Abstract

At its discovery, orexin/hypocretin (OX) was hypothesized to promote food intake. Subsequently, with the identification of the participation of OX in numerous other phenomena, including arousal and drug seeking, this neuropeptide was proposed to be involved in highly motivated behaviors. The present review develops the hypothesis that the primary evolutionary function of OX is to promote foraging behavior, seeking for food under conditions of limited availability. Thus, it will first describe published literature on OX and homeostatic food intake, which shows that OX neurons are activated by conditions of food deprivation and in turn stimulate food intake. Next, it will present literature on excessive and binge-like food intake, which demonstrates that OX stimulates both intake and willingness to work for palatable food. Importantly, studies show that binge-like eating can be inhibited by OX antagonist s at doses far lower than those required to suppress homeostatic intake (3 mg/kg vs. 30 mg/kg), suggesting that an OX-based pharmacotherapy, at the right dose, could specifically control dysregulated eating. Finally, the review will discuss the role of OX in foraging behavior, citing literature which shows that OX neurons, which are activated during the anticipation of food reward, can promote a number of phenomena involved in successful foraging, including food-anticipatory locomotor behavior, olfactory sensitivity, visual attention, spatial memory, and mastication. Thus, OX may promote homeostatic eating, as well as binge eating of palatable food, due to its ability to stimulate and coordinate the activities involved in foraging behavior.

Keywords: binge, fat, palatable, reinstatement, seeking, sucrose

1. Introduction1

In the very first papers describing its discovery, the neuropeptide, orexin/hypocretin (OX), was suggested to play a major role in food intake and energy homeostasis (de Lecea et al 1998, Sakurai et al 1998). Since that time, now twenty years ago, hundreds of articles have followed up on this idea in numerous species, confirming the involvement of OX in normal eating and extending the findings to excessive intake of palatable foods (Barson and Leibowitz 2017). Simultaneously, researchers have identified an important role for OX in other behaviors such as the promotion of waking as well as drug seeking (Barson and Leibowitz 2017, Mahler et al 2014, Mieda 2017). With its varied behavioral effects, the precise underlying role of OX remains elusive. Several laboratories have hypothesized that OX serves to promote motivation in highly salient environmental contexts, and have suggested that an OX-based pharmacotherapy could be ideal for treating behaviors like reinstatement of extinguished drug seeking (Espana 2012, James et al 2017, Moorman 2018), as it would affect excessive but not homeostatic behavior. Interestingly, research reviewed here on the role of OX in feeding, even dysregulated feeding that resembles addiction, indicates that the conditions under which OX promotes this behavior are different than those under which it promotes drug use. Here, it is proposed that the primary evolutionary function of OX is to promote foraging behavior, seeking for food under conditions of limited availability. As such, OX (primarily through the orexin 1 receptor (OX1R) in the limbic system) can promote binge-like intake of energy-dense food but, in contrast to its role in drug relapse, it appears to play a minimal role in reinstatement of seeking for food that may no longer be available. Indeed, with OX known to promote arousal as well as feeding, it is notable that both humans and animals, during conditions of food deprivation, show elevated levels of OX, along with progressively shorter episodes of sleep and increased locomotor activity (Almeneessier et al 2018, Barson and Leibowitz 2017, Lauer and Krieg 2004, Sakurai et al 1998). Thus OX, during periods of limited access to food, appears to stimulate seeking or working for food as a survival strategy. In contrast, OX may stimulate reinstatement of extinguished drug seeking (where access has been entirely discontinued) due to a dysregulation of the system. Despite these contrasting roles for OX in aspects of food and drug use, studies suggest that an OX-based pharmacotherapy could nevertheless be effective in controlling problematic behaviors such as excessive food intake. The focus of the present review will be on the role of OX in normal and dysregulated eating and on the possible efficacy of an OX-based pharmacotherapy for problematic eating behavior. It takes the perspective that this ability of OX to promote eating is ultimately due to the underlying role of OX in promoting foraging behavior.

2. Anatomy of the orexin/hypocretin system

The OX system can be examined through its gene, peptides, or receptors. The 130-amino acid OX precursor gene is well-conserved across species, including rats, mice, sheep, fish, non-human primates, and humans (Archer et al 2002, Brown et al 2013, de Lecea et al 1998, Horvath et al 1999, Huesa et al 2005, Kaslin et al 2004, Sakurai et al 1998, Sakurai et al 1999). The gene encodes two different peptides, the 33-amino acid orexin-A (OX-A) and the 28-amino acid orexin-B (OX-B), which are 46% identical in their sequence (Sakurai et al 1998). The two OX peptides have differing binding affinities for the two OX receptors. While OX-A binds with nearly equal affinity to the OX1R and the orexin 2 receptor (OX2R), OX-B binds almost exclusively to the OX2R, with roughly the same affinity for this receptor as OX-A (Sakurai et al 1998). Both receptors are primarily neuroexcitatory in the brain (eg. (Blasiak et al 2015, Chen et al 2017, Gao et al 2017, Palus et al 2015)), although they have been found to interact with Gq, Gs, and Gi proteins (Magga et al 2006, Tang et al 2008), and they are located both pre- and post-synaptically (van den Pol et al 1998). Notably, the two receptors often predominate in different brain regions. For example, the OX1R but not OX2R is present in the locus coeruleus and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, while the OX2R but not OX1R is found in the central medial thalalmus and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (Trivedi et al 1998). Thus, OX may work similarly across species and the OX peptides may have distinct effects in the brain.

Neurons transcribing OX comprise a cluster of only a few thousand cells (estimates for the rat range from 1100 to 6700) (Allard et al 2004, Kessler et al 2011, Modirrousta et al 2005, Peyron et al 1998), but they project broadly through the brain to affect behavior (Peyron et al 1998). These neurons lie almost exclusively within the hypothalamus, spanning its perifomical, lateral, dorsomedial, and posterior regions, but a few OX cells are also located in the subthalamus (de Lecea et al 1998, Sakurai et al 1998). For detailed discussion of OX signaling pathways, the reader is referred to several excellent reviews (Baimel et al 2015, James et al 2017, Schone and Burdakov 2017, Sharf et al 2010, Tsujino and Sakurai 2009). Briefly, their projections are most highly concentrated within the limbic system. The heaviest efferent output of the OX neurons is to the locus coeruleus, but OX fibers also travel to various regions of the forebrain (nucleus accumbens, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, paraventricular and central medial thalamus, and amygdala) and hindbrain (ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra, nucleus of the solitary tract, periaqueductal gray, dorsal raphe and raphe magnus, and reticular nuclei) (Peyron et al 1998). The OX receptors have been identified within each of these regions (Marcus et al 2001, Trivedi et al 1998). Afferent input to OX neurons generally arises from the same regions that receive OX projections, including the forebrain (nucleus accumbens, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, amygdala, infralimbic cortex, cingulate cortex, and lateral septum), hindbrain (locus coeruleus, ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra, periaqueductal gray, and dorsal raphe), and the hypothalamus itself (medial preoptic area, suprachiasmatic nucleus, anterior hypothalamus, ventromedial hypothalamus, supramammillary nucleus, and posterior hypothalamus) (Yoshida et al 2006). Together, these connections position OX as an important component of the brain’s limbic, motivation network.

3. Role of orexin/hypocretin in normal eating

Early research on OX and food intake focused on its participation in the homeostatic regulation of feeding, reporting that OX neurons are activated under conditions of deprivation and promote food intake to maintain nutritional homeostasis (eg. (Cai et al 2001, Dube et al 1999, Yamanaka et al 2003)). While not explicitly examining seeking or foraging behavior, this early work, and the more recent research that has emerged from it (eg. (Inutsuka et al 2014)), nevertheless clearly demonstrates that OX promotes food intake in cases when an organism requires nutrition.

