Abstract

We have recently developed a biochemical approach to isolate miRNA-bound mRNAs and have used this method to identify the genome-wide mRNAs regulated by the tumor suppressor miRNA miR-34a. This method involves transfection of cells with biotinylated miRNA mimics, streptavidin pulldown, RNA isolation, and qRT-PCR. The protocol in this chapter describes these steps and the issues that should be considered while designing such pulldown experiments.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Pre-miRNA, MicroRNP, RISC, Native agarose gel, Native PAGE, Argonaute, Dicer, Ribonucleoprotein, RNA-protein

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are an abundant class of small (~22 nucleotides) regulatory RNAs that play crucial roles in diverse cellular processes [1, 2]. Each miRNA can regulate the expression of hundreds of genes by binding to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs to inhibit mRNA translation and/or reduce mRNA stability [3–5]. MiRNA-mediated gene silencing is executed by the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) consisting of several proteins including the Argonaute (AGO) proteins which bind to miRNAs and mediate target mRNA recognition. Identifying the targets of a miRNA is essential to understand its biological function. However, identifying miRNA targets is not straightforward mainly due to partial complementarity between a miRNA and its target mRNA [6, 7]. Base-pairing between a miRNA and its target mRNA involves a small stretch of six to eight nucleotides (seed region) at the 5′-end of the miRNA, and as a result, in silico tools predict thousands of miRNA-regulated genes. Moreover, some miRNA targets can also be regulated through the coding region or 5′ UTR [8, 9]. We and others have recently shown that some targets of miRNAs are regulated through noncanonical binding sites [10–13]. The rules of miRNA-mediated gene silencing are therefore complex and emphasize the need to develop experimental approaches to identify direct miRNA targets.

Although bioinformatic algorithms are useful in identifying miRNA targets, even the best algorithms such as TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org) have a high false-positive rate, typically predicting thousands of target genes for each miRNA. Moreover, the overlap of predicted targets between different algorithms is relatively small and these in silico predictions are not cell type or context-specific. Combining bioinformatics with genome-wide approaches such as microarrays or proteomics upon miRNA overexpression or knockdown have been helpful in identifying miRNA targets [5, 12, 14–16]. Recently, biochemical approaches such as immunoprecipitation (IP) of Argonaute proteins have been used to identify direct miRNA targets by performing microarray analyses from Argonaute IPs [17, 18]. More recently, high-throughput sequencing coupled with UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) was employed to identify the sequences in endogenous RNAs that are targeted by miRNAs in living cells [19]. An improved CLIP approach, called photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP) has also been recently developed, in which a photo-activatable ribonucleoside analog (such as 4-thiouri-dine) is incorporated into transcripts of cultured cells and miRNA target sites can be identified by scoring for thymidine to cytidine transitions in the sequenced cDNA [20]. These biochemical approaches have provided genome-wide data sets of endogenous miRNA targets, miRNA-targeting rules, and biological roles of miRNAs. These technologies are continuing to evolve and are being applied to unique questions of miRNA biology.

