Abstract

As universal heterodimer partners of many nuclear receptors, the retinoid X receptors (RXRs) constitute key transcription factors. They regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, inflammation, and metabolic homeostasis and have recently been proposed as potential drug targets for neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases. Owing to the hydrophobic nature of RXR ligand binding sites, available synthetic RXR ligands are lipophilic, and their structural diversity is limited. Here, we disclose the computer-assisted discovery of a novel RXR agonist chemotype and its systematic optimization toward potent RXR modulators. We have developed a nanomolar RXR agonist with high selectivity among nuclear receptors and superior physicochemical properties compared to classical rexinoids that appears suitable for in vivo applications and as lead for future RXR-targeting medicinal chemistry.

Keywords: Nuclear receptors, RXR, Neurodegeneration, Inflammation

The fatty acid-sensing ligand-activated transcription factors retinoid X receptors (RXRs, NR2B1–3) stand out among nuclear receptors by acting as universal heterodimer partners of numerous members of this protein family.1 Thereby, RXRs are key regulators of cell proliferation and differentiation and are involved in metabolic homeostasis as well as inflammation.2 The synthetic rexinoid bexarotene (1, Figure 1) and the putative endogenous RXR agonist 9-cis-retinoic acid (2) are the only RXR ligands with market approval and only available for second line treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma, respectively. Recent animal studies have also demonstrated great potential of RXR modulation in neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease.3,4 However, toxicity, lack of selectivity,5 and unfavorable physicochemical properties of available rexinoids hamper the full exploration of RXR’s therapeutic potential.6−10 By pharmacophore-based virtual screening and subsequent structural optimization, we have identified a new RXR agonist chemotype to equip medicinal chemistry with innovative novel rexinoids and potentially overcome the characteristic issues of RXR ligands.

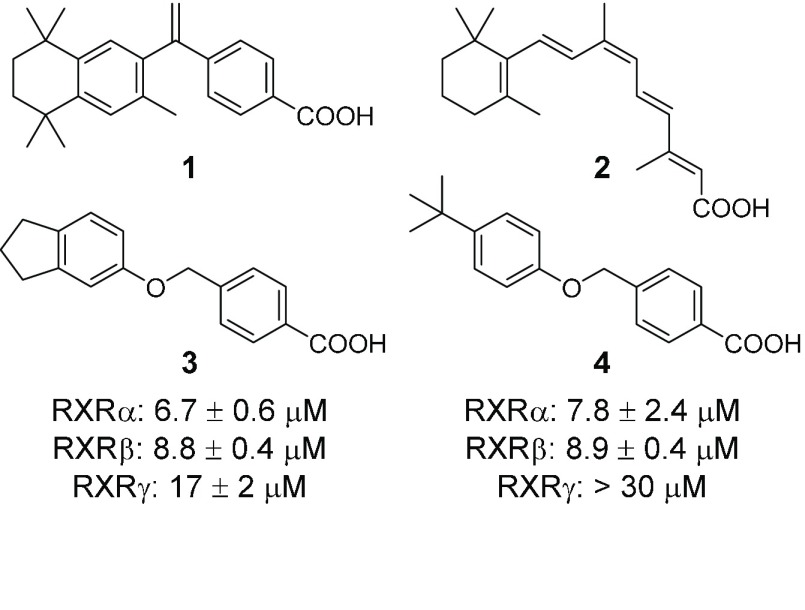

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of bexarotene (1), 9-cis-retinoic acid (2), and virtual screening hits (3 and 4) confirmed active in vitro.

To identify potential RXR ligands in large screening collections, we have developed a pharmacophore model (Figure S1) based on the binding mode of bexarotene (1, PDB entry 4K6I(11)) in the hRXRα ligand binding domain (LBD) considering positive features and excluded volumes. Screening of a focused library of commercially available fatty acid mimetics10 on this computational model resulted in 29 primary hits. The 15 most diverse compounds of these computationally favored molecules (Figure S2) were evaluated in vitro employing specific Gal4-hybrid reporter gene assays to determine modulatory potential on the three RXR subtypes. In these assays, HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids coding for a constitutively expressed (CMV promoter) RXR-LBD-Gal4-DNA binding domain fusion receptor, a Gal4-responsive firefly luciferase, and a constitutively expressed (SV40 promoter) renilla luciferase for normalization. In total, four compounds were confirmed active on RXR at 10 μM (Figure S2) of which two were rejected due to maximal activations below 10% compared to bexarotene (1, 1 μM). Full dose–response characterization of the remaining hits 3 and 4 revealed comparably low micromolar potency on all RXR subtypes (7–18 μM), but 3 possessed markedly higher activation efficacy and was less toxic (Figure S3).

