Abstract

We use difference-in-differences models and individual-level data from the national and state Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) from 2005 to 2015 to examine the effects of e-cigarette Minimum Legal Sale Age (MLSA) laws on youth cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and marijuana use. Our results suggest that these laws increased youth smoking participation by about one percentage point, and approximately half of the increased smoking participation could be attributed to smoking initiation. We find little evidence of higher cigarette smoking persisting beyond the point at which youth age out of the laws. Our results also show little effect of the laws on youth drinking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Taken together, our findings suggest a possible unintended effect of e-cigarette MLSA laws—rising cigarette use in the short term while youth are restricted from purchasing e-cigarettes.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, vaping, alcohol, tobacco, smoking, marijuana, minimum legal sale age, tobacco control, youth, substitutes, complements, D12, I12, I18

1. Introduction

Teenage substance use remains a major public health concern. Substance use is linked with poor academic performance, impaired cognitive development, mental and physical health problems, and motor-vehicle accidents (National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2016). Tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol are among the most widely used substances by adolescents. Youth smoking rates are declining but each day more than 3,200 youth initiate cigarette smoking and more than 2,000 transition into daily smoking (US Department of Health Human Services 2014). Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug, with 22% of high school seniors reporting past month use. Moreover, alcohol use among youth is even more widespread than the use of tobacco or illicit drugs. Almost one out of three youth has consumed alcohol and almost one out of five has binged in the past month (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015).

E-cigarettes debuted in the U.S market in 2007 and have been advertised and positioned as alternatives to conventional cigarettes. Since its introduction, e-cigarettes have surged in popularity among youth.1 Within a four-year period (2011–2015), its use has increased from 1.5% to 16.0% among high school students and from 0.6% to 5.3% among middle school students, surpassing cigarettes as the most commonly used tobacco product among the underage population (Singh 2016).2

A heated policy debate concerning the regulation of e-cigarettes has ensued, at the heart of which are fundamental questions regarding the relative risks between e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes and the potential for e-cigarettes to serve as a tool towards tobacco harm reduction. The British government issued a report suggesting that e-cigarettes are no more than five percent as harmful as conventional cigarettes (Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians 2016) and other studies have suggested that e-cigarettes can direct smokers away from smoking and possibly help them quit (Hampton 2014, Abrams 2014, Brandon et al. 2015, McNeill et al. 2015). However, the 2016 Surgeon General’s Report warns that e-cigarettes are dangerous to youth because they can interfere with cognitive development and cause nicotine addiction (US Department of Health Human Services 2016). One particular concern is that e-cigarettes may act as a gateway towards the use of other addictive substances, such as cigarettes, marijuana, and alcohol (Gostin and Glasner 2014, Primack et al. 2015, Mammen, Rehm, and Rueda 2016). While the downward trend in youth smoking indicates a reduction in the number of new initiates, possibly because some of these youth are turning to e-cigarettes, it is not clear whether this trend is necessarily harm-reducing since youth who initiate nicotine with e-cigarettes may transition to smoking at some later point in time or to dual use. Polysubstance use is prevalent among youth, which may lead to further spillovers from tobacco use to the use of other substances like marijuana or alcohol.3

In response to the rising e-cigarette use, state governments passed a wave of regulations limiting youth access to e-cigarettes. A popular initiative has been the adoption of Minimum Legal Sale Age (MLSA) laws on e-cigarettes. In March of 2010, New Jersey became the first state to implement an e-cigarette MLSA law, followed by four other states later within the same year.4 Additional states adopted e-cigarette MLSA laws in each year subsequently, and by the time the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated a federal e-cigarette MLSA law of 18 in August of 2016, all states but two had an e-cigarette MLSA law in place.5

In this study we assess whether, and the extent to which, restricting youth access to e-cigarettes has affected their use of other addictive substances. We contribute to the limited literature on the effects of e-cigarette MLSA laws in several ways. First, the few studies that have explored the effect of such laws on youth smoking have arrived at mixed conclusions, and our study attempts to provide further clarity to this conflicting evidence base (Friedman 2015, Pesko, Hughes, and Faisal 2016, Abouk and Adams 2017). Second, we extend the prior work and provide the first evidence on the intertemporal relationship between e-cigarette MLSA laws and youth smoking. In addition to any contemporaneous effects, the laws may also have dynamic effects and our study informs whether a policy that makes vaping less attractive today makes future smoking more or less likely when youth are no longer subject to the MLSA-based restriction. As noted above, this intertemporal transition from vaping to smoking among youth has formed one of the key questions underlying the current policy debate. Third, we broaden the lens to a few other addictive substances and provide some of the first evidence on the potential spillover effects of the laws on other substances. Such spillover effects are plausible given the high co-occurrence of and transitions between alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use among adolescents.6

2. Relevant Studies

Individual states have made several efforts in recent decades to tighten tobacco control regulations by prohibiting retailers from selling tobacco products to minors. Several studies have examined the efficacy of cigarette MLSA laws adopted between the 1980s and early 1990s. Many suggest that the laws have been effective in reducing youth smoking (Chaloupka and Pacula 1998, Gruber and Zinman 2001, Ahmad and Billimek 2007, DiFranza, Savageau, and Fletcher 2009, Ertan Yörük and Yörük 2015), while some find the law’s impact being limited (Chaloupka and Grossman 1996, DeCicca, Kenkel, and Mathios 2002).

A few studies have focused specifically on the impact of e-cigarette MLSA laws. Friedman (2015) and Pesko et al. (2016), based on state-aggregated data spanning up to 2013, find that the laws increased youth smoking by 0.8 to 0.9 percentage points.7 Their results are consistent with e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes being economic substitutes, at least contemporaneously. In contrast, results in Abouk and Adams (2017) suggest complementarity between e-cigarettes and cigarettes among the 12th graders from the Monitoring the Future project spanning up to 2014. It is unclear whether the divergence in findings stems from the use of more granular individual-level data or from the addition of one more study period.8

Our study contributes to this limited literature in three important ways. First, we add to the thin evidence base by incorporating micro-level data from the national and the state YRBSS spanning up to 2015, yielding a sample size substantially larger relative to Abouk and Adams. Using data up to 2015, just prior to the FDA’s national ban on e-cigarette sales to minors, further maximizes policy variation and extends the post-policy window for the other states to disentangle the laws’ dynamic effects.9 Second-order policy responses on youth substance use (other than e-cigarettes) can be small, and hence micro-level data with large sample sizes, more cleanly-defined affected groups, and longer time windows with greater policy variation may be necessary for maximizing precision. Second, prior work has focused only on the contemporaneous effects of the e-cigarette MLSA laws on smoking. Our study is the first to consider how these laws may affect youth smoking once they have aged out of the restriction. This is particularly relevant for assessing the long-term effects on smoking and addressing public health concerns with respect to the intertemporal transition from e-cigarette use to cigarette smoking. Finally, we estimate whether the laws have had any spillover effects into the use of other addictive substances. With the exception of Pesko et al. (2016), who studied and found no effects on marijuana use, prior work has mainly focused on cigarette smoking.

3. Conceptual Framework

The effect of e-cigarette MLSA laws on smoking, drinking, and marijuana use depends on the marginal direct and indirect costs of youth obtaining e-cigarettes as well as the relationship between e-cigarettes and these other substances. Banning legal sales of e-cigarettes to minors is predicted to increase the indirect costs of obtaining the product through added inconvenience and/or associated time delays. The restriction could also increase the direct costs of obtaining the product through additional markups or youth paying “friends” to purchase the product for them. E-cigarette MLSA laws will therefore raise the full price of e-cigarettes, leading to first-order effects in the form of a decline in e-cigarette use.10 Any rise in the costs of purchasing e-cigarettes would cause a relative increase in the cost of e-cigarettes in comparison with conventional cigarettes, thereby affecting not just e-cigarette use (vaping) but also potentially shifting smoking behaviors.

The e-cigarette MLSA laws may impact dynamic transitions between vaping and smoking. Once a youth turns 18, he will be able to purchase both products legally.11 In states that have enacted an e-cigarette MLSA law, youth who age out of the laws will therefore experience a decrease in the relative cost of obtaining e-cigarettes, which could lead to an increase in vaping and a decrease in smoking. But, if youth had turned to smoking when exposed to the laws, the accumulated stock of nicotine may make it difficult to cut down on smoking even when they are able to purchase e-cigarettes legally.

