Abstract

Introduction

Patients with positive tauopathy but negative Aβ42 (A−T+) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) represent a diagnostic challenge. The Aβ42/40 ratio supersedes Aβ42 and reintegrates “false” A−T+ patients into the Alzheimer's disease spectrum. However, the biomarker and clinical characteristics of “true” and “false” A−T+ patients remain elusive.

Methods

Among the 509 T+N+ patients extracted from the databases of three memory clinics, we analyzed T+N+ patients with normal Aβ42 and compared “false” A−T+ with abnormal Aβ42/40 ratio and “true” A−T+ patients with normal Aβ42/40 ratio, before CSF analysis and at follow-up.

Results

24.9% of T+N+ patients had normal Aβ42 levels. Among them, 42.7% were “true” A−T+. “True” A−T+ had lower CSF tauP181 than “false” A−T+ patients. 48.0% of “true” A−T+ patients were diagnosed with frontotemporal lobar degeneration before CSF analysis and 64.0% at follow-up, as compared with 6% in the “false” A−T+ group (P < .0001).

Discussion

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is probably the main cause of “true” A−T+ profiles.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, Aβ42/40 ratio, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, Frontotemporal dementia, Suspected non Alzheimer's disease pathology (SNAP)

Highlights

-

•

Dementia with normal cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 yet high cerebrospinal fluid tau181P is a situation referred to as A−T+N+ in the 2018 National Institute of Aging–Alzheimer's Association research framework.

-

•

The interpretation of A−T+N+ profiles is not consensual and uncomfortable for clinicians.

-

•

The use of Aβ42/40 ratio as a surrogate amyloid marker halves the number of uninformative A−T+N+ profiles.

-

•

T+N+ patients with normal Aβ42 yet abnormal Aβ42/40 have an Alzheimer's phenotype.

-

•

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is probably the leading cause of A−T+N+ profiles.

1. Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers have redesigned Alzheimer's disease (AD) diagnosis [1], [2], [3]. The major interest of CSF biomarkers rests upon their reflection of brain pathology: several studies have shown that CSF Aβ42 levels are inversely correlated with cerebral Aβ load [4], [5], [6], whereas increased CSF total tau (T-tau) and phosphorylated tau (tau181P) levels reflect the burden of neurofibrillary pathology [6], [7], [8]. Although CSF T-tau is an unspecific marker of neuronal death [9], [10], [11], tau181P and Aβ42 have a high specificity for AD. Tau181P is not or slightly increased in other tauopathies and was shown to outperform the two other biomarkers taken in isolation for differential dementia diagnosis [12], [13], [14], [15]. In 2018, the AT(N) classification system proposed by the 2018 National Institute of Aging–Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) research framework shifted the definition of AD from a syndromal to a biological construct [16]. This system validates CSF Aβ42 and tau181P as suitable markers for amyloid (A) and tau (T) pathology, respectively, while T-tau is considered as a marker of neuronal injury [16], [17]. In the AT(N) scheme, AD patients are A+T+ by definition.

According to Jack's model, there is a temporal ordering of biomarker abnormalities in which biomarkers of Aβ deposition become abnormal before biomarkers of tau pathology and neuronal injury [18]. So far, longitudinal studies show that most AD patients fit into this model [19], [20]. However, a vast number of patients present with A−T+ CSF profiles, that is, with abnormal tau and normal Aβ biomarkers [21], [22], [23], [24]. This possibility of “conflicting” results was anticipated in the 2011 NIA-AA criteria for AD diagnosis. In such instances, biomarkers were deemed “uninformative,” suggesting that results should simply not be taken into account [25], [26]. The recent AT(N) classification system goes one step further, as A−T+ patients are now labeled “suspected non-Alzheimer's pathophysiology” (SNAP) [16], [27].

In recent years, a growing interest for the mechanisms of amyloid precursor protein cleavage has prompted the development of ELISA kits specific for other Aβ species. In the CSF, the most abundant isoform is Aβ40, whose levels show substantial interindividual variations. Because CSF Aβ42 concentration may also depend on overall Aβ levels, it was suggested that an imbalance between CSF Aβ42 and Aβ40 (i.e., a decreased Aβ42/40 ratio) could supersede the mere decrease of CSF Aβ42 level as a biomarker of amyloid pathology [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. Indeed, Aβ42/40 ratio was better correlated than Aβ42 with amyloid tracer retention in two positron emission tomography studies [31], [32]. Using the Aβ42/40 ratio allows to reclassify half of A−T+ patients (hereafter referred to as “false” A−T+, that is, abnormal CSF tau markers and normal Aβ42 but abnormal Aβ42/40 ratio) into the A+T+ group [33], [34]. Despite the relative scarcity of validation studies, the AT(N) system readily recognizes the Aβ42/40 ratio as a surrogate marker of amyloid pathology [16].

