Abstract

Background:

Physiotherapists and general practitioners (GPs) both act as primary assessors for patients with musculoskeletal disorders in primary care. Previous studies have shown that initial triaging to physiotherapists at primary healthcare centres has advantages regarding efficiency in the work environment and utilization of healthcare. In this study, we aimed primarily to determine whether triaging to physiotherapists affects the progression of health aspects over time differently than traditional management with initial GP assessment. The secondary aim was to determine whether triaging to physiotherapists affects patients’ attitudes of responsibility for musculoskeletal disorders.

Methods:

This was a pragmatic trial where both recruitment and treatment strategies were determined by clinical, not study-related parameters, and was initiated at three primary care centres in Sweden. Working-age patients of both sexes seeking primary care for musculoskeletal disorders and nurse assessed as suitable for triaging to physiotherapists were randomized to initial consultations with either physiotherapists or GPs. They received self-assessment questionnaires before the initial consultation and were followed up at 2, 12, 26 and 52 weeks with the same questionnaires. Outcome measures were current and mean (3 months) pain intensities, functional disability, risk for developing chronic musculoskeletal pain, health-related quality of life and attitudes of responsibility for musculoskeletal conditions. Trends over time were analysed with a regression model for repeated measurements.

Results:

The physiotherapist-triaged group showed significant improvement for health-related quality of life at 26 weeks and showed consistent but nonsignificant tendencies to greater reductions of current pain, mean pain in the latest 3 months, functional disability and risk for developing chronic pain compared with traditional management. The triage model did not consistently affect patients’ attitudes of responsibility for musculoskeletal disorders.

Conclusions:

Triaging to physiotherapists for primary assessment in primary care leads to at least as positive health effects as primary assessment by GPs and can be recommended as an alternative management pathway for patients with musculoskeletal disorders.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT148611.

Keywords: musculoskeletal disorders, physiotherapy, primary care, RCT, triage

Introduction

Worldwide, the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) has been steadily increasing for many years, leading to an approximate 20% increase in years lived with disability from 2006 to 2016.1 MSDs seen in primary care include a wide range of conditions and account for 14–17% of primary care consultations.2,3 While self-management may suffice for some disorders, others require treatment and some develop over time into chronic conditions which impede daily activities and reduce quality of life in the long term.4 Standard management in primary care traditionally involves primary assessment by general practitioners (GPs). Physiotherapists also see this group of patients, either as primary assessors or after referrals from physicians.5

Primary care in Sweden is generally provided at primary healthcare centres (PHCCs) with several practising GPs and other healthcare professionals. Patients are usually required to register themselves at a PHCC that will assume responsibility for providing first-line medical care which does not require emergency services or hospital resources. Rehabilitation services are organized and financed separately and are often located at separate premises from the PHCCs. There is no need for physician referrals to see physiotherapists in Sweden and referrals do not affect treatment costs. Sweden differs, in this way, from many countries where access to physiotherapists is limited by healthcare regulations or by financial incentives and barriers. However, even in Sweden, patients frequently turn to their PHCC first for all medical issues, even when they could easily consult a physiotherapist directly for certain types of health problems.3

In attempts to improve the management of MSDs in primary care, efforts have been made to include physiotherapists as early as possible in the care of these patients.6,7 Several Swedish PHCCs have implemented a triage model in which nurses screen all patients seeking care using a specially developed handbook which guides them in their decision making.6 Those seeking help for musculoskeletal conditions and showing no obvious symptoms of serious disease or injury are, whenever possible, booked directly to a physiotherapist for initial consultation. The model also provides opportunity for the physiotherapists to contact a GP after the initial consultation if the patient is in need of medical services.

Nurses, physiotherapists and GPs all screen for ‘red flag’ symptoms which may indicate serious illness or risk for chronicity.8–10 While GPs have greater competence regarding the treatment of serious illness, it is possible that physiotherapeutic focus on regaining musculoskeletal function and learning how to handle musculoskeletal conditions independently may be better suited to many of the conditions seen in primary care. Physiotherapist competence in managing musculoskeletal disorders has been demonstrated earlier.11,12 If nurses can successfully identify those patients who are in greater need of physiotherapeutic treatment than GP treatment, then savings in terms of patient suffering and waiting times for treatment may be made by enabling patients to receive appropriate care without unnecessary delays.

The triage model has been shown to have several advantages, such as increased efficiency in the work environment at PHCCs and reduced utilization of GP visits and services over time.6,13 Other models for musculoskeletal triage in Sweden, Canada, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom have also shown positive results for early physiotherapeutic involvement but studies have been predominantly nonrandomized and have focused on aspects such as selection accuracy, waiting times or personnel and patient satisfaction.14,15 In a cohort study, Goodwin and Hendrick found health improvements for patients with MSD who chose physiotherapist over GP as first-line contact.16 The effects of direct triaging to physiotherapists on patients’ health and function have not, to our knowledge, been studied previously with randomised methodology.

