Abstract

Background:

Breastfeeding provides beneficial health outcomes for infants and their mothers, and increasing its practice is a national priority in many countries. Despite increasing support to exclusively breastfeed, the prevalence at 6 months remains low. Breastfeeding behavior is influenced by a myriad of determinants, including breastfeeding attitudes, knowledge, and social support. Effective measurement of these determinants is critical to provide optimal support for women throughout the breastfeeding period. However, there are a multitude of available instruments measuring these constructs, which makes identification of an appropriate instrument challenging.

Research aim:

Our aim was to identify and critically examine the existing instruments measuring breastfeeding attitudes, knowledge, and social support.

Methods:

A total of 16 instruments was identified. Each instrument’s purpose, theoretical underpinnings, and validity were analyzed.

Results:

An overview, validation and adaptation for use in other settings was assessed for each instrument. Depth of reporting and validation testing differed greatly between instruments.

Conclusion:

Content, construct, and predictive validity were present for most but not all scales. When selecting and adapting instruments, attention should be paid to domains within the scale, number of items, and adaptation.

Keywords: attitudes, breastfeeding, human milk, instruments, knowledge, psychometric analysis, review, social support

Background

Breastfeeding provides optimal health for infants in the first 6 months of life and provides valuable health benefits for the mother (UNICEF, 2015). The World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first 6 months for maximum health benefits and continued breastfeeding with appropriate complementary foods for 2 or more years (UNICEF, 2015; World Health Organization, 2015).

However, despite increased EBF support from organizations like the World Health Organization, EBF rates at 6 months remain low (37% globally) and global suboptimal breastfeeding practices contribute to 11.6% of mortality for children younger than 5 years (Victora et al., 2016). A better understanding of breastfeeding determinants and barriers to its practice is needed to improve global breastfeeding levels.

Breastfeeding practices can be understood as being determined by a constellation of factors that span the ecological framework from the individual-level characteristics to family (or microsystem) to the political systems (or macrosystem) that influence breastfeeding practice (Bronfenbrenner, 2009; Tuthill, McGrath, Graber, Cusson, & Young, 2016). Breastfeeding attitudes and knowledge and breastfeeding social support represent the microsystem and macrosystem levels of the ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 2009) and are important predictors of breastfeeding behavior. Each construct can affect breastfeeding practice independently, or through influencing one other.

Breastfeeding attitudes and knowledge (i.e., feelings, moods, or emotions and the facts, truths, or principles toward breastfeeding, respectively) (De Jager, Skouteris, Broadbent, Amir, & Mellor, 2013) operate mainly at the microsystem level. It has been shown that attitudes and knowledge toward breastfeeding are strongly predictive of EBF duration (Chezem, Friesen, & Boettcher, 2003; De Jager et al., 2013). Although breastfeeding attitudes and knowledge are referred to jointly, it is important to note that they are two closely related, albeit separate, constructs that are commonly assessed together. Whereas breastfeeding attitudes are an affective (i.e., a characteristic or trait related to feelings or emotions; McCoach, Gable, & Madura, 2013) determinant, breastfeeding knowledge is factual. Breastfeeding social support is a third breastfeeding construct that may affect breastfeeding practice (Chezem et al., 2003) and operates at the microsystem and macrosystem levels (e.g., support toward a mother directly and support that is established through political systems). Greater breastfeeding social support is linked to EBF initiation and duration (Chezem et al., 2003; De Jager et al., 2013). Together, breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, and social support represent a substantial portion of a mother’s orientation toward breastfeeding and warrant an inclusive examination. Consequently, the ability to assess breastfeeding attitudes, knowledge, and social support could help identify those at risk for suboptimal breastfeeding practices.

There are a number of scales to measure each of these separate, but related, constructs. However, the selection of an appropriate scale from among these possibilities is daunting, given that there has been no descriptive examination or critical comparison of the instruments. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide a descriptive overview of existing instruments measuring breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, and social support, including the theoretical frameworks on which they were built, their validation (if any), and their application beyond the original settings. It is our intention that this review will facilitate the improved assessment of these important determinants of breastfeeding by both researchers and practitioners. By facilitating more rigorous and harmonized measurements, we hope to help pinpoint instruments that result in meaningful and relevant data that enhance our knowledge of breastfeeding determinants.

Methods

A literature search was conducted between February and March 2014 and updated October 2015 to identify instrument development articles on mother’s (1) breastfeeding attitudes and/or knowledge or (2) breastfeeding social support. The electronic databases PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and Health and Psychosocial Instruments were searched using the keywords breastfeeding, human milk, infant feeding, instrument, questionnaire, instrument, and tool. The MeSH term “breast feeding” was used for PubMed. Additional search terms to identify breastfeeding attitudes and knowledge instruments included development, attitude, belief, knowledge, and information. Additional search terms to identify breastfeeding social support instruments included social, family, and systems support. The references of related articles and the gray literature were also searched to identify eligible papers.

Inclusion criteria included being (1) an original instrument development article focused on women’s breastfeeding attitudes, knowledge, or social support and (2) written in English. There were no limits placed on publication date. Because two people oversaw the critique process, any uncertainties about the suitability of the inclusion of the instrument were discussed as a group until resolution.

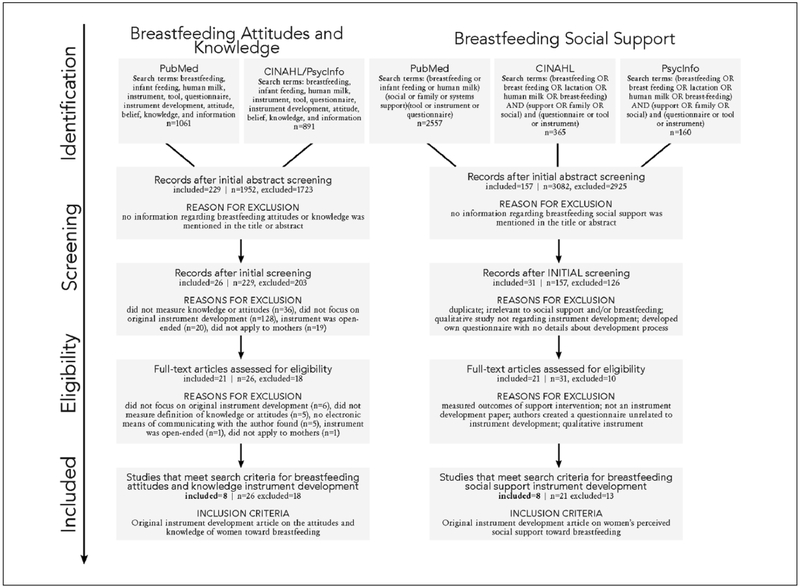

For attitudes and knowledge, 1,952 attitudes and knowledge articles were identified by CSC (see Figure 1). After abstract screening, 229 articles were included and 1,723 were excluded due to failure to mention an instrument meeting inclusion criteria. In a second round of screening that included a review of articles, 203 articles were excluded for reasons such as not matching the definition of knowledge or attitudes, not focusing on original instrument development, not focusing on women as the target demographic, or consisting entirely of closed-ended items to facilitate objective scoring.

Figure 1.

Inclusion process.

Twenty-six articles were fully reviewed. Of these, 5 did not match the definition of knowledge or attitudes (i.e., Caswell, 2008; Kelley, Kviz, Richman, Kim, & Short, 1993; Lakshman et al., 2011; Leff, Jefferis, & Gagne, 1994; Mulder & Johnson, 2010), 6 did not focus on original instrument development (i.e., Anchondo et al., 2012; Dick et al., 2002; Fantasia, Sutherland, & Fontenot, 2012; Fonseca-Machado, Haas, Stefanello, Nakano, & Gomes-Sponholz, 2012; Radaelli, Riva, Verduci, Agosti, & Giovannini, 2012), 1 consisted of open-ended items (i.e., Cusson, 1985), 1 was directed exclusively toward a non-mother demographic (i.e., Ekström, Matthiesen, Widström, & Nissen, 2005), and 5 more were excluded because no electronic means of communicating with the author could be found (i.e., Dávila Torres, Parilla, & Gorrín Peralta, 2000; Giles et al., 2007; Grossman, Harter, & Hasbrouck, 1991; Siddell, Marinelli, Froman, & Burke, 2003; Verma, Saini, & Singh, 1993).