However, the clinical phenotype of A−T+ patients remains poorly studied. Positing that Aβ42/40 is the best CSF amyloid biomarker, “false” A−T+ patients should be clinically indistinguishable from A+T+ patients. Conversely, when using the Aβ42/40 ratio instead of Aβ42, 10% to 13% of patients still display a “true” A−T + CSF profile (i.e., abnormal CSF tau markers and normal Aβ42 and Aβ42/40 ratio) [33], [34]. “True” A−T+ patients should have a clinical phenotype that differs from the one of both “false” A−T+ and typical A+T+ patients. In this context, the objectives of this retrospective multicenter study were to (1) determine the proportion of A−T + CSF profiles in routine clinical care; (2) compare the clinical diagnoses made before CSF analysis; and (3) compare the clinical phenotype at follow-up in A−T+ patients separated according to the Aβ42/40 ratio.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were recruited between November 14, 2012 and December 31, 2015 from Paris, Lille, and Nantes Memory Resource and Research Centres (MMRC). Inclusion criteria were fivefold: (1) available CSF with AD biomarkers, including Aβ42, Aβ40, T-tau, and tau181P (quantitative determination of Aβ40 and Aβ42/40 ratio is routine in the three memory clinics); (2) high CSF tau181P (tau181P ≥ 60 pg/mL); (3) mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia; (4) presence of biomarkers of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury (N+) on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET or MRI, and/or high CSF total-tau [16]; and (5) available medical records and neuropsychological assessments performed before the results of CSF biomarkers were made available. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) subjective cognitive decline; (2) unconventional indications of AD CSF biomarkers analysis (e.g., systematic biomarkers analysis following a lumbar puncture [LP] performed for another indication); (3) significant comorbidities, including concomitant nondegenerative and nonvascular neurological disorder.

2.2. Clinical diagnoses

All recruiting centers were tertiary referral memory clinics. These centers use the same clinical and biochemical procedures and international validated criteria for AD and all other dementia. Patients had a thorough examination, including clinical, neurological, and neuropsychological evaluations and brain imaging, as recommended by the Haute Autorité de Santé (French Health Authority). We collected the diagnosis made by the clinician before the LP and the last diagnosis made after the LP at follow-up. To avoid the bias due to the knowledge of CSF biomarkers results, the main analysis was based on the diagnosis evoked by the clinician before the CSF results.

In addition, medical records and neuroimaging studies were analyzed in retrospect by H.P.C., T.B.N., C.P., and T.L., and confronted to current diagnostic criteria. We used the 2011 NIA-AA criteria for probable AD dementia [26]. At the MCI stage, AD diagnosis was only raised when the MCI clinical and cognitive syndrome was consistent with AD, according to the NIA-AA criteria [25]. Vascular cognitive impairment, behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), primary progressive aphasia (PPA) syndromes, Lewy body dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome (PSPS), and corticobasal syndrome (CBS) were defined according to the corresponding criteria [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. In case of discrepancy with the clinician's diagnosis, another diagnosis was suggested.

AD was deemed atypical in case of posterior cortical syndrome, primary logopenic aphasia or frontal/executive variant, as well as in mixed disease (concomitant vascular cognitive impairment and/or Lewy body disease) or when neuroimaging studies were not congruent with AD.

2.3. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis

LPs were performed using a 25-gauge needle, and CSF samples were collected in a 5-mL polypropylene tube in Nantes (catalog number 62.558.201; Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) or in a 10-mL polypropylene tube in Lille and Paris (catalog number 62.610.201; Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). Each CSF sample was transferred at 4°C to the corresponding local laboratory within 4 hours after collection and was then centrifuged at 1000 g (Lille and Paris) or 2100 g (Nantes) for 10 minutes at 4°C. A small amount of CSF was used to perform routine analyses, including total cell count, bacteriological examination, and total protein and glucose levels. The CSF was aliquoted in 1.5-mL polypropylene tubes (Lille and Paris) or 2-mL polypropylene tubes (Nantes) and stored at −80°C to await further analysis. CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, T-tau, and tau181P were measured in each local laboratory using a commercially available sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (INNOTEST; Fujirebio Europe NV, Gent, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. AD biomarker cutoffs

Cutoff values used in clinical routine for P-tau were based on the results of the French multicenter study setting up the harmonization of sampling procedures and collection tubes, to which the three MRRCs involved in the current work participated [41]. Cutoff values for Aβ42 and Aβ42/40 were set at, respectively, <800 pg/mL and <0.065 following another French multicenter study involving our two of our three MMRCs [34]. Pathological results were defined as follows: Aβ42 <800 pg/mL, T-tau ≥350 pg/mL, and tau181P ≥ 60 pg/mL.

Although the AT(N) classification system is intended for research and not for clinical practice [16], we chose to use its nomenclature for brevity. A+T+ profiles were defined by tau181P ≥ 60 pg/mL and Aβ42 <800 pg/mL. A−T+ profiles were defined by tau181P ≥ 60 pg/mL and Aβ42 ≥800 pg/mL. A−T + CSF profiles were further subdivided into “false” A−T+ profiles (Aβ42/40 ratio <0.065, congruent with the presence of amyloid pathology) and “true” A−T+ profiles (normal Aβ42/40 ratio ≥0.065, congruent with the absence of amyloid pathology).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Normality of distributions was assessed graphically and using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

“True” and “false” A−T+ patients were compared using chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test when the expected cell frequency was <5) for qualitative variables, and Student t-test (or Mann-Whitney U test in case of non-Gaussian distribution) for quantitative variables.

In the “True” A−T+ patient group, different parameters were compared according to diagnosis before CSF results. Qualitative parameters were analyzed using chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Analysis of variance (or Kruskal-Wallis test in case of non-Gaussian distribution) was used for quantitative parameters.

A sensitivity analysis was systematically performed by including the study site (Lille, Nantes, or Paris) as a covariate, using a logistic regression to compare “true” and “false” A−T+ patients.

Statistical testing was performed at the two-tailed α level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SAS software package, release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

The study included 1253 patients who underwent a CSF study for biomarker analysis, among which 509 (40.6%) had pathological levels of tau181P.

