Abstract

Background:

The inadequate reporting of cross-sectional studies, as in the case of the prevalence of Congenital Anomaly, could cause challenges in the synthesis of new evidence and make possible mistakes in the creation of public policies. This study was conducted to critically appraise the quality of the articles involving congenital anomaly prevalence in Iranian infants with the STROBE recommendations.

Methods:

We performed a thorough literature search using the words “congenital anomaly” “birth defect” and “Iran” in MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, SID, Elmnet, Magiran, IranDoc, Iranmedex, and Google Scholar until Aug 2017. In this critical appraisal we focused on cross-sectional studies that reported the prevalence of congenital anomaly in Iranian infants. Data were analyzed using the STROBE score per item and recommendation.

Results:

The results of 17 selected articles on Congenital Anomaly prevalence showed that the overall accordance of the cross-sectional study reports with STROBE recommendations was about 63%. All articles met the recommendations associated with the report of the study’s rationale, objectives, setting, key results and provision of summary measures. Methods and results were the weakest part of the articles, in which recommendations associated with the participant flowchart and missing data analysis were not reported. The recommendations with the lowest scores were those related to the sensitivity analysis (6%, n=1/17), bias (6%, n=1/17), and funding (41%, n=7/17).

Conclusion:

Cross-sectional studies about the prevalence of congenital anomaly in Iranian infants have an insufficient reporting on the methods and results parts. We recognized a clear need to increase the quality of such studies.

Keywords: Iran, Epidemiology, Prevalence, Congenital anomaly, STROBE

Introduction

The insufficient reporting of medical research is a long-lasting and potentially serious universal problem that is not evident to many researchers (1). All scientific study must be fully and precisely reported, letting a proper understanding of their methodology, findings, and repetition of the same if needed (2, 3). However, some of the reports are far from those standards (2). Therefore, many instructions that seek to standardize and progress the reporting quality of different kinds of study were established in the past few years (4).

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) is an instruction whose recommendations have been presented for the purpose of sufficiently report observational studies (cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies) (3,5). STROBE recommendations evaluate the quality of reporting, but not the methodological quality (6). Furthermore, an insufficient reporting of cross-sectional studies could make possible mistakes in the synthesis and acceptance of new evidence and cause inaccuracies in the validation and the creation of public policies (2), particularly in areas with inadequate sources like Iran. For example, the prevalence of Congenital Anomaly (CA) is relevant to public health subjects because it had been related to the main causes of disability and mortality among children in developing countries (7, 8).

CA is the main cause of infant mortality; therefore, 21% of mortality during infancy results from these anomalies (9). This type of anomalies is the fifth leading reason for diminished natural life before the age of 65 and is one of the main causes of disabilities (10, 11). Costs of hospitalization and treatment events for these children carry out a large extra burden on the health system and their families. On the other hand, the diversity of the methods used for diagnosing anomalies and different characteristics of studied populations (live or dead babies) (12–14) related to the inadequate reporting in cross-sectional studies; create mistake when interpreting the actual scope of the problem. For that reason, this study aimed to appraise the reporting quality of cross-sectional studies on the subject of the prevalence of CA in Iranian infants, by the STROBE recommendations as an objective tool.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive study was done in two stages. First, a systematic literature search was carried out to recognize the articles to be taken in the study. Then, the quality of the studies was evaluated with STROBE. This study keeps the recommendations of the PRISMA statement for its reporting (15).

Data sources and search strategy

MEDLINE/PubMed and Scopus were searched for published cross-sectional studies. Search keywords were “Congenital anomaly”, “birth defect”, “prevalence”, and “Iran.” Persian databases (SID, Iranmedex, MagIran, Elmnet, and Iran Doc) and Google Scholar were also searched using equivalent keywords from 2007 until Dec 2017. In addition, reference section of relevant studies was manually checked to identify further studies missed by the electronic search. Authors were contacted for additional missing data. This study was performed independently and simultaneously by three researchers (MI, MHB, and TKH) and a list of found objects was made. Then, search results were assessed, and no differences in the outcome were obtained between the three authors.