For breastfeeding social support, a total of 3,082 articles was initially identified by AL (see Figure 1). An initial abstract screening excluded 2,925 articles because no information regarding breastfeeding social support was mentioned. After reviewing the remaining manuscripts, an additional 126 articles were excluded for reasons such as (1) breastfeeding social support was not measured, (2) the manuscript purpose was to conduct a qualitative study and not instrument development, and (3) instrument development procedures were not described. With the remaining manuscripts, a full-text evaluation was completed. Eleven articles were excluded, leaving 8 articles that met the inclusion criteria for an original instrument development article on women’s perceived social support toward breastfeeding.

A total of 16 instruments met inclusion criteria. Their authors were contacted to obtain the original breastfeeding instruments (cf. online supplementary material for those that were made available). For each of these 16 instruments, the stated purpose, underlying theoretical frameworks, and number of times each instrument has been used in its original or an adapted version are reviewed. Theoretical frameworks and definitions allow instrument developers to apply conceptual definitions to their research of interest (Grant & Osanloo, 2014). As such, the application of a theoretical framework in instrument development is essential for understanding the item meaning and to ensure that the instrument reflects study intention (McCoach et al., 2013).

Validity is the extent to which the interpretation of test scores supports the proposed uses of the instruments (McCoach et al., 2013). In this review, we report on three levels of validity testing considered standard reporting in instrument development procedures (McCoach et al., 2013), which include content, construct, and predictive. There are multiple options to testing each type of validity. The standard definition and approach to validating each construct is as follows.

Content validity includes the conceptual definition and the operational definition or how the construct is measured in practice (McCoach et al., 2013). The construct’s definition must capture aspects of the construct investigated, and the operational definition must comprehensively and accurately capture the conceptual definition (McCoach et al., 2013). The intended domains of an instrument signify areas of breastfeeding that the authors deem important but also indicate which segments of their respective theoretical frameworks were addressed. Content experts review each item for its relevance to, its fit with, and understandability of the intended concept to ensure strong content validity. To obtain more objective findings, a content validity index scale may be applied, which requires content experts to rate each item on a number of criteria (e.g., fit, relevance, understandability), which the developer then uses to revise items if needed (see Lynn, 1986, as a reference).

Construct validity aims to measure how well relationships among items reflect their intended domain. This is typically assessed using factor analyses (McCoach et al., 2013). Depending on the instrument development process, there are several types of factor analyses that may be performed (e.g., confirmatory or exploratory) and statistical functions used (e.g., types of rotations).

To forecast future behaviors or characteristics based on a criterion variable, predictive validity is used to illustrate how effective an instrument is at determining future behavior. Successful predictions allow instrument administrators to forecast future characteristics based on instrument results (McCoach et al., 2013). In this review, we describe the validity and reliability testing that was reported by instrument developers.

In sum, the standard way to report validity is through three separate validity tests: (1) content validity testing with content experts, (2) construct validity by way of a factor analysis, and (3) predictive validity that is performed using different statistical tests, looking at how the instrument can predict a specific outcome in the future. In addition to validity testing, reliability of the data is reported using Cronbach’s alpha.

Reliability, defined as the extent to which data results produce similar findings on repeated trials, is similar to but different from construct validity. Reliability refers to the consistency of test scores, whereas validity refers to the accuracy of inferences made from intended concepts being measured. A Cronbach’s alpha serves as a statistical metric of how reliable the data generated from the instrument are (McCoach et al., 2013). Generally, a Cronbach’s alpha of > 0.70 is considered to be the minimum threshold for research purposes (Peterson, 1994).

In this review, validity testing is reported per the original instrument developer’s description. Although most adhered to standard reporting criteria, if instrument developers reported validity or reliability testing in other formats or provided only partial results, their processes were described according to the original manuscript text. Testing an instrument among the target population to ensure that it is valid and yields data that are reliable increases confidence in research results and may assist researchers and health care providers in choosing an appropriate breastfeeding attitudes and knowledge or breastfeeding social support instrument.

Results

Each instrument is critically assessed by way of an overview (see Tables 1 and 2), discussion of validation (see Tables 3 and 4), and summary of instrument use beyond original instrument development (see Tables 5 and 6). If present, domains (referred to as factors by some instrument developers) of each instrument are also described (see Tables 3 and 4). Of note, the consistency with which construct validity is reported varies greatly between instruments; therefore, we describe the results to match the detail and specificity of that included within the original text (for additional information, see Tables 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Overview of Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Instruments.

| Tool (Citation) | Site | Purpose | No. of Items | Score Rangea |

Meaning of Score | Theoretical Framework |

Instrument Availability |

| Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire (Brodribb, Fallon, Jackson, & Hegney, 2008) | Australia | To describe the relationship between length of personal breastfeeding experience and breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes | 90 Items, 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) | Not discussed | Higher score indicates more positive attitudes and higher knowledge | Not discussed | Dr. Brodribb: brodribb@usq.edu.au; instrument unavailable |

| Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (de la Mora, Russell, Dungy, Losch, & Dusdieker, 1999) | United States | “To develop a simple, easily administered instrument that will measure maternal attitudes toward infant feeding” | 17 Items, 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) | Not discussed | Higher score indicates more positive attitude toward breastfeeding | Not discussed | Dr. Russell: drussell@iastate.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Preterm Infant Feeding Survey (Dowling, Madigan, Anthony, Elfettoh, & Graham, 2009) | United States | “Examine attitudes concerning feeding decisions of mothers of preterm infants” | 78 Items | Not discussed | Higher score indicates stronger or more positive beliefs and attitudes | Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) | Dr. Dowling: dad10@case.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Breast Milk Expression Experience (Flaherman et al., 2013) | United States | “Develop a measure to evaluate women’s experiences of expressing milk” | 11 Items, 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) | Not discussed | Higher score indicates better experiences | Not discussed | Dr. Flaherman: flahermanv@peds.ucsf.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool (Janke, 1992) | United States | To identify women at risk for premature weaning based on breastfeeding attitudes | 94, 6-Point summated rating scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree), 1 (very influential) to 6 (not at all influential), 1 (very important to me) to 6 (not important to me), 1 (definitely breastfeed) to 6 (definitely not breastfeed), and 1 (do not care at all) to 6 (care very much) | Not discussed | Not discussed | Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) | Dr. Janke: afjrj@uaa.alaska.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Breastfeeding Knowledge, Attitude, and Confidence Scale (Laanterä, Pietilä, & Pölkki, 2010) | Finland | “To describe breastfeeding knowledge of childbearing parents as well as to discover the demographic variables related to it” | 87 Items, 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) | 22 Point maximum on knowledge scale; others not discussed | Higher score indicates greater knowledge | Not discussed | Dr. Laanterä: laantera@hytti.uku.fi; instrument unavailable |

| Breast-feeding Attitude Scale (Lewallen et al., 2006) | United States | To serve the same purpose as the Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool in identifying women at risk for premature weaning based on breastfeeding attitudes while making the instrument easier to administer and score | 20 Items, yes/no questions | 20 to 40 | Higher score indicates more positive attitudes toward breastfeeding | Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) | Dr. Lewallen: lplewall@uncg.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Breastfeeding Behavior Questionnaire (Libbus, 1992) | United States | To examine attitudes and beliefs that are thought to affect feeding choice and breastfeeding behavior among diverse social and cultural groups | 12 Items, 6-point Likert-type scale, anchors not discussed | 12 to 72 | Lower score indicates more positive attitudes and more accurate knowledge concerning breastfeeding | Not discussed | Dr. Libbus: libbusm@missouri.edu; instrument unavailable |

Score range was calculated and not explicitly stated.

Table 2.

