Abstract

Antibiotic allergy labels (AALs) are reported by approximately 20% of hospitalized patients, yet over 85% will be negative on formal allergy testing. Hospitalized patients with an AAL have inferior patient outcomes, increased colonization with multidrug‐resistant organisms and frequently receive inappropriate antimicrobials. Hospitalized populations have been well studied but, to date, the impact of AALs on patients with critical illness remains less well defined. We review the prevalence and impact of AALs on hospitalized patients, including those in in critical care.

Keywords: penicillin allergy, antimicrobial allergy, antimicrobial stewardship, acute care, skin testing

Introduction

Antibiotic allergy labels (AALs) are patient‐reported antibiotic allergies, that may represent an unpredictable immune mediated adverse drug reaction (ADR; e.g. anaphylaxis) or predictable nonimmune mediated (pharmacological) ADR (e.g. gastrointestinal upset). AALs are frequently reported in hospitalized patients 1, 2. Irrespective of whether these labels correctly apply to a true immune mediated reaction or incorrectly to a predictable nonimmune reaction, an AAL has the potential to persist in the medical record 3. AALs lead to the prescription of antibiotics that diverge from guidelines with increased risk of antimicrobial resistance, mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients 4, 5, 6. AALs increase rates of Clostridium difficile infection, emergence of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium and multidrug resistant Gram negatives – organisms of particular importance and pathogenicity for the critically ill subgroup of hospitalized patients 7, 8, 9, 10. It has been reported that upwards of 10–20% of hospitalized patients have an AAL, most commonly to a penicillin or β‐lactam, highlighting the enormous burden these AALs present 1, 6, 11, 12, 13.

A focus of the global effort to reduce antimicrobial resistance include the optimization of antimicrobial prescribing through stewardship programmes. Whilst novel antibiotic allergy testing (AAT) programmes have been successfully employed in hospital antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) practices, with subsequent reductions in restricted antibiotic usage noted, the impact of AALs in hospitalized patients, especially in critical care and the intensive care unit (ICU), is unknown 14, 15. We sought to understand the current burden and impact of AALs on the hospitalized and critically ill patient.

Methods

We performed a narrative review, examining literature via the Medline (Ovid) platform (September 2017 and February 2018), utilizing search terms: antibiotic allergy label, antibiotic allergy, antimicrobial allergy, penicillin allergy, β‐lactam allergy, antibiotic hypersensitivity, acute care, critical care, ICU, intensive care, acute medical, high dependency, antimicrobial stewardship, hypersensitivity delayed, hypersensitivity immediate, anti‐infective agents, antibacterial agents, antimicrobial resistance and bacterial resistance. We found 702 articles after limitation to the English language and articles published after 1990. In total, 150 articles were read in full after studies were excluded (case reports, case discussions, exclusively paediatric population or allergy studies that did not focus on the inpatient impacts of AALs). The bibliographies of identified publications were also checked for relevant studies.

Antibiotic allergy: mechanisms and definitions

An AAL can reflect an immunological or non‐immunological ADR and can be categorized into Type A or B according to their aetiology 16. Type A ADRs are predictable, dose‐dependent, pharmacological (non‐immune) effects of a drug, such as nausea and diarrhoea, and account for between 16–80% of AALs 1, 6, 11, 17, 18. Type B ADRs (or true antibiotic allergies) are unpredictable, non‐dose‐dependent and are immunologically mediated. Type B ADRs are subdivided into four categories (I–IV) depending on their immunological mechanism (Table 1) 19. There have been proposed revisions to these classical definitions, as some Type A reactions have been found to be dependent both on dose and genetic factors and the Type B reactions demonstrating predictable dose‐dependency, with some suggesting that a more simplified classification might refer to those reactions that are either on target (Type A) or off target (Type B) 20.

Table 1.

Immunological differentiation of Type B adverse drug reaction (ADRs)

| Type B ADR | Timing | Immunological Involvement | Antibiotic Examples | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | 30–60 min (immediate) or 6–48 h (accelerated) | IgE and mast cell | Beta‐lactams, sulfa antimicrobials, macrolides, fluoroquinolones | Pruritis, urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, anaphylaxis |

| Class II | 5–72 h (accelerated or delayed) | IgG or IgM, cytotoxic cells (phagocytes, natural killer cells) | Beta‐lactams, sulfa antimicrobials, rifampicin, dapsone, vancomycin | Haemolytic anaemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia |

| Class III | 3–72 h (accelerated or delayed) | IgG, antigen–antibody complex | Beta‐lactams (especially amoxicillin and cefaclor), sulfa antimicrobials, minocycline 57 | Serum sickness, acute interstitial nephritis, hypersensitivity vasculitis, |

| Class IV | 24–72 h (delayed) |

T‐cell mediated IVa (macrophage) IVb (eosinophil) IVc (T Cell) IVd (neutrophil) |