Study selection

Full-text articles were assessed by three researchers (MI, MHB, and TKH) and those who met the inclusion criteria were selected. Moreover, a secondary search through the bibliographic references of the chosen articles was done, and duplicates were removed. The inclusion criteria included descriptive and cross-sectional studies on the prevalence of congenital the anomalies among infants in Iran; studies were in English and Persian. The exclusion criteria included those studies that mentioned before publishing STROBE’s statement (Since 2007, STROBE’s statement has been published); studies that investigated the prevalence of congenital anomalies in the animal; qualitative studies, studies presented in conferences; and interventional studies. Short communications, editorials or reviews were excluded.

Instrument

We worked the STROBE items for assessing the quality of the reports. STROBE offers 32 items for the suitable reporting of observational studies. These suggestions express the appropriate method of reporting the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and financing section (5). Based on the language of each reporting, we used the cross-sectional studies suggested-version, available in Persian or English (3). For this study, we operated 28 of the 32 recommendations from cross-sectional studies. We considered as not-applicable the items 16b (continuous variables were not categorized), 16c (the objectives of the studies were not to calculate the report of relative or absolute risk), 12d (sampling strategy was single-stage) and 13b (participation in study does not have multistage stage).

Data extraction

Two methods were used to extract data. The first included information on the general characteristics of each article: first author, name of the study from which the data came from, publication year and language, city, study period, sample size and type of population. The second method is a list of 28 of 32 STROBE items. Three investigators (MI, MHB, and TKH) appraised the full-text of the articles, and the data was extracted. Each researcher considered whether the reports identified met or not the STROBE items. Lastly, the corresponding author of each included article was emailed. In each email, we gave the purpose of the study and the items completed by the article, according to our analysis based on STROBE. This step was performed with the purpose of clarifying potential contrasts with our appraisal. The responses of each author were evaluated based on the methodology expressed above and revisions to our analysis were done as accurate. If no response, a reminder email has been sent 8 d after the first one. We waited for 15 d for the authors to reply, and then our analysis was performed as the ending result.

Analysis

Two kinds of scores were described including score per article and per item. The score per article was described as the number of the STROBE items sufficiently reported, divided by the total of items applicable per article and stated as a percentage. The score per item was described as the number of articles that met each STROBE item, divided by the total of articles for which the item was applicable and stated as a percentage.

Results

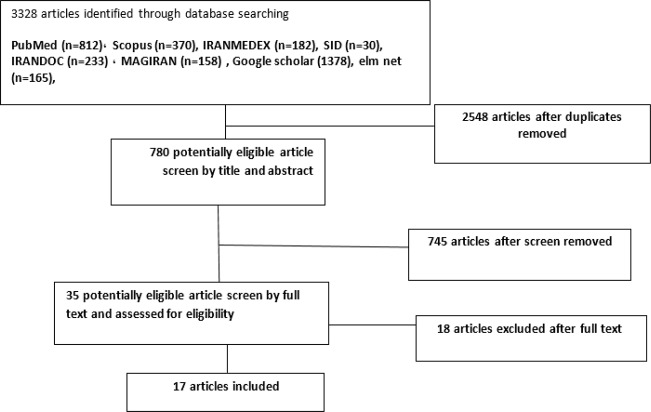

We obtained 3328 articles within the database search. From these articles, 2548 were excluded for being duplicates and 754 were excluded for screen by title and abstract and the remaining 35 were checked in full-text. Of these, 18 were rejected because they did not meet the selection criteria, as a result, 17 articles were obtained for extracting information (16–32) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

Article selection flow chart

General structures of the reports

Table 1 summarizes the main structures of the 17 included articles. Most Publication year of articles related to 2013 (23.5%) and 2014 (18%). Of the total, 5 articles (30%, n=4/17) (16, 19, 23, 27,31) were published in in MEDLINE/PubMed, 4 articles (23.5%, n=4/17) (17, 21, 25, 32) in Scopus, one article (6%, n=1/17) (30) in ISI databases and the others (35%, n=7/17) in Persian databases (SID, Elm net, Magiran, Irandoc, Iranmedex) (18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29). Only one article (6%, n=1/17) (20) had used a statistician in the Author List. Mean±SD of the period of reviewing articles was 6±5.3 months and the maximum period was 26 months (24), and the minimum was 1.5 months (18). These studies were done between 2000 and 2014 and included 189113 participants from different Iranian cities, involving urban and rural population. According to the publication language, six articles (35.3%) were published in English and 11 articles (64.7%) in Persian.

