8 at day 1 of ECMO (n = 20) compared with disease-control patients without ECMO (n = 5). Circle shapes are nonbrain injury patients, and triangles represent brain injury patients. C, Heat map representation of all mean ± sd values (text shown, pg/mL) of cytokines separated by brain injury status. Significance is defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance versus sick control shown in the far left column of the heat map.

Plasma From ECMO/Brain-Injured Patients Drives Healthy Adaptive Immune Cells Toward a Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype

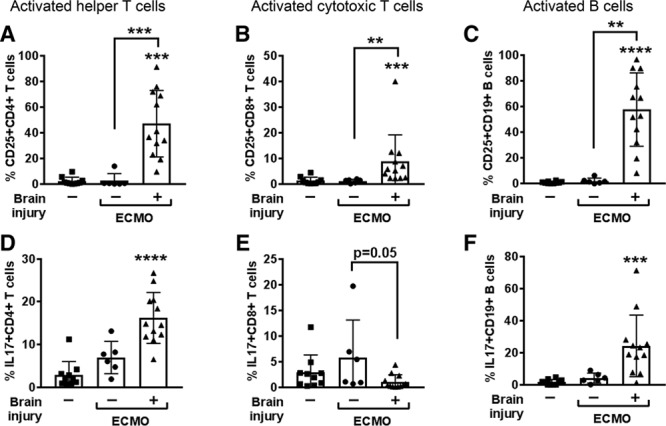

When segregating patients according to the presence of brain injury (Fig. 2C), the brain injury group exhibited greater elevations in pro-inflammatory IL-6 on day 1 of ECMO (p < 0.01 vs sick control). The greatest response, however, came from the neutrophil chemotactic factor IL-8, which increased over 10-fold in brain-injured ECMO patients (p < 0.01 vs sick control) and continued to be elevated on day 3 (p < 0.05 vs sick control) and day 7 of ECMO. IL-8 promotes adaptive T helper (Th) cell recruitment and activation of neutrophils, which further drives the induction of pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells (10). We used peripheral plasma to indirectly ascertain induction of inflammatory adaptive immune cells and found that plasma from ECMO brain-injured patients activated helper (p < 0.001) and cytotoxic (p < 0.01) T cells and B cells (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3; and Supplemental Fig. 5, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238) compared with activation by plasma collected from ECMO patients without brain injury or sick patient controls. Brain-injured ECMO-derived plasma also drove increased production of IL-17 in helper T cells (p < 0.0001) and B cells (p < 0.001), with a concomitant loss in IL-17-producing cytotoxic T cells in brain injury co-cultures relative to nonbrain injury (p = 0.05), an interesting phenomenon that requires further investigation. Only B cells increased interferon (IFN)–γ production with brain-injured plasma (p < 0.001) (Supplemental Fig. 5D, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). These data suggest that patients on ECMO and experiencing brain injury possess an environment within their circulation that is conducive to initiating an activated, pro-inflammatory adaptive immune response.

Figure 3.

Plasma from brain-injured patients supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) drives healthy adaptive immune cells toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Black bar graphs show nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance results for triplicate experiments for activation status (CD25+, n = 6) of (A) CD4+ helper T cells, (B) CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and (C) CD19+ B cells after exposure to healthy plasma-containing media (left columns, squares, n = 5), or ECMO patient-derived plasma-containing media from patients without brain injury (middle columns, circles, n = 2), or with brain injury (right columns, triangles, n = 4). Permutations of test conditions resulted in 10 test conditions for control plasma, six for nonbrain injury ECMO, and 13 for brain injury ECMO. Plasma from ECMO patients with brain injury also elevated intracellular interleukin (IL)–17 production in (D) helper T cells and (F) B cells, but not (E) cytotoxic T cells. Values are mean ± sd and significance between groups on an individual day is shown as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 versus healthy plasma unless otherwise indicated by brackets.

