Abstract

Activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) enhances sensory–cognitive function in human subjects and animal models, yet the neural mechanisms are not fully understood. This review summarizes recent studies on nicotinic regulation of neural processing in the cerebral cortex that point to potential mechanisms underlying enhanced cognitive function. Studies from our laboratory focus on nicotinic regulation of auditory cortex and implications for auditory–cognitive processing, but relevant emerging insights from multiple brain regions are discussed. Although the major contributions of the predominant nAChRs containing α7 (homomeric receptors) or α4 and β2 (heteromeric) subunits are well recognized, recent results point to additional, potentially critical contributions from α2 subunits that are relatively sparse in cortex. Ongoing studies aim to elucidate the specific contributions to cognitive and cortical function of diverse nAChRs.

Implications

This review highlights the therapeutic potential of activating nAChRs in the cerebral cortex to enhance cognitive function. Future work also must determine the contributions of relatively rare but important nAChR subtypes, potentially to develop more selective treatments for cognitive deficits.

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Regulate Cognitive and Cortical Functions

Nicotine enhances sensory–cognitive functions via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) that also are activated by attention-related release of the endogenous neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. Performance on sensory-related tasks is improved by nicotine and, conversely, impaired by nicotinic antagonists, genetic deletion of nAChRs, or disease-induced loss of nAChRs.1–6 Similarly, for decades it has been known that nicotine enhances cognitive and cortical functions more broadly, as evidenced by studies that focus on, for example, learning and memory, attention, and cortical neurophysiology.2–5,7,8 In animal models, systemic nicotine enhances working memory, reference memory, memory acquisition, memory restitution, and associative learning.5,9–12 Attention-related studies, such as those that measure readiness to detect brief sensory signals at unpredictable intervals, also reveal increased accuracy with nicotine.7 In human subjects, including both smokers and nonsmokers, nicotine (eg, via transdermal patch) can improve working memory.5 Although enhanced performance in smokers can be partly attributed to relief from nicotine withdrawal (induced by abstinence before testing), studies show enhanced function in nonsmokers as well.5 Nicotine also affects cortical neurophysiology in a manner consistent with enhanced cognition. For example, in electroencephalogram studies nicotine increases spectral power at frequencies associated with arousal while decreasing power at frequencies associated with a relaxed state.13 Similarly, in studies utilizing functional magnetic resonance imaging, nicotine increases activation of frontal networks during attention-related tasks.13 Thus, physiological and behavioral studies consistently show that activation of nAChRs can enhance sensory–cognitive function.

It is generally assumed that pro-cognitive effects of nicotine depend on activating nAChRs associated with central cholinergic systems that mediate attention and other higher brain functions.14 Nucleus basalis cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain innervate neocortical regions and release acetylcholine that binds to cortical nAChRs (and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors) to enhance cortical function.15 In sensory and nonsensory cortex, nAChRs are found presynaptically on terminals of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, including, in some cases, the terminals of thalamocortical projection neurons (Figure 1).16–18 Activation of presynaptic nAChRs on axon terminals can enhance synaptic transmission by increasing neurotransmitter release.19,20 Enhanced sensory thalamocortical transmission also may involve nAChRs located in the subcortical white matter, where they act to enhance the speed and synchrony of axonal propagation.17,21,22 Postsynaptic nAChRs also occur throughout cortex and act to increase excitability.16,23–26 However, actions of nAChRs to excite inhibitory interneurons are particularly prominent in studies of hippocampus and sensory cortex, and can both inhibit pyramidal (principal) neurons as well as increase responsiveness of pyramidal neurons by inhibiting other interneurons that mediate feed-forward inhibition.23–25,27 Thus, nAChRs can be presynaptic, postsynaptic, pre-junctional, and axonal, and located on both excitatory and inhibitory neurons (Figure 1). A challenge for future research will be to understand how diverse nicotinic actions integrate to enhance cortical and cognitive functions.

Figure 1.