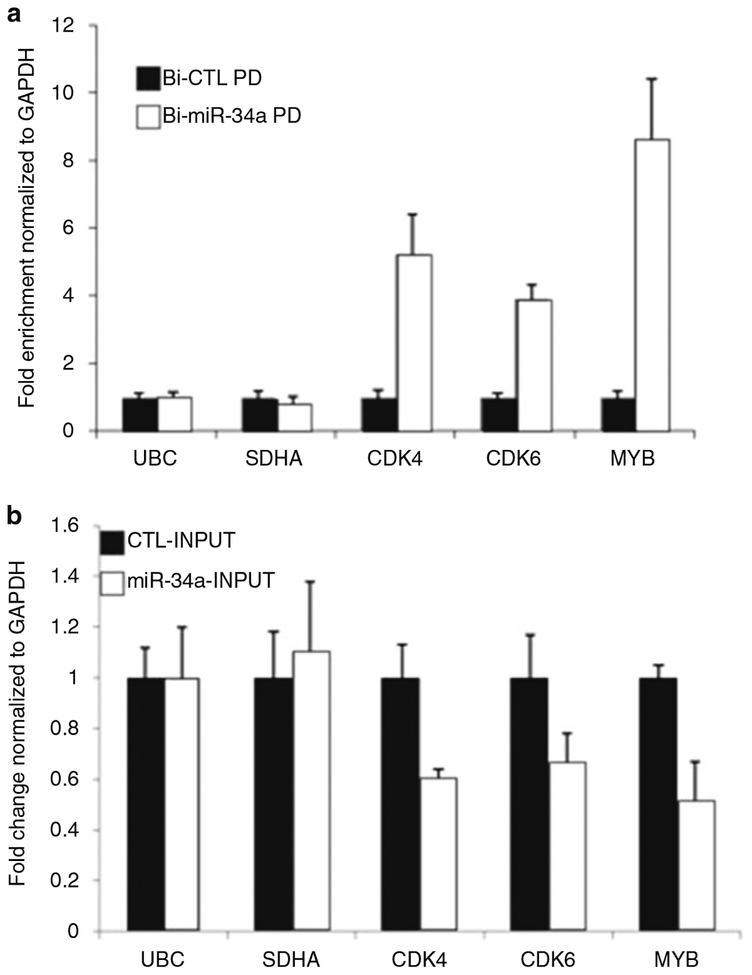

Recently, we developed a biochemical approach to isolate miRNA-bound mRNAs and used it to identify the genome-wide mRNAs regulated by the tumor suppressor miRNA miR-34a [21]. To do this, modified miR-34a mimics (RNA duplexes consisting of miR-34a and the passenger strand), in which a biotin molecule was covalently attached to the 3′ end of the mature miR-34a strand (also called antisense strand) were introduced into HeLa (human cervical cancer cells by transient transfection and BiotinmiR-34a-mRNA complexes were isolated from cytoplasmic extracts using streptavidin beads) (Fig. 1). To develop the pulldown (PD) method, we measured the abundance of known miR-34a target mRNAs (CDK4, CDK6, and MYB) in the Biotin-miR-34a (Bi-miR-34a) pulldowns by qRT-PCR. The abundance of these mRNAs was also determined in control pull-downs performed from HeLa cells transfected with the control (Bi-CTL) biotinylated C. elegans miRNA (cel-miR-67) mimics. As shown in Fig. 2a, miR-34a target mRNAs CDK4, CDK6 and MYB were significantly enriched in the Bi-miR-34a PD but not in the control PD. Transcripts encoding housekeeping mRNAs UBC and SDHA were not enriched in the PDs demonstrating the specificity of the PD assay. Introduction of Bi-miR-34a in HeLa cells also resulted in down-regulation of CDK4, CDK6 and MYB mRNAs (Fig. 2b) as measured by qRT-PCR from the input samples. The PD method was therefore able to isolate miR-34a-target mRNAs, even though these mRNAs were destabilized by Bi-miR-34a. Recently, we performed microarrays from PD samples to identify the genome-wide targets of miR-34a, miR-21, and miR-519 [21–23]. This strategy enabled us to identify key targets and pathways regulated by these miRNAs. For example, the PDs enabled us to identify a novel role of miR-34a in regulation of growth factor signaling [21]. We believe that the PD method is a straightforward strategy and can be used to discover miRNA targets (a) to provide mechanistic insights about how a miRNA regulates a specific phenotype, and/or (b) to identify phenotypes that a miRNA may regulate.