3.1. Effects of energy status on endogenous orexin/hypocretin

Studies in rodents provide strong evidence that OX neurons are activated under conditions of food deprivation or food anticipation (when animals are presumably seeking food), and that this OX excitation is diminished once animals obtain food. Gene expression and peptide levels of OX have been observed to be elevated after a 48 or 72 hour fast (Cai et al 1999, Fujiki et al 2001, Sakurai et al 1998). Similarly, under a restricted feeding paradigm, OX neurons are found to be more active during the food-anticipatory period or at the onset of food presentation (Johnstone et al 2006, Mieda et al 2004), suggesting that the neurons fire when an animal expects to obtain food. This could be triggered by a drop in glucose levels, as OX activity as measured by whole-cell patch-clamp recording is stimulated by a reduction in glucose (Yamanaka et al 2003) and OX gene expression, hypothalamic peptide levels, and activation as measured by co-labeling with the immediate early gene c-Fos are all upregulated by insulin- or 2-deoxyglucose-induced hypoglycemia (Bayer et al 2000, Briski and Sylvester 2001, Cai et al 2001, Griffon d et al 1999, Moriguchi et al 1999). Whereas excessively high levels of glucose do not appear to affect OX gene expression (Griffond et al 1999), refeeding or, in vivo, a physiological rise in levels of glucose serves to normalize the elevation in OX peptide levels and neuron activity (Burdakov et al 2005, Cai et al 2001, Yamanaka et al 2003). Similarly, the increase in OX levels and activity during food anticipation could be triggered by a drop in levels of leptin or a rise in ghrelin (Beck and Richy 1999, Liu et al 2017, Yamanaka et al 2003). Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that the actual ingestion of food is not necessary to reduce the fasting-induced activation of OX. Specifically, OX cell activity, monitored with fiber photometry, was found in mice to be rapidly depressed following the onset of physical contact with food, regardless of its nutritional content or texture (Gonzalez et al 2016). Together, these results suggest that OX neurons are excited and transcribe the neuropeptide when glucose and leptin levels are low and ghrelin levels are high, such as during food restriction or deprivation, but that this action is terminated once food consumption is initiated, even prior to a postprandial change in glucose and feeding-related hormones.

3.2. Effects of orexin/hypocretin on normal food intake

Despite a lack of OX cell activation during the actual consumption of food (see Section 3.1), OX activity has been demonstrated across multiple studies to result in increased feeding (Fig 1). General activation of the OX neuron population in mice, through chemogenetics, has been reported to stimulate intake of standard chow (Inutsuka et al 2014) and intranasal application of OX-A in rats induces a similar effect (Dhuria et al 2016). Conversely, postnatal, genetic ablation of OX neurons in mice leads them to reduce their chow intake during the dark phase of the light cycle, when mice are commonly most active and engage in the majority of their food intake (Hara et al 2001). Curiously, however, ablation of OX neurons in adult mice leads them to consume more chow than controls during the dark phase (Gonzalez et al 2016). This suggests that developmental stage at the time of OX cell loss may be an important determinant of behavioral outcome. While these studies collectively indicate that feeding is affected by OX neurons, it is important to note that the OX cells transcribe several other neurochemicals that may also be affected by OX neuron manipulation. Thus, more direct examination of OX and its receptors is required to confirm the involvement of this specific neuropeptide in food intake.

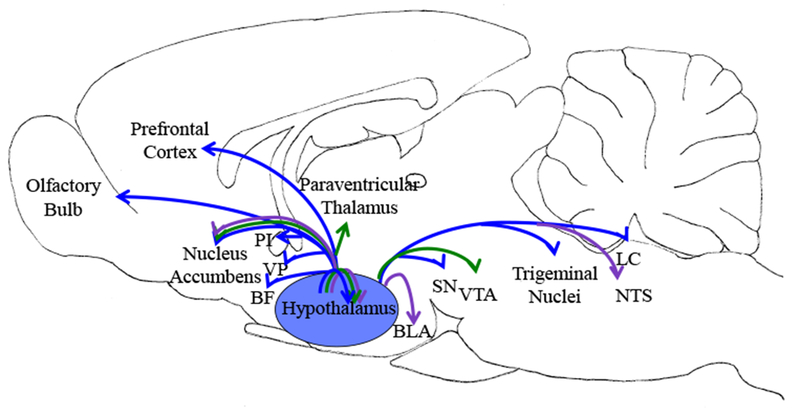

Fig 1.

Orexin/hypocretin release throughout the brain promotes normal food intake (purple arrows), dysregulated eating (green arrows), and foraging behavior (blue arrows). Schematic image represents brain regions shown in published literature to be involved in these behaviors. Abbreviations: BF, basal forebrain; BLA, basolateral amygdala; LC, locus coeruleus; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; PI, posterior insula; SN, substantia nigra; VP, ventral pallidum; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Microinjection experiments with OX agonists and receptor antagonists also support a role for OX in the promotion of feeding, and they indicate that this primarily occurs via OX-A and the OX1R and through the same regions of the hypothalamus where OX is transcribed. The OX-A peptide has been found to stimulate chow intake in rats when injected into the perifornical, lateral, dorsomedial, and paraventricular regions of the hypothalamus (Dube et al 1999, Kotz et al 2002, Sweet et al 1999) and in the medial but not ventrolateral preoptic area (Mavanji et al 2015, Sarihi et al 2015). Outside of the hypothalamus, OX-A also stimulates food intake in rats after injection into the nucleus accumbens shell (Mayannavar et al 2014, Thorpe and Kotz 2005) but not in the central amygdala or ventral tegmental area (Dube et al 1999, Sweet et al 1999). In contrast to OX-A, OX-B appears to have minimal effects on feeding (Dube et al 1999, Lubkin and Stricker-Krongrad 1998, Sweet et al 1999), although a recent study in rats found that it stimulated chow intake following injection into the basolateral amygdala (Rashmi et al 2015). While OX-A binds to both receptors, OX-B binds primarily to the OX2R, so these studies with OX peptides suggest that the majority of the feeding effects likely occur through the OX1R. Indeed, the OX1R antagonist, SB-334867, has been shown in several studies to inhibit chow feeding after systemic injection at a relatively high dose of 30 mg/kg (Haynes et al 2000, Ishii et al 2005) and after local microinjection into the nucleus accumbens or nucleus of the solitary tract (Kay et al 2014, Mayannavar et al 2016). Although most studies using antagonists have targeted the OX1R, one study has targeted the OX2R, using TCS-OX2-29, and found that an OX2R antagonist could also reduce food intake, this time when injected into the basolateral amygdala (Rashmi et al 2015). While more research remains to be conducted on the OX2R, the overall evidence strongly supports a role for OX, particularly the OX1R within the hypothalamus and also nucleus accumbens shell, in promoting normal food intake.

4. Role of orexin/hypocretin in dysregulated eating

Given its ability to promote the intake of standard chow, it is perhaps not surprising that OX also stimulates excessive and even binge-like eating of palatable food. In foraging animals, the consumption of energy-dense foods allows for more efficient fulfillment of energy demands, thus freeing up resources for other activities. Moreover, foraging animals may need to find food and eat it quickly, in order to avoid predation (Kavaliers and Choleris 2001). The overconsumption of palatable food can facilitate energy storage in preparation for future scarcity. In humans, foraging behavior can be observed in the form of binge eating (Brunstrom and Cheon 2018), characterized by obtaining and consuming an excessive amount of food in a discrete period of time regardless of physical hunger (American_Psychological_Association 2013), and most commonly involving the consumption of palatable foods, rich in fat and sugar (National_Eating_Disorders_Association 2016). The behavior is now considered to be a symptom of several eating disorders, most notably binge-eating disorder, which is currently the most common eating disorder in the United States (National_Eating_Disorders_Association 2016).

In rodents, a number of relatively recent studies has examined the role of OX in binge-like eating. In these studies, animals are given very limited access (typically, 30 minutes to 2 hours per session) to foods rich in fat and/or sugar, often with no restriction in access to normal chow, or they are provided with longer (typically, 12 hours per day), intermittent access to these palatable foods (Corwin et al 2011). Under these binging paradigms, intake escalates across sessions, particularly in the first hour of access, such that it resembles human binge eating (Corwin et al 2011). The results of this research show that OX shares a similar relationship with binge-like palatable food intake as it does with normal chow intake (Castro et al 2016, Thorpe and Kotz 2005), but with some important differences. Notably, levels of OX are higher following binge-like eating (eg. (Olszewski et al 2009)). In addition, this peptide can promote both the eating of and willingness to work for palatable food (eg. (Choi et al 2010, Valdivia et al 2015)), effectively energizing seeking for energy-dense food. Critically, while OX receptor antagonists can reduce eating and the energy put forth to obtain palatable food, they are able to do so at doses lower than those required to inhibit homeostatic eating (eg. (Alcaraz-Iborra et al 2014 Vickers et al 2015)), indicating that an OX-based pharmacotherapy could be administered at a dose that affected only palatable and not normal food intake.