Table 1:

Main structures of the articles about the prevalence of congenital anomaly in Iran

| Authors name | Publication year | Publication language | Study period | City | Population | age | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mashhadi et al (16) | 2014 | English | 2004–2012 | Tabriz | rural | Children(live birth) under eight years of age | 22500 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al (17) | 2013 | Persian | 2007–2008 | Babol | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 1684 |

| Khoshhal-Rahdar et al (18) | 2014 | Persian | 2013–2014 | Dezful | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 4235 |

| Karbasi et al (19) | 2009 | English | October 2003 to June 2004 | Babol | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth and stillbirth) | 4800 |

| Akbarzadeh et al (20) | 2008 | Persian | 2006–2007 | Sabzevar | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 7786 |

| Alijahan et al (21) | 2013 | Persian | 2010–2011 | Ardabil | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 6868 |

| Hosseini et al (22) | 2014 | Persian | 2012 | Sistan | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 1800 |

| Ahmadzadeh et al (23) | 2008 | English | 2003–2006 | Ahwaz | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 4660 |

| Masoodpoor et al (24) | 2013 | Persian | 2007–2008 | Rafsanjan | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 6089 |

| Tayebi et al (25) | 2016 | English | 2008 | Yazd | Urban, rural | Newborn | 1195 |

| Kavianyn et al (26) | 2016 | Persian | 2008–2011 | Golestan | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 92420 |

| Jalali et al (27) | 2011 | Persian | 2011 | Rasht | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 1824 |

| Sarrafan et al (28) | 2011 | Persian | 2006–2007 | Ahvaz | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 5087 |

| Amini Nasab et al (29) | 2014 | Persian | 2007–2011 | Birjand | Urban | Newborn(live birth | 22076 |

| Dastgiri et al (30) | 2007 | English | 2000–2004 | Tabriz | Urban, rural | Newborn | 1574 |

| Rostamizadeh et al (31) | 2017 | English | 2002–2003 2012–2013 |

Azarshahr | Urban, rural | Newborn | 4515 |

| Gheshmi et al (32) | 2012 | Persian | 2007 | Bandar Abbas | Urban, rural | Newborn(live birth | 7007 |

Reporting Quality based on the STROBE items

Eleven (56%) out of the 17 corresponding authors answered, mentioning and supporting if they approved (5/11) or opposed (6/11) with our analysis. Most of the conflicts were found in the items associated with the statistical analysis (the analysis of sensitivity, subgroups and missing data). According to these conflicts, each item was assessed again, and answers were emailed with the respective revisions. Table 2 shows the number of articles that met each STROBE item. The results of 17 selected articles on the prevalence of CA showed that the overall accordance of the cross-sectional study reports with STROBE items was about 63%. The highest score of those articles was 85% (21) and the least score was 42% (28). The most common weakness in the reporting quality was related to methodology and results estimated to be about 54% and 52%, respectively. The items that were fully met were those related to the reporting of the reasons and rationale for the investigation (item 2), to the reporting of the objectives (item 3), to the reporting of the setting (item 5), to provide summary measures (item 15) and summary key results (item 18). On the other hand, the items not reported were those associated with explaining the analysis of the missing data (item 12c), to consider the use of a flowchart for the participants (item 13c) and to indicate the number of participants with missing data for each variable (item 14b). The items with the lowest scores were those associated with the description of the sensitivity analysis (item 12e; 1/13 [6%]), to specify the steps taken to identify possible sources of bias (item 9; 1/17 [6%]) and to give the sources of funding (item 22; 7/17 [41%]).