Overview schematic of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR)-mediated regulation of diverse types of neurons and afferent inputs in prefrontal cortex. LI–LVI, cortical layers 1 through 6. From Poorthuis et al..16

Because activation of nAChRs enhances cognitive functions generally, nicotinic agonists (including nicotine itself) are being tested as potential therapeutic treatments for cognitive disorders in adults, especially those that involve diminished attention, learning, and memory.14,28–30 In patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment, nicotine and related agents improve cognitive outcomes, including the acquisition and retention of visual and verbal information, decreased errors, and improved performance of cognitively demanding tasks.8,28 For adults with attention deficit disorders, nicotinic agonists moderately improve symptoms.5,30 In patients with schizophrenia, nicotine improves cognitive functioning such as spatial processing in smokers and attention in both smoking and nonsmoking patients.5,28 The use of nicotine, delivered via transdermal patch or gum, as a potential therapeutic for enhancing cognition naturally raises concerns about potential misuse or abuse, remission, and addiction liability. Yet, existing evidence suggests that nicotine, when delivered topically (patch) or orally (gum), apparently does not lead to dependence, as very few people use nicotine gum for non-cessation purposes.31 However, the best approach to address addiction liability of nicotine replacement therapy is to test its long-term administration on nonsmoking participants. In a study by Newhouse et al.,8 nonsmoking elderly adults with mild cognitive impairment were administered 15 mg/day of nicotine via transdermal patch over a period of 6 months. After completion of the study, none of the participants experienced withdrawal symptoms, and none continued nicotine use.8 Also important for long-term use, nicotine’s efficacy for improving memory does not decrease over time.5 These results highlight the promise of nicotinic agents as therapeutics and the importance of developing agents that do not lead to dependence and other adverse side effects. Optimization of nicotinic treatments for cognitive disorders, including the use of subtype-specific nicotinic agonists,32 will require a comprehensive knowledge of nAChR composition and distribution, and an understanding of their integrated effects on neural systems.

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

nAChRs are the prototypic ionotropic receptor and bind the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.23,33 The receptor comprises five subunits arranged around a pore that functions as an ion channel. Neuronal subtypes of nAChRs are either homomeric with five α subunits or heteromeric with a combination of α and β subunits from two subfamilies, α2 through α10 and β2 through β4.23,33,34 Expression of nAChRs in Xenopus oocytes has revealed the consequences of different combinations of α and β subunits on receptor function, including ion permeability, notably to Ca2+, and channel kinetics.23,33,35 The predominant subtypes in the brain are homomeric α7 nAChRs, which have low affinity for nicotine, and heteromeric α4β2* nAChRs that bind nicotine with high affinity (the asterisk represents possible additional, accessory subunits that can alter function23,33,35). The large majority (90%) of nAChRs in the cerebral cortex are α4β2* or α7.36,37 Additional subunits, such as α2 (see below) or α5, are found in cortex at low levels37 but may contribute critically to certain functions. For example, in prefrontal cortex, inclusion of an α5 subunit reduces receptor desensitization26 and is required for attentional performance under challenging conditions.37,38

As these results illustrate, the diversity of nAChR function conferred by receptor location (pre- and postsynaptic; excitatory and inhibitory neurons) is multiplied by the diversity of nAChR subtypes. This complexity is illustrated in Figure 1, which depicts locations and subunit composition of nAChRs in prefrontal cortex.16 Additional characteristics of nAChRs that affect synaptic transmission and modulation are receptor desensitization (decreased response in the continued presence of agonist) and upregulation (increased receptor number after chronic exposure to agonist).34 Thus, a full understanding of therapeutic nicotinic regulation will require integrating the contributions of diverse nAChRs with varying subunit composition, distribution, and response to chronic use of agonist.

