Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the proportion of potentially relevant undisclosed financial ties between clinical practice guideline writers and pharmaceutical companies.

Design

Cross-sectional study of a stratified random sample of Australian guidelines and writers.

Setting

Guidelines available from Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council guideline database, 2012–2014, stratified across 10 health priority areas.

Population

402 authors of 33 guidelines, including up to four from each area, dependent on availability: arthritis/musculoskeletal (3); asthma (4); cancer (4); cardiovascular (4); diabetes (4); injury (3); kidney/urogenital (4); mental health (4); neurological (1); obesity (1). For guideline writers with no disclosures, or who disclosed no ties, a search of disclosures in the medical literature in the 5 years prior to guideline publication identified potentially relevant ties, undisclosed in guidelines. Guidelines were included if they contained recommendations of medicines, and writers included if developing or writing guidelines.

Main outcome measures

Proportions of guideline writers with potentially relevant undisclosed financial ties to pharmaceutical companies active in the therapeutic area; proportion of guidelines including at least one writer with a potentially relevant undisclosed tie.

Results

344 of 402 writers (86%; 95% CI 82% to 89%) either had no published disclosures (228) or disclosed they had no ties (116). Of the 344 with no disclosed ties, 83 (24%; 95% CI 20% to 29%) had potentially relevant undisclosed ties. Of 33 guidelines, 23 (70%; 95% CI 51% to 84%) included at least one writer with a potentially relevant undisclosed tie. Writers of guidelines developed and funded by governments were less likely to have undisclosed financial ties (8.1%vs30.6%; risk ratio 0.26; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.53; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Almost one in four guideline writers with no disclosed ties may have potentially relevant undisclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies. These data confirm the need for strategies to ensure greater transparency and more independence in relationships between guidelines and industry.

Keywords: conflicts of interest, pharmaceutical industry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study is the largest to date to examine undisclosed ties of guideline writers and includes a broad sample of guidelines across 10 disease categories.

Our study includes guidelines with different funding and development arrangements, enabling comparison of guidelines funded and developed by government, with other guidelines.

Our study did not investigate the undisclosed ties of guideline writers who had disclosed ties in the sample of guidelines analysed.

Study results likely underestimate the extent of undisclosed financial ties of guideline writers.

Introduction

There is global concern about the nature and extent of financial ties between pharmaceutical companies and health professionals, including those who develop influential clinical practice guidelines.1–3 In 2009, a landmark Institute of Medicine report on conflicts of interest acknowledged the importance of collaboration with industry, but warned financial ties to industry were widespread and risked jeopardising the integrity of medical education, research and practice, and called for greater transparency and independence.1 A subsequent Institute of Medicine report, titled ‘Clinical practice guidelines we can trust’, recommended that groups developing guidelines ‘optimally comprise members without conflict of interest.’2 Systematic review evidence suggests most guideline writers disclose some form of industry affiliation, with estimates between 56% and 87%.3 There are, however, few data on the extent of undisclosed financial ties of guideline writers. One study of North American cholesterol and diabetes guidelines estimated 11% of writers had undisclosed ties,4 another study of American head and neck surgery guidelines found 6% had discrepancies between disclosures and an open payments database,5 while a Danish study of 14 specialty society guidelines found 52% had undisclosed ties.6 (For consistency, the term guideline writer is used throughout to refer to those who develop, draft and author guidelines.)

