Abstract

Background:

An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is a well-established risk factor for the long-term development of radio-graphic osteoarthritis (OA). However, little is known about the early degenerative changes (ie, <5 years after injury) of individual joint features (ie, cartilage, bone marrow), which may be reversible and responsive to interventions.

Purpose:

To describe early degenerative changes between 1 and 5 years after ACL reconstruction (ACLR) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and explore participant characteristics associated with these changes.

Study Design:

Case-control study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

Seventy-eight participants (48 men; median age, 32 years; median body mass index [BMI], 26 kg/m2) underwent 3.0-T MRI at 1 and 5 years after primary hamstring autograft ACLR. Early tibiofemoral and patellofemoral OA features were assessed with the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score. The primary outcome was worsening (ie, incident or progressive) cartilage defects, bone marrow lesions (BMLs), osteophytes, and meniscal lesions. Logistic regression with generalized estimating equations evaluated participant characteristics associated with worsening features.

Results:

Worsening of cartilage defects in any compartment occurred in 40 (51%) participants. Specifically, worsening in the patellofemoral and medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartments was present in 34 (44%), 8 (10%), and 10 (13%) participants, respectively. Worsening patellofemoral and medial and lateral tibiofemoral BMLs (14 [18%], 5 [6%], and 10 [13%], respectively) and osteophytes (7 [9%], 8 [10%], and 6 [8%], respectively) were less prevalent, while 17 (22%) displayed deteriorating meniscal lesions. Worsening of at least 1 MRI-detected OA feature, in either the patellofemoral or tibiofemoral compartment, occurred in 53 (68%) participants. Radiographic OA in any compartment was evident in 5 (6%) and 16 (21%) participants at 1 and 5 years, respectively. A high BMI (>25 kg/m2) was consistently associated with elevated odds (between 2- and 5-fold) of worsening patellofemoral and tibiofemoral OA features.

Conclusion:

High rates of degenerative changes occur in the first 5 years after ACLR, particularly the development and progression of patellofemoral cartilage defects. Older patients with a higher BMI may be at particular risk and should be educated about this risk.

Keywords: knee, anterior cruciate ligament, osteoarthritis, cartilage

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (ACLR) is often performed with the intention to improve the stability of a mechanically unstable ACL-deficient knee, facilitate a return to competitive sports, and reduce the risk of subsequent meniscal or cartilage damage.8,31,50 While typically restoring mechanical stability, ACLR does not protect against the long-term development of knee osteoarthritis (OA).21,32 Radiographic knee OA is evident in as many as 50% to 90% of patients 10 to 15 years after an ACL injury, regardless of treatment, and often with an onset during early adulthood.32

With rates of ACL injuries continuing to rise,47 secondary prevention strategies to delay or halt OA onset after an injury are vital.43 Unlike established radiographic OA, the trajectory of early pre radiographic stages of disease, such as posttraumatic changes to cartilage and bone marrow, has the capacity to be modified.40,44 This is particularly pertinent for posttraumatic OA, which is often evident 15 years earlier than primary OA,32 resulting in substantial and prolonged effects on quality of life19 and the risk of early knee arthroplasty.7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to identify and monitor early structural changes to all joint tissues. While radiography can detect osteophytes, joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts, MRI is more sensitive to changes in early OA features such as cartilage, particularly during shorter follow-up periods.2,25,27 Longitudinal changes to MRI-detected OA features have focused on cartilage degeneration within the acute recovery phase after ACLR (ie, first 1–2 years),52,54 mostly assessed and observed in the tibiofemoral compartment. In the patellofemoral joint, the trochlea is at greatest risk of early degeneration within the first 2 years after an ACL injury,10,20 which may contribute to high rates of longer-term radiographic patellofemoral OA.11 Identifying patients with progressive early OA features after natural biological graft healing and functional rehabilitation (>2 years after injury), but before established joint disease, may present opportunities to develop secondary prevention strategies.

Therefore, the primary aims of this study were to (1) describe longitudinal changes to early OA features on MRI from 1 to 5 years after ACLR and (2) determine the association between participant characteristics (age, sex, body mass index [BMI], time from injury to surgery, meniscectomy/cartilage defects at the time of ACLR, anteroposterior knee laxity) and changes in MRI findings. Second, we evaluated longitudinal changes in radiographic OA between 1 and 5 years in both knees.

METHODS

Participants

All 111 consecutively recruited patients (median age at the time of surgery, 26 years [range, 18–50 years]) who participated in our previously reported MRI evaluation at 1 year after ACLR10 (ie, baseline for the current study) were eligible for the current study. Baseline inclusion and exclusion criteria, ACLR technique, and postoperative rehabilitation are described in a previous publication.10 Briefly, baseline inclusion criteria included primary single-bundle hamstring autograft ACLR by 1 of 2 orthopaedic surgeons (T.W., H.M.) in Melbourne, Australia. Baseline exclusion criteria included knee injuries/symptoms/surgery before the ACL injury, >5 years between the ACL injury and ACLR, and any secondary injury/surgery to the ACLR knee (between surgery and 1-year assessment). A secondary injury was defined as a new index or contralateral knee injury (ACL, meniscus, collateral ligament), surgery, or intra-articular knee injection. Patients with a secondary injury between 1 and 5 years were invited to participate at 5 years after ACLR follow-up, as this is a common occurrence and representative of the wider ACLR population. Of the 111 participants with baseline MRI data, 78 (70%) (48 men; median age, 32 years [range, 23–56 years]) completed an MRI assessment at follow-up (median, 5.2 years after ACLR [range, 4.7–6.3 years]). Ethical approval was granted by La Trobe University’s Human Ethics Committee (HEC 15–100), and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Demographic, Injury, and Surgical Factors

Participant age, sex, ACL injury history (date of ACL injury, time from injury to surgery), and previous activity level were obtained at the baseline assessment. Activity level was defined as level 1 (pivoting/jumping sports) to level 4 (sedentary).22 Participant BMI was calculated at baseline and follow-up. Information on meniscectomy and significant cartilage defects assessed at the time of surgery were obtained from surgical records at baseline, and these were termed “combined injuries.” Arthroscopically identified cartilage defects were defined as significant when the Outerbridge grade was ≥2 (ie, at least partial-thickness defect).36 Anteroposterior laxity at baseline was assessed using the KT-1000 arthrometer (MEDmetric) at 30° of flexion with a 30-lb load.13 Participants were questioned about new injuries or surgery between baseline and follow-up. Participants with new index or contralateral knee injuries/surgery were included, as this is a common occurrence and representative of the wider ACLR population. Tibiofemoral and patellofe-moral radiographic OA in the ACLR and contralateral knees was determined at baseline and follow-up using previously published protocols10 and Osteoarthritis Research Society International atlas definitions1 (see the Appendix, available in the online version of this article). Bilateral posteroanterior and lateral weightbearing and nonweightbearing skyline views were taken. Radiographic OA was defined as (1) joint space narrowing of grade ≥2, (2) sum of osteophytes ≥2, or (3) grade 1 osteophyte in combination with grade 1 joint space narrowing.1