Beta‐lactams, sulfa antimicrobials, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, macrolides, dapsone, vancomycin, anti‐tuberculosis drugs | Severe cutaneous adverse reactions, erythema multiforme, morbilliform eruptions, SJS, TENS, DRESS |

Adapted from Trubiano et al. (with permission) 25, 58, Gell and Coombs 16, Pichler 19. Comparative table of the different type B adverse drug reactions and their immunological components, clinical presentations and time frames. SJS, Stevens–Johnsons syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrosis; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

The impact of AALs on hospitalized patients

North American and Australian studies have estimated that somewhere between 15 and 25% of all hospitalized patients have an AAL, with even higher rates reported in the immunocompromised 21, 22. It has been estimated that 30–40% of hospitalized patients with an AAL do not receive first‐line (preferred) antibiotics 12. Further, that the presence of a penicillin allergy also significantly delays time to first antibiotic dose (236.1 vs. 186.6 min; P = 0.03) 23. MacFadden et al. demonstrated that β‐lactam allergies in hospitalized patients were associated with a number of inferior patient outcomes (increased readmission rate, C. difficile infection, drug reaction or acute kidney injury) when patients were unable to receive therapy with a first‐line β‐lactam 24. Multiple reports have found that AALs are associated with a prescriber divergence from antibiotic guidelines, lower use of β‐lactams, greater use of broad spectrum antibiotics, prolonged use of intravenous compared to oral antibiotics, inferior patient outcomes and greater risk of antimicrobial resistance emergence (Table 2) 1, 4, 5, 7, 11, 13, 18, 25, 26. A review by Wu et al. found that seven of eight studies of hospitalised patients had various negative clinical, prescription and antibiotic utilization outcomes associated with AALs 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of studies looking at the impact of antibiotic allergy labels (AALs) on patient outcomes

| Study (Year) | Study Setting | Study design | Included ICU patients (Y/N) | Sample Size (n = patients) | AAL Prevalence (%) | Increased duration of ABx | Increased number of ABx | Reduced β‐lactam use | Increased restricted ABx use | Increased vancomycin use | Increased Quinolones use | Increased non‐oral ABx administration | Increased length of stay | Increased Mortality | Increased readmissions | Increased ICU admission | Increased Cost | Reduced ABx appropriateness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. (2000) 32 | Tertiary hospital (USA) | Retrospective single‐centre | Yes | 1893 | 25 | a | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| Charneski et al. (2011) 6 | Medical wards (USA) | Retrospective single‐centre, cohort | Yes | 11 872 | 11.2 | a | ✓ | a | a | a | a | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | a | a |

| Picard et al. (2013) 46 | ICU, CCU, medical wards (CAN) | Retrospective single‐centre, cross‐sectional | Yes | 1738 | 9.9 | a | a | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | a | a | a | a | a | ✓ | a |

| Macy et al. (2014) 7 | Californian hospitals (USA) | Retrospective multicentre, matched cohort | Yes | 51 582 | 11.2 | a | ✓ | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | a | ✓ | ✗ | a | a | ✓ | a |

| Trubiano et al. (2015) 18 | Tertiary hospital (AUS) | Retrospective single‐centre point prevalence | Yes | 509 | 25 | ✓ | a | ✓ | ✗ | a | a | ✓ | a | a | a | a | a | ✗ |

| Trubiano et al. (2016) 11 | Medical wards (AUS) | Retrospective multicentre, cross‐sectional | No | 453 | 24 | a | a | ✓ | ✓ | a | ✓ | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| Trubiano et al. (2015) 17 | Oncology wards (AUS) | Retrospective single‐centre | No | 198 | 23 | ✓ | ✓ | a | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | a | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | a | a | ✓ |

| Trubiano et al. (2016) 1 | Tertiary hospital (AUS) | Retrospective multicentre point prevalence | Yes5 | 21 031 | 18 | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | a | a | a | a | a | ✓ |

| Knezevic et al. (2016) 59 | Tertiary hospital (AUS) | Retrospective single‐centre, cross‐sectional | No | 687 | 18 | a | a | ✓ | a | a | a | a | ✗ | a | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | a |