A conflict of interest is defined as “a set of circumstances that creates a risk that professional judgement or actions regarding a primary interest will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest”.1 A primary interest of a guideline writer may be maximising health outcomes, and a secondary interest could be personal gain derived from a financial relationship with a company active in the relevant therapeutic area. Evidence from other areas, such as clinical trials, has shown such conflicts of interest may introduce bias. A recent systematic review found drug trials sponsored by industry more often have efficacy results and conclusions favourable to the sponsor.7 Similarly, a cross-sectional study of randomised trials found those authored by principal investigators with ties to pharmaceutical companies were more likely than other trials to report favourable results.8 Such evidence has provoked debate about the optimum constitution of guideline groups, with calls for chairs and a majority of writers to be free of financial ties,9 10 as well as recommendations for exclusion of any conflicted writer.2

In Australia, the publicly funded National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) is currently engaged in improving standards for guideline development, including in relation to transparency and management of conflicts of interest. An internal analysis of 9 years of Australian guidelines made available via the NHMRC guideline portal, 2005–2013, found only 12% of guidelines published declarations of the conflicts of interest of guideline writers.11 As part of work to improve standards of guidelines which can have direct impacts on how clinicians deliver care to their patients, the NHMRC is developing new ‘guidelines for guidelines’, and a draft released for public comment in 2017 included the recommendation: “Organisations planning guidelines should aim to appoint a guideline development group whose members have no financial or other links with relevant industry groups”.12 In order to inform ongoing efforts to improve guideline quality in Australia and internationally, our objective was to investigate the extent of undisclosed financial ties to industry, for a broad cross-section of guideline writers from different categories of guideline developer, sampled from a comprehensive national guideline database, across a wide spectrum of diseases.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of a stratified random sample of Australian clinical practice guidelines and followed the STROBE checklist for reporting observational studies (see online supplementary file 1).13

bmjopen-2018-025864supp001.pdf (55.8KB, pdf)

Sampling guidelines

We identified a stratified random sample of clinical practice guidelines from within the NHMRC guidelines database, across nine government-designated health priority areas (https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nhmrc-corporate-plan-2017-2018) plus kidney/urogenital, published in the years 2012–2014. The NHMRC database comprised guidelines made available on the publicly accessible NHMRC guidelines portal, which aimed to include all Australian guidelines, defined broadly as published articles making clinical recommendations. While the NHMRC portal at that time included all Australian guidelines, it also provided users of the portal with information on quality indicators for these guidelines, such as whether the guideline was based on a systematic review of evidence, whether the authors provided conflict of interest disclosures and whether or not the guideline had been approved by NHMRC. From 2015, the NHMRC portal restricted the inclusion of guidelines to only include guidelines which met certain quality standards, so to achieve a representative sample from the comprehensive collection of widely used Australian guidelines, we analysed guidelines available on the portal in the 3 years leading up to the change.

In 2017, NHMRC staff (HJ) identified all guidelines in the database, published in the years 2012–2014, and used previous coding by NHMRC to exclude articles not relevant to the 10 health areas of interest, those not considered guidelines, including those coded as Evidence Reviews, Posters/Flowcharts, Standards and Summary guidelines. Following the initial screen, each guideline was randomly ordered using Microsoft Excel within each of the 10 health areas. Two authors (LB, RM) then assessed each guideline in the order they had been ranked, against explicit inclusion criteria, and identified guideline writers to be included in the analysis. Guidelines were included if they were associated with a professional organisation or entity and made mention of medicines in recommendations. They were excluded if they were a journal article unconnected from an external organisation, or if no author names or full text was available. Guideline writers listed in the guideline were included for analysis if they were explicitly engaged in developing, preparing or writing the guideline, and excluded if they were external consultants, members of oversight committees or staff from a drug company, NHMRC or administrative staff. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

The primary unit of analysis was the guideline writer. Based on assumptions that 10% of guideline writers might have an undisclosed relevant financial tie, and that guidelines would have 4–20 writers each, we estimated a need for a minimum sample of 12 guidelines—aiming for approximately 140 writers—to produce a CI of a width of 10% around our estimate of the proportion of writers with undisclosed ties. In addition, to obtain as broad a cross-section as possible, we aimed to analyse up to four guidelines per health priority/disease area, depending on guideline availability.