MRI Acquisition and Interpretation

All participants underwent unilateral knee MRI at baseline using a single 3.0-T system (Achieva; Philips), as previously described.10 The same MRI scanner was used to acquire follow-up scans of the ACLR knee, with identical sequences to those obtained at baseline. The sequences consisted of 3-dimensional proton density-weighted volume isotropic turbo spin echo acquisition (VISTA) at 0.35 mm, short tau inversion recovery (STIR), and axial proton density-weighted turbo spin echo. All MRI scans were evaluated using the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) by a single musculoskeletal radiologist (A.G.) with 14 years of experience and established interrater and intrarater reliability (kappa, 0.61–0.80) by a semiquantitative MRI assessment.26 The radiologist evaluated the baseline and follow-up scans paired (not blinded to the time points of MRI) but blind to clinical/radiographic information. The MOAKS divides the knee into 14 articular subregions to score cartilage defects (assessed using the VISTA sequence) and bone marrow lesions (BMLs) (assessed using STIR and fluid-sensitive turbo spin echo sequences) and 6 tibiofemoral and 6 patellofemoral subregions to score osteophytes.26 Meniscal lesions were scored separately for the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus and divided into anterior, posterior, and central subregions for each meniscus. Cartilage defects were graded from 0 to 3 based on size (percentage of the surface area relative to each subregion) and depth (percentage of the lesion that is full thickness). Size was graded as the following: 0 = none; 1 = <33%; 2 = 33%−66%; and 3 = >66%. Depth was graded as the following: 0 = no full-thickness loss; 1 = <10%; 2 = 10%−75%; and 3 = >75%. BMLs were based on size only (percentage of the surface area affected relative to each subregion): 0 = none; 1 = <33%; 2 = 33%−66%; and 3 = >66%. Osteophytes were graded according to size based on how far they extended from the joint: 0 = none; 1 = small; 2 = medium; and 3 = large. Given that the definition of a definite osteophyte has not been delin-eated,26 we considered an osteophyte present if it was scored ≥2. Meniscal tears were described as absent or present and by type (vertical, horizontal, or complex). Meniscal maceration was described as absent or present and by type (partial, complete, or progressive). Meniscal extrusion was described by size: 0 = <2 mm; 1 = 2–2.9 mm; 2 = 3–4.9 mm; and 3 = ≥5 mm. Hoffa fat pad synovitis was graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe). More information on the MRI sequences used and the MOAKS scoring system appears in the Appendix.

Definition of Worsening OA Features

Subregions were combined to define 3 compartments: patellofemoral (patella and trochlea), medial tibiofemoral (medial femur: central and posterior; medial tibia: anterior, central, and posterior), and lateral tibiofemoral (lateral femur: central and posterior; lateral tibia: anterior, central, and posterior). Worsening of OA features in each compartment was defined as any increase in the score (in any corresponding subregions for that compartment). Therefore, either progression of an OA feature (ie, increase in defect severity) or a new OA feature (ie, from no defect to present defect) from baseline to follow-up was classified as worsening. This definition is reliable and sensitive to changes in ACL-injured patients and other populations at high risk for OA.45,54 Increase in defect severity was defined as an increase in the size or depth of the lesion of at least 1 point on the MOAKS. New lesions were defined as those with size 0 at baseline and size ≥1 at follow-up (osteophytes needed to be ≥2 at follow-up, as the definition of an osteophyte has not been delineated).26

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to define worsening of MRI- detected OA features for each compartment and radiographic OA. Both the medial and lateral patellar and trochlear subregions were included in analyses for patellofemoral compartment outcomes (4 observations per knee). The medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartments had 5 observations per knee (femur: central and posterior; tibia: anterior, central, and posterior). Logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations (GEEs) (to account for correlations between subregions within the same compartment) were used to determine if participant characteristics (age, sex, BMI at baseline, time from injury to surgery, meniscectomy and cartilage defects at the time of ACLR, reinjury, and anteroposterior knee laxity) were associated with worsening OA features. Age and time from injury to ACLR were dichotomized at their median values, while BMI was dichotomized based on the established overweight cutoff of 25 kg/m2 (median at baseline, 25.3 kg/m2), so that odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs could be estimated and descriptively compared with the nominal variable of concomitant injuries. Univariate regression analysis was performed initially; participant characteristics with a P value <.20 were entered into a multivariate logistic regression GEE model to calculate ORs and 95% CIs. The McNe-mar test was used to determine any significant change in repeated-measures nominal data (ie, worsening radiographic OA from baseline to follow-up). Stata v 14.2 (Stata-Corp) was used for statistical analyses. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants

Characteristics of the 78 participants included in the current study are presented in Table 1. Apart from medial meniscal lesions, which were more prevalent in the participating group at baseline, there were no demographic, surgical, or baseline MRI-related differences between those who did and did not participate in the follow-up assessment at 5 years (P > .05) (Tables 1 and 2). Thirty-eight of the 78 participants (49%) had a combined injury (arthroscopic meniscectomy/cartilage defect at the time of index surgery), and 12 (15%) participants reported a new index knee injury/surgery between baseline and follow-up (revision ACLR: n = 3; partial meniscectomy: n = 6; intra-articular injection: n = 1; collateral ligament injury: n = 2). Six participants had a new contralateral knee injury (ACLR: n = 3; meniscectomy: n = 1; collateral ligament injury: n = 1; investigative arthroscopic surgery: n = 1).