The law’s effects on smoking are perhaps most highly indicated given the proximity between e-cigarettes and cigarettes, but the law may also have second-order effects on the use of other addictive substances. Many youth concurrently smoke, drink, and use marijuana (Moss, Chen, and Yi 2014), and changes in tobacco consumption can affect the marginal utility of consuming these other substances. Studies have explored this cross-relationship between smoking, drinking, and marijuana use, but the literature lacks a consensus.12 Ultimately the question of how e-cigarette MLSA laws impact smoking, drinking, and marijuana use cannot be settled based on theory alone, and we bring empirical evidence to bear on this issue.

4. Data

Our analyses draw on the pooled national and state Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS).13 Several studies note the advantages of using such pooled data over the national YRBSS alone, and we think it is especially well-suited for the analysis.14 For one thing, very few datasets have requisite sample sizes and contain information on smoking and substance use patterns among adolescents over the period when e-cigarette restrictions have been unfolding. The pooled YRBSS is one of the few that do, yielding sample sizes close to 800,000 person-year observations, which are 9 times larger than the national YRBSS and 15 times the MTF. Moreover, the pooled YRBSS maximizes the sample size for smaller states and thereby improves precision and state-trend controls. Most importantly, the policy effects we estimate are intention-to-treat (ITT) effects whose precision rely on sample sizes due to relatively low prevalence rates of youth substance use (smoking in particular), and that ITT estimates capture the average population effects. In that sense, large sample size will be necessary to reliably detect potentially small ITT effects. While some of these policy effects (for instance, on drinking or marijuana use) are third-order effects and would particularly benefit from large samples, it is important to precisely document null effects if they are statistically insignificant.

The YRBSS is conducted biennially and we utilize data from the most recent six waves spanning 2005 through 2015.15 The data collection process typically starts in March and ends in early June for each state, and our policy indicator for the e-cigarette MLSA law is therefore set to switch on (equal one) if the law has been effective by the end of February of the survey year and thereafter, and zero otherwise.16 We define the key outcome variables of interest (smoking, drinking, and marijuana use) using CDC’s benchmark (further details are available online). To isolate the ceteris paribus relationship between the laws and youth substance use, we control for an extensive set of policy controls that we also describe further online. We follow prior studies and use weights based on population, gender, race, and age at the state by year level retrieved from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program for all analyses (Anderson, Hansen, and Rees 2015).17

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all key variables over our study period, with their means weighted by the total underage population. Columns 1, 2, 3 present means for the full sample, the sample in which youth are younger than 18, and the sample where youth are 18 or older.18 As shown in Table 1, 17% of the sample are past-month smokers, 20% are marijuana users, 39% are past-month drinkers, and 23% have participated in binge drinking. Questions related to youth e-cigarette use are first included in the YRBSS in 2015, and using data from this wave, we find that 45% of high-school students have tried e-cigarettes in their lifetime and 24% are current (past 30-day) e-cigarette users. The final two columns present means of all variables during the pre-policy window, separately for states that have implemented e-cigarette MLSA laws at any time over our study period (MLSA or treated states) and states that have not yet done so (non-MLSA or control states). Baseline youth substance use rates are slightly higher among the control states (by about 2–3 percentage points, or about 10%), but their differences are not statistically significant.

Table 1 —

Summary Statistics of Key Response Variables, Individual Demographic Characteristics, and State-level Policy Controls

| Full Sample | Youth younger than 18 |

Youth 18 or older |

States with E-Cig MLSA Laws; Pre-policy periods |

States without E-Cig MLSA Laws; Pre-policy periods |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth substance use | |||||

| Current smoker | 0.17 [0.37] | 0.15 [0.36] | 0.25 [0.43] | 0.18 [0.39] | 0.20 [0.41] |

| Current drinker | 0.39 [0.49] | 0.36 [0.48] | 0.51 [0.50] | 0.41 [0.49] | 0.43 [0.50] |

| Current binge drinker | 0.23 [0.42] | 0.22 [0.41] | 0.35 [0.48] | 0.25 [0.43] | 0.28 [0.45] |

| Current marijuana user | 0.20 [0.40] | 0.19 [0.39] | 0.26 [0.44] | 0.20 [0.40] | 0.20 [0.40] |

| Youth demographic characteristics | |||||

| Female | 0.51 [0.50] | 0.52 [0.50] | 0.46 [0.50] | 0.51 [0.50] | 0.51 [0.50] |

| White | 0.56 [0.50] | 0.56 [0.50] | 0.56 [0.60] | 0.56 [0.50] | 0.58 [0.49] |

| Black | 0.14 [0.35] | 0.14 [0.35] | 0.15 [0.36] | 0.16 [0.37] | 0.08 [0.26] |

| Hispanics | 0.16 [0.37] | 0.16 [0.37] | 0.16 [0.36] | 0.16 [0.37] | 0.18 [0.39] |

| Other races | 0.14 [0.34] | 0.14 [0.34] | 0.13 [0.33] | 0.11 [0.32] | 0.16 [0.37] |

| 9th grade | 0.28 [0.45] | 0.31 [0.46] | 0.01 [0.08] | 0.28 [0.45] | 0.28 [0.45] |

| 10th grade | 0.27 [0.44] | 0.30 [0.46] | 0.01 [0.11] | 0.27 [0.44] | 0.27 [0.44] |

| 11th grade | 0.25 [0.43] | 0.27 [0.44] | 0.10 [0.30] | 0.25 [0.43] | 0.24 [0.43] |

| 12th grade | 0.21 [0.41] | 0.12 [0.33] | 0.88 [0.32] | 0.20 [0.40] | 0.21 [0.41] |

| Merged state-level covariates | |||||

| E-cigarette MLSA Laws | 0.24 [0.43] | 0.27 [0.44] | 0.01 [0.11] | 0.00 [0.00] | 0.00 [0.00] |

| Real cigarette taxes | 2.35 [1.18] | 2.37 [1.19] | 2.21 [1.11] | 2.00 [1.20] | 2.22 [0.72] |

| Comprehensive smoke-free air laws | 0.41 [0.49] | 0.42 [0.49] | 0.34 [0.47] | 0.34 [0.47] | 0.24 [0.43] |

| Bans on e-cigarette use in private work places | 0.01 [0.09] | 0.01 [0.09] | 0.01 [0.10] | 0.00 [0.00] | 0.00 [0.00] |

| Real beer taxes | 0.27 [0.24] | 0.27 [0.24] | 0.29 [0.25] | 0.32 [0.27] | 0.24 [0.13] |

| Zero-tolerance law | 0.41 [0.49] | 0.41 [0.49] | 0.41 [0.49] | 0.22 [0.41] | 0.77 [0.42] |

| Underage drinking: No possession of alcohol | 0.15 [0.36] | 0.16 [0.37] | 0.10 [0.29] | 0.05 [0.23] | 0.10 [0.30] |

| Underage drinking: No consumption of alcohol | 0.08 [0.27] | 0.08 [0.27] | 0.07 [0.25] | 0.11 [0.31] | 0.02 [0.12] |

| Underage drinking: No internal consumption of alcohol | 0.18 [0.38] | 0.18 [0.39] | 0.13 [0.34] | 0.12 [0.32] | 0.00 [0.00] |

| Underage drinking: No purchase of alcohol | 0.21 [0.41] | 0.21 [0.40] | 0.25 [0.43] | 0.31 [0.46] | 0.09 [0.28] |

| Underage drinking: Suspense or revoke driving privileges | 0.36 [0.48] | 0.36 [0.48] | 0.33 [0.47] | 0.35 [0.48] | 0.13 [0.33] |

| Underage drinking: Against underage drinking party | 0.14 [0.34] | 0.13 [0.34] | 0.15 [0.36] | 0.13 [0.34] | 0.11 [0.31] |

| Underage drinking: Keg registration law | 0.21 [0.40] | 0.21 [0.41] | 0.20 [0.40] | 0.21 [0.41] | 0.12 [0.32] |

| Medical Marijuana Laws | 0.26 [0.44] | 0.26 [0.44] | 0.22 [0.41] | 0.09 [0.28] | 0.26 [0.44] |

| Medical Marijuana Laws: home cultivation | 0.12 [0.33] | 0.12 [0.33] | 0.13 [0.33] | 0.07 [0.25] | 0.16 [0.36] |

| Medical Marijuana Laws: legal dispensary | 0.12 [0.33] | 0.12 [0.33] | 0.13 [0.33] | 0.06 [0.25] | 0.10 [0.30] |

| Medical marijuana Laws: non-specific pains | 0.19 [0.40] | 0.20 [0.40] | 0.16 [0.37] | 0.08 [0.27] | 0.17 [0.38] |

| Medical Marijuana Laws: registry | 0.15 [0.36] | 0.15 [0.36] | 0.11 [0.31] | 0.03 [0.18] | 0.11 [0.32] |

| Marijuana decriminalization law | 0.37 [0.48] | 0.38 [0.49] | 0.31 [0.46] | 0.40 [0.49] | 0.10 [0.30] |

| State unemployment rates | 6.66 [2.00] | 6.65 [1.99] | 6.80 [2.06] | 6.82 [2.20] | 6.78 [2.15] |

| Natural logarithm of state per capita personal income | 10.65 [0.18] | 10.66 [0.18] | 10.62 [0.17] | 10.59 [0.15] | 10.53 [0.12] |

