Abstract

Purpose

Children with advanced cancer are often not referred to palliative or hospice care before they die or are only referred close to the child’s death. The goals of the current project were to learn about pediatric oncology team members’ perspectives on palliative care, to collaborate with team members to modify and tailor three separate interdisciplinary team-based interventions regarding initiating palliative care, and to assess the feasibility of this collaborative approach.

Methods

We used a modified version of Experience Based Codesign (EBCD) involving members of the pediatric palliative care team and three inter-disciplinary pediatric oncology teams (Bone Marrow Transplant, Neuro-Oncology, and Solid Tumor) to review and tailor materials for three team-based interventions. 11 pediatric oncology team members participated in four codesign sessions to discuss their experiences with initiating palliative care and to review the proposed intervention including: patient case studies, techniques for managing uncertainty and negative emotions, role ambiguity, system-level barriers, and team communication and collaboration.

Results

The codesign process showed that the participants were strong supporters of palliative care, members of different teams had preferences for different materials that would be appropriate for their teams, and that while participants reported frustration with timing of palliative care, they had difficulty suggesting how to change current practices.

Conclusions

The current project demonstrated the feasibility of collaborating with pediatric oncology clinicians to develop interventions about introducing palliative care. The procedures and results of this project will be posted online so that other institutions can use them as a model for developing similar interventions appropriate for their needs.

Keywords: Pediatric oncology, Pediatric palliative care, experience based codesign, interdisciplinary collaboration, team interventions, uncertainty, role ambiguity, communication

Many parents of children who die of cancer wish they had received palliative care.[1,2] Children with advanced cancer are often not referred to palliative or hospice care before they die[3] or are only referred close to the time of death.[4] Palliative care referrals may be delayed because clinicians are unfamiliar with palliative care, unsure of when referrals are appropriate, uncomfortable with the uncertainty inherent in children with serious illness[5], worried about upsetting families by mentioning palliative care[6,7], experiencing negative emotions when considering palliative care, or viewing palliative care referrals as professional failures.[8,9]

Pediatric cancer clinicians, importantly, do not work alone, but instead in interdisciplinary oncology teams that include physicians (MDs), nurse practitioners (NPs), social workers (SWs), nurses, psychologists, and trainees.[10] Team level barriers to initiating palliative care may include diverging opinions among team members, group norms in favor of curative treatments, lack of guidelines for initiating palliative care, ambiguity about which team members should begin the discussion, and hierarchical barriers.[11,12] While communication training helps individual clinicians discuss difficult topics with patients and family members[13,14], most existing interventions do not address potential team-level barriers.

This project consisted of two phases. In Phase 1, we collaborated with pediatric oncology teams to modify and tailor a proposed team-based intervention that would: a) increase pediatric oncology clinicians’ understanding regarding palliative care and the variation in timing for initial consultation, b) introduce techniques for handling clinical uncertainty and associated negative emotions, and c) practice techniques for team communication and collaboration. In the current paper, we present the codesign process we used to modify previously developed materials and develop three separate interdisciplinary team-based interventions regarding initiating palliative care in pediatric oncology. Phase 2, the actual implementation of the three interventions, will be reported elsewhere.

OVERVIEW OF CODESIGN PHILOSOPHY AND TECHNIQUE

We employed a modified version of Experience Based Codesign (EBCD), a method for obtaining information about the experiences of patients, family members, and staff to improve their experience.[15] EBCD has been applied in adult palliative care[16], oncology[17,18], neonatal intensive care (NICU)[19,20], and mental health settings.[21] We also incorporated theories of adult learning, which suggest that interventions for self-directed adults are more successful if these learners help plan the intervention, the topics have immediate relevance, the instruction is task oriented, and learners of different backgrounds are accommodated.[22,23]

