Abstract

Sexting, sending, or receiving sexually suggestive or explicit messages/photos/videos, have not been studied extensively. The aims of this study is to understand factors associated with sexting among minority (e.g., African-American, Hispanic) emerging adult males and the association between sexting and sexual risk. We recruited 119 emerging adult heterosexual males and assessed sexting and sexual risk behaviors. Fifty-four percent of participants sent a sext, and 70% received a sext. Participants were more likely to sext with casual partners than with steady partners. Multiple regression analyses showed that participants who sent sexts to steady partners had significantly more unprotected vaginal intercourse and oral sex. Participants who sent sexts to casual partners had significantly more partners, and participants who received sexts from casual partners had significantly more unprotected oral sex and sex while on substances. We found that sexting is a frequent and reciprocal behavior among emerging adults, and there were different patterns of significance for sexts with casual and steady partners.

Cell phone use is widespread within the United States with over 90% of American adults owning a cell phone and 58% owning a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2014). Over 81% of Americans use their cellphones mainly to receive and send text messages (Pew Research Center, 2014). This is especially true of young adults and adolescents, with these groups using text messaging more frequently than voice calls to communicate with members of their social network (Drouin, Vogel, Surbey, & Stills, 2012). It is no surprise that mobile technology has become a major form of communication within relationships, especially to remit messages around sex, known as sexting.

Research in sexting is new and definitions vary considerably within the literature. Some definitions of sexting limit the devices that sexts are sent from to only mobile phones, while others include alternate forms of electronic communication such as computers (Henderson & Morgan, 2011; Lounsbury, Mitchell, & Finkerhor, 2011). Some definitions view sexting solely as the sending of explicit photos whereas others include messages or videos, or all three (Lounsbury et al., 2011). Lack of consensus on a definition and measurement makes comparison between studies difficult (Drouin et al., 2012; Klettke, Hallford, & Mellor, 2014; Lounsbury et al., 2011). For the purpose of this paper, we are taking a broad definition of texting by defining it as sending or receiving sexually suggestive or explicit messages/photos/videos using any form of social technology (e.g., phone text, Tinder, Twitter, instant messages, computer).

The prevalence of sexting among young adults varies greatly from study to study. In a systematic review conducted by Klettke et al. (2014) the mean prevalence of sending a sexually suggestive or explicit text/picture (e.g., What color panties are you wearing?; sending a photo in lingerie or a picture of a person’s genitalia) across 12 studies of young adult populations was 53%, whereas the mean prevalence of adolescents sending a sexually suggestive text or photo was 10%. The 2014 Love, Relationship, & Technology survey by McAfee found that 50% of adults had sent or received intimate or sexual messages from someone and 16% had sent intimate content to a stranger (McAfee, 2014). These studies suggest that there is a high prevalence of sexting within emerging adults (ages 18–25) and as a result more research is necessary to see the impact of sexting on sexual health.

A majority of the research on sexting to date has concentrated heavily on adolescents (ages 14–18) and the legal ramifications of sexting (Ahern & Mechling, 2013; Judge, 2012; Korenis & Billick, 2014; Richards & Calvert, 2009). There has been limited research focused on emerging adults and sexting, especially as it relates to sexual risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex, multiple partners) and outcomes (e.g., STIs and HIV). The few studies that have looked at emerging adults, concentrated on undergraduate college populations, who are usually more educated and of higher socioeconomic status than general populations. Therefore, these studies did not explore the prevalence of sexting and its impact on populations with higher rates of sexual risk (e.g., STIs and HIV), such as low-income and minority populations (Benotsch, Snipes, Martin, & Bull, 2013; Dir, Cyders, & Coskunpinar, 2013; Drouin et al., 2012; Englander, 2012; Ferguson, 2011; Gordon-Messer et al., 2013; Henderson & Morgan, 2011; Hudson, 2011). There is a distinct gap in looking at emerging adult populations outside of undergraduates, especially those of different race/ethnicities, where sexual risk is high and health disparities are particularly striking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). In 2010, according to the Center for Disease Control, the Chlamydia rate among Black men between the ages of 20–24 was eight times the rate among White men of the same age group (CDC, 2010). Similar, health disparities exist for unwanted pregnancy and HIV, with Black men having significantly higher rates than their White counterparts (CDC, 2010). Therefore, there is a need for more research that explores possible behaviors that may contribute to these large public health disparities.

There have been a few studies looking specifically at sexual risk and sexting but the evidence has been inconclusive (Benotsch et al., 2013; Ferguson, 2011; Gordon-Messer et al., 2013; Knowledge Networks, 2009). Some have demonstrated a strong relationship between sexting and sexual risk (Benotsch et al., 2013; Dake, Prince, & Mazlarz, 2012; Ferguson, 2011; Rice et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2012) while others have found no significant association between the two (Gordon-Messer et al., 2013). One possible reason for the mixed results is that studies often do not differentiate the direction of the sexting (i.e., who is sending and receiving the sexts) and the type of partner one is sexting with (e.g., steady vs. casual partner). The type of partner may be particularly relevant because it could differentiate between healthy sexual expression within a steady partnership versus a strategy to engage new and casual partnerships that may increase HIV risk (Gordon-Messer et al., 2013; Levine, 2013). A better understanding of how sexting direction and partner type (e.g., steady vs. casual) is linked to sexual risk behavior can inform sexual health interventions targeted within these populations.

