Abstract

Introduction

Physical exercises have been recommended to improve the overall well-being of patients with fibromyalgia, with the main objective of repairing the effects of lack of physical conditioning and of improving the symptoms, especially pain and fatigue. Although widely recommended and widely known, few studies support the use of Pilates as an effective method in improving the symptoms of the disease, comparing it with other well-founded exercise modalities. This protocol was developed to describe the design of a randomised controlled study with a blind evaluator that evaluates the effectiveness of mat Pilates, comparing it with aquatic aerobic exercises, in improving pain in women with fibromyalgia.

Methods

Sixty women aged 18–60 years with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, with a score of between 3 and 8 points on the Visual Analogue Scale for pain, and who sign the clear and informed consent form will be recruited according to the inclusion criteria. They will be randomised into one of the two intervention groups: (1) Pilates, to perform an exercise programme based on mat Pilates; and (2) aquatic exercise, to participate in a programme of aerobic exercises in the swimming pool. The protocol will correspond to 12 weeks of treatment, with both groups performing the exercises with supervision twice a week. The primary outcome will be pain (Visual Analogue Scale for pain). The secondary outcomes are to include impact related to the disease, functional capacity, sleep quality and overall quality of life. The evaluations will be performed at three points: at baseline and after 6 weeks and 12 weeks of treatment.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of FACISA/UFRN (number: 2.116.314). Data collection will begin after approval by the ethics committee. There will be prior contact with the women, at which time all the information about the study and the objectives will be presented, as well as resolution no 466/2012 of the National Health Council of Brazil for the year 2012, which provides guidelines and regulatory standards for research involving human beings. Participants must sign the informed consent form before the study begins.

Trial registration number

Keywords: chronic pain, therapeutic exercise, aerobic exercise, pilates, fibromyalgia treatment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a pioneering study to evaluate the effectiveness of mat Pilates, comparing it with aquatic aerobic exercises, with a follow-up of 12 weeks.

In addition, implementation of the protocol in question may contribute to elucidating the effects of mat Pilates in women with fibromyalgia, as well as the frequency and the adequate duration of exercise to improve symptoms.

It is important to compare an exercise mode known as Pilates with another type of exercise, namely aerobic exercise, this time performed in the water, as less high-quality evidence on its use exists.

It is necessary that new exercise interventions for fibromyalgia be tested and compared so that they can be recommended based on evidence.

It is difficult to perform a double-blind study with exercises since participants know what exercise is being performed.

Background

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome characterised by generalised chronic pain and sleep disturbance, fatigue, reduced muscle strength, depression, anxiety, mood disorders, irritable bowel and other symptoms, which negatively impact quality of life.1–3 The prevalence of FM ranges from 0.66% to 4.4%, being more frequent in women than in men, with a proportion of 8 to 1, especially in the age group between 35 and 60 years. In Brazil, FM was considered the second most frequent rheumatic disease in outpatient clinics after osteoarthritis.4

The causes of the onset of this syndrome have not yet been fully elucidated. However, recent scientific research suggests that changes in metabolism and regulation of certain substances of the central nervous system, such as serotonin and norepinephrine, can trigger the disease.5

With a controversial aetiopathogenesis, the cause of FM is associated with genetic, environmental and neuromodulatory factors.6 Many patients with FM have high levels of stress and feelings of depression, anxiety and frustration.7 Patients feel fatigue and physical tiredness, with loss of energy and decreased strength when performing physical exercises. This fatigue leads to a great decrease in quality of life and often prevents the performance of activities of daily living, thereby reducing productivity in the work environment.