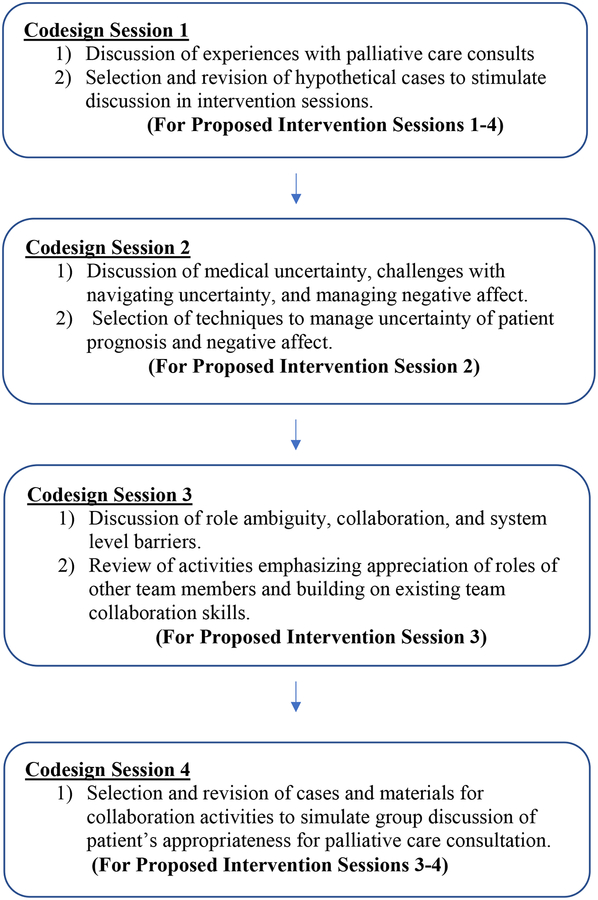

Pediatric palliative care clinicians (study team members JW and JC) collaborated with pediatric oncology clinicians who volunteered to help in the codesign process. The codesign of the intervention (Figure 1) served to: 1) develop three separate interventions tailored for each sub specialty team as opposed to providing one intervention for all three teams; 2) support clinicians interested in palliative care and help them think about barriers to palliative care; and 3) generate interventions that would have a greater impact than interventions developed by outside experts.

Figure 1:

Codesign Sessions and Proposed Intervention Sessions

RECRUITING CODESIGN PARTICIPANTS AND ARRANGING CODESIGN SESSIONS

For this developmental project, we invited members of the Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT), Neuro-Oncology, and Solid Tumor oncology teams at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) to participate. We emailed all 90 members (MDs, NP’s, and SWs) of these teams inviting them to participate in both Phase 1 (codesign) and Phase 2 (intervention) of the study. Additional individualized emails were sent to clinicians who were thought to be supportive of palliative care to encourage them to participate in Phase 1. A total of 11 team members (4 physicians, 3 nurse practitioners, and 4 social workers) provided informed consent and participated in the codesign phase of the project, providing nearly equal representation across the three teams by physicians, nurse practitioners, and social workers. Participation in all 4 sessions was not required to reduce the burden of the intervention. All participants engaged in at least one session, and some participants provided feedback on additional session materials by e-mail.

We arranged four codesign sessions with the participating oncology teams to: 1) discuss their experiences with initiating palliative care, 2) review the proposed intervention materials; 3) tailor the proposed intervention to each team; and 4) solicit feedback on how to maximize the intervention. Each of the four codesign sessions covered specific topics (see below) and were held twice for a total of 8 codesign sessions. We based the topics and order of sessions on a literature review and clinical experience regarding barriers to initiating palliative care at the individual level (lack of knowledge about palliative care, uncertainty about prognosis, negative emotions) and the team level (ambiguity of roles, lack of collaboration, system level barriers).

Although we developed separate interventions tailored for each team, each codesign session included participants from multiple teams and disciplines. We chose this approach so that codesigners could learn how other teams handled palliative care referrals and so the codesign sessions would include more than one or two people from each team in the discussion. Codesign sessions included an open-ended discussion about the participants’ experiences with the session topic, review of potential intervention materials, and participation in proposed activities. Study team members led each codesign session (JW, sessions 1–3; JC and DH, session 4), while two other team members observed and took descriptive observation notes on the conversation during the meetings, including verbatim statements on salient issues, the body language of participants, and modifications made by the session leader.[24]

Analytic Procedure

We used a modified grounded theory approach to analyze the meeting content and observation notes.[25] The core feature of our approach was iterative analysis, moving between data collection and analysis to develop an increasingly refined understanding of the needs of our participants in relation to the design of our intervention. Within two weeks after each session, study team members read the observation notes and discussed their impressions of how the session went, the strengths and weaknesses of the materials, and what changes were needed. When materials were modified after the first codesign session on a given topic, the revised materials were reviewed in the second codesign session. We then performed a focused analysis of our observation notes to identify key themes that emerged in each session. Two analysts read the notes of each session, identified recurrent themes, and met with the research team to discuss these observations. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. Verbatim statements reflective of common responses from participants were identified for inclusion in this manuscript.