Guideline and author information

One investigator (either AL or RM) extracted all relevant information from each included guideline into the REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Sydney.14 The extracted information included the names of all included writers, classified in one of three ways: disclosure of ties; disclosure of no ties; no disclosure present. Disclosures were those included in the guideline document or associated publicly available documents. Information on whether the guideline had a statement on conflicts of interest, and the developer/s and funder/s was also extracted.

Identification of potentially relevant undisclosed financial ties

For any guideline writer with no declaration present, or who declared no conflicts of interests, one investigator (AL or RM) conducted a search of the writer’s publications in the 5 years before the year of guideline publication. The period of 5 years was chosen for the following reasons: many guidelines are estimated to be at least 2 years in development before the year of publication; disclosures are directly relevant at the start of the process of guideline development; WHO guidance suggests a period of 4 years prior to publication is relevant when disclosing financial ties15; many disclosure policies have a recall period of 3 to 5 years.16 Publications were also searched in the 3 years following guideline publication, as some organisations, including the Institute of Medicine, recommend guideline writers be free of conflicts for periods of time after guideline publication.17

The Scopus database was used to search for publications of guideline writers using their names and affiliations. Full texts were obtained. Searches were conducted from the earliest date and as per Forsyth et al 18 were stopped once a potentially relevant financial tie was identified. A potentially relevant tie was defined as a financial tie to a pharmaceutical company actively marketing or in late stages of bringing a medicine to market in the therapeutic area relevant to the guideline, at the time of the guideline publication, determined through searches of company websites and relevant product information material. Categorisation of ties was developed based on criteria set by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, ICMJE, and based on adaptations of ICMJE criteria used in a previous study,18 including grants (funding for research study), personal fees (consulting, advisory, speakers, honoraria, travel), patents/copyrights/royalties and miscellaneous. Once a potentially relevant tie was identified by one author (AL or RM), a second author (RM or LB) double checked the full text of the disclosure and verified the tie as a potentially relevant tie, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Searches were conducted between August and December 2017.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

The primary outcome measures were specified as the proportion of guideline writers with potentially relevant undisclosed ties, and the proportion of guidelines in the sample which included at least one writer with an undisclosed tie. Secondary outcome measures were the proportion of writers with disclosed ties, the proportion of guidelines which have any statement about conflicts of interest, and the proportion of guidelines developed and funded by governments (state, federal or territories). We report data proportions using descriptive statistics and including 95% CIs. We examined the association between having statements and the proportion of potentially relevant undisclosed ties of writers, and the association between a guideline being developed and funded by government/s and the proportion of potentially relevant undisclosed ties of writers. Potential associations were tested using the χ2 test. CIs were not adjusted for clustering of writers within multiple guidelines or for clustering of guidelines within disease area.

Ethics

As all publications analysed for this study were on the public record, the chair of Bond University’s Human Research Ethics committee asserted that the study did not require ethics review if no individuals were identified or described.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved in this study.

