Abstract

Objective

There is increasing awareness of the burden of medical care experienced by those with multimorbidity. There is also increasing interest and activity in engaging patients with chronic disease in technology-based health-related activities (‘eHealth’) in family practice. Little is known about patients’ access to, and interest in eHealth, in particular those with a higher burden of care associated with multimorbidity. We examined access and attitudes towards eHealth among patients attending family medicine clinics with a focus on older adults and those with polypharmacy as a marker for multimorbidity.

Design

Cross-sectional survey of consecutive adult patients attending consultations with family physicians in the McMaster University Sentinel and Information Collaboration practice-based research network. We used univariate and multivariate analyses for quantitative data, and thematic analysis for free text responses.

Setting

Primary care clinics.

Participants

693 patients participated (response rate 70%). Inclusion criteria: Attending primary care clinic. Exclusions: Too ill to complete survey, cannot speak English.

Results

The majority of participants reported access to the internet at home, although this decreased with age. Participants 70 years and older were less comfortable using the internet compared with participants under 70. Univariate analyses showed age, multimorbidity, home internet access, comfort using the internet, privacy concerns and self-rated health all predicted significantly less interest in eHealth. In the multivariate analysis, home internet access and multimorbidity were significant predictors of disinterest in eHealth. Privacy and loss of relational connection were themes in the qualitative analysis.

Conclusion

There is a significant negative association between multimorbidity and interest in eHealth. This is independent of age, computer use and comfort with using the internet. These findings have important implications, particularly the potential to further increase health inequity.

Keywords: ehealth, multimorbidity, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this study is its routine primary care setting. The study population reflects the population attending primary care appointments, and therefore most likely to be exposed to eHealth initiatives.

The high response rate provides quantitative estimation of patient perspectives in an area where data are lacking, despite great activity in health service delivery initiatives focused on eHealth.

Focus on older adults, and those with polypharmacy as a marker for complex medical care in multimorbidity.

Selection bias may have occurred: the research assistants noted that almost half of non-respondents indicated they did not have internet access and, despite encouragement, indicated that for that reason did not want to participate. We may therefore overestimate internet access.

A larger sample size may reveal more nuanced predictions within the model; however, no other variables approached a level of significance suggesting influences as important as polypharmacy. The use of a short questionnaire suitable for use in a routine clinical setting maximised response rate to accurately assess prevalence. This may not allow for, but complements, in-depth insight into patient perspectives of eHealth which requires a different methodological approach.

Introduction

There is great interest from primary care clinicians, service providers and policymakers in the potential to use technology to improve care at the population and individual clinical level, especially in those with long-term health problems. The term eHealth came into use in around 2000 and is defined as: ‘the cost-effective and secure use of information and communications technologies in support of health and health-related fields, including health-care services, health surveillance, health literature and health education, knowledge and research.’1

Patients are being engaged more often in technology-based health activities (‘eHealth’) in day-to-day family medicine, such as booking appointments, gathering health information, communicating with their health team and using an electronic personal health record to monitor health online, though there is little evidence to date for a significant impact on clinical outcomes, particularly patient-relevant outcomes.2

However, there are concerns that eHealth may increase health inequity if there is differential interest in and access to it, and chronic disease and multimorbidity are more prevalent in deprived populations.3 In parallel, there is increasing awareness of the burden of medical care experienced by those with multimorbidity, to the extent that it may overwhelm patients’ ability to cope.4 The ‘inverse care law’ describes the maldistribution of provision of, or access to, medical resources where the availability of good medical or social care tends to vary inversely with the health need of the population served. Increasing the health of those with the best health status increases the inequity gap.5

What is known about patients’ perspectives on eHealth?

In 2011, Perera and colleagues showed most patients support the computerised sharing of their health records among their healthcare professionals providing clinical care.6 Fewer agreed that the patient’s deidentified information should be shared beyond this group (<70%).6 Privacy concerns have been expressed about electronic versus paper records; however, most patients (58%) believe the benefits outweigh the risks.