Spectral Integration and Functions of nAChRs in Auditory Cortex

It is useful to consider nicotinic regulation of auditory–cognitive function within a framework of spectral integration of afferent inputs to primary auditory cortex (A1). Spectral integration involves interconnecting frequency representations to allow for processing of spectrally complex stimuli. Although extracellular recordings indicate a relatively constant breadth of suprathreshold frequency receptive fields (ie, those based on action potential recordings) throughout the main (lemniscal) ascending auditory pathways,39 other studies show that single neurons within A1 receive subthreshold inputs across a much broader range of frequencies.40–42 The integration of spectral inputs via intracortical processing is hypothesized to be modulated by behavioral state (eg, sleep, waking, and attention) and experience, resulting in dynamic changes to receptive fields.42 As these mechanisms mediate sensitivity to both complex stimuli and top–down regulation from higher cortical regions, a detailed understanding of nicotinic modulation, including the location and function of relevant nAChR subtypes, may permit targeted therapies for specific sensory–cognitive deficits.

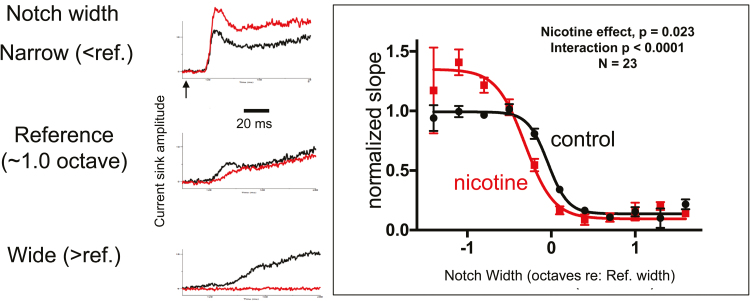

Activation of nAChRs is known to enhance sensory–cognitive function in auditory (and other sensory) systems because performance on auditory tasks is improved by nicotine and, conversely, impaired by nicotinic antagonists, genetic deletion of nAChRs, or disease-induced loss of nAChRs.1–6 Although the precise functions regulated by nAChRs are not fully understood, a recurring hypothesis is that nicotine improves “attentional narrowing” to focus attention on relevant acoustic stimuli, including speech.43–46 In auditory cortex, systemic nicotine enhances neural processing, producing narrower receptive fields with increased gain (Figure 2).22,41,47 This effect mimics that of auditory selective attention,48–50 and likely contributes to nicotine-induced auditory–cognitive enhancement. Although nicotine is delivered systemically, the locus of excitatory action is within A1 and the auditory thalamocortical pathway, as the excitatory effects of systemic nicotine are blocked by local injection of the antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine and mimicked by local injection of agonist or a positive allosteric modulator.22,41,47 Inhibitory effects of systemic nicotine also are seen in A1, as well as the auditory midbrain and thalamus.22 Although effect of dihydro-β-erythroidine has been interpreted as implicating α4β2* nAChRs, given their predominance in cortex, dihydro-β-erythroidine also binds to α2β2 nAChRs,51 and their contributions cannot be precluded. Potential functional consequences of nAChRs containing α2 subunits will be discussed next.

Figure 2.

Systemic nicotine enhances gain and narrows receptive fields in mouse A1. Left: Example traces are current sinks in layer 4 of anesthetized mice, recorded using a 16-channel linear probe and evoked by acoustic “notched-noise” stimuli centered at the characteristic frequency (CF) (ie, white noise filtered to remove a spectral “notch” centered at CF for the recording site). Current sinks reflect stimulus-evoked synaptic activity at the recording site. Example shows that a narrow-notch stimulus that activates most of the receptive field produces a robust current sink (top black trace) that is enhanced by systemic nicotine (2 mg/kg), indicating increased gain. A wide-notch stimulus that activates only the edges of the receptive field produces a weaker response that is abolished by nicotine (bottom), indicating narrowing of the receptive field by nicotine. Right: group data from current-source density recordings in 23 mice plotting the initial slope of layer 4 current sink versus notch width of stimulus (normalized to a reference width that elicits the half-max response in each animal). Systemic nicotine enhances gain (curve shifts to higher values) and narrows receptive fields (curve shifts to narrower notch widths). Modified from Askew et al..22