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics at 1 and 5 Years After ACLRa

| No Follow-upb (n = 33) | Follow-up (n = 78) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 1 y | 5 y | |

| Age, y | 27 (13) [20 to 50] | 28 (15) [19 to 52] | 32 (15) [23 to 56] |

| Male sex, n (%) | 23 (70) | 48 (62) | 48 (62) |

| Activity level before injury, c n (%) | |||

| Level 1 | 26 (79) | 54 (69) | 54 (69) |

| Level 2 | 5 (15) | 18 (23) | 18 (23) |

| Level 3 | 2 (6) | 6 (8) | 6 (8) |

| Level 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Activity level at time of MRI, c n (%) | |||

| Level 1 | 9 (27) | 19 (24) | 25 (32) |

| Level 2 | 4 (12) | 10 (13) | 11 (14) |

| Level 3 | 8 (24) | 19 (24) | 32 (41) |

| Level 4 | 12 (37) | 30 (39) | 10 (13) |

| Time to surgery, wk | 12 (13) [3 to 241] | 14 (20) [1 to 231] | 14 (20) [1 to 231] |

| Body mass index,d kg/m2 | 26 (7) [20 to 37] | 25 (5) [20 to 37] | 26 (5) [20 to 35] |

| Concomitant injuries/procedures at time of ACLR, n (%) | |||

| Medial meniscectomy/repair | 7 (21)/3 (9) | 16 (21)/9 (12) | 16 (21)/9 (12) |

| Lateral meniscectomy/repair | 5 (15)/2 (6) | 18 (23)/1 (1) | 18 (23)/1 (1) |

| Patellofemoral cartilage defecte | 5 (15) | 7(9) | 7(9) |

| Medial tibiofemoral cartilage defecte | 3 (9) | 7 (9) | 7 (9) |

| Lateral tibiofemoral cartilage defecte | 3 (9) | 4 (5) | 4 (5) |

| Anteroposterior laxity (between-limb difference),f mm | 1.3 (2.3) [−3.8 to 7.2] | 1.6 (2.9) [−1.9 to 3.5] | NA |

| IKDC score | 84 (14) [53 to 98] | 87 (16) [54 to 100] | 91 (15) [53 to 100] |

Values are shown as median (interquartile range) [range] unless otherwise specified. ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available.

Reasons for exclusion: pregnant (n = 1), unable to contact (n = 10), unable to attend because of distance/time (n = 17; interstate: n = 5, overseas: n = 4), ruled out by participating surgeon because of conflict with participation in other study (n = 4), and incorrect limb scanned (n = 1).

Classification based on Grindem et al22: level 1, jumping, cutting, and pivoting sports; level 2, lateral movement sports; level 3, straight line activities; and level 4, sedentary.

n = 72 at follow-up (ie, those who participated in follow-up clinical testing).

Outerbridge grade ≥2 assessed arthroscopically.

Assessed using the KT-1000 arthrometer. Not included in 5-year clinical testing measures.

TABLE 2.

Imaging Results at 1 and 5 Years After ACLRa

| No Follow-up (n = 33) | Follow-up (n = 78) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 1 y | 5 yb | |

| MRI-detected OA featuresc | |||

| Cartilage defect (grade ≥1, full- or partial-thickness) | |||

| Patellofemoral | 13 (39) | 37 (48) | 47 (60) |

| Medial tibiofemoral | 9 (27) | 23 (29) | 28 (36) |

| Lateral tibiofemoral | 11 (33) | 18 (23) | 26 (33) |

| Bone marrow lesion (grade ≥1) | |||

| Patellofemoral | 6 (18) | 20 (26) | 18 (23) |

| Medial tibiofemoral | 4 (12) | 14 (18) | 13 (17) |

| Lateral tibiofemoral | 8 (24) | 14 (18) | 16 (21) |

| Osteophyte (grade ≥2)d | |||

| Patellofemoral | 0(0) | 3 (4) | 7 (9) |

| Medial tibiofemoral | 0(0) | 1 (1) | 10 (12) |

| Lateral tibiofemoral | 2 (6) | 6 (8) | 9(12) |

| Meniscal lesion (grade ≥1)e | |||

| Medial tibiofemoral | 18 (55)f | 52 (67) | 53 (68) |

| Lateral tibiofemoral | 20 (60) | 38 (49) | 40 (52) |

| Hoffa fat pad synovitis (grade ≥1) | 20 (60) | 47 (60) | 69 (88) |

| Radiographic OAg | |||

| Patellofemoral (ACLR/contralateral limb) | 1 (3)/2 (6) | 4 (5)/2 (3) | 14 (18)/4 (5) |

| Medial tibiofemoral (ACLR/contralateral limb) | 1 (3)/1 (3) | 2 (3)/2 (3) | 4 (5)/2 (3) |

| Lateral tibiofemoral (ACLR/contralateral limb) | 2 (6)/0 (0) | 1 (1)/1 (1) | 4 (5)/1 (1) |

Values are shown as n (%). ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OA, osteoarthritis.

Three participants underwent MRI on a different scanner at follow-up because of being interstate.

The MRI OA Knee Score (MOAKS) was used to grade each feature.26

Given that the definition of a definite osteophyte has not been delineated, we considered an osteophyte to be present if it was graded ≥2.

Includes tearing (vertical/horizontal/complex), maceration (partial/degenerative), or extrusion.

Statistically significant (P < .05) compared with the follow-up group.

Radiographic OA was defined as (1) joint space narrowing of grade ≥2, (2) sum of osteophytes ≥2, or (3) grade 1 osteophyte in combination with grade 1 joint space narrowing.1