| Lutomski et al. (2008) 60 | Tertiary hospital (USA) | Retrospective single‐centre | No | 300 | NA | a | a | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| Van Dijk et al. (2016) 61 | Tertiary hospital (NET) | Prospective single‐centre, matched cohort | No | 17 959 | 5.6b | a | ✓ | a | ✓ | a | ✓ | a | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | a | a | a |

| Conway et al. (2017) 23 | Veterans hospital ED (USA) | Retrospective single centre, study & interview | Yesd | 403c | 14.1 | ✗b | ✗ | a | ✓ | a | ✓ | a | ✗ | a | ✗ | a | a | a |

| Huang et al. (2018) 22 | Oncology wards (USA) | Retrospective cohort | No | 4671 | 35.1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | a | a | a | a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | a |

| Torda et al. (2018) 62 | Tertiary hospital (AUS) | Prospective single‐centre, cross‐sectional | No | 3855 | 14.4 | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

Direct comparison of observational articles providing insight of AAL impact on patient outcomes between various studied hospitalized and non‐hospitalized populations. Outcomes include effect on length of stay, mortality, readmission rate, type of antibiotic use and compliance to guidelines. No studies directly looked at AAL prevalence or impacts on ICU however Trubiano et al. 1 found an AAL prevalence of 24% for acute care specifically. Note that Huang et al. 22 found 35.1% of oncology patients had allergy to a non‐monobactam β‐lactam but classified patients with β‐lactam plus other antibiotic allergies as unexposed for analysis of outcomes. AUS, Australia; CAN, Canada; NET, The Netherlands; ICU, intensive care unit; ABx, antibiotic. ✓ Study looked for this finding and found a statistically significant result (P < 0.05). ✗ Study looked for this finding and did not find a statistically significant result (P > 0.05)

Study did not look for this finding

Study found increased time to first antibiotic administration

Study population included only those who presented with an infection requiring antibiotics

The ICU population was included and analysed separately

The burden of AALs on the critically ill

Recent work by Trubiano et al. identified that 24% of patients in acute care units, including ICU, had an AAL 1, while more specifically, up to 8–12% of patients in the emergency department and 8% in the ICU have a penicillin AAL 1, 12, 27. The reason for this high prevalence of AALs is probably multifactorial and includes those accumulated in childhood during a concurrent viral illness (e.g. viral exanthems or urticaria) 28, mislabelling of predictable antibiotic side effects as allergies (e.g. nausea, diarrhoea) and following high‐antibiotic usage in the acute care setting 3, 23, 29. Further compounding confusion surrounding AALs is that allergies and ADRs are often recorded within the same area of a medical record chart without allowance for differentiation of reaction types 30 and up to 36% of electronic records lacking an adequate description of the AAL 1, 6, 31, 32. These challenges are of particular importance in critically ill hospitalized patients where treatment is often time critical and clinicians may not have the opportunity to take a detailed history from the critically unwell patient or review a patient file to clarify the history of the ADR. This has been reflected in a 50‐min time‐delay in antibiotic administration seen in those reporting a penicillin allergy 23.

A study in hospitalized oncology patients, often critically ill, found that there was an increase in total antibiotic usage per admission, increased restricted antibiotic use, longer antibiotic duration, higher readmission rates and poorer concordance with antibiotic guidelines 17. Charneski et al. studied over 11 000 hospitalized patients and found that AALs were associated with increased length of stay (additional 1.2 days), higher mortality (adjusted odds ratio 1.6) and increased rate of ICU admission (adjusted odds ratio 1.4; Table 2) 6. Penicillin AALs are also associated with an increased rate of surgical site infections, relevant to surgical ICUs 33. Most studies looking at the prevalence of AALs and their associated outcomes are retrospective (Table 2) and literature describing the impacts of AAL on hospital cohorts with a high proportion of critically ill, such as ICU patients, is limited 34.

From a health economic perspective, AALs are associated with increased treatment cost – up to 63% – probably due to receipt of restricted antimicrobials and extended hospital length of stay 7, 35, 36. Costs are also increased in ICU patients who acquire nosocomial infections during their inpatient stay 10. Chagoya et al. demonstrated that inpatient testing of penicillin allergy with skin testing in the ICU facilitated more appropriate antibiotic selection without an increase in hospitalization cost 37.

