Abstract

Objective

To study the association of genes involved in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) pathway with body mass index (BMI) and obesity risk.

Design

This work studies three cross-sectional populations from Spain, representing three provinces: HORTEGA (Valladolid, Northwest/Centre), SEGOVIA (Segovia, Northwest/centre) and PIZARRA (Malaga, South).

Setting

Forty-eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from MRC genes were selected and genotyped by SNPlex method. Association studies with BMI and obesity risk were performed for each population. These associations were then verified by analysis of the studied population as a whole (3731 samples).

Participants

A total of 3731 Caucasian individuals: 1502 samples from HORTEGA, 988 from PIZARRA and 1241 from SEGOVIA.

Results

rs4600063 (SDHC), rs11205591 (NDUFS5) and rs10891319 (SDHD) SNPs were associated with BMI and obesity risk (p values for BMI were 0.04, 0.0011 and 0.0004, respectively, and for obesity risk, 0.0072, 0.039 and 0.0038). However, associations between rs4600063 and BMI and between these three SNPs and obesity risk are not significant if Bonferroni correction is considered. In addition, rs11205591 and rs10891319 polymorphisms showed an additive interaction with BMI and obesity risk.

Conclusions

Several polymorphisms from genes coding MRC proteins may be involved in BMI variability and could be related to the risk to become obese in the Spanish general population.

Keywords: obesity, snp, mitochondrial respiratory chain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This research was conducted in three open populations from different provinces of Spain.

Mitochondrial respiratory chain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) analysis by SNPlex genotyping method overcomes some of the limitations of genome- wide association studies.

One of the limitations of this study is the reduced size of the populations used

Despite the limited number of individuals in this study, the statistical power is sufficient for the number of analysed SNPs.

Results from this study are promising and should be validated by larger sample sizes.

Introduction

Obesity is a metabolic disorder consisting of excess body fat accumulation. Obesity prevalence has been increasing during the last decades in Western societies, becoming one of the most important public health problems due to its causal relationship with several chronic diseases such as insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1

Susceptibility to obesity is determined by environmental and genetic factors. Although rising obesity prevalence is triggered by lifestyle changes, the risk of developing obesity has an important genetic component, which has been examined in numerous studies.2–4 Rare mutations in genes encoding for appetite-regulating proteins, such as leptin (LEP) and its receptor (LEPR), melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), have been shown to cause severe early-onset obesity.5 6 Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified common polymorphisms located in, or near to, 97 loci, mostly expressed in the central nervous system.6–10 However, it is also suggested that, due to limitations of GWAS, there are around 250 common variants with a similar effect to those previously described that remain to be identified.8

The study of target genes or genes involved in a particular physiological pathway is a potential approach to identify genetic variants with roles in complex traits. The mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC) is a biological system involved in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism through oxidative phosphorylation. MRC produces the proton gradient needed for ATP synthesis and is composed of four large complexes (I to IV) that transport electrons from donors (NADH at complex I, FADH2 at complex II) to acceptors. Finally, electrons in complex IV are conducted to the last acceptor, the molecular oxygen.11 Mitochondrial oxidative capacity dysfunction in liver, muscle or adipose tissue could contribute to the intracellular accumulation of fatty acids observed in obesity.12 13 Insulin resistance has been associated with lower mitochondria activity at rest.14 This may be the result of inherited defects in genes coding MRC proteins.

Mutations of MRC genes resulting in loss of function have been reported to produce major disability-causing diseases.15–18 In addition, studies on their impact on energy efficiency and expenditure have shown an association with the risk of developing obesity.12 19–21 Studies have also shown that obesity affects the function of mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction.22 Mitochondrial dynamics play a role in metabolism and obesity: MFN2, a gene coding for a GTPase in the outer mitochondrial membrane is involved in mitochondrial fusion, regulating the operation of the mitochondrial network in skeletal muscle. When MFN2 is repressed, glucose oxidation and mitochondrial membrane potential are impaired.23 It has been shown that expression of MNF2 is repressed in obese patients compared with lean.23 Furthermore, polymorphisms in MRC genes, or others related to its regulation, have been related to obesity in different populations.23–25

The aim of this study was to find associations between MRC nuclear genes, body mass index (BMI) and obesity in three different Spanish studies in the general population.