Potential Contributions to Cortical Function of α2-Containing nAChRs

Recently, several studies have suggested a role in cortical function for nAChRs containing α2 subunits, serving to emphasize the possibility that even nAChR subunits that are relatively sparse (<3% of cortical nAChR subunits for α237) may play an important functional role. Historically, α2 subunit was among the first neuronal nAChR subunits studied after co-expression with β2 subunits.52 However, because of its relatively low levels in cortex and the pharmacological properties it shares with the ubiquitous α4 subunit, most studies have focused on the latter.52 Both α2 and α4 subunits are agonist-binding subunits that form functional receptors with β2 subunits.53 In comparing α2 and α4 subunits, several differences emerge.36,53 Whereas α4 subunits are expressed in all cortical layers and in hippocampus, α2 subunits are expressed sparsely (in rodent) yet selectively in cortical layers 5 and 6, and in a subpopulation of hippocampal interneurons (oriens-lacunosum moleculare interneurons). Importantly, however, α2 nAChRs appear to be highly expressed in nonhuman primate cortex54 and in human cortex,55 leading to the speculation that evolutionary pressure has resulted in increased expression of α2 nAChRs in cortex.54

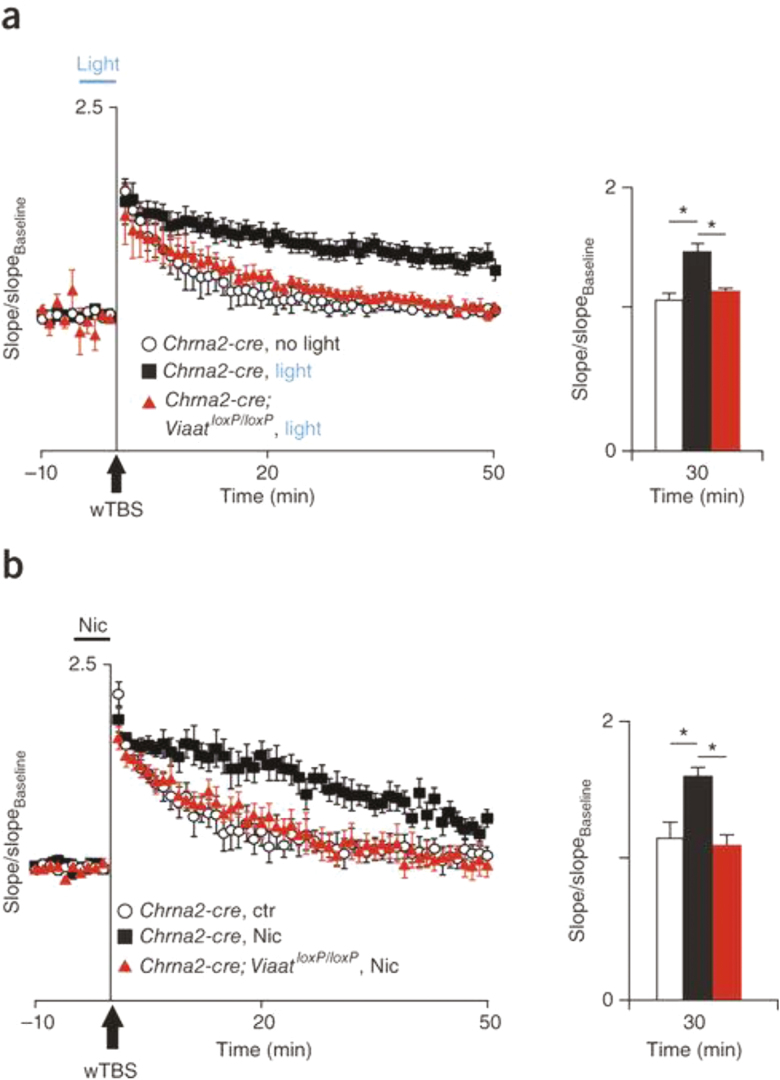

Recent studies in mouse have revealed an important role for α2-expressing interneurons in hippocampal function including long-term potentiation (LTP), a putative cellular mechanism of learning and memory.56–59 In hippocampal slices, whole-cell recordings show that presumed oriens-lacunosum moleculare interneurons discharge continuously (without desensitization) during application of nicotine, and single-cell reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis indicates that these cells express α2 subunits.57 The results suggest that sustained activation of α2 nAChRs produces continuous firing of oriens-lacunosum moleculare