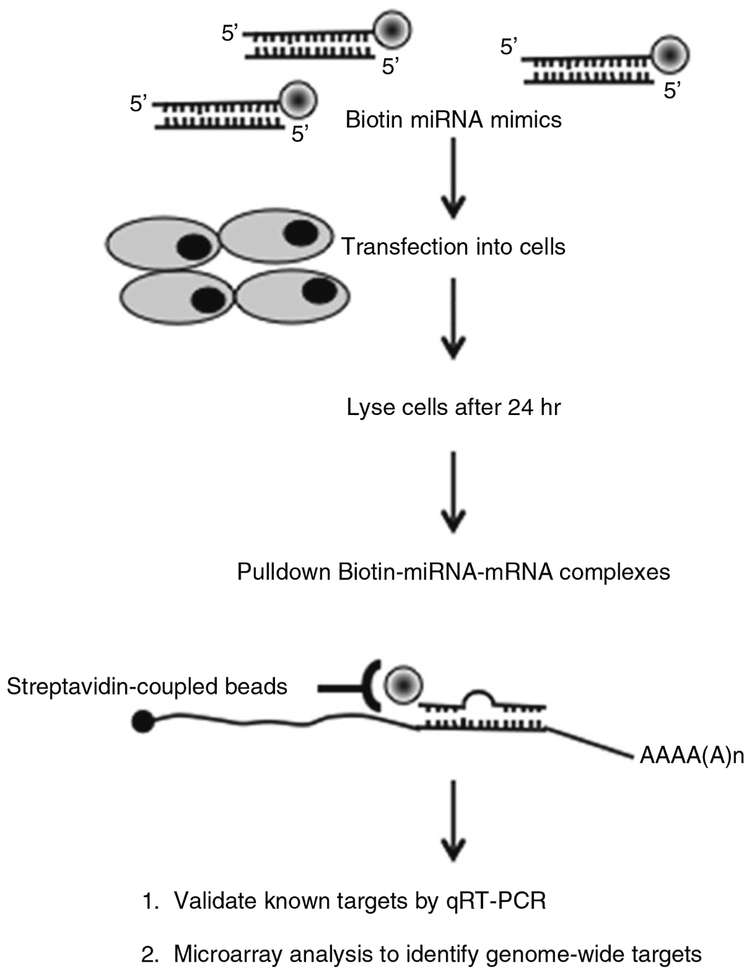

Fig. 1.

Overview of pulldown method. 3′-Biotinylated miRNA mimics are transfected into cells and cytoplasmic extracts are prepared after 24 h. The Biotin-miRNA-mRNA complexes are isolated from cytoplasmic extracts using streptavidin beads. RNA isolated from the pulldown material is used to determine the enrichment of known targets of the miRNA. Microarray analysis from the pulldown RNA can be used to identify the genome-wide mRNAs bound by the transfected Biotin-miRNA

Fig. 2.

The pulldown method captures miR-34a target mRNAs that are actively degraded. (a) HeLa cells were transfected with Bi-CTL or Bi-miR-34a for 24 h. Enrichment of 3 miR-34a target mRNAs (CDK4, CDK6, and MYB) in streptavidin pulldowns was assessed by qRT-PCR of PD RNA normalized to gApdH. (b) Effect of Bi-miR-34a on the levels of the miR-34a target mRNAs CDK4, CDK6 and MYB was determined by qRT-PCR from input RNA normalized to GAPDH. Housekeeping mRNAs UBC and SDHA were used as negative controls

The PD method can be divided into the following steps: (1) transfection of cells with biotinylated miRNA mimics, (2) beads preparation, (3) lysate preparation, (4) streptavidin pulldown, (5) RNA isolation, and (6) qRT-PCR. The protocol in this chapter describes these steps and the issues that should be considered while designing the pulldown experiment.

2. Materials

2.1. Cell Culture

HeLa (Human cervical cancer) cells.

2.2. Transfection Reagents

Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, cat# 11668–030), Opti-MEM (Invitrogen cat# 31985–062), and 3′-Biotin-miRNA mimics (Dharmacon/Thermo Scientific). Note that the 3′-Biotin-miRNA mimics are custom-made and contain a single biotin molecule covalently attached to the 3′-end of the mature strand (also called antisense strand).

2.3. 1× Binding and Washing Buffer (Store at Room Temperature)

Prepare 50 ml 1× Binding and Washing buffer by adding 250 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, and 10 ml of 5 M NaCl to 39.7 ml nuclease-free H2O. Prepare all reagents in nuclease-free H2O (Ambion cat# AM9932).

2.4. Solution A and Solution B (Store at RT)

Solution A: To prepare 50 ml solution A dissolve 200 mg NaOH in 20 ml nuclease-free H2O (final concentration 0.1 M), add 500 μl of 5 M NaCl solution (final concentration 0.05 M) and adjust the volume to 50 ml with nuclease-free H2O.

Solution B: Prepare 50 ml solution B by adding 1 ml 5 M NaCl to 49 ml nuclease-free H2O.

2.5. Lysis Buffer (Store at 4 °C)

Prepare 50 ml lysis buffer by adding 1 ml 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5),2.5 ml 2 M KCl, 250 μl 1 M MgCl2, 150 μl NP-40 and 46.1 ml nuclease-free H2O. Before the pulldowns, prepare 1.5 ml lysis buffer containing 7.5 μl RNaseOUT (Invitrogen, cat# 10777–019) and 60 μl 25× EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, cat# 11873580001).

2.6. Pulldown Reagents

Streptavidin-Dynabeads M-280 (Invitrogen, Cat# 65001), BSA (Ambion, Cat# AM2616), yeast tRNA (Ambion, Cat# AM7119) and Magnetic Separation Stand (Promega, Catalog # Z5332).

2.7. RNA Isolation

Acid-phenol:chloroform (Ambion, AM9720), Glycoblue (Ambion, cat# AM9516), Ethanol, 10 % SDS (Ambion, AM9822), sodium acetate pH 5.2 (Quality Biological, Inc. cat# 351-035-721), and Proteinase K (Invitrogen, 25530015).

2.8. Reverse Transcription and Real-Time PCR

iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BIO-RAD, cat # 170–8896) for reverse transfection. SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems cat# 4309155) and SteponePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) for real-time PCR.

3. Methods

3.1. Transfection

Seed HeLa cells in a six-well plate (2.5 × 105 cells/well) and after 16 h transfect the cells with a 3′-Biotinylated control miRNA (celmiR-67) mimic (Bi-CTL) or 3′-Biotinylated miR-34a mimics (Bi-miR-34a) using Lipofectamine 2000 as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Final concentration of each biotinylated miRNA mimic is 20 nM.

3.2. Beads Preparation

After 24 h of transfection, activate the Streptavidin-Dyna beads by adding 100 μl beads (50 μl/pulldown) to a 1.5 ml eppendorf tube. Wash three times with 1 ml binding and washing buffer by holding the tube on the magnetic stand for 2 min.

Wash the activated beads twice with 1 ml Solution A followed by a wash with 1 ml Solution B. Resuspend the beads in 1 ml lysis buffer.

To reduce nonspecific binding, the beads should be coated with RNase-free BSA and yeast tRNA. Add 10 μl yeast tRNA (10 mg/ml stock), 10 μl BSA (10 mg/ml stock) and 480 μl lysis buffer to the beads and incubate at 4 °C for 30 min with rotation.

After the 30 min incubation, spin the beads at 500 ×g at 4 °C for 1 min to remove beads that adhere to the caps of the tube.

Wash the beads twice with 1 ml lysis buffer on the magnetic stand. The beads are now ready for the pulldowns.

3.3. Lysate Preparation

Twenty-four hour after transfection wash the cells twice with PBS (room temperature) and add 100 μl Trypsin-EDTA to each well. After 5 min incubation at 37 °C, add 500 μl cell culture medium to each well and transfer the cell suspension to a 15 ml falcon tube. Add 14 ml PBS to the cell suspension and spin at 500 × g for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and wash the cell pellet one more time with 15 ml PBS. Decant the supernatant and remove any remaining PBS with a p200 pipette.

To prepare cytoplasmic extract for the pulldowns, add 700 μl lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail and RNaseOUT to the cell pellet and transfer the lysate to a 1.5 ml eppendorf tube. Mix the lysate 20 times with a p1000 pipette and incubate on ice for 20 min.

Spin the lysate at 10,000 ×g at 4 °C for 15 min and collect the supernatant (cytoplasmic lysate) in a 1.5 ml eppendorf tube. Transfer 50 μl of the cytoplasmic lysate (input) into a fresh1.5 ml tube, add 200 μl lysis buffer followed by 750 μl Trizol LS. Mix by inversion and store at −80 °C.

3.4. Streptavidin Pulldowns

Incubate the cytoplasmic lysate (~600 μl) to the precoated beads and incubate (with rotation) at 4 °C for 4 h.

After the 4 h incubation, spin at 500 ×g for 1 min to remove beads that adhered to the cap of the tube. Place the tubes on the magnetic stand for 2 min and discard the supernatant. Add 1 ml lysis buffer to the beads and discard the supernatant after keeping the tubes on the magnetic stand for 2 min. Repeat the washing procedure four times to remove unbound material.

After the final wash, add 100 μl lysis buffer containing 5 μl of RNase-free DNase I (2 U/μl). Incubate at 37 °C for 10 min and discard the supernatant. Add 500 μl lysis buffer and discard the supernatant. This step will ensure degradation of genomic DNA contamination.

To the DNase-treated beads add 100 μl lysis buffer containing 5 μl Proteinase K (10 mg/ml) and 1 μl 10 % SDS. Incubate at 55 °C for 20 min, spin at 500 ×g for 1 min and collect the supernatant (~100 μl) on a magnetic stand. Add 200 μl of lysis buffer to the beads and collect the supernatant (200 μl). Combine the supernatants (~100 and 200 μl) and add 300 μl acid-phenol:chloroform. Proceed to RNA isolation.

3.5. RNA Isolation

Vortex the tubes for 1 min and spin at 10,000 × g at room temperature for 1 min. Collect 250 μl of upper layer and transfer to a fresh 1.5 ml tube. To precipitate the RNA, add 5 μl Glycoblue, 25 μl sodium acetate pH 5.2 and 625 μl 100 % prechilled ethanol. Mix by inversion and keep the tubes at −20 °C for 16 h. After 16 h, precipitate the RNA by centrifuging the tubes at 16,000 ×g for 30 min at 4 °C. Decant the supernatant, add 750 μL 70 % ethanol to the RNA pellet and precipitate the RNA by spinning the tubes at 7,500 ×g for 5 min at 4 °C. Decant the ethanol and carefully remove any residual ethanol near the pellet. Allow the pellet to air dry at room temperature for 5 min (do not allow the RNA pellet to over dry). Add 40 μl nuclease-free water to the pellet and dissolve the RNA by incubating on ice for 5–10 min.

To isolate RNA from input add 250 μl nuclease-free H2O to the Trizol LS containing lysate (Subheading 3.3) and vortex for 1 min after adding 200 μl chloroform. Spin at 12,500 ×g for 15 min and collect 400 μl upper layer in a 1.5 ml tube. Add 400 μl isopropanol, 5 μl Glycoblue and incubate at room temperature for 10 min. Spin the tubes for 15 min at 12,500 ×g at 4 °C. Discard the supernatant and wash the pellet by adding 1 ml 70 % chilled ethanol. Spin at 7,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Decant the ethanol and carefully remove any residual ethanol near the pellet. Allow the pellet to air dry at room temperature for 5 min (do not allow the RNA pellet to over dry). Add 40 μl nuclease-free water to the pellet and dissolve the RNA by incubating on ice for 5–10 min.

Quantitate the RNA using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer.

The isolated RNA is now ready for downstream analysis such as qRT-PCR or microarray.

3.6. Reverse Transcription and Real-Time PCR

Use 100 ng total RNA or 10 μl PD RNA for first-strand cDNA synthesis using iScript cDNA synthesis kit. Abundance of target mRNAs in the input or PD samples can be assessed by real-time PCR using SYBR Green master mix. We recommend measuring the levels of housekeeping mRNA such as GAPDH, SDHA, and UBC as negative controls. Primer sequences for qRT-PCR for these housekeeping genes have been previously described [21].

3.7. Concluding Remarks

The Biotin-miRNA pulldown method allows the experimental identification of direct miRNA targets. This approach can be used to validate putative targets of a miRNA and/or to discover novel miRNA targets.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

4 Notes

We recommend including a known miRNA or previously published miRNA (miR-34a or miR-519) as a positive control for the PD experiment. Optimizing the transfection conditions is important for the success of the PDs. We usually determine the transfection efficiency by transfecting the cells with a Cyclophilin B siRNA or control siRNA (Thermo Scientific) and measuring Cyclophilin B mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. For a majority of cell lines including HeLa, HCT116, DLD1 and H1299, we observe the ≥75 % knockdown of Cyclophilin B mRNA after 48 h of transfection. To ensure that the Bi-miRNA is functionally similar to the non-biotinylated miRNA, we recommend (1) testing the effect of the Bi-miRNA mimics and non-biotinylated miRNA mimics on the 3′ UTR of known targets by performing 3′ UTR luciferase reporter assays, (2) determining the effect of the Bi-miRNA mimics and nonbiotinylated miRNA mimics on the mRNA and protein levels of known target mRNAs. Once the conditions have been optimized and select known targets of the candidate miRNA are consistently enriched in the PDs, genome-wide mRNAs bound to the candidate miRNA can be identified by microarrays or RNA sequencing from the PD material. Because a significant proportion of miRNA targets are also down-regulated at the mRNA level [5, 24], microarrays should also be performed from the input samples. Performing microarrays from the input samples as well as the PD samples may help identify the mRNAs that are bound and also down-regulated. The mRNAs which are not down-regulated but are enriched in the PDs may be regulated at the level of mRNA translation.

References

- 1.Ambros V (2011) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431:350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berezikov E (2011) Evolution of microRNA diversity and regulation in animals. Nat Rev Genet 12:846–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R (2012) miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science 336:237–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baek D et al. (2008) The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455:64–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas M, Lieberman J, Lal A (2010) Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17:1169–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquinelli AE (2012) MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat Rev Genet 13: 271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelmohsen K et al. (2008) miR-519 reduces cell proliferation by lowering RNA-binding protein HuR levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:20297–20302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lytle JR, Yario TA, Steitz JA (2007) Target mRNAs are repressed as efficiently by microRNA-binding sites in the 5’ U T R as in the 3′ UTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 9667–9672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi SW, Hannon GJ, Darnell RB (2012) An alternative mode of microRNA target recognition. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeb GB et al. (2012) Transcriptome-wide miR-155 binding map reveals widespread non-canonical microRNA targeting. Mol Cell 48: 760–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lal A et al. (2009) miR-24 Inhibits cell proliferation by targeting E2F2, MYC, and other cell-cycle genes via binding to “seedless” 3′ UTR microRNA recognition elements. Mol Cell 35:610–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin C et al. (2010) Expanding the microRNA targeting code: functional sites with centered pairing. Mol Cell 38:789–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang TC et al. (2007) Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell 26:745–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson CD et al. (2007) The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res 67:7713–7722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim LP et al. (2005) Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433:769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beitzinger M et al. (2007) Identification of human microRNA targets from isolated argonaute protein complexes. RNA Biol 4:76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Easow G, Teleman AA, Cohen SM (2007) Isolation of microRNA targets by miRNP immunopurification. RNA 13:1198–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chi SW et al. (2009) Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature 460:479–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafner M et al. (2010) Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lal A et al. (2011) Capture of microRNA-bound mRNAs identifies the tumor suppressor miR-34a as a regulator of growth factor signaling. PLoS Genet 7:e1002363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdelmohsen K et al. (2012) Growth inhibition by miR-519 via multiple p21-inducing pathways. Mol Cell Biol 32:2530–2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang H et al. (2012) Bone morphogenetic protein 4 promotes vascular smooth muscle contractility by activating microRNA-21 (miR-21), which down-regulates expression of family of dedicator of cytokinesis (DOCK) proteins. J Biol Chem 287:3976–3986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selbach M et al. (2008) Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]