Pathways to AAL de‐labelling in hospitalized patients: choice of testing and safety

In‐vivo confirmation of allergy status

Skin prick testing (SPT), intradermal testing (IDT) and oral provocation (i.e. oral rechallenge) are the most widely accepted methods of establishing an allergy phenotype 38. Whilst frequently undertaken in the outpatient setting, there is increased interest in employing these methods for hospitalized patients 5, 14, 15, 39. A 2017 systematic review of inpatient and ICU populations by Sacco et al. found that inpatient allergy testing was safe, efficacious and associated with subsequent improved antibiotic utilisation 40. Sacco et al. found that the population‐weighted mean for a negative SPT was 95.1%, similar to the studies listed in Table 3 40. There is evidence that critically ill patients or those taking systemic glucocorticoids have the high rates of negative SPT/IDT or a negative histamine result, raising concern of false negative results and highlighting the need for further validation in ICU cohorts 41, 42, 43. Whilst SPT/IDT is being increasingly performed by non‐allergists, the role of the intensivist, high‐dependency clinician or generalist is ill defined 14, 31, 43. A summary of the use of β‐lactam allergy testing and utilization in a variety of hospitalized patients, including the critically ill, is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of studies comparing skin prick testing for penicillin adverse drug reactions

| Study (year) | Study setting | Sample Size (n = patients) | Staff Performing SPT/IDT | Included ICU / ED / acutely unwell patients | Negative SPT/IDT (%) | Indeterminant SPT/IDT (%) | Included OP | Negative rate after OP (%) | Systemic adverse reactions | Recommendation to use PCN | Analysis of antibiotic use after SPT/IDT | Patients who changed antibiotics | Increased narrow spectrum antibiotics | Decreased restricted antibiotics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris et al. (1999) 63 | Hospital‐wide & presurgical | 44 | Not provided | Unknown | 86.0 | 7.0 | No | NA | 0 | 86% | Yes | 95% | ✓b | ✓a |

| Arroliga et al. (2000) 12 | Intensive care unit | 24 | Allergy service | Yes ICU, d | 95.0 | 4.8 | No | NA | 0 | 48% | No | 48% | ✓b | ✓b |

| Arroliga et al. (2003) 26 | Intensive care unit | 96 | Allergist supervision | Yes ICU, d | 88.5 | 10.4 | No | NA | 0 | 12–81% f | Yes | 39% | ✓a | c |

| Nadarajah et al. (2005) 44 | Hospital‐wide | 101 | Not provided | Yese | 91.1 | 3.9 | No | NA | 0 | 49% | Yes | 49% | ✓b | ✓b |

| Macy (2006) 64 | Pregnant inpatients and allergy clinic outpatients | 47 | Not provided | Unknownd | 93.6 | 0.0 | No | NA | 6 | 89% | Yes | 89% | ✓b | c |

| De Real et al. (2007) 42 | Hospital‐wide | 596 | Allergy Service | Yes ICU, e | 88.4 | 3.4 | Yes | NA | 5 | 49% | Yes | 55% | ✓b | ✓b |

| Raja et al. (2009) 36 | Emergency department | 150 | ED physicians | Yes ED, d | 91.3 | 0.0 | No | NA | 0 | NA | No | c | c | c |

| Rimawi and Mazer (2014) 47 | Intensive care unit | 100 | Various staff | Yes ICU, e | 100.0 | 0.0 | Yes | 100 | NA | 100% | Yes | 100% | ✓b | ✓b |

| Heil et al. (2016) 43 | Inpatient allergy clinic | 90 | ID fellow | Yes ICU, e | 96.0 | 12.0 | Yes | NA | 0 | 80% | Yes | 84% | ✓b | ✓a |

| Marwood et al. (2017) 27 | Emergency department | 100 | ED physicians | Yes ED, g | 81.0 | NA | Yes | NA | 0 | 81% | Yes | c | ✓a | c |

The table compares articles that confirmed allergy status of patients with an antibiotic allergy label using penicillin SPT/IDT ± OP. Negative rates varied between 88.4–95% of patients tested, similar to recent reviews. Studies that occurred in acute care settings (ED or ICU) are bolded for ease of reading. Studies used different combinations of penicillin derivatives for SPT/IDT as noted here (where available): Arroliga, Rimawi and Heil used benzylpenicilloyl polylysine (BPP) and penicillin G ‐ Heil used amoxycillin as oral provocation. Macy used BPP, penicillin, amoxicillin, penilloate, and penicilloate. Raja used penicillin major and minor determinants. Bourke used BPP, minor determinant mix (MDM) (sodium benzylpenicillin, benzylpenicilloic acid, sodium benzylpenicilloate), benzylpenicillin, amoxicillin, cefazolin and ceftriaxone plus/minus other penicillins, cephalosporins, or carbapenems was performed if clinically indicated. Marwood used BPP, MDM and amoxycillin. Harris used BPP and MDM (sodium penicilloate, sodium penilloate, and sodium benzylpenicillin). SPT, skin prick testing; IDT, intradermal testing; OP, oral provocation; ED, emergency department; ID, infectious disease physician; PCN, penicillin; NA, not available. ✓ Study looked for this outcome;

study found a statistically significant result (P < 0.05);