Within the literature that exists about sexting, a number of potential predictors of this behavior have emerged. Psychosexual variables that have been linked to increased sexuality, such as sensation seeking and sexual attitudes have been linked to sexting (Benotsch et al., 2013; Crimmins & Seigfried-Spellar, 2014; Dir et al., 2013). Further, certain types of sexual behavioral expressions such as viewing pornography and frequenting strip clubs may cluster with sexting behavior (Crimmins & Seigfried-Spellar, 2014; Spenhoff, Kruger, Hartmann, & Kobs, 2013). Masculinity norms have been linked to the way individuals communicate with each other about sex and relationships using social technologies (Ogletree, Fancher, & Gill, 2014). Low self-esteem has been associated with sexual risk and problematic cell phone use (e.g., excessive and obsessive texting) which may make individuals with low self-esteem particularly likely to engage in sexting (Bianchi & Philips, 2005; Peterson, Buser, & Westburg, 2010). Finally, religiosity has been associated with self-control and self-regulation regarding engaging in sexual behaviors, and therefore may reduce the likelihood of an individual engaging in sexting (McCullough & Willoughby, 2009).

STUDY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

The overall aims of this study are to understand factors (e.g., sensation-seeking, masculinity, sexual attitudes) associated with sexting within low-income, minority, emerging adult males, and assess if there is any association between sexting behaviors and increased sexual risk (e.g., unprotected sex, number of partners, substance use during sex). We created four categories of sexting based on whether the sext was sent or received and to whom: (1) sext sent to steady partner, (2) sext received from steady partner, (3) sext sent to nonsteady partners (i.e., hookups), and (4) sext received from hookups. Much of the research has looked at sexting in terms of sending and receiving but not categorized by both sent/received and to whom (hookup/steady partner; Benotsch et al., 2013; Ferguson, 2011; Gordon-Messer et al., 2013; Houck et al., 2014).

METHODS

PROCEDURES

Secondary data analyses were conducted using a study of 119 emerging adult men from New Haven, CT, a small city in the Northeast United States with high levels of disadvantage (e.g., high poverty, crime). Participants were recruited for a larger study of social networks, cell phones, and health behavior. The recruitment process used a combination of time-location sampling and snowball sampling. First, we conducted epidemiologic assessments using census and department of public health data to identify neighborhoods within our target city with high risk (e.g., high STI rates, poverty). Next, research assistants conducted ethnographic mapping of the areas to detail specific locations and times within the neighborhoods that emerging adult men hung out (e.g., basketball courts, corners, bars, community centers). Trained research assistants approached men in these locations and told them about the study. Once a participant agreed, snowball sampling was then used to recruit friends of participants. Inclusion criteria for all participants included: (a) male gender, (b) age 18–25, (c) English-speaking, (d) heterosexual, and (e) in possession of a cell phone with texting capabilities, and ability to maintain cell phone service.

Data from these analyses are cross-sectional. During the appointment, research staff obtained written informed consent. Participants completed study measures via audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) with trained research staff. Participation was voluntary and confidential, and all procedures were approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee. Participants were remunerated $35 for their assessment.

MEASURES

Sexting

Participants answered a set of 12 questions on lifetime sexting behaviors (as defined within this study as ever sending or receiving of sexually explicit/suggestive messages, pictures, or videos). We followed a systematic process to develop the sexting questions. First, a comprehensive literature review on sexting including existing measures was conducted and summarized. Second, the research team, which consisted of experts in sexual risk, social technology, and men’s health, brainstormed and compiled possible questions based on existing literature and our conceptual definition of sexting. Finally, we received feedback from two members of the study population (i.e., Black males) on the questions including issues of face validity, wording, and whether additional questions were needed. Example questions were “Has anyone ever sent you naked or nearly naked photos or videos of themselves?” and “Have you ever sent a sexually suggestive text or instant message, for example, sexting?” Participants responded yes/no to each question. If participants responded yes, they were then asked who they sent/received the message to (e.g., steady partner, casual partner, cheating partner, stranger, acquaintance) by checking all that applied. Next, we created four sexting variables based on if sexts were ever sent or received to a steady partner or a hookup (e.g., casual partner, cheating partner, stranger, and acquaintance). The Hookup partners were grouped together because they indicate a relationship that is not steady and committed. The resulting four variables used to look at sexting were: (1) sexts sent to steady partners, (2) sexts received from steady partners, (3) sexts sent to hookups, and (4) sexts received from hookups.

Sexual Risk

Sexual risk variables were taken from questions that have been validated in previous studies using minority emerging adult men (Kershaw, Arnold, Lewis, Magriples, & Ickovics, 2011).