4.1. Relationship of palatable food intake with endogenous orexin/hypocretin

Levels and activity of OX neurons relative to excessive palatable food intake generally mirror those found relative to standard chow, except that they are higher after palatable food than after chow intake. As with anticipation of scheduled access to chow, OX neurons during anticipation of chocolate show higher c-Fos co-labeling, and this occurs to the same degree as during anticipation of access to a daily chow meal (Choi et al 2010). Similarly, just as OX cell activity is inhibited after contact with food (Gonzalez et al 2016), OX gene expression and peptide levels are unchanged or reduced immediately following the consumption of palatable foods, such as sucrose or saccharin solutions (Alcaraz-Iborra et al 2014, Furudono et al 2006, Olney et al 2015). Interestingly, however, OX gene expression and c-Fos co-labeling are significantly increased between 30 minutes and 2 hours following the cessation of a palatable food binge, as observed with saccharin and fructose solutions compared to water, as well as with sucrose-sweetened and sweet-fat chow compared to standard chow (Furudono et al 2006, Olszewski et al 2009, Rorabaugh et al 2014, Valdivia et al 2015, Valdivia et al 2014). Importantly, since this occurs at a level higher than after intake of standard laboratory chow (Olszewski et al 2009, Valdivia et al 2015 Valdivia et al 2014), seeking after the intake of palatable food might occur again sooner than after consumption of a more balanced meal. Together, these results support the idea that endogenous OX plays a particularly strong role in promoting palatable food intake.

4.2. Effects of orexin/hypocretin on excessive and binge-like palatable food intake

Similar to its effects on the intake of standard chow, OX also promotes hedonic and binge-like intake of palatable food, which may reflect a strong foraging drive. Notably, while both types of eating involve the hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens shell, hedonic and binge-like intake involve multiple additional limbic brain regions (Fig 1). Thus, in rats, OX-A has been found when microinjected into the nucleus accumbens shell to stimulate binge-like intake of sweet chocolate (Castro et al 2016), into the ventral tegmental area to stimulate hedonic intake of sucrose or high-fat diet (Terrill et al 2016), and into the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus to stimulate binge-like intake of sucrose (Barson et al 2015). Conversely, microinjection into the ventral tegmental area of the OX1R antagonist, SB-334867, suppresses drinking of a sucrose solution (Terrill et al 2016) and knockdown of the OX1R in the paraventricular thalamus attenuates hedonic intake of a high-fat diet (Choi et al 2012).

Evidence using systemic manipulation of the OX receptors largely supports a role for the OX1R in binge-like eating. Few studies have examined the ability of an OX2R antagonist to inhibit palatable food intake, with one using systemic LSN242100 in mice and finding that it reduces binge-like sucrose drinking and others in male mice and female rats using GSK1059865 or JNJ-10397049, respectively, and reporting no effect (Anderson et al 2014, Lopez et al 2016, Piccoli et al 2012). In contrast, a large body of research utilizing systemic injections supports a role for the OX1R in palatable food consumption, with most studies using SB-334867 and reporting that it reduces binge-like intake in both rats and mice, testing with sweet-fat pellets, milk chocolate, sucrose, fructose, and saccharin (Alcaraz-Iborra et al 2014, Olney et al 2015, Rorabaugh et al 2014, Valdivia et al 2015, Vickers et al 2015). Other research with GSK1059865 further supports this conclusion, showing that this OX1R antagonist selectively reduces binge eating of a sweet-fat diet in female rats (Piccoli et al 2012). Critical to pharmacotherapeutic implementation, the ability of SB-334867 to inhibit binge-like palatable food intake consistently occurs at doses lower than that necessary for chow feeding (as low as 3 mg/kg, compared to 30 mg/kg). While there are several possible explanations for this phenomenon, it may be that binge eating is driven by a less diverse array of neurochemicals than homeostatic feeding, which could allow the former behavior to be more easily inhibited by the antagonism of a single neuropeptide signal. Alternatively, the known influence of the higher dose of SB-334867 on other neurochemicals (Gotter et al 2012) could be necessary for its effect on chow intake. Regardless, the results indicate that the OX1R could be targeted for pharmacotherapy to treat binge eating, and that this could be accomplished in a way that left undisturbed behaviors such as homeostatic eating which are necessary for survival.

Research involving operant behavior begins to elucidate a possible mechanism for the ability of OX to promote binge-like palatable food intake. Specifically, OX can increase the effort put forth to obtain this type of food. Under a fixed ratio 1 or fixed ratio 3 schedule of reinforcement (requiring 1 or 3 correct responses to earn the reinforcer), systemic SB-334867 in rats, at a dose as low as 5 mg/kg, has been shown to reduce lever-pressing for sucrose, saccharin, and high-fat diet (Cason and Aston-Jones 2013a, Cason and Aston-Jones 2014, Jupp et al 2011, Nair et al 2008). In contrast, the OX2R antagonists, JNJ-10397049 and TCS-OX2-29, appear to have no effect in rats on fixed ratio responding for sucrose or saccharin (Brown et al 2013, Shoblock et al 2011). More importantly, in a progressive ratio task (which successively increases the number of operant responses required to earn the reinforcer, with the breakpoint being the requirement at which responding ceases), OX increases willingness to work for palatable food and SB-334867 can decrease it. Specifically, OX-A in rats increases breakpoint for sucrose when injected into the lateral hypothalamic area or adjacent third ventricle (Choi et al 2010, Thorpe et al 2005), although not in the ventral tegmental area (Terrill et al 2016). Conversely, while knockdown of the OX1R in the paraventricular thalamus of rats does not affect breakpoint for a high-fat diet (Choi et al 2012), systemic SB-334867 reduces breakpoint for fat or sucrose, at doses of 10 mg/kg or higher (Borgland et al 2009, Cason and Aston-Jones 2013b, Choi et al 2010, Espana et al 2010, Jupp et al 2011). These findings with operant behavior strengthen the idea that the OX1R can be targeted to treat binge eating and, further, suggest that it would do so by reducing the effort that individuals are willing to expend to engage in this behavior, as would be required during foraging.

In contrast to fixed and progressive ratio responding for available palatable food, the reinstatement of extinguished operant responding for palatable food, with a few exceptions, does not appear to be affected by OX. Seeking for high-fat food can be induced by intracerebroventricular microinjection of OX-A (Nair et al 2008) and, in male rats, cue-induced reinstatement of sucrose- or saccharin-seeking can be reduced by systemic injection of a high dose (30 mg/kg) of SB-334867 (Cason and Aston-Jones 2013a, Cason and Aston-Jones 2013b). On the other hand, this same behavior of cue-induced sucrose-seeking is not affected by the same dose of SB-334867 in female rats (Cason and Aston-Jones 2014) and cue-induced reinstatement of seeking for sweetened condensed milk or the sweet solution, SuperSac, is not altered in male rats using lower doses of this drug (Martin-Fardon and Weiss 2014a, Martin-Fardon and Weiss 2014b). Moreover, the dual OX antagonist, TCS 1102, does not affect cue-induced seeking for sweet-fat pellets (Khoo et al 2017). This lack of effect of OX antagonists on cue-induced seeking behavior has similarly been observed under other paradigms of reinstatement. For example, SB-334867, at doses as high as 20 mg/kg, has no effect on reinstatement of high-fat seeking when it is induced by OX-A, pellet-priming, or the pharmacological stressor, yohimbine (Nair et al 2008). Thus, while a high dose of an OX receptor antagonist may be capable of preventing reinstatement of palatable food seeking, the majority of studies indicate that OX is likely not a significant factor in driving this behavior, where work will no longer result in a food reward.