Notes: Means and standard deviation (in bracket) are reported. The statistics are weighted by the total underage population at the state by year level retrieved from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program.

Definitions of youth substance use are in the text.

E-cigarette MLSA laws and cigarette excise taxes come from CDC State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation System.

State-level policies on underage drinking come from Alcohol Policy Information System.

State unemployment rates and per capita personal income come from Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Comprehensive smoke-free air laws consist of four venues: government and private workplaces, restaurants, and bars.

Cigarette and beer taxes are inflation-adjusted to 2015 dollars using CPI-U.

5. Empirical Approach

Our baseline model employs the standard difference-in-differences (DD) framework, exploiting variation in the timing of the laws’ implementation within states over time to identify the laws’ effects on youth substance use. Specifically, we estimate the following reduced-form demand function, relating substance use for youth residing in state and surveyed at time directly to the e-cigarette MLSA laws.

| (1) |

where is an indicator for the youth’s past month substance use behavior. For instance, when indicates smoking, denotes the probability that the youth smoked a cigarette in the past month (or is a current smoker). Our key variable of interest, , is an indicator variable for whether state s had an e-cigarette MLSA law in place by the end of February of the survey year and thereafter. The vector contains a full set of youth demographic characteristics and the vector contains the time-varying state policy controls.19 All specifications include state and year fixed effects, denoted by and , to account for the time-invariant state characteristics and the unobserved national trends. We use linear probability models to estimate the laws’ impacts and cluster standard errors at the state level (Bertrand, Duflo, and Mullainathan 2004).20

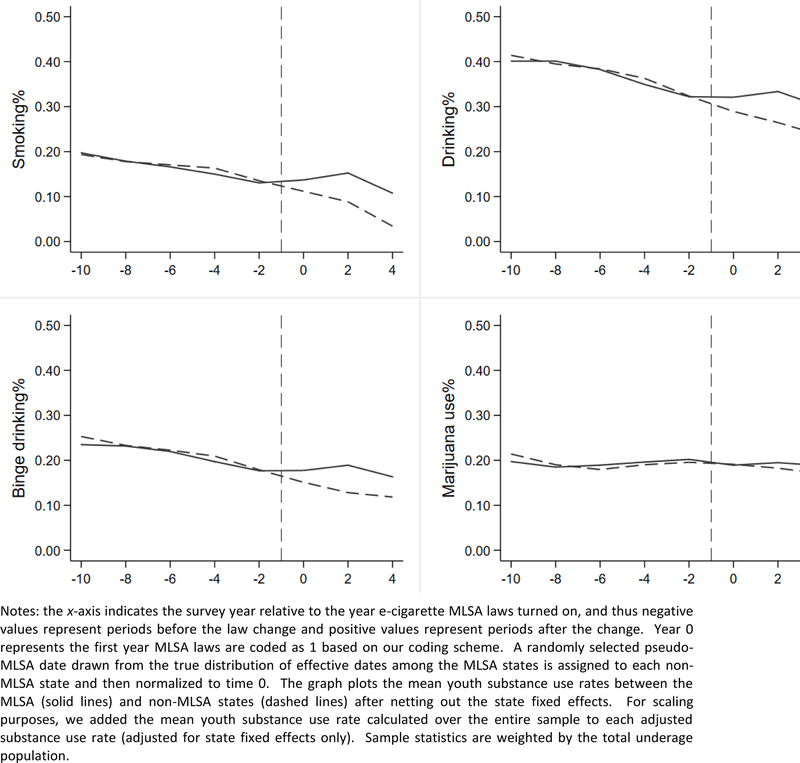

The parameter of interest captures the average reduced-form effects of e-cigarette MLSA laws on youth smoking, drinking, or marijuana use, including through all reinforcing and/or competing pathways as discussed earlier. Identification of policy effects comes from comparing changes in youth substance use rates within states that have implemented the e-cigarette MLSA laws to changes in states that have not yet done so. The DD estimates will yield a causal interpretation if outcome trends for the control states are valid counterfactual to outcome trends for the treated in the absence of the laws (Colman and Dave 2015). We investigate this “common trends” assumption in Figure 1, which is generated using data from the pooled YRBSS and weighted by the total underage population.

Figure 1 –

Youth Substance Use Rates Between E-cigarette MLSA and Non-MLSA States

National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

Figure 1 shows trends for youth smoking, drinking, binge drinking, and marijuana use before and after the implementation of e-cigarette MLSA laws in the context of an event study design. The x-axis of the figure indicates the survey year relative to the year MLSA laws switched on, so that year 0 represents the first year the laws are coded as 1. For states that do not have the laws by February 2015, we assign each a randomly selected pseudo-MLSA date by respecting the true distribution of effective dates among the treated states, and then normalize them to time zero. We use solid lines to track the mean substance use rates for the treated states and dashed lines for the control states. Appendix Table 1 shows that several states have implemented the laws over our study period, and we thus generate Figure 1 by netting out these state-specific characteristics through state fixed effects.21 Figure 1 suggests a few things. Most apparently, the pre-policy trends for all outcomes track each other closely between the treated and control states, providing visual evidence for the “common trends” assumption. We also statistically test for pre-policy differentials by regressing the outcome measure on an indicator for being the treated states interacted with the linear pre-policy trends, controlling for individual- and state- level covariates listed in equation (1). This allows us to assess whether there exist any remaining systematic differences in trends prior to policy exposure between the treated and control states in a specification analogous to the main model. Appendix Table 2 reports the point estimates for the interaction term, which suggest little evidence of differences in pre-policy trends, consistent with Figure 1.

Second, we see clear trend breaks in youth smoking, drinking, and binge drinking around the MLSA restrictions, suggesting positive behavioral responses to the laws, but little or no break in youth marijuana use. Although these diverging trends may suggest positive impacts of the laws on youth smoking and drinking, many confounding factors have yet to be adjusted in this Figure. In the analyses that follow, we take care to account for a multitude of confounders (vector Z), and, in alternate specifications, add state-specific linear time trends (denoted by ) or state-specific pre-policy linear trends to allow for systematically different policy trends across the treated and control states and adjust for the less than perfect nature of the natural experiment.22

We further extend the baseline model in several ways to address some other issues. First, to examine the dynamic impacts of the laws on youth substance use and alternatively assess the “common trends” assumption between the treated and control states after conditioning on covariates, we transform equation (1) into a fully-specified event study design. In particular, we decompose in (1) into a series of policy “leads”, or “placebo” laws, and policy lags, which takes the form:

| (2) |

where all variables except MLSA are defined exactly as in equation (1). For the full event of MLSA, our reference (control) group indicates that the laws will not be switched on in another survey year.23 The parameter captures the contemporaneous policy effect on youth substance use and captures the lagged policy effect one or more survey years after the law’s implementation. Hence, provides evidence of parallel or differential pre-policy trends in outcome variables. If this coefficient is statistically distinguishable from zero, it would suggest that the treatment and control states had differential trends prior to policy adoption, which may undermine the interpretation of the DD effect as causal. Explicitly controlling for the lead effects as in the event study design can also help to partly net out any non-parallel trends.