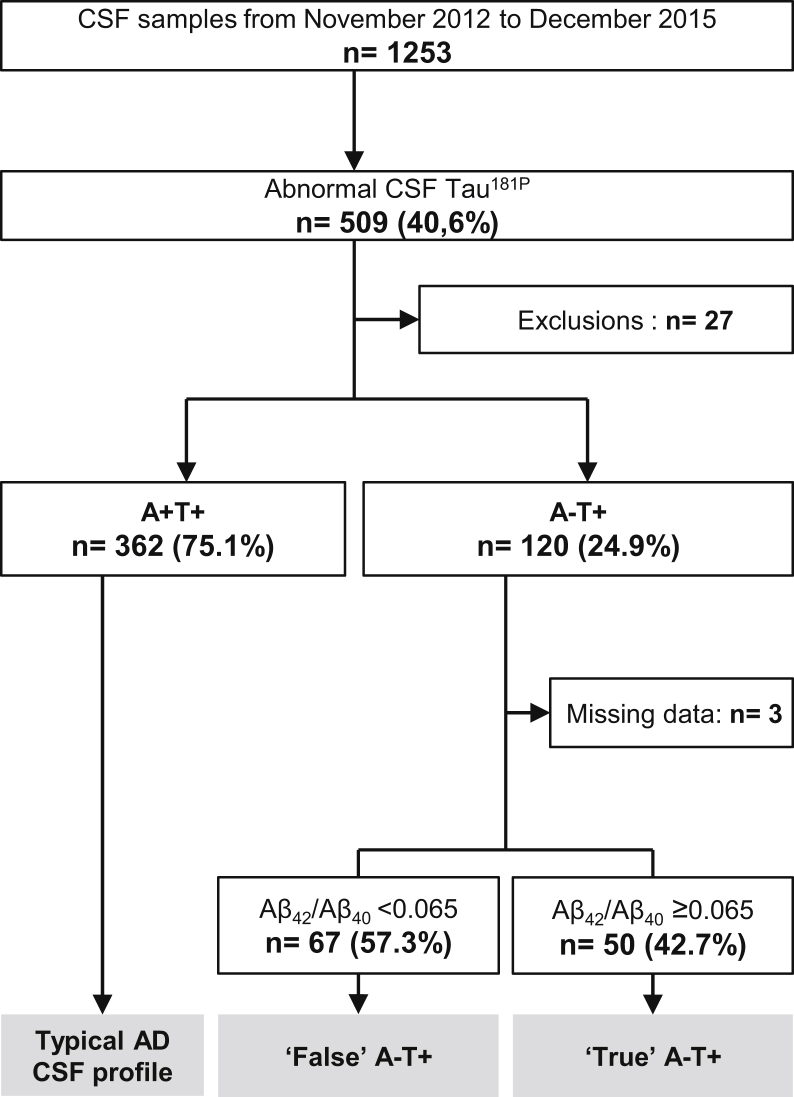

The population of the study was further divided according to Aβ42/40 ratio. Most of the patients with pathological levels of tau181P were A+T+ (n = 362, 75.1%). One hundred twenty patients were A−T+ (24.9% of patients with pathological tau181P, and 9.8% of all patients). Within this subgroup, 67 (57.3%) had abnormal Aβ42/40 ratios (“false” A−T+ profiles) while 50 (42.7%) had normal Aβ42/40 ratios (“true” A−T+ profiles) (Fig. 1). Hence, Aβ42/40 ratio allowed reclassifying more than half of the A−T+ patients into the AD spectrum.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart. CSF profiles were determined following the ATN classification system: A+ corresponds to abnormal Aβ42, T+ to abnormal tau181P. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

3.2. CSF biomarkers in “true” and “false” A−T+ patients

CSF biomarker levels were statistically different between both groups (Table 1). “False” A−T+ patients had lower Aβ42 and higher Aβ40 levels (978.3 ± 216.8 and 20,334.1 ± 4972.4) as compared with “true” A−T+ patients (1313.3 ± 329.1 and 15,367.5 ± 4091.0; P < .001 and P < .001).

Table 1.

Comparisons between “false” and “true” A−T+ groups

| “False” A−T + Aβ42/40 <0.065 | “True” A−T + Aβ42/40 ≥0.065 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Patients number | 67 | 50 | na |

| Women (%) | 46 (68.7%) | 29 (58.0%) | .23 |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 69.6 ± 8.4 | 67.6 ± 8.2 | .20 |

| MMSE (mean ± SD) | 22.1 ± 5.9 | 22.9 ± 5.2 | .55 |

| Clinical diagnosis before LP | |||

| AD | 58 (86.6%) | 20 (40.0%) | <.0001 |

| Typical amnestic presentations | 42 (72.4%) | 6 (30.0%) | .0008 |

| FTLD spectrum | 4 (6.0%) | 24 (48.0%) | <.0001 |

| Probable bv-FTD | 0 | 8 | |

| Possible bv-FTD | 1 | 1 | |

| sv-PPA | 1 | 10 | |

| CBS, PSPS, apraxia of speech | 2 | 4 | |

| PPA | 0 | 1 | |

| Other (LBD, VCI, psychiatric, MCI or dementia without etiology, etc.) | 5 (7.5%) | 6 (12.0%) | 1 |

| CSF biomarkers (mean ± SD) | |||

| Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 978.3 ± 216.8 | 1313.3 ± 329.1 | <.001 |

| Aβ40 (pg/mL) | 20,334.1 ± 4972.4 | 15,367.5 ± 4091.0 | <.001 |

| T-tau (pg/mL) | 739.9 ± 405.6 | 475.2 ± 147.1 | <.001 |

| Tau181P (pg/mL) | 102.4 ± 37.6 | 74.4 ± 12.3 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; bv-FTLD, behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CBS, corticobasal syndrome; SD, standard deviation; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; LBD, Lewy body disease; LP, lumbar puncture; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; PSPS, progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome; VCI, vascular cognitive impairment.