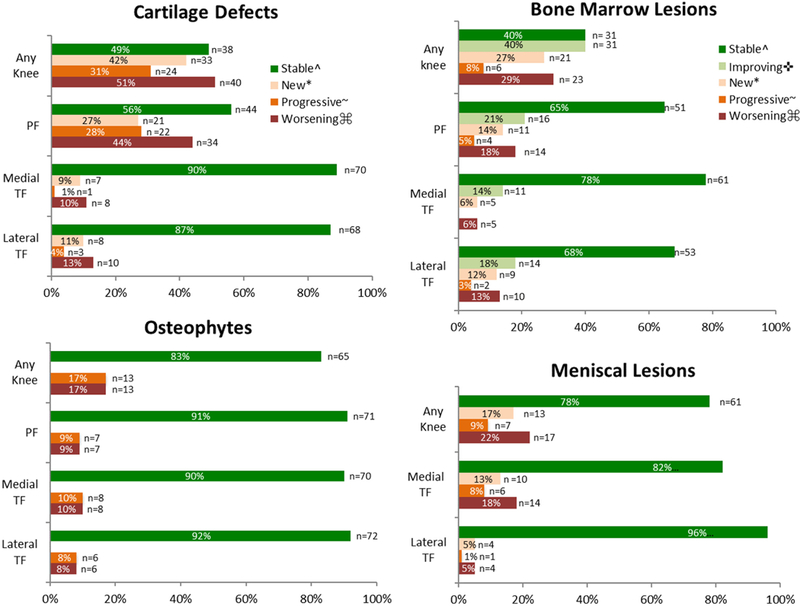

Cartilage Defects

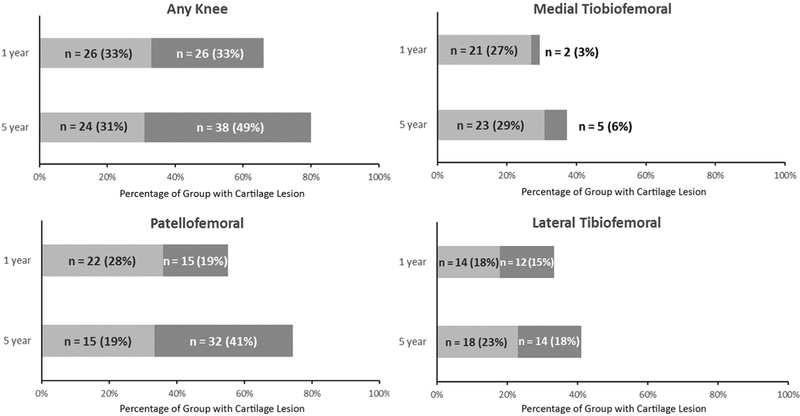

Worsening of cartilage defects in any compartment occurred in 40 (51%) participants, with worsening most commonly occurring in the patellofemoral compartment (n = 34 [44%]) (Figure 1). Medial and lateral tibiofemoral cartilage worsening occurred in 8 (10%) and 10 (13%) participants, respectively (Figure 1). Twenty-five (63%) of those with cartilage worsening had isolated patellofemoral cartilage worsening compared with 6 (15%) who had isolated tibiofemoral cartilage worsening. The prevalence of participants with a patellofemoral full-thickness cartilage defect more than doubled from baseline to follow-up (n = 15 [19%] to n = 32 [41%]) (Figure 2). The prevalence of those with full-thickness cartilage defects also increased from baseline to follow-up in the medial (n = 2 [3%] to n = 5 [6%]) and lateral tibiofemoral (n = 12 [15%] to n = 14 [18%]) compartments (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Worsening of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-detected osteoarthritis features from baseline (1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [ACLR]) to follow-up (5 years after ACLR). Worsening meniscal lesions include worsening tear, maceration, and extrusion. PF, patellofemoral compartment; TF, tibiofemoral compartment.

^ Stable lesions = participants with no worsening (i.e., no new or progressive features, or BML improvement)

* New = participants with no lesion at baseline (ie, MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score [MOAKS] size score = 0), with score of ≥1 at follow-up for cartilage defects, bone marrow lesions (BMLs) and meniscal lesions (≥2 for osteophytes).

~ Progressive = participants with a lesion at baseline (ie, MOAKS size score >1), with an increase in severity of lesion (ie, at least a 1-point increase in size or depth of lesion).

⌘ Worsening = participants with either progressive or new feature.

✜ Improving = participants with a BML at baseline (ie, MOAKS score ≥1), with a decrease in severity of BML (ie, at least a 1 -point decrease in size of BML).

Figure 2.

Cartilage worsening (increase in the number and severity of defects) in the patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joints at baseline and follow-up. Light grey shading indicates the number of participants with a partial-thickness defect (in absence of a full-thickness defect). Dark grey shading indicates the number of participants with a full-thickness cartilage defect.

Bone Marrow Lesions

Although the frequency of any BMLs remained the same (47%) from baseline to follow-up (Table 2), worsening of BMLs in any compartment occurred in 23 (29%) participants (Figure 1). This was caused by new or progressive lesions in one compartment, with concurrent improvement in BMLs in another compartment. Patellofemoral and medial and lateral tibiofemoral BML worsening occurred in 14 (18%), 5 (6%), and 10 (13%) participants, respectively (Figure 1). Improvement of BMLs in any compartment occurred in 31 (40%) participants from baseline to follow-up. Patellofemoral, medial tibiofemoral, and lateral tibiofemoral BML improvement occurred in 16 (21%), 11 (14%), and 14 (18%) participants, respectively (Figure 1).

Osteophytes

Worsening of osteophytes in any compartment occurred in 13 (17%) participants (Figure 1). Patellofemoral, medial tibiofemoral, and lateral tibiofemoral osteophyte worsening occurred in 7 (9%), 8 (10%), and 6 (8%) participants, respectively. All worsening was caused by progressive lesions (increase in size), with no new osteophytes (grade ≥2) at follow-up (Figure 1).

Meniscal Lesions

The prevalence of medial and lateral meniscal lesions only increased by 1% and 3%, respectively, from baseline to follow-up (Table 2). However, worsening of meniscal lesions (increase in size) occurred in the medial or lateral compartment in 17 (22%) participants, with 14 (18%) and 4 (5%) occurring in the medial and lateral compartments, respectively (Figure 1).

Radiographic OA

The prevalence of radiographic OA increased significantly from baseline to follow-up in the patellofemoral compartment in the ACLR knee (n = 4 [5%] to n = 14 [18%]; P < .05) but not in the contralateral knee (n = 2 [3%] to n = 4 [5%]; P > .05). Smaller and nonsignificant increases were seen in the ACLR and contralateral medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartments (Table 2).

Factors Associated With Worsening MRI-Detected OA Features

In multivariate analyses, participants with a baseline BMI >25 kg/m2 consistently displayed 2 to 5 times greater odds of worsening of all MRI-detected OA features (except for patellofemoral BMLs) (Tables 3 and 4). All participants with a baseline BMI >25 kg/m2 had worsening patellofemoral osteophytes. Older age (>26 years) at the time of surgery was related to greater odds of worsening patellofemoral cartilage defects (OR, 4.19 [95% CI, 1.78–9.86]). Although ACLR performed >3 months after the injury had greater odds of worsening tibiofemoral osteophytes (OR, 3.91 [95% CI, 1.04–14.66]) and meniscal lesions (OR, 6.35 [95% CI, 1.38–29.29]) (Table 3), it had lower odds of patellofemoral cartilage defect worsening (OR, 0.44 [95% CI, 0.21–0.94]) (Table 4). Anteroposterior knee laxity (>3-mm between-limb difference) was related to 4 times greater odds of worsening meniscal lesions (OR, 4.51 [95% CI, 1.35–15.10]). As we were unable to assess the effect of reinjuries because of the small number of reinjuries in the index knee (n = 12), a sensitivity analysis excluding participants with a reinjury was performed. This sensitivity analysis resulted in similar effect sizes (but wider 95% CIs), suggesting that the effect of reinjuries on worsening MRI features in this study was minimal. A combined injury (meniscectomy/cartilage defect at the time of ACLR) was not significantly associated with increased odds of worsening MRI-detected OA features in the regression analysis (Tables 3 and 4). However, the relatively small number of patients with worsening of some OA features detrimentally affected the stability of the regression analysis. Therefore, we performed a second sensitivity analysis, comparing the rate of worsening MRI-detected OA features between those with a combined injury (n = 38) and isolated injury (n = 40). The rates of any MRI-detected OA feature worsening were significantly greater in those with a combined injury than in those with an isolated injury (31/38 vs 22/40, respectively; chi-square, P = .012). In addition, to determine the effect of pre-existing OA, we performed a third sensitivity analysis by excluding patients with radiographic OA (as described in Table 1) at 1 year after ACLR (n = 5). Additional analyses comparing the worsening rates in the patients with (n = 5) and without radiographic OA (n = 73) at 1 year revealed similar (and nonsignificantly different) rates of MRI-detected OA feature worsening, except for tibiofemoral osteophytes (2/5 vs 7/73, respectively; chi-square, P = .112).