Next, we assess transitions into/out of smoking once youth are no longer subject to the e-cigarette purchase restriction. Specifically, we estimate the inter-temporal relation associated with how being exposed to an e-cigarette MLSA law when underage affects youth smoking behaviors once they have aged out and are able to purchase e-cigarettes. We do so by restricting the sample to those who are currently 18 or older and thus not subject to the e-cigarette MLSA law, and then estimate the following specification:

| (3) |

Here, is an indicator for whether an e-cigarette MLSA law was effective in youth state at any point in time when he was underage.24 For instance, an e-cigarette MLSA law was effective on January 1st, 2013 in the state of New York. Therefore, a youth aged 18 in 2014 from New York would have been exposed to the law in 2013. Analogously, a youth aged 18 or 19 in 2015 would have also been exposed to the law two years prior. Because age in the YRBSS is top-coded at 18, our strategy might erroneously subsume someone aged 19 or 20 in the treatment group who are in fact not subject to the law in our hypothetical examples. While this may possibly moderate the treatment effects, any attenuation bias is likely to be small.25 We confirm this by dropping the four states where the age limit of legally purchasing e-cigarettes is set at 19 and find that the results are unchanged. The parameter captures how youth exposure to the e-cigarette purchase restrictions, at any point in time when he was underage, affects his substance use behavior once he has aged out of the restriction.

We also build upon the above specifications and assess the margin at which smoking is potentially affected. Specifically, we consider whether, and to what extent, e-cigarette MLSA laws have impacted youth smoking initiation as well as impacts on the other sections of the smoking distribution in addition to the extensive margin focused on above. In alternate specifications, we assess the heterogeneous responses to the laws across gender and grades. We also implement a falsification check, assessing the laws’ effects on youth who should not be affected. Results of these additional tests are in the Online Appendix.

Lastly, we undertake a synthetic control design following Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller (2010) and follow the approach developed by Donald and Lang (2007) and described in Bedard and Kuhn (2015) to derive synthetic DD estimates with multiple treatment assignments and compute standard errors using the Donald and Lang’s two-step estimator. Note that this synthetic DD estimates approach has been employed in several other studies (Choi, Dave, and Sabia 2016, Sabia, Swigert, and Young 2017). Results using this method also appear in the Online Appendix.

6. Results

A. Effects on Smoking

Table 2 presents estimates of the effects of e-cigarette MLSA laws on youth smoking participation among the underage adolescents. Panel A reports baseline effects from the difference-in-differences (DD) model in equation (1). Model 1 suggests a significant 1.1 percentage point (pp) increase in smoking participation among youth exposed to the laws, which translates to about 7 percent increase relative to the baseline means for the control states. We introduce state-specific linear pre-policy trends in Model 2 to net out any systematic, differential trends in smoking across the treated and control states prior to the implementation of the e-cigarette restriction.26 The effect magnitude remains significant and continues to suggest about a 1 pp increase in smoking participation. The policy effect is also robust to controlling for a full set of state-specific linear trends in Model 3, allowing the trends to persist both pre- and post-policy implementation. State-specific time trends capture systematic time-varying state heterogeneity and adjust for the potential endogeneity of the e-cigarette MLSA laws. One possible limitation of adding state-specific time trends is that it reduces the amount of identifying variation (Neumark, Salas, and Wascher 2014). Furthermore, fitting such state-specific linear trends may exacerbate bias, particularly for sample periods and pre-policy windows where trends in smoking (or other substance use) are far from linear. Wolfers (2006) also cautions against adding state-specific linear trends in timing analyses where the policy is modeled as pre-post implementation since such trends may confound both the state-specific time-varying unobservables as well as any dynamic effects of the policy itself. We therefore exercise care in using such method, though it is notable that adding state-specific linear trends does not dilute the estimated effects. If anything, the point estimates are slightly larger. The stability of the estimates bolsters the plausibility of our research design.

Table 2 —

E-cigarette MLSA Law and Youth Smoking

National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

| DV: Youth is a current smoker | DV: Youth is a first-time smoker | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| E-cigarette MLSA Law | 0.011*** | 0.012** | 0.015*** | 0.007** | 0.007* | 0.007** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| Panel B | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≤2 Waves Pre | −0.006 | −0.004 | −0.006 | −0.002 | −0.000 | −0.001 |

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA 1 Wave Pre (Ref.) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| E-cigarette MLSA Wave of Implementation | 0.010*** | 0.015 | 0.018*** | 0.007** | 0.007* | 0.008** |

| (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≥1 Wave Post | 0.020*** | 0.026 | 0.022** | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.009 |

| (0.005) | (0.016) | (0.011) | (0.005) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| Full Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State-specific linear pre-trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| State-specific linear trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Mean of dep. var. in the control states | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Observations | 752,332 | 752,332 | 752,332 | 551,232 | 551,232 | 551,232 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

All models include dummy variables for gender, race, age, and grade levels. State-level covariates listed in Table 1 are included.

In columns 1–3, we define youth as current smokers if any days of smoking over the past month are reported. The analysis sample there is restricted to youth younger than 18.

In columns 4–6, we define youth as first-time smokers if their age at the time of the survey matches the age of first-time smoking.

Youth who never smoke a cigarette are coded zero and youth who initiated smoking prior to the survey are excluded.

Youth younger than 13 or older than 17 are dropped as they cannot be first-time smokers when exposed to an e-cigarette MLSA law.

E-cigarette MLSA law, the leads, and the lags are defined in the text. One wave means one survey year.

Panel B decomposes the timing of the DD effects and presents estimates from a formal event study design as specified in equation (2).27 The results from the event study design underscore three points. First, e-cigarette MLSA laws appear to have a significant “contemporaneous” effect during the full year of implementation, which is about 1.4 pp. Owing to the biennial sampling frame of the YRBSS and data collection typically commencing in March of a given year, the policy indicator is defined such that it switches on if the laws took effect anytime since March of the previous survey year and February of the current year.28 This suggests that the policy could be active for over 12 months, picking up some lag in the policy effect but only for up to 2 years. Second, as the lag increases, there is some suggestive evidence that the response to policy becomes stronger, on the order of 2–3 pp across all models, though estimates in models with the state pre-policy trends are not significant. This possible compounding of the policy effects over time is consistent with an interactive age response. Smoking participation generally increases with age among adolescents; current smoking participation among 16-year-olds is 10.2% compared to 5.0% among 14-year-olds. Hence, an e-cigarette MLSA law in effect when the adolescent was for instance 14 years of age would be expected to have a stronger “bite” as he ages and becomes more likely to contemplate smoking (or use other forms of tobacco) in the future. Third, the lead effects are small in magnitude and insignificant, providing validation to the research design and confirming that the policy is orthogonal to pre-policy trends in smoking.

While our conceptual framework is agnostic about the direction of the effects given the potential for cigarette smoking to either substitute or complement e-cigarette use, the pattern of results that we find – suggesting an increase in smoking participation – is ex post validating when contrasted with the breaking trends in youth smoking around the MLSA restriction. As shown in Figure 1, pre-policy trends suggest a decrease in youth smoking as e-cigarettes entered the market in 2007 and e-cigarette MLSA laws proliferated across states (starting in 2010). Thus, if our models are simply reflecting this decline in smoking as states implemented more e-cigarette MLSA laws, then the DD effects would have suggested (possibly spuriously) a deterrent effect of the laws on youth smoking. However, finding increases in smoking from the policy, despite the declining pre-policy trends, adds confidence that these estimates are not just reflecting the falling smoking rates.