Research concerning early initiation of physiotherapy has concentrated on low back pain, with early treatment showing advantages over later onset.17 If appropriate physiotherapeutic treatment is introduced initially, and immediately when patients seek help for all musculoskeletal conditions at PHCCs, perhaps health benefits may be further increased.

The nature of MSDs varies widely but most lead to pain, impaired function, lower quality of life and, in many cases, to an increased risk for developing chronic conditions.18–20 It is possible that the progression of these aspects over time may be affected by the quality and content of initial management by healthcare.

Physiotherapeutic treatment of MSD is generally oriented to regaining function. Specific advice and assistance on lifestyle, ergonomics and exercise can be combined with manual treatment and nonpharmaceutical pain alleviation techniques.21–23 On the other hand, GPs also give advice in their management of MSDs, and may, in addition, prescribe medication, make referrals for radiological examinations to secondary-care specialists and other professions, and, when necessary, provide sick-leave notes.10 While all or some of these latter actions may be necessary, they do not require the patient to actively address their disorder in the way physiotherapeutic instructions or exercise may do. It is possible that initial contact with a physiotherapist may increase the focus on other aspects of the health conditions and encourage patients to take more responsibility for their musculoskeletal health.

Pragmatic trials are used to determine the effectiveness of treatments in routine clinical practice. They require the studied population to be as representative as possible and outcome measures to cover a full range of possible health gains and aim to facilitate informed treatment/management choices.24

The primary aim of the study was to use pragmatic randomized methodology to determine whether direct triaging of patients with musculoskeletal disorders to physiotherapists in primary care affects the health outcomes pain, disability, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and risk for developing chronic conditions differently than traditional management with initial assessment by GPs. The secondary aim was to determine whether triaging to physiotherapists affects patients’ attitudes of responsibility for musculoskeletal disorders differently than traditional management.

Methods

Design and participants

A randomized controlled trial was organized at three PHCCs in Gothenburg, Sweden, where the triage model6 was well established and physiotherapists integrated into normal practice. The data analyst was blinded to group identification until the preliminary analyses were completed.

One PHCC was situated in an area with low socioeconomic conditions where many of the registered patients were recent immigrants with limited command of either Swedish or English; the second in a more affluent area with primarily Swedish-born-registered patients; and the third in an area with a greater mix of backgrounds and socioeconomic levels. This mix is representative of the urban Swedish population. All triage nurses at the PHCCs were informed of the study and invited to participate in the recruiting process. The managers endorsed the study and encouraged the nurses to participate. The nurses’ role was to recruit participants from those patients whom they normally triaged directly to physiotherapists.

Inclusion criteria: working-age patients, 16–67 years of age, of both sexes seeking help for musculoskeletal conditions at the participating PHCCs who could speak sufficient Swedish or English to complete the questionnaires were included in the study. Exclusion criteria: patients requiring home visits, who primarily needed medical aids, or who had ongoing treatment for the current musculoskeletal disorder with relevant healthcare visits during the preceding month were excluded, as were those seeking help for chronic conditions with unchanged symptoms the latest 3 months and who had already tried physiotherapeutic treatment for the same condition. Sampling was consecutive but was dependent on individual assessment by the triage nurse.

The study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Gothenburg (DNR 358-14). All participants provided informed written consent.

Intervention

Randomization was prepared in advance by the project leader using a computer-generated sequence in blocks of 10 and sealed opaque envelopes. After giving informed written consent, participants were randomized by a nurse to a first visit with either a physiotherapist or a GP [treatment as usual (TAU)] and received questionnaires to be filled in before the visit. Besides the outcomes listed below, participants were asked about comorbidities and completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.25 The participants were instructed not to divulge to the caregiver that they were participating in the study. The study protocol did not dictate the treatment each patient received. It only determined which profession would make the first assessment. The participants were followed for 1 year from their first visit and received follow-up questionnaires at 2, 12, 26 and 52 weeks in order to discern both short-term and long-term effects.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes Concerning the first aim of the study, several outcomes were examined. With regards to pain, both current pain and mean pain during the latest 3 months were measured using 11-point numeric pain rating scales, with 10 indicating unbearable pain and 0 indicating no pain.26 The Disability Rating Index (DRI) measured functional disability for 12 different daily activities each on a 100 mm line where the participant marks the difficulty level between the endpoints ‘no difficulty’ and ‘cannot perform’.27 Higher values indicate higher levels of disability. EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ5D) measured HRQoL.28 This is a two-part instrument, with the first giving an index value based on questions concerning mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain and anxiety/depression, and the second part consisting of a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0-100 where the participants indicate their current health state. Risk for developing chronic musculoskeletal pain was measured with the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (ÖMPSQ).29 ÖMPSQ consists of 21 questions concerning present and past pain and ability, as well as expectations for recovery, with possible scores between 3 and 210. Scores < 90 are interpreted as low risk, between 90 and 105 as medium risk, and > 105 as high risk. All of these patient-reported outcome measures have been used extensively in research and clinical environments and have been reliability and validity tested for patients with MSD.26,27,30–35

Secondary outcome The Attitudes regarding Responsibility for Musculoskeletal disorders scale (ARM)36 was used to investigate the secondary aim. Higher scores indicate higher degrees of externalization. ARM is divided into four subscales: the Responsibility Employers (RE) subscale investigates the extent to which people place responsibility for musculoskeletal health on employers; the Responsibility Medical Professionals (RMP) subscale examines how much responsibility is placed on medical professionals; the Responsibility Out of my hands (RO) subscale examines the amount of responsibility which is placed on factors not under control of the individual; the Responsibility Self-Active (RSA) subscale examines the extent to which the individual takes own responsibility for musculoskeletal health. The first three subscales can give values between 3 and 18; the fourth, between 6 and 36.