Overview of Breastfeeding Social Support Assessment Tools.

| Tool (Citation) | Site | Purpose | No. of Items | Score Range | Meaning of Score | Theoretical Framework |

Instrument Availability |

| Workplace Breastfeeding Support Scale (Bai, Peng, & Fly, 2008) | United States | “To develop and explore psychometric properties of such an instrument … to assess a mother’s perception of the support for breastfeeding at the workplace” | 12 Items, 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) | 12 to 84a | Higher score indicates more positive perception of breastfeeding support | Not discussed | Dr. Bai: baiy@mail.montclair.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Utilization of Support Network Questionnaire (Buckner & Matsubara, 1993) | United States | “To determine how the breastfeeding mother utilizes her support network for successful breastfeeding” | 10 Items, 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not helpful) to 5 (very helpful), two open-ended questions | 10 to 50a (1 to 5 for 10 closed-ended questions) | Higher score indicates more support | Not discussed | Dr. Buckner: ebuckner@southalabama.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Modified Breastfeeding Attrition Prediction Tool (modified BAPT) (Evans, Dick, Lewallen, & Jeffrey, 2004) | United States | “Examined the effectiveness of a modified BAPT … in predicting cessation of breastfeeding prior to 8 weeks” | Social and professional support scale: 10 categories, 5-point Likert-type scale from breastfeed to formula feed and important to not important | 10 to 250 | Higher score indicates greater support | Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) | Dr. Evans: mevans26@uwo.ca; instrument unavailable |

| Supportive Needs of Adolescents Breastfeeding Scale (Grassley, Spencer, & Bryson, 2013) | United States | “To measure adolescents’ perceptions of the nurse support they received when initiating breastfeeding” | 18 Items, 6-point Likert-type scale, anchors not discussed | Not discussed | Higher score indicates higher perceptions of support from nurses among adolescents | Theory of Social Support (House, 1981) | Dr. Grassley: janegrassley@boisestate.edu; instrument unavailable |

| Breastfeeding and Employment Study: Employee Survey (Greene & Olson, 2008; Greene, Wolfe, & Olson, 2008) | United States | “To create a new instrument designed to measure perceptions of workplace breastfeeding support from the viewpoints of new mothers” | 41 Items, 4 yes/no questions, 37 4-point Likert-type scale questions from strongly agree to strongly disagree | Not discussed | Not mentioned | Social ecological framework (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008) | Dr. Beth Olson: olsonbe@msu.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Perceived Breastfeeding Support Assessment Tool (Hirani, Karmaliani, Christie, Parpio, & Rafique, 2013) | Pakistan | “To address the low rate of BF prevalence among working mothers in the Pakistani urban setting through the development and testing … of a tool” | 29 Items, anchors vary (see instrument) | Not discussed | Not discussed | Socio-ecological model/ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2009) | Dr. Hirani: shela.irani@aku.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

| Hughes Breastfeeding Support Scale (Hughes, 1984) | United States | “To develop an instrument that would measure types of support received by a breastfeeding mother” | 30 Items, 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 (no help at all) to 4 (as much help as 1 wanted) | 10 to 40a (1 to 4 for 10 items per subscale); three subscales scored separately | Higher score indicates more social support | Theory of Social Support (Cobb, 1979; House, 1981) | Not discussed; instrument available as online supplement |

| Matich and Sims Scale (Matich & Sims, 1992) | United States | “To elucidate the sources, types and amounts of social support perceived by women during their 3rd trimester of pregnancy and after 3-4 weeks of postpartum breastfeeding” | 23 Items, 6-point Likert-type scale from 1 (interferes, prevents, or hinders) to 6 (extremely helpful) | 23 to 138a (1 to 5 for 23 questions) | Higher score indicates more support | Not discussed | Dr. Matich: jrm34@msstate.edu; instrument available as online supplement |

Score range was calculated and not explicitly stated.

Table 3.

Validation Studies of Breastfeeding Attitudes and Knowledge Assessment Tools.

| Tool (Citation) | Place of Validation | Population Tested | Content Validity | Construct Validity |

Predictive Validity | Reliability | Domains/Factors Identified |

| Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire (Brodribb, Fallon, Jackson, & Hegney, 2008) | Australia (all states except Tasmania) | 161 Australian GP registrars in their final year of training | Three doctors and a researcher with a background in breastfeeding education | Not discussed | Not discussed | Cronbach’s alpha for knowledge scale = 0.83, item-total correlation < 0.2; Cronbach’s alpha for attitude scale = 0.84, item-total correlation < 0.2 | Not discussed |

| Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (de la Mora, Russell, Dungy, Losch, & Dusdieker, 1999) | Community hospital in medium-size midwestern city, United States | (1) 125 Postpartum women; (2) 130 postpartum women; (3) 725 postpartum women who had initiated breastfeeding while in the hospital | (1) Not discussed; (2) not discussed; (3) not discussed | (1) Not discussed; (2) not discussed; (3) not discussed | (1) “Attitude toward infant feeding was found to be a significant predictor of choice of feeding method”; (2) “Attitude toward breastfeeding was found to be a significant predictor of choice of feeding method”; (3) “Mothers with more positive attitudes were found to engage in both exclusive and partial breast-feeding for a longer period of time” | (1) Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86, item-total correlation 0.22 < × < 0.68; (2) Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85, item-total correlation 0.23 < × < 0.69; (3) Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68, item-total correlation 0.07 < × < 0.45 | Not discussed |

| Preterm Infant Feeding Survey (Dowling, Madigan, Anthony, Elfettoh, & Graham, 2009) | Urban level 4 neonatal intensive care unit and transitional nursery in the United States | 105 Postpartum mothers of preterm infants | 5 Doctorally prepared nurses with experience with lactation issues of mothers of hospitalized preterm infants | Exploratory factor analysis using principal axis factoring with oblimin rotation, eigenvalues > 1, and examination of scree plots of eigenvalues | “Negative breastfeeding sentiment and lower subjective norm and breastfeeding control scores were significantly associated with premature weaning at 8 weeks” | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80 | (1) Negative breastfeeding sentiment, (2) positive breastfeeding sentiment, (3) subjective norms, (4) breastfeeding control |

| Breast Milk Expression Experience (Flaherman etal., 2013) | University of California San Francisco Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente South Sacramento, and Stanford University Medical Center in California, United States | Administered “immediately after expression to 68 mothers who expressed milk post-partum” | Four content experts | Study did not have statistical power to report on construct validity | Higher scores were associated with greater likelihood of breast milk expression at 1 month | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.703 | Not discussed |

| Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool (Janke, 1992) | Hospital in United States | 248 Mothers daily for 4 months postpartum | Assessed by a panel of 10 lactation experts | Exploratory factor analysis with principal components procedure for factor extraction and orthogonal (Varimax) rotation | Analyzed difference in mean regression factor scores between women who were exclusively breastfeeding and exclusively formula feeding at 6 or 16 weeks; 5 out of 6 factors were predictive | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80 | (1) Negative breastfeeding sentiment, (2) negative formula-feeding sentiment, (3) positive breastfeeding sentiment, (4) breastfeeding control, (5) professional support, (6) support of family and friends |

| Breastfeeding Knowledge, Attitude, and Confidence Scale (Laanterä, Pietilä, & Pölkki, 2010) | 8 Maternity health care clinics in Finland | 123 Pregnant mothers and 49 fathers | Five breastfeeding experts and health care officials acquainted with breastfeeding counseling | Not discussed | Not discussed | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84, item-total correlations 0.215 < × < 0.604 with 70% >0.30 | Not discussed |

| Breast-Feeding Attitude Scale (Lewallen et al., 2006) | Specialty women’s hospital and community hospital in central North Carolina, United States | 108 Postpartum mothers | Not discussed | Not discussed | Differentiated between mothers who initially chose to breastfeed or formula feed; did not differentiate between women who would continue to breastfeed and those who would wean prior to 8 weeks postpartum | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85 | Not discussed |

| Breastfeeding Behavior Questionnaire (Libbus, 1992) | United States | 9 Members of a La Leche League group and 8 members of a group of prenatal clients of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; all were previous or current breastfeeders and pregnant | A panel of local authorities in nutrition and nursing | Not discussed | Not discussed | Not discussed | Not discussed |

Table 4.