Together, estimates in Table 2 suggest that when faced with the e-cigarette MLSA laws, underage youth are more likely to turn to cigarette smoking. This may prima facie seem counter-intuitive since they are also restricted from purchasing cigarettes; hence, it would appear that underage youth are turning from one restricted substance to another. However, since all youth face purchasing restrictions for cigarettes over the sample period, the implementation of the e-cigarette MLSA laws would increase the relative costs of accessing e-cigarettes (relative to cigarettes), affecting the demand for these substances. Because cigarettes have been in the market for a long time, most youth who smoke may have found alternative ways to bypass the purchase restrictions and obtain their cigarettes through secondary sources, such as “bumming” or borrowing from a friend or adult (Katzman, Markowitz, and McGeary 2007, Hansen, Rees, and Sabia 2013).29 Thus, it is conceivable that these youth are increasing their participation in the secondary cigarette market when purchasing e-cigarettes is prohibited. The secondary market for e-cigarettes, however, may be less well-developed, particularly when recent estimates suggest that only 3.7% of adults vape (Schoenborn and Gindi 2015), thus reducing a source of e-cigarettes for teenagers in secondary markets.30

The smoking participation margin among adolescents in Table 2, columns 1–3 combines first-time smoking, smoking experimentation, regular or heavy smoking, and use of multiple tobacco products. Most smokers initiate smoking in their teenage years, and hence the initiation margin is the most salient for adolescents and also very relevant from a policy stance since it may determine future transitions and paths to nicotine dependence. Models 4–6 in Table 2 specifically look at how exposure to an e-cigarette MLSA law affects smoking initiation. For these analyses, we restrict the sample to youth who have initiated smoking in the given survey year or are non-smokers; thus youth who are current smokers but had initiated smoking habits in the past are excluded.31 These results should be interpreted with care since smoking initiation in the YRBSS is likely coupled with recall errors in the reported age at which smoking was initiated as well as the mismatch between age and survey year.32 These estimates nevertheless suggest that exposure to an e-cigarette MLSA law increases the probability of initiating smoking, on the order of 0.7 pp. The event study design in Panel B also suggest similar magnitudes during the full year of implementation (0.7 pp, capturing significant effects within 12 months of implementation and possibly up to 24 months of implementation, as noted above) and some positive effects thereafter, though these lagged effects are not statistically significant. The magnitudes for smoking initiation represent a little over half of the smoking participation effect identified in models 1–3. Thus, the caveats regarding measurement error notwithstanding, which is likely to bias the initiation effect downward, it appears that some of the positive effects of e-cigarette MLSA laws on smoking participation among underage youth may reflect an increase in smoking initiation and remainder reflects movement across smoking and vaping in former initiates.33

In Table 3, we assess the distributional effects of e-cigarette MLSA laws on youth smoking, but, in the interest of space, we focus on the policy effects on the upper tail of the smoking distribution.34 Following Pesko, Hughes, and Faisal (2016), we define youth as a regular smoker if he smoked cigarettes 20 or more days in the past month and a heavy smoker if he smoked cigarettes every day. Table 3, mirroring Table 2, reports estimates using the specification in (1) (Panel A) and estimates using a fully adjusted event-study design (Panel B). Turning to Panel A, we find that youth exposed to the e-cigarette MLSA restriction are 0.8 pp, or 18 percent relative to the baseline means, more likely to be regular and heavy smokers. In Panel B, we find that the law’s impact continues to be larger in the lagged period than the “contemporaneous” period. While these results are not statistically significant across model specifications, they are economically significant in magnitude. In earlier analyses (Panel A, columns 1–3 of Table 2), we find that e-cigarette MLSA laws increased youth smoking participation by about 7 percent and; in comparison, results here suggest that youth increased regular or heavy cigarettes smoking by 18%, suggesting greater effects along the “intensive” margin when exposed to the e-cigarette MLSA laws.

Table 3 —

E-cigarette MLSA Law and Youth Smoking at Different Margins

National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

| DV: Youth is a regular smoker | DV: Youth is a heavy smoker | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| E-cigarette MLSA Law | 0.007** | 0.010** | 0.008** | 0.008*** | 0.010** | 0.009*** |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| Panel B | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≤2 Waves Pre | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.002 |

| (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA 1 Wave Pre (Ref.) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| E-cigarette MLSA Wave of Implementation | 0.007** | 0.012* | 0.010** | 0.007*** | 0.011** | 0.010*** |

| (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≥1 Wave Post | 0.025*** | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.022*** | 0.010 | 0.016* |

| (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.003) | (0.007) | (0.010) | |

| Full Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State-specific linear pre-trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| State-specific linear trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Mean of dep. var. in the control states | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Observations | 752,332 | 752,332 | 752,332 | 752,332 | 752,332 | 752,332 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

All models include dummy variables for gender, race, age, and grade levels. State-level covariates listed in Table 1 are included.

In columns 1–3, we define youth as regular smokers if they smoked cigarettes at least 20 days over the past month.

In columns 4–6, we define youth as heavy smokers if they smoked cigarettes every day over the past month.

The analysis sample is restricted to youth younger than 18.

E-cigarette MLSA law, the leads, and the lags are defined in the text. One wave means one survey year.

In Table 4, we evaluate if the increase in smoking persists after youth are no longer constrained by the e-cigarette purchasing restriction. Thus, we estimate equation (3) for youth, 18 and above, who have aged out of the laws. Since age in the YRBSS is top-coded as 18 or above and four states (AL, AK, NJ, and UT) set the age for legally purchasing e-cigarettes at 19, our sample may still include a few who are not old enough to buy e-cigarettes. We therefore present models for all states (models 1–3) and after excluding these four states (models 4–6). We discuss here the latter set of models that bypass the potential misclassification, though estimates remain virtually identical whether we include or exclude the states that had set the e-cigarette MLSA at age 19.

Table 4 —

The Intertemporal Relationship Between E-cigarette MLSA Law and Youth Smoking

National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

| DV: Youth is a current smoker | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed to E-cigarette MLSA Law While Underage | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.009 |

| (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.016) | (0.015) | |

| Full Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State-specific linear pre-trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| State-specific linear trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Mean of dep. var. in the control states | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Observations | 93,716 | 93,716 | 93,716 | 93,716 | 93,716 | 93,716 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses.

All models include dummy variables for gender, race, age, and grade levels. State-level covariates listed in Table 1 are included.

The analysis sample is restricted to youth aged 18 or above.

In columns 1–3, we include Alabama, Alaska, New Jersey, and Utah, where the age limits of purchasing e-cigarettes are set at 19.

In columns 4–6, we exclude Alabama, Alaska, New Jersey, and Utah.

The definition of the key regressor, “Exposed to E-cigarette MLSA Law While Underage,” is in the text.

There is little evidence from Table 4 to suggest that exposure to an e-cigarette MLSA law when underage is associated with increased smoking when youth are old enough to purchase e-cigarettes. Hence, we do not find any strong evidence that the increase in smoking persists as youth age out of the e-cigarette MLSA restriction. These models suggest that any effects on underage smoking, among youth exposed to an e-cigarette MLSA law, fade when they aged out of the law and are able to purchase e-cigarettes.35

B. Magnitude of the Smoking Effect

Our estimates thus far suggest that when faced with the e-cigarette MLSA laws, underage youth are more likely to turn to cigarette smoking, at least until they age out of these laws. Results in Table 2 suggest about a 1.3 pp increase in smoking post-policy adoption, which is consistent with findings reported by Friedman (2015) and Pesko et al. (2016).36 To place this magnitude in context, it should be noted that the DD effect we estimate is an intention-to-treat (ITT) effect since our sample includes youth that do not use e-cigarettes. It is unlikely that e-cigarette MLSA laws would have a direct effect on smoking behaviors, independent of their effect on e-cigarette use. If e-cigarette MLSA laws had no effect on e-cigarette use, we should expect no effects on other substance use behaviors as well.

Hence, establishing the first-stage effect of how e-cigarette MLSA laws may have impacted youth e-cigarette use can help frame what the maximal effect should be for spillover responses into smoking (and other substance use) given that these individuals represent the affected group. However, estimating the laws’ effects on e-cigarette use has been a challenge because of data limitation. Youth-based surveys, including the YRBSS and the MTF, have only started asking respondents if they use e-cigarettes in 2014 or 2015. Abouk and Adams (2017), for instance, estimate that the e-cigarette MLSA laws are associated with a significant 10 pp decline in e-cigarette use among high school seniors, based on cross-sectional evidence from the 2014 MTF wave.