CODESIGN SESSION 1

Discussion: Previous Experiences with Palliative Care Consultations

The session leader described the proposed intervention and asked open-ended questions about experiences with palliative care consults and whether participants had ever encountered situations where they felt patients were not referred to palliative care when appropriate and why these referrals did not happen. Participants were champions of palliative care who often sought ways to introduce palliative care to families earlier in the disease trajectory. They expressed frustration that palliative care was not offered earlier, but had few concrete ideas for changing this. Participants were concerned that those who most needed the intervention would not participate and the intervention would be “preaching to the choir.”

Participants reported considerable variation within and between teams in how palliative care was introduced, with the timing of the referral often dependent on the attending physician. Some team members had unwritten, informal rules for triggering palliative care consults (e.g. thinking to involve the palliative care team before initiating a second BMT). Providers reported struggling to find a balance between respecting a family’s wishes to continue curative treatment and preventing pain and suffering.

Review and Revision of Proposed Materials: Cases for Discussion

We prepared three patient cases to trigger discussion on specific topics in the intervention sessions based on the following criteria: 1) patient prognosis is poor with no curative options left, but the team does not know what the family wants; 2) patient prognosis is uncertain or patient has significant suffering but treatment options still exist, so team members might disagree about whether palliative care is appropriate; or 3) the team or family might question the chosen treatment plan, and there is likely conflict about whether to involve palliative care. Codesigners offered suggestions on how to revise the patient cases for each of their teams. We initially planned to use the same general cases to trigger the discussions for each subspecialty (e.g. use a neuro-oncology case for all three teams in Intervention Session 1). Participants suggested using team specific cases because they were not always familiar with terminology, prognosis, or treatment options in the other areas. We therefore developed separate cases for each team, which were edited based on in-person feedback and follow-up e-mails.

CODESIGN SESSION 2: SELECTION OF TECHNIQUES TO MANAGE UNCERTAINTY OF PATIENT PROGNOSIS

Discussion: Experiences with Uncertainty and Negative Emotions

We based the content of codesign session 2 on findings that health care professionals have trouble coping with uncertainty[26,27] and that low tolerance for uncertainty is associated with burnout.[28] Clinicians deciding whether to initiate pediatric palliative care often face uncertainty because children with life threatening illness have extremely variable prognoses and life expectancy.[29,30] Clinicians report that telling parents that their child might die (which many parents infer when palliative care is mentioned) is extremely stressful[5,31]. As a result, clinicians may be reluctant to mention palliative care until they are certain that the child is actively dying.

The session leader asked participants about negative emotions experienced when considering palliative care. One participant described the challenge of managing uncertainty, honesty, and empathy: “You can’t be truly empathic because you can’t really understand what it is like to be a parent or patient in that situation. You are trying to be honest and help the parent be comfortable with the decision they make ten years later. But you can’t just tell them what to do because so much is uncertain.” Another said, “I wish I could say ‘this is what you should do’ but it’s too paternalistic. It’s easier when there’s no uncertainty. It’s better when there’s a clear message from the beginning with less ambiguity.”

Review and Revision of Proposed Materials: Emotional Management Activities

The session leader introduced techniques for managing uncertainty and negative emotions based on mindfulness [32–34] and cognitive behavioral interventions.[35–37] The mindfulness activity was designed to help clinicians recognize uncertainty and negative emotions when relaying a poor prognosis without being overwhelmed by these emotions. The cognitive restructuring activities were designed to help clinicians identify and challenge cognitive errors or maladaptive beliefs associated with palliative care.

The codesign participants participated in activities of mindfulness, individual cognitive restructuring (thinking of cognitive errors they might personally make when considering palliative care), and group cognitive restructuring (saying aloud examples of cognitive errors team members might make and discussing possible challenges to these errors). Participants reported that while they personally found the mindfulness activity beneficial, some other team members would dislike this activity. Participants found the individual cognitive restructuring activity difficult: in one session they were able to suggest only one example of personal negative beliefs: “maybe I’m wrong and the patient still has a chance of getting better.” One participant reported that this activity reminded her of difficult experiences without helping her resolve any emotions. Participants had greater success with the group cognitive restructuring activity, suggesting many maladaptive beliefs related to palliative care referrals that other team members might experience (e.g. “I am giving up on the family if I refer them to palliative care”) and ways to challenge the maladaptive beliefs mentioned by others (e.g., “I’m offering this family another layer of support”). Participants also noted that some negative beliefs might be associated with certain roles. For example, physicians might be more likely to feel that they have failed if they cannot cure the patient.[38] Most participants said that the group cognitive restructuring activity would be most helpful for their team.