Results

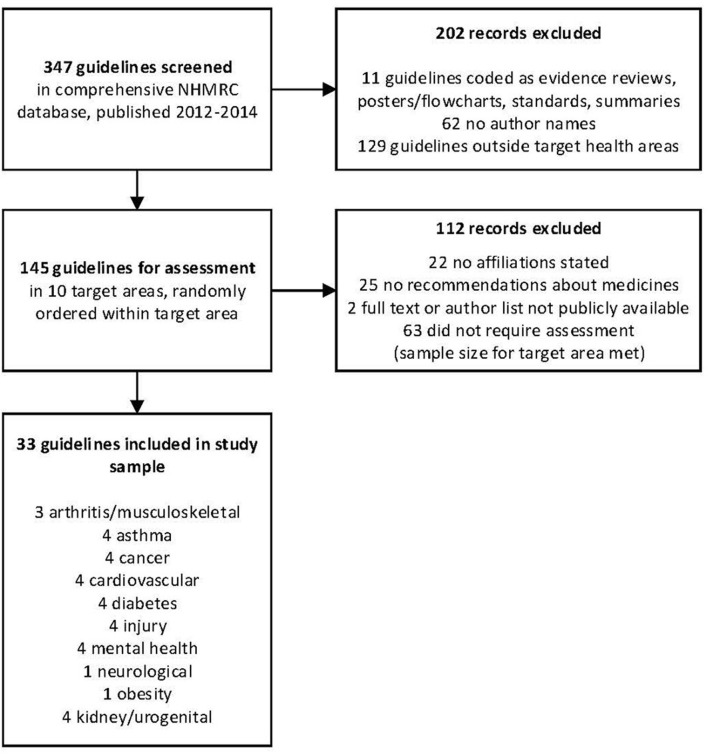

Characteristics of guidelines

There was a total of 347 guidelines in the NHMRC database, published 2012–2014 (figure 1). The initial screen excluded 11 items not considered guidelines, coded by NHMRC as Evidence Reviews, Posters/Flowcharts, Standards and Summary guidelines, 62 because they did not contain names of those who had developed the guideline and 129 published outside the 10 health areas in this study. The remaining 145 guidelines were assigned a random number to establish a random order for assessment of the guidelines within each of the 10 health areas. We continued to assess guidelines within each area in random order until we had included four for each health area or had completed assessing all the available guidelines in a given health area. In total, LB and RM assessed 82 guidelines. Forty-nine of those guidelines were excluded after assessment because they were a publication only with no affiliation to any external organisation (n=22), had no recommendations about medications (n=25), or the full text or author list of the guideline was not publicly available (n=2). Sixty-three were not assessed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for sample. NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council.

We included 33 guidelines in our final sample: arthritis/musculoskeletal (n=3); asthma (n=4); cancer (n=4); cardiovascular (n=4); diabetes (n=4); injury (n=4); mental health (n=4); neurological (n=1); obesity (n=1); kidney/urogenital (n=4) (online supplementary file 2). The 33 guidelines involved a total of 402 guideline writers, with individual guidelines having between 2 and 35 writers included for analysis.

bmjopen-2018-025864supp002.pdf (47.1KB, pdf)

Prevalence of undisclosed ties

Among all 402 guideline writers, 58 disclosed ties (14%; 95% CI 11% to 18%) (table 1). Among the 402 writers, 344 had no disclosed ties (86%; 95% CI 82% to 89%), including 228 writers where no disclosures appeared and 116 writers with statements that they had no ties. Of the 344 writers with no disclosed ties, 83 had at least one potentially relevant undisclosed tie (24%; 95% CI 20% to 29%), discovered in the published literature in the same year as the guideline was published or the previous 5 years. Of those undisclosed ties, the first category of tie listed in the relevant disclosure was pharmaceutical company grant (64%) or personal fees (36%). If the time frame was extended to 3 years after the guideline, the proportion of potentially relevant undisclosed ties rose from 24% to 28% (95% CI 23% to 33%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of guideline writers from a stratified random sample of guidelines, 2012–2014 (n=33)

| Therapeutic area | Clinical practice guideline (ID number) | Total number of writers | Number with disclosed ties | Number with no disclosed ties | COI statement available | Developed and funded by government |

| Arthritis | 1 | 15 | 0 | 15 | Yes | No |

| 2 | 26 | 2 | 24 | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | No | Yes | |