No statistical analysis conducted however clinically relevant results were found;

Study did not look for this outcome;

Further patient demographics unknown;

study included possibly acutely unwell patients (e.g. endocarditis, sepsis, bacteraemia);

study found 12% reduction for prophylactic and 18% reduction for therapeutic indications for antibiotic use;

study excluded severely unwell patients and those taking corticosteroid medications

Pathways to AAL de‐labelling: impact on AAL burden and antibiotic prescribing

The studies listed in Table 3 show a negative SPT/IDT result in 88–95% of patients tested, suggesting that only 5–11% of patients have a positive immunological reaction to penicillin derivatives 5, 12, 26, 36, 42, 44. Therefore only 1–2% of hospitalized patients are truly antibiotic allergic compared with the 10–20% of patients that report an allergy during hospital admission.

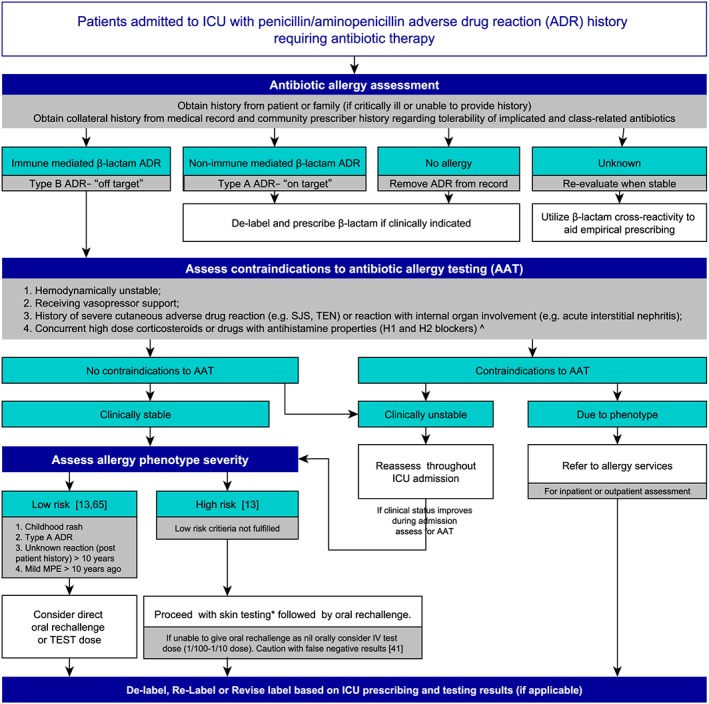

The SPT/IDT studies promoted an antibiotic change in approximately 70% of those tested hospitalized patients, with greatest numbers of antibiotic changes in orthopaedic or critically ill patients (Table 3) 4, 40, 42, 45. This is key, as Picard et al. 46 found that most patients with an indication for β‐lactam antibiotics were the patients in ICU and De Real et al. 42 found that 70% of their critically ill patients with an incorrect penicillin AAL had their antibiotic changed after SPT/IDT. SPT/IDT allows for the deployment of more appropriate antibiotics, reduced restricted antibiotic usage and lower risk of acquiring a drug resistant infection 12, 26, 36, 40, 44. Arroliga et al. 12, 26 and Rimawi and Mazer 47 demonstrated that SPT/IDT in the ICU allowed for increased guideline preferred antibiotic prescribing, crucial when considering the treatment of sepsis in the hospitalized and critically ill 48. Arroliga et al. also found that the rate of adverse reaction following SPT/IDT was not greater than the general population 26. None of the studies investigating penicillin allergies using SPT/IDT reported any serious adverse reactions with subsequent exposure to β‐lactams – with just five of 596 patients noting nonsevere dermatological type reactions (hives, nonspecific rashes, flushing, urticaria) 42. Whilst the potential benefit to critically ill patients following AAT is significant, larger studies looking at feasibility and impact on patient outcomes are required. A proposed algorithm for the assessment and management of patients with antibiotic allergies in the ICU, extrapolated from available research and available AAT literature is provided in Figure 1. This proposed algorithm requires future validation in the critical care setting.