Physical exercises have been recommended to improve the overall well-being of women with FM, with the main purpose of repairing the effects of a lack of physical conditioning and improving the symptoms, especially pain and fatigue. Valim et al 8 report that physical exercises for FM are beneficial and low cost, and promote improvement in pain and other symptoms of the disease.8

The importance of physical exercise among women with FM is already well described in the literature, in addition to it being a low-cost, safe and efficient treatment intervention. Exercises have also been shown to be effective in reducing pain and the number of painful points, and improving quality of life, mood and other psychological aspects. Although studies show benefits in almost all exercise modalities, further evidence supports the practice of aerobic training.9 10 Within this perspective, a Cochrane review on aquatic exercises for FM showed that these exercises are effective in improving physical well-being, functional capacity and pain, and results in a 37% improvement in muscular strength and improvement in cardiovascular capacity.11

The Pilates method of exercising has been gaining popularity, being considered one more exercise modality that can be used. This method, developed by Joseph H Pilates, includes stretching and strengthening exercises with controlled and precise movements where special equipment can be used or which can be performed even on the ground. The purpose of physical training using Pilates is to improve body functioning based on core strengthening, a term that refers to the centre of the trunk supporting the body (rectus abdominis, transverse abdomen, erector spine, diaphragm and pelvic floor muscles). The six basic principles of the method are centralisation, concentration, control, precision, respiration and flow.12

Although highly recommended and widely known, few studies have evaluated the effects of this method on the treatment of women with FM. In addition, these studies present several methodological flaws that compromise their results and suggest that studies with better methodological design should be conducted with the objective of observing the effectiveness of Pilates in treating patients with FM.13 14 Therefore, the main objective of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of mat Pilates in improving pain in women with FM and compare it with aquatic aerobic exercises. Our hypothesis is that mat Pilates can also bring benefits by improving pain in women with FM, similar to aquatic aerobic exercises. The secondary objectives of the study are to compare the impact on the disease, functionality and performance, sleep quality, and quality of life of women with FM who perform two different modalities of exercise.

Methods

Design

This is a study protocol for a randomised controlled, parallel-group, single-blind trial. Participants will be randomised to perform mat Pilates or aerobic exercises. Allocation to either group (mat Pilates or aquatic aerobic exercises) will be achieved through a computer-generated sequence of random numbers. The allocation sequence will be created and carried out by a non-interventionist researcher in charge of telephone screening and handling of data obtained from various assessment sessions.

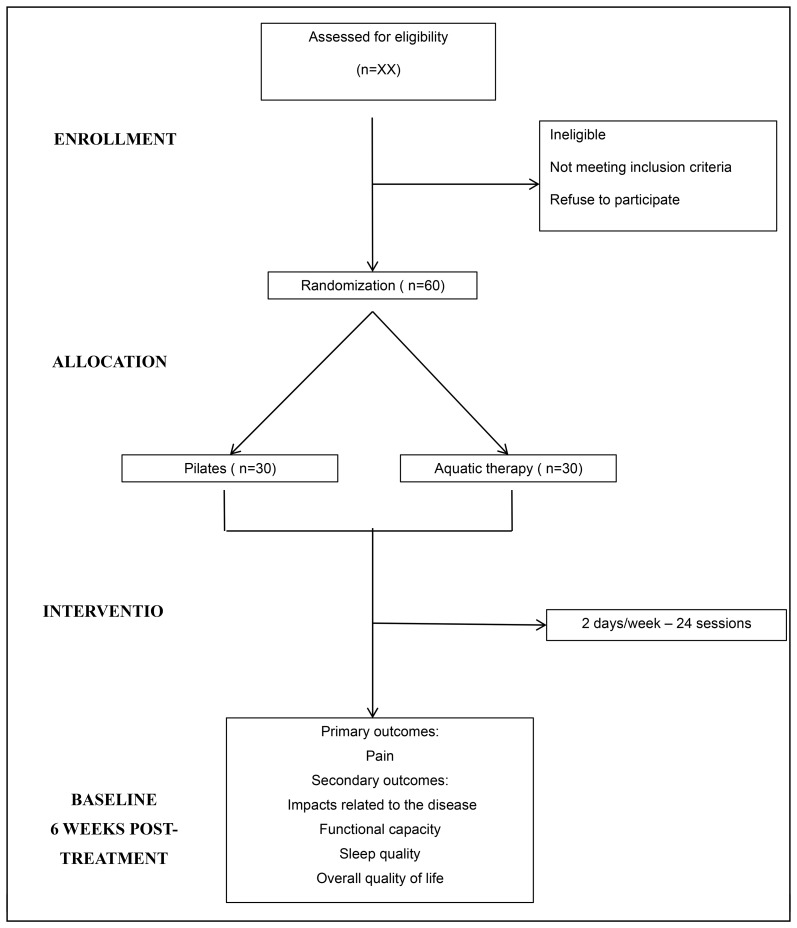

Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the progress of the various stages of this test.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Participants