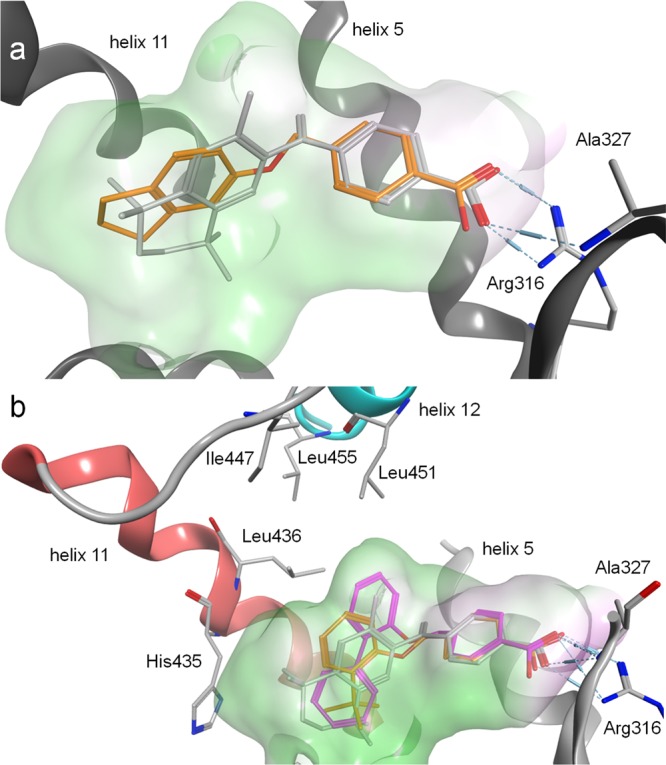

In silico binding mode inspection of 3 (Figure 2a) suggested favorable formation of the canonical neutralizing contact with Arg316 but also indicated considerable space for structural optimization. While the lipophilic moieties of 3 and 1 aligned well, a subpocket close to the methylene group of the crystallized ligand 1 was not occupied by 3 and further space seemed available around the indane residue. For this promising optimization potential and their favorable activity, we systematically studied the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of 3 and 4 as RXR agonists with analogues 5–36.

Figure 2.

Molecular docking of 3, 27, and 28 into the ligand binding domain of RXRα (PDB-ID 4K6I). Crystallized ligand 1 in gray for comparison. Pocket surfaces are colored according to lipophilicity with green for lipophilic and red for hydrophilic. (a) 3 as 1 forms a canonical neutralizing contact with Arg316 but leaves considerable space for optimization. (b) 28 (pink) in contrast to 27 (orange) occupies an unexplored subpocket between helices 5, 11, and 12, which appears essential for stabilizing contacts to helix 12 that result in high activation efficacy.

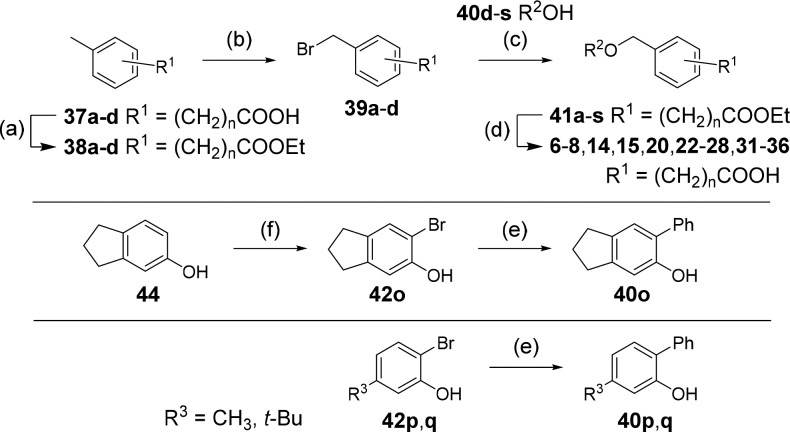

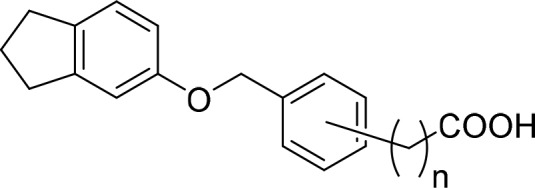

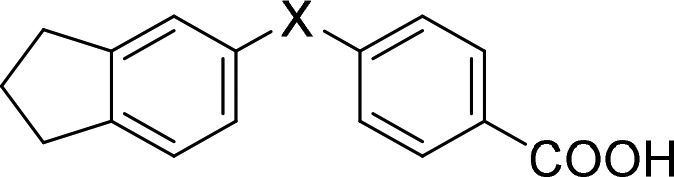

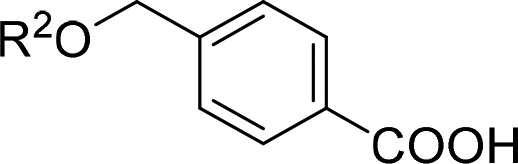

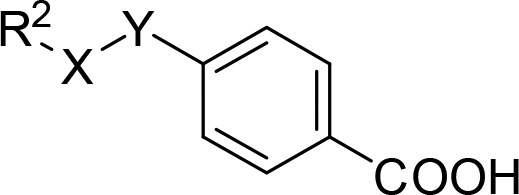

Analogues 3–5, 16–19, 21, and 29 were commercially available. The synthesis of the remaining derivatives was accomplished in three different routes (Scheme 1–3). In route A (Scheme 1), carboxylic acids of different chain lengths with terminal toluene residues (37a–d) were brominated under radical conditions as ethyl esters 38a–d to benzyl bromides 39a–d, which were then suitable for Williamson ether synthesis to esters 41a–s with phenols 40d–s. The required phenols were either purchased or obtained from Suzuki reaction of the corresponding 2-bromophenols (42o-q) with phenylboronic acid (43). Bromination of 5-indanol (44) afforded 6-bromo-5-indanol (42o), whereas the remaining 2-bromophenols (42p,q) were purchased. Alkaline ester hydrolysis of 41a–s then yielded test compounds 6–8, 14, 15, 20, 22–28, and 31–36. 4-Formylbenzoic acid (45) and 5-aminoindane (46) were reacted to 47 by amide coupling and to secondary amine 11 by reductive amination in Route B (Scheme 2). Subsequently, aldehyde 47 was oxidized to carboxylic acid 10, and amine 11 was methylated in an Eschweiler-Clarke reaction affording 12 (Route B).

