Abstract

Infections from coxsackie B2 viruses often cause viral myocarditis and, only rarely, multisystem organ impairment. We present the unusual case of a 42-year-old man in whom coxsackie B2 virus infection caused multiorgan infection, necessitating distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, renal dialysis, and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with mechanical ventilation. In addition, the patient had a rapid-eye-movement sleep–related conduction abnormality that caused frequent sinus pauses of longer than 10 s, presumably due to myocarditis from the coxsackievirus infection. He recovered after permanent pacemaker placement and was discharged from the hospital. We discuss our aggressive supportive care and the few other reports of multiorgan impairment from coxsackieviruses.

Keywords: Acute disease; coxsackievirus infections/complications/diagnosis/pathology; disease progression; multiple organ failure/etiology; myocarditis/complications/etiology/pathology; pancreatitis/complications; sinus arrest, cardiac/physiopathology; sleep, REM; treatment outcome; virus diseases/complications

Coxsackie B virus (CVB) infections usually involve a single organ, such as the pancreas or heart; rarely, they affect 2 organs. We present the case of a patient in whom coxsackie B2 virus (CVB2) infection caused widespread multiorgan impairment, including cardiogenic shock complicated by a conduction disorder, and we discuss our treatment decisions.

Case Report

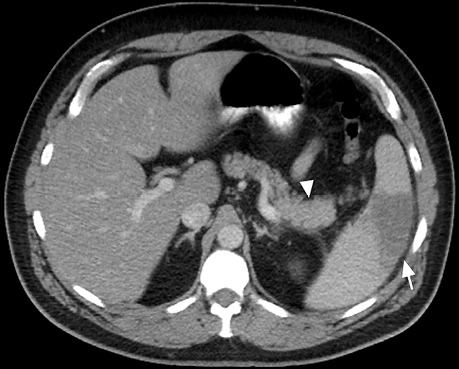

In summer 2016, a 42-year-old man with a history of obstructive sleep apnea presented with a 7-day history of vague abdominal pain followed by a 3-day history of worsening high-grade fever, malaise, and sharp abdominal pain. His blood pressure and laboratory values were normal, except for lactate dehydrogenase (mildly elevated at 272 U/L) and a platelet count of 110 ×109/L. An abdominal computed tomogram revealed pancreatic heterogeneity, peripancreatic lymphadenopathy, and splenic infarction (Fig. 1). Our initial diagnosis was focal severe pancreatitis, complicated by worsening acute renal insufficiency, which indicated the possibility of glomerulonephritis. Results of urinalysis and renal ultrasound were nondiagnostic. Initial therapy included intravenous fluids and avoidance of nephrotoxic agents. Approximately one week after hospital admission, the patient underwent distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes; substantial intra-abdominal inflammation precluded a renal biopsy.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomogram upon admission shows focal pancreatic inflammation (arrow) and concomitant splenic infarction (arrowhead).

Postoperatively, the patient's fever persisted. Acute dyspnea developed, accompanied by electrocardiographic changes consistent with inferolateral myocardial injury or myopericarditis (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the patient had an elevated serum troponin level of >73 ng/mL associated with a peak creatine kinase-MB level of 540 ng/mL. Coronary catheterization revealed no substantial coronary artery disease but did show markedly elevated filling pressures with reduced cardiac output, which necessitated the placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump. Diuresis and milrinone therapy were also begun. Transthoracic echocardiograms suggested a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 0.15, and the diagnosis was acute fulminant myocarditis resulting in acute systolic heart failure.

Fig. 2.

Electrocardiogram upon onset of dyspnea shows PR-segment depression and ST-segment elevation in leads II, III and aVF, consistent with myocardial ischemia.

The patient's worsening cardiac status was complicated by pulmonary edema and oliguric renal failure. After 2 days, his therapy was escalated to venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), mechanical ventilation, and continuous renal replacement therapy. Within 5 days, his cardiopulmonary hemodynamic status improved enough to enable both decannulation from VA-ECMO and extubation, and dialysis was discontinued soon thereafter when his renal function recovered. An echocardiogram after decannulation confirmed a mildly depressed LVEF of 0.50.