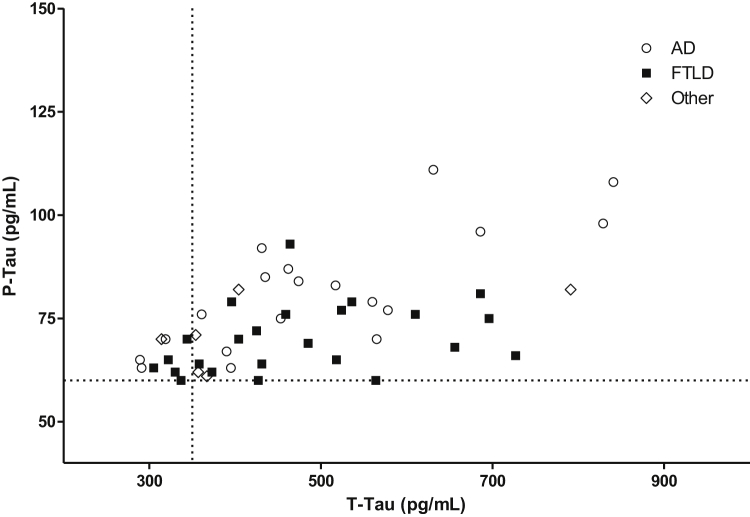

Tau181P and T-tau were significantly higher in the “false” (102.4 ± 37.6 and 739.9 ± 405.6) than in the “true” A−T+ group (74.4 ± 12.3 and 475.2 ± 147.1; P < .001 and P < .001). The proportion of patients with concomitant pathological values of T-tau and tau181P was higher in the “false” (94.0%) than in the “true” A−T+ group (80.0%; P = .02). Yet in the “true” A−T+ group, tau181P and T-tau levels were far beyond cutoff for a majority of patients (Fig. 2). All results remained highly significant after including the study site as a covariate.

Fig. 2.

CSF T-tau and tau181P values in “true” A−T+ patients. Patients diagnosed with AD before the CSF analysis are represented with white circles, patients diagnosed with FTLD with black squares, and others with white diamonds. The vertical dotted line shows the T-tau cutoff (350 pg/mL), and the horizontal dotted line the tau181P cutoff (60 pg/mL). Tau181P and T-tau levels were beyond cutoffs for a majority of patients. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

3.3. Clinical diagnoses before biomarkers analysis in “true” and “false” A−T+ patients

A systematic comparison of the clinical data between “true” and “false” A−T+ groups was performed. There was no significant difference regarding age, gender, and MMSE scores (Table 1).

Diagnoses made by the clinician before CSF biomarkers results were differently distributed between groups (P < .001). AD diagnosis was significantly more frequent in the “false” A−T+ (n = 58, 86.6%) than in the “true” A−T+ group (n = 20, 40.0%; P < .0001). Among the suspected AD diagnoses, typical amnestic presentations were more frequent among “false” A−T+ patients (n = 42, 72.4% of AD diagnoses) than in “true” A−T+ patients (n = 6, 30.0% of AD diagnoses; P = .0008).

Diagnoses of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) spectrum encompass bvFTD, nonfluent/agrammatic and semantic variants of PPA, CBS, and PSPS [42]. FTLD diagnoses were made for only four patients (6.0%) in the “false” A−T+ group, as opposed to 24 patients in the “true” A−T+ group (48.0%, P < .0001). Semantic variant PPA was the leading syndrome (10/24, 41.7%) followed by probable bvFTD (8/24, 33.3%). Four more patients had a clinical presentation consistent with a pure tauopathy (one with CBS, one with PSPS, two with apraxia of speech, and one with nonfluent/agrammatic PPA). The two remaining patients were classified as possible bvFTD and unclassifiable PPA.

Other etiologies (Lewy body disease, multidomain and executive MCI, VCI, psychiatric) were rarer and were not more represented in the “true” than in the “false” A−T+ group (P = 1). Finally, the comparisons of clinical diagnoses remained significant after including the study site as a covariate.

3.4. Follow-up of patients with A−T+ profiles

In the “false” A−T+ group, 58/67 patients (87%) were diagnosed with AD before the LP, and the diagnosis did not change afterward for 50/58 patients (86%). Five of the nine remaining “false” A−T+ patients were diagnosed with AD during follow-up.