TABLE 3.

Demographic and Surgical Factors Associated With Worsening Tibiofemoral MRI-Detected OA Featuresa

| Cartilage Defectb |

Bone Marrow Lesionc |

Osteophyted |

Meniscal Lesione |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Prevalence of worsening, n (%) | 16/78 (21) | 12/78 (15) | 9/78 (12) | 17/78 (22) | ||||

| Age at time of surgeryf (reference: ≤26 y) | 3.17 (1.04–9.66) | 3.27 (0.92–11.60) | 0.94 (0.27–3.33) | 1.82 (0.26–12.49) | 0.50 (0.18–1.43) | 0.39 (0.12–1.24) | ||

| Sex (reference: female) | 0.86 (0.29–2.57) | 0.39 (0.12–1.28) | 0.59 (0.20–1.79) | 1.03 (0.22–4.90) | 1.07 (0.38–3.05) | |||

| Body mass indexg (reference: ≤25 kg/m2) | 2.77 (0.86–8.96) | 2.96 (0.81–10.79) | 5.29 (1.45–19.34) | 4.58 (1.36–15.49) | 2.67 (0.49–14.43) | 3.79 (1.02–14.03) | 4.62 (1.57–13.55) | |

| Time from injury to ACLRf (reference: ≤3 mo) | 2.77 (0.97–7.88) | 2.47 (0.83–7.40) | 1.11 (0.31–3.96) | 4.56 (1.20–17.37) | 3.91 (1.04–14.66) | 3.79 (1.02–14.03) | 6.35 (1.38–29.29) | |

| Meniscectomyh | 1.99 (0.70–5.64) | 0.90 (0.27–3.03) | 1.62 (0.48–5.51) | 1.50 (0.31–7.17) | 0.86 (0.30–2.41) | |||

| Cartilage defecti | 1.73 (0.50–5.92) | 1.21 (0.36–4.03) | 1.97 (0.30–12.76) | 0.75 (0.18–3.04) | ||||

| Anteroposterior laxityj (reference: ≤3-mm between-limb difference) | 1.03 (0.37–2.85) | 0.34 (0.04–2.61) | 0.13 (0.02–1.09) | 0.17 (0.02–14.67) | 2.15 (0.73–6.26) | 4.51 (1.35–15.10) | ||

Values are shown as odds ratios (95% CI) unless otherwise specified. Univariate regression analysis was performed initially; participant characteristics with a P value <.20 were entered into a multivariate logistic regression generalized estimating equation model to calculate odds ratios and 95% CIs. An odds ratio >1 represents greater odds of the MRI-detected OA feature in the presence of the demographic/surgical factor. Bold values indicate a significant association (P < .05). ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OA, osteoarthritis.

Ten subregions per participant.

Ten subregions per participant.

Six subregions per participant.

Six subregions per participant. Includes worsening tearing, maceration, or extrusion.

Dichotomized based on the median value.

Dichotomized based on the overweight cutoff, which was similar to the median value at 1 year of 25.3 kg/m2.

Performed at the time of ACLR.

Assessed arthroscopically at the time of ACLR.

Assessed using the KT-1000 arthrometer.

TABLE 4.

Demographic and Surgical Factors Associated With Worsening Patellofemoral MRI-Detected OA Featuresa

| Cartilage Defectb |

Bone Marrow Lesionc |

Osteophyted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Prevalence of worsening, n (%) | 34/78 (44) | 14/78 (18) | 4/78 (5) | |||

| Age at time of surgerye (reference: ≤26 y) | 3.67 (1.66–8.13) | 4.19 (1.78–9.86) | 1.11 (0.37–3.29) | 0.51 (0.09–2.75) | ||

| Sex (reference: female) | 1.12 (0.54–2.34) | 3.13 (1.02–9.62) | 2.55 (0.85–7.67) | 0.17 (0.19–1.55) | 0.14 (0.01–1.72) | |

| Body mass indexf (reference: ≤25 kg/m2) | 2.03 (0.96–4.32) | 2.51 (1.19–5.27) | 1.02 (0.34–3.02) | NA | ||

| Time from injury to ACLRe (reference: ≤3 mo) | 0.56 (0.27–1.18) | 0.44 (0.21–0.94) | 0.36 (0.11–1.19) | 0.37 (0.11–1.23) | 8.39 (0.94–75.14) | 6.28 (0.76–52.84) |

| Meniscectomyg | 1.02 (0.47–2.24) | 1.45 (0.49–4.31) | 1.07 (0.20–5.74) | |||

| Cartilage defecth | 1.68 (0.85–3.31) | 1.85 (0.60–5.76) | 0.62 (0.09–4.47) | 7.37 (0.85–64.19) | 6.06 (0.70–52.49) | |

| Anteroposterior laxityi (reference: ≤3-mm between-limb difference) | 0.66 (0.30–1.47) | 0.95 (0.25–3.59) | NA | |||

Values are shown as odds ratios (95% CI). Univariate regression analysis was performed initially; participant characteristics with a P value <.20 were entered into a multivariate logistic regression generalized estimating equation model to calculate odds ratios and 95% CIs. An odds ratio >1 represents greater odds of the MRI-detected OA feature in the presence of the demographic/surgical factor. Bold values indicate a significant association (P < .05). ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available (ie, unable to perform analysis as all participants with a worsening patellofemoral osteophyte had a high body mass index); OA, osteoarthritis.