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route A to Novel RXR Agonists.

Reagents and conditions: (a) EtOH, H2SO4, reflux, 77–99%; (b) NBS, AIBN, CHCl3, reflux, 15–86%; (c) K2CO3, DMF, rt–100 °C, 28–94%; (d) LiOH, THF, H2O, rt–50 °C, 31–99%; (e) Ph-B(OH)2 (43), Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3, dioxane, H2O, reflux, 40–64%; (f) NBS, DMF, rt, 80%. n is defined in Table 1; R2 is defined in Tables 3 and 4.

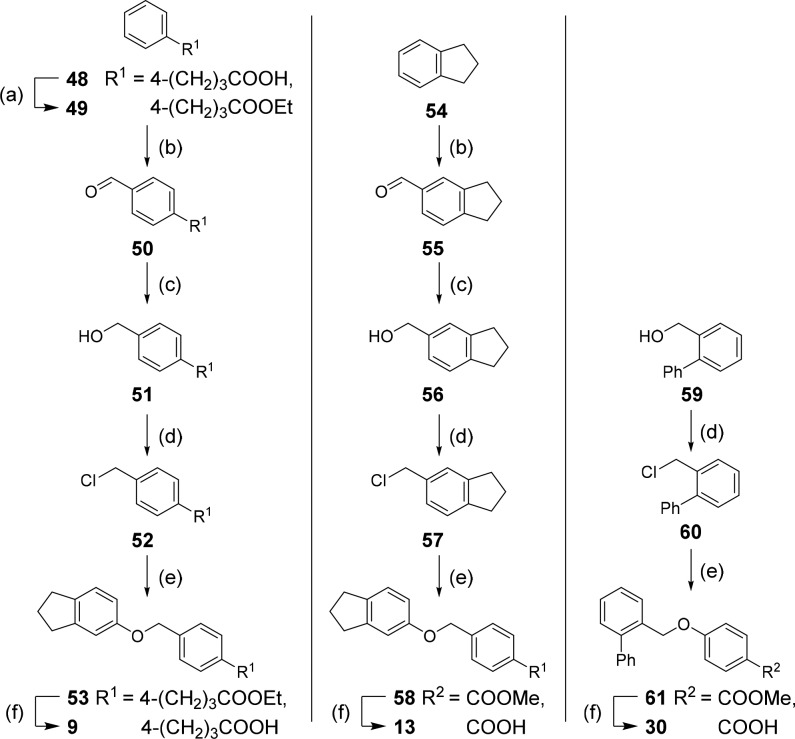

Scheme 3. Synthetic Route C to Novel RXR Agonists.

Reagents and conditions: (a) EtOH, H2SO4, reflux, 96%; (b) hexamethylenetetramine, TFA, 100 °C, 18–60%; (c) NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C → rt, 55–59%; (d) SOCl2, DCM, 0 °C, 41–80%; (e) 5-indanol (44) or methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (62), K2CO3, DMF, rt–100 °C, 82–93%; (f) LiOH, THF, H2O, rt–50 °C, 92–99%.

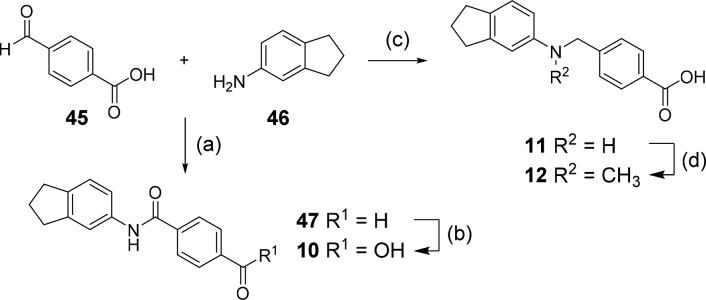

Scheme 2. Synthetic Route B to Novel RXR Agonists.

Ragents and conditions: (a) EDC·HCl, 4-DMAP, CHCl3, reflux, 63%; (b) oxone, DMF, rt, 29%; (c) NaBH(OAc)3, DCE, HOAc, rt, 91%; (d) glacial acetic acid, formaldehyde, reflux, 54%.

For the preparation of 9, 13, and 30 (Route C, Scheme 3), 48 was esterified to 49, and arenes 49 and 54 were formylated in a Duff reaction. The resulting aldehydes (50, 55) were reduced to the corresponding benzyl alcohols 51 and 56. Then 51, 56, and 59 were transformed to benzyl chlorides 52, 57, and 60 and used for Williamson ether synthesis with 5-indanol (44) to 53 or with methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (62) to “inverted” ethers 58 and 61, respectively. Saponification yielded the free carboxylic acids 9, 13, and 30.

For a systematic SAR evaluation, we first studied the favored position and length of the carboxyl side chain (Table 1). 4-Benzoic acid 3 possessed balanced low micromolar potency on RXRs despite lower activation efficacy on RXRγ. Shifting the carboxyl group to the 2-position (6) significantly reduced activity on all three RXR subtypes, and 3-substitution (5) produced a firefly luciferase inhibitor, which rendered 4-substitution as preferred geometry for RXR activation. Exploration of the side chain length in 4-position revealed decreased potency for phenylacetic acid 7, which was restored with phenylpropionic acid 8. On RXRγ, 8 was slightly superior to 3 in terms of activation efficacy (19%). Further chain elongation to 9 resulted in toxicity.