Number of Casual Partners in the Past 3 Months.

Participants were asked how many sexual partners they had in the past 3 months, and of those how many were casual partners.

Unprotected Vaginal Sex Occasions in the Past 30 Days.

Participants were asked the number of times they had sex in the past 30 days, and of those times, the number of times they had used condoms. This variable was obtained by subtracting the number of times they used condoms from the number of times they had sex. If the participants reported not having sex, they received a 0.

Unprotected Oral Sex Occasions in the Past 30 Days.

This variable was obtained by subtracting the number of times participants used condoms while receiving oral sex from the number of times they received oral sex in the past 30 days. If the participants reported not having oral sex, they received a 0.

Number of Times Participant Used Drugs/Alcohol During Sex in the Past 30 Days.

This variable was obtained by asking participants of the times they had sex, how many times were they on alcohol or drugs. If the participants reported not having sex, they received a 0.

Number of Times Partners Used Drugs/Alcohol During Sex in the Past 30 Days.

This variable was obtained by asking participants of the times they had sex, how many times their partner was on alcohol or drugs. If the participants reported not having sex, they received a 0.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants reported their age, income, race/ethnicity, education, how religious they were and whether they were in a romantic relationship at the time or not by asking “Are you currently in a romantic relationship (a relationship that you consider your partner to be your main partner, girlfriend, or your girl)?”

PREDICTORS

Risky and Reckless Behavior.

This was assessed through nine items (Arnett, 1996) intended to measure how often participants engaged in risky and reckless behaviors (e.g., In the past 6 months, how many times have you driven an automobile while intoxicated? In the past 6 months, how many times have you shoplifted?) Participants scored their answers on a scale from 0 (0 times) to 5 (more than 20 times). We calculated a mean risk and reckless behavior score with a higher score indicating riskier behavior. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81, showing good reliability.

Positive Sexual Sensation-Seeking.

This modified scale consisted of four questions to assess if the participants considered themselves someone who engaged in sexually adventurous behavior (Kalichman et al., 1994). Questions included: “I like wild uninhibited sexual encounters” and “I feel like exploring my sexuality.” The answers to these questions were rated on a four point scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). The scale has been previously validated for inner city men (Kalichman et al., 1994). The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.67, showing fairly good reliability.

Sexual Attitudes.

This was measured through ten questions from the Hendrick Sexual Attitude Scale (HSAS; Hendrick & Hendrick, 1987). Example questions included: “It is okay to have ongoing sexual relationships with more than one person at a time,” “It is possible to enjoy sex with a person and not like that person very much.” Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These items intended to evaluate the participants’ overall openness to sex including permissiveness and various sexual practices. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, showing good reliability.

Sensation Seeking.

This was assessed through an 11-item scale looking at sensation-seeking behaviors (Kalichman et al., 1994). Each item was a statement (e.g., I would like parachute jumping, I have been known by my friends as a risk taker) and was scored by participants on a 4-point scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). We created a mean sensation-seeking score with higher scores indicating higher sensation seeking. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83, showing good reliability.

Communicate With Friends About HIV/AIDS.

Participants were given a statement “with my closest friends I talk about HIV/STDs” and answered using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

Communicate With Friends About Sex.

Participants were given a statement “with my closest friends I talk about sex” and answered using a five point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

Masculinity Norms.

We assessed masculinity norms from the Masculine Norm Scale (MRNS) developed by Thompson and Pleck (1986). This scale had three subscales: masculinity status norms, masculinity toughness, and masculinity anti-femininity. Masculine status norms had 11 items (e.g., Success in his work has to be a man’s central goal in this life). Masculinity toughness was assessed with 8 items (e.g., When a man is feeling a little pain he should try not to let it show much). Masculine anti-femininity was assessed with 5 items (e.g., It is a bit embarrassing for a man to have a job that is usually filled by a woman). The participants are asked to respond using a 7-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We calculated mean scores for each subscale and higher scores indicated more status norms, toughness, and anti-femininity. Results showed good internal consistency for status (α = .86), toughness (α = .71), and anti-femininity (α = .67).

Exposure to Pornography and Strip Clubs. This was assessed through two questions, which asked if the participants had watched pornography and gone to a strip club in the last three months. Responses were yes/no.

Religion.

Participants were asked how religious they were. This was measured on a scale from 0 (not at all religious) to 3 (very much so).

Self-Esteem.

Self-esteem was assessed using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants responded to items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81, showing good reliability.

DATA ANALYSIS

Frequencies were assessed to describe sexting behaviors among emerging adult men.

Next, unadjusted associations were assessed between predictor variables and each of our four sexting variables: (1) sext sent to steady partner, (2) sext received from steady partner, (3) sext sent to hookup, and (4) sext received from hookup. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess factors associated with sexting. We ran backward logistic regressions to identify the best predictive model for each sexting variable. Next, to analyze sexual risk and sexting, unadjusted and adjusted multiple regression analysis models were conducted using backward selection to identify the best predictive model for all of the sexual outcomes. All analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago).