5. The case for foraging

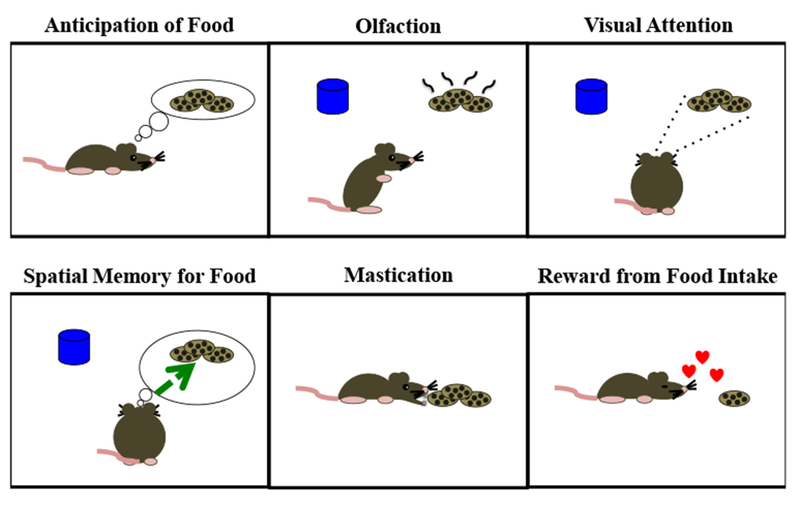

Rather than promoting palatable food seeking under conditions of discontinued access (as in the reinstatement of extinguished seeking), OX appears to have a strong relationship with palatable food seeking under conditions of limited access. This is consistent with a role for OX in foraging behavior. Successful foraging involves the coordination of a number of complex behaviors, including not only anticipation and seeking of available energy-dense foods, but also olfaction and visual attention to identify the foods as well as threats, efficient consumption of the food to minimize the chance of encountering predators or competitors, and memory for locations where preferred food has previously been available. A body of literature shows that OX, acting through various brain regions (Fig 1), is involved in promoting all of these phenomena (Fig 2) (eg. (Aitta-Aho et al 2016, Ferry and Duchamp-Viret 2014, Tsuji et al 2011, Zajo et al 2016)). Thus, OX could stimulate binge eating of palatable food due to its role in foraging behavior.

Fig 2.

Orexin/hypocretin promotes multiple aspects of foraging behavior. This includes anticipation and seeking of available energy-dense foods, olfaction and visual attention to identify food, memory for locations where preferred food has previously been available, rapid consumption of food, and reward from intake of palatable food.

5.1. Orexin/hypocretin and seeking of palatable food

A relationship for OX with seeking behavior can be observed in its strong association with anticipation of food during periods of limited access. This may reflect a role for OX in foraging behavior, which is necessary when food is scarce but still available. As reviewed above (Sections 3.1 and 4.1), studies using the immediate early gene c-Fos show that OX neurons are activated during the food-anticipatory period of restricted feeding for both normal chow and chocolate (Choi et al 2010, Mieda et al 2004). More recently, a study using juxtacellular recording reported that OX neurons discharge at high rates during a tone that predicts the subsequent availability of sucrose (Hassani et al 2016). In this experiment, rats were presented with a stimulus tone and if, following this tone, they licked within a predefined time period, they were rewarded with the oral delivery of sucrose. Interestingly, while the discharge of OX neurons was stimulated by the tone, the firing continued at an elevated rate until the onset of licking (Hassani et al 2016), mirroring the finding (Section 3.1) that OX cell firing ceases once food is obtained (Gonzalez et al 2016). This indicates that OX neurons are involved not just in awareness that food is available, but also in promoting the behavior required to obtain it. In support of a causal role for OX neurons in food seeking, genetically OX-neuron ablated mice show reduced food-anticipatory wakefulness and locomotor activity under restricted feeding conditions (Akiyama et al 2004, Mieda et al 2004), again suggesting that OX may be necessary for the performance of seeking-related behavior prior to obtaining food. Thus, when the expectation of food access has not been extinguished (as occurs in experiments involving reinstatement), OX neurons appear to be activated during the period of food anticipation and themselves drive the behaviors that reflect it.

It is worth noting that, in addition to waking and sympathetic activation (Barson and Leibowitz 2017, Messina et al 2014), OX has also been found to promote spontaneous physical activity (SPA), defined as ambulatory activity outside of formal exercise, although SPA is believed not to be associated with food seeking. Chemogenetic activation of a restricted population of OX neurons leads mice to increase their SPA, resulting in a greater number of trips to their food hopper (Zink et al 2018). Investigating specific brain regions through which this effect might occur, OX-A has been observed to stimulate SPA in rats after microinjection in the lateral and paraventricular hypothalamus (Kiwaki et al 2004, Kotz et al 2006), ventrolateral preoptic area (Mavanji et al 2015), nucleus accumbens shell (Thorpe and Kotz 2005), substantia nigra (Kotz et al 2006), and locus coeruleus (Teske et al 2013). Notably, microinjection of OX in a few of these regions, specifically the lateral hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens shell, also stimulates both homeostatic chow intake and binge-like intake of palatable food (see Sections 3.2 and 4.2). Thus, even if not specifically directed at obtaining food, OX robustly energizes locomotor activity.

5.2. Orexin/hypocretin and olfaction

A heightened sense of smell can be beneficial in identifying both sources of food and threats, and OX, at least in the rat, is active in the olfactory bulb and affects olfaction and performance in olfactory-based tasks. The presence of OX-A and OX-B terminals (Shibata et al 2008) and OX receptors (Caillol et al 2003), as well as OX-A-induced alterations in firing (Apelbaum et al 2005, Hardy et al 2005) has been observed in the rat olfactory bulb mitral-tufted cells, the relay neurons between the periphery and brain. Notably, the activity of OX at these cells may reflect nutritional status. Fasting increases both sniffing behavior and olfactory bulb c-Fos expression, and intracerebroventricular microinjection of OX-A in sated rats similarly increases olfactory bulb c-Fos while, conversely, a dual OX receptor antagonist in fasted rats decreases olfactory bulb c-Fos and sniffing (Prud’homme et al 2009). This may reflect an ability of OX to alter olfactory sensitivity, as systemic injection of SB-334867 in rats increases approach to a cat odor, which normally induces unconditioned avoidance (Staples and Cornish 2014, Vanderhaven et al 2015). The OX-induced increase in olfactory sensitivity can result in enhanced olfactory-based learning. For example, in an olfactory discrimination task, where rats are required to dig into scented cups of sand to obtain Froot Loop® rewards, injection of OX-A into the basal forebrain facilitates both acquisition and reversal performance, while SB-334867 impairs them (Piantadosi et al 2015). Similarly, in a test of conditioned olfactory aversion with odorized water, OX-A injected into the lateral ventricle decreases subsequent intake of water scented with the odorant, even when at far lower concentrations than used for conditioning (Ferry and Duchamp-Viret 2014, Julliard et al 2007). All together, the research suggests that OX affects olfactory sensitivity as well as olfactory-based learning, and that this ability may be enhanced during times of limited food access, when detecting food should be a priority.

5.3. Orexin/hypocretin and visual attention

As with olfaction, visual attention can also assist with the identification of food and threats for foraging animals. Thus, it is interesting to note that OX also enhances visual attention. For example, in a self-paced rat visuospatial sustained and divided attention task for a food reward, injection of OX-A into the prefrontal cortex improves accuracy under high attentional demand (Lambe et al 2005). Similarly, in a two-lever sustained attention task in rats, with water as the reinforcer, OX-A injection into the basal forebrain attenuates distractor-induced decreases in attentional performance (Zajo et al 2016), whereas SB-334867 in this same brain region decreases overall accuracy in this same task (Boschen et al 2009). Thus, OX appears to enhance sustained attention, or vigilance, which is necessary for successful foraging.

5.4. Orexin/hypocretin and spatial memory for food

Memory for the location(s) where preferred food has been available can expedite the procurement of food in foraging animals and OX appears to enhance this phenomenon as well. Using chemogenetics, one study in mice found that increasing OX neuron activity improved short-term memory for a novel spatial location, assessed through a delayed spontaneous alternation T-maze test for a food reward (Aitta-Aho et al 2016). Conversely, another study found that OX knockout mice were less successful than control mice in this same task (Dang et al 2018). Moreover, this effect of OX on memory appears to be specific for spatial memory, as OX neuron activation did not affect performance in a non-food baited object recognition task (Aitta-Aho et al 2016). Thus, OX neurons may support memory during foraging behavior, which would ultimately facilitate the acquisition of food.