Materials and methods

Sample populations

We independently analysed three general Spanish populations originally recruited for the study of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease development: HORTEGA (1502 subjects collected from 2004 to 2005), PIZARRA (988 individuals, collected from 2009 and 2010) and SEGOVIA (1239 subjects, collected between 2000 and 2003).26–28 The HORTEGA sample involves subjects from the Valladolid area (Northwestern Spain). The PIZARRA sample comprises subjects from Pizarra, a town in the Malaga province (Andalusia, Southern Spain). The SEGOVIA sample studied subjects from the Segovia Province (Centre of Spain). These three populations were recruited to identify cardiovascular risk factors in the general population as an overall goal. Individuals were randomly selected and invited to participate. Exclusion criteria were any concomitant disease or condition that prevented them from answering a survey, or donating a sample or that would influence the collection of reliable information. The study was approved. All patients provided informed written consent to take part in the investigations. The research was carried out according to the Ethical Principles of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Demographic data and anthropometric parameters were collected following standard procedures. Presence of obesity, hypertension (HTN) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was recorded. BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared. Obesity, HTN and T2DM were defined using the WHO criteria (http://www.who.int). Briefly, obesity was diagnosed with a BMI >30 kg/m2, overweight as BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2 and normal weight as BMI <24.9 kg/m2. HTN was defined by systolic and diastolic blood pressure above 140 or 90 mm Hg, respectively. T2DM was defined by fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or 2-hour plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL. Previous diagnosis of T2DM or HTN and detection of the disease at the moment of sample collection were recorded. Missing data for parameters regarding this work (expressed as HORTEGA missing data/PIZARRA missing data/SEGOVIA missing data) were 58/58/6 for BMI and 1/85/63 for glucose.

We have calculated the statistical power for our three samples independently (minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.10, genotype relative risk (1.5)), number of obese and non-obese and prevalence of obesity in each of the populations. Furthermore, the statistical power was over 85% for these conditions in all populations and it increases for increased allele frequency (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/cats/gas_power_calculator/index.html).

Genotyping methods

Gene and single nucleotide polymorphisms selection

Forty-eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of chromosomal genes coding for MRC proteins were selected for genotyping. Selection was performed based on the following considerations: functionality (previously described or possible effect), MAF ≥1%, representation of genetic variability of the whole gene (HapMap polymorphisms) and spacing along the gene. Most important variants described in the literature were included. Details of genes and SNPs included are shown as online supplemental material (table 1S).

bmjopen-2018-027004supp001.pdf (95.6KB, pdf)

Genotyping procedure

Venous blood samples were collected in tubes containing EDTA. DNA was isolated by standard commercial procedures (Chemagic Magnetic Separator from Chemagen, Baesweiler, Germany). DNA was quantified and diluted to a final concentration of 100 ng/µL.

SNPlex (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) was used for genotyping, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. SNPlex is a genotyping system based on oligonucleotide ligation assay/PCR technology that analyses 48 SNPs. Those SNPs were chosen as explained above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.19 and SNPStats software.29

Chi-squared test and variance analysis were used to compare quantitative and categorical variables between groups in order to assess general characteristics of the studied populations. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

When analysing for associations between SNPs and obesity traits in the three populations, 11 out of the 48 SNPs were excluded from the study because they did not fulfil the Hardy-Weimberg equilibrium, had low frequency or were not detectable by the genotyping procedure. Hardy-Weimberg test indicated no loss of heterozygosity in the analysed populations for these SNPs. The Bonferroni correction cut-off to assess significant associations was calculated for the 37 remaining SNPs. Those polymorphisms associated in at least one of the three populations and showing the same tendency in the remaining ones, or results with p values near the nominal cut-off point in the three studies (p<0.05), were also analysed in the 3729 total combined subjects from the three populations. For these analyses, multivariate logistic regression under codominant model was performed and, if applicable, dominant, recessive or additive models were used. For categorical variables, adjusted OR were assessed with 95% CI. The association between polymorphisms and BMI values was examined using analysis of covariance. All p values were two-sided. All results were obtained after adjustment for age and gender, and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not actively involved in this research. They were informed regarding the research goals, protocol development and parameters to be measured before starting the study. If appropriate, they were informed regarding results.