RESULTS

The sample consisted of heterosexual males with a racial breakdown of 79.0% Black, 16.8% Latino, and 4.2% White. The average age of the participants was 20 years (SD = 1.97), the average household income was $20,965 (SD = 24,484), and the average level of education reached was Grade 12 (SD = 1.68). Over half of the participants were in a romantic relationship (54.6%) and somewhat religious (68%).

SEXTING BEHAVIORS AND PREVALENCE

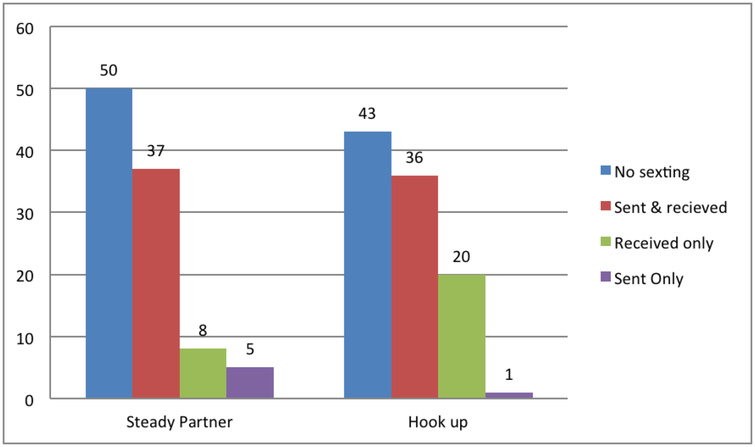

Results showed that participants were more likely to have received a sext than sent a sext (70% vs. 54%, p < .001). Fifty-one percent of participants had both sent and received a sext; 19% had received but never sent a sext; 3% had sent but never received a sext; and 27% had neither sent nor received a sext. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the four sexting groups by who the sexts were sent to and received from. Participants were more likely to sext hookups than steady partners (p < .01). Further, the largest difference was that participants were more likely to be in the receive-only group for hookups compared to steady partners (20% vs. 8%, p < .01). However, there were no differences in the likelihood of sending sexts to steady partners versus hookups (p = .345). Participants were more likely to receive sexts from hookups than to send sexts to hookups (56 vs. 37%, p < .001). However, there were no differences in receiving and sending sexts to steady partners (p = .607).

FIGURE 1.

Sexting by Type of Partner

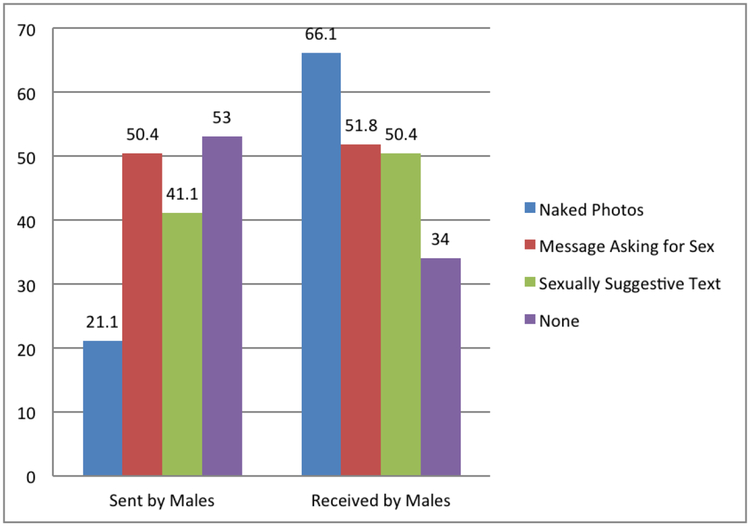

Figure 2 shows the different types of sexting behaviors for sexts sent and received. All types of sexting behaviors (sending/receiving naked photos, asking for sex, and sexually suggestive texts) were more commonly received than sent by men. The most common type of sext received by men were naked photos. The most common type of sexting behavior sent by men was sending messages asking for sex.

FIGURE 2.

Sexting Behaviors Sent and Received

PREDICTORS OF SEXTING

Unadjusted results predicting sexting are shown in Table 1. Results show that older, wealthier, more educated individuals, individuals who engaged in more risky and reckless behavior, had more positive sexual sensation-seeking behaviors, talked more frequently with friends about relationships, and watched porn in the last three months were more likely to have received a sext from a steady partner. Individuals who engaged in more positive sexual sensation-seeking behaviors, talked more frequently with friends about relationships, had more open and permissive attitudes towards sex, and watched porn in the last three months were more likely to send a sext to a steady partner. For sexts received from a hookup, having engaged in more risky and reckless behavior, more positive sexual sensation-seeking behavior, having more open and permissive attitudes toward sex, talking more frequently with friends about relationships and sex, and exposure to porn and strip clubs were related to having received a sext from a hookup. For sexts sent to a hookup, more education, more risky and reckless behavior, more positive sexual sensation seeking, talking more frequently with friends about sex, and exposure to porn were related to having sent a sext to a hookup

