Abstract

Purpose

The SICCANOVE study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE) versus vehicle in patients with moderate to severe dry eye disease (DED).

Methods

In this multicenter, double-masked, parallel-group, controlled study, patients were randomized (1:1) to receive CsA CE (Ikervis®) or vehicle for 6 months. The co-primary efficacy endpoints at month 6 were mean change from baseline in corneal fluorescein staining (CFS; modified Oxford scale) and in global ocular discomfort (visual analogue scale [VAS]).

Results

The mean change in CFS from baseline to month 6 (CsA CE: n = 241; vehicle: n = 248) was significantly greater with CsA CE than with vehicle (-1.05 ± 0.98 and -0.82 ± 0.94, respectively; p = 0.009). Ocular discomfort improved similarly in both groups; however, the percentage of patients with ≥25% improvement in VAS was significantly higher with CsA CE (50.2%) than with vehicle (41.9%; p = 0.048). In a post hoc analysis of patients with severe ocular surface damage (CFS score 4) at baseline (CsA CE: n = 43; vehicle: n = 42), the percentage of patients with improvements of ≥2 grades in CFS score and ≥30% in Ocular Surface Disease Index score was significantly greater with CsA CE (p = 0.003). Treatment compliance and ocular tolerability were satisfactory and as expected for CsA use.

Conclusion

Cyclosporine A CE was well-tolerated and effectively improved signs and symptoms in patients with moderate to severe DED over 6 months, especially in patients with severe disease, who are at risk of irreversible corneal damage.

Keywords: Cationic emulsion, CsA, Cyclosporine, Dry eye disease, Severe keratitis

Introduction

Large epidemiologic studies have shown that the prevalence of dry eye disease (DED) ranges between 5% and 35% in certain populations, depending on the diagnostic criteria used (1). Dry eye disease can be initiated by numerous intrinsic (e.g., autoimmune disease) or extrinsic (e.g., dry environment) factors, with particular prominence in women and older individuals. Dry eye disease prevalence is likely to increase with the aging of the population (1–2–3–4). Quality of life is substantially reduced in patients with this debilitating disease (5). The difficulty in making an accurate and timely diagnosis and the absence of an accepted gold standard DED treatment regimen add to the societal burden associated with DED (6–7–8).

Dry eye disease is a complex, multifactorial disease resulting from a disturbance of the lacrimal functional unit and is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface (9). Tear hyperosmolarity activates a cascade of inflammatory events at the ocular surface that initiate surface epithelial damage (e.g., by apoptosis, goblet cell loss, and mucin expression alteration), and this in turn promotes tear film instability and hyperosmolarity (10–11–12–13). Patients with chronic DED become trapped in this vicious cycle of inflammation and ocular surface damage, which, if left untreated, can cause disease progression and lead to vision abnormalities and permanent damage of the corneal surface (3, 4, 14).

Patients with DED experience symptoms of discomfort, which can include eye irritation, eye pain, eye dryness, foreign body sensation, and fluctuating vision (1, 3, 4). These symptoms may correlate poorly or be discordant with clinical signs of the disease (i.e., corneal surface damage) (8, 15–16–17–18). For example, hyperalgesia can be observed in patients with early or mild DED without signs of tissue damage, whereas minimal symptoms of discomfort may be present in patients with severe DED (potentially due to downregulation of corneal sensory receptors and corneal nerve damage) (8).

Current medical strategies to relieve DED-associated symptoms rely largely on topical instillation of artificial tears or lubricating gels (19–20–21–22), which do not sufficiently address the underlying pathogenesis of DED (22) and, therefore, may not be an effective treatment in severe DED cases (23). In addition, symptom relief achieved with artificial tears or lubricating gels are largely palliative and can be relatively short-lived due to their rapid elimination via the nasolacrimal drainage system (24). More recent therapies have focused on inhibiting the important inflammatory component of DED through the introduction of topical steroid pulse therapy and anti-inflammatory agents such as cyclosporine A (CsA) in topical formulations (22, 25–26–27–28–29–30).

A 0.1% (1 mg/mL) cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE; Ikervis®, Santen SAS, Evry, France) has been developed to improve ocular delivery of CsA and enhance its immunomodulatory benefits in moderate to severe ocular inflammatory diseases, including DED (31–32–33). A previous phase II, 3-month, multicenter, double-masked clinical study in dry eye with CsA at concentrations of 0.025%, 0.05%, and 0.1% showed that 0.1% CsA CE had a comparable safety profile to the vehicle and caused an improvement in several secondary endpoints, including DED signs and symptoms, suggesting that 0.1% CsA CE should be investigated in further clinical studies (31). The objective of the current study, SICCANOVE, was to demonstrate the superiority and examine the ocular tolerance and systemic safety of 0.1% CsA CE compared with vehicle in patients with moderate to severe DED.

Methods

Study Design

This multicenter, double-masked, randomized, parallel-group, controlled study compared a sterile ophthalmic cationic emulsion of 0.1% CsA (Santen SAS) with vehicle over a 6-month treatment period. The study was conducted at 61 sites located in 6 European countries (the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom). The study design was discussed with and authorized by the Scientific Advice Working Party at the European Medicines Agency in 2006.