Sixty women aged 18–60 years with a clinical diagnosis of FM according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology15 and a score between 3 and 8 points on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain will be recruited, provided they give their consent after being informed of the study’s objectives and procedures. The volunteers will be recruited from the waiting list of patients of the Physiotherapy School Clinic of the Faculty of Health Sciences of Trairi, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (FACISA/UFRN); in addition, the project will be announced by radio and local media. After this, a telephone contact will first be made to clarify any questions from the participants, and the first screening for inclusion will be carried out.

Personal data of the participants will be numerically coded and stored in a database, which can only be accessed by the researcher responsible for the randomisation and blinding process. Informed consent as well as all study information will be passed on to all participants. Prior to any data collection, participants must sign the clear and informed consent form.

Inclusion criteria

Women diagnosed with FM according to the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.

Aged between 18 and 60 years.

Reporting pain between 3 and 8 on VAS.

Exclusion criteria

Uncontrolled hypertension.

Decompensated cardiorespiratory disease.

History of syncope or arrhythmia induced by physical exercise.

Decompensated diabetes.

Serious psychiatric illness.

Primarily systemic exertion intolerance disease.

Thyroid issues.

Obesity.

History of regular exercise (at least two times a week) in the last 6 months.

Any other condition that makes it impossible for the patient to perform physical exercises.

Research team

This study will involve five researchers: one researcher responsible for the evaluations, two researchers responsible for the interventions (one for each group), one researcher responsible for the interview, initial screening and randomisation of participants, and one researcher who will perform the statistical analysis.

Patient and public involvement

The main question of the study was developed to answer a gap in the literature on the comparison of different physical exercise modalities for treating FM, although no participant in the study has been involved so far. The results will be disseminated to the participants in the form of a lecture and fellowship at the end of the study, presenting the effects found in the studied variables. If one modality is proven to be superior over the other, it will be offered and guaranteed to the participants.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants who are successfully approved for screening and who agree to sign the free and informed consent form will receive a number in a randomisation table according to the inclusion order in the study. These numbers will correspond to the Pilates group or aquatic exercise group in which volunteers will be included. This distribution will be performed randomly through the website randomization.com. The allocation will be concealed using sealed and opaque envelopes, numbered consecutively. An independent researcher who will not participate in the other study procedures will perform the randomisation process. The flow diagram of the study is shown in figure 1.

The researchers responsible for interventions will be blinded to participants’ initial assessments, and the researcher responsible for evaluations will not know the group of each participant.

In addition, data collected during participant evaluations will not be revealed to the researchers responsible for interventions, and participants will be instructed not to disclose their experience and information related to the intervention.

Finally, the researcher responsible for statistical analysis will be blinded. Once the intervention is completed, he/she will receive an Excel data table with all the necessary data without identification of the subjects or the groups.

Interventions

Participants in this study will receive 24 treatment sessions (2 per week) for 12 weeks. Evaluations will be performed prior to the start of treatment, after 12 sessions and after 24 treatment sessions.

Mat Pilates exercise programme

The exercise programme based on Pilates will be carried out on a mat in a group room of the Physiotherapy School Clinic of the FACISA/UFRN in Santa Cruz, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. The room has ample space and air conditioning for better patient accommodation. The exercises will be performed twice a week for 12 weeks. Each session will last about 50 min and will be supervised by an experienced mat Pilates researcher who will be responsible for the intervention in this group. Table 1 shows the progression of the exercises according to time. A total of 10 exercises will be performed, which are presented in table 2.

Table 1.

Exercise progression according to intervention time

| Period | Dose |

| First month (1st–8th session) | 1 set of 8 repetitions |

| Second month (8th–16th session) | 2 sets of 10 repetitions |

| Third month (16th–24th session) | 3 sets of 8 repetitions |

Intervention group exercise programme.