| Asthma | 4 | 14 | 0 | 14 | No | Yes |

| 5 | 7 | 0 | 7 | No | No | |

| 6 | 6 | 0 | 6 | No | No | |

| 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | Yes | No | |

| Cancer | 8 | 27 | 4 | 23 | Yes | No |

| 9 | 6 | 1 | 5 | Yes | No | |

| 10 | 14 | 0 | 14 | Yes | Yes | |

| 11 | 31 | 0 | 31 | No | Yes | |

| Cardiovascular | 12 | 11 | 4 | 7 | Yes | No |

| 13 | 4 | 0 | 4 | No | No | |

| 14 | 8 | 1 | 7 | Yes | No | |

| 15 | 34 | 0 | 34 | Yes | No | |

| Diabetes | 16 | 4 | 0 | 4 | No | No |

| 17 | 14 | 0 | 14 | No | No | |

| 18 | 5 | 5 | 0 | Yes | No | |

| 19 | 13 | 0 | 13 | Yes | No | |

| Injury | 20 | 18 | 0 | 18 | No | Yes |

| 21 | 2 | 0 | 2 | No | Yes | |

| 22 | 35 | 4 | 31 | Yes | No | |

| 23 | 9 | 0 | 9 | Yes | Yes | |

| Kidney | 24 | 7 | 1 | 6 | Yes | No |

| 25 | 9 | 2 | 7 | Yes | No | |

| 26 | 6 | 2 | 4 | Yes | No | |

| 27 | 13 | 0 | 13 | No | No | |

| Mental health | 28 | 10 | 10 | 0 | Yes | Yes |

| 29 | 11 | 11 | 0 | Yes | Yes | |

| 30 | 9 | 0 | 9 | Yes | No | |

| 31 | 8 | 0 | 8 | Yes | No | |

| Neurological | 32 | 2 | 0 | 2 | No | No |

| Obesity | 33 | 12 | 7 | 5 | Yes | Yes |

| Total | 402 | 58 | 344 |

COI, conflict of interest.

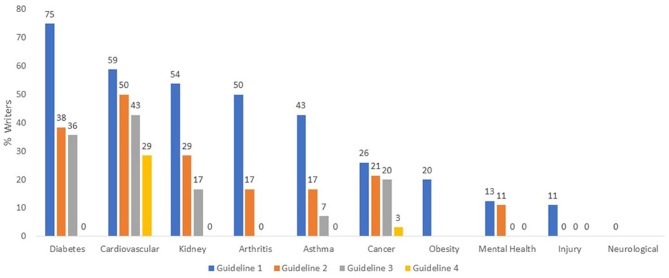

Of 33 guidelines, 23 included at least one writer with a potentially relevant undisclosed tie (70%; 95% CI 51% to 84%) (figure 2). Of those 23 guidelines, 14 guidelines had 20% or more writers who disclosed no ties, but had potentially relevant undisclosed ties. Figure 2 also reveals the proportion of undisclosed ties of guideline writers who disclosed no ties, per guideline, grouped by disease category.

Figure 2.

Proportion of Australian clinical practice guideline writers with undisclosed ties, 2012–2014.

Guideline characteristics and undisclosed ties

Guidelines which included any statement about conflicts of interest were not significantly different from those without statements: 59 of 223 writers (27%) had potentially relevant undisclosed ties, compared with 24 of 121 writers (20%) (risk ratio 1.33; 95% CI 0.88 to 2.03; p=0.170) (table 2). Guidelines both developed and funded by governments, as opposed to non-government groups (including professional bodies, foundations or pharmaceutical companies), were significantly less likely to have authors with potentially relevant undisclosed ties: 8 of 99 writers (8%) compared with 75 of 245 writers (31%) (risk ratio 0.26; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.53; p<0.001).

Table 2.

Proportion of guidelines writers with undisclosed financial ties by guideline type

| Yes | No | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| COI statement in guideline | 59/223 (26.5%) | 24/121 (19.8%) | 1.33 (0.88 to 2.03) | 0.170 |

| Developed, funded by government/s | 8/99 (8.1%) | 75/245 (30.6%) | 0.26 (0.13 to 0.53) | <0.001 |

P value refers to χ2 test.

COI, conflict of interest.