Results

Characteristics of the studied populations

General characteristics of the studied populations are summarised in table 1. Age, gender and BMI varied between the three populations. There were differences in obesity and T2DM percentage: obesity prevalence was 17%, 26% and 33% for Hortega, Segovia and Pizarra studies, respectively, while T2DM prevalence was 7.6%, 10.2% and 19.6%. Increased means of age correspond to the age structure of our population. BMI means correspond to overweight values, what is in agreement with the fact that obesity is increasing in Western societies (WHO).

Table 1.

General features of Hortega, Pizarra and Segovia patients considered individually and as a whole population

| Hortega | Pizarra | Segovia | Whole population | |

| N | 1502 | 988 | 1241 | 3731 |

| Age (years) | 54.4+19.3* | 46.1+13.9*** | 51.9+10.8** | 51.4+15.9 |

| Height (m) | 163.7+10.0* | 161+8.8 | 161.4+9.0** | 162.2+9.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.8+12.9* | 74.1+4.3*** | 72.1+12.4** | 72.1+13.2 |

| BMI kg/m2) | 26.4+4.2* | 28.6+5.3*** | 27.7+4.3** | 27.4+4.6 |

| Gender M(%)/F(%) | 754 (50.2)/748 (49.8)* | 365 (36.9)/(616 (62.3)*** | 562 (45.3)/(679 (54.7)** | 2043 (54.8)/(1681 (45.1) |

| Obesity (N(%)) | 262 (17.4)* | 331 (33.5)*** | 319 (25.7)** | 912 (24.4) |

Values expressed as mean±SD except for gender and obesity. P value <0.05 was considered significant. *For p<0.05 when comparing Hortega with Pizarra; **p<0.05 when comparing Hortega and Segovia; *** for p<0.05 when comparing Pizarra and Segovia.

BMI, body mass index; F, female; M, male.

Association between MRC genes SNPs and obesity

We performed the analysis looking for associations between SNPs, BMI and obesity risk in the three independent populations. Table 2 shows results for SNPS with differences in at least one of the three populations and a similar trend in the remaining ones, or that had p values near the nominal cut-off point (p≤0.05) in the three studies: rs1136224 (NDUFS2 gene), rs11205591 (NDUFS5), rs4600063 (SDHC), rs3770989 (NDUFS1) and rs10891319 (SDHD). These five SNPs were selected for further analysis in the whole population.

Table 2.

BMI and obesity risk of associated SNPs for Hortega, Pizarra and Segovia populations

| Genotype | HORTEGA | PIZARRA | SEGOVIA | |||||||

| N | BMI (kg/m2) | Obesity OR (95% CI) | N | BMI (kg/m2) | Obesity OR (95% CI) | N | BMI (kg/m2) | Obesity OR (95% CI) | ||

| SDHC | AA | 1250 | 26.46±0.12 | 1 | 772 | 28.70±0.19 | 1 | 943 | 27.71±0.10 | 1 |

| rs4600063 | AG-GG | 183 | 26.16±0.30 | 0.82 (0.55 to 1.22) | 96 | 27.86±0.04 | 0.47 (0.28 to 0.78) | 132 | 27.21±0.30 | 0.88 (0.57 to 1.36) |

| HWE: 1 | P value | 0.9 | 0.33 | 0.071 | 0.0025 | 0.22 | 0.57 | |||

| NDUFS1 | TT | 1308 | 26.41±0.12 | 1 | 799 | 28.49±0.10 | 1 | 1028 | 27.56±0.10 | 1 |

| rs3770989 | CT-CC | 114 | 26.62±0.44 | 1.13 (0.72 to 1.77) | 77 | 29.85±0.60 | 1.5 (0.91 to 2.48) | 65 | 27.92±0.60 | 1.28 (0.73 to 2.23) |

| HWE: 1 | P value | 0.34 | 0.6 | 0.016 | 0.12 | 0.48 | 0.39 | |||

| NDUFS2 | AA | 1045 | 26.37±0.13 | 1 | 640 | 28.61±0.21 | 1 | 830 | 27.55±0.15 | 1 |

| rs1136224 | AG-GG | 369 | 26.59±0.23 | 1.43 (1.09 to 1.89) | 223 | 28.59±0.34 | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.54) | 241 | 27.77±0.26 | 1.07 (0.76 to 1.48) |