Table 1. Lead Optimization in the Acidic Head Region.

| no. | pos. | n | RXRα EC50 [μM] | RXRβ EC50 [μM] | RXRγ EC50 [μM] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 0 | 6.7 ± 0.6 (29 ± 3%) | 8.8 ± 0.4 (28 ± 1%) | 17 ± 2 (5.0 ± 0.2%) |

| 5 | 3 | 0 | -1 | -1 | -1 |

| 6 | 2 | 0 | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| 7 | 4 | 1 | 13 ± 2 (47 ± 5%) | 18 ± 1 (9.9 ± 0.1%) | 22 ± 1 (8.8 ± 0.1%) |

| 8 | 4 | 2 | 6.7 ± 0.5 (28 ± 1%) | 10 ± 1 (29 ± 2%) | 21 ± 1 (19 ± 1%) |

| 9 | 4 | 3 | tox. | tox. | tox. |

Firefly luciferase inhibitor; tox., toxic at 30 μM; pos., position; relative activation efficacy compared to 1 (1 μM) is shown in parentheses. All values are the mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3.

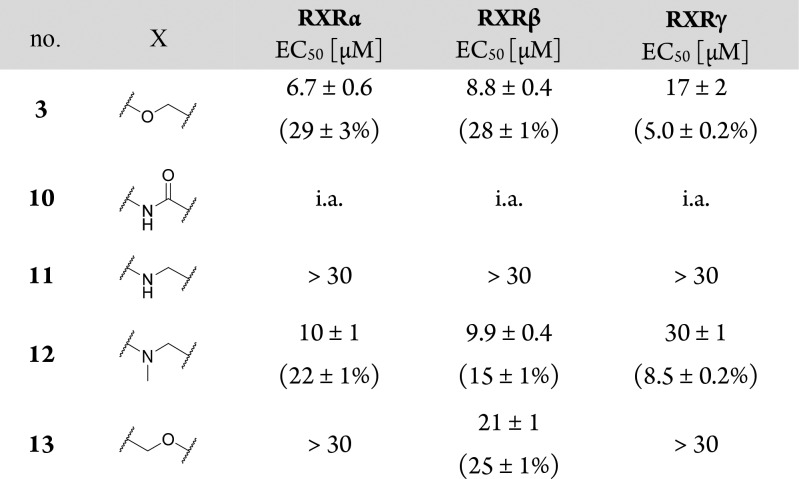

In the linker region (Table 2), ether replacement by an amide moiety (10) was not tolerated, and free amine 11 revealed markedly reduced potency. N-Methylamine 12 recovered the potency of ether 3 in terms of EC50 values but with diminished activation efficacy. Inverted ether 13 was active but turned out too toxic for full characterization. Still, reduced potency of 13 indicated that the linker residue of 3 was superior.

Table 2. Structure–Activity Relationship of Linker Moiety1.

i.a., inactive at 30 μM; relative activation efficacy compared to 1 (1 μM) is shown in parentheses. All values are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3.

To systematically study the SAR of the lipophilic ether substituent, we started with the minimized motif 14 (Table 3) only carrying an unsubstituted phenyl ether, which still activated all RXRs with lower potency. Introduction of halogen substituents in 4-position (15–17) enhanced potency with increasing halogen size. Similar SAR was observed for 4-alkyl derivatives where potency increased from ethyl (18) over iso-propyl (19) to tert-butyl (4). However, all 4-substituents, especially alkyl residues, markedly decreased activation efficacy and were less potent on RXRγ. When we shifted the chlorine substituent from 4- (15) to 3-position (20), potency and activation efficacy were improved, but the highest activity was achieved with a 2-chlorine substituent (21). Further exploration of substituents in 2-position revealed that fluorine (22) was not favored, but small lipophilic residues such as methyl (23) and especially trifluoromethyl (24) markedly increased potency. A similar trend was observed for methoxy (25) and trifluoromethoxy (26) derivatives, where 26 demonstrated balanced high potency and efficacy on all RXRs. Further improvement was achieved with larger residues in 2-position with tert-butyl (27) and phenyl (28) analogues displaying nanomolar activity. While 27 despite high potency possessed weak activation efficacy, 2-phenyl derivative 28 was identified as RXR agonist with particularly high efficacy in RXRγ activation. This trend was not observed for any other compound in this series rendering 28 as potential starting point for the development of RXRγ-preferential ligands.

Table 3. Modification in the Lipophilic Tail Region1.

| no. | R2 | RXRα EC50 [μM] | RXRβ EC50 [μM] | RXRγ EC50 [μM] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | Ph | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| 15 | 4-Cl-Ph | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| 16 | 4-Br-Ph | 40 ± 4 (21 ± 4%) | 48 ± 10 (36 ± 15%) | >30 |

