In PNAS, Li et al. (1) recently reported analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis ribosomes formed under zinc-limited conditions. A zinc chelator [N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine] was added to growth medium and an extended purification procedure was employed to obtain zinc-depleted (C−) ribosomes for cryo-EM. The structure was solved at 3.5-Å resolution and showed five partially modeled C− ribosomal proteins in place of their zinc-binding (C+) paralogs. Additionally, a hibernation-promoting factor, MSMEG_1878 [designated by Li et al. as a mycobacterial protein Y (MPY)], associated with ribosomes at the coding region of the 30S subunit, resulting in ribosome inactivation and tolerance to aminoglycosides. While this work contributes toward understanding of ribosome hibernation in mycobacteria, we believe that differences in growth conditions used to stimulate production of C+ and C− ribosomes led the authors to erroneously conclude that MPY exclusively binds to C− ribosomes. Here, we present our data and refer to work by others to offer an alternative interpretation of the results.

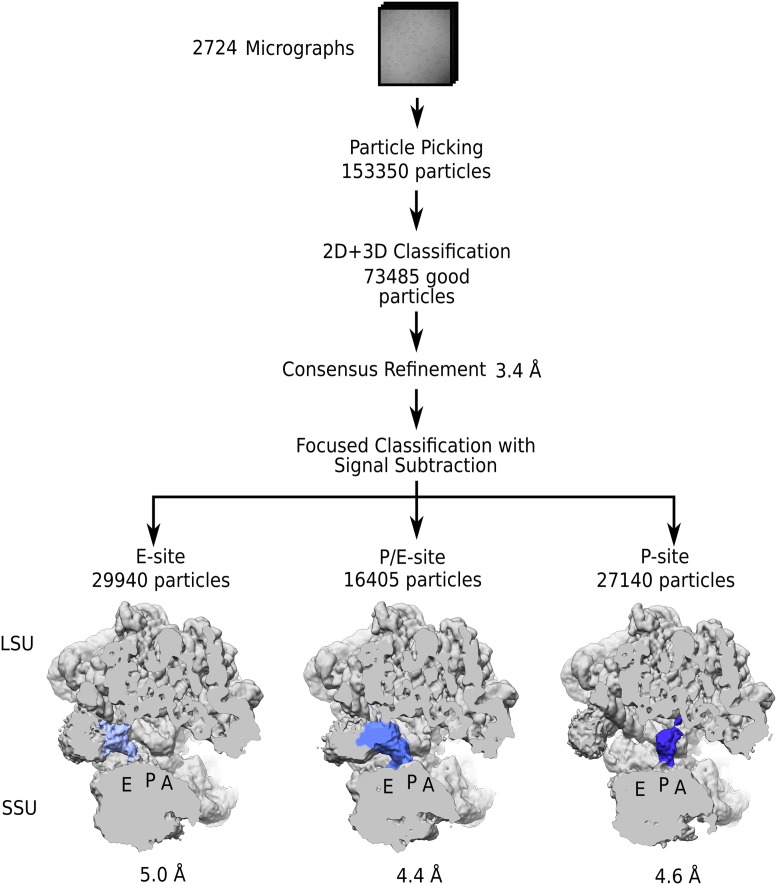

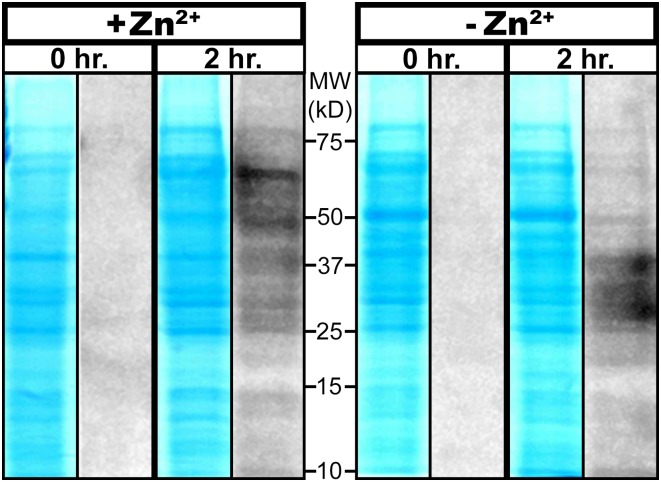

We used a previously optimized protocol for gradual zinc depletion to allow analysis of actively growing M. smegmatis that employs C− ribosomes (2). We refer to C− as alternative (Alt) ribosomes and C+ as primary (Prim) ribosomes (2, 3). Cell-free supernatants of M. smegmatis were grown to late-log phase in chemically defined Sauton’s medium without addition of Zn2+, and Alt ribosomes were purified in a single 4-h sucrose cushion step and subjected to cryo-EM. A total of 73,485 particles yielded an overall 3.4-Å-resolution reconstruction of the Alt ribosome. Upon masked classification with signal subtraction, functional states were identified with natively preserved tRNAs at 4.4- to 5.0-Å resolution, whereas no binding of MPY was detected, thus indicating the translational activity of Alt ribosomes at the time of purification (Fig. 1). In agreement with these data, a biochemical assay indicated that Prim and Alt ribosomes have comparable overall translational activities (Fig. 2). Finally, there was no apparent difference in resistance to kanamycin and streptomycin for cultures grown in zinc-limited vs. zinc-replete medium, nor did deletion of Alt ribosomal proteins have any effect on susceptibility to these antibiotics. Therefore, our data suggest that when zinc is scarce, M. smegmatis employs Alt ribosomes for translation during active growth, and there is no evidence for their specific role in hibernation or aminoglycoside resistance.

Fig. 1.

Cryo-EM reconstruction of M. smegmatis Alt (C−) ribosomes. The structure was solved to an overall 3.4-Å resolution using 73,485 particles. To identify bound ligands, we performed classification employing signal subtraction on tRNA binding sites A, P, and E shared by the large (LSU) and small (SSU) ribosomal subunits, which resulted in three distinct classes containing tRNAs (colored).

Fig. 2.

Translational activity of M. smegmatis containing Prim (C+) or Alt (C−) ribosomes. Cells were grown to late-log phase, either supplemented with 6 µM Zn2+ to generate actively growing bacteria with Prim (C+) ribosomes, or with Zn2+ omitted from growth medium to generate actively growing bacteria with Alt (C−) ribosomes (2). The cultures containing Prim or Alt ribosomes (+Zn2+ or −Zn2+, respectively) were then used in a pulse-chase experiment to demonstrate translational activities of Prim and Alt ribosomes. SDS/PAGE from the pulse-chase experiment shows total protein (blue) and nascent protein synthesis (grayscale) as detected by incorporation of amino acid analog l-azidohomoalanine (AHA) into proteins, which are then labeled with tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) using Click-iT chemistry (Invitrogen). Aliquots were removed immediately (0 h) and 2 h after addition of AHA, total proteins were extracted with TRIzol as previously described (3), and a 50-ng portion was labeled with TAMRA for visualization.