Noncanonical Inflammatory Immune Cells Are Elevated in ECMO/Brain Injury Patients

Surprisingly, during our leukocyte survey, we came across adaptive immune cells that did not express cardinal adaptive immune cell markers. Rarely described, T cells expressing CD161+ produce IL-17 and are postulated to contribute to immune-mediated neurologic diseases (11). Grouped ECMO patients exhibited a decrease in cellularity of activated (i.e., CD161+) helper T cells at day 1 (p < 0.05) and day 3 (p < 0.05) of ECMO (Supplemental Fig. 6, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238) compared with sick controls. These populations were, however, elevated in ECMO patients with brain injury, including activated B cells (day 1; p < 0.05), natural killer T cells (day 3; p < 0.05 and day 7; p < 0.001) and cytotoxic T cells (day 7; p < 0.05) compared with ECMO patients without brain injury (Supplemental Fig. 7, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). These patients with brain injury had concomitant elevations in activated macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 7F, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238) across the full course of ECMO. This shows that in patients presenting with acquired brain injury there is an increase in highly inflammatory circulating adaptive immune populations not identified in standard-of-care immune cell differential counts (Supplemental Fig. 4 E–H, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238).

ECMO/Brain Injury Coincides With Increased CNS-Specific Autoreactive Cytotoxic T Cells

CNS antigen presentation to, and subsequent activation of, adaptive immune cells can lead to the induction of CNS-targeting adaptive immune responses (12–15), with these autoreactive adaptive immune responses sufficiently capable of inducing brain injury, as seen in other CNS diseases (15, 16). Thus, we determined if ECMO-treated patients exhibited adaptive immune cell responses that target CNS-specific peptides, including myelin and neuronal peptides (Supplemental Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238) (12, 13, 15). All responses were compared with an unstimulated sample response to control for the underlying generalized inflammatory disease state unique to each patient (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). We used banked samples from sick PELOD-matched control patients (n = 4), ECMO patients without brain injury (n = 9), and ECMO patients that presented with acquired brain injury (n = 7).

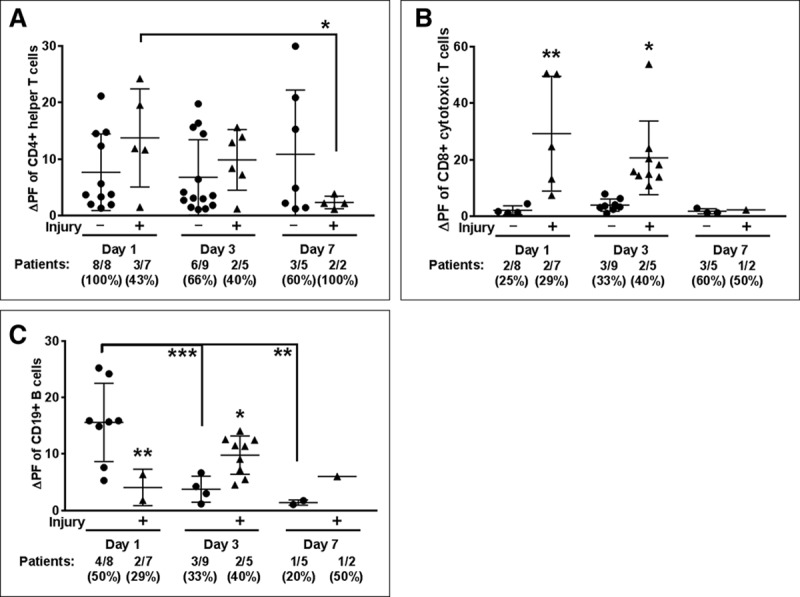

CNS-targeted autoreactivity in helper T cells was similar in magnitude between all cohorts (Fig. 4; and Supplemental Fig. 8, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238), although fewer patients with brain injury had autoreactive cells (three out of seven patients, day 1 of ECMO) compared with the non brain-injured ECMO cohort (eight out of eight patients) (Fig. 4A). The magnitude of helper T cell autoreactivity significantly diminished in the brain-injured cohort over the course of ECMO (day 1 vs day 7; p < 0.05), although day 7 is limited in patient sample size, with only two patients in the acquired brain injury cohort. In contrast, the magnitude of autoreactivity for cytotoxic T cells in ECMO patients peaked at day 3 (p < 0.05 vs days 1 and 7) (Supplemental Fig. 7D, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238), with a consistently higher magnitude of autoreactivity in the brain-injured ECMO patients on both day 1 (p < 0.01) and day 3 (p < 0.05) of ECMO (Fig. 4B). Autoimmune responses for cytotoxic T cells were not detectable at day 7 of ECMO. The cytotoxic T cell responses to both myelin and neuronal peptides were driven by a smaller subset of patients (~25–40% of patients), which was different from the helper T cell response that often included autoreactivity in 60–100% of the patients tested.