Table 2:

Number of articles that fulfill each item of the STROBE Statement

| Section | Subsection | Code | item | Fulfill each STROBEitem n% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | 14 (82) | ||

| Title and abstract | Title and abstract | 1b | Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was found | 16(94) |

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | 17 (100) | |

| Introduction | Objectives | 3 | State-specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | 17 (100) |

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | 13(76) | |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection. | 17 (100) | |

| Participants | 6 | Cross-sectional study: give the eligibility criteria and the sources and methods of selection of participants. | 15(85) | |

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable. | 15(88) | |

| Methods | Data sources/ measurement | 8 | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group. | 16(94) |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias. | 1(6) | |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | 13(76) | |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why. | 11(56) | |

| Statistical methods | 12a | Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding. | 10(60) | |

| 12b | Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions. | 1(6) | ||

| 12c | Explain how missing data was addressed. | 0(0) | ||

| 12d | Cross-sectional study: If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | NA | ||

| 12e | Describe any sensitivity analyses. | 1(6) | ||

| Participants | 13a | Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—e.g. numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed | 16(94) | |

| 13b | Give reasons for non-participation at each stage. | NA | ||

| Results | 13c | Consider use of a flow diagram. | 0(0) | |

| Descriptive data | 14a | Give characteristics of study participants (e.g. Demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders. | 15(85) | |

| 14b | Indicate a number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest. | 0(0) | ||

| Outcome data | 15 | Cross-sectional study: report numbers of outcome events or summary measures. | 17(100) | |

| Main results | 16a | Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g. 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included. | 16(94) | |

| 16b | Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized. | NA | ||

| 16c | If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful period. | NA | ||

| Other Analyses | 17 | Report other analyses were done – e.g. Analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses. | 15(85) | |

| Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives. | 17 (100) | |

| Discussion | Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias. | 9(53) |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence. | 15(85) | |

| Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results. | 8(46) | |

| Other information | Funding | 22 | Give the sources of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which present article is based. | 7(41) |

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that the performance of the STROBE items for the reporting of cross-sectional studies on the prevalence of CA was inadequate, the median STROBE score being 63%. Reporting rates were lowest for the methodology and results. These insufficiencies are mainly important for methodologically properly organized studies and correctly analyzed. For that purpose, every precise report, to be reliable, need to afford a strong, complete and obvious showing of what was designed, done and found, that simplify the sufficient understanding and publication of their results (3). Of the 17 articles including 189113 participants, all of them indicated limitations when reporting the methodology associated with the statistical analysis, involving sensitivity analysis, missing data, and sources of bias. Furthermore, the report of the results was not perfect about the explanation of the participant’s flow and participants with missing data for each variable.

The some studies evaluating the quality of observational study reporting, with the STROBE statement as a reference, identified a number of deficiencies harmonious with our results, involving marked insufficiencies in reporting the methodology and results (33–38), such as inadequate reporting in the management of missing data (35,36,39,40) and sources of bias (35,40). Preparing an ideal study report is the main responsibility of the authors, but several methods (editorial board and policies, external reviewers) play an important role in the publication process and also intention to a suitable report (41). To make this objective, the medical journal must follow reporting guidelines such as recommendations as an editorial policy; besides, reviewers and editors must be trained to its right usage (2). In general, the quality of reporting of cross-sectional studies could be enhanced if journals present an active policy of compliance with reporting recommendations such as STROBE (42, 43).

The academic reports make a greater purpose besides the production of new knowledge. Specifically, epidemiological researches have diverse attention, usages, and implications. For a more technical spectator, studies should report detailed estimates of the burden of the diseases that let ranking of public policies. Contrariwise, in case of more general spectators, they should offer a consistent implication about a particular condition. On both stages, technical and general spectators, we found that the articles analyzed about CA in Iran have significant restrictions in its report that reduce the suitable application of their findings.

The limitations of our study are that some of our findings might have been different if they were evaluated by other investigators; however, to prevent subjective decisions, each corresponding author was emailed to confirm our analysis, obtaining a rate response (56%). Additionally, we operated a global score for every article to provide a measure of whole reporting. In selecting this system, we do not suggest that all recommendations are of equal significance. On the other hand, we decided to use these policy help readers have an overall view of the quality of the reports and adherence to the STROBE statement in future studies has the potential to improve study reporting, help the appraisal and analysis of CA by reviewers, readers and journal editors, and finally support the practice of evidence-based medicine.