| HWE: 0.36 | P value | 0.25 | 0.011 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.71 | |||

| NDUFS5 | CC-CG | 1309 | 26.47±0.12 | 1 | 832 | 28.63±0.10 | 1 | 947 | 27.6±0.14 | 1 |

| rs11205591 | GG | 115 | 25.78±0.31 | 0.67 (0.41 to 1.10) | 38 | 27.66±0.70 | 0.86 (0.41 to 1.81) | 89 | 27.21±0.40 | 0.89 (0.53 to 1.5) |

| HWE: 0.76 | P value | 0.049 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.66 | |||

| SDHD | AA | 691 | 26.16±0.16 | 1 | 401 | 28.18±0.26 | 1 | 571 | 27.37±0.17 | 1 |

| rs10891319 | AG-GG | 726 | 26.64±0.16 | 1.16 (0.90 to 1.49) | 478 | 29.00±0.24 | 1.22 (0.91 to 1.64) | 492 | 27.83±0.19 | 1.27 (0.96 to 1.68) |

| HWE: 0.22 | P value | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.084 | 0.18 | 0.077 | 0.095 | |||

BMI: mean±SD.

Bold: significant.

BMI, body mass index; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; N, number of individuals; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Analysing these five SNPS in the total population, four polymorphisms were associated with BMI: rs4600063, rs10891319, rs3770989, rs11205591, located in the SDHC, SDHD, NDUFS1 and NDUFS5, genes, respectively. Results for these four SNPs are shown in table 3: rs4600063 and rs3770989 showed low association with BMI, which lost significance after Bonferroni correction (p<0.0013). Rs10891319 and rs11205591 showed significant association with BMI after Bonferroni correction, with a p value of 0.0004 for the first one and 0.0011 for the second one. On the other hand, rs4600063 (genotypes AG and GG) and rs11205591 (GG genotype) reduced obesity risk, while rs10891319 (AG and GG genotypes) and rs1136224 (AG and GG genotypes) increased the risk (p<0.05), but they did not reach the Bonferroni cut-off point.

Table 3.

SNP genotyping: distribution of BMI levels and the associated obesity risk for all genotypes in whole population

| Gene/SNP | Genotype | N | BMI (kg/m2) | Non-obesity (N(%)) | Obesity (N(%)) | OR (95% CI) |

| SDHC | AA | 2965 | 27.44±0.08 | 2109 (86.9) | 851 (90.4) | 1 |

| rs4600063 | AG-GG | 411 | 26.89±0.21 | 318 (13.1) | 90 (9.6) | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92) |

| P value | 0.04 | 0.0072 | ||||

| SDHD | AA | 1663 | 27.06±0.11 | 1243 (51.3) | 422 (45.4) | 1 |

| rs10891319 | AG-GG | 1696 | 27.60±0.11 | 1178 (48.7) | 508 (54.6) | 1.25 (1.08 to 1.46) |

| P value | 0.0004 | 0.0038 | ||||

| NDUFS1 | TT | 3135 | 27.32±0.08 | 2273 (92.9) | 857 (91.2) | 1 |

| rs3770989 | CT-CC | 256 | 27.92±0.32 | 173 (7.1) | 83 (8.8) | 1.30 (0.99 to 1.72) |

| P value | 0.026 | 0.066 | ||||

| NDUFS2 | AA | 2515 | 27.33±0.09 | 1833 (76.1) | 680(73) | 1 |

| rs1136224 | AG-GG | 833 | 27.46±0.16 | 575 (23.9) | 251(27) | 1.20 (1.01 to 1.43) |

| P value | 0.31 | 0.041 | ||||

| NDUFS5 | CC-CG | 3088 | 27.40±0.08 | 2219 (92.3) | 863(94) | 1 |

| rs11205591* | GG | 242 | 26.60±0.24 | 184 (7.7) | 55(6) | 0.72 (0.52 to 0.99) |

| P value | 0.0011 | 0.039 |

Bold: significant, p<0.05.