The YRBSS started fielding questions on e-cigarette use in the latest 2015 wave. For suggestive evidence, we estimate a similar model to that in (1) for outcomes related to e-cigarette use (ever use and current use) based only on the 2015 YRBSS.37 Table 5 suggests that, among underage youth, e-cigarette MLSA laws reduced current use by about 1 pp (5% decline relative to the baseline mean of 21% vaping participation), and ever use (as a proxy for initiation) by about 4.3 pp (10% decline relative to the baseline mean of 44% ever vaping).38 We previously found evidence that the laws increased youth smoking by about 1.3 pp, and so we calculate a back-of-the-envelope treatment-on-the-treated (TOT) effect of 0.3 using the law’s impact on ever vaping. We use ever vaping for this calculation to better match the longer duration of data available for smoking. In other words, about 3 in every 10 youth may have increased smoking as they reduced e-cigarette use in response to the e-cigarette MLSA restriction. These estimates should be interpreted with considerable caution and are meant to be suggestive due to the inherent difficulties in obtaining the first-stage effect of the laws on e-cigarette use. Nevertheless, they can prove useful in gauging the credibility of the magnitudes on the second-order effects.

Table 5 —

E-cigarette MLSA Law and Youth E-cigarette Use

National and State YRBSS: 2015

| Ever Used E-cigarettes | Current Vapor | |

|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette MLSA Law | −0.043*** | −0.009 |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| Mean of dep. var. in the control states | 0.44 | 0.21 |

| Full controls | Yes | Yes |

| Census Division FEs | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 145,950 | 178,444 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses.

p < 0.01

Both models include dummy variables for gender, race, age, and grade levels.

State-level covariates listed in Table 1 are also included.

Youth aged 18 or above are excluded.

E-cigarette MLSA law is defined in the text.

We define youth as a current vapor if any day of e-cigarette use is reported in the past month.

C. Effects on Drinking and Marijuana Use

Next we examine whether exposure to the e-cigarette MLSA laws has any spillover effects on other substance use among underage youth. In Table 6, baseline DD estimates and dynamic effects from the event study are presented separately for past month drinking and binge drinking, showing little evidence of any consistent effect on alcohol use. Though Figure 1 suggests that the e-cigarette MLSA laws may have increased youth drinking and binge drinking, the estimated policy impacts turn out to be sensitive to model specifications and are never statistically distinguishable from zero. For example, there is some suggestive evidence of a lagged increase in drinking (on the order of about 0.7–1.4 pp, or 2–4% relative to the baseline mean) in the event study specifications (models 2 and 3), but standard errors are large and we cannot reject the null. Table 7 presents estimates of the effect of e-cigarette MLSA laws on past month marijuana use, and here we also find little statistically significant effect. We note that the laws’ effects on substances other than tobacco are third-order effects, and so it is perhaps not surprising that they are quite weak. Hence, while our results suggest that restricting the purchase of e-cigarettes among underage youth may have spilled over into higher smoking, we find little evidence of additional substitution into drinking or marijuana use.

Table 6 —

E-cigarette MLSA Law and Youth Alcohol Use

National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

| DV: Youth is a current drinker | DV: Youth is a current binge drinker | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| E-cigarette MLSA Law | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Panel B | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≤2 Waves Pre | −0.003 | −0.007 | −0.008 | −0.002 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.009) | (0.005) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA 1 Wave Pre (Ref.) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| E-cigarette MLSA Wave of Implementation | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.001 | −0.004 | −0.002 |

| (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.006) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≥1 Wave Post | −0.010 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.009 | −0.014 | −0.009 |

| (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.012) | |

| Full Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State-specific linear pre-trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| State-specific linear trends | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Mean of dep. var. in the control states | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Observations | 711,220 | 711,220 | 711,220 | 711,220 | 711,220 | 711,220 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses.

All models include dummy variables for gender, race, age, and grade levels. State-level covariates listed in Table 1 are included.

In columns 1–3, we define youth as current drinker if any days of drinking over the past month are reported.

In columns 4–6, we define youth as current binge drinker if any days of binge drinking (drank 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row within a couple of hours) over the past month are reported.

The analysis sample is restricted to youth younger than 18.

E-cigarette MLSA Law, the leads, and the lags are defined in the text. One wave means one survey year.

Table 7 —

E-cigarette MLSA Law and Youth Marijuana Use

National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

| Panel A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Youth is a current marijuana user | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| E-cigarette MLSA Law | −0.000 | −0.007 | −0.002 |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Panel B | |||

| DV: Youth is a current marijuana user | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≤2 Waves Pre | −0.010 | −0.006 | −0.012 |

| (0.006) | (0.010) | (0.009) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA 1 Wave Pre (Ref.) | – | – | – |

| E-cigarette MLSA Wave of Implementation | −0.001 | −0.004 | 0.002 |

| (0.006) | (0.012) | (0.010) | |

| E-cigarette MLSA ≥1 Wave Post | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.015 |

| (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.017) | |

| Full Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State-specific linear pre-trends | ✓ | ||

| State-specific linear trends | ✓ | ||

| Mean of dep. var. in the control states | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Observations | 760,063 | 760,063 | 760,063 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses.

All models include dummy variables for gender, race, age, and grade levels. State-level covariates listed in Table 1 are included.

We define youth as current marijuana users if any days of marijuana use over the past month are reported.

The analysis sample is restricted to youth younger than 18.

E-cigarette MLSA Law is defined in the text.

One wave means one survey year.

D. Additional Robustness Checks and Extensions

Of concern that our DD estimates may not be consistent due to the unbalanced nature of the YRBSS, we re-run equation (1) using a strongly balanced sample and report the estimated policy effects on youth cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and marijuana use in Online Appendix Table 1. It is validating that all our estimates are not sensitive across analysis samples and are highly similar in both significance and magnitudes.39

As an additional robustness check, we undertake a synthetic control design following Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller (2010) to adjust the pre-policy trends in youth substance use outcomes between the treated and control states. A detailed explanation of this method (SCM) is outside the scope of the study, but its essence can be viewed as follows: information on youth substance use in a few pre-policy periods coupled with the averages of state-level covariates (Table 1) across the entire pre-policy period are utilized to form a “best” linear combination of control states in which the e-cigarette MLSA laws have not been implemented by the end of our study period (2005–2015). This data-driven method assigns weight to each control state so that any pre-policy differences in outcomes and state-level covariates between the treated and synthetically matched state are minimized, expressly forcing the counterfactuals to have more similar pre-policy trends (Sabia, Swigert, and Young 2017).

For each substance use outcome, we pool together the individually created synthetic samples and retain the synthetic weights. Following the approach developed by Donald and Lang (2007) and described in Bedard and Kuhn (2015), we derive the synthetic DD estimates with multiple treatment assignments and compute standard errors using Donald and Lang’s two-step estimator. Online Figure 1 presents visual evidence for the successful implementation of this method, with all figures showing that the treated and synthetic control states have overlaid trends in the pre-policy periods and clear divergence after the policy implementation.40 Online Appendix Table 2 reports estimates of the policy effects using the pooled sample. Similar to our baseline DD estimates, there is a significant increase in smoking among underage youth and no effects on their use of other substances. The point estimate of a 1 pp increase in youth smoking is similar in magnitude to that from our baseline DD models.

Online Appendix Table 3 carries out a falsification test, examining the impact of e-cigarette MLSA laws on youth smoking within a sample where youth have aged out of the law and were not exposed to the laws while underage. We note that all estimates are statistically indistinguishable from zero and generally small in magnitude relative to the baseline means. Online Appendix Tables 4 and 5 show the policy effects on youth smoking behaviors separately for boys and girls, and for 9th and 10th graders versus 11th and 12th graders. We find that most of the positive e-cigarette MLSA effects on smoking is driven by boys and the effects are similar between these two composite grades.

7. Conclusion:

Economic theory suggests that e-cigarette MLSA laws may reduce e-cigarette use, and we find suggestive evidence of this using a single cross-section of data. Using the MTF data, Abouk and Adams (2017) reached a similar conclusion. We also find strong evidence that e-cigarette MLSA laws increased the probability of youth smoking conventional cigarettes by approximately 1.1 pp (7% relative to the mean smoking rates). In particular, youth who have not smoked in the past but initiated their first cigarettes due to the e-cigarette MLSA restrictions may have contributed to a little over half of the increase in smoking participation. Our estimates of the policy effects on youth smoking are slightly larger than those of Friedman (2015) and Pesko et al. (2016), who both found that the laws increased smoking participation by roughly 0.9 pp. Our slightly larger estimates reflect two additional waves of data in conjunction with some evidence of a stronger lagged policy response. However, our finding that e-cigarette MLSA laws increased cigarette use contrasts from findings by Abouk and Adams (2017) who suggested that the laws decreased smoking among underage seniors (the authors did not report the laws’ effects on other underage populations). Given that both our study and Abouk and Adams use individual-level data, this alone does not appear to account for the differences in results. Our study employs one additional year of data and utilizes data from the pooled YRBSS which yields a sample size approximately 14 times that of the MTF sample employed by Abouk and Adams. Restricting our analyses to the same periods as their study does not alter our results or conclusions. Hence, it is possible that differences between the MTF and the YRBSS sampling schemes and their respective sample sizes may underlie some of the differences in results. While it has been argued that the YRBSS may be more representative at the state level (Carpenter and Cook 2008), and hence may provide more stable estimates of changes in smoking within states over time, further research exploring these differences is warranted.