Subjects recruited into the study were requested to discontinue use of any topical ophthalmic treatment (including their own artificial tears), and entered a 2-week washout period during which they administered 1 drop of unpreserved artificial tears (Larmabak® 0.9% unpreserved saline solution) provided by the sponsor up to 8 times daily. During the post washout period, study-eligible patients were randomized to receive either 0.1% CsA CE or its vehicle (drug-free cationic emulsion) for up to 6 months. Because Sjögren syndrome is associated with severe, difficult-to-treat DED (34), randomization was stratified by the presence or absence of Sjögren syndrome to mitigate any imbalance between treatment arms.

During the 6-month treatment period, patients instilled 1 drop of study drug once daily in both eyes at bedtime. Administration of concomitant topical treatments was prohibited; only the use of the sponsor-supplied unpreserved artificial tears (up to 6 times daily) was permitted. Efficacy and safety were assessed at month 1 (day 28 ± 3 days), month 3 (day 84 ± 7 days), and month 6 (final visit, day 168 ± 14 days).

Participants

Patients included in this study had persistent moderate to severe DED that was refractory to conventional management (e.g., artificial tears, gels, or ointments and punctual occlusion). They were required to have had one or more symptoms of ocular discomfort (e.g., burning or stinging, foreign body sensation, itching, eye dryness, pain, blurred vision, sticky feeling, or photophobia) in at least one eye, with a severity score of ≥2 (graded on a 4-point scale). In the same eye (eligible eye), patients also had to have a tear break-up time (TBUT) of ≤8 seconds, a corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) score between 2 and 4 (scored on a modified Oxford scale), a Schirmer tear test (without anesthesia) score ≥2 mm/5 min and <10 mm/5 min, and a corneal and conjunctival lissamine green staining score ≥4 (scored with the Van Bijsterveld scale).

The main exclusion criterion for this study was a best-corrected distance visual acuity (BCDVA) score >+0.7 logMAR in eligible eyes or a history of ocular trauma, infection (viral, bacterial, fungal), or inflammation not associated with DED during the 3-month period immediately preceding the screening visit. Patients were also excluded if they had ocular surgery or ocular laser treatment within 6 months before the date of study entry in eligible eyes or within 3 months prior to study entry in noneligible eyes. Additional exclusion criteria included use of systemic or topical CsA, tacrolimus, or sirolimus within 6 months prior to study entry, or use of topical corticosteroids or prostaglandins within 1 month before study entry. Contact lens wear was not allowed during the study.

All enrolled patients provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and with the ethical principles detailed in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was registered in the EudraCT database under number 2007-000029-23 with the protocol code NVG06C103.

Efficacy assessments

Efficacy was assessed only in the worse eligible eye, defined as the eye with the highest CFS score at baseline. Two co-primary efficacy endpoints (an objective [sign] and a subjective [symptom] parameter) were assessed. The change in CFS (sign) and the change in global score of ocular discomfort unrelated to study treatment instillation (visual analogue scale [VAS], symptom) from baseline to month 6 were the primary efficacy endpoints. CFS was scored on a 7-point modified Oxford scale (0 = no staining and 7 = severe) slit-lamp examination of the cornea (35). Each symptom of ocular discomfort (i.e., burning or stinging, foreign body sensation, itching, eye dryness, pain, blurred vision, sticky feeling, and photophobia) was assessed using a VAS ranging from 0% to 100%, and the global ocular discomfort score was the mean of these 8 individual symptom scores.

Other efficacy assessments included the corneal and conjunctival lissamine green staining score graded on the Van Bijsterveld scale (at baseline and each visit) (36, 37), the Schirmer tear test without anesthesia (at baseline and month 3 and 6 visits) (9), the TBUT (at screening and each visit) (9), the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire (at baseline and each visit) (38), and the investigator's global evaluation (months 1, 3, and 6 visits). In addition, the percentage of responders in terms of ocular discomfort (patients with ≥25% improvement in VAS from baseline) and the percentage of complete responders in terms of CFS (patients with a CFS score of 0) were compared between the 2 treatment groups (Tab. I). The use of concomitant unpreserved artificial tears was also monitored at each visit over the course of the study.

TABLE I.

Responder analyses

| CsA CE, n | Vehicle, n | |

|---|---|---|

| Planned responder analyses | ||

| In patients with moderate to severe DED | 241 | 248 |

| Ocular discomfort responders = ≥25% improvement in VAS | ||

| Complete responders = CFS score of 0 | ||

| Post hoc responder analyses | ||

| In patients with CFS score ≥3 and OSDI score ≥23 at baseline | 128 | 118 |

| CFS responders = ≥2 grades improvement | ||

| OSDI responders = ≥30% improvement | ||

| Co-responders = improvement of ≥2 grades in CFS and ≥30% in OSDI | ||

| In patients with CFS score of 4 at baseline | 43 | 42 |

| CFS responders = ≥2 grades improvement | ||

| Co-responders = improvement of ≥2 grades in CFS and ≥30% in OSDI | ||

| In patients with CFS score of 2 at baseline | 83 | 93 |

| Complete responders = CFS score of 0 |

N reflects the number of patients included in the full analysis set.