| 17 | 4-I-Ph | 24 ± 1 (19 ± 1%) | 29 ± 2 (25 ± 2%) | >30 |

| 18 | 4-Et-Ph | 28 ± 3 (11 ± 1%) | 35 ± 3 (7.4 ± 0.7%) | i.a. |

| 19 | 4-iPr-Ph | 16 ± 1 (11 ± 1%) | 16 ± 1 (9.5 ± 0.5%) | i.a. |

| 4 | 4-tBu-Ph | 7.8 ± 2.4 (16 ± 4%) | 8.9 ± 0.4 (15 ± 1%) | >30 |

| 20 | 3-Cl-Ph | 17 ± 1 (54 ± 3%) | 20 ± 4 (26 ± 5%) | 44 ± 16 (9.3 ± 3.4%) |

| 21 | 2-Cl-Ph | 9.9 ± 0.5 (58 ± 2%) | 8.3 ± 0.8 (31 ± 2%) | >30 |

| 22 | 2-F-Ph | >30 | >30 | >30 |

| 23 | 2-CH3-Ph | 5.0 ± 0.1 (24 ± 1%) | 8.6 ± 1.1 (27 ± 2%) | 19 ± 1 (19 ± 1%) |

| 24 | 2-CF3-Ph | 1.1 ± 0.1 (22 ± 1%) | 2.1 ± 0.1 (22 ± 1%) | 10 ± 1 (52 ± 1%) |

| 25 | 2-OCH3-Ph | 29 ± 1 (21 ± 1%) | >30 | >30 |

| 26 | 2-OCF3-Ph | 1.1 ± 0.1 (26 ± 1%) | 1.9 ± 0.1 (18 ± 1%) | 4.2 ± 0.1 (25 ± 1%) |

| 27 | 2-tBu-Ph | 0.16 ± 0.01 (11 ± 1%) | 0.37 ± 0.03 (12 ± 1%) | 1.1 ± 0.1 (21 ± 1%) |

| 28 | (1,1′-biphenyl)-2-yl | 0.28 ± 0.01 (70 ± 1%) | 0.31 ± 0.01 (44 ± 1%) | 1.6 ± 0.1 (94 ± 4%) |

i.a., inactive at 30 μM; relative activation efficacy compared to 1 (1 μM) is shown in parentheses. All values are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3.

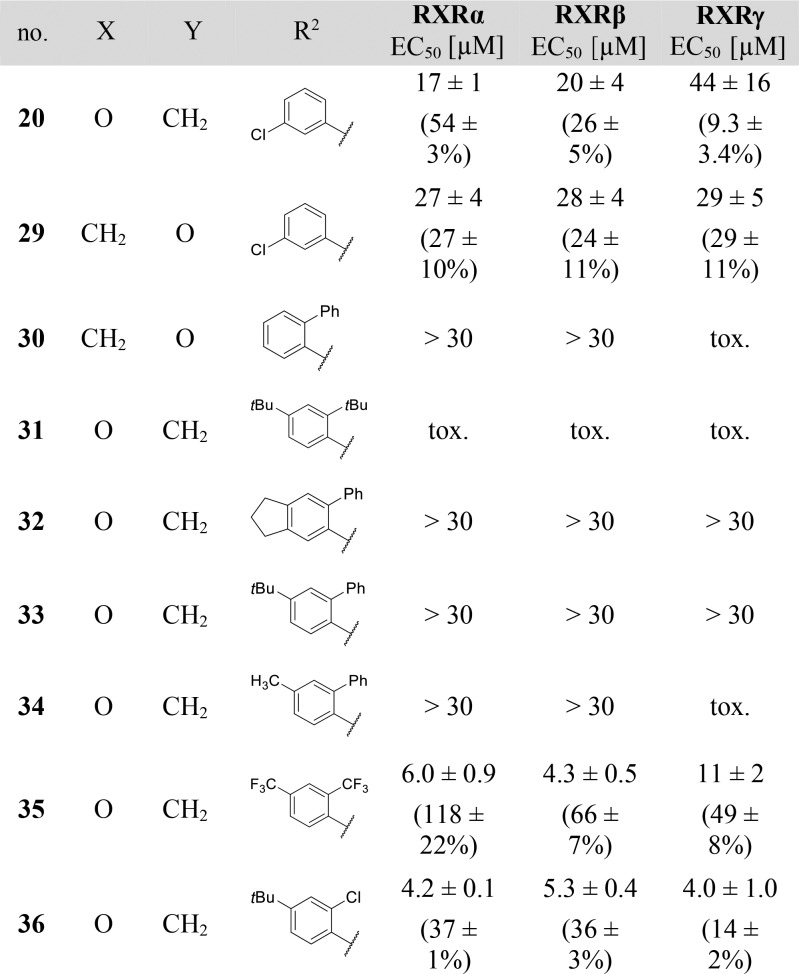

Systematic analysis of the SAR for the individual molecular building blocks of 3 and derivatives particularly suggested optimization potential in the lipophilic ether substituent. Striving to combine the SAR knowledge for further optimization, we fused the most promising structural elements identified for each moiety of the lead compound (Table 4).

Table 4. Combinations of Structural Motifs for Enhanced Potency Identified in SAR Studies1.

tox., toxic at 30 μM; relative activation efficacy compared to 1 (1 μM) is shown in parentheses. All values are mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3.

First, we aimed to enhance the RXRγ-preferential profile of 28 by inverting the linker residue since 3-chlorine-substituted inverted ether 29 improved balance over all RXR subtypes in terms of potency and activation efficacy. However, the resulting compound 30 turned out less potent and toxic. We then combined bulky, hydrophobic elements in 2- and 4-position of the phenyl ether since both positions were favored for high potency (e.g., 4 and 28). 2,4-Di-tert-butyl derivative 31, 6-phenylindane 32, 4-tert-butyl-2-phenyl combination 33, and 4-methyl-2-phenyl analogue 34 failed to achieve any additive effect in potency, however, and were significantly less active than 28. We hypothesized that steric reasons might explain the inactivity of these bulky combinations and investigated sterically less demanding combinations in the hydrophobic tail region with 2,4-bis(trifluoromethyl) derivative 35 and 4-tert-butyl-2-chloro residue 36. Both molecules did not achieve as high potency as 28, but 35 provided full-agonistic activity on RXRα as well as increased maximal activation of RXRβ compared to single trifluoromethyl substitution in 2-position (24).