Our models also suggest that the increase in youth smoking caused by e-cigarette MLSA laws appears to fade once youth age out of the law. Additionally, we do not find any evidence that the laws affect the use of other addictive substances such as alcohol or marijuana use.

While federal regulations require all states to have a cigarette MLSA law of at least 18, some states have made the age limit for purchasing both cigarettes and e-cigarettes higher. As of the 1st quarter of 2018, three states had an MLSA law of 19 and five states (California, D.C., Hawaii, New Jersey, and Oregon) had MLSA laws of 21. Our results suggest some caution in raising MLSA laws for e-cigarettes to 21. It may be preferable to raise cigarette MLSA laws to 21 but maintain e-cigarette MLSA laws at 18 to encourage youth to quit smoking using e-cigarettes. Preventing youth from legally buying e-cigarettes until age 21 may harden preferences for cigarettes and make quitting at younger ages more difficult.

In sum, it is unclear from our results if e-cigarette MLSA laws have a positive impact on public health. It appears that some portion of the decrease in e-cigarette use, about 30% based on crude TOT estimates, may come at the expense of higher conventional cigarette use, at least in the short-term until youth have aged out of the restrictions. If e-cigarettes are only 5% as harmful as traditional cigarettes (Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians 2016), then e-cigarette MLSA laws leading to increased smoking may cause greater harm than benefits. However, such net costs need to be balanced against other considerations such as the potential use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation among older youth and among longer-term smokers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully appreciate comments from Abigail Friedman, Rahi Abouk, and others at the 2017 International Society for Health Economists (iHEA) conference. We also gratefully acknowledge Amanda Shawky for editorial assistance.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA039968 (PI: Dhaval Dave) and R01DA045016 (PI: Michael Pesko)

Appendix Table 1 —. E-Cigarette Minimum Legal Sale Age Laws, 2005 – 2015

| State | Effective Date | State | Effective Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | August 1, 2013 | Montana | January 1, 2016 |

| Alaska | August 22, 2012 | Nebraska | April 9, 2014 |

| Arizona | September 13, 2013 | Nevada | October 1, 2015 |

| Arkansas | August 16, 2013 | New Hampshire | July 31, 2010 |

| California | September 27, 2010 | New Jersey | March 12, 2010 |

| Colorado | March 25, 2011 | New Mexico | June 9, 2015 |

| Connecticut | October 1, 2014 | New York | January 1, 2013 |

| Delaware | June 12, 2014 | North Carolina | August 1, 2013 |

| District of Columbia | October 1, 2015 | North Dakota | August 1, 2015 |

| Florida | July 1, 2014 | Ohio | August 2, 2014 |

| Georgia | July 1, 2014 | Oklahoma | November 1, 2014 |

| Hawaii | June 27, 2013 | Oregon | January 1, 2016 |

| Idaho | July 1, 2012 | Pennsylvania | August 8, 2016 |

| Illinois | January 1, 2014 | Rhode Island | January 1, 2015 |

| Indiana | July 1, 2013 | South Carolina | June 7, 2013 |

| Iowa | July 1, 2014 | South Dakota | July 1, 2014 |

| Kansas | July 1, 2012 | Tennessee | July 1, 2011 |

| Kentucky | April 10, 2014 | Texas | October 1, 2015 |

| Louisiana | May 28, 2014 | Utah | May 11, 2010 |

| Maine | July 4, 2015 | Vermont | July 1, 2013 |

| Maryland | October 1, 2012 | Virginia | July 1, 2014 |

| Massachusetts | September 25, 2015 | Washington | July 28, 2013 |

| Michigan | August 8, 2016 | West Virginia | June 6, 2014 |

| Minnesota | August 1, 2010 | Wisconsin | April 20, 2012 |

| Mississippi | July 1, 2013 | Wyoming | March 13, 2013 |

| Missouri | October 10, 2014 |

Notes: By the end of August 2016, all states except Pennsylvania and Michigan have implemented E-Cigarette MLSA Laws.

Appendix Table 2 –. Test for the Parallel Trends Assumption National and State YRBSS: 2005–2015

| Current Smoker |

Current Drinker |

Current Binge Drinker |

Current Marijuana User |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated ×Pre-trends | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| Full Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year FEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| N | 459,784 | 436,271 | 436,271 | 467,754 |

Notes: Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parenthesis.

Pre-trends refer to the time periods before the implementation of e-cigarette MLSA laws, shown on the x-axis in Figure 1 as negative values.

We convert these negative values to positive by multiplying −1.

Full controls include dummy variables for gender, age, race, and grade levels, as well as all the state-level covariates listed in Table 1.

Youth aged 18 or above are excluded.

Definitions of youth substance use are in the text.

Footnotes

The Tobacco Control Act of 2009 gave the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) jurisdiction over tobacco products, and this “deeming” rule was finalized in 2016.

Among adults, the 2014 National Health Interview Survey shows that 12.6% had ever used e-cigarettes at least once and 3.7% currently use e-cigarettes (Schoenborn and Gindi 2015).

Data from Wave 4 of the Add Health Survey indicated that 34% of youth reported either early use of both alcohol and marijuana, or alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes (Moss, Cen, and Yi 2014).

Utah, New Hampshire, Minnesota, and California enforced the law on May 11, July 31, August 1, and September 27, all in 2010, respectively.

Appendix Table 1 provides a list of states that have implemented the e-cigarette MLSA laws over our sample period spanning 2005–2015.

Data from the 2014 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) suggest that, among youth ages 12–17 who have used tobacco products in the past year, 88% have also consumed alcohol and 56% have used marijuana over this period.

Friedman (2015) is based on 2-year state aggregated data from the NSDUH (spanning 2002–2013) and Pesko et al. (2016) is based on the state-aggregated data from the Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System (YRBSS; spanning 2007–2013).

A recent study by Pesko et al. (2018) shows that higher cigarette prices are positively associated with youth use of e-cigarettes, a result that is consistent with the argument that e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes are economic substitutes.

Eight additional states adopted e-cigarette MLSA laws in 2015.

The predicted decrease in e-cigarette use may be moderated to the extent that retailers do not abide by the law or that youth are able to bypass the law through online vendors.

In most cases, youth aged 18 are old enough to legally purchase e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes except for a few cases where states set the minimum age at 19 or 21.

See, for instance, Crost and Guerrero (2012), Crost and Rees (2013), Dee (1999), Farrelly et al. (2001), Gruber et al. (2003), and Picone et al. (2004).

The national YRBSS is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the state YRBSS, while coordinated by CDC, is usually administered by state health departments or education agencies. State identifiers are not provided in the national YRBSS by default, but we obtained these from CDC and use them in all analyses. We received the state-level data from either CDC directly or from the states. Some states do not distribute their data due to low response rates, and so we did not use them in the analysis.

See, for instance, Carpenter and Cook (2008), Anderson et al. (2015), Sabia and Anderson (2016), and Hansen, Sabia, and Rees (2017).

As the first set of states implemented e-cigarette MLSA laws in 2010, this ensures that our sample period includes a five-year pre-policy window at a minimum. We do not extend our sample to previous years in order to minimize introducing confounding trends and trend breaks from periods prior to when e-cigarettes became available in the U.S. However, we note that our estimates are robust to utilizing all waves of the YRBSS (1991–2015) or to starting the analyses in 2007, the year when e-cigarettes entered the U.S. Results for these alternate sample periods are available from the authors upon request.

Following this logic, we code four states as having e-cigarette MLSA laws by 2011, nine additional states by 2013, and 21 states in total (beyond the 13 previously) by 2015.

Results from regressions without weights are very similar and are available from the authors upon request.