Data analysis

A sample size of 63 participants/group was aimed for, based on a clinically relevant difference between groups of one unit for current pain with power level 80% and p < 0.05.

Mean values with standard deviations were calculated at baseline and at 12 weeks. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine differences between groups for dichotomized confounders and Student’s t test for continuous confounders and outcome variables.

Linear regression analyses for repeated measurements were used to study the results using a marginal model with unstructured covariance matrix for residuals. Possible confounders (age, sex, comorbidities, depression, Swedish origin) were tested individually. Those with a statistical significance of p > 0.25 and which had <15% effect on the predicted values were excluded from the regression. This method takes into account that repeated measurements on each participant will be dependent on the individual’s baseline value. It adjusts for the effect of confounders and corrects for missing values within a group when estimating differences between groups.

Results

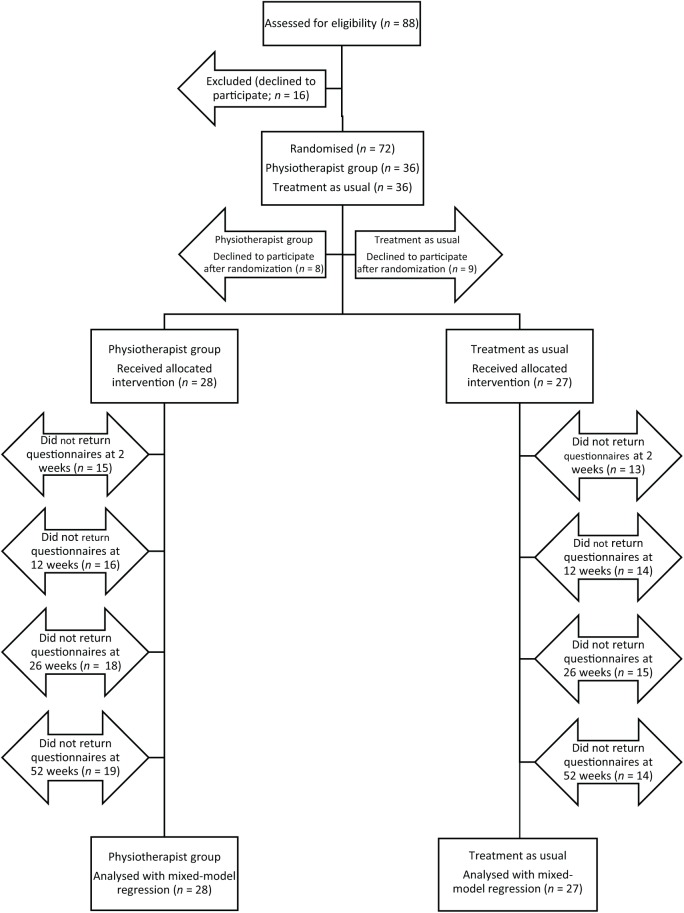

Recruitment to the study was ended early when impending organizational changes at the participating clinics created difficulties with continuing to follow the study protocol. Fifty-five participants were included in the study and randomized to a visit for initial assessment and treatment with a physiotherapist or to TAU (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the participants at baseline. There were no statistically significant differences between groups for any of the possible confounders or for any of the measured outcome variables. The distribution of musculoskeletal conditions was similar in the two groups. The triage visits for both groups were all made within 0–3 working days from time of the nurse screening. During the recruitment period (2014–2016), eight different physiotherapists worked at the participating clinics. The exact number of GPs active at the clinics during the study period is unknown but was several times higher.

Figure 1.

Flowchart from recruitment to mixed-model analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive and outcome statistics.

| Confounder | Triaged to physiotherapist n = 28 |

TAU n = 27 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 39.1 (2.4) | 39.0 (2.5) | 0.992a |

| Range | 18-63 | 18-67 | |

| Sex, nmale (%) | 13 (46) | 9 (33) | 0.331b |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 4 (14) | 3 (11) | 0.730b |

| Depression, n (%) | 3 (11) | 4 (15) | 0.656b |

| Born in Sweden, n (%) | 13 (46) | 18 (67) | 0.135b |

| Triage reason | 7 lower extremity 10 upper extremity/neck 10 back 1 multiple regions |