CsA CE = 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion; CFS = corneal fluorescein staining; DED = dry eye disease; OSDI = ocular surface disease index; VAS = visual analogue scale.

In addition, the expression of the cell surface inflammatory marker human leukocyte antigen–DR (HLA-DR) on conjunctival epithelial cells (in arbitrary units of fluorescence [AUF] and percentage of cells) was measured by impression cytology at baseline and month 6 (39) in a subset of patients.

Safety assessments

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded throughout the study (all visits from baseline to month 6). Other safety assessments included BCDVA and intraocular pressure (IOP) at baseline and at months 3 and 6. In a subset of patients, systemic CsA levels were determined by blood sampling at the baseline and month 6 visits.

Local ocular tolerance assessments

Ocular symptoms related to study treatment instillation were assessed by asking the patient whether he or she felt some ocular discomfort at instillation of the study treatment. If the answer was “yes,” the patient described the nature of each symptom, graded its severity on a 3-point scale (mild, moderate, or severe), and indicated its duration. Slit-lamp examination was also used to assess the presence of meibomian gland obstruction, erythema or edema on the lid and conjunctiva, abnormal lashes, tear film debris, anterior chamber inflammation, and lens opacification.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on a previous phase IIa study (31). With a 2-sided t test at 5% significance level and at 80% power, a sample size of 205 patients per group was deemed necessary in order to detect a mean (±SD) difference in CFS of 0.25 ± 0.9, considered to be a clinically relevant change.

For DED symptoms, the mean change in global score of ocular discomfort (VAS) unrelated to instillation at month 6 for the vehicle group was estimated as –3.29, and an additional 25% decrease was anticipated in the active treatment group, corresponding to a total decrease of 4.11 ± 2.76. Based on these assumptions, a total sample size of 482 patients (241 per group) needed to be recruited into the study in order to achieve a significance level of 0.05 in both 2-sided tests, with an anticipated dropout rate of 15%.

Statistical Analysis

The safety population included all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug. The full analysis set (FAS) included all patients from the safety population who had at least one posttreatment efficacy evaluation. The per protocol (PP) population included patients from the FAS who did not have any major protocol deviations that could affect efficacy analysis of the co-primary endpoints. The following efficacy outcomes were analyzed for the FAS and PP datasets: change from baseline in CFS score and global score of ocular discomfort (VAS), lissamine green staining, Schirmer tear test, TBUT, OSDI, and global evaluation of efficacy by the investigator. Planned responder analyses evaluated the proportion of VAS responders (patients with ≥25% improvement in VAS) and complete responders (patients with CFS score of 0; Tab. I).

The co-primary efficacy endpoints were analyzed at month 6 using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), which included treatment, Sjögren syndrome status, and the corresponding baseline score as covariates. Missing data for the primary efficacy variables were imputed using the last observation carried forward method. Additional secondary analyses were performed to show robustness of the primary results (e.g., logistic regression and Van Elteren tests), and secondary analyses were performed at months 1 (day 28) and 3 (day 84) to detect a potential early effect of the treatment. We did not perform any multiplicity adjustments because the co-primary endpoints were expected to be simultaneously significant for the study to be considered positive.

Where appropriate, for secondary outcomes, the main ANCOVA model was fitted as described above. For parameters analyzed using repeated-measures models, the model was fitted to the change from baseline at days 28, 84, and 168 with fixed effect terms for treatments, Sjögren status, and visit, and the baseline score of the parameter as a covariate. For the exploratory HLA-DR parameter, the data were found to be log-normally distributed, and as a consequence, reporting of median values was preferred over reporting of mean values.

Post hoc analyses

Post hoc analyses were performed on 3 subsets of patients: 1) patients with a CFS score ≥3 and OSDI score ≥23 at baseline, 2) patients with a CFS score of 4 (defined as patients with severe keratitis) at baseline, and 3) patients with CFS score of 2 at baseline. Table I outlines the various responder analyses performed in these subsets of patients.

All post hoc analyses were conducted exclusively in the FAS population; a chi-square test was used to determine percentage differences between treatment groups, and ANCOVA was used for comparisons of means.

Results

Patient demographics

This study was conducted between September 2007 and September 2009. A total of 495 patients diagnosed with persistent moderate to severe DED were randomized, and 492 patients were treated with either CsA CE (242 patients) or vehicle (250 patients). A total of 82 patients withdrew from the study early (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow diagram for the SICCANOVE study. The safety population, full analysis set (FAS), and per protocol (PP) population included 492, 489, and 347 patients, respectively. AE = adverse event; CsA CE = 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion.

During the study, the overall mean compliance rates were relatively high and numerically comparable between the 2 treatment groups (96.8% in the CsA CE group and 96.9% in the vehicle group). Demographic and baseline characteristics were also comparable between the 2 treatment groups (Tab. II). The 76 male (15.5%) and 413 female (84.5%) patients included in the study had an average age of 58.2 years, and the majority of female patients were postmenopausal (294 patients [60.1%]). A total of 177 (36.2%) patients had a prior diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. As a result of the randomization and stratification process, treatment arms were balanced with respect to proportion of patients with Sjögren syndrome; there were 89 (36.9%) and 88 (35.5%) patients with Sjögren syndrome in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively.