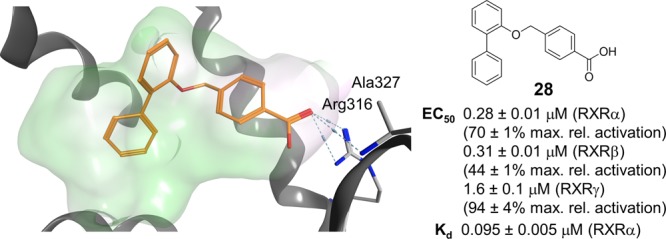

In an attempt to rationalize the high potency of 28 and its rather strict SAR that prevented any further optimization on the phenylether moiety, we virtually studied its interaction with the RXRα ligand binding site compared to bexarotene (1, Figure 2b). The benzoic acid residues of 1 and 28 aligned well in the proposed binding mode and participated in the canonical neutralizing contact with Arg316. The lipophilic tails of 1 and 28 differently extended to the large lipophilic pocket of RXRα and deep burial of the central aromatic ring of 28 in a subpocket between helices 5 and 11 illustrated why no further substituents were tolerated on this ring. Instead, the calculated binding mode indicated further optimization potential at the terminal aromatic ring. Similar to previous observations,12,13 the molecular docking simulation suggested that lack of direct interaction with helix 12 may explain lower activation efficacy of 27 compared to 1 and 28. As a result of the bulkier 2-phenyl substituent, the central aromatic ring of 28 extended to a lipophilic subpocket between helices 5, 11, and 12. This region appears not to be addressed by 27 after all and in contrast to 27, the central aromatic ring of 28 provided a lipophilic surface for stabilizing interactions with helix 12 that were mediated by lipophilic contacts to the network of Leu436, Leu451, and Leu455. Overall, the molecular docking suggested a binding mode for 28 that significantly differed from the classical rexinoid 1 since it protruded to unexplored regions of the pocket between helices 5 and 11 and provided a novel binding geometry rendering 28 as innovative new RXR ligand. To further evaluate this novel RXR modulator and its properties, 28 was extensively characterized in vitro (Figure 3).

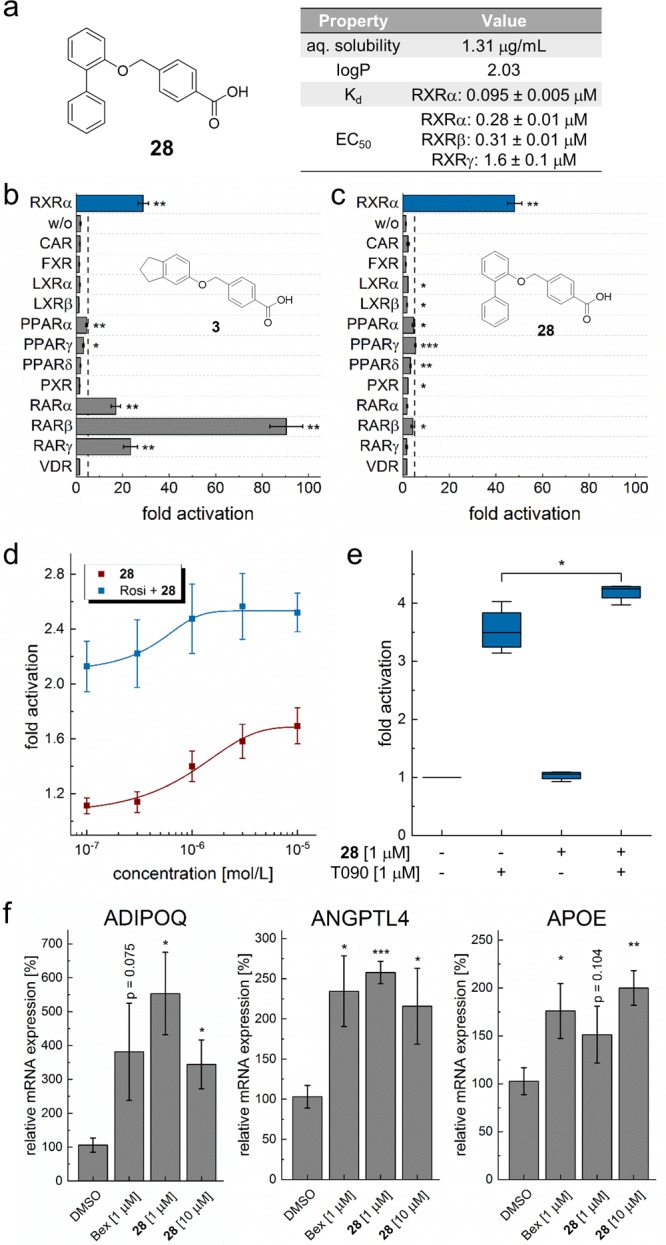

Figure 3.

(a) Structure and key properties of compound 28. (b,c) Selectivity profile of 3 and optimized derivative 28 on 12 nuclear receptors related to RXRs at 30 μM. Although 3 also activates RAR, 28 gained full RXR selectivity. n ≥ 3. (d, e) 28 activated permissive RXR heterodimers with (d) PPAR and (e) LXR in full-length assays showing synergistic effects with the respective partner agonists rosiglitazone (Rosi) and T0901317 (T090); (d) n = 3, (e) n = 4. (f) 28 induced RXR-regulated gene expression (qRT-PCR) of adiponectin (ADIPOQ), angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4), and apolipoprotein E (APOE) with similar efficacy as bexarotene (1, Bex). n = 4. All values are mean ± SEM; ∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗ p < 0.01; ∗∗∗ p < 0.001.