Discussion

In this broad cross-sectional sample of Australian clinical practice guidelines, 14% of guideline writers had published disclosures of conflicts of interest. Among those who either had no disclosures or disclosed they had no conflicts, 24%—almost one in four—had at least one potentially relevant undisclosed financial tie to a pharmaceutical company active in the therapeutic area. More than two-thirds, or 70%, of the 33 guidelines in this sample had at least one writer with an undisclosed tie. Undisclosed financial ties of guideline writers appeared to be more common in some therapeutic areas such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, compared with other areas such as injury and mental health. Guideline writers working on guidelines developed and funded by government were much less likely to have undisclosed financial ties: 8% compared with 31%.

There are important limitations to this study. First, the results likely underestimate the frequency of undisclosed ties for several reasons: there is a general under-reporting of ties published in medical journals as many important transfers of benefits to professionals, such as hospitality or industry-subsidised education, are not routinely disclosed; Australia did not at the time have a database with information on company payments to individuals; and we did not search for any potentially relevant undisclosed ties of writers who made disclosures of ties in the guideline, whether those ties were to pharmaceutical companies or other groups. Second, our results may tend to a small degree to overestimate the frequency of undisclosed ties, through what some may see as a broad definition of potential relevance; for example, categorising a co-investigator of a study funded by a pharmaceutical company active in the therapeutic area as a potentially relevant tie. Third, the sample of guidelines, while broad and accessible, comes from 2012 to 2014—the most recent years available for this sample from a comprehensive collection—admitting the possibility of change since that time. And fourth, we looked only at financial ties, not other non-financial conflicts of interest. The strengths of the study lie in it being the largest to date in terms of guideline writers and undisclosed ties to industry, as well as covering a broad cross-section of disease categories and guideline developers—both government and non-government—with previous smaller studies limited to specific therapeutic areas,4 5 or guidelines produced only by specialty societies.6

Neuman and colleagues investigated the prevalence of conflicts of interest among panels producing 14 North American guidelines for high cholesterol and diabetes.4 They reported that among writers who formally declared no conflicts, 11% had one or more. Looking at a small sample of 49 writers of head and neck surgery guidelines, Horn and colleagues found 6% had discrepancies between guideline disclosures and information available in the Open Payments transparency database.5 Analysing Danish specialty society guidelines, and cross-checking disclosures against a public register of disclosures, Bindsley and colleagues estimated 52% of 254 guideline writers had not disclosed ties.6 A possible explanation of why our estimate of 24% sits within these finding is that the North American studies used narrower timeframes to search for undisclosed ties, while the Danish study defined a conflict of interest as any affiliation with any drug company.

As others have stated, guideline writer ties to companies with interest in the guideline’s outcome raise critical questions about potential bias in processes that may have great impacts on the use of healthcare interventions,4 12 disease definitions19 and patient care. Findings of potentially relevant undisclosed ties compound the problem further and raise the spectre of hidden bias, increasing the wariness of guideline users. Contemporary community standards now demand total transparency, and our findings of undisclosed ties add weight to calls for reforms like the Sunshine Act and Open Payments system in the USA,20 ‘publicly accessible registries of researcher conflicts of interest’,21 and more immediately, enforcement of current disclosure policies to minimise undisclosed ties. In line with repeated recommendations for greater independence between health professionals and industry,1 2 12 our incidental finding that almost one in five of these guidelines had less than 10% of writers with any ties to industry shows it is possible to assemble guideline panels almost entirely free of financial conflicts of interest.