Table 2.

Mat Pilates group exercise programme

| Name of the exercise | Description |

| 1. Swan Stretches the anterior trunk chain. Strengthens the pectoral, triceps and anterior deltoid muscles. |

|

| 2. One leg up-down Strengthens the rectus femoris, iliopsoas and sartorius muscles. |

|

| 3. Leg circles Strengthens the rectus femoris, sartorius, adductor and gluteus medius muscles. |

|

| 4. Single leg stretch Strengthens the abdomen, and stretches the glutes and the lumbar spine. |

|

| 5. Saw Stretches the trunk rotators, the hamstrings and the quadratus lumborum muscles. Strengthens the rectus abdominis, external and internal oblique muscles. |

|

| 6. Side kicks: front and back Strengthens the rectus femoris, iliopsoas, sartorius, gluteus medius, gluteus maximus and abdominal muscles in isometry. |

|

| 7. The hundred Strengthens the abdominal, oblique, transverse and rectus femoris muscles. |

|

| 8. Pelvic lift on the ball Strengthens the gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus, gastrocnemius and quadriceps femoris muscles. Mobilises the spine. |

|

| 9. Sit-ups on the ball Strengthens rectus abdominis and external oblique muscles. |

|

| 10. Stretching on the ball Stretching and muscle relaxation. |

|

Aquatic aerobic exercise programme

The aerobic exercise programme will be carried out in the therapeutic swimming pool of the Physiotherapy School Clinic of the FACISA/UFRN in Santa Cruz, Rio Grande do Norte. The pool is heated (30°C), which provides better effects to the proposed treatment.

The exercises will be performed twice a week for 12 weeks. Each session will last about 50 min and will be supervised by an experienced researcher responsible for the intervention in this group.

Patients will always be instructed to perform the exercise according to their current conditioning and increase the intensity according to their perception of exertion (Borg Scale). The programme is best described in table 3.

Table 3.

Aquatic aerobic exercises group exercise programme

| Time | Exercise |

| 5 min—warm-up. |

|

| 30 min—aquatic aerobic exercises. |

|

| 5 min—cool-down. |

|

Evaluations

During the baseline measurement, the following descriptive characteristics will be collected: gender, age, weight, height and current occupation. The chronology of the evaluation of the primary and secondary outcome measures is shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Chronology of primary and secondary outcome measures

| Results | Baseline | 6 weeks | 12 weeks |

| Primary | |||

| VAS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Secondary | |||

| FIQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| TUG | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 6MWT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PSQI-BR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ESS-BR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| SF-36 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

6MWT, Six-Minute Walk Test; ESS-BR, Epworth Sleepiness Scale-Brazilian Portuguese version; FIQ, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; PSQI-BR, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index-Brazilian Portuguese version; SF-36, Short Form-36 Health Survey; TUG, Timed Up and Go test; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale for pain.

Primary outcome measures

VAS for pain is the main result of this study and will be used to rate the intensity of pain. Participants should mark the intensity of their pain on the VAS, which consists of a horizontal line 100 mm long, where 0 means ‘no pain’ and 10 ‘worst pain imaginable’, where the participant reports the most intense pain episode during the daily activities. The difference considered clinically significant for improvement in pain is a change in the scale by 2.5 cm.16

Secondary outcome measures

Impact related to the disease. The evaluation will be performed using the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire, a questionnaire that assesses anxiety, depression and physical performance in FM. The translated version adapted for the Brazilian population will be used.17

- Functional capacity.

- ‘Timed Up and Go test’, a functional test consisting of getting up from a chair without the aid of the arms, walking a distance of 3 m, turning around and walking back. At the start of the test, the patient should have his or her back resting on the back of the chair. The patient then receives the ‘go’ command to perform the test and they are timed from the command voice until the moment they rest their back on the chair again.18 19

- Six-Minute Walk Test, to measure the walking performance of patients. The test will be performed on a 20 m marked gymnasium track away from other people. The patients will be instructed to walk the entire distance, being able to interrupt the test if they do not feel able to continue.19

- Assessment of sleep quality.