11 lower extremity 7 upper extremity/neck 9 back |

|

| Outcome variable | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p a |

| Risk for chronicity | 98.9 (25.8) | 102.0 (26.1) | 0.652 |

| Disability | 38.6 (20.1) | 39.5 (25.5) | 0.887 |

| Current pain | 7.1 (2.4) | 6.6 (2.4) | 0.486 |

| Mean pain | 5.7 (2.4) | 4.8 (2.9) | 0.237 |

| HRQoL | 0.50 (0.32) | 0.59 (0.25) | 0.254 |

| HRQoL-VAS | 57.5 (20.8) | 63.2 (25.7) | 0.415 |

| ARMTotal | 42.0 (10.0) | 45.4 (10.1) | 0.225 |

| ARMRE | 8.4 (4.5) | 9.0 (3.7) | 0.568 |

| ARMRMP | 11.6 (3.9) | 12.1 (3.6) | 0.630 |

| ARMRO | 8.3 (3.2) | 8.7 (3.6) | 0.612 |

| ARMRSA | 13.8 (4.9) | 15.3 (4.9) | 0.257 |

Student’s t test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Comorbidities = have any of the diseases diabetes, hypertension, chronic ischaemic heart disease, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Risk for chronicity measured with Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire; disability with Disability Rating Index; current pain and mean pain with 11-point numeric pain rating scales; and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) with EQ-5D (EuroQol 5 dimensions) index and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

ARM, Attitudes of Responsibility for Musculoskeletal disorders scale; RE, Responsibility Employers; RMP, Responsibility Medical Professionals; RO, Responsibility Out of my hands; RSA, Responsibility Self-Active; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as usual.

Many patients who agreed to participate in the study failed to send back all or some of the follow-up questionnaires (Figure 1). Three informed the project manager they no longer wished to participate, others merely failed to send back some or all of their questionnaires, in spite of reminders. Largest dropout was directly after inclusion with consequently discontinued participation. A few missed one or more follow ups but then participated once again. An analysis of the missing values indicated a missing-at-random (MAR) pattern with a significant effect of age in the physiotherapist group. Younger participants who had been triaged to physiotherapists failed to send in their follow-up questionnaires to a greater extent than older participants. There was no significant age effect in the TAU group. All randomized participants who received the allocated intervention were included in the statistical analysis according to intention to treat with the statistical model compensating for internal missing values. No adverse events were reported.

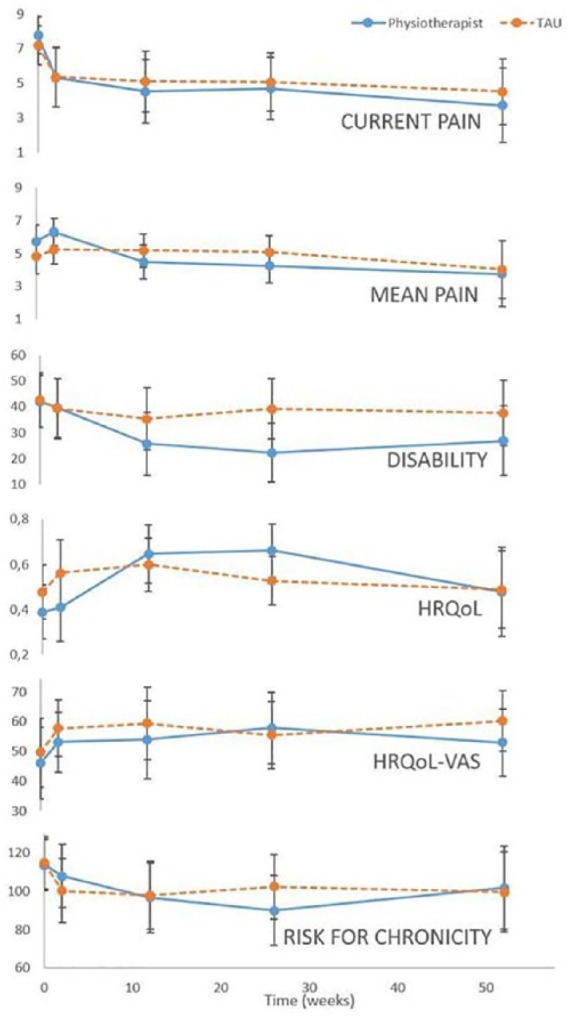

Health effects: at 12 weeks, there were no significant differences between groups but tendencies to positive effects for all variables were noted for the physiotherapist group (Table 2). Over the year-long follow up, the regression analyses showed greater positive effect for the physiotherapist group on several health outcomes in comparison with TAU, with HRQoL reaching statistical significance (p = 0.014) and functional disability, near significance (p = 0.098). Current pain (p = 0.831) and mean pain (p = 0.168) were slightly, but consequently, lower for the physiotherapist group. Risk for chronicity was somewhat lower in the physiotherapist group at 6 months (p = 0.288) but this difference disappeared at 1 year. Both groups decreased their risk level from medium to low over the year. HRQoL-VAS varied over time between groups. See Figure 2 for adjusted data over time and supplementary data for regression details.

Table 2.