Four subregions per participant.

Four subregions per participant.

Six subregions per participant.

Dichotomized based on the median value.

Dichotomized based on the overweight cutoff, which was similar to the median value at 1 year of 25.3 kg/m2.

Performed at the time of ACLR.

Assessed arthroscopically at the time of ACLR.

Assessed using the KT-1000 arthrometer.

DISCUSSION

Worsening early OA features were evident in more than two-thirds of young patients over a 4-year period: 1 to 5 years after ACLR. Despite cartilage defects being most prevalent in the patellofemoral compartment 1 year after ACLR, the patellofemoral compartment displayed the most frequent cartilage deterioration (evident in half of the cohort). The results of this study suggest that joint features are not stable, even after surgical restoration of mechanical stability and a 12-month recovery period. Being overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) was a particularly strong determinant of deteriorating knee joint status. These worsening early OA features on MRI may reflect a progressive disease pathway that identifies those likely to suffer future radiographic OA and symptoms.

The considerable progression of existing cartilage defects (n = 24 [31%]) and the development of new defects (n = 33 [42%]), up to 5 years postoperatively, extends previous reports of worsening cartilage damage on semiquantitative scoring during the first 2 years after an ACL injury.54 Although 80% of participants in the current study had a cartilage defect 1 year after ACLR, worsening cartilage damage occurred in half of the participants over the proceeding 4 years, reflecting the rapid nature of posttraumatic OA. The rate of cartilage degeneration observedafter after ACLR (ie, approximately 13% per annum in the current study) is similar to patients with or at risk of established (ie, radiographic) OA (9%−17%)2,45 and far exceeds rates observed in uninjured older healthy knees (2% per annum).23,37 These results highlight a potential posttraumatic early OA phenotype, demonstrating the accelerated progression of pathologic joint features in young adults, compared with primary OA.17 Because early cartilage changes offer a promising window to disrupt the disease trajectory,40 these patients should be identified and the development of potential disease-modifying therapies, such as those that have shown initial promise,3,44 prioritized.

The patellofemoral joint was the knee compartment in which worsening OA features were most frequent. Although the patellofemoral joint is rarely investigated after ACLR,11 our findings add to the growing body of evidence pointing to high rates of patellofemoral degeneration. The patellofemoral compartment may be at particular risk for worsening cartilage defects and BMLs in an altered chemical environment after ACLR24 because of pre-existing or altered patellofemoral biomechanics12,33,51,60 and/or quadriceps muscle dysfunction.59 Our MRI data are consistent with quantitative MRI measures20 and second-look arthroscopic studies,55 which demonstrate rapid patellofemoral cartilage loss during the first 2 years after ACLR. We also observed greater development of radiographic patellofemoral OA than tibiofemoral OA during the 4-year observation period, more so in the ACLR knee than the contralateral knee. However, one other prospective study54 did not report higher rates of early degeneration in the patellofemoral compartment compared with the tibiofemoral compartment. Semiquantitative MRI-identified patellofemoral cartilage worsening was reported in only 3% of knees (compared with 34% tibiofemoral cartilage worsening) over the first 2 years after an ACL injury, with this lower rate potentially reflecting a lower BMI and fewer patellofemoral abnormalities at baseline.54 Nevertheless, our findings suggest that considering and managing patellofemoral joint health after ACLR are critical.

Worsening of BMLs occurred in 29% of participants, providing insight into longer-term (>2 years) posttraumatic BML behavior not previously reported.39 As our baseline was 1 year after ACLR, the majority of acute trauma-related BMLs should have resolved. Therefore, the BMLs observed may be more degenerative in nature, which was confirmed by the characteristics of the BMLs in the current study (more circumscribed, located directly subchondral, and with associated cartilage defects).42 Conversely, many BMLs in our cohort were stable (40%) or improved (40%), indicating that not all BMLs persisting at 1 year after ACLR are degenerative in nature and that resolution may require more than 1 year. In contrast to BMLs, osteophytes are more permanent and typically represent later stages of disease. This is reflected in the lower rates of worsening observed compared with other features, which is consistent with previous reports of osteophytes within the first 5 years after ACLR (8% patellofemoral and 9% tibiofemoral worsening within the immediate 2 years after the ACL injury).54 Importantly, we only considered incident osteophytes as those grade ≥2, which likely contributed to our observation of no new osteophytes over 4 years. While small osteophyte development may reflect pathological bone shape changes, and increase the risk of incident radiographic OA,35 the clinical significance of small osteophyte development requires further evaluation.

Apart from worsening meniscal lesions, which were more common in the medial (18%) than the lateral (5%) tibiofemoral compartment, worsening OA features were observed similarly in the medial and lateral tibiofemoral joint. These observations are consistent with posttraumatic radiographic OA having similar medial and lateral tibiofemoral distribution and contrast primary OA, which is typically a disease of the medial tibiofemoral joint.49 This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate longitudinal semiquantitative meniscal changes after ACLR. Despite the notion that surgical reconstruction can protect worsening meniscal abnormalities,4,31 1 in 5 demonstrated meniscal lesion worsening in the current study. Although the presence of meniscal lesions is common in noninjured asymptomatic populations aged over 50 years,15 this ACLR cohort demonstrates a much higher prevalence (80%) than age-matched patients (6%- 40%).29‘30 The observed rate (5% per annum) of meniscal lesion worsening is higher in these young adults than previous reports in noninjured older patients (1%−3% per annum) at risk of OA (age >50 years and BMI >25 kg/m2).45,46 While surgical delay > 3 months and anteroposterior knee laxity (>3-mm between-limb difference) were associated with 3 to 6 times greater odds of worsening meniscal lesions (Table 3), the clinical significance of MRI-detected meniscal lesions is uncertain.

The evaluation of baseline demographic and surgical factors revealed that being overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) was a particularly strong determinant of deteriorating knee joint status. An elevated BMI was associated with 2- to 5-fold greater odds of most OA features, irrespective of the knee compartment. This is consistent with the effect of BMI on radiographic changes.7 The longer follow-up compared with previous studies evaluating BMI in relation to MRI structural changes after ACLR may have allowed more time for BMI, in combination with probable changes in physical function and activity participation, to have an effect on joint structure. Young adults are at risk of having an increased BMI 3 to 10 years after an acute knee injury.58 Our results support this, with a significant increase in BMI from 1 (25.7 kg/m2) to 5 years (26.3 kg/m2) (P < .05). These results reinforce and strengthen the need for early OA secondary prevention interventions to address weight control through education about diet and physical activity. Each pound of lost weight leads to a 4-fold reduction in knee joint loading upon every step.34 Older age was a risk factor for worsening patellofemoral cartilage damage, reflecting degenerative changes being more prevalent in older adults.7 However, the changes that we observed were not explained entirely by age, which is evident from the higher rates of radiographic degeneration in the index knee (3.5% per annum) compared with the contralateral knee (0.25% per annum). This is supported by greater worsening of MRI-detected OA features in the current study than the normal age-related changes published previously.14–16‘23‘37‘38 Considering the high rate of new and progressive lesions after ACLR, future studies should explore other factors (ie, strength, function, alignment, and participation), which may be related to worsening of early OA features, especially given the modifiable nature of many of these factors.