Activities and technologies related to eHealth require access to and use of the internet (eg, to access a personal health record), and sometimes a home wireless internet (Wi-Fi) network is also required (eg, health monitoring devices that depend on Wi-Fi in the home). Computer and internet use have become more prevalent among seniors over the past 15 years.7 There is research on how and why seniors use computers and the internet, but little information on access to Wi-Fi at home.8

Some qualitative literature indicates the potential interest in and issues for eHealth among patients with multimorbidity. One qualitative study among 53 patients with multimorbidity who were already eHealth technology users assessed challenges and gaps in available technology and approaches, such as managing the high volume of information and tasks, and coordinating and synthesising information for multiple conditions as well as meaningful engagement of their multiple providers.9 Similar themes emerged in a qualitative study in Canada among 14 patients with multimorbidity who also reported both interest in the potential of eHealth but concerns related to privacy, accessibility, the loss of necessary visits, increased social isolation and the downloading of responsibility onto patients for care management.10 These latter themes were also echoed in a study using semistructured interviews among 10 patients in Denmark. In this study patient-perceived value of eHealth and interest in using was variable and there were some signals this may be linked to treatment burden. There is even less information available in the literature about the range and extent of patient perceptions and concerns about eHealth activities relating to the structure and content of their clinical care, particularly among seniors and people with multimorbidity.11 This is an important gap as eHealth activities are often aimed at patients with chronic disease, and chronic disease is usually manifest in the context of multimorbidity. The risk of multimorbidity increases in seniors; however, the absolute number of patients with multimorbidity is now greater under age 6512; so these groups overlap, but are not identical. Data on patient perspectives on ability and desire to engage in eHealth are essential in order to understand any potential for increasing health inequity at the population level, while a patient-centred perspective mandates understanding patients’ views prior to implementing any changes in clinical care.

We carried out a cross-sectional survey of patients attending primary care to estimate the occurrence of internet access, home Wi-Fi access, device use and comfort using the internet. We also examined the attitudes of patients towards eHealth activities and the use of online health records. We planned subgroup analyses to assess these domains among older adults and those with the more complex care needs of multimorbidity.

Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional survey.

Participants and setting

Consecutive patients attending primary care appointments with physicians who are part of the McMaster University Sentinel and Information Collaboration (MUSIC) primary care practice-based research network were invited to participate in a survey. This network covers 36 887 enrolled patients, including 28 128 patients over 18, located in Hamilton, Ontario. These practices have good representation from low and middle socioeconomic status (SES) areas and the demographic characteristics are outlined in table 1. Patients were excluded if they were under 18, too ill to complete the survey or did not speak English. Questionnaires were administered in the clinics’ waiting areas from mid-December 2014 to mid-January 2015.

Table 1.

Patient sample characteristics

| Sample n (%) |

MUSIC PBRN* n (%) |

|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 249 (35.9) | 11 659 (43.8) |

| Female | 424 (61.2) | 14 910 (56.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 9 (0.03) |

| No response | 19 (2.7) | |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 77 (11.1) | 6157 (26.1) |

| 30–39 | 75 (10.8) | 5074 (19.0) |

| 40–49 | 97 (14.0) | 4481 (16.8) |

| 50–59 | 159 (22.9) | 4475 (16.8) |

| 60–69 | 135 (19.5) | 3385 (12.7) |

| 70–79 | 92 (13.3) | 1745 (6.5) |

| 80+ | 43 (6.2) | 1261 (4.7) |

| No response | 15 (2.1) | |

| Ethnicity† | ||

| European origins | 572 (82.5) | Not available |

| Latin, Central and South American origins | 13 (1.9) | |

| African origins | 34 (4.9) | |

| Asian origins | 34 (4.9) | |

| No response/other | 55 (7.9) | |

| Income | ||

| Mean (IQR) | $42 887 ($12 191) | Not available |

*McMaster University Sentinel and Information Collaboration (MUSIC) Practice Based Research Network (PBRN) rostered adult population (18+ years).

†Multiple option recording allowed.

Sample size

We estimated from clinic data that around one in six patients attending was age 70 and over, so we aimed to recruit at least 600 patients in order to include at least 100 seniors aged 70 and over in the sample, as we were interested in subgroup analyses for seniors as well as patients with multimorbidity.

Data collection

Patients completed a questionnaire designed to elicit their access to the internet, wireless devices and their general views on eHealth. eHealth was defined for participants as, ‘Activity in booking appointments, gathering health information, communicating with your family health team and personalized monitoring and information around your health online.’ After providing informed consent, patients self-completed the questionnaire except where physical disability or literacy problems prevented this—in which case they could choose to have it administered by the research assistant interviewer.