Figure 4.

Brain injury associated with cytotoxic T cell autoreactivity to CNS antigens. Autoreactivity data separated by brain injury were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance, Fisher Least Significant Difference. Positive responses (change in proliferation fraction [ΔPF]) from all patients tested (#/#) and corresponding % indicated below graph. A, CD4 helper T cell responses did not differ between extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) patients without brain injury (circles) and those with brain injury (triangles). B, Autoreactive CD8 T cell responses were, however, more abundant in brain injury ECMO patients, and (C) B cell autoreactivity was increased ECMO patients without brain injury at day 1, which was reversed by day 3 as brain-injured ECMO patients exhibited increased autoreactivity. Significance between groups on an individual day is shown as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 or between groups, as indicated by brackets.

B cell autoreactivity was also much higher in the ECMO-treated patients over sick control patients (Supplemental Fig. 8F, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). When analyzed based on brain injury status, B cell autoreactivity to CNS antigens is unique on day 1 of ECMO, as it is significantly elevated in the ECMO patients without brain injury (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4C). For the ECMO patients without brain injury, this early and high level of CNS-directed autoreactivity significantly diminished at both day 3 (p < 0.001 vs day 1) and day 7 (p < 0.01 vs day 1) of ECMO. In contrast, ECMO patients with brain injury exhibited a delayed increase in autoreactivity on day 3 (p < 0.05). Although half of the ECMO patients (4/8) without brain injury exhibited autoreactivity to myelin and neuronal peptides on day 1, the day 3 response in the brain injury cohort overall was driven by the response in two patients. In summary, ECMO treatment coincided with autoreactivity to CNS-specific antigens in cytotoxic T cell and B cells.

Disrupted Cerebral Autoregulation Correlates With Adaptive Immune Responses for ECMO Patients With Brain Injury

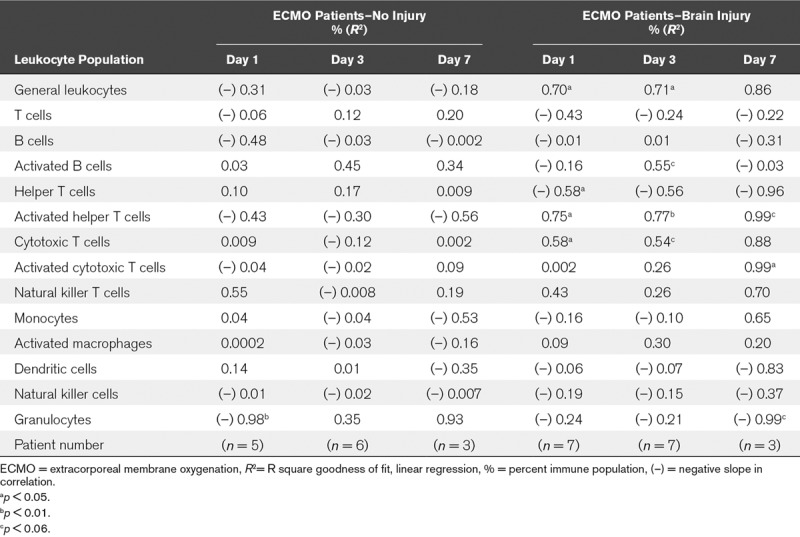

Pediatric patients on ECMO exhibit disturbances in cerebral autoregulation (17), which is the brain’s ability to maintain constant CBF despite changes in systemic blood pressure (18). Continuous near-infrared spectroscopy bedside monitoring can identify disrupted cerebral autoregulation for several diseases associated with secondary neurologic injury, including ECMO (17, 19, 20). In our patient population, 13 patients were simultaneously enrolled in an observational study to monitor cerebral autoregulation over the course of ECMO, including six ECMO patients without brain injury, and seven with acquired brain injury. Taking the value for disrupted cerebral autoregulation for the duration of ECMO, we determined correlations between disrupted cerebral autoregulation and circulating immune cells (Supplemental Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/E238). Only the percentage of activated helper T cells consistently correlated with disrupted cerebral autoregulation over the course of ECMO. Once data were parsed between ECMO patients with and without brain injury (Table 1), the majority of significant correlations between adaptive immune cell subsets and disruptions in cerebral autoregulation were driven by the brain-injured ECMO patients. This shows that patients who exhibit disruptions in cerebral autoregulation experience concomitant activation of the adaptive immune system.