TABLE 1.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Models Predicting Sexting

| Variable | Sexts received from steady partner | Sext sent to steady partner | Sexts received from hookup | Sexts sent to hookup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Models | ||||

| Race (Black) | 1.05 (0.42,2.63) | 0.6 (0.24, 1.51) | 0.61 (0.24, 1.57) | 0.56 (0.22, 1.42) |

| Age | 1.27(1.04, 1.54)* | 1.02 (0.85, 1.23) | 1.01 (0.84, 1.22) | 1.17(0.96, 1.43) |

| Income | 1.23 (1.02, 1.48)* | 1.18 (0.99, 1.41) | 1.10 (0.92, 1.31) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.45) |

| Education | 1.25 (0.99, 1.57)* | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) | 1.15 (0.92, 1.44) | 1.43 (1.11, 1.83)* |

| Risky and Reckless Behavior | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19)* | 1.18 (1.08, 1.30) | 1.16 (1.05, 1.28)* | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21)* |

| Positive Sexual Sensation Seeking | 1.16 (1.01, 1.32)* | 1.23 (1.06, 1.42)* | 1.18 (1.03, 1.36)* | 1.28 (1.10, 1.49)* |

| Sexual Attitudes | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07)* | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07)* | 1.03 (0.10, 1.06) |

| Sensation Seeking | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.08) |

| Talk With Friends About HIV/AIDS | 1.14 (0.85, 1.53) | 1.11 (0.82, 1.48) | 1.09 (0.81, 1.46) | 1.11 (0.82, 1.49) |

| Talk With Friends About Relationships | 1.95 (1.32, 2.87)* | 1.70 (1.17,2.45)* | 1.54(1.089,2.17)* | 1.58 (1.09,2.28) |

| Talk With Friends About Sex | 2.34(1.57, 3.47) | 2.34 (1.56, 3.50) | 1.54(1.12,2.13)* | 1.86 (1.28,2.69)* |

| Masculinity Status Norms | 0.87(0.61, 1.23) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.33) | 1.150 (0.811, 1.630) | 1.16 (0.80, 1.67) |

| Toughness | 1.10 (0.77, 1.56) | 1.288 (0.898, 1.848) | 1.169 (0.821, 1.665) | 1.17 (0.82, 1.68) |

| Anti-femininity | 0.81 (0.57, 1.15) | 0.07(0.76, 1.53) | 0.99 (0.70, 1.41) | 1.025 (0.71, 1.47) |

| Exposure to Porn | 4.93 (2.16, 11.24)* | 7.03 (2.96, 16.72)* | 2.40 (1.08, 5.32)* | 6.88 (2.84, 16.69)* |

| Exposure to Strip Clubs | 0.71 (0.23,2.17) | 0.57(0.18, 1.81) | 0.28 (0.09, 9.0)* | 1,00 (0.33, 3.05) |

| Religious | 1.24 (0.83, 1.85) | 0.98 (0.66, 1.46) | 0.77(0.52, 1.16) | 1.22 (0.81, 1.84) |

| Self-Esteem | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.15) |

| Adjusted Final Models | ||||

| Education | — | — | — | 1.63 (1.16,2.30)* |

| Risky and Reckless Behavior | — | — | 1.15 (1.02, 1.29)* | — |

| Sexual Attitudes | — | — | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08)* | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10)* |

| Talk With Friends About Sex | 1.95 (1.21,3.13)* | 2.22 (1.35,3.68)* | — | — |

| Exposure to Porn | 5.29 (1.99, 14.09)* | 5.42 (1.98, 14.82)* | — | 6.31 (2.27, 17.55)* |

Notes. Values represent odds ratios.

p< .05.

The results from the adjusted model (see Table 1) show that predictors for sending or receiving a sext from a steady partner were: exposure to porn (OR = 5.29, p < .01) and talking more frequently with friends about sex (OR = 1.96, p < .05). Those who watched porn in the past three months were 5.29 times more likely to have received a sext from a steady partner and 5.42 times more likely to have sent a sext to steady partner (OR = 5.42, p < .01). Young men who engaged in more risky and reckless behaviors (OR = 1.15, p < .05) and had more open attitudes about sex (OR = 1.04, p = .05), were more likely to have received a sext from a hookup. Those who had higher education (OR = 1.63, p < .05), more open attitudes about sex (OR = 1.05, p < .05) and who watched porn in the last three months (OR = 6.31, p < .05) were more likely to have sent a sext to a hookup.