The related reform processes of enhanced transparency and greater independence underway in many nations creates clear opportunities for research comparing the quality of guidelines developed by writers with and without links to industry, a research question beyond the scope of this study, and where there are currently limited data.22 Similarly, there is a need for more research investigating the impacts of links between industry and the professional organisations which auspice guideline development, with one recent study suggesting such ties are ‘common and infrequently disclosed’.23 Given their potential influence over human health, and health system sustainability, such vital research on the independence and trustworthiness of guidelines will be greatly enhanced by complete transparency around the financial conflicts of interest of those developing them.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Edward Luca, who helped develop the search for guideline writer publications.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: RM, AL, HJ, GD, SG and LB conceived and designed the study. RM and LB supervised the study. RM, AL, EB and LB analysed the data. RM, AL, HJ, GD, SG, EB and LB interpreted the data. RM wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and RM, AL, HJ, GD, SG, EB and LB were involved in revisions of the manuscript. RM and LB are guarantors. All authors contributed to the planning, conduct and reporting of this study. All authors had full access to all data and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Funding: RM is supported by a research fellowship funded by NHMRC, GNT1124207. EB is supported by grants from NHMRC to the Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice, Bond University.

Competing interests: HJ was an employee of NHMRC. SG and GD are employees of NHMRC. LB is an employee of The University of Sydney and had no funding specifically for this work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We will share data where possible, within confines of guidance from Bond University Ethics Committee that the paper does not identify or describe any individuals.

References

- 1. Lo B, Field MJ. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Editors: Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, Report Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, et al. . Conflict of interest in clinical practice guideline development: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e25153 10.1371/journal.pone.0025153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, et al. . Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ 2011;343:d5621 10.1136/bmj.d5621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horn J, Checketts JX, Jawhar O, et al. . Evaluation of industry relationships among authors of otolaryngology clinical practice guidelines. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;144:194 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bindslev JB, Schroll J, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . Underreporting of conflicts of interest in clinical practice guidelines: cross sectional study. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:19 10.1186/1472-6939-14-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, et al. . Industry sponsorship and research outcome cochrane database of systematic reviews. First published 16 February 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahn R, Woodbridge A, Abraham A, et al. . Financial ties of principal investigators and randomized controlled trial outcomes: cross sectional study. BMJ 2017;356:i6770 10.1136/bmj.i6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guyatt G, Akl EA, Hirsh J, et al. . The vexing problem of guidelines and conflict of interest: a potential solution. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:738–41. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Handbook for Guideline Development. WHO 2nd ed Geneva, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health and Medical Research Council. Annual Report on Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health and Medical Research Council. Identifying and managing conflicts of interest. NHMRC Public Consultation Version 2017. https://consultations.nhmrc.gov.au/files/consultations/drafts/identifyingandmanagingconflictsofinterest.pdf (accessed 12 Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13. STROBE Statement—Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies. https://www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_cross-sectional.pdf (accessed 12 Apr 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. WHO Conflict of Interest Guidelines: declaration of interests for WHO experts, 2010. http://keionline.org/node/1062 (accessed 12 Apr 2018). 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boyd EA, Bero LA. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 4. Managing conflicts of interests. Health Res Policy Syst 2006;4:16 10.1186/1478-4505-4-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Care Services. Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forsyth SR, Odierna DH, Krauth D, et al. . Conflicts of interest and critiques of the use of systematic reviews in policymaking: an analysis of opinion articles. Syst Rev 2014;3:122 10.1186/2046-4053-3-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moynihan RN, Cooke GP, Doust JA, et al. . Expanding disease definitions in guidelines and expert panel ties to industry: a cross-sectional study of common conditions in the United States. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001500 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Open Payments database. https://www.cms.gov/openpayments/ (accessed 12 Apr 2018).

- 21. Dunn AG, Coiera E, Mandl KD, et al. . Conflict of interest disclosure in biomedical research: a review of current practices, biases, and the role of public registries in improving transparency. Res Integr Peer Rev 2019;1:1 Epub 2016 May 3 10.1186/s41073-016-0006-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cosgrove L, Bursztajn HJ, Erlich DR, et al. . Conflicts of interest and the quality of recommendations in clinical guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:674–81. 10.1111/jep.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Campsall P, Colizza K, Straus S, et al. . Financial relationships between organizations that produce clinical practice guidelines and the biomedical industry: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002029 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025864supp001.pdf (55.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025864supp002.pdf (47.1KB, pdf)