Validation Studies of Breastfeeding Social Support Assessment Tools.

| Tool (Citation) | Place of Validation |

Population Tested |

Content Validity | Construct Validity | Predictive Validity | Reliability | Domains/Factors Identified |

| Workplace Breastfeeding Support Scale (Bai, Peng, & Fly, 2008) | Central Indiana, United States | 66 Mothers (6-12 months postpartum, worked outside home) | Four experts (specialists in nutrition, lactation, scale development, and survey instrument development) | Factor analysis of responses; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (0.71) | Not discussed | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77 | (1) Technical support, (2) breastfeeding friendly environment, (3) facility support, (4) peer support |

| Utilization of Support Network Questionnaire (Buckner & Matsubara, 1993) | Alabama, United States | 126 Mothers who desired to breastfeed their newborns | Lactation consultants/expert review | Not discussed | Not discussed | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93 | (1) Supply/demand principles and answering questions, (2) encouragement and supply/demand principles, (3) confidence and encouragement |

| Modified Breastfeeding Attrition Prediction Tool (Evans, Dick, Lewallen, & Jeffrey, 2004) | Southeast United States | 141 Pregnant women attending prenatal breastfeeding classes who planned to breastfeed | Adapted from Breastfeeding Attrition Prediction Tool (Janke, 1994, 1995) and Dick et al. (2002) | Not discussed | “A significant association existed between educational level and breastfeeding status” and having close relatives who breastfed | Internal consistency reliability = 0.753 | Not discussed |

| Supportive Needs of Adolescents Breastfeeding Scale (Grassley, Spencer, & Bryson, 2013) | 3 Urban hospitals in the United States | 101 New mothers ages 15-20 years old who intended to breastfeed | 8 Certified lactation consultants | Factor analysis; Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (0.74) | Not tested | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83 | Combinations of (1) instrumental, appraisal, and emotional support; (2) informational, appraisal, and emotional support; (3) “miscellaneous items about engaging the adolescents’ support persons” |

| Breastfeeding and Employment Study: Employee Survey (EPBSQ) (Greene & Olson, 2008; Greene, Wolfe, & Olson, 2008) | East Lansing, Michigan, United States (Michigan State University) | 104 Women who were pregnant or recently gave birth and planned to return to work full-time within 3 months of delivery | Literature review, 11 experts (licensed practitioners and researchers), interviews with 14 women who had breastfed during employment | Multidimensional Random Coefficients Multinomial Logit Model, a “multidimensional extension of the Rasch measurement model” | Not discussed | Reliability = 0.68-0.89 | (1) Company policies/work culture, (2) manager/coworker support |

| Perceived Breastfeeding Support Assessment Tool (Hirani, Karmaliani, Christie, Parpio, & Rafique, 2013) | Pakistan | 200 Breastfeeding working mothers | 7 Experts (lactation consultant, nutritionist, pediatric consultant, physician, nurse, psychologist) | Factor analysis: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (0.762); principal components analysis (eigenvalues > 1.00) | Workplace environmental support was higher for mothers with more education, who worked more hours, and who had maternal leave. Those with higher levels of workplace and social support were modeled to be more likely to continue breastfeeding while working. | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85 | (1) Workplace environmental support, (2) social environmental support |

| Hughes Breastfeeding Social Scale (Hughes, 1984) | Southeastern United States | 10 Breastfeeding primiparae | 6 Experts (pediatrician, pediatric resident, pediatric nurse practitioner/clinical specialist, and 3 registered nurses) | Spearman-Brown prophecy formula (0.85-0.89) | Not discussed | Alpha = 0.86, 0.88, 0.84 | (1) Emotional support, (2) instrumental support, (3) informational support |

| Matich and Sims Scale (Matich & Sims, 1992) | Central Pennsylvania, United States | 159 Pregnant women attending prenatal clinics and classes or Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children clinics | “Experts in nutrition and social support measurement” | Factor analysis, principal components analysis, and “orthogonal rotation of factors using the Varimax procedure” | Not discussed | Coefficient alphas = 0.88, 0.94, 0.93 | (1) Tangible support, (2) emotional support, (3) informational support |

Table 5.

Overview of Research Studies Using Knowledge and Attitudes Tool.

| Tool (Citation) | Study Author (Year) |

Purpose | Location | Results | Method of Adaptation, Translation, Cross-Cultural Equivalency, or Pretesting |

| Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire (Brodribb, Fallon, Jackson, & Hegney, 2008) | Srinivasan, Graves, & D’Souza (2014) | “To test the effectiveness of a 3-hour course on breastfeeding for family physicians” | Canada | Not discussed | “A modified version of the validated Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire was used,” although the nature of modification was not discussed. |

| Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (de la Mora, Russell, Dungy, Losch, & Dusdieker, 1999) | Charafeddine et al. (2015) | To assess the “psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the IIFAS (IIFAS-A)” | Beirut, Lebanon | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.640 | “After translating to classical Arabic and back-translating to English, the IIFAS-A was pilot tested among 20 women for comprehension, clarity, length, and cultural appropriateness.” |

| Srinivas, Benson, Worley, & Schulte (2015) | “To study the interaction of breastfeeding attitude and self-efficacy with the intervention,” aiming “to improve rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding at 1 and 6 months using a low-intensity peer counseling intervention beginning prenatally” | Cleveland, Ohio, United States | Not discussed | Used in original format | |

| Tuthill et al. (2016) | To construct a “consolidated instrument [that] was adapted to be culturally relevant and translated to yield more reliable and valid results for use in our larger research study to measure infant feeding determinants effectively in our target cultural context” | KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79-0.86 | The IIFAS was combined with other instruments to make one consolidated instrument, which was then “cross-culturally adapted utilizing a multi-step approach.” | |

| Twells et al. (2014) | “To assess the reliability and validity of the IIFAS in expectant mothers; to compare attitudes to infant feeding in urban and rural areas; and to examine whether attitudes are associated with intent to breastfeed” | Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80 | Used in original format | |

| Van Wagenen, Magnusson, & Neiger (2015) | To collect information on “U.S. men’s knowledge of and attitudes towards breastfeeding” in the context of social support | United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78 | Used in original format | |

| Preterm Infant Feeding Survey (Dowling, Madigan, Anthony, Elfettoh, & Graham, 2009) | Dowling, Shapiro, Burant, & Elfettoh (2009) | “To examine the factors involved in mothers’ decisions to provide breast milk for their premature infants and to determine if these factors differ between Black and White mothers” | Eastern United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84 | Used in original format |

| Dowling, Blatz, & Graham (2012) | “Examined differences in outcomes of provision of mothers’ milk before and after implementation of a single-family room (SFR) neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and described issues related to long-term milk expression” | Ohio, United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73-0.85 | Used in original format | |

| Breast Milk Expression Experience (Flaherman et al., 2013) | Flaherman et al. (2011) | “To compare bilateral electric breast pumping to hand expression among mothers of healthy term infants feeding poorly at 12–36 h after birth” | California, United States | Not discussed | Used in original format |

| Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool (BAPT) (Janke, 1992) | Gill, Reifsnider, Lucke, & Mann (2007) | “To describe a revised BAPT, administered antepartally, that measures intention to breastfeed” | Southwestern United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78-0.86 | “Was translated into Spanish and back-translated for accuracy. The BAPT was then revised by reducing the number of items to 35 (32 were used for analysis) and contracting the 6-point scale to 3 categories” |

| Joshi, Trout, Aguirre, & Wilhelm (2014) | “To explore factors that influence breastfeeding initiation and continuation among Hispanic women living in rural settings” and “to develop a framework for an educational breastfeeding program to meet the needs of Hispanic women living in rural settings” | Nebraska, United States | Not discussed | Nature of revisions not discussed | |