Health and attitude outcomes at 12 weeks.

| Outcome variable | Triaged to physiotherapist n = 12 Mean (SD) |

TAU n = 13 Mean (SD) |

p a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk for chronicity | 73.6 (25.7) | 86.8 (34.3) | 0.291 |

| Disability | 22.8 (11.4) | 34.0 (23.6) | 0.148 |

| Pain | 3.7 (2.7) | 4.8 (3.3) | 0.336 |

| Mean pain | 4.5 (2.4) | 5.5 (1.8) | 0.271 |

| HRQoL | 0.78 (0.06) | 0.72 (0.23) | 0.438 |

| HRQoL-VAS (n = 10) | 71.40 (15.2) | 71.1 (19.0) | 0.969 |

| ARMTotal | 39.1 (11.1) | 44.2 (9.9) | 0.237 |

| ARMRE | 7.2 (4.1) | 8.1 (4.4) | 0.598 |

| ARMRMP | 9.7 (5.4) | 13.5 (3.9) | 0.049 |

| ARMRO | 7.6 (3.2) | 7.8 (3.7) | 0.852 |

| ARMRSA | 14.7 (5.8) | 14.7 (4.8) | 0.990 |

Student’s t test.

Bold values indicate statistical significance. Risk for chronicity measured with Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire; disability with Disability Rating Index; current pain and mean pain with 11-point numeric pain rating scales; and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) with EQ-5D (EuroQol 5 dimensions) index and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

ARM, Attitudes of Responsibility for Musculoskeletal disorders scale; RE, Responsibility Employers; RMP, Responsibility Medical Professionals; RO, Responsibility Out of my hands; RSA, Responsibility Self-Active; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as usual.

Figure 2.

Health outcomes over time, predicted values from regression analyses.

HRQoL, health-related quality of life; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

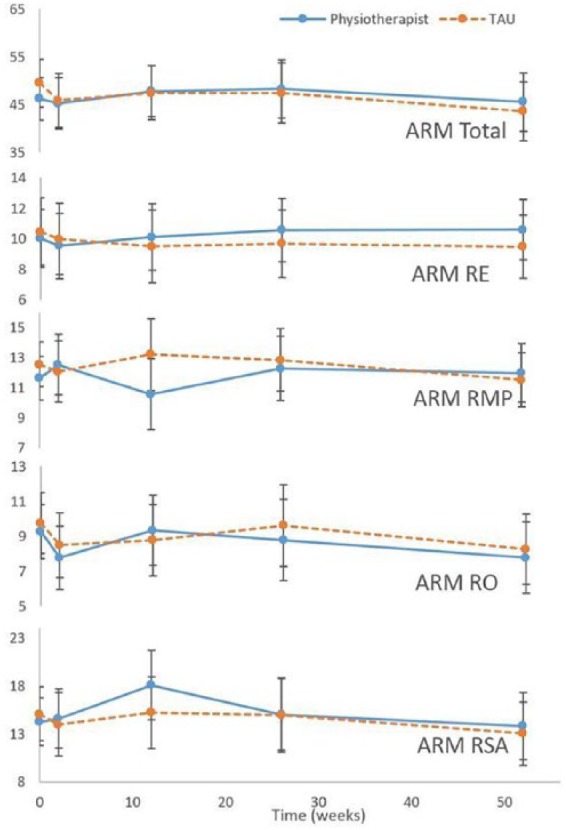

Attitudes of responsibility for musculoskeletal disorders: At 12 weeks, the RMP subscale showed significantly less externalization in the physiotherapist group (Table 2). Over the year-long follow up, the regression analyses showed significantly less externalization for RMP in the physiotherapist group compared with TAU (p = 0.025), a tendency for the physiotherapist group to express more externalization towards employers (p = 0.322) and at 3 months, increased externalization in relation to own responsibility (p = 0.505). See Figure 3 for adjusted data over time and supplementary data for regression details.

Figure 3.

Attitudes of responsibility for musculoskeletal disorders (ARM) and subscales over time, predicted values from regression analyses.

RE, Responsibility Employer; RMP, Responsibility Medical Professionals; RO, Responsibility Out of my hands; RSA, Responsibility Self-Active.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of randomizing nurse-assessed patients with musculoskeletal disorders to physiotherapists in primary care for initial consultation and compared with traditional management. In spite of difficulties in the recruiting process and considerable loss to follow up, consistent differences between groups regarding health outcomes which favour triaging to physiotherapists could be discerned.

Treatment effects

Design of the triage model focused on immediate physiotherapeutic examination and treatment of MSDs with recent debut or recent flare up.6 More involved and long-term rehabilitation could be handled more appropriately externally at larger rehabilitation clinics. This focus explains the relatively low mean age of the participants and, perhaps, helps explain the large dropout after inclusion. Many patients sought help for minor pain and injuries with good prognosis for recovery. Reassuring advice on how to handle the situation was, in some cases, all that was needed. When physiotherapists are not included as standard primary care personnel, it is possible that this group of patients may be left to self-management. In certain cases, however, minor pain and injuries can develop into long-term conditions if not handled optimally.37 Risk assessment tools such as ÖMPSQ or the STarT Back tool may help clinicians to steer patients along appropriate management pathways.38,39 Many studies have indicated that early contact with physiotherapists can lead to more favourable clinical outcomes, but there is a lack of studies aimed at assessment by physiotherapists before or instead of GP assessment.40,41 This study indicates that early contact with both GPs and physiotherapists can reduce the risk for patients developing chronic conditions with subsequent need for more comprehensive medical treatment. As the effects of physiotherapist treatment were at least as good as TAU, it is clearly feasible to impose management modifications which can free medical competence for other patient groups. It is important to take care of even the group of patients with short-term or low-intensive musculoskeletal conditions to prevent development of chronic disorders.