TABLE II.

Demographics and baseline characteristics in the full analysis set

| All patients (N = 489) | CsA CE (n = 241) | Vehicle (n = 248) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.2 (12.8) | 57.6 (12.9) | 58.8 (12.7) |

| Median | 59.0 | 57.0 | 60.0 |

| Min; max | 20; 90 | 20; 90 | 21; 87 |

| Sex/menopausal status, n (%) | |||

| Female/premenopausal | 119 (24.3) | 59 (24.5) | 60 (24.2) |

| Female/postmenopausal | 294 (60.1) | 146 (60.6) | 148 (59.7) |

| Male | 76 (15.5) | 36 (14.9) | 40 (16.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 483 (98.8) | 238 (98.8) | 245 (98.8) |

| Black | 5 (1.0) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) |

| Asian | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Sjögren syndrome, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 177 (36.2) | 89 (36.9) | 88 (35.5) |

| No | 312 (63.8) | 152 (63.1) | 160 (64.5) |

| CFS score, mean (SD) | – | 2.83 (0.71) | 2.80 (0.72) |

| Lissamine green staining score, mean (SD) | – | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.7 (1.2) |

| Schirmer tear test (mm/5 min), mean (SD) | – | 4.6 (2.9) | 4.6 (2.4) |

| TBUT, s, mean (SD) | – | 3.8 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.7) |

| Global ocular discomfort score (VAS), mean (SD) | – | 47.1 (19.2)a | 43.8 (20.0)b |

| OSDI score, mean (SD) | – | 44.4 (22.0) | 42.0 (21.8) |

CsA CE = 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion; CFS = corneal fluorescein staining; OSDI = Ocular Surface Disease Index; TBUT = tear break-up time; VAS = visual analogue scale.

Assessed in 238 patients.

Assessed in 245 patients.

Efficacy results

Unless otherwise specified, all efficacy results presented here were assessed in the FAS population, and either confirmed or supported by analyses performed in the PP population.

Co-primary efficacy endpoints

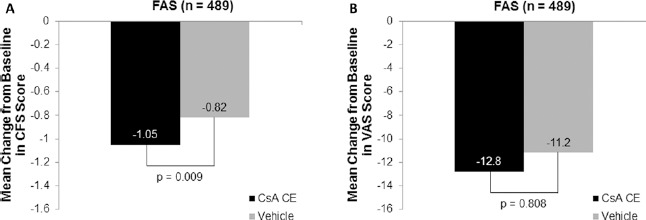

In patients with moderate to severe DED, CFS scores improved in both treatment groups between baseline and month 6; however, improvements were greater with CsA CE (-1.05 ± 0.98) than with vehicle (-0.82 ± 0.94) (Fig. 2A). The adjusted treatment difference of -0.22 (95% confidence interval [CI] -0.39, -0.06) was statistically significant (p = 0.009) in favor of the CsA CE treatment (Fig. 2A). Similar results were also seen with ordinal logistic regression (odds ratio [95% CI] 1.53 [1.11, 2.11]; p = 0.010) and a Van Elteren test (p = 0.007).

Fig. 2.

Change from baseline in the co-primary endpoints after 6 months of randomized treatment with 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE) in patients with moderate to severe dry eye disease. (A, B) Mean change from baseline in corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, respectively. A total of 241 patients and 248 patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively, were analyzed. Data represent the full analysis set (FAS) with missing data imputed by the last observation carried forward method. The statistical comparison shown reflects the results of an analysis of covariance model, which was confirmed by logistic regression and Van Elteren test.

There were noticeable improvements in the mean change in global ocular discomfort (VAS) score from baseline to month 6 in both the CsA CE (-12.82 ± 18.59) and vehicle (-11.21 ± 19.34) groups, with no significant difference between groups (difference of -0.39 [95% CI -3.5, 2.8]; p = 0.808; Fig. 2B).

Secondary efficacy endpoints

Signs

The mean change in CFS score from baseline to month 1 was significantly greater with CsA CE (-0.77) than with vehicle (-0.52; p = 0.002). Similar results favoring CsA CE (-0.92) over vehicle (-0.70; p = 0.030) were observed at month 3. These results suggest that treatment with CsA CE resulted in improved signs of moderate to severe DED after 1 month of treatment, with improvements maintained through month 3 and month 6.

Additionally, mean changes in corneal and conjunctival lissamine green staining scores were numerically (but not significantly) greater in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle at all time points: -1.5 vs -1.3 at month 1, -2.1 vs -1.7 at month 3, and -2.4 vs -2.2 at month 6. However, a statistically significant overall treatment effect (from a repeated measures model) in favor of CsA CE (p = 0.048) was observed, supporting results reported for the co-primary endpoint (CFS).