interneurons.57 These α2 nAChR-expressing interneurons regulate the production of LTP.56,60 Nicotinic facilitation of LTP in the Schaffer collateral input to CA1 is abolished in mutant mice lacking α2 nAChRs56 and enhanced in mice with “hypersensitive” α2 nAChRs (serine for leucine substitution resulting in 100-fold increased sensitivity).59 Similarly, optogenetic activation of α2 nAChR-expressing neurons enhances LTP, whereas loss of α2 nAChR-mediated function abolishes nicotinic enhancement of LTP (Figure 3).60 Finally, behavioral studies show that genetic deletion of α2 nAChRs impairs hippocampal-dependent spatial memory.58

Figure 3.

Activation of α2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR)-expressing inhibitory interneurons enhances long-term potentiation (LTP) in hippocampal slices. (a) Potentiation of Schaffer collateral synapses in Chrna2-cre and Chrna2-cre;ViaatloxP/loxP mice with Cre recombinase-induced expression of channelrhodopsin in control conditions (no light) and with a light pulse applied 5 minutes before and during Schaffer collateral weak theta-burst stimulation (wTBS; subthreshold for LTP). Bar graphs show the mean normalized slope 30 minutes after wTBS. (b) Data are presented in (a), but with 1 μM bath-applied nicotine instead of light stimulation. Chrna2-cre, mouse line expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Chrna2 promoter. Chrna2-cre;ViaatloxP/loxP, mouse line with inhibition from α2 nAChR-expressing cells abolished by crossing Chrna2-cre mice with mice carrying a loxP-flanked Viaat allele. From Leão et al..60

These recent studies indicate that even relatively sparse α2 nAChRs may play an important role in nicotinic regulation of cortical function and highlight the potential usefulness of targeting understudied nAChR subunits. Overall, an understanding of the distinct contributions made by diverse nAChRs may lead to novel treatments targeting diverse forms of cognitive disorders.

Funding

Work from our laboratory was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DC013200, P30 DC08369, T32 DC010775) and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (under DGE-1321846).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Warburton DM. Nicotine as a cognitive enhancer. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1992;16(2):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Terry AV Jr, Buccafusco JJ, Jackson WJ, Zagrodnik S, Evans-Martin FF, Decker MW. Effects of stimulation or blockade of central nicotinic-cholinergic receptors on performance of a novel version of the rat stimulus discrimination task. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1996;123(2):172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Evans DE, Drobes DJ. Nicotine self-medication of cognitive-attentional processing. Addict Biol. 2009;14(1):32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sarter M, Parikh V, Howe WM. nAChR agonist-induced cognition enhancement: integration of cognitive and neuronal mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78(7):658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3–4):523–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horst NK, Heath CJ, Neugebauer NM, Kimchi EY, Laubach M, Picciotto MR. Impaired auditory discrimination learning following perinatal nicotine exposure or β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit deletion. Behav Brain Res. 2012;231(1):170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grilly DM. A verification of psychostimulant-induced improvement in sustained attention in rats: effects of d-amphetamine, nicotine, and pemoline. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newhouse P, Kellar K, Aisen P, et al. Nicotine treatment of mild cognitive impairment: a 6-month double-blind pilot clinical trial. Neurology. 2012;78(2):91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. French KL, Granholm AC, Moore AB, Nelson ME, Bimonte-Nelson HA. Chronic nicotine improves working and reference memory performance and reduces hippocampal NGF in aged female rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169(2):256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arendash GW, Sanberg PR, Sengstock GJ. Nicotine enhances the learning and memory of aged rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;52(3):517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riekkinen M, Riekkinen P Jr. Nicotine and D-cycloserine enhance acquisition of water maze spatial navigation in aged rats. Neuroreport. 1997;8(3):699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Socci DJ, Sanberg PR, Arendash GW. Nicotine enhances Morris water maze performance of young and aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(5):857–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansvelder HD, van Aerde KI, Couey JJ, Brussaard AB. Nicotinic modulation of neuronal networks: from receptors to cognition. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3–4):292–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crooks PA, Bardo MT, Dwoskin LP. Nicotinic receptor antagonists as treatments for nicotine abuse. Adv Pharmacol. 2014;69:513–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wenk GL. The nucleus basalis magnocellularis cholinergic system: one hundred years of progress. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1997;67(2):85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poorthuis RB, Bloem B, Schak B, Wester J, de Kock CP, Mansvelder HD. Layer-specific modulation of the prefrontal cortex by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(1):148–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kawai H, Lazar R, Metherate R. Nicotinic control of axon excitability regulates thalamocortical transmission. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1168–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Differential regulation of neocortical synapses by neuromodulators and activity. Neuron. 1997;19(3):679–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGehee DS, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269(5231):1692–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Girod R, Barazangi N, McGehee D, Role LW. Facilitation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(13):2715–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mukherjee J, Lao PJ, Betthauser TJ, et al. Human brain imaging of nicotinic acetylcholine α4β2* receptors using [18 F]Nifene: selectivity, functional activity, toxicity, aging effects, gender effects, and extrathalamic pathways. J Comp Neurol. 2018;526(1):80–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Askew C, Intskirveli I, Metherate R. Systemic nicotine increases gain and narrows receptive fields in A1 via integrated cortical and subcortical actions. eNeuro. 2017;4(3):e0192-17.2017 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):73–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pi HJ, Hangya B, Kvitsiani D, Sanders JI, Huang ZJ, Kepecs A. Cortical interneurons that specialize in disinhibitory control. Nature. 2013;503(7477):521–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Porter JT, Cauli B, Tsuzuki K, Lambolez B, Rossier J, Audinat E. Selective excitation of subtypes of neocortical interneurons by nicotinic receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19(13):5228–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Poorthuis RB, Bloem B, Verhoog MB, Mansvelder HD. Layer-specific interference with cholinergic signaling in the prefrontal cortex by smoking concentrations of nicotine. J Neurosci. 2013;33(11):4843–4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takesian AE, Bogart LJ, Lichtman JW, Hensch TK. Inhibitory circuit gating of auditory critical-period plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(2):218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Newhouse PA, Potter A, Singh A. Effects of nicotinic stimulation on cognitive performance. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4(1):36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gold M, Newhouse PA, Howard D, Kryscio RJ. Nicotine treatment of mild cognitive impairment: a 6-month double-blind pilot clinical trial. Neurology. 2012;78(23):1895; author reply 1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Potter AS, Newhouse PA. Acute nicotine improves cognitive deficits in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88(4):407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hughes JR, Pillitteri JL, Callas PW, Callahan R, Kenny M. Misuse of and dependence on over-the-counter nicotine gum in a volunteer sample. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taly A, Corringer PJ, Guedin D, Lestage P, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(9):733–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ortells MO, Barrantes GE. Tobacco addiction: a biochemical model of nicotine dependence. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74(5):884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mazzaferro S, Bermudez I, Sine SM. α4β2 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: relationships between subunit stoichiometry and function at the single channel level. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(7):2729–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wada E, Wada K, Boulter J, et al. Distribution of alpha 2, alpha 3, alpha 4, and beta 2 neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in the central nervous system: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;284(2):314–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mao D, Perry DC, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ. The alpha4beta2alpha5 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is resistant to up-regulation by nicotine in vivo. J Neurochem. 2008;104(2):446–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bailey CD, De Biasi M, Fletcher PJ, Lambe EK. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha5 subunit plays a key role in attention circuitry and accuracy. J Neurosci. 2010;30(27):9241–9252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Calford MB, Webster WR, Semple MM. Measurement of frequency selectivity of single neurons in the central auditory pathway. Hear Res. 1983;11(3):395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaur S, Lazar R, Metherate R. Intracortical pathways determine breadth of subthreshold frequency receptive fields in primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(6):2551–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Intskirveli I, Metherate R. Nicotinic neuromodulation in auditory cortex requires MAPK activation in thalamocortical and intracortical circuits. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107(10):2782–2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Metherate R, Kaur S, Kawai H, Lazar R, Liang K, Rose HJ. Spectral integration in auditory cortex: mechanisms and modulation. Hear Res. 2005;206(1–2):146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Trimmel M, Wittberger S. Effects of transdermally administered nicotine on aspects of attention, task load, and mood in women and men. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78(3):639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Friedman J, Horvath T, Meares R. Tobacco smoking and a ‘stimulus barrier’. Nature. 1974;248(447):455–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Knott VJ, Bolton K, Heenan A, Shah D, Fisher DJ, Villeneuve C. Effects of acute nicotine on event-related potential and performance indices of auditory distraction in nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(5):519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kassel JD. Smoking and attention: a review and reformulation of the stimulus-filter hypothesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17(5):451–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kawai HD, Kang HA, Metherate R. Heightened nicotinic regulation of auditory cortex during adolescence. J Neurosci. 2011;31(40):14367–14377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okamoto H, Stracke H, Wolters CH, Schmael F, Pantev C. Attention improves population-level frequency tuning in human auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27(39):10383–10390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O’Connell MN, Barczak A, Schroeder CE, Lakatos P. Layer specific sharpening of frequency tuning by selective attention in primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34(49):16496–16508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lakatos P, Musacchia G, O’Connel MN, Falchier AY, Javitt DC, Schroeder CE. The spectrotemporal filter mechanism of auditory selective attention. Neuron. 2013;77(4):750–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xiao Y, Kellar KJ. The comparative pharmacology and up-regulation of rat neuronal nicotinic receptor subtype binding sites stably expressed in transfected mammalian cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(1):98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Whiteaker P, Wilking JA, Brown RW, et al. Pharmacological and immunochemical characterization of alpha2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in mouse brain. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30(6):795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wada K, Ballivet M, Boulter J, et al. Functional expression of a new pharmacological subtype of brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Science. 1988;240(4850):330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Han ZY, Le Novère N, Zoli M, Hill JA Jr, Champtiaux N, Changeux JP. Localization of nAChR subunit mRNAs in the brain of Macaca mulatta. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(10):3664–3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gotti C, Moretti M, Bohr I, et al. Selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit deficits identified in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies by immunoprecipitation. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23(2):481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nakauchi S, Brennan RJ, Boulter J, Sumikawa K. Nicotine gates long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region via the activation of alpha2* nicotinic ACh receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(9):2666–2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jia Y, Yamazaki Y, Nakauchi S, Sumikawa K. Alpha2 nicotine receptors function as a molecular switch to continuously excite a subset of interneurons in rat hippocampal circuits. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(8):1588–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kleeman E, Nakauchi S, Su H, Dang R, Wood MA, Sumikawa K. Impaired function of α2-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on oriens-lacunosum moleculare cells causes hippocampus-dependent memory impairments. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;136:13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lotfipour S, Mojica C, Nakauchi S, et al. α2* Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors influence hippocampus-dependent learning and memory in adolescent mice. Learn Mem. 2017;24(6):231–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Leão RN, Mikulovic S, Leão KE, et al. OLM interneurons differentially modulate CA3 and entorhinal inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(11):1524–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]