*tag-SNP.

BMI values are expressed as mean±SD. Results after adjustment for the following variables included in the model: age and gender.

N, number of individuals; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

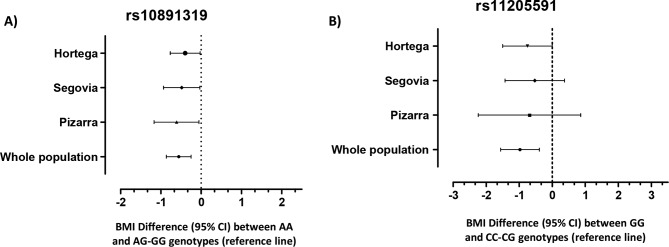

Figure 1 shows BMI differences for rs10891319 and rs11205591 polymorphisms in each independent population and as a whole. A similar trend can be observed in both figure 1A,B, although only the rs11205591 SNP reaches significance in the HORTEGA study (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Body mass index (BMI) differences found for the associated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) genotypes for each population analysed in this study. Values are expressed as BMI difference means, showing 95% CI. (A) rs10891319 BMI differences between AG-GG and AA genotypes, taking the first one (BMI difference=0 for carriers of AG-GG genotype) as reference. (B) rs11205591 BMI differences for CC-CG and GG genotypes, with the first one as a reference (CC-CG genotype BMI difference=0).

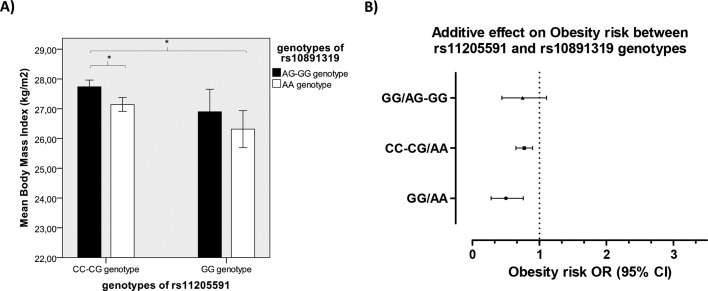

We studied additive effects for all these SNPs and an additive effect for rs11205591 and rs10891319 SNPs was found in the whole sample: patients carrying GG/AA combination presented significant lower BMI (figure 2A) and lower obesity risk (figure 2B) than patients carrying CC-CG/AG GG genotypes (data are expressed as rs11205591 genotype/rs10891319 genotype).

Figure 2.

Additive effect of rs10891319 and rs11205591 genotype combination in body mas index (BMI) and obesity risk. (A) BMI means. * indicates a p value <0.005. (B) Obesity risk ORs. Rs11205591 CC-CG/rs10891319 AA genotypes were taken as a reference (OR=1). The obtained p value was <0.003. Error bars show SE. Data are expressed as rs11205591/rs10891319 genotypes.

On the other hand, some of the SNPs were within the gene. We calculated possible haplotypes, with negative results.

Discussion

The goal of this population-based study was to analyse MRC SNPs and their association with BMI and obesity risk in three Spanish populations. SNPs with the most relevant associations were tested in the pooled sample.

We found a significant protective association with the risk of obesity for rs10891319 AA, and for patients with the rs11205591 GG genotype, who also showed reduced BMI. Despite differences in age, sex, BMI and obesity prevalence between the three samples, a similar trend was found considering them individually, while rs10891319 showed the strongest in the whole sample. Furthermore, an additive interaction was observed between these two SNPs, with a maximal BMI difference of 1.4 kg/m2 found between genotypes (CC-GG/AA GG vs GG/AA carriers, expressed as rs11205591/rs10891319 genotype carriers). In agreement with these findings, significant differences in obesity risk were also found.

Another SNP associated with BMI in one of the three populations and in the whole group, rs3770989, is located in the 3’UTR region of the NDUFS1 gene, which codes for NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 1. In silico analysis in TargetScanHuman (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_50/) showed that this SNP is located between two regions of miRNA binding sites, although it does not seem to affect either of them.30 31 On the other hand, the rs11205591 and rs10891319 SNPs are located in 3’ regions of NDUFS5 and SDHD genes, respectively. Although these SNPs have an unknown functional effect, they could be in linkage disequilibrium with other truly functional polymorphisms. New studies are needed to address this question.