TABLE 1.

Correlation of Adaptive Immune Responses to Disruption of Cerebral Autoregulation While on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

DISCUSSION

ECMO is a complex technique used in cases where trauma, sepsis, congenital heart disease, or respiratory failure necessitates cardiopulmonary support. There has been a steady increase in pediatric ECMO usage (21, 22), but secondary complications increase morbidity and mortality and include ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, and seizures (23–25). For the first time, we show in this pilot study that pediatric ECMO results in the loss of cerebral autoregulation concomitant with a robust mobilization and activation of adaptive immune cells, detection of CNS-targeting adaptive immune responses, and induction of pro-inflammatory cell signaling predominantly in patients that present with acquired brain injury. We previously reported that acquired brain injuries could be predicted by loss of cerebral autoregulation in pediatric ECMO patients (17). What is critical to consider is that as cerebral autoregulation is disrupted, the blood flow in the brain is no longer constant but fluctuates similar to the systemic circulation. Subsequent higher shear stress at the capillaries could disrupt the blood-brain barrier, whereas lower shear stress within the venules could increase the ability of circulating leukocytes to diapedese into the parenchyma (26, 27). This is particularly relevant for patients with high levels of circulating IL-8, which induces the firm adherence of immune cells to the endothelial vessel walls (28). Increased leukocyte diapedesis under the low-flow would bring inflammatory (Fig. 2), activated (Fig. 3), and autoreactive (Fig. 4) adaptive immune cells into contact with the brain parenchyma, a necessary step to further promote brain injury.

We observed a distinct cytotoxic T cell response in ECMO patients with brain injury at days 1 and 3 of ECMO, with CNS autoreactivity to myelin and neuronal peptides. These data are highly suggestive that cytotoxic T cells are being mobilized by the brain injury and not by the underlying disease, and increased T cell egress may be reflected in lower circulating T cell populations. In fact, the CNS targeting by these cells is reminiscent of similar cells found in Rasmussen’s Encephalitis, multiple sclerosis (MS), and the murine model of MS, which have all implicated inflammatory CNS-specific cytotoxic T cells as mediators of neuropathology (29). This is understandable, as the inflammatory nature of these cells would allow CNS access, whereas their antigen-specificity would allow them to target CNS resident cells (30). More in-depth experiments are required to ascertain the role of ECMO-induced autoreactive cytotoxic T cells, whose pathology may not ultimately be limited to the duration of ECMO or the underlying disease, but could affect neurodevelopment with long-lasting detrimental outcomes (3).

Surprisingly, we also detected a high number of CNS-specific B cells in the nonbrain injured group on day 1 of ECMO. This phenomenon declined by day 3, just as autoreactive responses of B cells in brain-injured patients increased. Autoreactivity by B cells contributes to several neurologic diseases (14, 31, 32), with development of autoreactive CNS-specific B cells considered extremely dangerous, as these cells are capable of 1) producing antibodies which target CNS resident cells (33) and 2) generating de novo secondary lymphoid tissue within the CNS (34). Thus, it was very surprising those ECMO patients without brain injury exhibited a robust CNS-directed B cell autoreactivity. Although highly speculative, it is possible that some self-reactive adaptive immune cells play a neuroprotective or neuroreparative role after brain injury. In fact, peripheral antigen presentation of neuronal antigens in stroke patients correlates to improved long-term recovery (35). Thus, we are mindful of the potential for CNS autoreactivity-mediated neuroprotection and will dissect the role for each of these autoreactive cells in future studies.

Before this study, there have been several drugs which target inflammation, including glucocorticoids, and other immune-modulatory agents, with the goal of altering the inflammatory response preoperatively to prevent brain injury. Although these drugs have been successfully used in preclinical studies, clinical trials identified certain inadequacies of global immune suppression in providing neuroprotection (36, 37). In pediatric patients, altered CBF and induction of systemic inflammation may be key mechanisms of brain injury, whereas inflammatory mediators stemming from the adaptive system, either cellular (T and B cells) or cytokines (IL-8, IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-17) can be neurotoxic to the developing brain. Now, with the findings of this study, we believe that a focused suppression of the adaptive immune system using pharmacologic agents approved in other CNS diseases may have a potential neuroprotective role for ECMO patients at risk of acquired brain injury (38).