| Kafulafula, Hutchinson, Gennaro, Guttmacher, & Kumitawa (2013) | “To determine factors that influence HIV-positive mothers’ prenatal intended duration of exclusive breastfeeding and their likelihood to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months” | Malawi | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.858 | A modified form of the instrument called the Exclusive Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool was developed. | |

| Lewallen et al. (2006) | To create an adaptation of the BAPT with the same purpose of identifying women at risk for premature weaning based on breastfeeding attitudes, with the additional purpose of making the instrument easier to administer and score | North Carolina, United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85 | The 5-point Likert-type scale of the BAPT was modified to a dichotomous response format. | |

| Wambach et al. (2011) | “To test the hypotheses that education and counseling interventions provided by a lactation consultant-peer counselor team would increase breastfeeding initiation and duration up to 6 months postpartum, when compared to control conditions. We also explored the effects of the intervention on exclusive breastfeeding rates.” | Midwestern United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87-0.93 | Used in original format | |

| Breastfeeding Knowledge, Attitude, and Confidence Scale (Laanterä, Pietilä, & Pölkki, 2010) | Laanterä, Pölkki, Ekström, & Pietilä (2010) | “To describe Finnish parents’ prenatal breastfeeding attitudes and their relationships with demographic characteristics” | Southeastern Finland | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.602-0.858 | “Five breastfeeding experts evaluated the scale and no changes were made to the attitude items on the basis of their evaluations. The pretest was performed in February 2009. Minor changes such as alterations to the wording were made to the scale on the basis of the pretest.” |

| Breastfeeding Behavior Questionnaire (Libbus, 1992) | Libbus (2000) | To examine “attitudes toward breastfeeding in 57 Spanish-speaking Hispanic American women” | Midwestern United States | A test-retest reliability was reported as a correlational coefficient = .96 | Translated into Spanish, with content validity determined by Spanish-speaking health professionals |

| Libbus & Kolostov (1994) | “Investigated attitudes regarding breastfeeding in 69 low-income women presenting for prenatal care at a teaching facility in a small Midwest United States community” | Midwestern United States | A test-retest reliability was reported as a correlational coefficient = .88 | Used in original format | |

| Marrone, Vogeltanz-Holm, & Holm (2008) | “To examine university undergraduate women’s and men’s attitudes and knowledge toward breastfeeding” | North Dakota, United States | A test-retest reliability was reported, r = .88 | Used in original format | |

| Nabulsi et al. (2014) | “To investigate whether a complex intervention targeting new mothers’ breastfeeding knowledge, skills and social support within a Social Network and Social Support theory framework will increase exclusive breastfeeding duration among women in Lebanon” | Lebanon | Not discussed | The questionnaire used in the study was adapted from the Breastfeeding Behavior Questionnaire among others and then translated into Arabic and back-translated to English. |

Table 6.

Adaptation and Reliability of Breastfeeding Social Support Instruments in Novel Settings.

| Tool (Citation) | Study Author (Year) |

Purpose of Study | Setting | Reliability Results |

Method of Adaptation, Translation, Cross-Cultural Equivalency, or Pretesting |

| Workplace Breastfeeding Support Scale (Bai, Peng, & Fly, 2008) | Bai & Wunderlich (2013) | “To assess current lactation accommodations in a workplace environment and to examine the association between the different dimensions of support and the duration of exclusive breastfeeding” | New Jersey, United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84 | Combined with Employee Perceptions of Breastfeeding Support Questionnaire |

| Utilization of Support Network Questionnaire (Buckner & Matsubara, 1993) | None | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Modified Breastfeeding Attrition Prediction Tool (modified BAPT) (Evans, Dick, Lewallen, & Jeffrey, 2004) | Muslu, Basbakkal, & Janke (2011) | “To translate and psychometrically assess the BAPT (Turkish version) among women in Turkey” | Izmir, Turkey | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88 | Translated by four bilingual experts to Turkish, blind back-translation into English |

| Supportive Needs of Adolescents Breastfeeding Scale (Grassley, Spencer, & Bryson, 2013) | Pentecost & Grassley (2014) | “To explore the needs of adolescents for social support from nurses when initiating breastfeeding” | Southwestern United States | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83 (original instrument) | Added two open-ended questions |

| Employee Perceptions of Breastfeeding Support Questionnaire (Greene & Olson, 2008; Greene, Wolfe, & Olson, 2008) | Burks (2014) | “To investigate mothers’ perceptions of workplace breastfeeding support” | Northern New England, United States | Not discussed | Used in original format |

| Perceived Breastfeeding Support Assessment Tool (Hirani, Karmaliani, Christie, Parpio, & Rafique, 2013) | None | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hughes Breastfeeding Support Scale (Hughes, 1984) | McNatt & Freston (1992) | To answer: “(1) How does the amount of perceived support relate to a woman’s feelings of breastfeeding success? (2) Are certain types of support more related to a woman’s feelings of success? (3) Is the makeup of a woman’s support network structure related to her lactation outcome?” | Southwestern Connecticut | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 emotional, 0.88 instrumental, 0.84 informational support (original instrument) | Used in original format |

| Boettcher, Chezem, Roepke, & Whitaker (1999) | “To elucidate [a variety of factors] in an attempt to suggest a new strategy for encouraging longer breastfeeding duration in mothers both with and without prior breastfeeding experience” | Midwestern U.S. city | Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86 emotional, 0.88 instrumental, 0.84 informational support (original instrument) | Used in original format; administered along with the Measure of Interpersonal Dependency Scale (Hirschfeld et al., 1977) | |

| Matich and Sims Scale (Matich & Sims, 1992) | None | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note. N/A = not applicable.

Breastfeeding Attitudes and Knowledge Instruments

Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire

Overview.

The purpose of Brodribb, Fallon, Jackson, and Hegney’s (2008) Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire is to describe the relationship between breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes and duration of personal breastfeeding experience. No theoretical framework was discussed. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes and more knowledge regarding breastfeeding. The instrument has been used once since original development in an adapted format (Srinivasan, Graves, & D’Souza, 2014).

Validation.

Content validity was assessed by three doctors with breastfeeding experience and a researcher with a background in breastfeeding education. Construct validity was tested by administering the instrument to 161 Australian general practice registrars (residents by U.S. standards) in their final year of training. Reliability was demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 for the knowledge scale and 0.84 for the attitude scale, and item-total correlations of less than 0.2 for each scale. Predictive validity was not discussed.

Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale

Overview.

The purpose of de la Mora, Russell, Dungy, Losch, and Dusdieker’s (1999) Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) is to develop a measure of attitudes toward infant feeding through an easily administered instrument. A theoretical framework was not discussed. The IIFAS was tested in three separate studies on three different populations. Half of the items favored breastfeeding, and the remaining half favored formula feeding. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes toward breastfeeding. The instrument has been used at least 27 times since original development in both original and adapted formats (Dowling et al., 2012; Dowling, Madigan, Anthony, Elfettoh, & Graham, 2009; Dowling, Shapiro, Burant, & Elfettoh, 2009; Flaherman et al., 2013; Flaherman et al., 2011).

Validation.

Three separate studies were conducted for validation. Content validity was not discussed in any of the studies. Construct validity was tested by administering the instrument to 125 postpartum women in the first study, 130 postpartum women in the second study, and 725 postpartum women who had initiated breastfeeding while in the hospital in the third study. Reliability varied among the three studies and their different populations. In the first and second studies, reliability was relatively consistent with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 and 0.85. Reliability dropped in the third study with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.68 and an item-total correlation range of 0.07 to 0.45. Predictive validity showed that maternal attitudes toward breastfeeding were indeed a predictor of the mother’s choice of feeding method.

Preterm Infant Feeding Survey

Overview.

The purpose of Dowling, Madigan, et al.’s (2009) Preterm Infant Feeding Survey (PIFS) is to measure attitudes toward infant feeding in mothers of preterm infants. The PIFS was adapted from Janke’s (1992) Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool (BAPT). The BAPT focused on mothers of healthy, full-term infants; the PIFS was created to focus instead on preterm, hospitalized infants. Like the BAPT, the PIFS applies Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior as a theoretical framework, the major tenets of which are that “behavioral intention determines actual behavior, while outcome beliefs, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intention.” The BAPT was intended to measure five domains: beliefs and attitudes concerning breastfeeding and formula feeding, subjective norms, control beliefs, and two weighting scales for importance of attitudes and importance of attitudes of significant people. Higher scores indicate stronger or more positive beliefs and attitudes toward breastfeeding. The instrument has been used twice since original development in its original format (Dowling et al., 2012; Dowling, Shapiro, et al., 2009).

Validation.

Content validity was evaluated by five doctorally prepared nurses who had experience with mothers of preterm infants. Construct validity was tested by administering the instrument to 105 postpartum mothers of preterm infants. It was tested via exploratory factor analysis using principal axis factoring with oblimin rotation (eigenvalues > 1) and examination of scree plots of eigenvalues. Factor analysis resulted in a four-factor solution: negative breastfeeding sentiment, positive breastfeeding sentiment, subjective norms, and breastfeeding control. Reliability was indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80. Predictive validity showed scores that indicated that negative attitudes toward breastfeeding, lower subjective norm, and lower breastfeeding control were associated with premature weaning.

Breast Milk Expression Experience

Overview.

The purpose of Flaherman et al.’s (2013) Breast Milk Expression Experience (BMEE) is “to develop a measure to evaluate women’s experiences of expressing milk.” No theoretical framework was discussed. Items associated with negative breastfeeding experiences were reverse scored. Higher scores indicate better experiences with breastfeeding. The instrument has been used once since original development in its original format (Flaherman et al., 2011).

Validation.

Content validity was evaluated by an interdisciplinary panel of four content experts. The authors determined that their study did not have the statistical power to report on construct validity. The instrument was administered to 68 mothers immediately after postpartum milk expression. Reliability of the instrument was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.703. Predictive validity showed that higher scores were associated with greater likelihood of breast milk expression at 1 month.

Breast-feeding Attrition Prediction Tool

Overview.

The purpose of Janke’s (1992) BAPT is to identify women at risk for premature weaning based on breastfeeding attitudes. Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior was used as a theoretical framework to guide the development of the BAPT. The instrument was intended to measure three domains: attitudes, control, and subjective norms. The interpretation of the scores obtained from using the instrument was not mentioned. The instrument has been used eight times since original development in both original and adapted formats (Gill, Reifsnider, Lucke, & Mann, 2007; Joshi, Trout, Aguirre, & Wilhelm, 2014; Kafulafula, Hutchinson, Gennaro, Guttmacher, & Kumitawa, 2013; Lewallen et al., 2006; Wambach et al., 2011).

Validation.

Content validity was assessed by 10 lactation experts. Construct validity was tested by exploratory factor analysis, using the scree test for factor extraction and an orthogonal (Varimax) rotation for factor rotation, after administering the questionnaire to 157 mothers at 16 weeks postpartum. Factor analysis demonstrated a six-factor solution: negative breastfeeding sentiment, negative formula-feeding sentiment, positive breastfeeding sentiment, breastfeeding control, professional support, and support of family and friends. Reliability was demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80. Predictive validity was tested by determining if a significant difference in mean regression factor scores existed between women who were exclusively breastfeeding and those who had switched to exclusive formula feeding. The authors found that all but one factor of their instrument were significantly predictive of feeding method.

Breastfeeding Knowledge,Attitude, and Confidence Scale

Overview.

The purpose of Laanterä, Pietilä, and Pölkki’s (2010) Breastfeeding Knowledge, Attitude, and Confidence Scale is to assess breastfeeding knowledge of parents and its related demographic variables. No theoretical framework was discussed. Most, but not all, of the knowledge items were negatively worded so that common misconceptions regarding breastfeeding could be included. The instrument was intended to measure three domains: knowledge, attitude, and confidence. Higher scores indicate greater knowledge. The instrument has been used once since original development in an adapted format (Laanterä, Pölkki, Ekström, & Pietilä, 2010).

Validation.

Content validity was assessed by five breastfeeding experts who were health care officials acquainted with breastfeeding counseling. Construct validity was tested by administering the instrument to 123 pregnant mothers and 49 fathers. Reliability of the instrument was demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. Item-total correlations ranged from 0.215 to 0.604, and 70% of the correlations were above 0.30. Predictive validity of the instrument was not discussed.

Breast-feeding Attitude Scale

Overview.

The Breast-feeding Attitude Scale (BrAS) (Lewallen et al., 2006) was created as an adaptation of the BAPT (Janke, 1992) with the same purpose of identifying women at risk for premature weaning based on breastfeeding attitudes in addition to making the instrument easier to administer and score. No theoretical framework was discussed. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes toward breastfeeding. The BrAS has not been used in other studies.

Validation.

Content validity was not discussed. Construct validity was tested by administering the instrument to 108 postpartum mothers. Reliability was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85. The authors considered the predictive validity of the BrAS to be sufficient in that the instrument was able to predict breastfeeding initiation by distinguishing between mothers who initiated breastfeeding and those who chose formula feeding. However, the authors found that the BrAS was unable to predict breastfeeding duration, as it could not distinguish between mothers who would continue breastfeeding and those who would wean early.

Breastfeeding Behavior Questionnaire

Overview.

The purpose of Libbus’ (1992) Breastfeeding Behavior Questionnaire (BBQ) is to examine the attitudes and beliefs that affect infant-feeding choice among different demographics. No theoretical framework was discussed. A lower score indicates more positive attitudes and more accurate knowledge concerning breastfeeding. The instrument has been used four times (twice by the instrument’s creator) since original development in original and adapted formats (Libbus, 2000; Libbus & Kolostov, 1994; Marrone, Vogeltanz-Holm, & Holm, 2008; Nabulsi et al., 2014).

Validation.

Content validity was assessed by a panel of local experts in nutrition and nursing. Original testing was conducted by administering the instrument to 17 pregnant previous or current breastfeeders. Results from this study compared breastfeeding attitudes between members of La Leche League and those in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Results showed that those in the La Leche League group saw more favorable attitudes and accurate information toward breastfeeding. Reliability and predictive validity of the BBQ were not discussed.

Breastfeeding Social Support Instruments

Workplace Breastfeeding Support Scale

Overview.

The purpose of Bai, Peng, and Fly’s (2008) Workplace Breastfeeding Support Scale is to measure a mother’s perception of breastfeeding support in her workplace. No theoretical framework was discussed, and specific intended domains for measurement were not mentioned. Higher scores indicate more positive workplace breastfeeding support. The instrument has been used once since original development in an adapted format (Bai & Wunderlich, 2013).

Validation.

Four experts in nutrition, lactation, scale development, and survey instrument development, respectively, tested the content validity of the instrument. The construct validity was tested with 66 pregnant or 6- to 12-month postpartum mothers who worked outside the home. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (0.71) was used for factor analysis and resulted in a four-factor solution: technical support, breastfeeding-friendly environment, facility support, and peer support (Dziuban & Shirkey, 1974). Reliability was demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77. The predictive validity of the instrument was not discussed.

Utilization of Support Network Questionnaire

Overview.

The purpose of Buckner and Matsubara’s (1993) Utilization of Support Network Questionnaire is to determine the functions of various support resources to determine effective nursing interventions that promote breastfeeding in new mothers. No theoretical framework is discussed. Higher scores indicate more social support. The items concern seven different support groups including lactation consultants, husbands, and friends. The instrument has not been used since original development.

Validation.

The content validity was conducted by lactation consultants and expert review. Construct validity was not discussed. Reliability was demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. Predictive validity was not discussed.

Modified Breastfeeding Attrition Prediction Test

Overview.

The purpose of Evans, Dick, Lewallen, and Jeffrey’s (2004) Modified Breastfeeding Attrition Prediction Test (modified BAPT) is to predict new mothers’ breastfeeding attrition prior to 8 weeks based on breastfeeding attitude, social support, and control. The original BAPT is based on the theoretical framework of Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Janke, 1992). The original and modified BAPT are separated into four domains: the positive breastfeeding sentiment attitudinal scale, negative breastfeeding sentiment attitudinal scale, social and professional support scale, and breastfeeding control scale. Higher scores indicate greater breastfeeding support. The instrument has been used once since original development in an adapted format (Muslu, Basbakkal, & Janke, 2011).

Validation.

Content validity was not discussed, most likely because it was modified from a pre-existing instrument (Janke, 1992). The method of testing construct validity was not discussed. Reliability was demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.753 and 0.851 for the prenatal and postpartum time periods, respectively, among 117 new mothers. Predictive validity was tested in the postpartum period, and mothers who had a higher education level (i.e., control) and close relatives who breastfed (i.e., social support) had a lower rate of breastfeeding attrition.

Supportive Needs of Adolescents Breastfeeding Scale

Overview.

The purpose of Grassley, Spencer, and Bryson’s (2013) Supportive Needs of Adolescents Breastfeeding Scale (SNABS) is to measure adolescent perceptions of nurse support when initiating breastfeeding. The theoretical framework of the instrument is based on House’s Theory of Social Support, which conceptualizes support as the four areas of emotional, informational, instrumental, and appraisal support (LaRocco, House, & French, 1980). The scale is divided into four domains based on 25 supportive nurse behaviors: informational, instrumental, emotional, or appraisal support. Higher scores indicate greater support to pregnant adolescents from nurses. The instrument has been used once since original development in an adapted format (Pentecost & Grassley, 2014).

Validation.

Eight certified lactation consultants evaluated the content validity of the SNABS. Factor analysis using a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test was used to test construct validity on 101 15- to 20-year-old new mothers. Factor analysis resulted in a three-factor solution: instrumental, appraisal, and emotional support (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81), informational, appraisal, and emotional support (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76), and “miscellaneous items about engaging the adolescents’ support persons and providing immediate skin-to-skin care” (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68). Reliability was demonstrated with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. Predictive validity was not discussed.

Employee Perceptions of Breastfeeding Support Questionnaire

Overview.

The purpose of Greene, Wolfe, and Olson’s (2008) Employee Perceptions of Breastfeeding Support Questionnaire (EPBSQ) is to measure working new mothers’ perspectives of workplace breastfeeding support. The EPBSQ is based on the theoretical framework of Glanz’s social ecological model that emphasizes how multiple layers of influences affect health behaviors (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008). The EPBSQ measured the five domains of company, manager, coworkers, workflow, and physical environment. The instrument has been used once since original development in its original format (Burks, 2014).

Validation.

Content validity was evaluated by 10 lactation experts, an evaluation design expert, and 14 women working in Michigan who had delivered within the past year. Construct validity was tested with 117 women who worked in Michigan and were pregnant or had given birth within the past year using the Multidimensional Random Coefficients Multinomial Logit Model of the Rasch measurement model (Wright & Mok, 2000). Reliability of separation values for the instrument’s subscales—(1) company policies/work culture and (2) manager/coworker support—is between 0.68 and 0.89. Predictive validity was not discussed.

Perceived Breastfeeding Support Assessment Tool

Overview.

The purpose of Hirani, Karmaliani, Christie, Parpio, and Rafique’s (2013) Perceived Breastfeeding Support Assessment Tool (PBSAT) is to measure urban Pakistani working mothers’ perceptions of breastfeeding support. The theoretical framework uses Bronfenbrenner’s (2009) Ecological Systems Theory, which states that various ecological systems influence human development. The instrument is divided into four domains: informational support, social support, health care support, and workplace environmental support. Meaning of the score was not discussed. The instrument has not been used since original development.

Validation.

Seven experts including a lactation consultant, nutritionist, pediatric consultant, physician, nurse, and psychologist tested the content validity of the instrument. Construct validity was tested through a factor analysis consisting of a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test, principal components analysis, and Varimax (rotation with Kaiser normalization) on 20 working, breastfeeding mothers. Factor analysis revealed 12 factors (eigenvalues > 1). After additional screening, two domains emerged: workplace environmental support and social environmental support. Reliability was demonstrated with internal Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 and 0.77, respectively, and 0.85 in total. Predictive validity shows that mothers who are more educated, work more hours, and have maternal leave perceive higher levels of workplace support and that those mothers with higher levels of environmental and workplace social support are more likely to continue breastfeeding with employment.

Hughes Breastfeeding Support Scale

Overview.

The purpose of Hughes’ (1984) Hughes Breastfeeding Support Scale (HBSS) is to measure various types of support that breastfeeding mothers receive. The theoretical framework of the instrument is based on the Theory of Social Support by Cobb (1979) and House (1981), which emphasizes that the usefulness of social support is dependent on the recipient’s perception (LaRocco et al., 1980; Riley, Abeles, & Teitelbaum, 1979). The HBSS is divided into three domains: emotional, instrumental, and informational breastfeeding support. Higher scores indicate more social support. The instrument has been used three times since original development in both original and adapted formats (Boettcher, Chezem, Roepke, & Whitaker, 1999; Hirschfeld et al., 1977; McNatt & Freston, 1992).

Validation.

A pediatrician, pediatric resident, three registered nurses, and a pediatric nurse practitioner and clinical specialist reviewed the content validity of the instrument. Construct validity was tested on 30 breastfeeding mothers in the southeastern United States using the Spearman-Brown prophecy formula. Reliability was demonstrated for the three factors by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 for emotional, 0.88 for instrumental, and 0.84 for informational support. Predictive validity was not discussed.

Matich and Sims Scale

Overview.

The purpose of Matich and Sims’ (1992) scale is to discover various aspects of social support perceived by women in Pennsylvania during their last trimester of pregnancy and 3 to 4 weeks after breastfeeding. No theoretical framework was discussed. The instrument is divided into three domains: tangible, emotional, and informational support. Higher scores indicate increased levels of support from a variety of individuals including the baby’s father, relatives, and physicians. The instrument has not been used since original development.

Validation.

Experts in the fields of nutrition and social support measurement assessed the content validity of the instrument. Testing for construct validity was conducted with factor analysis, principal components analysis, and orthogonal rotation factors on 85 women who intended to breastfeed and 74 women who intended to bottle feed. Factor analysis resulted in a three-factor solution: tangible, emotional, and informational support. Reliability was demonstrated by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, 0.93, and 0.94, respectively. Predictive validity was not tested.

Discussion

Although each of these instruments offers strengths, some are more robust or appropriate than others.

Theoretical Framework

Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior was the most widely applied. It was used by three of eight attitudes and knowledge instruments and one of eight social support instruments (Ajzen, 1991). Two social support instruments incorporated socioecological frameworks congruent (Bronfenbrenner, 2009) with the multilevel attributes of social support. However, the majority of instruments (i.e., five attitudes and knowledge; four social support) did not mention any theoretical framework. The omission of a description of theoretical underpinnings is a weakness in these respective instruments (see Tables 1 and 2) (Grant & Osanloo, 2014).

Domains

A well-developed instrument should not only be based on a theoretical framework, but the relevant domains or constructs (also reported as factors by some authors) should be articulated. The elaboration of domains being measured helps researchers understand the meaning behind instrument results. Presumably, all instruments intended to measure components of attitudes, knowledge, or social support; however, the lack of explanation regarding the conceptual and operational definitions behind item development and the domain that each item was intending to measure makes interpretation of instrument results and its adaptation more challenging.

Only two attitudes and knowledge instruments identified domains (i.e., breastfeeding sentiment, breastfeeding control from the PIFS; breastfeeding sentiment, professional support, and family support from the BAPT), which represents a major comparative advantage of these instruments. It is interesting that the domains were similarly defined, which may be attributed to the fact that both used Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior as their theoretical framework.

All but one (i.e., modified BAPT) social support instrument discussed domains in their instrument development process. Given that social support comes from many different venues (e.g., workplace, family), selecting a suitable social support instrument is highly germane to the research topic. Thus, taking domains into consideration is one point of consideration when evaluating existing social support instruments for future work.