CODESIGN SESSION 3: ROLE AMBIGUITY, COLLABORATION, AND SYSTEM LEVEL BARRIERS

We based codesign session 3 on reports from interdisciplinary palliative care teams that roles are often blurred and effective communication and collaboration between team members is challenging.[39,40] In other contexts, medical teams often report system level or structural barriers that hamper efforts to meet patient needs.[20]

Discussion: Role Ambiguity, Collaboration, and System Level Barriers

Participants reported role and team dynamic challenges that sometimes delayed or prevented palliative care referrals. Social workers were not always included in initial family meetings, making it harder to effectively support families when the patient’s condition changed and palliative care was an appropriate option. Sometimes a social worker was the only clinician present at all family meetings, likely led by different attending physicians or specialists over time, and was the only clinician who knew what a family had been told previously. Clinicians were often reluctant to initiate a discussion of palliative care if they were unsure what information and options had already been offered to the family. Participants reported that sometimes other team members were surprised when a family was upset by a bad outcome (e.g. when a treatment with a low likelihood of working failed) and would ask, “Didn’t someone tell the family things might turn out this way?”. Social workers reported sometimes feeling disoriented after team members stated that the child’s prognosis was very poor, but later gave a more positive message to the child’s family, leaving social workers unsure about what they should say to the family about the child’s situation and whether the family or other team members would consider palliative care as an option.

The session leader asked whether system level barriers could delay palliative care referrals because team members were excluded from critical meetings and decisions. Participants reported that who was included in the family meeting sometimes depended on who was nearby at the right time, especially when events were happening quickly. Sometimes a decision was made not to overwhelm the family by bringing too many clinicians into the room.

One participant told a story that highlighted the challenge of deciding who to include in an initial family meeting about initiating palliative care. A fellow and two palliative care team members were coming to meet with the family. The mother commented, “Here they come, the women in the black cloaks,” because she knew having this many new people show up meant bad news for her child.

Participants had trouble suggesting ways to address these system level barriers. It was unclear whether they felt comfortable challenging team members reluctant to initiate palliative care. While participants rarely mentioned hierarchical barriers as a reason for not initiating palliative care, they suggested that timing of a consult often depended on the particular attending physician. Some participants showed fatalistic attitudes, expressing frustration about the current situation and skepticism that it would ever change.

Review and Revision of Proposed Materials: Role Ambiguity and Collaboration

The session leader introduced activities to augment awareness regarding the roles of other team members based (with permission) on materials from the University of California, San Francisco “TeamTalk 2015–16: Interprofessional Training in Palliative Care Communication”.[41] We asked participants to share aspects of their role (e.g. physician, nurse practitioner, social worker) and an experience when contributions from a team member in a different role were invaluable.

Some participants stated these activities were unnecessary since everyone on their team already knew and appreciated the work of other disciplines. But participants on larger teams thought some team members were not familiar with their role (e.g. some physicians saw the social work role as facilitating meal vouchers/transportation rather than as engaging families to help them address challenges).

The participants also reviewed materials about capacities and skills associated with collaborating successfully, also based on “TeamTalk 2015–16” materials (Table 1 and 2). Some participants strongly preferred the “skills” materials and the concrete examples of collaborative language. Other participants preferred the “capacities” materials, specifically self-awareness.

Table 1: Collaboration Capacities.

Capacities for challenging conversations and interprofessional teamwork

(Modified from UCSF TeamTalk 2015–16: Interprofessional Training in Palliative Care Communication)[41]

| Capacity | Example Practices |

|---|---|

| Self awareness |

|

| Compassion |

|

| Response flexibility |

|

| Reflective practice |

|

Table 2: Collaboration Skills.