This study had several limitations, including small patient enrollment and cerebral autoregulation measurements that spanned the course of ECMO and not the specific times of blood draw. We also recognize that the PELOD-matched control patients were not as sick as patients placed on ECMO. Future studies should determine the long-term effects of systemic inflammation, including cytokine production, loss of autoregulation, persistent CNS-directed autoreactivity, and their cumulative associations with neurocognitive and other developmental delays in this patient population. In addition, in order to elucidate the mechanisms involved in the ECMO-induced neuro-immunological interactions, it must be determined if ECMO-activated adaptive immune cells can directly target CNS resident cells.

CONCLUSIONS

This small observational study highlights a previously uncharacterized association between disruptions in cerebral autoregulation, either preceding or concomitant to neuroimmune responses that may contribute to brain injury for pediatric ECMO patients. As these patients experience developmental delays for years after ECMO, it is critical to identify the role of neuroinflammatory adaptive immune cell mechanisms that target the developing CNS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jefferson Tweed, MS, for collecting revision-related data from the medical record.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Drs. Ortega, Pandiyan, Raman, and Stowe contributed equally.

Drs. Ortega and Pandiyan designed, performed, and analyzed the immunology-based assays and co-wrote the article. Dr. Pandiyan performed and analyzed the immunology-based assays as well as recruited patients and co-wrote the article. Ms. Windsor and Dr. Lee recruited patients and Ms. Windsor, Ms. Torres, Ms. Selvaraj, and Dr. Stowe processed samples. Dr. Tian quantified autoregulation disruption based on wavelength transform coherence. Dr. Morriss scored all neuroimaging. Drs. Raman and Stowe designed and supervised the study and co-wrote the article. All authors read, edited, and approved of the article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Drs. Tian and Raman were supported, in part by, American Heart Association (AHA) Beginning-Grant-in Aid (15BGIA25860045). Drs. Pandiyan and Raman were funded by Extracorporeal Life Support Organization research grant and UT Southwestern Center for Translational Medicine award. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR001105. Dr. Stowe was supported from the AHA (14SDG 18410020), National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS088555), Dr. Ortega (14POST20480373) and Ms. Selvaraj (17PRE33660147) from the AHA.