We propose that the binding of MPY and hibernation of Alt (C−) ribosomes reported by Li et al. (1) might have been caused by severe zinc depletion, resulting in growth arrest. In contrast, Prim (C+) ribosomes used for comparison were present in metabolically active zinc-replete bacteria; that is, before stasis and association with MPY. Indeed, biochemical data demonstrated that MPY binds Prim ribosomes to promote hibernation and it has been aptly named ribosome-associated factor under stasis (4), which was not acknowledged by Li et al. In addition, recently published structural data showed that Prim ribosomes bind MPY in the same way as Alt ribosomes do (5). Therefore, it can be concluded that ribosome hibernation caused by MPY is not unique to zinc depletion and is likely to be associated with stress and stationary phase in general, as also previously reported for other organisms (6, 7).

The cryo-EM data of M. smegmatis Alt ribosomes have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under the accession numbers EMD-0276, EMD-0277, EMD-0278, EMD-0284, EMD-0285, and EMD-0286.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Carroni, J. M. de la Rosa Trevin, J. Conrad, and S. Fleischmann for the smooth running of the data collection and processing. The data were collected at the Swedish national cryo-EM facility funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg, Family Erling Persson, and Kempe foundations. This work was supported by the NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R21AI109293 and the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant P30GM114737 (to S.P.) and by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research Grant FFL15:0325, the Ragnar Söderberg Foundation Grant M44/16, the Swedish Research Council Grant NT_2015-04107, and the Cancerfonden Grant CAN 2017/1041 (to A.A.).

Footnotes

References

- 1.Li Y, et al. Zinc depletion induces ribosome hibernation in mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:8191–8196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804555115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dow A, Prisic S. Alternative ribosomal proteins are required for growth and morphogenesis of Mycobacterium smegmatis under zinc limiting conditions. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prisic S, et al. Zinc regulates a switch between primary and alternative S18 ribosomal proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97:263–280. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trauner A, Lougheed KE, Bennett MH, Hingley-Wilson SM, Williams HD. The dormancy regulator DosR controls ribosome stability in hypoxic mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24053–24063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.364851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra S, Ahmed T, Tyagi A, Shi J, Bhushan S. Structures of Mycobacterium smegmatis 70S ribosomes in complex with HPF, tmRNA, and P-tRNA. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13587. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31850-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matzov D, et al. The cryo-EM structure of hibernating 100S ribosome dimer from pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Commun. 2017;8:723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00753-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez Boerema A, et al. Structure of the chloroplast ribosome with chl-RRF and hibernation-promoting factor. Nat Plants. 2018;4:212–217. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]