(Modified from UCSF TeamTalk 2015–16: Interprofessional Training in Palliative Care Communication)[41]

| Skill | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Invite participation |

|

“what experiences have others had when talking with the family?” |

| Friendly questions | A respectful way to:

|

“Can you explain the thinking behind…?” “What would need to happen for [patient] to reach that goal?” “[Family member] asked me earlier…” |

| Seek Permission |

|

“Would it be OK if I ask a question?” “Can I ask question about something on a different topic?” |

| Kudos |

|

“[Nurse’s name] really worked hard to make sure that the family got their questions answered.” |

| Yes. And… |

|

“I agree that there are many treatment options to explore and I wonder if we might also focus on ensuring [patient’s] comfort while we’re doing so.” |

| Support to Disagree |

|

“I appreciate your position and can see why addressing these things is important to the patient.” |

| (re)Focus on the patient |

|

“It looks like we have different perspectives on this complex issue. What do you think [patient] needs right now?” “I know we’re both trying to do what’s right for this family.” |

CODESIGN SESSION 4: TEAM COLLABORATION

Review and Revision of Proposed Materials: Team Collaboration Activities

Participants reviewed collaboration activities proposed for the end of the 3rd Phase 2 intervention session and a longer activity that would comprise most of the 4th Phase 2 intervention session. In the first activity, participants are given a brief case, assigned a specific position to argue (e.g. recommending continuing with curative care, explaining pros and cons of curative care and palliative care, or recommending palliative care), and asked to reach consensus. The purpose of this activity is to help participants practice strategies they could use to advocate for a given position without having to personally commit to a position.

In the second longer activity proposed for the 4th Phase 2 session, all participants start with the same case, but team members are given different versions with key pieces of information about the case that they need to discuss in order to reach a decision. The versions are based on what an MD, NP, and Social Worker might each know about the case that the other team members do not. For example, the NP might know that the father is uncomfortable with opioid medications because of a history of opioid addiction, and the social worker may know that the family is under strain because the siblings are staying with their grandmother and the family has had little time together. This longer collaborative activity was designed to resemble situations that occur in caring for complex patients where different team members have varying pieces of critical information that may not be shared knowledge. Participants gave extensive feedback on how to make the cases, assigned positions, and “key pieces of information” credible.

DISCUSSION

This project sought to learn about pediatric oncology team members’ perspectives on palliative care, to collaborate in designing three separate interdisciplinary team-based interventions, and to assess the feasibility of this collaborative approach. Codesigning interventions with participants can identify and overcome subtle and entrenched barriers to changing practice in medical settings where frustrated clinicians are aware that delivered care is falling short of guidelines but are not sure how to improve the situation.[20,15,17] Some end-of-life care researchers have found that “bottom-up” interventions where team members collaborate to find a solution are more effective than “top down” interventions where new policies are issued.[42] In this project, codesign: 1) allowed codesigners to learn from each other about their perspectives on palliative care and barriers they have encountered; 2) tailored the intervention materials to be appropriate for each subspecialty team, and; 3) increased buy-in from codesign participants.

Overall this codesign process underscored the importance, when designing a team-based pediatric palliative care intervention, of asking members of each team about their experiences initiating palliative care, getting their feedback on specific materials, and tailoring intervention materials accordingly based on the experiences of team members. For example, participants had strong preferences for case scenarios specific to their field, while materials and activities that some team members thought would be helpful (e.g. mindfulness, role appreciation) were deemed unnecessary or unlikely to succeed by other team members. The codesign sessions revealed that while participants supported introducing palliative care earlier, they had difficulty articulating exactly what needed to change. Participants expressed a sense of fatalism: they were either in favor of or against earlier palliative care, with little confidence that other team members’ attitudes could be changed. Collectively, these findings suggest that future research and interventions should not focus just on changing individual clinicians’ palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Future efforts must also aim to understand and change how team members talk to each other about palliative care, and how team members can work together to introduce the idea of palliative care to patients and families.