- The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)-Brazilian Portuguese versionwill be used to evaluate the subjective quality of sleep. This questionnaire consists of 19 items grouped into 7 components which are scored on a scale from 0 to 3. The components are (1) subjective quality of sleep, (2) sleep latency, (3) duration of sleep, (4) habitual sleep efficiency, (5) sleep disorders, (6) use of medication for sleep and (7) daytime dysfunction. The values corresponding to respondents’ responses for each component are summed up to give an overall PSQI score which ranges from 0 to 21. Scores between 0 and 4 indicate good sleep quality, while scores of 5–10 indicate poor quality, and scores above 10 indicate sleep disturbance.20

- The Epworth Sleepiness Scale-Brazilian Portuguese version will be used to measure the possibility of dozing off. The questionnaire consists of eight daily situations where the probability of dozing off is graded on a scale from 0 (no probability of dozing off) to 3 (very likely to doze off). At the end, the scores are summed up to generate a total score ranging from 0 to 24, where an individual with a score above 10 points is characterised with excessive drowsiness.21

Overall quality of life will be assessed by the Short Form-36 Health Survey, a quality of life questionnaire, translated into Portuguese, containing 36 questions. The result is given in eight domains: physical functioning, role physical, role emotional, bodily pain, vitality, mental health, social functioning and general health, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 in each domain, in which 100 is the best health state and 0 the worst health state.22

Training of researchers

A series of training stages for assessment and treatment will be implemented prior to the start of the study intending to standardise the actions carried out in the study. In these training stages, treatment techniques and measurement will be practised to reach a consensus among the involved researchers.

Statistical issues

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated based on the pain variable in order to find a difference of ±2.5 points on VAS between the intervention groups,16 with an SD of 2.5 points.23 A sample of 60 participants is required (30 in each group) to achieve a statistical power of 90% with a 5% alpha and considering a loss rate of 20%. The sample calculation was performed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical test with interaction between groups. G*Power V.3.1 was used for calculation.

Statistical analysis

The analysis will be descriptive for all outcomes included in the study, expressing quantitative outcomes with their mean±SD and qualitative outcomes with their absolute value, percentage and 95% CIs.

Data will be analysed by SPSS V.22.0 software. The χ2 test will be used to observe the associations between the qualitative variables. After observing the normal distribution and homogeneity of the variances of the quantitative variables by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Levene test, respectively, the Student’s t-test (for variables with normal distribution) or the Mann-Whitney test (for variables with a non-normal distribution) will be used to perform a comparison of the means. Estimates of the average effect (differences between groups) for all variables will be calculated using the ANOVA mixed model. This analysis model incorporated the intervention groups (Pilates and aquatic exercise), time (baseline, 6 weeks and 12 weeks) and the group × time interaction. When a significant F value is found, the Bonferroni post-hoc test will be applied to identify the differences. An intention-to-treat analysis will be used to assess the response to intervention, with the last evaluation carried forward used when necessary. The size of the effect between the groups for the variables that present intergroup differences can be calculated at some point, with a respective 95% CI. The level of statistical significance adopted will be 5%. The analysis will be performed by an independent researcher.

Discussion

This protocol will be carried out as a randomised, single-blind clinical trial to investigate whether mat Pilates produces beneficial effects similar to aquatic aerobic exercises in reducing pain and disability in women with FM. The secondary outcomes are to include impact related to the disease, functional capacity, sleep quality and overall quality of life. With the conclusion of the study, we hope to test the following null hypothesis: ‘There is no difference in pain and disability for participants undergoing treatment with mat Pilates or with aquatic aerobic exercises’.

Women with FM experience fatigue24 and physical tiredness, with loss of energy and decreased power/strength when performing physical exercises. Fatigue leads to a great decrease in quality of life and often prevents performance of activities of daily living, thereby reducing productivity in the workplace. Thus, physical exercises, and especially aerobic exercises,25 have been recommended to improve the overall well-being of women with FM, with the main purpose of repairing the effects of a lack of physical conditioning, and especially improving the symptoms of pain and fatigue.