Mean changes from baseline to month 6 for Schirmer tear test (1.95 mm/5 min for CsA CE vs 1.76 mm/5 min for vehicle; p = 0.66) and TBUT (1.17 ± 1.98 seconds for CsA CE vs 1.13 ± 2.12 seconds for vehicle), though numerically higher in the CsA CE group, were not statistically different between the 2 groups.

The percentage of complete CFS responders (CFS score of 0) was numerically higher in the CsA CE group (8.3%) than in the vehicle group (5.2%) at month 6 (p = 0.17).

Symptoms

The percentage of responders (ocular discomfort unrelated to study medication [VAS]), defined as percentage improvement in VAS, showed a statistically significant difference in favor of CsA CE at month 6 (p = 0.048). The percentages of responders in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively, were 40.7% and 39.1% at month 1, 48.1% and 46.0% at month 3, and 50.2% and 42.0% at month 6. These response rates indicate that although the mean between-group difference in global VAS score (co-primary endpoint) was not statistically significant, more patients in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle group experienced a clinically relevant reduction in ocular discomfort.

Analyses of the 8 individual ocular discomfort symptoms (VAS) showed improvement of all symptoms in both treatment groups between baseline and month 6, with no statistical difference between groups, except for stinging/burning, which improved to a significantly greater extent in the vehicle group (p = 0.038). The between-group difference for the mean change in OSDI score from baseline to month 6 favored the CsA CE group (-11.8 vs -9.0 in the vehicle group), but was not statistically significant. The percentage of patients for whom treatment efficacy was classified as satisfactory or very satisfactory by investigators was slightly, but not significantly, higher in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle group at each visit: 73.8% vs 68.5% at month 1, 63.9% vs 62.5% at month 3, and 62.2% vs 59.7% at month 6.

Use of artificial tears during the study (monitored at each visit) was comparable between treatment groups.

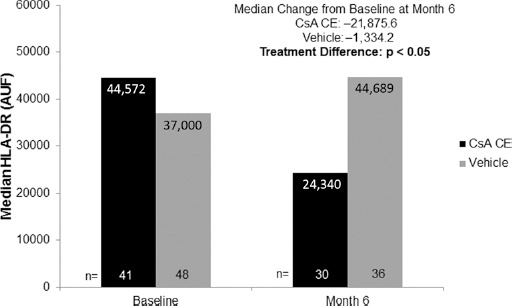

Impression cytology

Analyses of cell surface HLA-DR expression were performed in 89 patients (41 and 48 patients from the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively). At baseline, the median cell surface HLA-DR expression was comparable between treatment groups (44,572 AUF and 37,000 AUF for the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively). In patients evaluable at baseline and month 6, the median change from baseline in HLA-DR expression was -21,876 AUF and -1,334 AUF for the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively (Fig. 3), and the difference between groups was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05, post hoc analyses). This demonstrates that HLA-DR levels, indicative of conjunctival inflammation, were reduced after 6 months of treatment with CsA CE. In a separate analysis, no discernible difference was observed between the treatment groups with respect to percentage of cells expressing HLA-DR.

Fig. 3.

Human leukocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) expression at baseline and after 6 months of randomized treatment with 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE) or vehicle. As the data distribution was found to be log-normal, median values are presented for patients present at baseline (CsA CE: n = 41, vehicle: n = 48) and at month 6 (CsA CE: n = 30, vehicle: n = 36). Median changes from baseline are from patients evaluable at baseline and at month 6 in the safety population (CsA CE: n = 24, vehicle: n = 31). The statistical comparison shown reflects an analysis of covariance on the rank-transformed value, adjusted on center effect. AUF = arbitrary units of fluorescence.

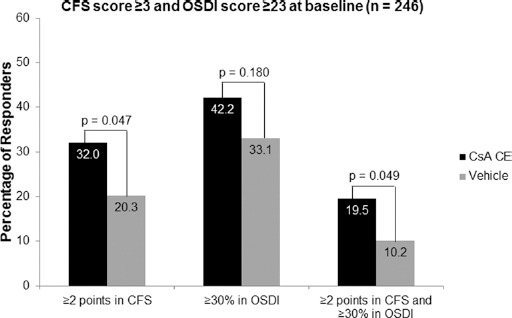

Post hoc analyses

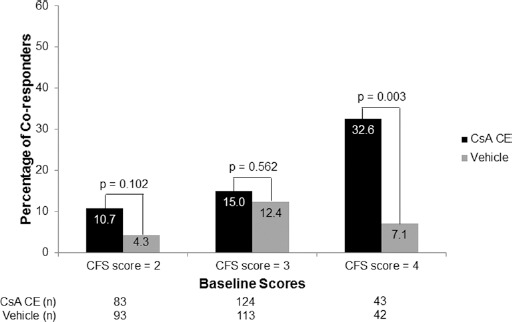

Post hoc analyses were performed on a subset of patients with CFS score ≥3 and OSDI score ≥23 at baseline. This subset represented 50% of the overall study population (n = 246), with 128 and 118 patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively. In this subpopulation, the percentage of responders in CFS, defined as patients with ≥2 grades of improvement, was statistically higher in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle group at month 6 (Fig. 4). At month 6, mean changes (SD) in CFS scores were -1.1 (0.97) in the CsA CE group and -0.77 (1.0) in the vehicle group and statistically greater with CsA CE than with vehicle (p = 0.009). The percentage of responders in OSDI (patients with ≥30% improvement in OSDI) was similar in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, but the percentage of co-responders (patients with ≥2 grades of improvement in CFS and ≥30% improvement in OSDI) in both signs and symptoms was significantly higher in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle group at month 6 (p = 0.049; Fig. 4). This co-responder analysis was also performed in patients with CFS score of 2, 3, or 4 at baseline. The percentage of co-responders was significantly higher in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle group for the patients with CFS score of 4 at baseline (Fig. 5). Patients with the highest CFS score at baseline also had a higher value of HLA-DR AUF at baseline: 48,343 (n = 41), 56,749 (n = 34), and 127,624 (n = 13) in patients with CFS scores of 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Post hoc analysis of the responder rates after 6 months of randomized treatment with 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE) or vehicle in a subset of patients with a corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) score ≥3 and an Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score ≥23 at baseline. A total of 128 patients and 118 patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively, were analyzed. Corneal fluorescein staining responders were defined as patients with ≥2 grades of improvement in CFS score. Ocular Surface Disease Index responders were defined as patients with ≥30% improvement in OSDI. Co-responders were defined as patients who met both these criteria. The statistical comparisons shown reflect the results of chi-square tests.

Fig. 5.

Post hoc analysis of the percentage of co-responders in both signs and symptoms of dry eye disease after 6 months of randomized treatment with 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE) or vehicle according to corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) scores at baseline. Data represent the full analysis set. Co-responders were defined as those having ≥2 points improvement in CFS score and ≥30% improvement in Ocular Surface Disease Index score. The statistical comparisons shown reflect the results of chi-square tests.

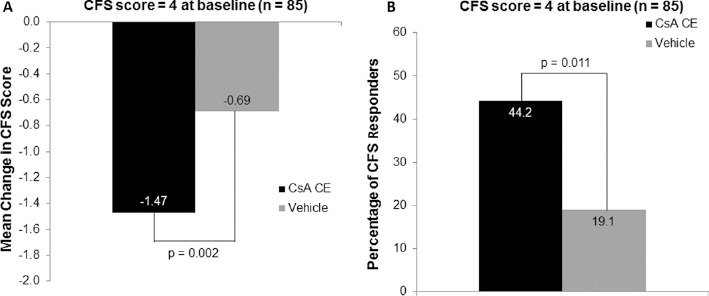

Additional post hoc analyses were performed on patients with CFS score of 4 (defined as DED patients with severe keratitis) at baseline. A total of 85 patients, with 43 and 42 patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively, presented with a CFS score of 4 at baseline. In this patient population, statistical superiority of CsA CE over vehicle was observed at month 6 for changes in CFS (p = 0.002; Fig. 6A), lissamine green staining (p = 0.003), Schirmer tear test score (p = 0.047), percentage of responders in CFS (p = 0.011; Fig. 6B), and percentage of co-responders in both signs and symptoms (p = 0.003; Fig. 5).

Fig. 6.

Post hoc analysis of the mean change in baseline in corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) score (A) and CFS responder rate (B) after 6 months of randomized treatment with 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion (CsA CE) or vehicle in a subset of patients with CFS score of 4 at baseline. A total of 43 patients and 42 patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively, were analyzed. Data represent the full analysis set. CFS responders were defined as those having ≥2 points improvement in CFS score. The statistical comparisons shown in A reflect the results of an analysis of covariance model, while those in B reflect the results of a chi-square test.

In patients with a CFS score of 2 at baseline (n = 176), a significantly greater percentage of patients in the CsA CE group exhibited complete corneal clearing (defined as a CFS score of 0) at month 6, compared with the vehicle group (p = 0.028). Of the 83 and 93 patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups with a CFS score of 2 at baseline, 21.7% and 10.8% demonstrated complete corneal clearing, respectively.

Adverse events

Ocular treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were reported in 103 (42.6%) and 67 (26.8%) patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively (Tab. III). The incidence of mild or moderate ocular TEAEs was comparable between groups (data not shown), but the incidence of severe ocular TEAEs was numerically higher in the CsA CE group (84 patients [34.7%]) than in the vehicle group (40 patients [16.0%]); however, the number of patients who withdrew due to an ocular TEAE was comparable between groups (24 patients [9.9%] in the CsA CE group and 18 patients [7.2%] in the vehicle group). The most common treatment-related TEAE in the CsA CE group was eye irritation, which was reported for 39 patients (16.1%). The number of patients reporting treatment-related ocular TEAEs was numerically higher in the CsA CE group (176 patients [78.9%]) compared with the vehicle group (66 patients [58.9%]). The only treatment-related serious ocular TEAE designated as definitely related to treatment (severe epithelial erosion of the cornea) was reported in the CsA CE group and resolved without sequelae.

TABLE III.

Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in >2% of patients (safety population)

| CsA CE (n = 242) | Vehicle (n = 250) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any ocular TEAE, n (%) | 103 (42.6) | 67 (26.8) |

| Any treatment-related ocular TEAE,a n (%) | 92 (38.0) | 41 (16.4) |

| Eye irritation | 39 (16.1) | 6 (2.4) |

| Instillation site irritation | 22 (9.1) | 4 (1.6) |

| Eye pain | 17 (7.0) | 7 (2.8) |

| Lacrimation increased | 10 (4.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Eyelid erythema | 9 (3.7) | 5 (2.0) |

| Meibomianitis | 6 (2.5) | 6 (2.4) |

| Conjunctival hyperemia | 6 (2.5) | 3 (1.2) |

| Any ocular SAE, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Any severe ocular TEAE | 84 (34.7) | 40 (16.0) |

| Any severe treatment-related ocular TEAE, n (%) | 87 (36.0) | 28 (11.2) |

| Any ocular TEAE leading to study discontinuation, n (%) | 24 (9.9) | 18 (7.2) |

CsA CE = 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion; SAE = serious adverse event; TEAE = treatment-emergent adverse event.

Treatment-related TEAEs summarized here were deemed “definitely,” “probably,” or “possibly” related by the study investigator.

Systemic TEAEs were experienced by 56 (23.1%) and 72 (28.8%) patients in the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively. The majority of systemic TEAEs were mild or moderate in intensity and were considered unrelated to the study treatment.

Systemic CsA levels were measured in 184 patients (85 and 99 from the CsA CE and vehicle groups, respectively). In the 85 patients who received CsA CE, systemic CsA levels were below the lower limit of detection (<0.050 ng/mL) in 70 patients (82.4%) and below the lower limit of quantification (0.10 ng/mL) in 11 patients (12.9%). In the remaining 4 patients (4.7%), systemic CsA levels were quantifiable but negligible: 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, and 0.2 ng/mL.

There were no changes in BCDVA or IOP over the course of the study (data not shown).

Local ocular tolerance

The percentage of patients experiencing ocular discomfort related to study treatment instillation decreased in both treatment groups between baseline (54.5% for CsA CE and 30.0% for vehicle) and month 6 (40.5% for CsA CE and 16.8% for vehicle). At month 6, few patients in both groups experienced moderate or severe ocular symptoms (CsA CE: moderate 13.2%, severe 2.9%; vehicle: moderate 2.0%, severe 0%). In addition, the majority of patients experienced mild and transient (≤15 minutes) ocular discomfort at study treatment instillation.

Discussion

The co-primary objective of this study was to demonstrate the superiority of 1 mg/mL CsA CE over vehicle in terms of effect on both a clinical sign (i.e., CFS) and a symptom (i.e., ocular discomfort) in patients with moderate to severe DED.

A significant improvement in CFS was observed with CsA CE after 6 months of treatment, and the difference between CsA CE and vehicle was statistically significant as early as after 1 month, indicating an early effect of the study drug. This result was reinforced by the results obtained in the lissamine green staining test, where the overall difference was statistically significant during the 6-month period in favor of CsA CE. Improvement in global score of ocular discomfort (assessed using VAS) was observed in both treatment groups, but this improvement was numerically greater with CsA CE. The percentage of responders as determined by ocular discomfort (patients with ≥25% decrease in VAS) was significantly greater in the CsA CE group at month 6, which represented an important, clinically relevant response.

The absence of a significant between-group difference for the global score of ocular discomfort as a co-primary endpoint could be explained by the well-documented weak correlation between signs and symptoms in DED (8, 15–16–17) and by the ability of the cationic emulsion vehicle to improve DED symptoms (36, 37). This innovative formulation increases the retention time of the nanodroplets on the ocular surface and therefore improves the drug delivery by interacting electrostatically with the negatively charged components of the tear film (31). In addition, the cationic emulsion enhances film hydration, lubrication, and stability: the aqueous medium of the emulsion droplets allows rehydration, and the oily phase replenishes the lipid layer (31, 40, 41).

Secondary study objectives, including changes in Schirmer tear test, TBUT, and OSDI score, all showed improvements numerically in favor of CsA CE, but between-treatment differences were not statistically significant. Despite this, month 6 improvements in these measures were consistently in favor of CsA CE.

Cytology impression/median cell surface AUF analysis indicated that treatment with CsA CE significantly reduced HLA-DR expression at month 6, whereas the vehicle treatment had a smaller effect. No discernible difference was observed between the treatment groups with respect to percentages of cells expressing HLA-DR. Median cell surface AUF measurement is considered to be a more reliable assessment of ocular inflammation because an individual cell's binding of a marker may vary based on the degree of inflammation present, and the inflammatory status of individual cells does not necessarily correlate with the overall number of cells expressing HLA-DR; thus, a patient with a relatively high level of inflammation may have identical results for percentages of cells expressing HLA-DR compared with another patient with lower-grade inflammation, but the same 2 individuals would be expected to have clearly distinct profiles based on median cell surface AUF. Overall, the HLA-DR results suggested that the superiority of CsA CE in reducing DED-associated conjunctival inflammation may result from the intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties previously identified for CsA (27, 29, 42–43–44–45–46–47).