The questionnaire was developed and piloted for face validity with academic staff, and then in a pilot sample of 10 older adults. Questionnaire items were modified based on feedback from these pilots. A focus was on pragmatic design to create a questionnaire that could be easily completed while waiting for an appointment to maximise response rate. The questionnaire gathered basic demographic information, and the number of long-term medications was a proxy indicator for multiple chronic conditions. All data were collected by self-report as, to maximise response, the questionnaire was administered in a waiting room with no identifying information. Questionnaire items covered the following domains: home internet access, home Wi-Fi access, degree of confidence using the internet and types of devices used. We also asked participants about their level of interest in eHealth and any concerns that they had around eHealth or around privacy with respect to eHealth. The questionnaire items gathered quantitative data using five-point Likert items (from strongly agree to strongly disagree with a neutral midpoint) and precoded categorical responses. Free text responses were also sought on concerns surrounding eHealth.

We assessed two key subgroups in analyses: age 70 and over, and those using five or more long-term medications. We used this measure of use of five or more medications in this study as an estimate of multimorbidity with significant treatment burden. We used number of medications rather than self-reported condition number to define multimorbidity as we wished to define a population for subgroup analysis who experienced more complex care, including polypharmacy. The definition of multimorbidity varies depending on which conditions are defined as diseases (vs risk factors and syndromes) and which are included in the multimorbidity list. Getting patients to list all conditions would have added to the time burden, potentially compromising response rate. Further, our previous work in this same population demonstrated patient self-report was inaccurate for estimating the degree of multimorbidity.13 14 We therefore chose number of medications as a pragmatic approach to defining our subgroup for analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or implementation of this study.

Potential for bias and confounding

Multimorbidity is more common in lower socioeconomic groups.15 It is also likely that lower SES limits an individual’s access to computers and internet/Wi-Fi. Patients who do not access the internet and therefore have less appreciation of what eHealth might mean may not know how they might feel about eHealth and related domains of the survey. The patients served by the MUSIC network represent a wide range of SES, coming from a wide range of neighbourhoods within Hamilton, Ontario and the surrounding area with clinics located in both suburban Hamilton with a higher SES, and in downtown Hamilton with a much lower SES. All patients attending these clinics in the study period had the same chance of being approached for study recruitment.

Analysis and statistical methods

Data were entered from the questionnaires into a Microsoft Access database. A randomly selected sample of 10% was double entered and the error rate was less than 1%. All analyses were carried out in OpenEpi3.03a.com and SPSS V.22.0.16 17 Contingency tables were analysed by χ2 tests plus confidence limits for proportions and risk differences. We were interested in the influence of different variables on patient interest in eHealth. We carried out a logistic regression, including in the model variables significant as univariate predictors of interest in eHealth. eHealth interest was recorded as a dichotomous outcome: no interest versus interest. We included a neutral midpoint in the ‘interest’ group, as we specifically wished to understand those people who expressed definite disinterest.

As part of the questionnaire, participants were asked a single open-ended question, ‘Do you have any concerns about eHealth?’ Open-ended responses were transferred verbatim to an Excel worksheet where inductive coding, using constant comparison to develop a code list that was inclusive of all data, and thematic analysis were performed by JP. A second author, DM, challenged the final thematic map and no discrepancies were noted. Trustworthiness was enhanced as DM is recognised as an expert in the field of polypharmacy in multimorbidity with a strong interest in the use of eHealth to improve patient care. Data units were identified then like codes were grouped together and themes were names. To demonstrate trustworthiness and authenticity, we include direct quotes in the results.

Results

The response rate to the questionnaire was estimated at 70%, using a 2-day sample where eligible patients declining participation were recorded at all sites. A total of 693 surveys were completed and returned. There were very little missing data for any response category (<5%) except in the item, ‘Access to internet linked devices and Wi-Fi’ (11%). Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in table 1, along with the demographics of the MUSIC practice-based research network adult patient population. The study sample included more women and participants from the older age bands than the MUSIC population demographic, consistent with the higher primary care attendance of these groups.18 The aim of ensuring an adequate sample of older adults was met as 270 (40%) participants were aged >60 years, with 135 (20%) of these aged 70 and over.