Physiotherapeutic treatment of musculoskeletal conditions seen in primary care has a strong focus on reduction of functional disability. GPs are, generally, not as involved in specific treatment of disability but will often refer to physiotherapists when this type of problem occurs.42,43 Initiating active focus on disability immediately seems to lead to an advantageous clinical course.

Many patients seeking help for acute musculoskeletal pain may feel that they are in need of pain medication during the acute phase. A major difference between physiotherapist and GP management strategies is the possibility for the GPs to prescribe medication when they deem it necessary. There were several different physiotherapists receiving patients in the study, each with their own experience level and skill set. However, the results clearly show that pain levels decreased immediately and to the same level for both the intervention and control groups during the first 2 weeks, with further comparative reductions for the physiotherapist group during the subsequent months. This may, in part, be due to the natural course for MSDs with recent debut. Some studies recommend physiotherapist involvement first when the acute phase changes to subacute because of the frequent need for pain medication.42 However, it would seem that physiotherapeutic strategies have comparable effects with GP strategies on pain in the initial stages of treatment of MSDs.

HRQoL is an important aspect regarding musculoskeletal health. Musculoskeletal conditions are often recurring in nature and, therefore, it is not always a question of being ‘cured’ so much as learning how to handle and live with certain conditions.37,44 A patient who has learned how to keep musculoskeletal pain under control may have increased HRQoL in spite of continued pain or pain episodes. Patient education is an integral component of physiotherapy treatment for MSDs and has been shown to have good effect on pain management and on lifestyle modifications.23,45,46 Goodwin and Hendrick’s study comparing first-line physiotherapy to GP-initiated treatment also found that HRQoL increased in the physiotherapy group.16

While most of the differences between groups were nonsignificant, the health-based outcomes showed common tendencies with HRQoL, functional disability, pain, and risk for developing chronic pain all showing better or slightly better values for the physiotherapist group. So, while it cannot be irrevocably concluded that initial treatment by physiotherapists is better for all patients with musculoskeletal disorders than medical advice and treatment by a GP, there is nothing to indicate that this triage model for managing patients with musculoskeletal disorders in primary care is, in any way, detrimental to the patients’ health or worse than standard care. Only positive effects were notable and no adverse events regarding the triaging process were reported. This is congruent with previous studies in this area.7,16

The secondary aim of the study concerned patients’ attitudes of responsibility for MSDs. It is known that persons with MSDs acknowledge both own responsibility for their state of health and view external forces/events as having impact.44,47 If treatment based on medication is offered first, patients may learn that it is necessary to take medication to solve musculoskeletal health problems. If treatment based on exercise and condition-specific advice is presented first, patients may learn to handle their musculoskeletal conditions more independently. The differences between groups based on ARM are mostly nonsignificant and, unlike the health-based outcomes, they do not show common tendencies and are, therefore, more difficult to interpret. The differences between groups at 3 months were not maintained over time. A larger study population may be necessary to properly understand the effects of triaging on patient attitudes.

Nurse assessments formed the basis of the triage model. Nurse ability to triage efficiently has been demonstrated earlier in primary care,6 as has their ability to use professional judgement in combination with structured guidelines in order to plan relevant care for each patient.8 Most of the patients in the physiotherapist group were shown to have better health outcomes over time, which supports the conclusion that nurses have the competence to discern between appropriate and inappropriate patients for direct triaging to physiotherapists.

Methodological considerations

A strength of the study is the pragmatic design, making the intervention easy to implement in the clinical environment. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated based on the characteristics of the patient groups which were commonly triaged to physiotherapists at the clinics, aiming to make it as easy as possible for the nurses to understand and follow the study protocol and to facilitate future implementation. Results of research studies with carefully controlled and limiting parameters are not always directly applicable to clinical environments and even studies showing clear positive effects of an intervention often have trouble leading to clinical implementation.48,49

Another strength is that the caregivers in the study were unaware of which patients were study participants. True blinding of patient or caregiver was not possible, as the intervention involved direct personal contact. All caregivers, with the exception of temporary personnel, were aware that the study was in progress but were simply unaware of when one of their patients was a study participant and were, at all times, to continue with TAU.