Four states (Alabama, Alaska, New Jersey, and Utah) set the purchasing age of e-cigarettes at 19 years old, but age in the YRBSS is top-coded at “18 or above” and we are unable to single out youth who are 19 years of age. This will result in some individuals “18 and above” being subject to the e-cigarette MLSA laws, that is, some youth in the control group may be treated. We found that moving these youth into column 2 does not at all change the means. Based on the 2016 American Community Survey, among current high-school enrollees nationally between the ages of 12–19, only about 2% are 19, and only 4.3% (based on the share of the population of the affected states, AK, AL, NJ and UT) of these 19-year olds would be misclassified as being not treated. Hence, any attenuation bias from this misclassification is negligible. We show later that our results are not sensitive to excluding these four states from the analyses.

Inflation-adjusted cigarette and beer taxes expressed in 2015 dollars, a set of indicator variables for MMLs, restrictions on vaping in private workplaces and smoking in public places, a set of indicator variables for underage drinking regulations, state unemployment rates, and the natural logarithm transformed state per capita income.

Our results and conclusions are not materially affected if the specification is estimated via a logit or probit regression.

For scaling purposes, we added back the mean youth substance use rates across the entire sample to each adjusted substance use rate (adjusted for state fixed effects). We also hold y-axis fixed for ease of comparison.

State-specific pre-trends are created by subtracting survey year from the year MLSA switched on. We use only the negative values and set all the positive values to zero. We then convert all the negative values to positive by multiplying −1.

We use survey year instead of the calendar year to define event time in order to respect the biennial structure of the YRBSS data. Our results are robust to using the calendar year in defining event time.

For states where no e-cigarette MLSA laws were enacted during the study period, this variable equals zero.

Among current high-school enrollees nationwide between the ages of 12–21, only about 2% are 19, and less than 1% are 20 or 21 (based on the 2015 American Community Survey). Thus, at most 3% of the sample who may be untreated may be erroneously classified as being treated, and this would lead the treatment effect to be understated by at most a factor of 3% (for instance, an estimated treatment effect of 2.9 percentage points when the true treatment effect is 3 percentage points). This attenuation factor assumes that all 19-year olds are untreated, when most of them would have been treated if they lived in a state that had enacted an e-cigarette MLSA law in the past; hence in practice the attenuation bias is likely to be even smaller.

State-specific pre-trends allow only the pre-policy trends to differ and therefore attribute any potential break in trends at to the policy.

In keeping with the biennial sampling scheme of the YRBSS, these models control for indicators for the full year of policy implementation, one or more survey years post-policy implementation, one survey year before implementation (reference category) and two or more survey years before implementation.

For instance, for respondents interviewed in the 2013 YRBSS wave, the implementation indicator would equal 1 in 2013 if the state they lived in adopted the policy anytime between March 2011 and February 2013.

A dollar increase in cigarette taxes is estimated to decrease the probability of youth getting cigarettes through a secondary market by 5 or 6 percent, but cigarette taxes had little impact on youth obtaining cigarettes through borrowing or taking from a store or family member. This may suggest that they have alternative means to bypass the rising costs of cigarettes.

See https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db217.htm. Furthermore, while it may be relatively easier for a youth to borrow or “bum” a combustible cigarette from a friend or adult, which by definition is disposed after use, the long-lasting properties of e-cigarettes (e.g. even one disposable e-cigarette can last up to 400 puffs or equivalent to one pack of cigarettes) makes it more difficult to borrow or bum from another user.

We define youth as a first-time smoker if his age at the time of survey matches the reported age when he first tried smoking cigarettes.

For instance, a 15-year-old surveyed in 2013 who reported that they initiated smoking at age 15 would be coded as having initiated smoking in 2013. However, the youth may have initiated smoking in 2012 while still 15 years of age.

It should be noted that adolescents aged 14–17 who are current smokers are likely to have initiated very recently; hence, any change in the smoking margin for this age group may still reflect initiation, experimentation, and trying out different substances.

Results for MLSA treatment effects on the remaining part of the distribution are very similar to what is reported in Table 3 below and are available from the authors upon request.

Most smokers initiate smoking during adolescence, with 16 years of age being the mode among ever-smokers (based on data from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health). Hence, accumulation of the addictive smoking stock is still relatively low.

Both studies find about a 1 pp increase in smoking among underage youth, based on data up to 2013. Our slightly larger estimate (up to 1.5 pp in some model specifications) reflect two additional years of data (YRBSS spanning up to 2015) in conjunction with some evidence that the lagged policy response are slightly larger over time.

Given the single wave of data, we are not able to control for state fixed effects, and year fixed effects are not necessary. Instead, we include census division fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity at this geographic level. Models are saturated with all other state-level policy controls.

Similar to Abouk and Adams, the effects (not shown) are somewhat larger for older adolescents (11th and 12th graders).

We also run equation (1) using only the state YRBSS that are representative of the sampled states. The estimated MLSA effects are consistent in magnitude with findings from the full sample; however, due to lower sample size, statistical power is somewhat attenuated.

The resulting trends for youth cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and marijuana use in each MLSA state and its synthetically matched states are available from the authors.

Contributor Information

Dhaval Dave, Bentley University, NBER & IZA, Department of Economics, 175 Forest St., AAC 195, Waltham, MA 02452, ddave@bentley.edu.

Bo Feng, IMPAQ International, 10420 Little Patuxent Parkway, Suite 300, Columbia, MD 21044.

Michael F. Pesko, Georgia State University, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Department of Economics, 14 Marietta Street, NW, 5th Floor, Atlanta, GA 30303, mpesko@gsu.edu

References:

- Abadie A, Diamond A, and Hainmueller J. 2010. “Synthetic Control Methods for Comparative Case Studies: Estimating the Effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 105 (490):493–505. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abouk Rahi, and Adams Scott. 2017. “Bans on electronic cigarette sales to minors and smoking among high school students.” Journal of Health Economics doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams David B. 2014. “Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete?” Jama 311 (2):135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Sajjad, and Billimek John. 2007. “Limiting youth access to tobacco: Comparing the long-term health impacts of increasing cigarette excise taxes and raising the legal smoking age to 21 in the United States.” Health Policy 80 (3):378–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D Mark, Benjamin Hansen, and Daniel I Rees. 2015. “Medical marijuana laws and teen marijuana use.” American Law and Economics Review:ahv002

- Bedard Kelly, and Kuhn Peter. 2015. “Micro-marketing healthier choices: Effects of personalized ordering suggestions on restaurant purchases.” Journal of health economics 39:106–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand M, Duflo E, and Mullainathan S. 2004. “How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (1):249–275. doi: 10.1162/003355304772839588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon Thomas H, Goniewicz Maciej L, Hanna Nasser H, Hatsukami Dorothy K, Herbst Roy S, Hobin Jennifer A, Ostroff Jamie S, Shields Peter G, Toll Benjamin A, and Tyne Courtney A. 2015. “Electronic nicotine delivery systems: a policy statement from the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology.” Clinical Cancer Research 21 (3):514–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter Christopher, and Cook Philip J. 2008. “Cigarette taxes and youth smoking: new evidence from national, state, and local Youth Risk Behavior Surveys.” Journal of Health Economics 27 (2):287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. “YRBSS Fact Sheets and Comparison of State/District and National Results” accessed Jan,29. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/results.htm.

- Chaloupka Frank J, and Michael Grossman. 1996. Price, tobacco control policies and youth smoking. National Bureau of Economic Research

- Chaloupka Frank J, and Pacula Rosalie Liccardo. 1998. An examination of gender and race differences in youth smoking responsiveness to price and tobacco control policies. National Bureau of Economic Research

- Choi Anna, Dave Dhaval, and Sabia Joseph J. 2016. Smoke gets in your eyes: Medical marijuana laws and tobacco use. National Bureau of Economic Research

- Colman Gregory, and Dave Dhaval. 2015. It’s About Time: Effects of the Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Mandate On Time Use. National Bureau of Economic Research

- Crost Benjamin, and Guerrero Santiago. 2012. “The effect of alcohol availability on marijuana use: Evidence from the minimum legal drinking age.” Journal of Health Economics 31 (1):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crost Benjamin, and Rees Daniel. 2013. “The minimum legal drinking age and marijuana use: New estimates from the NLSY97.” Journal of health economics 32 (2):474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]