The liver is the second most frequently transplanted organ in the United States. In 2017, 8,082 transplantations were performed, and the number is increasing annually.1 Patient and graft survival rates after liver transplantation have typically been excellent. However, some people with advanced liver disease have no transplant center nearby.2 One metropolitan area lacking this access is El Paso, Texas (population, 833,592); the nearest transplant hospitals are hundreds of miles away in San Antonio, Dallas, and Houston.

Telemedicine uses electronic information and communication technology to provide and support health care when distance separates the participants. Telehealth encompasses telemedicine plus educational, research, and administrative applications.3 Its main principle is to disseminate these services from a central hub (typically, an academic medical center) to underserved areas within a geographic radius.

Although telehealth has been used extensively in various areas of health care, its only specific application to liver transplantation has involved care for transplant recipients as part of a small program at the University of Cincinnati. Two positive outcomes were noteworthy reductions in 30- and 90-day hospital readmission rates (50% and 33%, respectively), and high levels of patient satisfaction.4

The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) telehealth model, developed at the University of New Mexico, pairs hub-and-spoke telemedicine with the transmission of specialty knowledge and expertise to underserved locales. This model has been effective in the care of patients with liver disease. In a prospective study,5 investigators compared treatment outcomes in 2 groups: patients treated for hepatitis C by hepatologists at a large academic center, and patients similarly treated by primary care providers in rural areas and prisons participating in the ECHO program. Similar outcomes were reported after both groups underwent therapy with interferon and ribavirin—a complex regimen requiring experience and expertise to administer.5

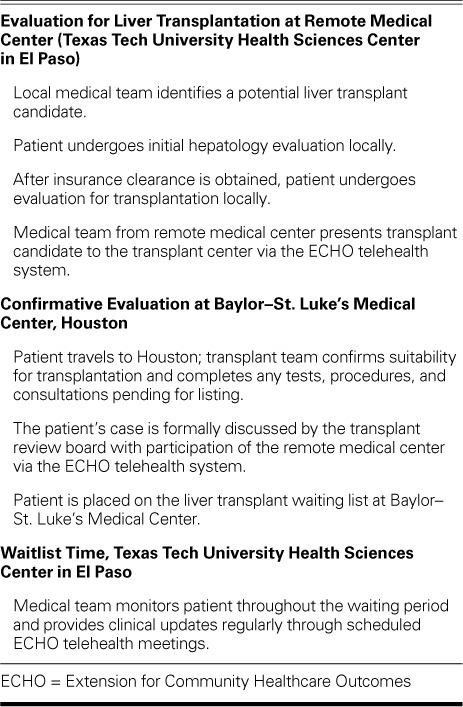

Recent collaboration between Baylor–St. Luke's Medical Center (which has a transplant center) and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in El Paso has resulted in a procedural framework for using the ECHO model in pre-liver transplant evaluation (Table I). We applied the ECHO model to liver transplant candidacy in El Paso. Thus far, of 3 patients fully evaluated in accordance with the model, 2 have been formally listed for transplantation. If not for this program, these patients might not have had access to transplantation.

TABLE I.

Telehealth Collaboration between Remote Medical Center and Transplant Center to Evaluate Liver Transplant Candidates

Even at this early stage, we have identified several benefits of using the ECHO telehealth model:

El Paso-area patients and their families have substantially less travel, in that only one visit to the transplant center is currently necessary during the evaluation process.

Patients have expressed great satisfaction after completing the pre-transplant medical requirements locally.

The El Paso medical providers have expressed great satisfaction after their active engagement in the pre-transplant evaluation and listing process.

The program's videoconferencing platform is easy to use.

El Paso physicians who have referred patients to this program have expressed their strong interest and support.

We foresee great value in continuing to use telehealth and the ECHO model in liver transplant evaluation and the care of transplant candidates. The main benefits are less travel, meaningful communication between transplant centers and local providers, and improvement in the specialty knowledge of local providers who treat patients with advanced liver disease.

References

- 1.Fayek SA, Quintini C, Chavin KD, Marsh CL. The current state of liver transplantation in the United States: perspective from American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS) Scientific Studies Committee and endorsed by ASTS Council. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(11):3093–104. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilder JM, Oloruntoba OO, Muir AJ, Moylan CA. Role of patient factors, preferences, and distrust in health care and access to liver transplantation and organ donation. Liver Transpl. 2016;22(7):895–905. doi: 10.1002/lt.24452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serper M, Volk ML. Current and future applications of telemedicine to optimize the delivery of care in chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(2):157–61.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ertel AE, Kaiser T, Shah SA. Using telehealth to enable patient-centered care for liver transplantation. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(7):674–5. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]