A weakness of the study is the low number of participants. It was difficult to motivate the nurses to recruit participants. A large majority of patients who were triaged to physiotherapists during the 2-year recruitment period were never asked to participate. An analysis of the barriers affecting the recruitment process led to three major issues: difficulty understanding the research protocol; time constraints; and unwillingness to risk being obliged to give visiting times to GPs, which were in high demand, to patients suitable for triaging to physiotherapists. Similar barriers have been found in earlier studies.50 Feedback, incentives and expressed appreciation were used to encourage continued recruitment of participants over a 2-year period.51,52 Planned organizational changes in the region made it unlikely that it would be possible to continue to have physiotherapists located at the participating clinics and so recruitment was discontinued early. Those already enrolled in the study were followed for the remainder of each participant’s individual year. There remains a need for larger studies to further explore this area.

Of those participants who were recruited, many failed to complete their follow ups. There was a substantial dropout directly after inclusion in both groups. The analysis of missing values indicated that younger people in the physiotherapist group failed to respond to follow up to a higher degree than in the TAU group. There were no differences between groups in dropouts regarding other potential confounders. One way of interpreting this is that those who recovered completely in a short period of time subsequently lost interest in answering questions about their health conditions or did not know how to answer the questions when they no longer had a problem. In the few cases where a reason was given for dropping out, this was one of the reasons expressed. Perhaps younger people recovered more quickly in the physiotherapist group than with TAU. If this is so, the results would underestimate the positive effects of triaging to physiotherapists. It would be relevant to attempt to reduce dropout by repeating the study with increased information and support to participating triage nurses, as well as with research-trained personnel taking responsibility for informing and following up participants after the initial clinical assessment by the triage nurse.

Conclusion

The results of this pragmatic study support using physiotherapists for initial assessment of patients with MSD in primary care and indicate that nurses have the necessary competence to discern which patients are appropriate for triaging to physiotherapists. Triaging to physiotherapists for primary assessment in primary care seems to lead to at least as positive health effects as primary assessment by GPs and can be recommended as an alternative management pathway for patients with MSDs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_data for Health effects of direct triaging to physiotherapists in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial by Lena Bornhöft, Maria EH Larsson, Lena Nordeman, Robert Eggertsen and Jörgen Thorn in Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease

Footnotes

Authors’ note: Primary data may be accessed by contacting the first author.

Funding: This work was supported by The Healthcare subcommittee, Region Västra Götaland (461251).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Lena Bornhöft  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7434-658X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7434-658X

Contributor Information

Lena Bornhöft, Göteborgs universitet Sahlgrenska Akademin, Box 455, Gothenburg 405 30, Sweden.

Maria EH Larsson, Göteborgs universitet Sahlgrenska Akademin, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Lena Nordeman, Göteborgs universitet Sahlgrenska Akademin, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Robert Eggertsen, Göteborgs universitet Sahlgrenska Akademin, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Jörgen Thorn, Göteborgs universitet Sahlgrenska Akademin, Gothenburg, Sweden.

References

- 1. Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017; 390: 1211–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jordan KP, Kadam UT, Hayward R, et al. Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mansson J, Nilsson G, Strender LE, et al. Reasons for encounters, investigations, referrals, diagnoses and treatments in general practice in Sweden–a multicentre pilot study using electronic patient records. Eur J Gen Pract 2011; 17: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25: 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moffatt F, Goodwin R, Hendrick P. Physiotherapy-as-first-point-of-contact-service for patients with musculoskeletal complaints: understanding the challenges of implementation. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2017; 19: 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thorn J, Maun A, Bornhoft L, et al. Increased access rate to a primary health-care centre by introducing a structured patient sorting system developed to make the most efficient use of the personnel: a pilot study. Health Serv Manage Res 2010; 23: 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ludvigsson ML, Enthoven P. Evaluation of physiotherapists as primary assessors of patients with musculoskeletal disorders seeking primary health care. Physiotherapy 2012; 98: 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johannessen LEF. Beyond guidelines: discretionary practice in face-to-face triage nursing. Sociol Health Illn 2017; 39: 1180–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leerar PJ, Boissonnault W, Domholdt E, et al. Documentation of red flags by physical therapists for patients with low back pain. J Man Manip Ther 2007; 15: 42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al. Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 2006; 15(Suppl. 2): S169–S191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Childs JD, Whitman JM, Sizer PS, et al. A description of physical therapists’ knowledge in managing musculoskeletal conditions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005; 6: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jette DU, Ardleigh K, Chandler K, et al. Decision-making ability of physical therapists: physical therapy intervention or medical referral. Phys Ther 2006; 86: 1619–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bornhoft L, Larsson ME, Thorn J. Physiotherapy in primary care triage - the effects on utilization of medical services at primary health care clinics by patients and sub-groups of patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a case-control study. Physiother Theory Pract 2015; 31: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McEvoy C, Wiles L, Bernhardsson S, et al. Triage for patients with spinal complaints: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Res Int 2017; 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marks D, Comans T, Bisset L, et al. Substitution of doctors with physiotherapists in the management of common musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2017; 103: 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodwin RW, Hendrick PA. Physiotherapy as a first point of contact in general practice: a solution to a growing problem? Prim Health Care Res Dev 2016; 17: 489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ojha HA, Wyrsta NJ, Davenport TE, et al. Timing of physical therapy initiation for nonsurgical management of musculoskeletal disorders and effects on patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2016; 46: 56–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caplan N, Robson H, Robson A, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) dimensions associated with community-based musculoskeletal physiotherapy: a multi-centre analysis. Qual Life Res 2018; 27: 2373–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andersen LN, Kohberg M, Juul-Kristensen B, et al. Psychosocial aspects of everyday life with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Scand J Pain 2014; 5: 131–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grotle M, Brox JI, Veierod MB, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: patients consulting primary care for the first time. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005; 30: 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beattie PF, Nelson RM, Basile K. Differences among health care settings in utilization and type of physical rehabilitation administered to patients receiving workers’ compensation for musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil 2013; 23: 347–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shariat A, Cleland JA, Danaee M, et al. Effects of stretching exercise training and ergonomic modifications on musculoskeletal discomforts of office workers: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Phys Ther 2018; 22: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Policy statement: description of physical therapy. London, UK: WCPT, www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-descriptionPT (accessed 10 March 2017).