SEXTING AND SEXUAL RISK

Unadjusted associations showed that having sent sexts to hookups related to more casual partners in the past 3 months (β = .185, p < .05; see Table 2). Having sent sexts to (β = .274, p < .01) and received sexts from (β = .221, p < .05) steady partners related to more unprotected vaginal sex occasions in the past 30 days. Having sent sexts to steady partners (β = .364, p < .01) and hookups (β = .189, p < .05), and having received sexts from steady partners (β = .361, p < .01) and hookups (β = .306, p < .01) related to more unprotected oral sex occasions. Sending sexts to steady partners (β = .204, p < .05) and receiving sexts from hookups (β = .247, p < .05) related to more use of drugs/alcohol during sex for participants and partners.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Models of Sexting and Sexual Risk

| Variable | # Casual Partners | Unprotected Vaginal Sex Occasions | Unprotected Oral Sex Occasions | # Times Used Drugs/Alcohol During Sex | # Times Partner Used Drugs/Alcohol During Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Models | |||||

| Black Race | .020 | −.116 | −.044 | −.066 | −.078 |

| Age | .081 | .091 | .101 | .204* | .098 |

| Income | .041 | .071 | .119 | .027 | .087 |

| Education | .014 | .020 | .189* | .187 | .062 |

| Sexts Sent to Steady Partner | −.010 | .274** | .364** | .208* | .204* |

| Sexts Received From Steady Partner | .006 | .221* | .361** | .175 | .164 |

| Sexts Sent to Hookup | .185* | .139 | .189* | . 133 | .109 |

| Sexts Received From Hookup | .044 | .098 | .306** | .249* | .247* |

| Adjusted Final Models | |||||

| Age | .221* | ||||

| Sexts Sent to Steady Partner | .274** | .289** | |||

| Sexts Received From Steady Partner | |||||

| Sexts Sent to Hookup | .185* | ||||

| Sexts Received From Hookup | .188* | .252** | .247* |

Notes. Values represent Beta weights.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The adjusted models show that individuals with a history of sending sexts to steady partners had more unprotected vaginal intercourse (β = .274, p < .01) and oral sex occasions in the past 30 days (β = .289, p < .01; see Table 2). Further, individuals with a history of sending sexts to hookups had more casual partners in the past 3 months (β = .185, p < .05). Finally, individuals with a history of receiving sexts from hookups had more unprotected oral sex occasions in the past 30 days (β = .188, p < .05) and more times that they had sex while they (β = .252, p < .01) or their partner (β = .247, p < .05) were on drugs or alcohol.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that sexting was very common among a sample of low-income mostly minority emerging adult males. The vast majority of participants reported sexting, with only 27% having never engaged in the behavior. Overall the findings demonstrate that sexting is a reciprocal behavior with those who sext most likely engaging in both sending and receiving sexts. However, men seemed to be more passive than their female partners, with men much more likely to receive than send sexts. This confirms research by Gordon-Messer et al. (2013) that men were more likely to be receivers of text messages than females. In particular, we found men rarely sent sexts without receiving them. However, men frequently received sexts without sending them, particularly from hookups.

Further, results showed that men did not markedly differ in whether they sexted with hookups than with steady partners (57% vs. 50%), indicating that sexting may be used by men both as a way to initiate sexual encounters and to maintain sexual relationships. But the nature of the sexting seemed to differ within the two groups, with men more likely to receive sexts from hookups and to send sexts to steady partners. This is consistent with the literature, which shows that those in committed relationships are more likely to send sexts (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013; Dir et al., 2013; Drouin et al., 2012; Hudson, 2011). This demonstrates a clear difference in how sexts work within the two categories of relationships and shows a different engagement with the behavior on the part of young men. This could imply that there are gender norms at play within sexting behaviors and that technology could be mediating and shifting the norms about sexual initiation and interactions between males and females. Perhaps in the sexting world, females are more likely to initiate than males are, or the expectations differ on what is acceptable and when, from males and females. Of the few research studies looking at gender norms and texting, Olgetree and colleagues (2014), found gender role was a significant indicator in the type of text messages sent and received, as well as the volume. Those with traditional feminine norms were more likely to be the initiators of messages and send more texts, whereas people with traditional masculine norms were more likely to receive text messages and engage only when someone else initiated. This could also be linked with the outcomes young men hope to receive from steady partners versus hookups (longstanding relationship versus immediate sex) and this difference may have effects on sexual risk.

A study by Benotsch et al. (2013) found that 14% of participants reported having sex with a new partner for the first time after sexting, implying that sexting may be a technology-mediated flirtation strategy. The results from our study support this theory, but more research is needed to ascertain if this is indeed the case. It is not clear the temporal order of the sexting (e.g., who sent the first sext), whether men prompted or asked for sexts (e.g., send me a picture), or the social media platform used (e.g., Tinder, Twitter, texts) that may have resulted in the nature of the patterns that we found. Understanding how young men are sending and receiving sexts and the motivations behind their sexting behavior could direct future research when looking at sexual risk and the implications of these sexting patterns.

Our results show that a history of sexting is linked to a variety of sexual risky behaviors such as more partners, more unprotected sex, and having sex while under the influence of drugs and alcohol. More importantly, these results vary depending on to whom the messages are sent.

