The U.S. faces a daunting opioid epidemic that the Trump administration declared a “Public Health Emergency” (PHE) on October 26, 2017, now extended through April 24, 2018. There is some justification for declaring a PHE, or an urgent situation requiring immediate action to avoid serious harm.1 Nevertheless, the federal government appears to be largely conducting business as usual, neglecting to implement emergency actions to supplement the earlier-enacted 21st Century Cures Act and Combatting Addiction and Recovery Act that have longer-term goals. A recent Congressional infusion of $6 billion over 2 years can begin to triage opioid emergencies if allocated towards these purposes. However, the epidemic, whose burdens cost the U.S. $115 billion in 2017 and are projected to cost $200 billion by 2020, requires much greater funds, quickly.2 The failure to urgently act threatens to delegitimize PHE powers1 and foregoes the opportunity to address acute opioid-induced harms.

We propose that four opioid-related “emergencies” meet the PHE criteria. First, opioid-related deaths are rising at unprecedented rates, with over 116 Americans fatally overdosing per day in 2016.3 Second, HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) infectious disease transmissions have recently spiked. Third, the number of children in foster care is rising after a longstanding decline. Finally, the provision of evidence-based opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment, or medication-assisted therapy (MAT), that could help to avert future growth in these outcomes remains scant, particularly in rural America. PHE powers and money in the Public Health Emergency Fund (“Fund”) alone are insufficient, and additional steps and appropriations are required.

Opioid-Related Overdoses

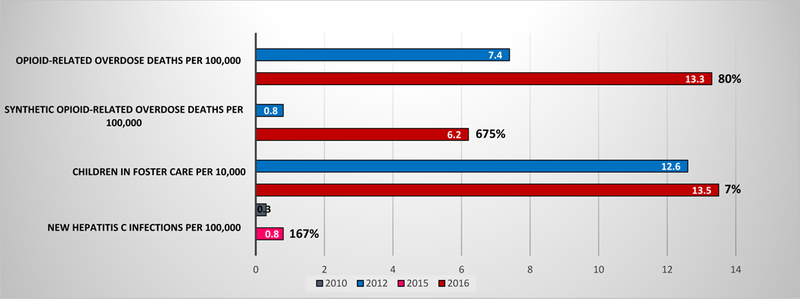

Although drug-related overdoses increased at a rate of 9% per year from 1979–2015,4 this death rate—attributable increasingly to heroin and synthetic opioids (figure)—increased by 21.4% from 2015 to 2016.3 The most direct means of averting overdose deaths is to expand access to naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug with high effectiveness when quickly and appropriately administered. Some states and communities have expanded naloxone access by equipping first responders, family and friends with the drug. Nevertheless, the naloxone dose required to reverse synthetic-related overdoses is at least 5 times greater than that typically available, so product and distribution restructuring is required.

Figure. Opioid Public Health Emergency Rates and Percent Increases, 2010-2016.

Notes: Percents are the percent increase from 2012 to 2016 for all outcomes, except for New Hepatitis C Infections per 100,000, which is the percent increase from 2010 to 2015. Drug overdose deaths were classified using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), based on the ICD-10 underlying cause-of-death codes X40–44 (unintentional), X60–64 (suicide), X85 (homicide), or Y10–Y14 (undetermined intent). Among the deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause, opioid-related overdose deaths were identified using the following ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death codes: opium (T40.0), heroin (T40.1), natural and semi-synthetic opioids (T40.2), methadone (T40.3), synthetic opioids excluding methadone (T40.4), or other and unspecific narcotics (T40.6). For 2016, the opioid-related overdose deaths may represent an undercount, because they do not include the following ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death codes: opium (T40.0), and other and unspecific narcotics (T40.6). Among deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause, synthetic opioid-related overdose deaths (other than involving methadone) were identified using the following ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death code: T40.4.

Sources:

Hedegaard H, Warner M, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 294. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm.

Children in Foster Care: Office of the Administration for Children and Families, Adoption and Foster Care Statistics, 1999–2016 data, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/afcars.

New Hepatitis C Infections: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Viral Hepatitis Statistics and Surveillance, Hepatitis C Virus, 1992–2015 data, https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/index.htm.

Since 2013, national spending on naloxone has grown from $10.5 to $108.6 million in the second quarter of 2017.1 Growth in the share of overdoses involving potent synthetic opioids and the population with OUDs (around 2.5 million) mean naloxone demand is increasing.5 Yet federal funding lines devoted towards naloxone have remained steady for 2017 and 2018.5 Conservatively estimating that, on average, 14.55 naloxone doses dispensed result in an opioid-overdose life saved, millions of additional doses are needed at costs that overwhelm state resources.6 Congressional appropriation of money into the Fund or otherwise could immediately facilitate naloxone purchases and training.