A recent Cochrane review on aerobic exercise in FM concluded that moderate-quality evidence exists indicating that aerobic exercise is likely to improve quality of life when compared with control, and poor-quality evidence suggests that aerobic exercise may slightly decrease pain intensity, slightly improve physical function and lead to a slight difference in fatigue and stiffness.26

With regard to aquatic aerobic exercises, a meta-analysis27 found good results for aquatic therapy (hydrotherapy) with a duration of over 20 weeks; however, in our study, we will use aquatic exercises with an aerobic purpose, rather than just aquatic physiotherapy. Deep water running is an aquatic aerobic conditioning technique that has shown to be as beneficial as aerobic exercise on land, however with advantages related to emotional aspects in women with FM.28 A systematic review carried out by Bidonde et al 11 concluded that low to moderate quality of evidence in relation to the control suggests that aquatic training is beneficial in improving the well-being, symptoms and fitness in adults with FM. Low-quality evidence suggests that aquatic and land exercises have benefits, except for muscle strength (low-quality evidence favouring land exercises), and also that no serious adverse effects were found.11

A recent protocol on aquatic exercise versus land exercises to treat balance and pain in women with FM was published, showing the interest of the researchers in deepening knowledge on the subject, since more well-designed studies are still necessary. However, our aquatic aerobic exercise programme differs from the one used in this study due to the fact that it aims to work on more aspects related to balance and proprioception in water.29 Pilates is currently well known and highly recommended by doctors and health professionals with the aim of improving pain, posture, stretching and strengthening of the body as a whole. Women with FM are frequently recommended to perform physical exercises to improve FM symptoms, and Pilates is an important option to be considered. However, few studies have evaluated the effects of this method on the treatment of women with FM. In addition, these studies present several methodological flaws that compromise their results, suggesting that studies with better methodological design should be conducted with the objective of observing the effectiveness of Pilates in treating these women.13 14

Adherence to treatment is something very important to be reported, mainly in interventions for chronic musculoskeletal disorders.30 We hope that the volunteers in our study will have good adherence to treatment, considering that the heated pool is a stimulating invitation for relaxation and that Pilates is a popular, famous and still relatively high-cost technique in reality; thus, we believe that our intervention will be well accepted.