The interaction of 28 and the RXRα LBD was studied under cell-free conditions by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), where 28 displayed high affinity binding with an independent binding constant Kd of 0.095 ± 0.005 μM (Figure S4). Binding was both driven by enthalpic (ΔH = −25 kJ/mol) and entropic shares (ΔS = 49 J/mol K). The minor difference between the Kd and EC50 value may be due to the cellular assay environment where activity is also affected by cell penetration and potential degradation.

Off-target profiling of 28 and the initial screening hit 3 on 12 nuclear receptors in addition to RXRs showed markedly improved selectivity for 28 (Figure 3b,c). While 3 also strongly activated RARs at 30 μM concentration, 28 was only active on RXRs. In addition, 28 possessed favorable properties compared to classical rexinoid 1 with superior aqueous solubility (28, 1.3 μg/mL; 1, 0.31 μg/mL), experimental logP (28, 2.0; 1, 5.2, Figure S5), and cytotoxicity (Figure S3).

To further evaluate the RXR-modulatory activity of 28, we studied its effect on the RXR heterodimers (Figure 3d,e) in reporter gene assays employing human full-length heterodimers to govern reporter gene expression (Figure 3d,e). 28 was capable of activating PPARγ-RXR with an EC50 value of 1.0 ± 0.2 μM and synergistically promoted its activation by PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (1 μM) with an EC50 value of 0.47 ± 0.12 μM. LXR-RXR activation by 28 alone was too weak to reach statistical significance, but 28 again synergistically promoted LXR-RXR activation by LXR agonist T0901317 (1 μM).

As nuclear receptors translate ligand signals into adaptions in gene expression, we also analyzed RXR modulation by 28 on mRNA level (Figure 3f). In HepG2 cells, 28 induced the expression of adiponectin (ADIPOQ), angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4), and apolipoprotein E (APOE), which are known to be regulated by RXRs and their heterodimer partners PPAR and LXR. At 1 μM and 10 μM concentration, 28 induced gene expression with comparable efficacy as bexarotene (1, 1 μM). Thus, 28 was confirmed as potent and selective RXR agonist.

Potential therapeutic applications for RXR modulators are versatile. RXR agonists appear to contribute to β-amyloid clearance in Alzheimer’s disease4 and accelerate central nervous system remyelination in multiple sclerosis.3 Apart from these neurodegenerative diseases, rexinoids also hold potential in cancer where 1 is approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and 2 represents a therapeutic option in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Current research also focuses on other cancer types.6,14 Furthermore, RXR ligands showed beneficial effects in a multitude of disorders linked to the metabolic syndrome such as diabetes15 and cardiovascular diseases.16 However, several side-effects, among them hypertriglyceridemia,16 hepatomegaly,17 and hypothyroidism,18 hinder further exploration of RXRs as therapeutic targets illustrating the high unmet need for novel RXR modulators that can overcome these obstacles.

Here we report the computer-assisted discovery and structural optimization of a new RXR activator chemotype culminating in the development of nanomolar RXR agonist 28. In vitro characterization confirmed high affinity of 28 to the RXR LBD and effective induction of RXR-regulated gene expression by 28. The compound’s reduced lipophilicity, as well as improved solubility and beneficial toxicity profile, is clearly superior to the classical rexinoid 1, which suffers from poor physicochemical properties and pronounced toxicity. Furthermore, recent reports12,13,19 suggest that RXR modulators with partial agonistic activity offer preferable safety compared to full RXR agonists but retain therapeutic efficacy. Thus, the high potency of 28 combined with its intermediate RXR activation efficacy constitutes a very favorable pharmacodynamic profile.

Molecular docking of 28 to the RXRα LBD suggested a significantly different binding mode for 28 compared to 1, which might enable this new RXR ligand scaffold to overcome the characteristic challenge of poor subtype selectivity in RXR targeting. Especially the slight RXRγ-favoring activity of 28 in terms of activation efficacy appears promising and might open a new avenue toward subtype selectivity. Despite its high RXR-agonistic potency, 28 has a small, rather fragment-like size (304 g/mol) and a modular architecture that will allow broad further structural variation. Therefore, the new RXR ligand scaffold of 28 contributes to the SAR of RXR modulators and can provide access to innovative RXR activators that help further explore the therapeutic potential of RXR modulation in neurodegeneration, inflammation, and cancer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the DFG (PR1405/2-2, SFB1039/A07). P.H. was supported by the Else-Kroener-Fresenius-Foundation funding the graduate school ‘Translational Research Innovation – Pharma’ (TRIP). E.P. was supported by the DFG (PR1405/4-1).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADIPOQ

adiponectin

- AIBN

azobis(isobutyronitrile)

- ANGPTL4

angiopoietin-like 4

- APOE

apolipoprotein E

- CAR

constitutive androgen receptor

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- DCE

1,2-dichloroethane

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- EC

effective concentration

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- LXR

liver X receptor

- NBS

N-Bromosuccinimide

- Pos

position

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- rt

room temperature

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00551.