Four limitations warrant discussion. Our findings, based on participants from three pediatric oncology specialty teams at one pediatric hospital, may not be generalizable to other oncology teams and other institutions. Due to limitations of study resources and scheduling constraints, hematologic malignancy clinicians did not participate in the study. Nurses and fellows were not included in the codesign sessions, and participation across sessions was higher among social workers and nurse practitioners than physicians, so the preferences of physicians, nurses, and fellows may not be accurately represented. We included previously identified champions of palliative care who self-selected to participate in the codesign process. This approach limits the conclusions we can draw about pediatric oncologists who are less supportive of palliative care.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current project demonstrated the feasibility of collaborating with pediatric oncology clinicians supportive of palliative care to explore their experiences with initiating palliative care and to modify and tailor an intervention for introducing palliative care for pediatric oncology patients to meet the unique needs of each oncology team. The outlines of the codesign sessions, handouts, and activity descriptions will be posted online on a CHOP-maintained website so that other institutions can use them as a model to develop interventions tailored to teams in their own institution. The materials posted will be presented as a methodology for codesigning palliative care referral interventions that are appropriate for a particular institution, rather than as an off-the-shelf intervention that can be implemented at any institution. Pediatric palliative care providers at other institutions could use the posted materials as a starting point for conducting their own codesign sessions with clinicians at their institution to develop an intervention meeting the needs of clinical teams interested in improving their palliative care referral process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the National Cancer Institute Grant R21CA198049–02. We thank all pediatric oncology team members who participated in this study. We thank Pamela G. Nathanson, MBE and Theodore E. Schall, MBE MSW for their comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Funding for this project was provided by the National Cancer Institute Grant R21CA198049–02. The National Cancer Institute had no role in the drafting, editing, review, or approval of this manuscript. The authors have no financial relationship with the National Cancer Institute other than the research grant. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report. The authors have full control of all primary data and will provide this data for review by Supportive Care in Cancer upon request.