- 24. Roland M, Torgerson DJ. Understanding controlled trials: what are pragmatic trials? BMJ 1998; 316: 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002; 52: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Safikhani S, Gries KS, Trudeau JJ, et al. Response scale selection in adult pain measures: results from a literature review. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017; 2: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salen BA, Spangfort EV, Nygren AL, et al. The disability rating index: an instrument for the assessment of disability in clinical settings. J Clin Epidemiol 1994; 47: 1423–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. EuroQol Group. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1990; 16: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Linton SJ, Hallden K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain 1998; 14: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parsons H, Bruce J, Achten J, et al. Measurement properties of the Disability Rating Index in patients undergoing hip replacement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54: 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grotle M, Garratt AM, Jenssen HK, et al. Reliability and construct validity of self-report questionnaires for patients with pelvic girdle pain. Phys Ther 2012; 92: 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grobet C, Marks M, Tecklenburg L, et al. Application and measurement properties of EQ-5D to measure quality of life in patients with upper extremity orthopaedic disorders: a systematic literature review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018; 138: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hurst NP, Kind P, Ruta D, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: validity, responsiveness and reliability of EuroQol (EQ-5D). Br J Rheumatol 1997; 36: 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain 2003; 19: 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Westman A, Linton SJ, Ohrvik J, et al. Do psychosocial factors predict disability and health at a 3-year follow-up for patients with non-acute musculoskeletal pain? A validation of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain 2008; 12: 641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larsson MEH, Nordholm LA. Attitudes regarding responsibility for musculoskeletal disorders: instrument development. Physiother Theory Pract 2004; 20: 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dorner TE, Crevenna R. Preventive aspects regarding back pain. Wien Med Wochenschr 2016; 166: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hill JC, Dunn KM, Main CJ, et al. Subgrouping low back pain: a comparison of the STarT Back tool with the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Eur J Pain 2010; 14: 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 378: 1560–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nordeman L, Nilsson B, Möller M, et al. Early access to physical therapy treatment for subacute low back pain in primary health care: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Clin J Pain 2006; 22: 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Slater MA, Weickgenant AL, Greenberg MA, et al. Preventing progression to chronicity in first onset, subacute low back pain: an exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Poitras S, Durand MJ, Cote AM, et al. Guidelines on low back pain disability: interprofessional comparison of use between general practitioners, occupational therapists, and physiotherapists. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012; 37: 1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Artus M, van der Windt DA, Afolabi EK, et al. Management of shoulder pain by UK general practitioners (GPs): a national survey. BMJ Open 2017; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wiitavaara B, Bengs C, Brulin C. Well, I’m healthy, but… – lay perspectives on health among people with musculoskeletal disorders. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 38: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bodes Pardo G, Lluch Girbes E, Roussel NA, et al. Pain neurophysiology education and therapeutic exercise for patients with chronic low back pain: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2018; 99: 338–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frerichs W, Kaltenbacher E, Van de Leur JP, et al. Can physical therapists counsel patients with lifestyle-related health conditions effectively? A systematic review and implications. Physiother Theory Pract 2012; 28: 571–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hughner RS, Kleine SS. Views of health in the lay sector: a compilation and review of how individuals think about health. Health (N Y) 2004; 8: 395–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bernhardsson S, Lynch E, Dizon JM, et al. Advancing evidence-based practice in physical therapy settings: multinational perspectives on implementation strategies and interventions. Phys Ther 2017; 97: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 2003; 362: 1225–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, et al. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52: 1143–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yawn BP, Dietrich A, Graham D, et al. Preventing the voltage drop: keeping practice-based research network (PBRN) practices engaged in studies. J Am Board Fam Med 2014; 27: 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fletcher B, Gheorghe A, Moore D, et al. Improving the recruitment activity of clinicians in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e000496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_data for Health effects of direct triaging to physiotherapists in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial by Lena Bornhöft, Maria EH Larsson, Lena Nordeman, Robert Eggertsen and Jörgen Thorn in Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease