Bacterial internalization is the first step in breaking through the host cell defense. Therefore, studying the mechanism of bacterial internalization improves the understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of bacteria. In this study, the internalization process on nonphagocytic cells by Edwardsiella piscicida was evaluated. Our results showed that E. piscicida can be internalized into nonphagocytic cells via macropinocytosis and caveolin-mediated endocytosis, and that cholesterol and dynamin are involved in this process. These results reveal a new method for inhibiting E. piscicida infection, providing a foundation for further studies of bacterial pathogenicity.

KEYWORDS: Edwardsiella piscicida, endocytosis, internalization, macropinocytosis, nonphagocytic cells

ABSTRACT

Edwardsiella piscicida is an important pathogen that infects a wide range of hosts from fish to human. Recent studies demonstrated that E. piscicida can invade and survive within multiple nonphagocytic cells, but the internalization mechanism remains poorly understood. Here, we used HeLa cells as a nonphagocytic cell model to investigate the endocytic strategy used by the pathogenic E. piscicida isolate EIB202. Using a combination of optical and electron microscopy, we observed obvious membrane ruffles and F-actin rearrangements in HeLa cells after EIB202 infection. We also revealed that EIB202 internalization significantly depended on the activity of Na+/H+ exchangers and multiple intracellular signaling events related to macropinocytosis, suggesting that E. piscicida utilizes the host macropinocytosis pathway to enter HeLa cells. Further, using inhibitory drugs and shRNAs to block specific endocytic pathways, we found that a caveolin-dependent but not clathrin-dependent pathway is involved in E. piscicida entry and that its entry requires dynamin and membrane cholesterol. Together, these data suggest that E. piscicida enters nonphagocytic cells via macropinocytosis and caveolin-dependent endocytosis involving cholesterol and dynamin, improving the understanding of how E. piscicida interacts with nonphagocytic cells.

IMPORTANCE Bacterial internalization is the first step in breaking through the host cell defense. Therefore, studying the mechanism of bacterial internalization improves the understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of bacteria. In this study, the internalization process on nonphagocytic cells by Edwardsiella piscicida was evaluated. Our results showed that E. piscicida can be internalized into nonphagocytic cells via macropinocytosis and caveolin-mediated endocytosis, and that cholesterol and dynamin are involved in this process. These results reveal a new method for inhibiting E. piscicida infection, providing a foundation for further studies of bacterial pathogenicity.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial cells in the intestinal layer form an efficient barrier to protect the sterile host tissue against the entry of microbes from the rich intestinal flora. To establish and maintain a successful infection, invasive pathogens have evolved sophisticated strategies to actively induce their own uptake into normal epithelial cells and then either establish a protected niche within which they survive and replicate or disseminate between cells via an actin-based motility process (1, 2). Among these processes, bacterial internalization is a key step and initiates the intracellular lifestyle of intracellular pathogens. Thus, determining the bacterial internalization mechanism is very important for understand the pathogenesis of invading bacteria.

Pathogenic bacteria have devised common strategies, as well as unique tactics, to invade into host cells by manipulating a variety of existing host cellular endocytic pathways (for example, phagocytosis, caveolin-mediated endocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and macropinocytosis) to then move within the vacuolar apparatus of the cell and finally reach the sites where replication occurs (3, 4). Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is one of the best-studied receptor-dependent pathways, which is characterized by the formation of clathrin-coated pits and budding into the cytoplasm to form clathrin-coated vesicles (5). Listeria monocytogenes was reported to use its surface protein InlB to hijack this mechanism to invade mammalian cells (6). Francisella tularensis was also reported to use cholesterol and clathrin-based endocytic mechanisms to invade hepatocytes (7). Caveolin-mediated endocytosis is another important pathway that mediates bacterial internalization; this process depends on small vesicles named caveolae, which are enriched in caveolin, cholesterol, and sphingolipid (8). This endocytosis pathway has been implicated in the entry of some pathogens, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (9). In addition, macropinocytosis is one of the most archaic eukaryotic endocytic pathways, which primarily mediates nonselective uptake of fluid and large particles (10). In recent years, an increasing number of pathogens, including Legionella pneumophila (11), Brucella spp. (12), Mycobacterium spp. (13), and Shigella spp. (14), have been found to invade host cells via macropinocytosis.

Edwardsiella piscicida is an important fish pathogen causing systemic infections in a wide variety of marine and freshwater fish and infecting other hosts, ranging from birds and reptiles to mammals. This bacterium even causes gastrointestinal infections, as well as extraintestinal infections such as myonecrosis, bacteremia, and septic arthritis (15). E. piscicida has been reported to infect humans and cause bacteremia and other medical conditions (16), and it causes enteric septicemia in different fish species and generates severe economic losses in aquaculture worldwide (17). Like many invasive pathogens, E. piscicida enters host cells as the initial step of infection. It is capable of invading and replicating in host phagocytes and nonphagocytes, which is crucial for its pathogenicity (18, 19). However, most studies have focused on phagocytes. It was demonstrated that E. piscicida invades macrophages as a niche for virulence priming and then induces macrophage death to escape for further dissemination (19). In addition, a very recent study revealed that E. piscicida enters macrophages via both clathrin- and caveolin-mediated endocytosis (20). Although E. piscicida is known to invade nonphagocytic cells, the detailed mechanism of its entry remains unclear. Here, we examine the internalization process of E. piscicida EIB202 in nonphagocytic cells and demonstrate that E. piscicida uses a hybrid endocytic strategy to invade nonphagocytic cells, which has the hallmarks of macropinocytosis with caveolin-, cholesterol-, and dynamin-dependent features. These results reveal the basic mechanisms of E. piscicida internalization into nonphagocytic cells, improving the fundamental understanding of E. piscicida infection mechanisms.

RESULTS

Edwardsiella piscicida infection induces membrane ruffles and alters the actin cytoskeleton.

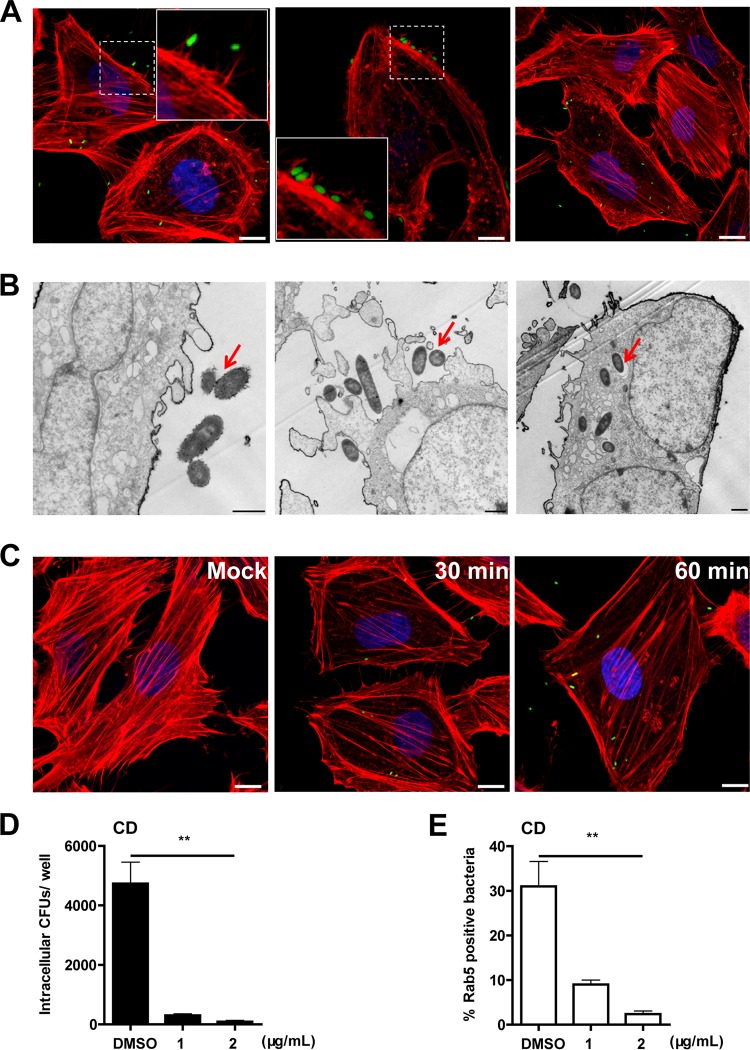

To identify the internalization mechanism of E. piscicida into nonphagocytic cells, we first characterized the entry and intracellular survival process of E. piscicida EIB202 within HeLa cells. As shown in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material, after rapid internalization into HeLa cells within 2 h, the bacterium replicated inside the cells over time, reaching a maximum propagation level at 8 h. Because the ratio of internalization for 2 h postinfection was only 0.056 CFU/cell and to further assay the internalization capability of E. piscicida in HeLa cells, we next examined whether it was possible to increase the ratio by changing the multiplicity of infection (MOI). We incubated the cells with E. piscicida at different MOIs and counted intracellular E. piscicida cells at 0.5, 1, and 2 h postinfection. As the incubation time increased, E. piscicida showed a significantly enhanced internalization level. Increasing the MOI slightly promoted E. piscicida internalization when the MOI was >300 (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Subsequently, we monitored the uptake process of E. piscicida by confocal microscopy. Ruffles were observed on the cell surface of infected cells (Fig. 1A). The invading E. piscicida contacted the cell membrane, was wrapped in the ruffles (Fig. 1A), and then invaded Rab5-positive early endosomes (Fig. S1C and D). Similarly, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis showed that the invading bacteria induced and contacted the ruffles protruding from the cell surface and then were internalized into cells via a membrane-closed vacuole (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Edwardsiella piscicida infection induces membrane ruffles and alters actin cytoskeleton. HeLa cells were infected with EIB202 (p-GFP-uv or wild-type) at an MOI of 300 for 1 h. (A) The infected cells were fixed for confocal microscopy. F-actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (red), while the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 µm. (B) After infection, the cells were harvested and fixed for TEM. The arrows indicate the bacteria. Scale bars, 1 μm. (C) HeLa cells were infected with EIB202 and, at the indicated times postinfection, the cells were fixed for confocal microscopy. F-actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (red), while the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 µm. (D) Pretreated cells with DMSO or CD were infected with EIB202, bacterial internalization was examined, and the results are shown as intracellular CFU per well. Graphs show the means ± the SD from triplicate cultures, and data are representative of at least three experiments (**, P < 0.01 [unpaired two-tailed Student t test]). (E) Rab5 colocalization was examined in HeLa cells pretreated with CD. After infection, the cells were fixed for confocal microscopy (data are not shown), and the ratio of Rab5-positive bacteria was quantified. The data are representative of the means ± the SD of 30 views from three individual experiments.

Considering that pathogens commonly regulate dynamic changes of the cytoskeleton to facilitate their entry (21), we next assessed the changes in actin microfilaments in HeLa cells during E. piscicida infection. Figure 1C shows the obvious actin rearrangements that occurred in HeLa cells at 30 and 60 min postinfection compared to in uninfected cells. To further investigate the importance of actin rearrangements in EIB202 internalization, we pretreated HeLa cells with cytochalasin D (CD), an inhibitor of actin microfilaments that binds to the positive end of F-actin, impairs further addition of G-actin, and thus prevents the growth of the microfilament (22). Internalization of bacteria was significantly inhibited to 10% in CD-treated cells compared to in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells (Fig. 1D). In addition, blocking actin rearrangements by CD significantly reduced the number of Rab5-associated bacteria, indicating that the process by which EIB202 invades Rab5-postive early endosomes also requires actin dynamics (Fig. 1E).

Taken together, these data strongly indicate that E. piscicida internalization is associated with plasma membrane activity during the first step of infection, which also requires depolymerization of the actin cytoskeleton.

Edwardsiella piscicida entry is dependent on the endocytic pathway macropinocytosis.

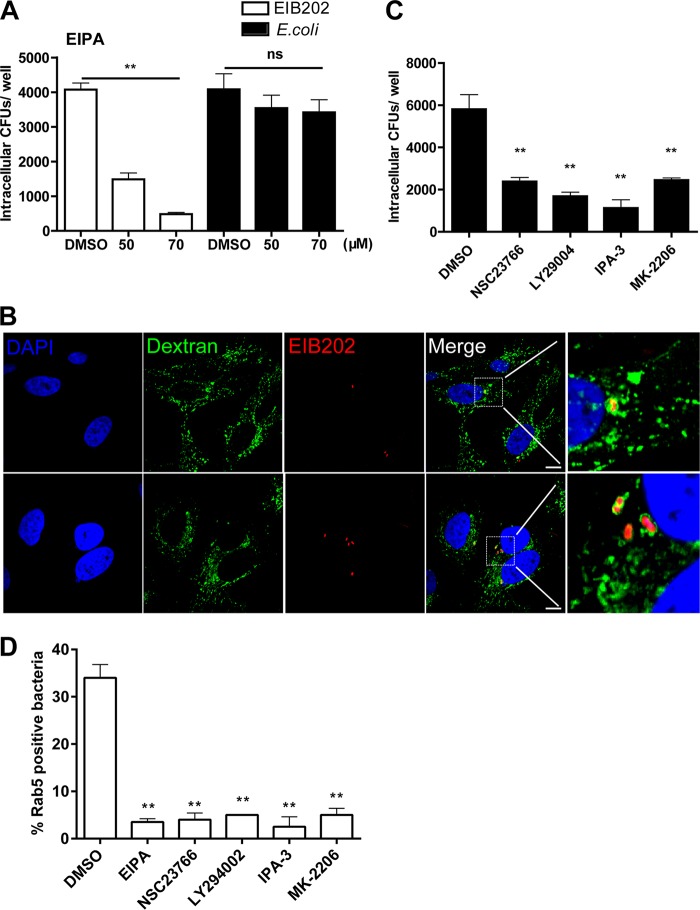

Because ruffle formation on the cellular surface is a specific feature of macropinocytosis and macropinocytosis is known to be an actin-dependent endocytic process that requires actin rearrangements to induce membrane ruffling formation (23), we predicted that the macropinocytosis-based endocytotic pathway is involved in the internalization of EIB202 into HeLa cells. Macropinocytosis depends on Na+/H+ exchangers (24), and 5-(N-ethyl-n-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA) has been shown to specifically inhibit Na+/H+ exchangers and therefore inhibit macropinocytosis without affecting other processes (25). To further assess the involvement of macropinocytosis in EIB202 internalization, the effect of EIPA was investigated. The results showed that the ratio of bacterial internalization was greatly reduced (approximately 85%) in the presence of 70 μM EIPA (Fig. 2A). In contrast, EIPA had no effect on infection by Escherichia coli, which enters HeLa cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (26). Moreover, to confirm that EIB202 entry occurs by macropinocytosis, during EIB202 infection, we investigated the colocalization of bacteria with dextran, a marker of macropinosomes (27). As indicated in Fig. 2B, multiple vesicles containing dextran were observed surrounding EIB202, while colocalization of EIB202 and dextran was also detected. Together, these results suggested that macropinocytosis is involved in EIB202 entry into HeLa cells.

FIG 2.

Edwardsiella piscicida entry is dependent on macropinocytosis-related signals and is associated with macropinosomes. (A) HeLa cells were pretreated with EIPA for 30 min, the cells were then infected with EIB202 or E. coli for 1 h in the presence of EIPA, and intracellular bacteria was examined at the end of infection. ns, not significant. (B) HeLa cells were incubated with FITC-dextran 30 min prior to infection. Infected cells were washed with PBS and fixed for confocal microscopy. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Macropinosomes were characterized by dextran (green). Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) HeLa cells were pretreated with inhibitors for 30 min prior to infection. Cells were then incubated with EIB202 for 1 h, and intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. Graphs show the means ± the SD from triplicate cultures, and data are representative of at least three experiments (**, P < 0.01 [unpaired two-tailed Student t test]). (D) Rab5 colocalization was detected in the presence of EIPA (70 μM), NSC23766 (300 μM), LY294002 (60 μM), IPA-3 (50 μM), or MK-2206 (15 μM). Infected cells were fixed for confocal microscopy (data are not shown), and the ratio of Rab5-positive bacteria was quantified. The data are representative of the means ± the SD of 30 views from three individual experiments.

In most situations, macropinocytosis is typically initiated by external stimulation, which activates signaling pathways to induce the formation of macropinosomes (10). Within these signaling pathways, Rho GTPases such as Rac1 are responsible for triggering membrane ruffles (28). Next, kinases such as p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1) are activated by Rac1 (29), and activated Pak1 regulates cytoskeleton dynamics and motility and is needed during all stages of macropinocytosis (30). Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) is another kinase involved in macropinocytosis and is essential for the closure of macropinocytic cups and macropinosome fusion (31). Further, Akt has been reported to be a major downstream effector of the PI3K pathway, and Akt phosphorylation has been considered to be involved in macropinosome formation (32). To investigate whether macropinocytosis-related signals are involved in the internalization of EIB202, the roles of NSC23766 (inhibitor of Rac1), LY294002 (inhibitor of PI3K), IPA-3 (inhibitor of Pak1), and MK-2206 (inhibitor of Akt) were assessed. The dose and cytotoxicity of inhibitors were detected (data not shown). The results showed that bacterial internalization was significantly decreased when infection was performed in the presence of these pharmacological inhibitors (Fig. 2C). Consistently, suppression of macropinocytosis-related signals reduced bacterial trafficking to Rab5-positive vesicles, indicating that macropinosome formation is important for EIB202 invasion into Rab5-positive early endosomes (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these results demonstrate the important role of macropinocytosis-related signals in EIB202 entry.

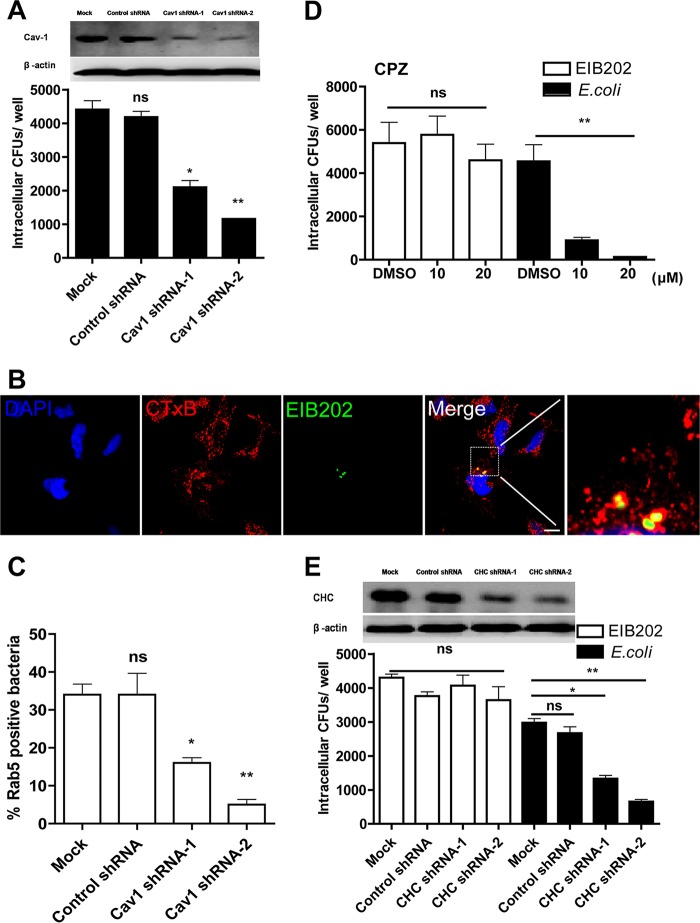

Edwardsiella piscicida entry is caveolin dependent but clathrin independent.

Because clathrin- and caveolin-mediated endocytic pathways are hijacked by E. piscicida to invade macrophage cells, we further examined whether these pathways are involved in the entry of nonphagocytic cells. First, the caveolin-mediated endocytic pathway was investigated by inhibiting caveolin-1 (Cav-1) expression, which was reported to play a crucial role in the formation and stability of caveolae (33). For this study, while Cav-1 expression in HeLa cells was inhibited by Cav-1 shRNA treatment, the ratio of EIB202 internalization was reduced to 30 to 50% compared to that in control shRNA-treated cells (Fig. 3A), indicating that interdicting caveolin-mediated endocytosis by Cav-1 shRNA significantly inhibited the internalization of EIB202. In addition, Alexa Fluor 647-cholera toxin subunit B (CTxB) was administered as a marker of Cav-1-positive structures to characterize caveolin-mediate endocytosis (34). The confocal images showed that during infection, multiple CTxB-labeled vesicles were present around the bacteria (Fig. 3B), demonstrating the involvement of the caveosome in internalization of EIB202 into HeLa cells. As expected, in cells treated with Cav-1 shRNA, bacterial recruitment of Rab5 was significantly inhibited (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Edwardsiella piscicida entry is caveolin dependent, but clathrin independent. (A) HeLa cells transfected with shRNA targeting caveolin-1 (Cav1) or control shRNA were infected with EIB202; after infection, intracellular bacteria was examined. (B) HeLa cells were pretreated with AF-CTxB for 30 min. Infected cells were fixed and dyed for confocal microscopy. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Rab5 colocalization was examined in HeLa cells transfected with Cav1 shRNA. (D and E) HeLa cells pretreated with chlorpromazine (CPZ) (D) or transfected with CHC shRNA (E) were infected with EIB202 or E. coli, and then intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. Graphs show the means ± the SD from triplicate cultures, and the data are representative of at least three experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant [unpaired two-tailed Student t test]).

To determine whether clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is involved in E. piscicida invasion, we first analyzed the levels of bacterial internalization in the presence of the chemical inhibitor chlorpromazine (CPZ), which inhibits the assembly of coated pits at the plasma membrane and is considered as a specific inhibitor of CME (35). CPZ treatment at 20 μM did not affect cell vitality (data not shown). In addition, internalization of E. coli, which was reported to internalize into HeLa cells via CME (26), was obviously reduced in the presence of 20 μM CPZ, while internalization of EIB202 in CPZ-treated cells showed no difference compared to DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 3D). To complement the drug inhibition experiments, clathrin expression in HeLa cells was downregulated by the specific clathrin heavy chain (CHC) shRNA, and the effect on expression of the respective knockdown was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 3E). Similar to the results of CPZ treatment, the uptake of E. coli was inhibited to a low extent in cells treated with CHC shRNA, while internalization of EIB202 was not inhibited (Fig. 3E). These results strongly suggest that EIB202 internalization into HeLa cells is clathrin independent.

Taken together, these results indicate that caveolin-mediated endocytosis but not clathrin-mediated endocytosis plays an important role in EIB202 internalization.

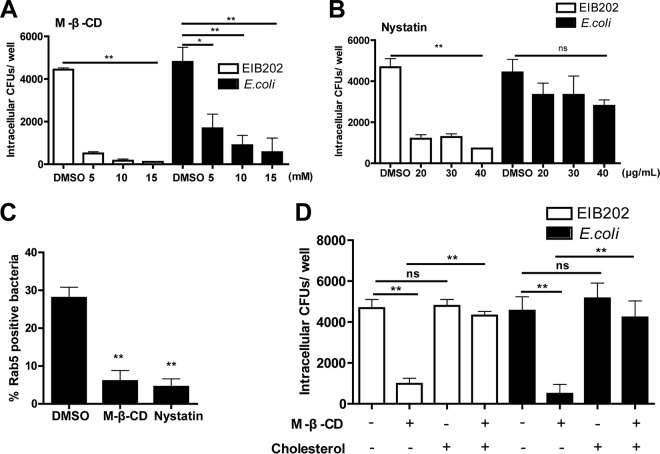

Cholesterol is necessary for E. piscicida entry.

Because the caveolin-mediated endocytic pathway depends on cholesterol, which is the main component of lipid rafts in the caveolae (36), and because we determined the requirement for caveolin-dependent endocytosis in EIB202 invasion, we next assessed the role of cholesterol in EIB202 internalization. In this study, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD; cholesterol-deleting compound) (37) at the indicated concentrations was used to treat HeLa cells. The results showed that internalization of EIB202 was dramatically inhibited in the presence of MβCD, with internalization by E. coli showing the same trend (Fig. 4A), suggesting that cholesterol is required during the internalization process of EIB202 on HeLa cells. Nystatin, another cholesterol-sequestering agent that selectively interrupts caveola/lipid raft-dependent endocytosis without affecting clathrin-mediated internalization (33), also markedly reduced bacterial internalization but showed no influence on E. coli (Fig. 4B). In addition, elimination of endogenous cholesterol inhibited bacterial recruitment of Rab5 (Fig. 4C). To confirm that the inhibitory effects on EIB202 entry were caused by cholesterol depletion, cell membrane cholesterol was replenished with a high concentration of exogenous cholesterol, and the recovery of EIB202 entry was analyzed. The results showed that the inhibitory effect was partially reversed by cholesterol replenishment, and the entry efficiency of cholesterol replenishment samples was restored to a mean of 88% compared to mock-treated cells (Fig. 4D). As a control, exogenous cholesterol also restored the internalization of E. coli after MβCD treatment (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results indicate that internalization of EIB202 into HeLa cells requires cholesterol.

FIG 4.

Cholesterol is necessary for E. piscicida entry. (A and B) Cells pretreated with MβCD (A) or nystatin (B) were infected with EIB202 or E. coli, and then intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. (C) Rab5 colocalization was detected in the presence of MβCD (10 mM) or nystatin (40 μg/ml). (D) MβCD (10 mM)-treated HeLa cells were incubated without or with exogenous cholesterol for 30 min, the cells were then infected, and intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. Graphs show the means ± the SD from triplicate cultures; data are representative of at least three experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant [unpaired two-tailed Student t test]).

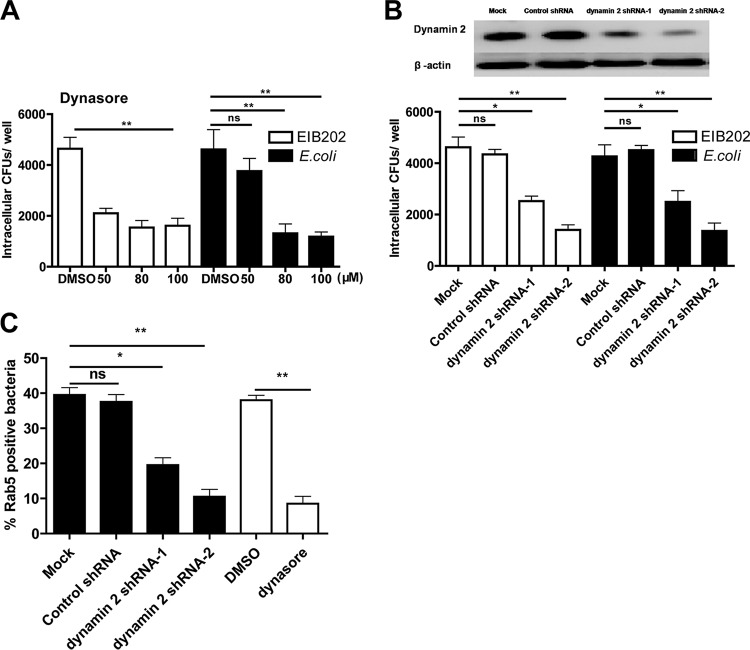

Dynamin is crucial for E. piscicida entry.

Dynamin is an essential GTPase that plays an important role in cellular membrane fission during vesicle formation and macropinocytosis (38) and was also found at the neck of caveolae (39). To verify the effect of dynamin on E. piscicida internalization, we pretreated HeLa cells with dynasore, a reversible inhibitor of dynamin (40), and then analyzed EIB202 invasion. The results showed that internalization of EIB202 was significantly inhibited by dynasore treatment (Fig. 5A), indicating that EIB202 uptake by HeLa cells requires dynamin. Moreover, EIB202 internalization was inhibited in cells treated with dynamin 2 shRNA compared to cells treated with control shRNA (Fig. 5B). As observed for EIB202, the absence of dynamin inhibited the internalization of E. coli (Fig. 5A and B). Simultaneously, bacterial recruitment of Rab5 required dynamin, as shown in Fig. 5C. Together, these results indicate that dynamin is necessary for EIB202 internalization into HeLa cells.

FIG 5.

Dynamin is crucial for E. piscicida entry. (A) Cells pretreated with dynasore were infected with EIB202 or E. coli, and then intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. (B) Cells transfected with dynamin 2 shRNA or control shRNA were incubated with EIB202 or E. coli, and intracellular bacteria was examined at the end of infection. Graphs show the means ± the SD from triplicate cultures; the data are representative of at least three experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant [unpaired two-tailed Student t test]). (C) Rab5 colocalization was detected after dynasore or dynamin 2 shRNA treatments. Infected cells were fixed for confocal (data are not shown), and the ratio of Rab5-positive bacteria was quantified. The data are representative of the means ± the SD from >30 cells per treatment and from three individual experiments.

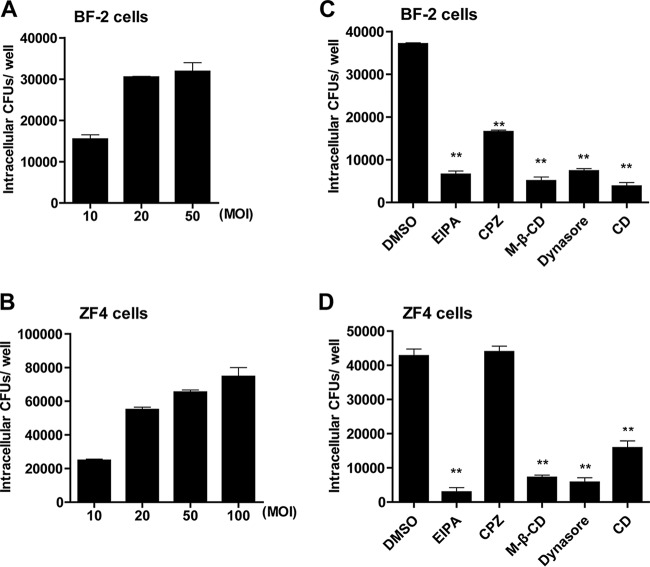

Edwardsiella piscicida enters different nonphagocytic cells via different endocytic pathways.

Edwardsiella piscicida is an important intracellular pathogen of fish and efficiently infects many fish nonphagocytic cells. Thus, the infection mechanisms of E. piscicida toward nonphagocytic cells of different fish were additionally examined. We explored the internalization mechanisms of E. piscicida using zebrafish fibroblasts (ZF4) and a bluegill fry cell line (BF-2). In agreement with previous reports, EIB202 was internalized into fish cells and showed a robust invasion capability toward BF-2 and ZF4 cells (Fig. 6A and B). These results indicate that E. piscicida enters HeLa cells via a macropinocytosis- and caveolin-dependent but clathrin-independent endocytosis mechanism involving cholesterol and dynamin; therefore, their roles for E. piscicida infection were similarly investigated in these cells. Pretreatment of these two fish cells with different inhibitors, including EIPA, MβCD, dynasore, and CD, significantly reduced E. piscicida invasion both in BF-2 and ZF4 cells, suggesting that E. piscicida also utilizes macropinocytosis to invade fish cells in a process requiring cholesterol and dynamin (Fig. 6C and D). Interestingly, E. piscicida internalization was inhibited by CPZ in BF-2 cells, in contrast to ZF4 and HeLa cells, suggesting that clathrin-mediated endocytosis is required for BF-2 cells (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these results revealed that E. piscicida enters different fish nonphagocytic cells via macropinocytosis and that entry involves cholesterol and dynamin.

FIG 6.

Edwardsiella piscicida enters different nonphagocytic cells via different endocytic pathways. (A and B) BF-2 cells (A) and ZF4 cells (B) were incubated with EIB202 at different MOIs for 1 h, and then intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. (C and D) BF-2 cells (C) and ZF4 cells (D) were pretreated with different inhibitors for 30 min prior to infection, after which intracellular bacteria were examined at the end of infection. Graphs show the means ± the SD from triplicate cultures; data are representative of at least three experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 [unpaired two-tailed Student t test]).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, a familiar theme of endocytic protein hijacking by microbial pathogens has developed. Although E. piscicida has been identified as an invasive intracellular pathogen (15) and previous studies have been carried out in HeLa cells (41, 42), its internalization process in nonphagocytic cells remains unclear. Most previous studies of E. piscicida invasion into nonphagocytic cells have focused on the invasive features and intracellular survival. One study demonstrated that E. piscicida can invade human epithelial cells (HEp-2) and repress NF-κB activation for intracellular growth (43, 44). Another study demonstrated that E. piscicida infects the zebrafish cell line ZF4 and inhibits apoptosis as a strategy for intracellular survival (45). Although these important studies demonstrated the ability of E. piscicida to replicate within nonphagocytic cell types, the internalization strategies utilized by this microbe during its invasion events required further investigation. In the present study, we explored the E. piscicida endocytic pathway using several nonphagocytic cells.

We utilized microscopy methods to track the internalization of E. piscicida into cells and observed fast attachment of the bacteria onto the cell surface at as early as 30 min. In addition, both confocal microscopy and TEM images showed that prominent membrane protrusions were induced around infecting bacteria, which is a specific characteristic of macropinocytosis. Based on these results, we further investigated whether macropinocytosis is involved in E. piscicida entry. Apart from characteristic membrane perturbations, macropinocytosis is distinguished from other entry pathways by actin-dependent structural changes in the plasma membrane, regulation by Na+/H+ exchangers, PI3K, Pak1, and Rho family GTPases, as well as ligand-induced upregulation of fluid phase uptake. Our data demonstrated that E. piscicida infection induced actin cytoskeleton rearrangements, and internalization of E. piscicida was significantly reduced by pretreatment with specific pharmacological inhibitors of Na+/H+ exchangers, PI3K, Pak1, and Rho family GTPase Rac1. In addition, E. piscicida was found to be colocalized with dextran, a marker of the macropinocytosis pathway. Thus, these results strongly indicate the involvement of macropinocytosis in E. piscicida entry.

Because internalization of E. piscicida is not completely inhibited by inhibitors related to macropinocytosis, we predicted that E. piscicida also engages other endocytosis mechanisms to facilitate its entry into nonphagocytic cells. Using both pharmacological and shRNA-mediated inhibition of specific endocytic pathways, we subsequently showed that a caveolin-dependent but clathrin-independent pathway is involved in E. piscicida entry. In parallel, dynamin and cholesterol were found to be required for E. piscicida invasion. Collectively, we demonstrated that E. piscicida can use multiple strategies for efficient internalization into host cells. Many pathogens were reported to activate their uptake by different parallel endocytic pathways. For example, both clathrin and caveolin are required for L. monocytogenes internalization (6, 46); clathrin-mediated endocytosis, together with cholesterol, is vital for efficient Francisella tularensis invasion into nonphagocytic cells, which occurs independently of caveolin (7).

In contrast to the internalization mechanisms for HeLa cells described here, E. piscicida was reported to enter macrophage cells via the general phagocytosis pathways mediated by clathrin and caveolin but not by macropinocytosis (20). Here, we also examined the internalization strategies used by E. piscicida using two fish nonphagocytic cell lines, ZF4 and BF-2. Macropinocytosis was confirmed to occur in these two cell lines; however, unexpectedly, the clathrin-mediated pathway was found to be involved in BF-2 cells. These data suggest that E. piscicida utilizes diverse tactics to infect different host cells. Such divergent mechanisms have also been described for the uptake of other pathogens such as Salmonella (47, 48). One explanation for this diversity is that different cell surface receptors and subsequent cell signaling are activated on different cells during interactions with the bacteria.

By combining various strategies, we precisely analyzed each key endocytic pathway involved in E. piscicida internalization. We also determined the mechanisms by which EIB202 enters nonphagocytic cells and identified several cellular molecules and routes. We also evaluated the specificity and functionality of each pathway with three different nonphagocytic cells. Our data demonstrate that EIB202 entry occurs via a process that is not only closely related to macropinocytosis but that is also similar to that used in caveolin-dependent endocytosis; in this process, dynamin and cholesterol are required. Thus, our findings not only provide a detailed understanding of the entry mechanisms of E. piscicida into nonphagocytic cells but also reveal novel cellular factors that may provide new targets for therapies against this pathogen. However, further studies are needed to characterize bacteria virulence factors that interact with components of the macropinocytosis- and caveolin-dependent pathway, which will be useful for vaccine development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The wild-type pathogenic strain of E. piscicida (EIB202) was isolated from ascites fluid of diseased turbot in Yantai (Shandong, China) and EIB202 was grown in tryptic soy broth, tryptic soy agar, or Dulbecco modified essential medium (DMEM) at 30°C. E. coli strains (Top10) were cultured in Luria broth (LB) at 37°C. The plasmids pGFP-uv and pmCherry were used to construct fluorescent strains. The plasmid pCDH-CMV-GFP was used to construct the Rab5-expressing plasmid. The plasmid PLKO.1 was used for shRNA construction. Plasmids pCMV ΔR8.91 and pCMV-VSV-G were used for lentiviral transduction. The information for these plasmids is listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The primers used for shRNA construction are listed in Table S2.

Cell cultures.

HeLa cells and HEK293 T cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in DMEM, BF-2 cells were cultured at 28°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in minimal essential medium, and ZF4 cells were cultured at 28°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in DMEM–F-12 medium. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Pharmacological inhibitors, antibodies, and fluorescent dye.

Pharmacological inhibitors were prepared either in water or in DMSO according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and used at the indicated concentrations. FITC-dextran (70 kDa) and AF-CTxB were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). 5-Ethylisopropyl amiloride (EIPA), NSC23766, LY294002, IPA-3, MK-2206, M-β-CD, nystatin, cholesterol, CD, IPA-3, CPZ, and dynasore were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Specific antibodies against Cav-1 (3238), CHC (4796), and dynamin 2 (2342) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and the antibody against β-actin was purchased from Huabio (M1210; Hangzhou, China).

The fluorescent dyes rhodamine-phalloidin and DAPI were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China).

Cell infection.

Cells were seeded into 24-well plates with 1 × 105 cells per well. Edwardsiella piscicida EIB202 was grown in tryptic soy broth at 30°C with shaking for 12 h and then diluted (1% [vol/vol]) into DMEM for static culture at 30°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.9, while E. coli was grown in LB at 37°C with shaking for 12 h and then diluted (1% [vol/vol]) into DMEM for static culture at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.9. Harvested bacteria were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and added to cells at different MOIs. The plates were then centrifuged at 600 × g and 30°C for 10 min. At the indicated times, cells were treated with 1,000 µg/ml gentamicin for 30 min to kill the bacteria that had adhered to the cell surface, followed by washing with PBS.

To enumerate intracellular bacteria, after a washing step with PBS, Triton X-100 was added to the cell culture at 1% (vol/vol). The yielded lysis mixture was serially diluted and CFU were counted. The results are expressed as intracellular bacteria per well.

For confocal microscopy, HeLa cells were seeded onto 24-well plates containing sterile coverslips at 7 × 104 cells per well. After infection, cells were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 25°C. Fixed cells were washed in PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 25°C. After a washing step with PBS, the actin cytoskeleton was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin for 30 min, and nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) for 10 min at 25°C. Fixed samples were viewed on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Images were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

To evaluate dextran and CTxB uptake, HeLa cells were seeded into 24-well plates containing sterile coverslips at 7 × 104 cells per well, and HeLa cells were pretreated with 2 mg/ml FITC-dextran or 4 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 647-CTxB for 20 min at 37°C before infection. After infection, the cells were placed on ice, washed with PBS, and treated for confocal microscopy.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Monolayers of HeLa cells grown on tissue culture plates were infected with EIB202 (MOI of 300). At the indicated time, the cells were digested by trypsin, and then the cell cultures were collected into tubes and centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min. The cell pellets were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 4 h, washed three times in PBS, fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at 4°C, and washed three times in PBS. Next, the samples were dehydrated in an ethanol gradient from 50 to 100% (concentrations used were 50, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100%) for 20 min every time and then embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were then obtained using an ultramicrotome and double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, the sections were examined.

Lentivirus preparation and infection.

HEK293 T cells were seeded into 10-cm2 dishes at 1 × 106 cells per dish. A Cav-1, CHC shRNA, or Rab5 plasmid was transfected into HEK293 T cells, together with pCMV ΔR8.91 and pCMV-VSV-G, using the calcium phosphate method (double-distilled H2O, CaCl2, and Hanks balanced salt solution [NaCl, KCl, Na2HPO4, glucose, HEPES]). After 9 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 48 h, the supernatant containing lentivirus was harvested and the HeLa cells were infected with the lentiviruses in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM (containing 10% FBS and 1.5 μg/ml puromycin) for another 24 h. The cells were prepared for Western blotting and infection.

Western blotting.

Samples were loaded for 12% SDS-PAGE analysis, transferred to the polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, and probed with anti-Cav-1 antibody, anti-CHC antibody, anti-dynamin 2 antibody, or anti-β-actin antibody.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as the means ± the standard deviations (SD) from triplicate samples per experimental condition unless noted otherwise. Representative results are shown in the figures. Statistical analyses were performed using an unpaired two-tailed Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P values of <0.05 and <0.01.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the NSFC grants 31672696 to J.X., 31472308 to Q.L., and 31622059 to Q.L.

Q.L., T.H., X.L., and D.Y. conceived the study. T.H. performed the majority of experiments. L.Z. participated in Rab-5 colocalization experiments. W.W. and J.X. participated in cell culture experiments. Q.L. and T.H. analyzed all data and wrote the manuscript. Q.L. and Y.Z. critically revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00548-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finlay BB, McFadden G. 2006. Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens. Cell 124:767–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persat A, Nadell CD, Kim MK, Ingremeau F, Siryaporn A, Drescher K, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL, Gitai Z, Stone HA. 2015. The mechanical world of bacteria. Cell 161:988–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonazzi M, Cossart P. 2006. Bacterial entry into cells: a role for the endocytic machinery. FEBS Lett 580:2962–2967. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson JA, Baer SC. 1995. Phagocytosis by zippers and triggers. Trends Cell Biol 5:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veiga E, Cossart P. 2006. The role of clathrin-dependent endocytosis in bacterial internalization. Trends Cell Biol 16:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonazzi M, Veiga E, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Cossart P. 2008. Successive posttranslational modifications of E-cadherin are required for InlA-mediated internalization of Listeria monocytogenes. Cell Microbiol 10:2208–2222. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law HT, Lin AE, Kim Y, Quach B, Nano FE, Guttman JA. 2011. Francisella tularensis uses cholesterol and clathrin-based endocytic mechanisms to invade hepatocytes. Sci Rep 1:192. doi: 10.1038/srep00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuehn MJ. 2000. Bacterial cave dwellers. Trends Microbiol 8:450–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asmat TM, Agarwal V, Saleh M, Hammerschmidt S. 2014. Endocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae via the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor of epithelial cells relies on clathrin and caveolin dependent mechanisms. Int J Med Microbiol 304:1233–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim JP, Gleeson PA. 2011. Macropinocytosis: an endocytic pathway for internalizing large gulps. Immunol Cell Biol 89:836–843. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watarai M, Derre I, Kirby J, Growney JD, Dietrich WF, Isberg RR. 2001. Legionella pneumophila is internalized by a macropinocytotic uptake pathway controlled by the Dot/Icm system and the mouse Lgn1 locus. J Exp Med 194:1081–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watarai M, Makino S, Fujii Y, Okamoto K, Shirahata T. 2002. Modulation of Brucella-induced macropinocytosis by lipid rafts mediates intracellular replication. Cell Microbiol 4:341–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Perez BE, Mondragon-Flores R, Luna-Herrera J. 2003. Internalization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by macropinocytosis in nonphagocytic cells. Microb Pathog 35:49–55. doi: 10.1016/S0882-4010(03)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner A, Mellouk N, Lopez-Montero N, Chang YY, Souque C, Schmitt C, Enninga J. 2016. Macropinosomes are key players in early Shigella invasion and vacuolar escape in epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005602. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung KY, Siame BA, Tenkink BJ, Noort RJ, Mok YK. 2012. Edwardsiella tarda: virulence mechanisms of an emerging gastroenteritis pathogen. Microbes Infect 14:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirai Y, Asahata-Tago S, Ainoda Y, Fujita T, Kikuchi K. 2015. Edwardsiella tarda bacteremia. A rare but fatal water- and foodborne infection: review of the literature and clinical cases from a single centre. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 26:313–318. doi: 10.1155/2015/702615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang IK, Kuo HL, Chen YM, Lin CL, Chang HY, Chuang FR, Lee MH. 2005. Extraintestinal manifestations of Edwardsiella tarda infection. Int J Clin Pract 59:917. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie HX, Lu JF, Rolhion N, Holden DW, Nie P, Zhou Y, Yu XJ. 2014. Edwardsiella tarda-induced cytotoxicity depends on its type III secretion system and flagellin. Infect Immun 82:3436–3445. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01065-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Ni C, Xu W, Dai T, Yang D, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Liu Q. 2016. Intramacrophage infection reinforces the virulence of Edwardsiella tarda. J Bacteriol 198:1534–1542. doi: 10.1128/JB.00978-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sui ZH, Xu H, Wang H, Jiang S, Chi H, Sun L (2017). Intracellular trafficking pathways of Edwardsiella tarda: from clathrin- and caveolin-mediated endocytosis to endosome and lysosome. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:400. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cossart P, Sansonetti PJ. 2004. Bacterial invasion: the paradigms of enteroinvasive pathogens. Science 304:242–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1090124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampath P, Pollard TD. 1991. Effects of cytochalasin, phalloidin, and pH on the elongation of actin filaments. Biochemistry 30:1973–1980. doi: 10.1021/bi00221a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson JA, Watts C. 1995. Macropinocytosis. Trends Cell Biol 5:424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercer J, Helenius A. 2009. Virus entry by macropinocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 11:510–520. doi: 10.1038/ncb0509-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koivusalo M, Welch C, Hayashi H, Scott CC, Kim M, Alexander T, Touret N, Hahn KM, Grinstein S. 2010. Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J Cell Biol 188:547–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green BT, Brown DR. 2006. Differential effects of clathrin and actin inhibitors on internalization of Escherichia coli and Salmonella choleraesuis in porcine jejuna Peyer’s patches. Vet Microbiol 113:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr MC, Teasdale RD. 2009. Defining macropinocytosis. Traffic 10:364–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. 1992. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manser E, Leung T, Salihuddin H, Zhao ZS, Lim L. 1994. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature 367:40–46. doi: 10.1038/367040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karjalainen M, Kakkonen E, Upla P, Paloranta H, Kankaanpää P, Liberali P, Renkema GH, Hyypiä T, Heino J, Marjomäki V. 2008. A Raft-derived, Pak1-regulated entry participates in alpha2beta1 integrin-dependent sorting to caveosomes. Mol Biol Cell 19:2857–2869. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-10-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amyere M, Payrastre B, Krause U, van der Smissen P, Veithen A, Courtoy PJ. 2000. Constitutive macropinocytosis in oncogene-transformed fibroblasts depends on sequential permanent activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phospholipase C. Mol Biol Cell 11:3453–3467. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayascas JR, Alessi DR. 2005. Regulation of Akt/PKB Ser473 phosphorylation. Mol Cell 18:143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothberg KG, Heuser JE, Donzell WC, Ying YS, Glenney JR, Anderson RG. 1992. Caveolin, a protein component of caveolae membrane coats. Cell 68:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cureton DK, Massol RH, Saffarian S, Kirchhausen TL, Whelan SP. 2009. Vesicular stomatitis virus enters cells through vesicles incompletely coated with clathrin that depend upon actin for internalization. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000394. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang LH, Rothberg KG, Anderson RG. 1993. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J Cell Biol 123:1107–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. 2009. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem 78(:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pietiainen V, Marjomaki V, Upla P, Pelkmans L, Helenius A, Hyypia T. 2004. Echovirus 1 endocytosis into caveosomes requires lipid rafts, dynamin II, and signaling events. Mol Biol Cell 15:4911–4925. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-01-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henley JR, Krueger EW, Oswald BJ, McNiven MA. 1998. Dynamin-mediated internalization of caveolae. J Cell Biol 141:85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Praefcke GJ, McMahon HT. 2004. The dynamin superfamily: universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:133–147. doi: 10.1038/nrm1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. 2006. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell 10:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nucci C, da Silveira WD, da Silva Corrêa S, Nakazato G, Bando SY, Ribeiro MA, Pestana de Castro AF. 2002. Microbiological comparative study of isolates of Edwardsiella tarda isolated in different countries from fish and humans. Vet Microbiol 89:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kingstone Chigwechokha P, Tabata M, Shinyoshi S, Oishi K, Araki K, Komatsu M, Itakura T, Shiozaki K. 2015. Recombinant sialidase NanA (rNanA) cleaves α2-3 linked sialic acid of host cell surface N-linked glycoprotein to promote Edwardsiella tarda infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol 47:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okuda J, Kiriyama M, Yamanoi E, Nakai T. 2008. The type III secretion system-dependent repression of NF-κB activation to the intracellular growth of Edwardsiella tarda in human epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett 283:9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips AD, Trabulsi LR, Dougan G, Frankel G. 1998. Edwardsiella tarda induces plasma membrane ruffles on infection of HEp-2 cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett 161:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang B, Yu T, Dong X, Zhang Z, Song L, Xu Y, Zhang XH. 2013. Edwardsiella tarda invasion of fish cell lines and the activation of divergent cell death pathways. Vet Microbiol 163:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veiga E, Cossart P. 2005. Listeria hijacks the clathrin-dependent endocytic machinery to invade mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 7:894–900. doi: 10.1038/ncb1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alpuche-Aranda CM, Berthiaume EP, Mock B, Swanson JA, Miller SI. 1995. Spacious phagosome formation within mouse macrophages correlates with Salmonella serotype pathogenicity and host susceptibility. Infect Immun 63:4456–4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcia-del Portillo F, Finlay BB. 1994. Salmonella invasion of nonphagocytic cells induces formation of macropinosomes in the host cell. Infect Immun 62:4641–4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.