In view of the above, we hope that the conclusion of this study contributes to scientific knowledge, providing support for the use of physiotherapy as a safe and effective tool in treating women with FM, as well as helps elucidate the best frequency and adequate duration of exercise to improve symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants and to FACISA/UFRN and the research director (PROPESQ/UFRN Edital N° 01/2017) for the support given to the research.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: CAdAL and MCdS led the study design, and designed and planned the statistical analysis. HJdAS, TTXN, VPSdS and RTJC have made substantial contributions to the design of the study. HJdAS, CAdAL, MCdS, TTXN, VPSdS and RTJC reviewed the manuscript critically and gave final approval for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Faculty of Health Sciences of Trairi – (FACISA/UFRN) with registration code 2.116.314. The ethical principles agreed in the Declaration of Helsinki will be respected for all study procedures. Respect for individuals will be insured and their autonomy will be maintained. Participants will be informed of the study objectives, its risks and benefits. Participants will be free to abandon the study at any time without the obligation of giving any explanation. Participants must sign the informed consent before the study begins. This study protocol is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (a U.S. National Institutes of Health service) with the identifier NCT03149198, published on 11th May, 2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Gowans SE, Dehueck A, Voss S, et al. . Six-month and one-year followup of 23 weeks of aerobic exercise for individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:890–8. 10.1002/art.20828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Figueroa A, Kingsley JD, McMillan V, et al. . Resistance exercise training improves heart rate variability in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2008;28:49–54. 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2007.00776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Oliveira FS, de Almeida Silva HJ, de Pontes Oliveira JM, et al. . The sophrology as adjuvant therapy may improve the functionality of patients with fibromyalgia. A pilot randomized controlled trial. MTP RehabJournal 2016;14:386. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heymann RE, Paiva EdosS, Helfenstein Junior M, et al. . Consenso brasileiro do tratamento da fibromialgia. Rev Bras Reumatol 2010;50:56–66. 10.1590/S0482-50042010000100006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffman DL, Dukes EM. The health status burden of people with fibromyalgia: a review of studies that assessed health status with the SF-36 or the SF-12. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:115–26. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01638.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Talotta R, Bazzichi L, Di Franco M, et al. . One year in review 2017: fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35105:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hadlandsmyth K, Dailey DL, Rakel BA, et al. . Somatic symptom presentations in women with fibromyalgia are differentially associated with elevated depression and anxiety. J Health Psychol 2017:135910531773657 10.1177/1359105317736577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valim V, Natour J, Xiao Y, et al. . Effects of physical exercise on serum levels of serotonin and its metabolite in fibromyalgia: a randomized pilot study. Rev Bras Reumatol 2013;53:538–41. 10.1016/j.rbr.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Busch AJ, Barber KA, Overend TJ, et al. . Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:CD003786 10.1002/14651858.CD003786.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen L, Arendt-Nielsen S, et al. . EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:536–41. 10.1136/ard.2007.071522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, et al. . Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD011336 10.1002/14651858.CD011336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Natour J, Cazotti LA, Ribeiro LH, et al. . Pilates improves pain, function and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:59–68. 10.1177/0269215514538981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Altan L, Korkmaz N, Bingol U, et al. . Effect of pilates training on people with fibromyalgia syndrome: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:1983–8. 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ekici G, Unal E, Akbayrak T, et al. . Effects of active/passive interventions on pain, anxiety, and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia: Randomized controlled pilot trial. Women Health 2017;57:88–107. 10.1080/03630242.2016.1153017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, et al. . The American college of rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:600–10. 10.1002/acr.20140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farrar JT, Young Jr JP, LaMoreaux L, et al. . Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001;94:149–58. 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marques AP, Santos AMB, Assumpção A, et al. . Validação da versão brasileira do Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ). Rev Bras Reumatol 2006;46:24–31. 10.1590/S0482-50042006000100006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bennell K, Dobson F, Hinman R. Measures of physical performance assessments: Self-Paced Walk Test (SPWT), Stair Climb Test (SCT), Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Chair Stand Test (CST), Timed Up & Go (TUG), Sock Test, Lift and Carry Test (LCT), and Car Task. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:S350–S370. 10.1002/acr.20538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, et al. . Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med 2011;12:70–5. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SC, Hoff LS, et al. . Portuguese-language version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: validation for use in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol 2009;35:877–83. 10.1590/S1806-37132009000900009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, SantosW M I, et al. . Brazilian-Portuguese version of the SF-36 questionnaire: a reliable and valid quality of life outcome measure. Rev Bras Reumatol 1999;39:143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gustafsson M, Gaston-Johansson F. Pain intensity and health locus of control: a comparison of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Educ Couns 1996;29:179–88. 10.1016/0738-3991(96)00864-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morris S, Li Y, Smith JAM, et al. . Multidimensional daily diary of fatigue-fibromyalgia-17 items (MDF-fibro-17). part 1: development and content validity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:195 10.1186/s12891-017-1544-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, et al. . Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1. Phys Ther 2008;88:857–71. 10.2522/ptj.20070200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. . Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD012700 10.1002/14651858.CD012700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lima TB, Dias JM, Mazuquin BF, et al. . The effectiveness of aquatic physical therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:892–908. 10.1177/0269215513484772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Assis MR, Silva LE, Alves AM, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of deep water running: clinical effectiveness of aquatic exercise to treat fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:57–65. 10.1002/art.21693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rivas Neira S, Pasqual Marques A, Pegito Pérez I, et al. . Effectiveness of aquatic therapy vs land-based therapy for balance and pain in women with fibromyalgia: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:22 10.1186/s12891-016-1364-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sanz-Baños Y, Pastor-Mira MÁ, Lledó A, et al. . Do women with fibromyalgia adhere to walking for exercise programs to improve their health? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:2475–87. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1347722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.