5.5. Orexin/hypocretin and mastication

Once animals obtain food, it can be advantageous for them to consume it rapidly, particularly if they need to protect their food against conspecifics or protect themselves against predation (Whishaw et al 1992). Both OX-A and OX-B facilitate mastication, leading animals to open their jaws wider and chew faster. Notably, OX-B terminals and both OX1R and OX2R have been identified in several nuclei of the rat pons, including the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus and trigeminal motor nucleus, which contain the sensory and motor neurons involved in the jaw muscles used in mastication (Greco and Shiromani 2001, Zhang and Luo 2002). Intracerebroventricular microinjection of OX-A leads rats to open their mouth quickly and widely and then powerfully crush the increased amount of food in their mouth (Tsuji et al 2011). These results demonstrate that OX can aid foraging animals in consuming food at a rapid pace.

5.6. Orexin/hypocretin and reward from palatable food intake

Following the consumption of palatable food, OX also appears to enhance its rewarding effects, possibly as a means of reinforcing foraging behavior. For example, in circumscribed regions of the rat nucleus accumbens shell, ventral pallidum, orbitofrontal cortex, and posterior insula, microinjection of OX-A enhances the hedonic impact, or “liking”, of a low concentration of sucrose, as measured by orofacial reaction (Castro and Berridge 2017, Castro et al 2016, Ho and Berridge 2013). Moreover, preference for a high-fat-paired chamber in a conditioned place preference test, another measure of liking, can be blocked by pretreatment with the OX1R antagonist, SB-334867, administered into the fourth ventricle (Kay et al 2014). These studies together suggest that OX is endogenously active at its receptors following the ingestion of palatable food. Given the findings that OX neurons cease firing once an animal contacts food (Section 3.1) (Gonzalez et al 2016), but that OX receptor binding can affect post-synaptic neurons for many minutes (Scammell and Winrow 2011), it may be that OX remains active in the brain during the early stages of food consumption. This could serve to enhance the hedonic impact of ingestion and thus increase the likelihood of seeking out that same food in the future.

6. Clinical relevance?

With the animal literature clearly supporting a role for OX in binge-like eating, it is interesting that evidence from clinical studies also strongly supports a role for OX in binge eating, albeit in the opposite direction than predicted. Specifically, individuals with OX-deficient narcolepsy score significantly higher than healthy matched controls on a binge eating scale (Dimitrova et al 2011) and they more frequently show features of bulimia nervosa (Chabas et al 2007). Moreover, when given unrestricted access to snacks in a laboratory, they consume almost four times more calories than controls (van Holst et al 2016). While these results are surprisingly opposite to those observed in animals, they may be due to the timing of the OX cell loss. The onset of narcolepsy most commonly occurs during late adolescence or young adulthood (Overeem et al 2001). Recall that ablation of OX neurons in mice also leads to increased food intake when it occurs in adulthood (Gonzalez et al 2016) whereas it leads to reduced intake when it occurs postnatally (Hara et al 2001) (see Section 3.2). Thus, while interesting in their own right, the results from narcolepsy studies may not represent normal OX system physiology. Thus, future research should investigate the role of OX in binge eating in non-narcoleptic individuals.

In contrast to binge eating, anorexia nervosa may not be related to OX. While one study reported significantly lower OX-A plasma levels in patients with the restrictive type of anorexia nervosa compared to healthy matched controls (Janas-Kozik et al 2011), another reported higher plasma levels (Bronsky et al 2011) while a third found no difference (Sauchelli et al 2016). Although this does not rule out a role for OX in disorders involving voluntary food restriction, the evidence at this time does not strongly support it.

7. Conclusions

Twenty years after its discovery, OX is now firmly established as promoting both normal, homeostatic eating as well as dysregulated, binge-like eating. This occurs predominantly through the OX1R in the hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens, but it may also involve other limbic regions as well as the OX2R. Interestingly, while OX stimulates the consumption of food, it also robustly stimulates appetitive behavior, or seeking, for food. The hypothesis here that the fundamental, underlying role of OX in these food-related processes is the promotion of foraging behavior, which occurs in numerous species when resources are limited. While this behavior is expected ultimately to result in homeostatic regulation of energy levels, perhaps a better representation of food intake in foraging animals is the model of allostasis, which holds that physiological systems fluctuate to meet changing demands from external forces (McEwen and Stellar 1993). Thus, OX should promote the consumption of food to meet immediate physiological needs, but it could also promote the overconsumption of food to facilitate energy storage in defense against future food shortage. In an environment characterized by an abundance of energy-dense palatable food that can be obtained at low energy cost, this behavior could manifest as disorders such as binge-eating disorder. Importantly, in rodents, a reduction in dysregulated feeding can be achieved with a significantly lower degree of OX receptor blockade than is required for the inhibition of normal eating. This indicates that an OX-based pharmacotherapy, particularly one targeting the OX1R, could be titrated to a dose that selectively affects binge eating of palatable food, while leaving basic appetite undiminished. Assuming that this system is similar in humans with an intact OX physiology, a medication targeting this neuropeptide may be most effective for patients wishing to treat ongoing binge eating behavior, given the apparent role for OX in seeking but not relapse for food. This benefit from an OX medication on feeding would be distinct from its effects on drug use, where it may instead be most beneficial in preventing relapse. It is tempting to speculate that these differences relate to the necessity of feeding for survival, and to the evolutionary preparation for seasonal variations in the availability of specific foods. Ultimately, the animal literature provides significant evidence that OX should be considered as a target to effectively manage pathological feeding behavior. Importantly, this ability of OX to affect excessive eating of palatable food may be due to its fundamental, underlying role in promoting foraging behavior.

Highlights.

The primary evolutionary function of orexin may be to promote foraging

Orexin neurons are activated by food deprivation and stimulate homeostatic feeding

Orexin also enhances intake and working for binge-like palatable food intake

Orexin stimulates seeking and anticipatory behavior for palatable food

Orexin promotes olfaction, attention, spatial memory, and mastication of food

Acknowledgements

Declarations of interest: none. This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under Award Number R00AA021782. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. I thank Dr. Sarah Leibowitz at The Rockefeller University for her editorial feedback.

Abbreviations:

- OX

orexin/hypocretin

- OX1R

orexin 1 receptor

- OX2R

orexin 2 receptor

- OX-A

orexin-A

- OX-B

orexin-B

- SPA

spontaneous physical activity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aitta-Aho T, Pappa E, Burdakov D & Apergis-Schoute J. 2016. Cellular activation of hypothalamic hypocretin/orexin neurons facilitates short-term spatial memory in mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem 136: 183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M, Yuasa T, Hayasaka N, Horikawa K, Sakurai T & Shibata S. 2004. Reduced food anticipatory activity in genetically orexin (hypocretin) neuron-ablated mice. Eur J Neurosci 20: 3054–3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz-Iborra M, Carvajal F, Lerma-Cabrera JM, Valor LM & Cubero I. 2014. Binge-like consumption of caloric and non-caloric palatable substances in ad libitum-fed C57BL/6J mice: pharmacological and molecular evidence of orexin involvement. Behav Brain Res 272: 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard JS, Tizabi Y, Shaffery JP, Trouth CO & Manaye K. 2004. Stereological analysis of the hypothalamic hypocretin/orexin neurons in an animal model of depression. Neuropeptides 38: 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeneessier AS, Alzoghaibi M, BaHammam AA, Ibrahim MG, Olaish AH, Nashwan SZ & BaHammam AS. 2018. The effects of diurnal intermittent fasting on the wake-promoting neurotransmitter orexin-A. Ann Thorac Med 13: 48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American_Psychological_Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RI, Becker HC, Adams BL, Jesudason CD & Rorick-Kehn LM. 2014. Orexin-1 and orexin-2 receptor antagonists reduce ethanol self-administration in high-drinking rodent models. Front Neurosci 8: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelbaum AF, Perrut A & Chaput M. 2005. Orexin A effects on the olfactory bulb spontaneous activity and odor responsiveness in freely breathing rats. Regul Pept 129: 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer ZA, Findlay PA, Rhind SM, Mercer JG & Adam CL. 2002. Orexin gene expression and regulation by photoperiod in the sheep hypothalamus. Regul Pept 104: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baimel C, Bartlett SE, Chiou LC, Lawrence AJ, Muschamp JW, Patkar O, Tung LW & Borgland SL. 2015. Orexin/hypocretin role in reward: implications for opioid and other addictions. Br J Pharmacol 172: 334–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Ho HT & Leibowitz SF. 2015. Anterior thalamic paraventricular nucleus is involved in intermittent access ethanol drinking: role of orexin receptor 2. Addict Biol 20: 469–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR & Leibowitz SF. 2017. Orexin/hypocretin system: role in food and drug overconsumption. Int Rev Neurobiol 136: 199–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer L, Colard C, Nguyen NU, Risold PY, Fellmann D & Griffond B. 2000. Alteration of the expression of the hypocretin (orexin) gene by 2-deoxyglucose in the rat lateral hypothalamic area. Neuroreport 11: 531–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B & Richy S. 1999. Hypothalamic hypocretin/orexin and neuropeptide Y: divergent interaction with energy depletion and leptin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 258: 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasiak A, Siwiec M, Grabowiecka A, Blasiak T, Czerw A, Blasiak E, Kania A, Rajfur Z, Lewandowski MH & Gundlach AL. 2015. Excitatory orexinergic innervation of rat nucleus incertus--Implications for ascending arousal, motivation and feeding control. Neuropharmacology 99: 432–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Chang SJ, Bowers MS, Thompson JL, Vittoz N, Floresco SB, Chou J, Chen BT & Bonci A. 2009. Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. J Neurosci 29: 11215–11225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen KE, Fadel JR & Burk JA. 2009. Systemic and intrabasalis administration of the orexin-1 receptor antagonist, SB-334867, disrupts attentional performance in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206: 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briski KP & Sylvester PW. 2001. Hypothalamic orexin-A-immunpositive neurons express Fos in response to central glucopenia. Neuroreport 12: 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronsky J, Nedvidkova J, Krasnicanova H, Vesela M, Schmidtova J, Koutek J, Kellermayer R, Chada M, Kabelka Z, Hrdlicka M, Nevoral J & Prusa R. 2011. Changes of orexin A plasma levels in girls with anorexia nervosa during eight weeks of realimentation. Int J Eat Disord 44: 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RM, Khoo SY & Lawrence AJ. 2013. Central orexin (hypocretin) 2 receptor antagonism reduces ethanol self-administration, but not cue-conditioned ethanol-seeking, in ethanol-preferring rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16: 2067–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstrom JM & Cheon BK. 2018. Do humans still forage in an obesogenic environment? Mechanisms and implications for weight maintenance. Physiol Behav page 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdakov D, Gerasimenko O & Verkhratsky A. 2005. Physiological changes in glucose differentially modulate the excitability of hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone and orexin neurons in situ. J Neurosci 25: 2429–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai XJ, Evans ML, Lister CA, Leslie RA, Arch JR, Wilson S & Williams G. 2001. Hypoglycemia activates orexin neurons and selectively increases hypothalamic orexin-B levels: responses inhibited by feeding and possibly mediated by the nucleus of the solitary tract. Diabetes 50: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai XJ, Widdowson PS, Harrold J, Wilson S, Buckingham RE, Arch JR, Tadayyon M, Clapham JC, Wilding J & Williams G. 1999. Hypothalamic orexin expression: modulation by blood glucose and feeding. Diabetes 48: 2132–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillol M, Aioun J, Baly C, Persuy MA & Salesse R. 2003. Localization of orexins and their receptors in the rat olfactory system: possible modulation of olfactory perception by a neuropeptide synthetized centrally or locally. Brain Res 960: 48–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cason AM & Aston-Jones G. 2013a. Attenuation of saccharin-seeking in rats by orexin/hypocretin receptor 1 antagonist. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 228: 499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cason AM & Aston-Jones G. 2013b. Role of orexin/hypocretin in conditioned sucrose-seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 226: 155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cason AM & Aston-Jones G. 2014. Role of orexin/hypocretin in conditioned sucrose-seeking in female rats. Neuropharmacology 86: 97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro DC & Berridge KC. 2017. Opioid and orexin hedonic hotspots in rat orbitofrontal cortex and insula. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E9125–E9134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro DC, Terry RA & Berridge KC. 2016. Orexin in rostral hotspot of nucleus accumbens enhances sucrose ‘liking’ and intake but scopolamine in caudal shell shifts ‘liking’ toward ‘disgust’ and ‘fear’. Neuropsychopharmacology 41: 2101–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabas D, Foulon C, Gonzalez J, Nasr M, Lyon-Caen O, Wilier JC, Derenne JP & Arnulf I. 2007. Eating disorder and metabolism in narcoleptic patients. Sleep 30: 1267–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XY, Chen L & Du YF. 2017. Orexin-A increases the firing activity of hippocampal CAI neurons through orexin-1 receptors. J Neurosci Res 95: 1415–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DL, Davis JF, Fitzgerald ME & Benoit SC. 2010. The role of orexin-A in food motivation, reward-based feeding behavior and food-induced neuronal activation in rats. Neuroscience 167: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DL, Davis JF, Magrisso IJ, Fitzgerald ME, Lipton JW & Benoit SC. 2012. Orexin signaling in the paraventricular thalamic nucleus modulates mesolimbic dopamine and hedonic feeding in the rat. Neuroscience 210: 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin RL, Avena NM & Boggiano MM. 2011. Feeding and reward: perspectives from three rat models of binge eating. Physiol Behav 104: 87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang R, Chen Q, Song J, He C, Zhang J, Xia J & Hu Z. 2018. Orexin knockout mice exhibit impaired spatial working memory. Neurosci Lett 668: 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM & Sutcliffe JG. 1998. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhuria SV, Fine JM, Bingham D, Svitak AL, Burns RB, Baillargeon AM, Panter SS, Kazi AN, Frey WH 2nd & Hanson LR. 2016. Food consumption and activity levels increase in rats following intranasal hypocretin-1. Neurosci Lett 627: 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova A, Fronczek R, Van der Ploeg J, Scammell T, Gautam S, Pascual-Leone A & Lammers GJ. 2011. Reward-seeking behavior in human narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med 7: 293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube MG, Kalra SP & Kalra PS. 1999. Food intake elicited by central administration of orexins/hypocretins: identification of hypothalamic sites of action. Brain Res 842: 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana RA. 2012. Hypocretin/orexin involvement in reward and reinforcement. Vitam Horm 89: 185–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana RA, Oleson EB, Locke JL, Brookshire BR, Roberts DC & Jones SR. 2010. The hypocretin-orexin system regulates cocaine self-administration via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Eur J Neurosci 31: 336–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry B & Duchamp-Viret P. 2014. The orexin component of fasting triggers memory processes underlying conditioned food selection in the rat. Learn Mem 21: 185–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki N, Yoshida Y, Ripley B, Honda K, Mignot E & Nishino S. 2001. Changes in CSF hypocretin-1 (orexin A) levels in rats across 24 hours and in response to food deprivation. Neuroreport 12: 993–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furudono Y, Ando C, Yamamoto C, Kobashi M & Yamamoto T. 2006. Involvement of specific orexigenic neuropeptides in sweetener-induced overconsumption in rats. Behav Brain Res 175: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HR, Zhuang QX, Zhang YX, Chen ZP, Li B, Zhang XY, Zhong YT, Wang JJ & Zhu JN. 2017. Orexin directly enhances the excitability of globus pallidus internus neurons in rat by co-activating OX1 and OX2 receptors. Neurosci Bull 33: 365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JA, Jensen LT, Iordanidou P, Strom M, Fugger L & Burdakov D. 2016. Inhibitory interplay between orexin neurons and eating. Curr Biol 26: 2486–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotter AL, Webber AL, Coleman PJ, Renger JJ & Winrow CJ. 2012. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVI. Orexin receptor function, nomenclature and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 64: 389–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco MA & Shiromani PJ. 2001. Hypocretin receptor protein and mRNA expression in the dorsolateral pons of rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 88: 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffond B, Risold PY, Jacquemard C, Colard C & Fellmann D. 1999. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia increases preprohypocretin (orexin) mRNA in the rat lateral hypothalamic area. Neurosci Lett 262: 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M & Sakurai T. 2001. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 30: 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy AB, Aioun J, Baly C, Julliard KA, Caillol M, Salesse R & Duchamp-Viret P. 2005. Orexin A modulates mitral cell activity in the rat olfactory bulb: patch-clamp study on slices and immunocytochemical localization of orexin receptors. Endocrinology 146: 4042–4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassani OK, Krause MR, Mainville L, Cordova CA & Jones BE. 2016. Orexin neurons respond differentially to auditory cues associated with appetitive versus aversive outcomes. J Neurosci 36: 1747–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes AC, Jackson B, Chapman H, Tadayyon M, Johns A, Porter RA & Arch JR. 2000. A selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist reduces food consumption in male and female rats. Regul Pept 96: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CY & Berridge KC. 2013. An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic ‘liking’ for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology 38: 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath TL, Diano S & van den Pol AN. 1999. Synaptic interaction between hypocretin (orexin) and neuropeptide Y cells in the rodent and primate hypothalamus: a novel circuit implicated in metabolic and endocrine regulations. J Neurosci 19: 1072–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesa G, van den Pol AN & Finger TE. 2005. Differential distribution of hypocretin (orexin) and melanin-concentrating hormone in the goldfish brain. J Comp Neurol 488: 476–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inutsuka A, Inui A, Tabuchi S, Tsunematsu T, Lazarus M & Yamanaka A. 2014. Concurrent and robust regulation of feeding behaviors and metabolism by orexin neurons. Neuropharmacology 85: 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Blundell JE, Halford JC, Upton N, Porter R, Johns A, Jeffrey P, Summerfield S & Rodgers RJ. 2005. Anorexia and weight loss in male rats 24 h following single dose treatment with orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867. Behav Brain Res 157: 331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Mahler SV, Moorman DE & Aston-Jones G. 2017. A decade of orexin/hypocretin and addiction: where are we now? Curr Top Behav Neurosci 33: 247–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas-Kozik M, Stachowicz M, Krupka-Matuszczyk I, Szymszal J, Krysta K, Janas A & Rybakowski JK. 2011. Plasma levels of leptin and orexin A in the restrictive type of anorexia nervosa. Regul Pept 168: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone LE, Fong TM & Leng G. 2006. Neuronal activation in the hypothalamus and brainstem during feeding in rats. Cell Metab 4: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julliard AK, Chaput MA, Apelbaum A, Aime P, Mahfouz M & Duchamp-Viret P. 2007. Changes in rat olfactory detection performance induced by orexin and leptin mimicking fasting and satiation. Behav Brain Res 183: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B, Krivdic B, Krstew E & Lawrence AJ. 2011. The orexin(1) receptor antagonist SB-334867 dissociates the motivational properties of alcohol and sucrose in rats. Brain Res 1391: 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslin J, Nystedt JM, Ostergard M, Peitsaro N & Panula P. 2004. The orexin/hypocretin system in zebrafish is connected to the aminergic and cholinergic systems. J Neurosci 24: 2678–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaliers M & Choleris E. 2001. Antipredator responses and defensive behavior: ecological and ethological approaches for the neurosciences. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25: 577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay K, Parise EM, Lilly N & Williams DL. 2014. Hindbrain orexin 1 receptors influence palatable food intake, operant responding for food, and food-conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231: 419–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler BA, Stanley EM, Frederick-Duus D & Fadel J. 2011. Age-related loss of orexin/hypocretin neurons. Neuroscience 178: 82–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo SY, Clemens KJ & McNally GP. 2017. Palatable food self-administration and reinstatement are not affected by dual orexin receptor antagonism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry page 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwaki K, Kotz CM, Wang C, Lanningham-Foster L & Levine JA. 2004. Orexin A (hypocretin 1) injected into hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and spontaneous physical activity in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 286: E551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz CM, Teske JA, Levine JA & Wang C. 2002. Feeding and activity induced by orexin A in the lateral hypothalamus in rats. Regul Pept 104: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz CM, Wang C, Teske JA, Thorpe AJ, Novak CM, Kiwaki K & Levine JA. 2006. Orexin A mediation of time spent moving in rats: neural mechanisms. Neuroscience 142: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe EK, Olausson P, Horst NK, Taylor JR & Aghajanian GK. 2005. Hypocretin and nicotine excite the same thalamocortical synapses in prefrontal cortex: correlation with improved attention in rat. J Neurosci 25: 5225–5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer CJ & Krieg JC. 2004. Sleep in eating disorders. Sleep Med Rev 8: 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JJ, Bello NT & Pang ZP. 2017. Presynaptic regulation of leptin in a defined lateral hypothalamus-ventral tegmental area neurocircuitry depends on energy state. J Neurosci 37: 11854–11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Moorman DE, Aston-Jones G & Becker HC. 2016. The highly selective orexin/hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist GSK1059865 potently reduces ethanol drinking in ethanol dependent mice. Brain Res 1636: 74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubkin M & Stricker-Krongrad A. 1998. Independent feeding and metabolic actions of orexins in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 253: 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magga J, Bart G, Oker-Blom C, Kukkonen JP, Akerman KE & Nasman J. 2006. Agonist potency differentiates G protein activation and Ca2+ signalling by the orexin receptor type 1. Biochem Pharmacol 71: 827–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler SV, Moorman DE, Smith RJ, James MH & Aston-Jones G 2014. Motivational activation: a unifying hypothesis of orexin/hypocretin function. Nat Neurosci 17: 1298–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M & Elmquist JK. 2001. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 435: 6–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R & Weiss F. 2014a. Blockade of hypocretin receptor-1 preferentially prevents cocaine seeking: comparison with natural reward seeking. Neuroreport 25: 485–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R & Weiss F. 2014b. N-(2-methyl-6-benzoxazolyl)-N’−1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl urea (SB334867), a hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist, preferentially prevents ethanol seeking: comparison with natural reward seeking. Addict Biol 19: 233–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavanji V, Perez-Leighton CE, Kotz CM, Billington CJ, Parthasarathy S, Sinton CM & Teske JA. 2015. Promotion of wakefulness and energy expenditure by orexin-A in the ventrolateral preoptic area. Sleep 38: 1361–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayannavar S, Rashmi KS, Rao YD, Yadav S & Ganaraja B. 2014. Effect of orexin-A infusion in to the nucleus accumbens on consummatory behaviour and alcohol preference in male wistar rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 58: 319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayannavar S, Rashmi KS, Rao YD, Yadav S & Ganaraja B. 2016. Effect of orexin A antagonist (SB-334867) infusion into the nucleus accumbens on consummatory behavior and alcohol preference in wistar rats. Indian J Pharmacol 48: 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS & Stellar E. 1993. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med 153: 2093–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina G, Dalia C, Tafuri D, Monda V, Palmieri F, Dato A, Russo A, De Blasio S, Messina A, De Luca V, Chieffi S & Monda M. 2014. Orexin-A controls sympathetic activity and eating behavior. Front Psychol 5: 997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M 2017. The roles of orexins in sleep/wake regulation. Neurosci Res 118: 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M, Williams SC, Sinton CM, Richardson JA, Sakurai T & Yanagisawa M. 2004. Orexin neurons function in an efferent pathway of a food-entrainable circadian oscillator in eliciting food-anticipatory activity and wakefulness. J Neurosci 24: 10493–10501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modirrousta M, Mainville L & Jones BE. 2005. Orexin and MCH neurons express c-Fos differently after sleep deprivation vs. recovery and bear different adrenergic receptors. Eur J Neurosci 21: 2807–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman DE. 2018. The hypocretin/orexin system as a target for excessive motivation in alcohol use disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 235: 1663–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T, Sakurai T, Nambu T, Yanagisawa M & Goto K. 1999. Neurons containing orexin in the lateral hypothalamic area of the adult rat brain are activated by insulin-induced acute hypoglycemia. Neurosci Lett 264: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SG, Golden SA & Shaham Y. 2008. Differential effects of the hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist SB 334867 on high-fat food self-administration and reinstatement of food seeking in rats. Br J Pharmacol 154: 406–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National_Eating_Disorders_Association. 2016. Binge eating disorder page 19.