Validity

Instruments with both strong content and construct validity are obviously more likely to be measuring intended constructs. For all instruments, nurses, lactation experts, or nutrition experts were the professionals called upon to evaluate content validity with varying degrees of intensity. However, two out of eight attitudes and knowledge instruments (i.e., IIFAS, BrAS) failed to describe content validity (see Table 3), which is a major weakness (all of the social support instruments discussed content validity) (see Table 4).

Lack of assessment of construct validity means that we cannot know if the instrument is valid and decreases our ability to critique if the instrument is measuring its intended domains. It also diminishes our ability to evaluate the reliability of the data; given data with strong reliability but lacking validation may mean that the data are showing reliable strength toward a construct that is unknown. Four of the eight attitudes and knowledge instruments did not discuss construct validity; however, reliability of the data was reported for all instruments. An omission of complete construct validity (i.e., factor analysis) leads to instrument development research results being less confident of meaningful results in an adapted version.

In contrast, of the social support instruments, all but two (i.e., Utilization of Support Network Questionnaire, modified BAPT) reported on the construct validity. All but one (i.e., EPBSQ) reported a Cronbach’s alpha and otherwise all had Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ≥ 0.80, except for the BAPT (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75), indicating stronger internal consistency among all social support instruments. The IIFAS has been adapted for use in other settings more than any other attitudes and knowledge scale (see Table 5). Although the IIFAS had some limitations in original testing, subsequent adaptations reported higher, but not ideal, reliability of the data from 0.73 to 0.86.

Predictive validity was discussed in four attitudes and knowledge instruments (i.e., IIFAS, PIFS, BMEE, BAPT). Predictive validity was evaluated based on certain breastfeeding behaviors, such as initiation, duration, early weaning in preterm infants, or human milk expression. The four instruments evaluating if their items predicted breastfeeding behavior had strong results (see Table 5), showcasing how that instrument may be used for screening or proactively targeting individual-level attitudes and knowledge to ensure greater breastfeeding practice.

Only two social support instruments looked at predictive validity; that is, the proportion of relatives who breastfed (for the modified BAPT) and the supportiveness of the workplace environments and social support (i.e., PBSAT) were indeed predicted by the respective scales. Researchers interested in these specific components to predictive outcomes from breastfeeding attitudes and knowledge or social support may find an instrument with strong predictive validity results more useful (i.e., IIFAS, PIFS, BMEE, BAPT, modified BAPT, PBSAT). Testing predictive validity provides valuable feedback on how the constructs being measured in the instrument affect actual breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., initiation, duration) and strengthen the instrument development process.

Number of Items

An instrument’s number of items has great implications for its likelihood of adaptation by researchers, mostly due to participant burden and resources required to administer and analyze (McCoach et al., 2013). Half of all instruments had 10 to 20 item numbers, whereas three attitudes and knowledge instruments had 78 or more items, which is more or less unrealistic in most settings. A longer instrument is not always more informative, and a factor analysis of initial scale items may be useful for paring down items prior to widespread implementation.

Adaptation

Adaptability is an important consideration in choosing an instrument to use in a novel setting. For attitudes and knowledge, six of eight instruments were adapted by authors in other settings at least once. The IIFAS and BAPT have been used many times outside of their original setting (e.g., Lebanon, South Africa, Canada, Malawi, Continental United States), whereas others (i.e., Australian Breastfeeding Knowledge and Attitude Questionnaire, PIFS, BMEE) have been adapted within a similar population to the original development testing by the original author (de la Mora et al., 1999; Janke, 1992). In addition, despite the lack of reports on original validity results, authors adapting the BBQ reported strong test-retest reliability findings. This reporting enhances the field’s overall knowledge and confidence in the BBQ, and more generally, research adapting existing instruments can add to the field’s body of knowledge by reporting on validation testing and reliability.

For social support instruments, only half have been adapted, with the HBSS being the most frequent (two times). The variation in types of social support needed (e.g., family, friends, workplace) may account for the lack of adaptation or use in novel settings. The IIFAS has been adapted more than any other instrument; however, data from these adaptations (in addition to original testing) show some weaknesses (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha = 0.64, Charafeddine et al., 2015; 0.79, Van Wagenen, Magnusson, & Neiger, 2015) in reliability results. In addition, language/concepts used in the IIFAS may be confusing or too advanced for some populations (e.g., “weaned” and “nutritional benefits”). Reasons for this more frequent adaptation could be for the ability to compare across sites or that its items are relevant in many settings. Rigorous cross-cultural adaptation ensures a more meaningful instrument when choosing to use any existing instrument in novel settings.

Conclusion and Practice Guidelines

In conclusion, although there are a multitude of instruments available for the assessment of attitudes and knowledge and social support, there is no clear best one. We can, however, offer some considerations when selecting and implementing these assessments. We recommend that researchers answer the following questions as they select the scale that best fits their needs.

Purpose: What is the purpose of the assessment?

A first step in instrument selection is to identify the purpose of the measurement. This means to clarify the outcome of interest (e.g., any breastfeeding, EBF). The specificity of some of these instruments makes it very clear that one could be more fitting if the purposes match the interest, for example, adolescent breastfeeding attitudes or intention in the prenatal period. However, the lack of demonstrated validity/reliability for some of these should give pause to uncritical adaptation.

Defining purpose also means to be clear about the target audience (e.g., policy makers, expectant parents, clinicians) for this information and what the data will be used for (e.g., monitor at-risk dyads, assess changes in behavior over time, measure program effect, evaluate programs and policies, or advocacy). This will help to identify the data that will be most compelling.

Comparability: How important is comparability?

For the ability to compare levels of social support, attitudes, or knowledge across settings, it is ideal to use instruments that have been previously used. Should any national- or international-level endeavors to assess this occur, it will be very important to harmonize instruments to collect analogous data.

Validation: Are you measuring what you think you are measuring?

Validity testing is critical to report for both original instrument development and cross-cultural adaption of an existing instrument. In this review, construct validity was reported in varying degrees of depth and methodologies. A systematic approach to testing that includes content and construct validity as well as reliability and the depth of reporting such results would make comparisons across instruments and the adaptation of them more feasible (instrument development and psychometric testing are outlined by McCoach et al., 2013).

Likewise, adapting an instrument cross-culturally requires validation among the target population. This is a procedure that is often unclear to health researchers and clinicians. This process includes testing the adapted version with a sample of the population of interest and performing construct validity analysis (e.g., factor analysis and Cronbach’s alpha). Sample size is dependent on the number of constructs being measured and the items making up that construct (see McCoach et al., 2013, as a guide). Disseminating the process of and findings from cross-cultural adaptation can build knowledge in the field as well as serve as a guide for other researchers considering adapting an existing instrument. Using multiple validation steps to ensure effective translation and cultural fit is considered best practice (Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, & Ferraz, 2000).

Resources to implement: How much money, participant time, and analytic skill do you have?

Time to administer and effort to analyze are another consideration. Administering a 78-item questionnaire measuring one construct is often impractical. In a study measuring multiple constructs, the number of items that effectively measures one is an important consideration in order to reduce participant burden.

Implications for Future Research

As future work on scale development occurs, we would also make several pleas. First, each scale created should report (1) how the instrument was developed, including its purpose, theoretical framework, constructs being measured, and their conceptual and operational definitions, and (2) how the instrument was tested, including methodology for testing (i.e., sample, setting, how instrument was administered) and psychometric results, including validity (content, construct, predictive) and reliability.

Second, each scale being adapted should report (1) an overview of the existing instrument being adapted, (2) cross-cultural adaptation methodology undertaken, (3) adaptations or changes made to the original instrument, results from translation, or content validity index scoring, and (4) findings from psychometric testing of the adapted instrument. They should also publish the scales as online supplemental material. In the case of this review, obtaining the original scales was difficult or, for some, impossible.

In sum, by laying out that which is currently available for adaptation and use by researchers and practitioners and suggesting considerations with subsequent scale implementations, it is our intention that this review will facilitate the improved assessment of these important determinants of breastfeeding.

Acknowledgments

ELT and SLY were supported by F31MH099990 and K01 MH098902, respectively, from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]