Drs. Ortega’s, Pandiyan’s, Windsor’s, and Stowe’s institutions received funding from Extracorporeal Life Support Organization and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number UL1TR001105. Drs. Ortega, Pandiyan, Windsor, Torres, Raman, and Stowe received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Tian’s institution received funding from the American Heart Association, and he disclosed work for hire. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robinson S, Peek G. The role of ECMO in neonatal & paediatric patients - ScienceDirect. Paediatr Child Health 2015; 25:222–227. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madderom MJ, Reuser JJ, Utens EM, et al. Neurodevelopmental, educational and behavioral outcome at 8 years after neonatal ECMO: A nationwide multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39:1584–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown KL, MacLaren G, Marino BS. Looking beyond survival rates: Neurological outcomes after extracorporeal life support. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39:1870–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malfertheiner MV, Philipp A, Lubnow M, et al. Hemostatic changes during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A prospective randomized clinical trial comparing three different extracorporeal membrane oxygenation systems. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McILwain RB, Timpa JG, Kurundkar AR, et al. Plasma concentrations of inflammatory cytokines rise rapidly during ECMO-related SIRS due to the release of preformed stores in the intestine. Lab Invest 2010; 90:128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plötz FB, van Oeveren W, Bartlett RH, et al. Blood activation during neonatal extracorporeal life support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993; 105:823–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortenberry JD, Bhardwaj V, Niemer P, et al. Neutrophil and cytokine activation with neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr 1996; 128:670–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graulich J, Walzog B, Marcinkowski M, et al. Leukocyte and endothelial activation in a laboratory model of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Pediatr Res 2000; 48:679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQualter JL, Bernard CC. Multiple sclerosis: A battle between destruction and repair. J Neurochem 2007; 100:295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelletier M, Maggi L, Micheletti A, et al. Evidence for a cross-talk between human neutrophils and Th17 cells. Blood 2010; 115:335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Annibali V, Ristori G, Angelini DF, et al. CD161(high)CD8+T cells bear pathogenetic potential in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2011; 134(pt 2):542–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortega SB, Kong X, Venkataraman R, et al. Perinatal chronic hypoxia induces cortical inflammation, hypomyelination, and peripheral myelin-specific T cell autoreactivity. J Leukoc Biol 2016; 99:21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega SB, Noorbhai I, Poinsatte K, et al. Stroke induces a rapid adaptive autoimmune response to novel neuronal antigens. Discov Med 2015; 19:381–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stowe AM, Ireland SJ, Ortega SB, et al. Adaptive lymphocyte profiles correlate to brain Aβ burden in patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Neuroinflammation 2017; 14:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.York NR, Mendoza JP, Ortega SB, et al. Immune regulatory CNS-reactive CD8+T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Autoimmun 2010; 35:33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huseby ES, Huseby PG, Shah S, et al. Pathogenic CD8 T cells in multiple sclerosis and its experimental models. Front Immunol 2012; 3:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian F, Morriss MC, Chalak L, et al. Impairment of cerebral autoregulation in pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation associated with neuroimaging abnormalities. Neurophotonics 2017; 4:041410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strandgaard S, Paulson OB. Cerebral autoregulation. Stroke 1984; 15:413–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalak LF, Tian F, Adams-Huet B, et al. Novel wavelet real time analysis of neurovascular coupling in neonatal encephalopathy. Sci Rep 2017; 7:45958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian F, Tarumi T, Liu H, et al. Wavelet coherence analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neuroimage Clin 2016; 11:124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy FH, McDermott KM, Kini V, et al. Trends in U.S. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use and outcomes: 2002–2012. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015; 27:81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karamlou T, Vafaeezadeh M, Parrish AM, et al. Increased extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center case volume is associated with improved extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival among pediatric patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145:470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett CS, Bratton SL, Salvin JW, et al. Neurological injury after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use to aid pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2009; 10:445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luyt CE, Bréchot N, Demondion P, et al. Brain injury during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42:897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polito A, Barrett CS, Rycus PT, et al. Neurologic injury in neonates with congenital heart disease during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: An analysis of extracorporeal life support organization registry data. ASAIO J 2015; 61:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyduk SJ, Cybulsky MI. Role of alpha4beta1 integrins in chemokine-induced monocyte arrest under conditions of shear stress. Microcirculation 2009; 16:17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith LA, Aranda-Espinoza H, Haun JB, et al. Interplay between shear stress and adhesion on neutrophil locomotion. Biophys J 2007; 92:632–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerszten RE, Garcia-Zepeda EA, Lim YC, et al. MCP-1 and IL-8 trigger firm adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelium under flow conditions. Nature 1999; 398:718–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilli D, Zou A, Tea F, et al. Expanding role of T cells in human autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system. Front Immunol 2017; 8:652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauer BM, Schmalstieg WF, Howe CL. Axons are injured by antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells through a MHC class I- and granzyme B-dependent mechanism. Neurobiol Dis 2013; 59:194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyle KP, Quach LN, Solé M, et al. B-lymphocyte-mediated delayed cognitive impairment following stroke. J Neurosci 2015; 35:2133–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Hernandez E, Horvath J, Shiloh-Malawsky Y, et al. Analysis of complement and plasma cells in the brain of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurology 2011; 77:589–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisak RP, Nedelkoska L, Benjamins JA, et al. B cells from patients with multiple sclerosis induce cell death via apoptosis in neurons in vitro. J Neuroimmunol 2017; 309:88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serafini B, Rosicarelli B, Magliozzi R, et al. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol 2004; 14:164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Planas AM, Gómez-Choco M, Urra X, et al. Brain-derived antigens in lymphoid tissue of patients with acute stroke. J Immunol 2012; 188:2156–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werdelin L, Boysen G, Jensen TS, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 1990; 82:132–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filippini G, Del Giovane C, Vacchi L, et al. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for multiple sclerosis: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (6):CD008933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gajofatto A, Turatti M, Monaco S, et al. Clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability of fingolimod for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2015; 7:157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]