A limitation of this prospective study was the loss of 33 baseline participants, resulting in a follow-up rate of 70%. Dropout was mostly caused by an inability to contact participants and relocation, reflecting a particularly young mobile population in Australia. Medial meniscal lesions were more prevalent at 1 year in those who participated in follow-up compared with those who did not. While this may have introduced some selection bias and influenced the prognosis of the current sample, there were no differences in any other baseline participant or surgical characteristics between those who did and did not attend the follow-up assessment. In addition, the current cohort appears generalizable to other large ACLR cohorts, with similar International Knee Documention Committee scores9 and return-to-sport rates5 at comparable follow-ups. Second, baseline and follow-up MRI scans were read paired and unblinded to the time point. While this approach could cause the overestimation of worsening, paired reading overcomes the limitations of the inherently crude grading system of the MOAKS.45 Future research should, however, examine the clinical implications (ie, association with symptoms) of posttraumatic MRI-detected OA features. Third, the limited number of patients with worsening of some OA features influenced the statistical stability of the regression models. Although we included worsening of all subregions and accounted for their correlation within knees with GEEs to increase statistical power, 95% CIs were relatively wide for some OA features. These need to be interpreted with caution.

Finally, we included patients with reinjuries and combined injuries to represent a typical ACLR cohort. While we acknowledge that MRI-detected OA features may have been pre-existing, a sensitivity analysis (excluding those with radiographic OA at 1 year) revealed similar rates of worsening of all MRI-detected OA features (except tibiofemoral osteophytes). Although combined injuries are associated with an increased risk of radiographic OA 10 to 15 years after an ACL injury,41,53 meniscectomy or a cartilage defect at the time of surgery did not significantly increase the risk of worsening of individual MRI-detected OA features between 1 and 5 years after ACLR. It is possible that the effect of pre-existing meniscal lesions on the joint structure may take many years to eventuate or that many more patients who have undergone ACLR would be needed to demonstrate an effect. A sensitivity analysis revealed that any MRI-detected OA feature worsening was significantly greater in those with a combined injury. These results highlight that combined injuries play a role in the worsening of MRI-detected OA features; however, our regression analysis, adjusting for other demographic factors (ie, BMI), highlights the multifactorial nature of posttraumatic early OA after ACLR. Regardless, the rate of MRI-detected OA feature worsening that we observed (ie, estimated per annum; cartilage defect, 13%; meniscal lesion, 6%; BML, 7.5%) is higher than those observed in knees of older patients with or at risk of OA (ie, estimated per annum; cartilage defect, 2%−8%; meniscal lesion, 1%−3%; BML, 3%−8%),14,16,23,37,45,48 highlighting that the ACL injury or ACLR is likely driving the considerable degeneration in these otherwise healthy young adults.

Our findings demonstrate that young adults after ACLR are at risk of worsening early MRI-detected OA features. This is important, as it is likely that worsening cartilage defects, BMLs, and meniscal lesions in young patients are not benign and may be associated with future knee OA, symptoms, or functional decline.28,46,57 Importantly, these findings are contrary to persistent beliefs among patients that ACLR will prevent OA.6,18 Considering the rapid progression of posttraumatic OA, patients should be provided with information and educated about early OA secondary prevention interventions, in particular, the potential reversibility or prevention of deterioration in structural abnormalities, symptoms, and function.40,56 Education should refer to the consequences of increased BMI, such as the increased risk of early degenerative changes that may lead to future established joint disease and symptoms.28,46