The first gene consistently identified as an obesity gene using GWAS was FTO. Several SNPs located on its first intron were associated with BMI in European, East Asian and African populations.32 33 Following this gene, 75 additional obesity loci have been identified using this methodology and, although FTO is the gene accounting for most of the interindividual variability on BMI, it only explains a 0.34%.8 33 There are data supporting that alterations in genes related to mitochondrial function can be involved in obesity,12 15 20 21 34 but few studies have analysed the effect of its variations on BMI or obesity.19 24 From all genes identified in the GWAS meta-analysis performed by Speliotes and colleagues,8 only the NDUFS3 (NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 3) gene was identified to be within 300 kb from the BMI-associated SNPs. As these authors indicated, in spite of the large population analysed in their study, many genetic variants related to BMI and obesity remain to be identified. The limitations of this meta-analysis come from the different microarrays used, with low coverage in many genomic regions. Therefore, the NDUFS5 gene (where rs11205591 is located) has been analysed by only one polymorphism in each of the two most used microarrays by Speliotes and in most of the GWAS performed to date8 (http://www.Illumina.com; http://www.affymetrix.com; http://www.ensembl.org). In addition, representation of Mediterranean populations in Speliotes and Locke’s studies is very small, and, to our knowledge, Spanish populations are not included.8 9 Therefore, many important genetic regions, related to BMI and obesity regulation in these populations, may be missing from their work.

The present study supports the hypothesis that genetic variations in MRC genes may be related to obesity susceptibility in the Spanish population. Therefore, these genes could be new therapeutic targets. Genetics of obesity are complex and not yet well identified, and our data may contribute to a better understanding. One limitation of this study is the reduced size of the analysed populations. However, the statistical power is sufficient for the number of analysed SNPs. On the other hand, we have not studied all the possible SNPs present in these MRC genes. Further functional studies and association analyses in larger samples and other populations should be carried out to confirm our results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Manuel Serrano-Rios (Diabetes Research Laboratory, Biomedical Research Foundation from University Clinic Hospital San Carlos (Madrid, Spain) and CIBER of Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Diseases (CIBERDEM), Madrid, Spain) for his kind contribution in the development of this work.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: GDM: obtained genetic data, analysed and interpreted results and wrote the manuscript. VGA obtained genetic data, contributed to analysis and interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. JTR, LSBF, MCS, ALS and AC obtained population data, made critical revisions of the manuscript and contributed to the discussion. JCME, GRM, RC and MTML contributed to population studies and discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. FJC and ABGG designed the study, wrote the manuscript, contributed to discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by CIBER of Physiopathology, Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROB) and CIBER of Diabetes and Metabolic Associated Diseases (CIBERDEM), initiatives of Carlos III Health Institute, Spanish Health Ministry; Project INGENFRED CIBER-02-08-2009 (CIBERDEM); research grants PI070497, PI081592, PI14/00874 and PIE14/00031 from the ‘Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias’; ACOMP/2009/201, GRUPOS03/101, 2005/027 and PROMETEO/2009/029 from the Valencian Government and grant SAF2005-02883 from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science; GRS 279/A/08 of Regional Health Management of Castilla y León, Junta de Castilla y León.