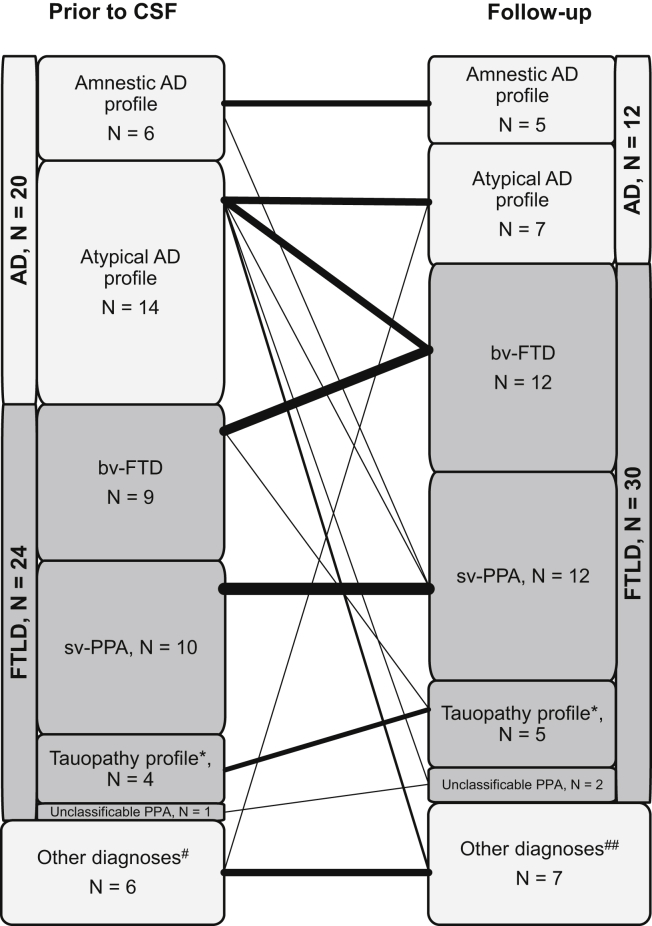

Among the 20/50 patients in the “true” A−T+ group diagnosed with AD before biomarker analysis, 7/20 patients fulfilled criteria for FTLD at follow-up (one with possible bvFTD, three with probable bvFTD, two with semantic PPA, and one with unclassifiable PPA). Among the 24/50 patients from the “true” A−T+ group diagnosed with FTLD before biomarker analysis, there was no change in diagnosis at follow-up (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). In addition, two patients were found to bear a C9ORF72 gene mutation during follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Diagnoses in “true” A−T+ patients before CSF analysis and at follow-up (last diagnosis). *Tauopathy profiles: corticobasal/progressive supranuclear palsy syndromes, speech apraxia, nonfluent agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. #Other diagnoses before CSF analysis: one vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), one Lewy body disease (LBD), one psychiatric disease, two mild cognitive impairments (MCIs), one unclassifiable dementia. ##Other diagnoses at follow-up: three VCI, one LBD, one psychiatric disease, one MCI, one unclassifiable dementia. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; bv-FTD, behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; sv-PPA, semantic variant of PPA.

Overall, 31/50 (62.0%) “true” A−T+ patients had a clinical diagnosis belonging to the FTLD spectrum after reviewing the clinical files: 12/31 fulfilled the clinical criteria for bvFTD (three possible bvFTD, seven probable bvFTD, two genetically confirmed bvFTD) and 19/31 for one of the FTLD variants (12 svPPA, two unclassifiable PPA, 5 PSP/CBS/nfPPA) (Supplementary Table 1).

4. Discussion

The main results of this retrospective multicenter study are that (1) in a real-life memory clinic setting, A−T+ patients defined by CSF Aβ42 were common; (2) the Aβ42/40 ratio used instead of Aβ42 was able to reclassify half of A−T+ patients (i.e., “false” A−T+ patients) into the A+T+ group; (3) the clinical phenotype of “true” A−T+ patients differed from the one of “false” A−T+ patients, with an overrepresentation of patients whose clinical presentation is congruent with FTLD.

Ever since the first report of its use in 1998 [43], the Aβ42/40 ratio was repetitively shown to be superior to Aβ42 for AD diagnosis [37], [38], including at the prodromal stage [29], as well as for differential dementia diagnosis [30], [31], [44], [45]. In the present study, we showed that the Aβ42/40 ratio changes half of previously considered “uninformative” CSF profiles into A+T+, the biological definition of AD [16]. This result is strikingly similar to the ones of previous studies [33], [34], [46].

Although the new NIA-AA criteria recently took the leap to a biomarker-based diagnosis of AD, which renders the clinical correlations accessory, our clinical data support the surrogate use of the Aβ42/40 ratio. We used a reverse approach, classifying T+ patients into three categories according to CSF Aβ42 and the Aβ42/40 ratio, and secondarily tested the classification's relevance. Previous studies have used this reverse “CSF-to-phenotype” approach, although to our knowledge none used the Aβ42/40 ratio [21], [22], [24]. We herein showed that contrary to “true” A−T+ patients, most “false” A−T+ patients with abnormal Aβ42/40 ratios fulfill clinical criteria for amnestic or nonamnestic AD at follow-up.

The case of the “true” A−T + CSF profiles remains an outstanding issue. Considering that CSF tau181P is the most specific marker of AD [12], [13], [14], [47] opens up two possibilities: (1) despite negative amyloid pathology biomarkers, “true” A−T+ cases belong to the AD spectrum or (2) despite positive tau pathology biomarkers, “true” A−T+ cases are non-Alzheimer's pathologies.

The first hypothesis raises the possibility of false-negative amyloid biomarkers. However, it seems unlikely that two consecutive—although not independent—amyloid biomarkers, namely Aβ42 and the Aβ42/40 ratio, yield false-negative results in so many cases. Moreover, the Aβ42/40 ratio was shown to have an excellent negative predictive value against amyloid PET status [48]. Alternatively, “true” A−T+ patients may have AD-type tau pathology while displaying few or no amyloid pathology. This situation has been described in young individuals without any cognitive impairment [49] as well in the primary age-related tauopathy (PART) of older individuals [47]. PART is associated with mild episodic and semantic memory impairment as well as attention and executive deficits [50], a phenotype that corresponds only to a minority of our “true” A−T+ patients. The status of CSF tau biomarkers in PART is currently unknown, and whether PART belongs to the AD spectrum is also a matter of intense debate [49], [50].

The second hypothesis raises the possibility of false-positive tau181P results. However, most “true” A−T+ patients had frankly pathological CSF tau181P levels and a concomitant elevation of CSF T-tau, supporting a genuine positivity of tau pathology biomarkers.