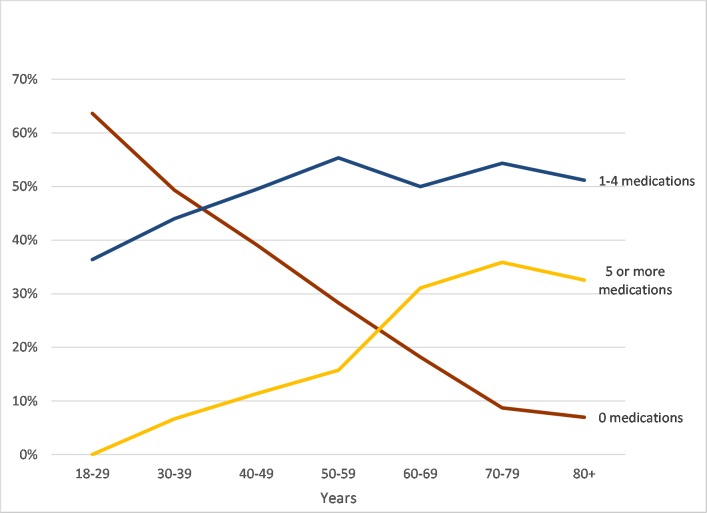

The proportion of respondents reporting use of >5 medications increased substantially and significantly with age (see figure 1): 33% (88/267) for those 60 years old and over compared with 10% (41/408) for those under 60 (risk ratio (RR) 3.3; 95% CI 2.4 to 4.7; p<0.001). Therefore, those aged 60 years and over are three times as likely to be on >5 medications compared with those under age 60. This is consistent with the known association between increasing multimorbidity with age,15 19 but illustrates the lack of complete overlap between groups.

Figure 1.

Relationship between age and medication number. Data are shown from 2014 to 2015. The graph indicates the relationship between a participant’s age and number of medications taken. The x-axis indicates age and the y-axis indicates the proportion of the study population. The red line indicates participants taking 0 medications, the blue line indicates participants taking 1–4 medications and the yellow line indicates participants taking five or more medications.

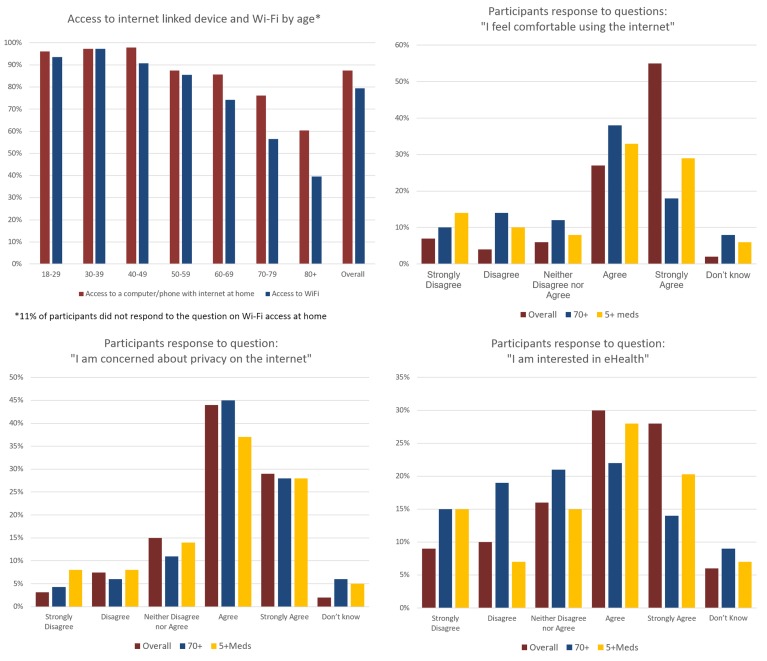

The majority of respondents reported access to the internet at home (87%), although this declined significantly with age (p<0.001). Patterns of access are illustrated in figure 2. While in younger age groups, those who had internet access also had access to Wi-Fi; this was not the case in older age bands. Seventy-six per cent (70/92) of those aged 70–79 had access to a computer/phone with internet in their home; however, only 57% had access to Wi-Fi while 60% (26/43) of seniors aged 80 and over have access to a computer/phone with internet in their home, and 40% (17/43) of that age category had access to Wi-Fi. Participants who were on five or more medicines had less access to Wi-Fi than participants on less than five (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.77 to 0.95; p<0.001.)

Figure 2.

Survey analysis results. Data are shown from 2014 to 2015. The graph on the top left represents the association between access to internet-linked device at home, such as a phone or computer, and Wi-Fi according to age band. The x-axis indicates age band and the y-axis indicates proportion of the defined age band expressed as a percentage. The red bar indicates access to a computer/phone with internet at home and the blue bar indicates access to Wi-Fi. The graph on the top right represents the association between comfort using the internet, and the two study subpopulations of interest: those aged 70 years and over, and those taking five or more medications. The x-axis represents the response categories for the statement, ‘I feel comfortable using the internet’. The y-axis indicates proportion, expressed as a percentage of the relevant study (sub) group. The red bar represents the overall study population. The blue bar represents those aged 70 and over. The yellow bar represents those taking five or more medications. The graph on the bottom left represents the association between participants concern about privacy on the internet and the two subpopulations of interest: those aged 70 years and over, and those taking five or more medications. The x-axis represents the response categories for the statement, ‘I am concerned about privacy on the internet.’ The y-axis indicates proportion, expressed as a percentage of the relevant study (sub) group. The red bar represents the overall study population. The blue bar represents those aged 70 and over. The yellow bar represents those taking five or more medications. The graph on the bottom right represents the association between participant’s interest in eHealth overall and in the two subpopulations of interest. The x-axis represents the response categories for the statement, ‘I am interested in eHealth.’ The y-axis indicates proportion, expressed as a percentage of the relevant study (sub) group. The red bar represents the overall study population. The bar represents those aged 70 and over. The yellow bar represents those taking five or more medications.

Figure 2 shows the range of responses to the statement, ‘I feel comfortable using the internet.’ The graph shows overall proportions, together with the prespecified subgroups: patients age 70 and over, and those reporting taking five or more medications. Eighty-two per cent (538/660) of the overall sample that responded to the question indicated they felt comfortable using the internet and comfort using the internet decreased with age. Those under 70 are more comfortable using the internet than those aged 70 and over, using the measure ‘strongly agree/agree’ with the statement, ‘I feel comfortable using the internet’ (RR 1.55; 87% vs 56%; 95% CI 1.33 to 1.83; p<0.0001). The group of respondents currently taking less than five medications was also more comfortable using the internet than those taking five or more medications, RR 1.38 (86% vs 63%; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.60), though not to the same degree as those aged 70 and over. Figure 2 shows respondents’ interest in eHealth. Fifty-eight per cent (381/659) of the participants expressed an interest in eHealth (‘Strongly Agree’ or ‘Agree’), while 20% (129/656) expressed disinterest in eHealth (‘Strongly Disagree’ or ‘Disagree’); 23% (146/656) responded that they did not know or felt neutral, and 5% (66/693) did not answer the question. Participants on five or more medications were significantly less likely to express interest in eHealth than those on less than five medications (RR 0.78; 47.2% vs 60.2%, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.96). Respondents aged 70 and older were also less likely to be interested in eHealth than those below age 70 (RR 0.58, 36% vs 63%, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.74). Participant SES was defined by linking participant’s postal code to median area income (Canadian census 2016 data is the most recent available). We found no association between participant’s interest in eHealth and income level (p=0.38). There was no association between income and concern about privacy (p=0.45) or comfort using the internet (p=0.95).

We were interested in the influence of different variables on patient interest in eHealth. We carried out a logistic regression, including variables significant as univariate predictors of interest in eHealth (age, use of 5+ long-term medications, home internet access, comfort using internet, privacy concerns, self-rated health). Table 2 shows the results of this analysis, which found internet access at home was significantly associated with interest in eHealth, while taking five or more long-term medications was a significant negative predictor of interest in eHealth (p=0.007; exp B 0.61 95% CI 0.43 to 0.87). There was no suggestion of a strong influence from any other particular variable (minimum p=0.11).

Table 2.

Predictors of interest in eHealth

| Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | Sig | ||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| Access to internet at home | 2.992 | 1.684 | 5.314 | <0.001 |

| Comfort using the internet | 1.009 | 0.989 | 1.029 | 0.373 |

| Privacy concerns | 1.010 | 0.991 | 1.028 | 0.308 |

| Self-rated health | 0.834 | 0.666 | 1.044 | 0.114 |

| More than five medications | 0.614 | 0.430 | 0.877 | 0.007 |

| Age | 0.896 | 0.780 | 1.029 | 0.119 |

Figure 2 shows the patient perspectives on privacy in the use of the internet specifically for the purpose of eHealth. Patients were asked whether they had privacy concerns around internet use related to eHealth. There were concerns about privacy raised by participants from all age groups. Nearly three-quarters (73%, 480/660) of all participants that responded to the question on privacy concerns indicated they were concerned about privacy relating to eHealth. There was no significant difference in concerns between respondents aged 70+ and those under 70 (RR 1.01, 73% vs 72%, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.14). Participants on five or more medications were less concerned about privacy on the internet than those on fewer medications (64% vs 75%, RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99).