Conclusion

Cross-sectional studies about the prevalence of CA in Iranian infants have an insufficient reporting of important parts such as methods and results. This finding indication a strong need to enhance the reporting quality of such studies to make its role to sufficiently inform relevant subjects for the putting into practice of public health policies.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all authors of these 17 articles.

Footnotes

Funding

No financial support was received for this study

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Lang TA, Secic M. (2006). How to report statistics in medicine: annotated guidelines for authors, editors, and reviewers. 2nd ed ACP Press, United State of America. New York, pp.: 202–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, et al. (2014). Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet, 383(9913):267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. (2014). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg, 12(12):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannocci A, Saulle R, Colamesta V, et al. (2015). What is the impact of reporting guidelines on Public Health journals in Europe? The case of STROBE, CONSORT and PRISMA. J Public Health (Oxf), 37(4): 737–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. (2007). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology, 18(6):805–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa BR, Cevallos M, Altman DG, et al. (2011). Uses and misuses of the STROBE statement: bibliographic study. BMJ Open, 1(1): e000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shokohi M, Kashani KH. (2001). Prevalence and risk factors of congenital malformations in Hamadan. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci, 12(35):42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irani M, Khadivzadeh T, Nekah A, Mohsen S, Ebrahimipour H, Tara F. (2018). The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. IJOGI, 21(Supple):29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Sadoon I, Hassan G, Yacoub A. (1999). Depleted Uranium and health of people in Basrah: Epidemiological evidence. Incidence and pattern of congenital anomalies among births in Basrah during the period 1990–1998. MJBU, 17:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garry VF, Harkins ME, Erickson LL, et al. (2002). Birth defects, season of conception, and sex of children born to pesticide applicators living in the Red River Valley of Minnesota, USA. Environ Health Perspect, 110 Suppl 3: 441–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farhud D, Walizadeh GR, Kamali MS. (1986). Congenital malformations and genetic diseases in Iranian infants. Hum Genet, 74 (4): 382–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farhud D. (1997). Evidence for a New AD Syndrome: Report of a Large Iranian Sibship with Severe Multiple Synostosis. Iran J Public Health, 26(1–2): 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farhud D, Hadavi V, Sadighi H. (2000). Epidemiology of neural tube defects in the world and Iran. Iran J Public Health, 29(1–4): 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afshar M, Golalipour MJ, Farhud D. (2006). Epidemiologic aspects of neural tube defects in South East Iran. Neurosciences (Riyadh), 11(4): 289–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashhadi Abdolahi H, Kargar Maher MH, Afsharnia F, Dastgiri S. (2014). Prevalence of congenital anomalies: a community-based study in the Northwest of Iran. ISRN Pediatr, 2014:920940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadzadeh I, Sorkh H, Alizadeh-Navaei R. (2013). Prevalence of external congenital malformations in neonates born in Mehregan Hospital, North of Iran. Genetics In The 3rd Millennium, 11(1):2990–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoshhal-Rahdar F, Saadati H, Mohammadian M, et al. (2014). The Prevalence of Congenital Malformationsin Dezful-2012. Genetics In The 3rd Millennium, 12(2):3622–31. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karbasi SA, Golestan M, Fallah R, et al. (2009). Prevalence of congenital malformations. Acta Med Iran, 47(2):149–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbarzadeh R, Rahnama F, Hashemian M, Akaberi A. (2008). The incidence of apparent congenital anomalies in neonates in mobini maternity hospital in sabzevar, iran in 2005–6. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, 15 (4): 231–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alijahan R, Mirzarahimi M, Ahmadi-Hadi P, Hazrati S. (2013). Prevalence of Congenital Abnormalities and Its Related Risk Factors in Ardabil, Iran, 2011. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility, 16 (54): 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosseini S, Nikravesh A, Hashemi Z, Rakhshi N. (2014). Race of apparent abnormalities in neonates born in Amir-almomenin hospital of Sistan. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci, 6(3):753–579. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmadzadeh A, Zahad S, Masoumeh A, Azar A. (2008). Congenital malformations among live births at Arvand Hospital, Ahwaz, Iran-A prospective study. Pak J Med Sci, 24(1):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masoodpoor N, Arab-Baniasad F, Jafari A. (2013). Prevalence and pattern of congenital malformations in newborn in Rafsanjan, Iran (2007–08). J Gorgan Univ Med Sci, 15(3):114–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tayebi N, Yazdani K, Naghshin N. (2010). The prevalence of congenital malformations and its correlation with consanguineous marriages. Oman Med J, 25(1):37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kavianyn N, Mirfazeli A, Aryaie M, et al. (2016). Incidence of birth defects in Golestan province. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci, 17(4): 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jalali S, Fakhraie S, Afjaei S, Kazemian M. (2011). The incidence of obvious congenital abnormalities among the neonates born in rasht hospitals in 2011. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci, 19 (2): 109–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarrafan N, Mahdi-nasab A, Arastoo L. (2011). Evaluation of prevalance of congenital upper- and lower extremity abnormalies in neonatal live births in Imam and Razi hospital of Ahvaz. Jundishapur Sci Med J, 10 (70): 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amini Nasab Z, Aminshokravi F, Moodi M, et al. (2014). Demographical condition of neonates with congenital abnormalities under Birjand city health centers during 2007–2012. J Birjand Univ Med Sci, 21 (1): 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dastgiri S, Imani S, Kalankesh L, Barzegar M, Heidarzadeh M. (2007). Congenital anomalies in Iran: a cross-sectional study on 1574 cases in the North-West of country. Child Care Health Dev, 33 (3): 257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rostamizadeh L, Bahavarnia SR, Gholami R. (2017). Alteration in incidence and pattern of congenital anomalies among newborns during one decade in Azarshahr, Northwest of Iran. IJER, 4(1):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gheshmi AN, Nikuei P, Khezri M, et al. (2012). The frequency of congenital anomalies in newborns in two maternity hospitals in Bandar Abbas: 2007–2008. Genet 3rd Millennium, 9 (4): 2554–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tapia JC, Ruiz EF, Ponce OJ, Malaga G, Miranda J. (2015). Weaknesses in the reporting of cross-sectional studies according to the STROBE statement: the case of metabolic syndrome in adults from Peru. Colomb Med (Cali), 46(4):168–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Altman DG, Vandenbroucke JP. (2007), Commentary: strengthening the reporting of observational epidemiology the STROBE statement. Int J Epidemiol, 36(5): 948–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung AE, Palanki R, Bakri SJ, Depperschmidt E, Gibson A. (2009). Applying the CONSORT and STROBE statements to evaluate the reporting quality of neovascular age-related macular degeneration studies. Ophthalmology, 116(2): 286–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller M, Egger M. (2009). Strengthening the reporting of observational epidemiology (STROBE) in sexual health. Sex Transm Infect, 85(3): 162–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papathanasiou AA, Zintzaras E. (2010). Assessing the quality of reporting of observational studies in cancer. Ann Epidemiol, 20(1): 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeelani A, Malik W, Haq I, Aleem S, Mujtaba M, Syed N. (2014). Cross-sectional studies published in Indian journal of community medicine: evaluation of adherence to strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology statement. Ann Med Health Sci Res, 4(6): 875–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langan S, Schmitt J, Coenraads P-J, Svensson Å, von Elm E, Williams H. (2010). The reporting of observational research studies in dermatology journals: a literature-based study. Arch Dermatol, 146(5):534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poorolajal J, Cheraghi Z, Irani AD, Rezaeian S. (2011). Quality of cohort studies reporting post the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. Epidemiol Health, 33: e2011005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glujovsky D, Villanueva E, Reveiz L, Murasaki R. (2014). Adherencia a las guías de informe sobre investigaciones en revistas biomédicas en América Latina y el Caribe. Rev Panam Salud Publica, 36(4): 232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pouwels KB, Widyakusuma NN, Groenwold RH, Hak E. (2016). Quality of reporting of confounding remained suboptimal after the STROBE guideline. J Clin Epidemiol, 69:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hopewell S, Ravaud P, Baron G, Boutron I. (2012). Effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on the reporting of abstracts in high impact medical journals: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ, 344: e4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]