There has been limited research looking specifically at sexual risk and sexting within a low-income minority emerging adult population. A study of primarily Hispanic women by Ferguson (2011) found that sexting was not associated with riskier sexual behaviors (number of partners or unprotected sex with new partners) whereas a study by Benotsch et al. (2013) found that sexting was related to riskier sexual behaviors (multiple partners, unprotected sex, STIs) in a sample of undergraduate college students. The findings between sexting and sexual behavior in this study support the perspective that sexting is part of emerging adults sexual relationships and is correlated with engagement in riskier sexual behaviors that could put young men at heightened risk for STIs and HIV. The results show that both sending and receiving sexts was related to STI/HIV sexual risk behavior and that the risk differed between steady partners and hookups. Results showed that sending sexts to steady partners and receiving sexts from hookups were most related to sexual risk behavior.

The predictors of sexting give insight into sexting behavior and basic motivations. These predictors differ slightly depending on whether the sext is sent or received and to whom. However, exposure to sexual stimuli, i.e., pornography, factored in as a predictor for almost all types of sexting. It is possible that pornography desensitizes young men about sex or provides a modeling of behavior and language that is used during sexting. Future research could explore whether porn exposure influences sexting behavior and language (perhaps by doing a content analysis of sexts), and qualitative interviews about whether participants learn the language and style they use for sexting from pornography. There may be a peer component present around sexting as talking with friends about sex was an important predictor. The predictors surrounding sexts sent and received to hookups align with general risky behaviors, permissive sexual attitudes and exposure to sexual stimuli which create a greater amount of general risk within this group, especially given the hookup category includes strangers. Future studies are needed to ascertain the motivations behind sexting and how these are linked to sexual risk. Future research looking at if the behavior is an intentional means of trying to have more sex or a substitute for sex, could inform the link between sexting and sexual risk.

The implications of this study are that sending and receiving of sexts as well as who the sexts are sent to and received from are important both in looking at the predictors of sexting and at looking at the sexual risk. Future studies should ensure that these distinctions are made when looking at the effects of sexting on health and differentiating between steady partners and casual partners. Future research should aim to create uniform definitions and measurements of sexting so that studies can be compared and research can have a better impact on related health behaviors. Currently it is difficult to compare prevalence rates and other indicators across studies. Further research is also needed to see if sexting establishes norms which are related to sexual risk or if certain personality types that are prone to sexting.

In addition studies looking at sexting and positive outcomes are also needed to establish if there are good outcomes to this behavior such as feeling closer in a relationship, greater sexual satisfaction or greater intimacy within a relationship. There has been some research looking at technology and relationships where 41% of 18–29 year-old participants in a committed relationship have felt closer to their partner because of exchanges they have had online or via text, but is not specific to sexting (Lenhart & Duggan, 2014).

LIMITATIONS

This sample consisted of mainly low-income minority males and as a result may not be generalizable to other populations. However, to date there has been no research focused on sexting of low-income minority emerging adult males, and this adds to the literature base. The data mostly relied on self-report and participants may have been over-reporting or under-reporting sexting behaviors. Future studies could use text logs to provide objective assessments of sexting. Further, several questions (e.g., sexting, pornography exposure) were asked as yes/no. Using a scale to assess frequency/magnitude of exposure to pornography and strip clubs may provide a more nuanced understanding of this type of exposure and should be explored in future studies. Social desirability bias may play into this, although the conditions under which the surveys were completed (e.g., ACASI interviews) ensured each participant had privacy. In addition, the study is cross-sectional and therefore causality cannot be determined. The questions measuring sexting looked at this behavior over a lifetime, whereas some of the predictors were assessing current behaviors. Longitudinal studies are needed to better ascertain the nature of the relationship between sexting and sexual risk. The study did not look at the motivations behind sexting or the temporal nature of sexting, which may be an important piece when looking at risk. For example, participants received more sexts than they sent. It is not fully understood why this was and the possible interpersonal dynamics that may foster engagement and response in sexting. Understanding why people engage in this behavior, and what they hope to gain through it, could inform the relationship with sexual risk. Future studies could explore qualitative interviews to better understand motivations and patterns of communication or monitor texts directly.

CONCLUSIONS

More research is needed to determine causality between sexting and sexual risk. Despite not knowing the full structure of the relationship between sexting and sexual risk, knowing who are at risk has implications for behavioral interventions. Separate targeted interventions could be developed for males in long-term relationships and for those who are not in long-term relationships. Couples who engage in this form of computer mediated communication can be taught how to use sexting to increase intimacy and connection, while reinforcing the importance of safe sex (Parker, Blackburn, Perry, & Hawks, 2013). Males who are more likely to have casual hookups can be taught how to integrate sexual risk reduction and sexual safety into their sexting behaviors, and the best methods to protect themselves from STIs and HIV.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by R21DA031146 (PI = Kershaw), an HIV T32MH020031 (PI = Kershaw), and by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (5P30MH062294).

We acknowledge the contributions of Lauren Perley, Jonathan Bailey, Tashuna Albritton, and Crystal Gibson.