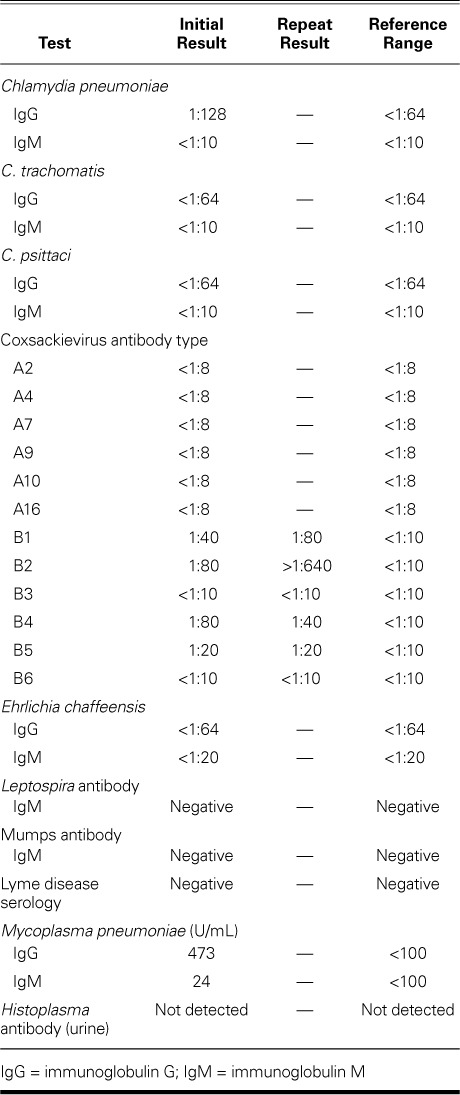

Pancreatic biopsy specimens revealed lymphoid proliferation, inflammation, and focal necrotic fibrosis; results of a splenic biopsy confirmed infarction and inflammation; and peripancreatic lymph node specimens were reactive. Cardiac biopsy results included inflammation but no infarction or necrosis; the diagnostic value was limited because the sample had been obtained from atrial tissue during VA-ECMO cannulation. An extensive multidisciplinary diagnostic evaluation of immunologic and infectious factors was performed (Table I). Previous exposure to Mycoplasma pneumoniae was detected. Of note, the CVB2 antibody titer was initially positive at 1:80 (normal, <1:10); 21 days later, it substantially increased to >1:640.

TABLE I.

Results of Tests for Immunologic and Infectious Factors

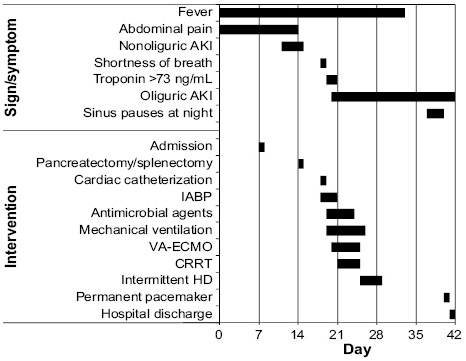

The patient's hospital course was further complicated by frequent, prolonged (>10 s) episodes of sinus arrest during later stages of sleep. These were not associated with obstructive sleep apnea (the patient was using his continuous positive airway pressure unit, at usual settings) or with hypoxia, as confirmed by nocturnal continuous oximetry readings. The pauses also occurred in the stepdown unit, where the patient got normal hours of sleep. Cardiac electrophysiologists recommended permanent pacemaker implantation, which was done, and the patient was discharged from the hospital in stable condition after a total stay of 42 days (Fig. 3). Follow-up interrogations of the pacemaker revealed no pacing requirements. The patient ultimately underwent orthotopic heart transplantation and, as of November 2018, was doing well.

Fig. 3.

Graph shows the patient's hospital course. Bars indicate the time of onset and duration of the symptom or intervention.

AKI = acute kidney injury; CRRT = continuous renal replacement therapy; HD = hemodialysis; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump; VA-ECMO = venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Discussion

Coxsackievirus B, a well-known cause of myocarditis, also causes pancreatitis, hepatitis, skin rashes, aseptic meningitis,1–5 and acute renal failure.6–10 The link between coxsackieviruses and kidney injury is less well established; however, coxsackieviruses have also led to acute glomerulonephritis8,9 and infection of mesangial cells.10 Although multiorgan involvement of CVB is very rare, infants have died of multiorgan failure,11,12 a previously healthy adult patient had cardiac tamponade caused by myopericarditis and died of multiorgan failure,13 and a renal transplant patient had pancreatitis and myocarditis.14 Two cases of cardiac, pancreatic, and hepatic (triple) involvement have been reported—one caused by CVB215 and the other by coxsackievirus A4.4 Another patient had myopericarditis, pleuritis, and acute liver failure caused by CVB, with elevated titers of serotypes CVB1, -2, and -6.16 Our patient's case is unusual not only because of the organ systems involved, but also the complex sequence of organ involvement, from pancreas and spleen to kidneys and heart. Although some of the earlier patients also had substantial disease processes (particularly in compromised hosts, unlike our patient), aggressive intervention ultimately enabled their recovery. Finally, our patient's illness resulted in a conduction system abnormality associated with rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep that was due presumably to severe acute myocarditis.

Our patient's positive CVB2 titer (initially 1:80) was 4 times normal. Its increase to >1:640 indicated acute infection. The weakly positive titers of serotypes CVB1, -2, -4, and -5 indicated cross-reactivity, which is also consistent with acute CVB infection.

A similar sequential progression of symptoms has been reported.15 Coxsackieviruses are known to have a multiphasic course: Zaoutis and Klein2 called the initial organ-seeding infection “minor viremia” and replication within those organs “major viremia.” In addition, experiments involving mice inoculated with CVB strains produced pancreatitis, followed by myocarditis.11 Given the lack of other reasonable causes in our patient (nondiagnostic urinalysis and renal ultrasound, no hypotension, and nothing apparent on the initial computed tomogram with contrast medium), we think that his initial renal insufficiency was also due to CVB2.6–10 The renal insult was certainly exacerbated by the cardiogenic shock later in his hospital course.

Currently, the treatment of coxsackievirus infection mainly constitutes supportive measures, and indeed our patient recovered rapidly after aggressive supportive care. Of importance, the use of VA-ECMO that ultimately enabled his recovery is well established as temporary support for shock in the presence of acute fulminant myocarditis; it enables substantial recovery of LVEF and favorable long-term outcomes.17,18

Last, our patient's frequent episodes of sinus arrest lasted >10 s but occurred only while he slept. They persisted despite optimal continuous positive airway pressure therapy and were not associated with hypoxia. Because the pauses occurred unprovoked, only during sleep, and always in the early morning, we think that they were associated with REM sleep. As in other patients with REM-related bradyarrhythmias, daytime telemetry readings and electrocardiograms showed nothing unusual.19 The prevalence of REM-related bradyarrhythmia is unknown; however, the condition is thought to be rare, and it is typically detected during unrelated monitoring.19,20 The most likely cause of REM-related sinus arrest is vagal overactivity and hyperactivation of baroreceptors that create abnormal autonomic regulation of the cardiovascular system. Among the few case descriptions, REM-related sinus arrest seems to be prevalent in young and middle-aged men.15

Cardiac conduction system abnormalities, including sinoatrial and atrioventricular conduction block of varying severity, are a known complication of some forms of myocarditis, typically Lyme carditis, cardiac sarcoidosis, and idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis.21–23 Although our patient's cardiac tissue specimen was not specifically tested for CVB, the conduction abnormality was probably caused by myocardial injury. To our knowledge, a REM-related conduction abnormality secondary to CVB myocarditis has not been described. We consider it unlikely that our patient's sinus arrests were an incidental finding, because previous sleep studies for his obstructive sleep apnea had not revealed them. They were possibly related to an indolent sinoatrial conduction abnormality caused by recent acute myocarditis and were unmasked during REM sleep, especially given that they occurred when the patient had finally achieved optimal, normal sleep patterns and had improved overall as the myocarditis resolved. This conclusion is supported by the results of pacemaker interrogations, which revealed no pacing requirements after his discharge from the hospital.

This is an unusual case of CVB2 infection, perhaps a first, in an adult patient who presented with the reported sequence of multisystem organ involvement, responded to organ-supportive therapy, and needed permanent pacemaker therapy.

References

- 1.Moore M, Kaplan MH, McPhee J, Bregman DJ, Klein SW. Epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory features of coxsackie B1-B5 infections in the United States, 1970–79. Public Health Rep. 1984;99(5):515–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaoutis T, Klein JD. Enterovirus infections. Pediatr Rev. 1998;19(6):183–91. doi: 10.1542/pir.19-6-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracy S, Gauntt C. Group B coxsackievirus virulence. Curr Top Microbiology Immunol. 2008;323:49–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75546-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akuzawa N, Harada N, Hatori T, Imai K, Kitahara Y, Sakurai S, Kurabayashi M. Myocarditis, hepatitis, and pancreatitis in a patient with coxsackievirus A4 infection: a case report. Virol J. 2014;11:3. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith WG. Coxsackie B myopericarditis in adults. Am Heart J. 1970;80(1):34–46. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(70)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aronson MD, Phillips CA. Coxsackievirus B5 infections in acute oliguric renal failure. J Infect Dis. 1975;132(3):303–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/132.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fodili F, van Bommel EF. Severe rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure following recent Coxsackie B virus infection. Neth J Med. 2003;61(5):177–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayatpour M, Zbitnew A, Dempster G, Miller KR. Role of coxsackievirus B4 in the pathogenesis of acute glomerulonephritis. Can Med Assoc J. 1973;109(9):873. passim. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papachristou F, Printza N. Acute nephritis complicating Coxsackie B infection. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42(8):838–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasch A, Frey FJ. Coxsackie B viruses and the kidney--a neglected topic. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(5):1184–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tracy S, Hofling K, Pirruccello S, Lane PH, Reyna SM, Gauntt CJ. Group B coxsackievirus myocarditis and pancreatitis: connection between viral virulence phenotypes in mice. J Med Virol. 2000;62(1):70–81. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200009)62:1<70::aid-jmv11>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau G. Acute fulminant, fatal coxsackie B virus infection: a report of two cases. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(6):917–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorenbeyn A, Smally AJ. A rare case of concomitant viral myocarditis and pericarditis in a 44-year-old patient. J Emerg Med. 2004;27(4):355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pretagostini R, Lai Q, Pettorini L, Garofalo M, Poli L, Melandro F et al. Multiple organ failure associated with coxsackie virus in a kidney transplant patient: case report. Transplant Proc. 2016;48(2):438–40. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coplan NL, Atallah V, Mediratta S, Bruno MS, DePasquale NP. Cardiac, pancreatic, and liver abnormalities in a patient with coxsackie-B infection. Am J Med. 1996;101(3):325–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaheeruddin S, Bade NA, Jani S, Srichai MB. A case of coxsackie B virus infection leading to multi-organ inflammation: myopericarditis and acute liver failure. Case Rep Intern Med. 2014;1(2):45–50. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ac66/d52c4b8ba056acbcc7063734f71525258b08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll BJ, Shah RV, Murthy V, McCullough SA, Reza N, Thomas SS et al. Clinical features and outcomes in adults with cardiogenic shock supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(10):1624–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy RE, 3rd, Boehmer JP, Hruban RH, Hutchins GM, Kasper EK, Hare JM, Baughman KL. Long-term outcome of fulminant myocarditis as compared with acute (nonfulminant) myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(10):690–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holty JE, Guilleminault C. REM-related bradyarrhythmia syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15(3):143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serafini A, Dolso P, Gigli GL, Fratticci L, Cancelli I, Facchin D et al. REM sleep brady-arrhythmias: an indication to pacemaker implantation? Sleep Med. 2012;13(6):759–62. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Linde MR. Lyme carditis: clinical characteristics of 105 cases. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1991;77:81–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapelon-Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, Veyssier P, Wechsler B, Huong DL et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83(6):315–34. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000145367.17934.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper LT, Jr, Berry GJ, Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis--natural history and treatment. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(26):1860–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]