In conclusion, we observed high rates of OA-related degenerative changes on MRI in young adults between 1 and 5 years after ACLR, with two-thirds demonstrating some joint deterioration. Patellofemoral cartilage appears to be at a particularly high risk of early accelerated degeneration, especially in older and overweight patients. The concerning joint deterioration within the first 5 years after ACLR may help to identify those at greatest risk of more severe (radiographic) OA in whom secondary prevention strategies may need to be targeted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: Support for this study was provided by Arthritis Australia (Grant in Aid), La Trobe University’s Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Research Focus Area (Project Grant), the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network (Project Grant), the University of Melbourne (Research Collaboration Grant), and the University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility (Society for Mobility and Health). B.E.P. is a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) postgraduate scholarship (GNT 1114296). A.G.C.’s work was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (Neil Hamilton Fairley Clinical Fellowship; GNT 1121173). The sponsors were not involved in the design and conduct of this study; in the analysis and interpretation of the data; and in the preparation, review, or approval of the article. A.G. is the president of Boston Imaging Core Lab and a consultant to Merck Serono, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, GE Healthcare, OrthoTrophix, Sanofi, and TissueGene.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman RD, Gold GE. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;(3)(suppl A):3–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin S, LaValley MP, Guermazi A, et al. The relationship between cartilage loss on magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic progression in men and women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3152–3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson JA, Little D, Toth AP, et al. Stem cell therapies for knee cartilage repair: the current status of preclinical and clinical studies. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2253–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anstey DE, Heyworth BE, Price MD, Gill TJ. Effect of timing of ACL reconstruction in surgery and development of meniscal and chondral lesions. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(21):1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennell KL, van Ginckel A, Kean CO, et al. Patient knowledge and beliefs about knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(8):1180–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan KP. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(1):24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Church S, Keating JF. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: timing of surgery and the incidence of meniscal tears and degenerative change. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1639–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox CL, Huston LJ, Dunn WR, et al. Are articular cartilage lesions and meniscus tears predictive of IKDC, KOOS, and Marx activity level outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A 6-year multicenter cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1058–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Guermazi A, et al. Early knee osteoarthritis is evident one year following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(4):946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culvenor AG, Cook JL, Collins NJ, Crossley KM. Is patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis an under-recognised outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A narrative literature review. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(2):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Culvenor AG, Schache AG, Vicenzino B, et al. Are knee biomechanics different in those with and without patellofemoral osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(10):1566–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel DM, Malcom LL, Losse G, et al. Instrumented measurement of anterior laxity of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(5):720–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies-Tuck ML, Wluka AE, Wang Y, et al. The natural history of bone marrow lesions in community-based adults with no clinical knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):904–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding C, Jones G, Wluka AE, Cicuttini F. What can we learn about osteoarthritis by studying a healthy person against a person with early onset of disease? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22(5):520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding C, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, et al. Knee meniscal extrusion in a largely non-osteoarthritic cohort: association with greater loss of cartilage volume. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2):R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driban JB, Eaton CB, Lo GH, et al. Association of knee injuries with accelerated knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(11):1673–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feucht MJ, Cotic M, Saier T, et al. Patient expectations of primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(1):201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filbay SR, Ackerman IN, Russell TG, et al. Health-related quality of life after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1247–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frobell RB. Change in cartilage thickness, posttraumatic bone marrow lesions, and joint fluid volumes after acute ACL disruption: a two-year prospective MRI study of sixty-one subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(12):1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, et al. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:F232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grindem H, Eitzen I, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Online registration of monthly sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a reliability and validity study. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(9):748–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanna FS, Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, et al. Women have increased rates of cartilage loss and progression of cartilage defects at the knee than men: a gender study of adults without clinical knee osteoarthritis. Menopause. 2009;16(4):666–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harkey MS, Luc BA, Golightly YM, et al. Osteoarthritis-related bio-markers following anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter DJ, Conaghan PG, Peterfy CG, et al. Responsiveness, effect size, and smallest detectable difference of magnetic resonance imaging in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(suppl 1):112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Lo GH, et al. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee OA: MOAKS (MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(8):990–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunter DJ, Zhang W, Conaghan PG, et al. Responsiveness and reliability of MRI in knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of published evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(5):589–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javaid MK, Lynch JA, Tolshtykh I, et al. Pre-radiographic MRI findings are associated with onset of knee symptoms: the most study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(3):323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerosch J, Castro WH, Assheuer J. Age-related magnetic resonance imaging morphology of the menisci in asymptomatic individuals. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1996;115(3–4):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaPrade RF, Burnett QM 2nd, Veenstra MA, Hodgman CG. The prevalence of abnormal magnetic resonance imaging findings in asymptomatic knees: with correlation of magnetic resonance imaging to arthroscopic findings in symptomatic knees. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(6):739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebel B, Hulet C, Galaud B, et al. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft: a minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(7):1275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of ACL and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1756–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macri EM, Felson DT, Zhang Y, et al. Patellofemoral morphology and alignment: reference values and dose-response patterns for the relation to MRI features of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(10):1690–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee oste-oarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2026–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neogi T, Bowes MA, Niu J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based three-dimensional bone shape of the knee predicts onset of knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(8):2048–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:752–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan J, Pialat JB, Joseph T, et al. Knee cartilage T2 characteristics and evolution in relation to morphologic abnormalities detected at 3-T MR imaging: a longitudinal study of the normal control cohort from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Radiology. 2011;261(2):507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panzer S, Augat P, Atzwanger J, Hergan K. 3-T MRI assessment of osteophyte formation in patients with unilateral anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(12):1597–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papalia R, Torre G, Vasta S, et al. Bone bruises in anterior cruciate ligament injured knee and long-term outcomes: a review of the evidence. Open Access J Sports Med. 2015;6:37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollard TC, Gwilym SE, Carr AJ. The assessment of early osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Risberg MA, Oiestad BE, Gunderson T, et al. Changes in knee osteoarthritis, symptoms, and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 20-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1215–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roemer FW, Frobell R, Lohmander LS, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament OsteoArthritis Score (ACLOAS): longitudinal MRI-based whole joint assessment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(5):668–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roos EM, Arden NK. Strategies for the prevention of knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(2):92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roos EM, Dahlberg L. Positive effects of moderate exercise on glycosaminoglycan content in knee cartilage: a four-month, randomized, controlled trial in patients at risk of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3507–3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Runhaar J, Schiphof D, van Meer B, et al. How to define subregional osteoarthritis progression using semi-quantitative MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(10):1533–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma L, Nevitt M, Hochberg M, et al. Clinical significance of worsening versus stable preradiographic MRI lesions in a cohort study of persons at higher risk for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1630–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaw L, Finch CF. Trends in pediatric and adolescent anterior cruciate ligament injuries in Victoria, Australia 2005–2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(6):e599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stefanik JJ, Zhu Y, Zumwalt AC, et al. Association between patella alta and the prevalence and worsening of structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(9):1258–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sward P, Kostogiannis I, Neuman P, et al. Differences in the radiological characteristics between post-traumatic and non-traumatic knee osteoarthritis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(5):731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swirtun LR, Eriksson K, Renstrom P. Who chooses anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and why? A 2-year prospective study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(6):441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van de Velde SK, Gill TJ, DeFrate LE, et al. The effect of anterior cruciate ligament deficiency and reconstruction on the patellofemoral joint. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1150–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Ginckel A, Verdonk P, Witvrouw E. Cartilage adaptation after anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction: implications for clinical management and research? A systematic review of longitudinal MRI studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(8):1009–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Meer BL, Meuffels DE, van Eijsden WA, et al. Which determinants predict tibiofemoral and patellofemoral osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(15):975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Meer BL, Oei EH, Meuffels DE, et al. Degenerative changes in the knee 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament rupture and related risk factors: a prospective observational follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1524–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang HJ, Ao YF, Chen LX, et al. Second-look arthroscopic evaluation of the articular cartilage after primary single-bundle and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2011;124(21):3551–3555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Ding C, Wluka AE, et al. Factors affecting progression of knee cartilage defects in normal subjects over 2 years. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45(1):79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White DK, Zhang Y, Niu J, et al. Do worsening knee radiographs mean greater chances of severe functional limitation? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(10):1433–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whittaker JL, Woodhouse LJ, Nettel-Aguierre A, Emery CA. Outcomes associated with early post-traumatic osteoarthritis and other negative health consequences 3–10 years following knee joint injury in youth sport. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(7):1122–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wunschel M, Leichtle Y, Obloh C, et al. The effect of different quadriceps loading patterns on tibiofemoral joint kinematics and patellofemoral contact pressure during simulated partial weight-bearing knee flexion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(7):1099–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo JD, Papannagari R, Park SE, et al. The effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on knee joint kinematics under simulated muscle loads. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.