Alternatively, “true” A−T+ cases may be non-AD pathologies with positive tau pathology biomarkers. Interestingly 24/50 “true” A−T+ had a clinical phenotype consistent with FTLD before the LP. Among them, nine patients fulfilled bvFTD criteria and four patients had a PSP/CBD phenotype. It would be tempting to assume that such patients correspond to FTLD with neuroglial tau pathology (FTLD-tau) [51]. Consistently in a recent clinicopathological correlation study, CSF tau181P levels were shown to be positively associated with cerebral tau burden in FTLD, even after exclusion of cases with concomitant AD pathology [52]. However, the other phenotypes in our study (e.g., semantic dementia, n = 10) were suggestive of TDP-43 pathology [53], which was proven in the two cases that bore C9ORF72 mutations.

In line with the latter, surprising results came from clinical cohorts of patients with C9ORF72 mutations and available AD CSF biomarkers [54], as well as from clinical cohorts of putative young-onset AD that had a systematic C9ORF72 mutation screening [55]. Both studies showed that Aβ42 and/or tau181P can be abnormal in a subset of patients bearing C9ORF72 mutations. Concomitant AD pathology is a possible explanation, although the young age of onset and negative amyloid markers of our “true” A−T+ cases make it unlikely. Overall, although we do not discard that some “true” A−T+ patients may be due to false-negative amyloid biomarkers or false-positive tau biomarkers, most “true” A−T+ cases probably correspond to FTLD (and possibly PART) cases, suggesting that some FTLDs are associated with elevated tau biomarkers.

In a broader perspective, “true” A−T+ cases belong to the SNAPs, a concept forged in 2012 to designate A−T+ and/or N+ cases, that is, cases with positive tau biomarkers and/or neurodegeneration markers in neuroimaging (atrophy and/or hypometabolism) [27], [56]. SNAP is not a rare finding in healthy elderly individuals, representing up to 25% of the population, and the relevance of this finding is questionable since SNAP profile does not seem to be associated with cognitive decline [57]. In the population with cognitive decline, the SNAP group is heterogeneous, encompassing cerebrovascular disease, Lewy-body dementia, argyrophilic grain disease, and FTLD or nonspecific hippocampal sclerosis [58]. Within SNAP cases, few studies distinguished A−T+N+ from A+T-N+. A recent survey from a large AD biomarker database showed that 64% of A−N+ cases were T+ [59]. However, this study used high T-tau to define N+, leaving out N+ patients determined by neuroimaging (where atrophy and/or hypometabolism define N+). Furthermore, the Aβ42/40 ratio was not used, which overestimates the number of A−T+N+ cases. Altogether, A−T+N+ probably represents a minority of SNAP cases. We show that identification of T+ cases in SNAP is relevant from a clinical point of view because most of them may correspond to FTLD.

The two main limitations of the study are the retrospective methodology and the lack of pathological confirmation of the diagnoses. These limitations however do not outweigh the main interest of this multicenteric study, resting in its observational nature. Patients included come from daily care practices, patient groups were established and analyzed in an unbiased way, and the main analysis was based on diagnoses made before the LP. If confirmed by further studies, our results will be easy to generalize to the general population of memory clinic patients. Even if we cannot provide proof that “true” A−T+ cases are underlain by FTLD pathology, patient follow-up (and in a few cases genetics) strengthened or confirmed the diagnosis made before the CSF biomarker results.

The third limitation of this study lies in the use of what could appear as arbitrary thresholds to define biomarker positivity, raising the possibility that more stringent thresholds would have yielded very different results. This limitation is shared by all biomarker studies. However, the thresholds we used were defined by multicenter harmonization studies [34], [41]. While we do not deny that some of our cases may correspond to false-positive tau181P results, tau181P was clearly in the pathological range for most patients and associated with elevated T-tau. Furthermore, the rather homogeneous phenotype of “true” A−T+ patients comforts the relevance of our results.

Finally, the changes in clinical diagnoses following biomarker analysis should be considered with caution because CSF results may influence clinicians, raising a risk of circular reasoning. This is particularly true in the “false” A−T+ group, where pathological Aβ42/40 results may have influenced the clinician toward an AD diagnosis. For this reason, our study primarily focused on diagnoses made before the LP. However, changes in diagnoses following biomarker results in the “true” A−T+ group are of particular interest. First, this situation, deemed uninformative in the 2011 criteria, is equivalent to an absence of biomarkers for most clinicians. Second, although the clinician was possibly influenced toward a non-AD diagnosis, the nature of the diagnosis still holds interest.

Overall, our results suggest the Aβ42/40 ratio should be systematically calculated in case of discrepancy between normal CSF Aβ42 (A−) and high CSF tau181P (T+) because it will reclassify half of cases as A+T+. FTLD is probably the leading cause of A−T+ profiles when defined by the Aβ42/40 ratio, and FTLD should be considered in all SNAP cases.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The 2018 National Institute of Aging–Alzheimer's Association research framework has validated the Aβ42/40 ratio as a surrogate marker of amyloid pathology, which reduces the number of patients with A−T+ profiles. However, the proportion and clinical characterization of T+N+ patients with normal Aβ42 in memory clinics remains poorly studied.

-

2.

Interpretation: In this retrospective multicenter study, we show that the Aβ42/40 ratio halves the number of A−T+ patients. “False” A−T+ patients with normal Aβ42 yet abnormal Aβ42/40 had higher cerebrospinal fluid tau181P levels and most had a clinical profile congruent with Alzheimer's disease. In sharp contrast, frontotemporal lobar degeneration phenotypes are overrepresented in “true” A−T+ patients.