Infectious Disease Transmission

Rising opioid use, particularly with injected illicit sources like heroin, has been linked to HIV and HCV outbreaks. Nationwide, new HCV infections have risen 167% since 2010 after decreasing by 87% from 1992–2009 (figure). Using clean syringes for every injection, including at supervised syringe exchange programs that facilitate substance use treatment and naloxone access, is an evidence-based approach to reducing infectious disease transmission.

The federal government could promote clean syringes via rapid appropriations. Providing the 700,000 persons with heroin use disorders who are potentially injecting5 with needle exchange access at a price of about $20 per person would cost $14 million. Alongside funding, the Department of Justice could indicate that it will not prosecute Controlled Substances Act crimes of being in possession of illicit drugs at needle exchange programs.

Foster Care

After declining by almost 30% from 1999–2012, the number of children in foster care rose nationally by 7% between 2012 and 2016 (figure)—largely owing to parents’ opioid-related overdoses. The states with the 5 highest rates of additions to the foster care system also have opioid mortality rates well above the national average.2 Immediate steps to address this influx of orphans include reversal of opioid-related overdoses using naloxone and increasing MAT provision. Money from the Fund or federal supplemental grants could also assist depleted state foster care systems. There were approximately 40,000 new foster care cases in 2016 compared to 2012, and maintaining a foster child costs about $19,000 per year.7 Thus, the acute opioid epidemic impact on the foster care system is roughly $760 million.

Rural MAT

Finally, MAT has a strong evidence base and holds the potential to avert opioid-related overdoses, orphans, and infectious disease transmissions. Although addiction is a chronic disease and treatment a long-term prospect, certain acute steps would jump-start treatment initiation and address severe rural shortages. Roughly a quarter of those with OUDs receive treatment. Compared to urban counties, significantly higher percentages of rural counties lack any substance abuse treatment facility (55%), opioid treatment program (over 90%), or buprenorphine provider (72%).5 MAT costs impose additional barriers, especially in states that chose not to expand Medicaid.

In addition to many of the strategies recommended to increase naloxone, federal actions to address severe rural MAT provider shortages under the PHE include to: (1) deploy federally funded public health personnel to provide MAT, and (2) allow telemedicine providers to prescribe buprenorphine without performing an in-person examination. If President Trump, concurrently with the PHE, declared a “National Emergency” under the Stafford Act or the National Emergencies Act, HHS could further facilitate MAT by: relaxing the DATA 2000 waiver requirements for buprenorphine prescribing, and waiving some provisions of 42 C.F.R. Part 2 to facilitate timely, integrated addiction treatment.

The current administration appropriately drew national attention to the opioid epidemic by declaring it a PHE, but symbolism alone will not triage acute opioid-related harms experienced daily. The primary shortcoming of this PHE is the virtual absence of funds available to address the epidemic’s emergency components. The magnitude of current appropriations is small relative to the epidemic’s costs. Although many longer-term actions—including prescriber education, pain therapy alternatives, heightened oversight of illicit opioids, and robust addiction therapy—are needed, emergency steps can and should be taken to address the opioid-related imminent harms.

Acknowledgments.

Dr. Haffajee’s work on this article was supported by funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (#KL2TR002241) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the University of Michigan Injury Center (#3R49CE002099–05S1). Dr. Frank’s work on this article was supported by general institutional funds. Drs. Haffajee and Frank each contributed to the conception and content of the paper. Dr. Haffajee generated the first draft of the manuscript, and both authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest. Neither of the authors has relevant financial interests or relationships with entities in the bio-medical arena that could be perceived to influence, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing, this submitted work.

Authors’ tabulations from Iqvia data from all distribution channels.

Author’s tabulations from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC WONDER Multiple Cause of Death, 2013–2015 data, https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D77 and Office of the Administration for Children and Families, Adoption and Foster Care Statistics, 1999–2016 data, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/afcars.

Contributor Information

Rebecca L. Haffajee, Department of Health Management and Policy, University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Richard G. Frank, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Haffajee R, Parmet WE, Mello MM. What Is a Public Health “Emergency”? N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):986–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altarum. Economic Toll Of Opioid Crisis In U.S. Exceeded $1 Trillion Since 2001. https://altarum.org/about/news-and-events/economic-toll-of-opioid-crisis-in-u-s-exceeded-1-trillion-since-2001. Published 2018. Accessed February 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedegaard H, Warner M, Minino AM. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(294):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanich JM, Balmert LC, Burke DS. Exponential growth of the USA overdose epidemic. bioRxiv. 2017;(1):1–7. doi: 10.1101/134403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The President’s Commission on Combatting Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. Final Report of The President’s Commission on Combatting Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank RG, Fry CE. Medicaid Expands Access to Lifesaving Naloxone. The Commonwealth Fund: To the Point. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2017/jul/medicaid-helps-expand-lifesaving-naloxone. Published 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zill N Better prospects, lower cost: The case for increasing foster care adoption. Adopt Advocate. 2011;(35):1–7. https://www.adoptioncouncil.org/files/large/9422a636dfac395. [Google Scholar]