Qualitative analysis

The two main themes present in free text comments were concerns about privacy of medical records in general and the loss of human connection/interaction and communication with clinicians. Some patients were pleased about the introduction of eHealth writing, ‘Why has it taken so long to implement such a system?’ Key themes and illustrative quotes are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Quotes illustrating main themes in free text response question

| Primary themes | |

| Concerns about privacy of medical records in general |

|

| The loss of human connection/interaction and communication with clinicians |

|

| Secondary themes | |

| A lack of understanding of what eHealth is and how it is used |

|

| Inclusiveness and cost if patients need to purchase new technology to be included |

|

| Concerns about accuracy based on eHealth system errors already experienced (eg, double bookings in online appointments) |

|

| Cost to tax payer/previously inefficient system |

|

Discussion

Main findings

We found significant differences in responses in our groups of interest: older age groups and in those on five or more medications. These groups were less comfortable using the internet and had less access to the tools required to engage with eHealth.

In univariate analyses we found that age, use of 5+ long-term medications, home internet access, comfort using the internet, privacy concerns and self-rated health were all associated with interest in eHealth. In the multivariate analysis, only two associations remained significant: internet access (vs no internet access at home) had a significant positive association with interest in eHealth, as might be expected, while multimorbidity was a significant negative predictor.

As indicated by the quantitative findings, and supported by the free text comments, participants had privacy concerns around eHealth. Our findings are consistent with recent literature indicating older adult’s distrust of eHealth leads to refrained use.9 Privacy has also been found to be less of a concern around appointment scheduling only, where 63% of participants were not concerned with privacy around emailing appointment information, although a quarter of them still did hold serious concerns.20 The willingness of patients to be contacted via email for appointment times did not vary significantly with patient age.20 A recent scoping review suggested that privacy concerns around personal health records are not high and can be reduced by positively framed explanations.2 Our findings showed that privacy concern among patients with multimorbidity is lower than those without multimorbidity.

Patients also expressed concerns surrounding impacts on relationship-based care. Our findings are consistent with other literature in this area: two studies using focus groups and semistructured interviews with older adults found older adults associated the use of eHealth with increased social isolation, loss of necessary visits and a reduction in quality of care due to less face-to-face interactions.10 11 This is an important domain to consider in evaluating interventions related to eHealth in primary care, where patient-centred care is a key function shown to support improved health outcomes, and in multimorbidity where a patient-centred approach to care is essential in integrating management of multiple chronic illnesses.21

Strengths

This study’s strength is its routine primary care setting, reflecting the population that attends primary care appointments and is most likely to be exposed to eHealth initiatives. We found, as expected, that the proportion of patients taking five or more medications increased with age. The proportion of patients with multimorbidity appeared lower in the non-senior age groups than other studies have described12—this may be related to differences in the population, or our criteria of five or more medications as a proxy measure for multimorbidity.

Limitations

While the response rate was reasonable, it is possible that the respondents do not represent the population from which they were sampled: there may be selection bias as the research assistants noted that almost half of non-respondents indicated they did not have internet access and for that reason did not want to complete the survey despite encouragement. It is therefore likely that we overestimate internet access in this population. Postal code mapping is a blunt tool for estimating SES. While the sample represented a wide sociodemographic range, the results may not be generalisable to other jurisdictions. It is also possible that a larger sample size would reveal more nuanced predictions within the model; however, no other variables approached a level of significance suggesting influences as important as multimorbidity. The use of only one coder is a limitation in our qualitative analysis of the question that invited free text responses.

Implications

Our finding of a negative association between multimorbidity and interest in eHealth has important implications for programme uptake and effectiveness in this group as well as health equity. This builds on previous qualitative studies identifying potential issues for patients with multimorbidity. Our findings add important quantitative data on the range and extent of patients’ perceptions of, and interest in engaging in, eHealth.

The majority of adult Canadians (60%) do not have the necessary skills to manage their health adequately.22 Canadians with the lowest health-literacy skills are 2.5 times more likely to report being in fair or poor health compared with those with the highest skill levels, even after correcting for factors such as age, education and gender.22 In a healthcare environment moving towards eHealth initiatives as an approach to chronic disease management, this will be compounded by our findings that show that multimorbidity was significantly associated with less interest in eHealth, less access to the internet and less comfort using computers and the internet.

It is unclear whether the relationship we saw between multimorbidity and less interest in eHealth relates to the illnesses themselves, disadvantage or to the increased general, physical and cognitive complexity that comes with managing multimorbidity. The absence of any signal of a significant relationship with self-rated health suggests it is more likely to reflect the burden of disadvantage, and the burden of treatment for patients with multimorbidity. Single disease approaches to multimorbidity mean care is complex and can be chaotic.23 eHealth may add additional burden to the already complex lives of those with multimorbidity, and increased complexity can compromise healthcare and quality of life, as seen in the effects of polypharmacy on compliance.23

Those considering developing and implementing eHealth strategies for chronic illness need to take into account these issues, in order that eHealth strategies and projects support reduction in health inequity, and are effective in their aim of improving overall quality of life and health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jill Berridge and Kathy De Caire for facilitating the survey administration at the clinics and to the doctors, nurses, allied health professionals and patients of the McMaster University Sentinel and Information Collaboration and the McMaster Family Health Team for their willingness to contribute their time and thoughts. Thanks to Ric Angeles for assistance with analysis, Dawn Elston for assistance with survey implementation, Melissa Pirrie for helpful comments on the manuscript and Patricia Habran-Dietrich for formatting and proofreading.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: DM conceived the research study and was responsible for overall design. OK, VB and SO designed and piloted the survey with supervision from DM and JP. OK collected the data. JP inputted the data and carried out the data analysis with DM. DM, JP, GA, SO and VB reviewed the manuscript and made final edits.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board. Project #14-501.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. eHealth report by the secretariat. Fifty-eighth world health assembly. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Archer N, Fevrier-Thomas U, Lokker C, et al. . Personal health records: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:515–22. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Starfield B, Gérvas J, Mangin D. Clinical care and health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health 2012;33:89–106. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ 2009;339:b2803 10.1136/bmj.b2803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tudor Hart J. The inverse care law. The Lancet 1971;297:405–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perera G, Holbrook A, Thabane L, et al. . Views on health information sharing and privacy from primary care practices using electronic medical records. Int J Med Inform 2011;80:94–101. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canada S. Online activities of Canadian boomers and seniors. 2014. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2009002/article/10910-eng.htm (Accessed 15th Jan 2016).

- 8. Smith A. Older adults and technology use: pewresearch center. 2014:1–28.

- 9. Zulman DM, Jenchura EC, Cohen DM, et al. . How Can eHealth technology address challenges related to multimorbidity? perspectives from patients with multiple chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1063–70. 10.1007/s11606-015-3222-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steele Gray C, Miller D, Kuluski K, et al. . Tying eHealth Tools to Patient Needs: Exploring the Use of eHealth for community-dwelling patients with complex chronic disease and disability. JMIR Res Protoc 2014;3:e67 10.2196/resprot.3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Runz-Jørgensen SM, Schiøtz ML, Christensen U. Perceived value of eHealth among people living with multimorbidity: a qualitative study. J Comorb 2017;7:96–111. 10.15256/joc.2017.7.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, et al. . Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e12–21. 10.3399/bjgp11X548929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras ME, et al. . A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:142–51. 10.1370/afm.1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, et al. . A protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial using the health teams advancing patient experience: strengthening quality (Health TAPESTRY) platform approach to promote person-focused primary healthcare for older adults. Implement Sci 2016;11:49 10.1186/s13012-016-0407-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. . Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics for Public Health. Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version. 3.03a version, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.IBM. SPSS statistics for windows [program]. 22.0 version. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I, et al. . Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003320 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyd CM, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010;32:451–74. 10.1007/BF03391611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seth P, Abu-Abed MI, Kapoor V, et al. . Email between patient and provider: assessing the attitudes and perspectives of 624 primary health care patients. JMIR Med Inform 2016;4:e42 10.2196/medinform.5853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mangin D. The contribution of primary care research to improving health services : Goodyear-Smith F, Mash B, International perspectives on primary care research. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Council on Learning. Health literacy in Canada: a healthy understanding. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Learning, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mangin D, Heath I, Jamoulle M. Beyond diagnosis: rising to the multimorbidity challenge. BMJ 2012;344:e3526 10.1136/bmj.e3526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.