Disclaimer: Neither funder played a role in the study design, data analysis or interpretation of the data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Research and EthicsCommittee from the Valencia University Clinical Hospital and INCLIVA (referencenumber 2010/013).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Marques A, Peralta M, Naia A, et al. . Prevalence of adult overweight and obesity in 20 European countries, 2014. Eur J Public Health 2018;28:295–300. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stunkard AJ, Foch TT, Hrubec Z. A twin study of human obesity. JAMA 1986;256:51–4. 10.1001/jama.1986.03380010055024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chung WK, Leibel RL. Considerations regarding the genetics of obesity. Obesity 2008;16:S33–9. 10.1038/oby.2008.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheikh AB, Nasrullah A, Haq S, et al. . The interplay of genetics and environmental factors in the development of obesity. Cureus 2017;9:e1435 10.7759/cureus.1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andreasen CH, Andersen G. Gene-environment interactions and obesity--further aspects of genomewide association studies. Nutrition 2009;25:998–1003. 10.1016/j.nut.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vimaleswaran KS, Loos RJ. Progress in the genetics of common obesity and type 2 diabetes. Expert Rev Mol Med 2010;12:e7 10.1017/S1462399410001389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fawcett KA, Barroso I. The genetics of obesity: FTO leads the way. Trends Genet 2010;26:266–74. 10.1016/j.tig.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, et al. . Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet 2010;42:937–48. 10.1038/ng.686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. . Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015;518:197–206. 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodarzi MO. Genetics of obesity: what genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:223–36. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30200-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johannsen DL, Ravussin E. The role of mitochondria in health and disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2009;9:780–6. 10.1016/j.coph.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abdul-Ghani MA, DeFronzo RA. Mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep 2008;8:173–8. 10.1007/s11892-008-0030-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Z, Yuan D, Duan Y, et al. . Key factors involved in obesity development. Eat Weight Disord 2018;23 10.1007/s40519-017-0428-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szendroedi J, Phielix E, Roden M. The role of mitochondria in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;8:92–103. 10.1038/nrendo.2011.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fosslien E. Review: Mitochondrial medicine--cardiomyopathy caused by defective oxidative phosphorylation. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2003;33:371–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rötig A, Munnich A. Genetic features of mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:2995–3007. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000095481.24091.C9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu X, Peng X, Guan MX, et al. . Pathogenic mutations of nuclear genes associated with mitochondrial disorders. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 2009;41:179–87. 10.1093/abbs/gmn021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rodenburg RJ. Mitochondrial complex I-linked disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1857:938–45. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pospisilik JA, Knauf C, Joza N, et al. . Targeted deletion of AIF decreases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and protects from obesity and diabetes. Cell 2007;131:476–91. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harper ME, Green K, Brand MD. The efficiency of cellular energy transduction and its implications for obesity. Annu Rev Nutr 2008;28:13–33. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bournat JC, Brown CW. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2010;17:446–52. 10.1097/MED.0b013e32833c3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Mello AH, Costa AB, Engel JDG, et al. . Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Life Sci 2018;192:26–32. 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dunham-Snary KJ, Ballinger SW. Mitochondrial genetics and obesity: evolutionary adaptation and contemporary disease susceptibility. Free Radic Biol Med 2013;65:1229–37. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kunej T, Wang Z, Michal JJ, et al. . Functional UQCRC1 polymorphisms affect promoter activity and body lipid accumulation. Obesity 2007;15:2896–901. 10.1038/oby.2007.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jackman MR, Ravussin E, Rowe MJ, et al. . Effect of a polymorphism in the ND1 mitochondrial gene on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Obesity 2008;16:363–8. 10.1038/oby.2007.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mansego ML, Redon J, Marin R, et al. . Renin polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with blood pressure levels and hypertension risk in postmenopausal women. J Hypertens 2008;26:230–7. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f29865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soriguer-Escofet F, Esteva I, Rojo-Martinez G, et al. . Diabets Group of the Andalusian Society of Endocrinology and Nutrtion. Prevalence of latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA) in Southern Spain. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2002;56:213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martínez-Larrad MT, Fernández-Pérez C, González-Sánchez JL, et al. . [Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome (ATP-III criteria). Population-based study of rural and urban areas in the Spanish province of Segovia]. Med Clin 2005;125:481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Solé X, Guinó E, Valls J, et al. . SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics 2006;22:1928–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, et al. . MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 2007;27:91–105. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, et al. . Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 2009;19:92–105. 10.1101/gr.082701.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, et al. . A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science 2007;316:889–94. 10.1126/science.1141634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loos RJ, Yeo GS. The bigger picture of FTO: the first GWAS-identified obesity gene. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014;10:51–61. 10.1038/nrendo.2013.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Okura T, Koda M, Ando F, et al. . Association of the mitochondrial DNA 15497G/A polymorphism with obesity in a middle-aged and elderly Japanese population. Hum Genet 2003;113:432–6. 10.1007/s00439-003-0983-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027004supp001.pdf (95.6KB, pdf)