Synthesis and analytical characterization of compounds 6–61, assay protocols, computational methods (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Germain P.; Chambon P.; Eichele G.; Evans R. M.; Lazar M. A.; Leid M.; De Lera A. R.; Lotan R.; Mangelsdorf D. J.; Gronemeyer H. International Union of Pharmacology. LXIII. Retinoid X Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58 (4), 760–772. 10.1124/pr.58.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S.; Kakuta H. Retinoid X Receptor Ligands: A Patent Review (2007 - 2013). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2014, 24 (4), 443–452. 10.1517/13543776.2014.880692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. K.; Jarjour A. A.; Oumesmar B. N.; Kerninon C.; Williams A.; Krezel W.; Kagechika H.; Bauer J.; Zhao C.; Evercooren A. B.-V.; et al. Retinoid X Receptor Gamma Signaling Accelerates CNS Remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14 (1), 45–53. 10.1038/nn.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. E.; Cirrito J. R.; Wesson D. W.; Lee C. Y. D.; Karlo J. C.; Zinn A. E.; Casali B. T.; Restivo J. L.; Goebel W. D.; James M. J.; et al. ApoE-Directed Therapeutics Rapidly Clear β-Amyloid and Reverse Deficits in AD Mouse Models. Science 2012, 335 (6075), 1503–1506. 10.1126/science.1217697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitel P.; Achenbach J.; Moser D.; Proschak E.; Merk D. DrugBank Screening Revealed Alitretinoin and Bexarotene as Liver X Receptor Modulators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27 (5), 1193–1198. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liby K.; Sporn M. Rexinoids for Prevention and Treatment of Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17 (6), 721–730. 10.2174/1568026616666160617090702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshagh K.; Romero L. S.; So J. K.; Zhao X. F. Late-Onset Bexarotene-Induced CD4 Lymphopenia in a Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma Patient. Cutis 2017, 99 (2), E30–E34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz B.; de Lera Á. Advances in Drug Design with RXR Modulators. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2012, 7 (11), 1003–1016. 10.1517/17460441.2012.722992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez M.; Alvarez S.; de Lera A. R. Natural and Structure-Based RXR Ligand Scaffolds and Their Functions. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17 (6), 631–662. 10.2174/1568026616666160617072521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proschak E.; Heitel P.; Kalinowsky L.; Merk D. Opportunities and Challenges for Fatty Acid Mimetics in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (13), 5235–5266. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerma L. J.; Xia G.; Qui C.; Cox B. D.; Chalmers M. J.; Smith C. D.; Lobo-Ruppert S.; Griffin P. R.; Muccio D. D.; Renfrow M. B. Defining the Communication between Agonist and Coactivator Binding in the Retinoid X Receptor α Ligand Binding Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289 (2), 814–826. 10.1074/jbc.M113.476861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawata K.; Morishita K.; Nakayama M.; Yamada S.; Kobayashi T.; Furusawa Y.; Arimoto-Kobayashi S.; Oohashi T.; Makishima M.; Naitou H.; et al. RXR Partial Agonist Produced by Side Chain Repositioning of Alkoxy RXR Full Agonist Retains Antitype 2 Diabetes Activity without the Adverse Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (2), 912–926. 10.1021/jm501863r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa F.; Yamada S.; Yakushiji N.; Shinozaki R.; Nakayama M.; Kawata K.; Hagaya M.; Kobayashi T.; Kohara K.; Furusawa Y.; et al. Mechanism of Retinoid X Receptor Partial Agonistic Action of 1-(3,5,5,8,8-Pentamethyl-5,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-2-Naphthyl)-1 H -Benzotriazole-5-Carboxylic Acid and Structural Development To Increase Potency. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56 (5), 1865–1877. 10.1021/jm400033f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uray I. P.; Dmitrovsky E.; Brown P. H. Retinoids and Rexinoids in Cancer Prevention: From Laboratory to Clinic. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43 (1), 49–64. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altucci L.; Leibowitz M.; Ogilvie K.; de Lera A.; Gronemeyer H. RAR and RXR Modulation in Cancer and Metabolic Disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2007, 6 (10), 793–810. 10.1038/nrd2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalloyer F.; Fiévet C.; Lestavel S.; Torpier G.; van der Veen J.; Touche V.; Bultel S.; Yous S.; Kuipers F.; Paumelle R.; et al. The RXR Agonist Bexarotene Improves Cholesterol Homeostasis and Inhibits Atherosclerosis Progression in a Mouse Model of Mixed Dyslipidemia. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26 (12), 2731–2737. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000248101.93488.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic I. M.; Horn T. L.; Johnson W. D.; Cwik M. J.; Detrisac C. J.; McCormick D. L. Murine Oncogenicity and Pharmacokinetics Studies of 9- Cis -UAB30, an RXR Agonist, for Breast Cancer Chemoprevention. Int. J. Toxicol. 2010, 29 (2), 157–164. 10.1177/1091581809360070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. I.; Gopal J.; Haugen B. R.; Chiu A. C.; Whaley K.; Nowlakha P.; Duvic M. Central Hypothyroidism Associated with Retinoid X Receptor–Selective Ligands. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340 (14), 1075–1079. 10.1056/NEJM199904083401404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuta H.; Yakushiji N.; Shinozaki R.; Ohsawa F.; Yamada S.; Ohta Y.; Kawata K.; Nakayama M.; Hagaya M.; Fujiwara C.; et al. RXR Partial Agonist CBt-PMN Exerts Therapeutic Effects on Type 2 Diabetes without the Side Effects of RXR Full Agonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3 (5), 427–432. 10.1021/ml300055n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.