REFERENCES

- Ahern NR, & Mechling B (2013). Sexting: Serious problems for youth. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 51, 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (1996). Sensation seeking, aggressiveness, and adolcesent reckless behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 20, 695–702. [Google Scholar]

- Benotsch EG, Snipes DJ, Martin AM, & Bull SS (2013). Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 307–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A, & Phillips JG (2005). Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 8, 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). 2010 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance: STDs in racial and ethnic minorities. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/minorities.htm

- Crimmins DM, & Seigfried-Spellar KC (2014). Peer attachment, sexual experiences, and risky online behaviors as predictors of sexting behaviors among undergraduate students. Computers in Human Behaviour, 32, 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Dake JA, Prince JH, & Mazlarz L (2012). Prevalence and correlates of sexting behavior in adolescents. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Delevi R, & Weisskirch RS (2013). Personality factors as predictors of sexting. Computers in Human Behaviour, 29, 2589–2594. [Google Scholar]

- Dir AL, Cyders MA, & Coskunpinar A (2013). From the bar to the bed via mobile phone: A first text of the role of problematic alcohol use, sexting and impulsivity-related traits in sexual hookups. Computers in Human Behaviour, 29, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Drouin M, Vogel KN, Surbey A, & Stills JR (2012). Let’s talk about sexting, baby: Computer-mediated sexual behavior among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Englander E (2012). Low risk associated with most teenage sexting: A study of 617 18-year-olds. MARC Research Reports, Paper 6. Retrieved December, 12, 2012, from http://vc.bridgew.edu/marc_reports/6

- Ferguson CJ (2011). Sexting behaviors among young Hispanic women: Incidence and association with other high-risk sexual behaviors. Psychiatric Quarterly, 82, 239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Messer D, Bauermeister JA, Grodzinski A, & Zimmerman M (2013). Sexting among young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 301–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L, & Morgan E (2011). Sexting and sexual relationships among teens and young adults. McNair Scholars Research Journal, 7, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick S, & Hendrick C (1987). Multidemsionality of sexual attitudes. Journal of Sex Research, 23, 502–526. [Google Scholar]

- Houck CD, Barker D, Rizzo C, Hancock E, Norton A, & Brown LK (2014). Sexting and sexual behavior in at-risk adolescents. Pediatrics, 133, e276–e282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson HK (2011). Factors affecting sexting behaviors among selected undergraduate students. Retrieved March 19, 2014, from http://ehs.siu.edu/her/_common/documents/hudson-prospectus.pdf

- Judge AM (2012). “Sexting” among US adolescents: Psychological and legal perspectives. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20, 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Johnson JR, Adiar V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, & Kelly JA (1994). Sexual sensation seeking: Scale development and prediciting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62, 385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Arnold A, Lewis JB, Magriples U, & Ickovics JR (2011). The skinny on sexual risk: The effects of BMI on STI incidence and risk. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 1527–1538. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9842-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klettke B, Hallford DJ, & Mellor DJ (2014). Sexting prevalence and correlates: A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge Networks. (2009). Associated Press-MTV Poll: Digital Abuse Survey. Retrieved from http://surveys.ap.org/data/KnowledgeNetworks/AP_Digital_Abuse_Topline_092209.pdf

- Korenis P, & Billick SB (2014). Forensic implications: Adolescent sexting and cyberbullying. Psychiatric Quarterly, 85, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, & Duggan M (2014). Couples, the Internet and social media (Pew Internet and American Life Project). Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/11/main-report-30/ [Google Scholar]

- Levine D (2013). Sexting: A terrifying health risk … or the new normal for young adults? Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 257–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury K, Mitchell KJ, & Finkerhor D (2011). The true prevelence of sexting. Retrieved March 25, 2014, from http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/Sexting%20Fact%20Sheet%204_29_11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- MacAfee. (2014). Love, relationships & technology. Retrieved February 20, 2014, from http://promos.mcafee.com/offer.aspx?id=605366&culture=enus&cid=140612

- McCullough ME, & Willoughby LB (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations and implications. Psychology Bulletin, 135, 69–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogletree SM, Fancher J, & Gill S (2014). Gender and texting: Masculinity, femininity, and gender role ideology. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Parker TS, Blackburn KM, Perry MS, & Hawks JM (2013). Sexting as an intervention: Relationship satisfaction and motivation considerations. American Journal of Family Therapy, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CH, Buser TJ, & Westburg NG (2010). Effects of familial attachment, social support, involvement and self-esteem on youth substance use and sexual risk taking, Family Journal, 18, 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2014). Mobile technology fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/

- Rice E, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, Sanchez M, Montoya J, Plant A, & Kordic T (2012). Sexually explicit cell phone messaging associated with sexual risk among adolescents, Pediatrics, 130, 667–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RD, & Calvert C (2009). When sex and cell phones collide: Inside the prosecution of a teen sexting case. Retrieved March 23, 2014, from http://comm.psu.edu/assets/pdf/pennsylvania-center-for-the-first-amendment/sexcellphones.pdf

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spenhoff M, Kruger TH, Hartmann U, & Kobs J (2013). Hypersexual behavior in an online sample of males: Associations with personal distress and functional impairment. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 2996–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Paul JA, van den Berg P, Le VD, McElhany A, & Temple BW (2012). Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 166, 828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, & Pleck JH (1986). The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 531–543. [Google Scholar]