- Olney JJ, Navarro M & Thiele TE. 2015. Binge-like consumption of ethanol and other salient reinforcers is blocked by orexin-1 receptor inhibition and leads to a reduction of hypothalamic orexin immunoreactivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39: 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski PK, Shaw TJ, Grace MK, Hoglund CE, Fredriksson R, Schioth HB & Levine AS. 2009. Complexity of neural mechanisms underlying overconsumption of sugar in scheduled feeding: involvement of opioids, orexin, oxytocin and NPY. Peptides 30: 226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overeem S, Mignot E, van Dijk JG & Lammers GJ. 2001. Narcolepsy: clinical features, new pathophysiologic insights, and future perspectives. J Clin Neurophysiol 18: 78–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palus K, Chrobok L & Lewandowski MH. 2015. Orexins/hypocretins modulate the activity of NPY-positive and -negative neurons in the rat intergeniculate leaflet via OX1 and OX2 receptors. Neuroscience 300: 370–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG & Kilduff TS. 1998. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci 18: 9996–10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi PT, Holmes A, Roberts BM & Bailey AM. 2015. Orexin receptor activity in the basal forebrain alters performance on an olfactory discrimination task. Brain Res 1594: 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli L, Micioni Di Bonaventura MV, Cifani C, Costantini VJ, Massagrande M, Montanari D, Martinelli P, Antolini M, Ciccocioppo R, Massi M, Merlo-Pich E, Di Fabio R & Corsi M. 2012. Role of orexin-1 receptor mechanisms on compulsive food consumption in a model of binge eating in female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 1999–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme MJ, Lacroix MC, Badonnel K, Gougis S, Baly C, Salesse R & Caillol M. 2009. Nutritional status modulates behavioural and olfactory bulb Fos responses to isoamyl acetate or food odour in rats: roles of orexins and leptin. Neuroscience 162: 1287–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashmi KS, Mayannavar S, Deshpande K & Ganaraja B. 2015. Involvement of neuropeptide orexin B in basolateral amygdala mediated consummatory behaviour in male wistar albino rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 59: 175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorabaugh JM, Stratford JM & Zahniser NR. 2014. A relationship between reduced nucleus accumbens shell and enhanced lateral hypothalamic orexin neuronal activation in long-term fructose bingeing behavior. PLoS One 9: e95019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ & Yanagisawa M. 1998. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92: 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Moriguchi T, Furuya K, Kajiwara N, Nakamura T, Yanagisawa M & Goto K. 1999. Structure and function of human prepro-orexin gene. J Biol Chem 274: 17771–17776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarihi A, Emam AH, Panah MH, Komaki A, Seif S, Vafaeirad M & Alaii E. 2015. Effects of activation and blockade of orexin A receptors in the medial preoptic area on food intake in male rats. Neurosci Lett 604: 157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauchelli S, Jimenez-Murcia S, Sanchez I, Riesco N, Custal N, Fernandez-Garcia JC, Garrido-Sanchez L, Tinahones FJ, Steiger H, Israel M, Banos RM, Botella C, de la Torre R, Fernandez-Real JM, Ortega FJ, Fruhbeck G, Granero R, Tarrega S, Crujeiras AB, Rodriguez A, Estivill X, Beckmann JS, Casanueva FF, Menchon JM & Fernandez-Aranda F. 2016. Orexin and sleep quality in anorexia nervosa: Clinical relevance and influence on treatment outcome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 65: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammell TE & Winrow CJ. 2011. Orexin receptors: pharmacology and therapeutic opportunities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 51: 243–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schone C & Burdakov D. 2017. Orexin/hypocretin and organizing principles for a diversity of wake-promoting neurons in the brain. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 33: 51–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharf R, Sarhan M & Dileone RJ. 2010. Role of orexin/hypocretin in dependence and addiction. Brain Res 1314: 130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Mondal MS, Date Y, Nakazato M, Suzuki H & Ueta Y. 2008. Distribution of orexins-containing fibers and contents of orexins in the rat olfactory bulb. Neurosci Res 61: 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoblock JR, Welty N, Aluisio L, Fraser I, Motley ST, Morton K, Palmer J, Bonaventure P, Carruthers NI, Lovenberg TW, Boggs J & Galici R. 2011. Selective blockade of the orexin-2 receptor attenuates ethanol self-administration, place preference, and reinstatement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 215: 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples LG & Cornish JL. 2014. The orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 attenuates anxiety in rats exposed to cat odor but not the elevated plus maze: an investigation of Trial 1 and Trial 2 effects. Horm Behav 65: 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet DC, Levine AS, Billington CJ & Kotz CM. 1999. Feeding response to central orexins. Brain Res 821: 535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Chen J, Ramanjaneya M, Punn A, Conner AC & Randeva HS. 2008. The signalling profile of recombinant human orexin-2 receptor. Cell Signal 20: 1651–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrill SJ, Hyde KM, Kay KE, Greene HE, Maske CB, Knierim AE, Davis JF & Williams DL. 2016. Ventral tegmental area orexin 1 receptors promote palatable food intake and oppose postingestive negative feedback. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teske JA, Perez-Leighton CE, Billington CJ & Kotz CM. 2013. Role of the locus coeruleus in enhanced orexin A-induced spontaneous physical activity in obesity-resistant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R1337–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe AJ, Cleary JP, Levine AS & Kotz CM. 2005. Centrally administered orexin A increases motivation for sweet pellets in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 182: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe AJ & Kotz CM. 2005. Orexin A in the nucleus accumbens stimulates feeding and locomotor activity. Brain Res 1050: 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi P, Yu H, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH & Guan XM. 1998. Distribution of orexin receptor mRNA in the rat brain. FEBS Lett 438: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Bakhshishayan S & Kogo M. 2011. Analyses of the facilitatory effect of orexin on eating and masticatory muscle activity in rats. J Neurophysiol 106: 3129–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujino N & Sakurai T. 2009. Orexin/hypocretin: a neuropeptide at the interface of sleep, energy homeostasis, and reward system. Pharmacol Rev 61: 162–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia S, Cornejo MP, Reynaldo M, De Francesco PN & Perello M. 2015. Escalation in high fat intake in a binge eating model differentially engages dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area and requires ghrelin signaling. Psychoneuroendocrinology 60: 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia S, Patrone A, Reynaldo M & Perello M. 2014. Acute high fat diet consumption activates the mesolimbic circuit and requires orexin signaling in a mouse model. PLoS One 9: e87478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Gao XB, Obrietan K, Kilduff TS & Belousov AB. 1998. Presynaptic and postsynaptic actions and modulation of neuroendocrine neurons by a new hypothalamic peptide, hypocretin/orexin. J Neurosci 18: 7962–7971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holst RJ, van der Cruijsen L, van Mierlo P, Lammers GJ, Cools R, Overeem S & Aarts E. 2016. Aberrant food choices after satiation in human orexin-deficient narcolepsy type 1. Sleep 39: 1951–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhaven MW, Cornish JL & Staples LG. 2015. The orexin-1 receptor antagonist SB-334867 decreases anxiety-like behavior and c-Fos expression in the hypothalamus of rats exposed to cat odor. Behav Brain Res 278: 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers SP, Hackett D, Murray F, Hutson PH & Heal DJ. 2015. Effects of lisdexamfetamine in a rat model of binge-eating. J Psychopharmacol 29: 1290–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ, Dringenberg HC & Comery TA. 1992. Rats (Rattus norvegicus) modulate eating speed and vigilance to optimize food consumption: effects of cover, circadian rhythm, food deprivation, and individual differences. J Comp Psychol 106: 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Beuckmann CT, Willie JT, Hara J, Tsujino N, Mieda M, Tominaga M, Yagami K, Sugiyama F, Goto K, Yanagisawa M & Sakurai T. 2003. Hypothalamic orexin neurons regulate arousal according to energy balance in mice. Neuron 38: 701–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, McCormack S, Espana RA, Crocker A & Scammell TE. 2006. Afferents to the orexin neurons of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 494: 845–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajo KN, Fadel JR & Burk JA. 2016. Orexin A-induced enhancement of attentional processing in rats: role of basal forebrain neurons. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233: 639–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J & Luo P. 2002. Orexin B immunoreactive fibers and terminals innervate the sensory and motor neurons of jaw-elevator muscles in the rat. Synapse 44: 106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink AN, Bunney PE, Holm AA, Billington CJ & Kotz CM. 2018. Neuromodulation of orexin neurons reduces diet-induced adiposity. Int J Obes (Lond) 42: 737–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]