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm for assessment and management of patients with antibiotic allergy label in ICU. A proposed algorithm to assist with the management of penicillin antibiotic allergy labels that are admitted to the intensive care unit who require antibiotics 13, 41, 65. ICU, intensive care unit; MPE, maculopapular exanthem; ADR, adverse drug reaction; IV, intravenous; SJS, Stevens–Johnston syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrosis; AAT, antibiotic allergy testing. ^Cautious of drugs with antihistamine properties, including antidepressants and cyclizine, *Refer to allergy testing guidelines for drug selection, doses and administration technique

Hospital antimicrobial stewardship and antibiotic allergies

Inappropriate antibiotic use has been identified as a strong mediator of antimicrobial resistance 49. Furthermore, a penicillin allergy is strongly associated with the acquisition of C. difficile infection, presumably related to the use of more broad‐spectrum antibiotics that disrupt the normal enteric flora 50. Infections with resistant organisms, particularly from multidrug resistant Gram negatives, are associated with excess morbidity and mortality 9. Recently, the assessment and testing of patients with AALs has been recognized as a novel antimicrobial stewardship tool to add to the fight against antimicrobial resistance 51, 52. In an Australian context, Trubiano and colleagues 15 have extensively studied the impact of AALs on antibiotic appropriateness and the role of AAT and multidisciplinary de‐labelling programmes in AMS (AAT‐AMS), to increase the use of appropriate and narrow spectrum antibiotic treatments. However, the incorporation of AAT‐AMS into hospitalized settings with a predominance of critically ill patients is yet to be formally evaluated 15.

Vitrat et al. recently reviewed the impact of AMS programmes on antibiotic utilization in the ICU and antimicrobial resistance and found that AMS was effective at increasing the appropriateness of antibiotic use and improving patient outcomes through improved guideline adherence, reduction in mortality, reduced length of stay, reduced drug resistant infections and reduced cost 53. To the authors knowledge, there have not been any published studies on the use of AAT by AMS services in the ICU setting but there is reason to hope that additional benefit may be gained from incorporating such AAT strategies into existing AMS programmes. The variety of AMS programmes already proven to be effective in the ICU population include antibiotic restriction, preauthorization, education and de‐escalation; however, an as yet unresearched avenue is the effect of de‐labelling inaccurate AALs 53, 54.

Conclusion

AALs are associated with increased hospital readmission rates, hospital costs, ICU admission and increased ICU length of stay. Furthermore, AALs negatively impact clinician antibiotic choices and are associated with poorer outcomes for hospitalized patients. The existing literature demonstrates the extent of the burden of AALs in hospitalized patients, particularly those critically unwell and in the ICU. Further work must be done to define the extent of AAL phenotypes in the setting of critical illness as part of a multifaceted approach to reducing antimicrobial resistance and optimizing patient outcomes.

Data demonstrating the utility of SPT/IDT to define AAL in the critically ill continue to mount. While numbers are small, they show that AAT may lead to significant changes in appropriate and preferred antibiotic usage. Concerns still exist regarding the potential for a false negative result in the critically ill and those receiving vasopressor support or immunosuppression, patients who are over‐represented in the ICU. While further work is necessary to determine the efficacy and safety of SPT/IDT in a range of illness settings in hospitalized, there is reason to hope that these techniques will evolve into a key component of antibiotic stewardship programmes in the ICU and lead to improved short‐ and long‐term patient outcomes in the future 55, 56.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

J.A.T. is supported by postgraduate scholarships from the National Health and Medical Research Council and The National Centre for Infections in Cancer, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

Moran, R. , Devchand, M. , Smibert, O. , and Trubiano, J. A. (2019) Antibiotic allergy labels in hospitalized and critically ill adults: A review of current impacts of inaccurate labelling. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 85: 492–500. 10.1111/bcp.13830.

References

- 1. Trubiano JA, Chen C, Cheng AC, Grayson ML, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, et al Antimicrobial allergy 'labels' drive inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing: lessons for stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu JH, Langford BJ, Schwartz KL, Zvonar R, Raybardhan S, Leung V, et al Potential negative effects of antimicrobial allergy labelling on patient care: a systematic review. Can J Hosp Pharm 2018; 71: 29–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trubiano JA, Adkinson NF, Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy is not necessarily forever. JAMA 2017; 318: 82–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Unger NR, Gauthier TP, Cheung LW. Penicillin skin testing: potential implications for antimicrobial stewardship. Pharmacotherapy 2013; 33: 856–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, Phillips E. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de‐labeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 365–34e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy 2011; 31: 742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin "allergy" in hospitalized patients: a cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 133: 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trubiano JA, Aung AK, Nguyen M, Fehily SR, Graudins L, Cleland H, et al A comparative analysis between antibiotic‐ and nonantibiotic‐associated delayed cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wernli D, Jørgensen PS, Harbarth S, Carroll SP, Laxminarayan R, Levrat N, et al Antimicrobial resistance: the complex challenge of measurement to inform policy and the public. PLoS Med 2017; 14: e1002378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nangino Gde O, Oliveira CD, Correia PC, Machado Nde M, Dias AT. Financial impact of nosocomial infections in the intensive care units of a charitable hospital in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de terapia intensiva 2012; 24: 357–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trubiano JA, Pai Mangalore R, Baey YW, le D, Graudins LV, Charles PGP, et al Old but not forgotten: antibiotic allergies in general medicine (the AGM study). Med J Aust 2016; 204: 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arroliga ME, Wagner W, Bobek MB, Hoffman‐Hogg L, Gordon SM, Arroliga AC. A pilot study of penicillin skin testing in patients with a history of penicillin allergy admitted to a medical ICU. Chest 2000; 118: 1106–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 115: 294–300e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017; 5: 686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trubiano JA, Thursky KA, Stewardson AJ, Urbancic K, Worth LJ, Jackson C, et al Impact of an integrated antibiotic allergy testing program on antimicrobial stewardship: a multicenter evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65: 166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gell PGH, Coombs RRA. In: Clinical aspects of immunology, eds Gell PGH, Coombs RRA. Philadelphia: Davis, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trubiano JA, Leung VK, Chu MY, Worth LJ, Slavin MA, Thursky KA. The impact of antimicrobial allergy labels on antimicrobial usage in cancer patients. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015; 4: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trubiano JA, Cairns KA, Evans JA, Ding A, Nguyen T, Dooley MJ, et al The prevalence and impact of antimicrobial allergies and adverse drug reactions at an Australian tertiary Centre. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pichler WJ. Drug hypersensivity reactions: Classification and relationship to T‐cell activation In: Drug Hypersensitivity, ed Pichler WJ. Basel (Switzerland): Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers, 2007; 168–169. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phillips EJ. Classifying ADRs ‐ does dose matter? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 10–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, Goss F, Topaz M, Slight SP, et al Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy 2016; 71: 1305–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang KG, Cluzet V, Hamilton K, Fadugba O. The impact of reported beta‐lactam allergy in hospitalized patients with hematologic malignancies requiring antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conway EL, Lin K, Sellick JA, Kurtzhalts K, Carbo J, Ott MC, et al Impact of penicillin allergy on time to first dose of antimicrobial therapy and clinical outcomes. Clin Ther 2017; 39: 2276–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. MacFadden DR, LaDelfa A, Leen J, Gold WL, Daneman N, Weber E, et al Impact of reported beta‐lactam allergy on inpatient outcomes: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Clinical Infect Dis 2016; 63: 904–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trubiano J, Phillips E. Antimicrobial stewardship's new weapon? A review of antibiotic allergy and pathways to 'de‐labeling. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013; 26: 526–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arroliga ME, Radojicic C, Gordon SM, Popovich MJ, Bashour CA, Melton AL, et al A prospective observational study of the effect of penicillin skin testing on antibiotic use in the intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003; 24: 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marwood J, Aguirrebarrena G, Kerr S, Welch SA, Rimmer J. De‐labelling self‐reported penicillin allergy within the emergency department through the use of skin tests and oral drug provocation testing. Emerg Med Australas 2017; 29: 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Caubet JC, Frossard C, Fellay B, Eigenmann PA. Skin tests and in vitro allergy tests have a poor diagnostic value for benign skin rashes due to beta‐lactams in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2015; 26: 80–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caubet JC, Kaiser L, Lemaitre B, Fellay B, Gervaix A, Eigenmann PA. The role of penicillin in benign skin rashes in childhood: a prospective study based on drug rechallenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127: 218–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moskow JM, Cook N, Champion‐Lippmann C, Amofah SA, Garcia AS. Identifying opportunities in EHR to improve the quality of antibiotic allergy data. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016; 23: e108–e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen JR. Evaluation of penicillin allergy in the hospitalized patient: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2017; 17: 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, Postelnick MJ, Greenberger PA, Peterson LR, et al The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 2819–2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66: 329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trubiano JA, Stone CA, Grayson ML, Urbancic K, Slavin MA, Thursky KA, et al The 3 Cs of antibiotic allergy‐classification, cross‐reactivity, and collaboration. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017; 5: 1532–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sade K, Holtzer I, Levo Y, Kivity S. The economic burden of antibiotic treatment of penicillin‐allergic patients in internal medicine wards of a general tertiary care hospital. Clin Exp Allergy 2003; 33: 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Raja AS, Lindsell CJ, Bernstein JA, Codispoti CD, Moellman JJ. The use of penicillin skin testing to assess the prevalence of penicillin allergy in an emergency department setting. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 54: 72–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chagoya JC, Heerey A, Diaz Guzman Zavala E, Gordon S, Arroliga M, Arroliga A. Economic analysis of the penicillin skin test for antibiotic selection in the intensive care unit. Chest 2004; 126 (Suppl. 4): 763S. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters , American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology , American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology , Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology . Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010; 105: 259–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernandez J, Torres MJ, Campos J, Arribas‐Poves F, Blanca M, DAP‐Diater Group . Prospective, multicenter clinical trial to validate new products for skin tests in the diagnosis of allergy to penicillin. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2013; 23: 398–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sacco KA, Bates A, Brigham TJ, Imam JS, Burton MC. Clinical outcomes following inpatient penicillin allergy testing: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy 2017; 72: 1288–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Geng B, Thakor A, Clayton E, Finkas L, Riedl MA. Factors associated with negative histamine control for penicillin allergy skin testing in the inpatient setting. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 115: 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. del Real GA, Rose ME, Ramirez‐Atamoros MT, Hammel J, Gordon SM, Arroliga AC, et al Penicillin skin testing in patients with a history of β‐lactam allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2007; 98: 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmalzle SA, Kleinberg M, Kewalramani A, Gilliam BL, et al Implementation of an infectious disease fellow‐managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3: ofw155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nadarajah K, Green GR, Naglak M. Clinical outcomes of penicillin skin testing. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 95: 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li JT, Markus PJ, Osmon DR, Estes L, Gosselin VA, Hanssen AD. Reduction of vancomycin use in orthopedic patients with a history of antibiotic allergy. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75: 902–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Picard M, Begin P, Bouchard H, Cloutier J, Lacombe‐Barrios J, Paradis J, et al Treatment of patients with a history of penicillin allergy in a large tertiary‐care academic hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1: 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rimawi RH, Mazer MA. Expanding the pool of healthcare providers to perform penicillin skin testing in the ICU. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40: 462–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43: 304–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kollef MH, Fraser VJ. Antibiotic resistance in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 298–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population based matched cohort study. BMJ 2018; 361: k2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ressner RA, Gada SM, Banks TA. Antimicrobial stewardship and the allergist: reclaiming our antibiotic armamentarium. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: 400–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: e51–e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vitrat V, Hautefeuille S, Janssen C, Bougon D, Sirodot M, Pagani L. Optimizing antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients. Infect Drug Resist 2014; 7: 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hou D, Wang Q, Jiang C, Tian C, Li H, Ji B. Evaluation of the short‐term effects of antimicrobial stewardship in the intensive care unit at a tertiary hospital in China. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e101447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar‐Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis‐3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Raith EP, Udy AA, Bailey M, McGloughlin S, MacIsaac C, Bellomo R, et al Prognostic accuracy of the SOFA score, SIRS criteria, and qSOFA score for in‐hospital mortality among adults with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. JAMA 2017; 317: 290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Legendre DP, Muzny CA, Marshall GD, Swiatlo E. Antibiotic hypersensitivity reactions and approaches to desensitization. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 1140–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kanji S, Chant C. Allergic and hypersensitivity reactions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2010; 38 (Suppl. 6): S162–S168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Knezevic B, Sprigg D, Seet J, Trevenen M, Trubiano J, Smith W, et al The revolving door: antibiotic allergy labelling in a tertiary care Centre. Intern Med J 2016; 46: 1276–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lutomski DM, LaFollette JA, Biaglow MA, Haglund LA. Antibiotic allergies in the medical record: effect on drug selection and assessment of validity. Pharmacotherapy 2008; 28: 1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. van Dijk SM, Gardarsdottir H, Wassenberg MW, Oosterheert JJ, de Groot MC, Rockmann H. The high impact of penicillin allergy registration in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 926–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Torda A, Chan V. Antibiotic allergy labels – the impact of taking a clinical history. Int J Clin Pract 2018; 17: 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Harris AD, Sauberman L, Kabbash L, Greineder DK, Samore MH. Penicillin skin testing: a way to optimize antibiotic utilization. Am J Med 1999; 107: 166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Macy EM. Penicillin skin testing in pregnant women with a history of penicillin allergy and group B streptococcus colonization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 97: 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017; 5: 813–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]