References

- 1.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H (2002) Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediat Adol Med 156 (1):14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies B, Connaughty S (2002) Pediatric end of life care: Lessons learned from parents. Journal of Nursing Administration 32 (1):5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Chen LH, Cannavale K, Sattayapiwat O, Cooper RM, Chao CT (2015) End-of-Life Care Intensity Among Adolescent and Young Adult Patients With Cancer in Kaiser Permanente Southern California. JAMA Oncology. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhukovsky D, Herzog C, Kaur G, Palmer JL, Bruera E (2009) The impact of palliative care consultation on symptom assessment, communication needs, and palliative interventions in pediatric patients with cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12 (4):343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durall A, Zurakowski D, Wolfe J (2012) Barriers to Conducting Advance Care Discussions for Children With Life-Threatening Conditions. Pediatrics. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston DL, Vadeboncoeur C (2012) Palliative care consultation in pediatric oncology. Support Care Cancer 20 (4):799–803. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1152-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, Rodin G, Le LW, Sung L, Zimmermann C (2014) Referral practices of pediatric oncologists to specialized palliative care. Support Care Cancer 22 (9):2315–2322. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCabe ME, Hunt EA, Serwint JR (2008) Pediatric residents’ clinical and educational experiences with end-of-life care. Pediatrics 121 (4):e731–737. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson LA, Knapp C, Madden V, Shenkman E (2009) Pediatricians’ perceptions of and preferred timing for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics 123 (5):e777–782. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menard C, Merckaert I, Razavi D, Libert Y (2012) Decision-making in oncology: a selected literature review and some recommendations for the future. Curr Opin Oncol 24 (4):381–390. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328354b2f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle DK, Kochinda C (2004) Enhancing collaborative communication of nurse and physician leadership in two intensive care units. Journal of Nursing Administration 34 (2):60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC (2006) Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27 (7):941–966 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown CE, Back AL, Ford DW, Kross EK, Downey L, Shannon SE, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA (2016) Self-Assessment Scores Improve After Simulation-Based Palliative Care Communication Skill Workshops. Am J Hosp Palliat Care: 10.1177/1049909116681972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold RM, Back AL, Barnato AE, Prendergast TJ, Emlet LL, Karpov I, White PH, Nelson JE (2015) The Critical Care Communication project: improving fellows’ communication skills. J Crit Care 30 (2):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert G, Cornwell J, Locock L, Purushotham A, Sturmey G, Gager M (2015) Patients and staff as codesigners of healthcare services. Bmj 350:g7714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackwell RW, Lowton K, Robert G, Grudzen C, Grocott P (2017) Using Experience-based Co-design with older patients, their families and staff to improve palliative care experiences in the Emergency Department: A reflective critique on the process and outcomes. Int J Nurs Stud 68:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsianakas V, Robert G, Maben J, Richardson A, Dale C, Griffin M, Wiseman T (2012) Implementing patient-centred cancer care: using experience-based co-design to improve patient experience in breast and lung cancer services. Support Care Cancer 20 (11):2639–2647. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1470-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsianakas V, Robert G, Richardson A, Verity R, Oakley C, Murrells T, Flynn M, Ream E (2015) Enhancing the experience of carers in the chemotherapy outpatient setting: an exploratory randomised controlled trial to test impact, acceptability and feasibility of a complex intervention co-designed by carers and staff. Support Care Cancer 23 (10):3069–3080. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2677-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gustavsson S, Gremyr I, Kenne Sarenmalm E (2015) Designing quality of care - contributions from parents: Parents’ experiences of care processes in paediatric care and their contribution to improvements of the care process in collaboration with healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustavsson SM (2014) Improvements in neonatal care; using experience-based co-design. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 27 (5):427–438. doi: 10.1108/ijhcqa-02-2013-0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer VJ, Chondros P, Piper D, Callander R, Weavell W, Godbee K, Potiriadis M, Richard L, Densely K, Herrman H, Furler J, Pierce D, Schuster T, Iedema R, Gunn J (2015) The CORE study protocol: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial to test a co-design technique to optimise psychosocial recovery outcomes for people affected by mental illness in the community mental health setting. BMJ Open 5 (3):e006688. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knowles MS (1984) Adragogy in Action. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning PR, Clintworth WA, Sinopoli LM, Taylor JP, Krochalk PC, Gilman NJ, Denson TA, Stufflebeam DL, Knowles MS (1987) A method of self-directed learning in continuing medical education with implications for recertification. Ann Intern Med 107 (6):909–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL (1995) Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbin J, Strauss A (1990) Grounded theory method: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualiative Sociology 13:3–21 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith AK, White DB, Arnold RM (2013) Uncertainty: the other side of prognosis. The New England journal of medicine 368 (26):2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenker Y, White DB, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, Tiver GA, Arnold RM (2013) “It hurts to know…and it helps”: Exploring how surrogates in the ICU cope with prognostic information. Journal of Palliative Medicine 16 (3):243–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn G, Goldberg R, Compton S (2009) Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Annals of emergency medicine 54 (1):106–113.e106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, Friedrichsdorf SJ, Osenga K, Siden H, Friebert SE, Hays RM, Dussel V, Wolfe J (2011) Pediatric palliative care patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 127 (6):1094–1101. doi:peds.2010–3225 [pii] 10.1542/peds.2010-3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke J, Quin S (2007) Professional carers’ experiences of providing a pediatric palliative care service in Ireland. Qual Health Res 17 (9):1219–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foley KM, H G (2001) Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. National Academies Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabat-Zinn J (1982) An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 4 (1):33–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altschuler A, Rosenbaum E, Gordon P, Canales S, Avins AL (2012) Audio recordings of mindfulness-based stress reduction training to improve cancer patients’ mood and quality of life--a pilot feasibility study. Supportive Care in Cancer 20 (6):1291–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1216-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortney L, Luchterhand C, Zakletskaia L, Zgierska A, Rakel D (2013) Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: A pilot study. Annals of Family Medicine 11 (5):412–420. doi: 10.1370/afm.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT (2005) The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62 (9):953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glassman LH, Forman EM, Herbert JD, Bradley LE, Foster EE, Izzetoglu M, Ruocco AC (2016) The Effects of a Brief Acceptance-Based Behavioral Treatment Versus Traditional Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Public Speaking Anxiety: An Exploratory Trial Examining Differential Effects on Performance and Neurophysiology. Behav Modif. doi: 10.1177/0145445516629939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsson A, Hooper N, Osborne LA, Bennett P, McHugh L (2015) Using Brief Cognitive Restructuring and Cognitive Defusion Techniques to Cope With Negative Thoughts. Behav Modif. doi: 10.1177/0145445515621488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson VA, Mack J, Matsuyama R, Lakoma MD, Sullivan AM, Arnold RM, Weeks JC, Block SD (2008) A qualitative study of oncologists’ approaches to end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 11 (6):893–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klarare A, Hagelin CL, Furst CJ, Fossum B (2013) Team interactions in specialized palliative care teams: a qualitative study. Journal of Palliative Medicine 16 (9):1062–1069. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Connor M, Fisher C (2011) Exploring the dynamics of interdisciplinary palliative care teams in providing psychosocial care: “Everybody thinks that everybody can do it and they can’t”. Journal of Palliative Medicine 14 (2):191–196. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson W, Donesky D, Joseph D, Sumser B, Reid T (2016) Interprofessional Training in Palliative Care Communication Handout. University of California Regents [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amador S, Goodman C, Mathie E, Nicholson C (2016) Evaluation of an Organisational Intervention to Promote Integrated Working between Health Services and Care Homes in the Delivery of End-of-Life Care for People with Dementia: Understanding the Change Process Using a Social Identity Approach. Int J Integr Care 16 (2):14. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.