-

3.

Future directions: Our study supports the systematic use of the Aβ42/40 ratio in T+N+ cases with normal Aβ42. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration should be systematically discussed in “true” A−T+ cases.

Acknowledgments

This work is the end-of-study dissertation of HPC and TBN for the DIU MA2 course. The DIU MA2 course (Diplôme InterUniversitaire de diagnostic et de prise en charge des Maladies d’Alzheimer et Apparentées) is a National transdisciplinary course on diagnosis and care of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders (www.diu-ma2.fr). The course is supported by the Fondation Alzheimer and the Fondation Vaincre Alzheimer.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2019.01.001.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Troussière A.-C., Wallon D., Mouton-Liger F., Yatimi R., Robert P., Hugon J. Who needs cerebrospinal biomarkers? A national survey in clinical practice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:857–861. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mouton-Liger F., Wallon D., Troussière A.-C., Yatimi R., Dumurgier J., Magnin E. Impact of cerebro-spinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease in clinical practice: a multicentric study. J Neurol. 2014;261:144–151. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blennow K., Zetterberg H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: current status and prospects for the future. J Intern Med. 2018;56:673. doi: 10.1111/joim.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strozyk D., Blennow K., White L.R., Launer L.J. CSF Abeta 42 levels correlate with amyloid-neuropathology in a population-based autopsy study. Neurology. 2003;60:652–656. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000046581.81650.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagan A.M., Mintun M.A., Mach R.H., Lee S.-Y., Dence C.S., Shah A.R. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ 42in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tapiola T., Alafuzoff I., Herukka S.-K., Parkkinen L., Hartikainen P., Soininen H. Cerebrospinal fluid {beta}-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:382–389. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buerger K., Ewers M., Pirttilä T., Zinkowski R., Alafuzoff I., Teipel S.J. CSF phosphorylated tau protein correlates with neocortical neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2006;129:3035–3041. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson O. 18F-AV-1451 and CSF T-tau and P-tau as biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1212–1223. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201707809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otto M., Wiltfang J., Tumani H., Zerr I., Lantsch M., Kornhuber J. Elevated levels of tau-protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurosci Lett. 1997;225:210–212. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesse C., Rosengren L., Andreasen N., Davidsson P., Vanderstichele H., Vanmechelen E. Transient increase in total tau but not phospho-tau in human cerebrospinal fluid after acute stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neselius S., Brisby H., Theodorsson A., Blennow K., Zetterberg H., Marcusson J. CSF-biomarkers in Olympic boxing: diagnosis and effects of repetitive head trauma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderstichele H., De Vreese K., Blennow K., Andreasen N., Sindic C., Ivanoiu A. Analytical performance and clinical utility of the INNOTEST PHOSPHO-TAU181P assay for discrimination between Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:1472–1480. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koopman K., Le Bastard N., Martin J.-J., Nagels G., De Deyn P.P., Engelborghs S. Improved discrimination of autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer's disease (AD) from non-AD dementias using CSF P-tau(181P) Neurochem Int. 2009;55:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoonenboom N.S.M., Reesink F.E., Verwey N.A., Kester M.I., Teunissen C.E., van de Ven P.M. Cerebrospinal fluid markers for differential dementia diagnosis in a large memory clinic cohort. Neurology. 2012;78:47–54. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823ed0f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumurgier J., Vercruysse O., Paquet C., Bombois S., Chaulet C., Laplanche J.-L. Intersite variability of CSF Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in clinical setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jack C.R., Bennett D.A., Blennow K., Carrillo M.C., Dunn B., Haeberlein S.B. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jack C.R., Bennett D.A., Blennow K., Carrillo M.C., Feldman H.H., Frisoni G.B. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87:539–547. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jack C.R., Knopman D.S., Jagust W.J., Petersen R.C., Weiner M.W., Aisen P.S. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansson O., Zetterberg H., Buchhave P., Londos E., Blennow K., Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer's disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:228–234. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchhave P., Minthon L., Zetterberg H., Wallin A.K., Blennow K., Hansson O. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of β-amyloid 1-42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:98–106. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iqbal K., Flory M., Khatoon S., Soininen H., Pirttilä T., Lehtovirta M. Subgroups of Alzheimer's disease based on cerebrospinal fluid molecular markers. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:748–757. doi: 10.1002/ana.20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonell A., Fortea J., Rami L., Bosch B., Balasa M., Sanchez-Valle R. Different profiles of Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in controls and subjects with subjective memory complaints. J Neural Transm. 2010;118:259–262. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okonkwo O.C., Alosco M.L., Griffith H.R., Mielke M.M., Shaw L.M., Trojanowski J.Q. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities and rate of decline in everyday function across the dementia spectrum: normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:688–696. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okonkwo O.C., Mielke M.M., Griffith H.R., Moghekar A.R., O'Brien R.J., Shaw L.M. Cerebrospinal fluid profiles and prospective course and outcome in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:113–119. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albert M.S., Dekosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jack C.R., Jr., Knopman D.S., Weigand S.D., Wiste H.J., Vemuri P., Lowe V. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:765–775. doi: 10.1002/ana.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiltfang J., Esselmann H., Bibl M., Hüll M., Hampel H., Kessler H. Amyloid beta peptide ratio 42/40 but not A beta 42 correlates with phospho-Tau in patients with low- and high-CSF A beta 40 load. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1053–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansson O., Zetterberg H., Buchhave P., Andreasson U., Londos E., Minthon L. Prediction of Alzheimer's disease using the CSF Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23:316–320. doi: 10.1159/000100926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spies P.E., Slats D., Sjögren J.M.C., Kremer B.P.H., Verhey F.R.J., Rikkert M.G.M.O. The cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta42/40 ratio in the differentiation of Alzheimer's disease from non-Alzheimer's dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:470–476. doi: 10.2174/156720510791383796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slaets S., De Deyn P.P. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ1-40 improves differential dementia diagnosis in patients with intermediate P-tau181P levels. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:759–767. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaufils E., Dufour-Rainfray D., Hommet C., Brault F., Cottier J.-P., Ribeiro M.-J. Confirmation of the amyloidogenic process in posterior cortical atrophy: value of the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:775–780. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauvée M., DidierLaurent G., Latarche C., Escanyé M.-C., Olivier J.-L., Malaplate-Armand C. Additional use of Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers P-tau and Aβ42 increases the level of evidence of Alzheimer's disease pathophysiological process in routine practice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41:377–386. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumurgier J., Schraen S., Gabelle A., Vercruysse O., Bombois S., Laplanche J.-L. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β 42/40 ratio in clinical setting of memory centers: a multicentric study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:30. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sachdev P., Kalaria R., O'Brien J., Skoog I., Alladi S., Black S.E. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:206–218. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rascovsky K., Hodges J.R., Knopman D., Mendez M.F., Kramer J.H., Neuhaus J. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134:2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorno-Tempini M.L., Hillis A.E., Weintraub S., Kertesz A., Mendez M., Cappa S.F. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76:1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKeith I.G., Boeve B.F., Dickson D.W., Halliday G., Taylor J.-P., Weintraub D. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boxer A.L., Yu J.-T., Golbe L.I., Litvan I., Lang A.E., Höglinger G.U. Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: new diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:552–563. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30157-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armstrong M.J., Litvan I., Lang A.E., Bak T.H., Bhatia K.P., Borroni B. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2013;80:496–503. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0fd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehmann S., Schraen S., Quadrio I., Paquet C., Bombois S., Delaby C. Impact of harmonization of collection tubes on Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:S390–S394. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finger E.C. Frontotemporal Dementias. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22:464–489. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shoji M., Matsubara E., Kanai M., Watanabe M., Nakamura T., Tomidokoro Y. Combination assay of CSF tau, A beta 1-40 and A beta 1-42(43) as a biochemical marker of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci. 1998;158:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bibl M., Esselmann H., Lewczuk P., Trenkwalder C., Otto M., Kornhuber J. Combined analysis of CSF Tau, Aβ42, Aβ1–42% and Aβ1–40ox% in Alzheimer's disease, Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Parkinson's Disease Dementia. Int J Alzheimer's Dis. 2010;2010:1–7. doi: 10.4061/2010/761571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nutu M., Londos E., Minthon L., Nägga K., Hansson O. Evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β1-42/amyloid-β1-40 ratio measured by alpha-LISA to distinguish Alzheimer's disease from other dementia disorders. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;36:99–110. doi: 10.1159/000353442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehmann S., Delaby C., Boursier G., Catteau C., Ginestet N., Tiers L. Relevance of Aβ42/40 Ratio for Detection of Alzheimer Disease Pathology in Clinical Routine: The PLMR Scale. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:138. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gabelle A., Dumurgier J., Vercruysse O., Paquet C., Bombois S., Laplanche J.-L. Impact of the 2008-2012 French Alzheimer Plan on the use of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in research memory center: the PLM Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:297–305. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewczuk P., Matzen A., Eusebi P., Morris J.C., Fagan A.M. Cerebrospinal Fluid Aβ42/40 Corresponds Better than Aβ42 to Amyloid. PET Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;55:813–822. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braak H., Del Tredici K. The pathological process underlying Alzheimer's disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jefferson-George K.S., Wolk D.A., Lee E.B., McMillan C.T. Cognitive decline associated with pathological burden in primary age-related tauopathy. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lebouvier T., Pasquier F., Buée L. Update on tauopathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:589–598. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irwin D.J., Lleó A., Xie S.X., McMillan C.T., Wolk D.A., Lee E.B. Ante mortem cerebrospinal fluid tau levels correlate with postmortem tau pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:247–258. doi: 10.1002/ana.24996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Josephs K.A., Hodges J.R., Snowden J.S., Mackenzie I.R., Neumann M., Mann D.M. Neuropathological background of phenotypical variability in frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:137–153. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0839-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kämäläinen A., Herukka S.-K., Hartikainen P., Helisalmi S., Moilanen V., Knuuttila A. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease in patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with the C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;39:287–293. doi: 10.1159/000371704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wallon D., Rovelet-Lecrux A., Deramecourt V., Pariente J., Le Ber I., Pasquier F. Definite behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia with C9ORF72 expansions despite positive Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32:19–22. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jack C.R., Knopman D.S., Chételat G., Dickson D., Fagan A.M., Frisoni G.B. Suspected non-Alzheimer disease pathophysiology--concept and controversy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:117–124. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burnham S.C., Bourgeat P., Doré V., Savage G., Brown B., Laws S. Clinical and cognitive trajectories in cognitively healthy elderly individuals with suspected non-Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology (SNAP) or Alzheimer's disease pathology: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis P.R., Jicha G.A., Scheff S.W. Alzheimer's disease is not ‘brain aging’: neuropathological, genetic, and epidemiological human studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:571–587. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0826-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paquet C., Bouaziz-Amar E., Cognat E., Volpe-Gillot L., Haddad V., Mahieux F. Distribution of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profiles in patients explored for cognitive disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:889–897. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.