In-depth analyses focused on subsets of patients with either mild DED or severe DED (i.e., both ends of the disease severity spectrum). The clinical efficacy of CsA CE over vehicle was more pronounced in the most severely affected patients, who were at risk of irreversible damage of the ocular surface and at higher risk of infection. Two groups of patients were selected: patients with a CFS score ≥3 and OSDI score ≥23 at baseline and patients with a CFS score of 4. Both groups had statistical improvements in CFS (and in lissamine green staining and Schirmer tear test for patients with a CFS score of 4) and presented a higher percentage of responders in CFS and co-responders in both signs (CFS) and symptoms (OSDI) of DED following 6-month treatment with CsA CE. Results obtained for the subgroup of patients with severe keratitis (CFS score of 4) were particularly noteworthy, as this subgroup had a high proportion of patients diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome (47%) who were unresponsive to treatment prior to participation in this study.

In this study, we also investigated the potential for patients with mild DED at baseline (i.e., with a CFS score of 2) to completely recover after 6 months of treatment with CsA CE. Indeed, the percentage of complete responders (i.e., with CFS score of 0 at month 6) was significantly greater in the CsA CE group than in the vehicle group. It is important to successfully treat the disease in its early stages, before the cycle of ocular inflammation and injury that can potentially lead to permanent and irreversible corneal damage is established (8, 14).

Cyclosporine A CE was well-tolerated in most patients, with findings consistent with the expected safety profile of CsA. There were no detrimental effects on visual acuity, IOP, or vital signs. Among the patients for whom systemic CsA levels were assessed, only 4 patients (4.7%) had quantifiable, but negligible, CsA levels (below 0.2 ng/mL).

In conclusion, once-daily instillation of CsA CE (Ikervis®) was well-tolerated and effective for the treatment of moderate to severe DED during the 6 months of the study, with significant CFS improvement observed from as early as month 1.

The data in this study were presented as posters at the following congresses: 2011 European Society of Ophthalmology meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, June 5-7, 2011; 2012 Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology meeting, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA, May 6-9, 2012; and 2012 Tear Film and Ocular Surface in Asia meeting, Kamakura, Japan, April 2-4, 2012.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scinopsis for medical writing support and Chameleon Communications International for medical copyediting support (funded by Santen, SAS); Maëva Deniaud (MD Stat Consulting) for statistical advice; and Pr. Michael Lemp, Pr. Penny Asbell, Pr. Anthony Bron, and Dr. Gary Novack for assistance with study design. This study was sponsored by Santen SAS, Evry, France.

Disclosures

Financial support: The SICCANOVE study was sponsored by Santen SAS, Evry, France.

Conflict of interest: C. Baudouin is a consultant for, or has received research grants from, Alcon, Allergan, Santen, and Théa and was an international coordinator in the SICCANOVE study. F. Figueiredo is a consultant for Santen and Théa. E. Messmer is a consultant for and has received research grants from Allergan, Dompé, and Santen and has also received research grants from Alcon, Croma Pharma, Farmigea, Oculus Optikgeräte, Théa, and Ursapharm. M. Amrane, J.S. Garrigue, and D. Ismail are employees of Santen SAS. S. Bonini is a consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Dompè, Santen, Sifi, and Sooft. A. Leonardi is a consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Santen, Sifi, and Théa. F. Figueiredo, E. Messmer, S. Bonini, and A. Leonardi were investigators in the SICCANOVE study.

References

- 1.DEWS. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaumberg DA Sullivan DA Buring JE Dana MR Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(2):318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kastelan S Tomic M Salopek-Rabatic J Novak B Diagnostic procedures and management of dry eye. BioMed Research International. 2013;2013:309723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colligris B Alkozi HA Pintor J Recent developments on dry eye disease treatment compounds. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014;28(1):19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudouin C Creuzot-Garcher C Hoang-Xuan T et al. Severe impairment of health-related quality of life in patients suffering from ocular surface diseases. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2008;31(4):369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy P Grad O Rajagopalan K The economic burden of dry eye: a conceptual framework and preliminary assessment. Cornea. 2004;23(8):751–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clegg JP Guest JF Lehman A Smith AF The annual cost of dry eye syndrome in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom among patients managed by ophthalmologists. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13(4):263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baudouin C Aragona P Van Setten G et al; ODISSEY European Consensus Group members. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(9):1168–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DEWS. Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):108–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DEWS. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baudouin C The pathology of dry eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45(Suppl 2):S211–S220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemp MA Advances in understanding and managing dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(3):350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baudouin C Aragona P Messmer EM et al. Role of hyperosmolarity in the pathogenesis and management of dry eye disease: proceedings of the OCEAN group meeting. Ocul Surf. 2013;11(4):246–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudouin C The vicious circle in dry eye syndrome: a mechanistic approach. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30:239–246.17417148 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols KK Nichols JJ Mitchell GL The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea. 2004;23(8):762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DEWS. Design and conduct of clinical trials: report of the Clinical Trials Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson ME The association between symptoms of discomfort and signs in dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2009;7(4):199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gearinger MD Mah FS Foulks GN Correlation of corneal sensitivity with subjective and objective scoring in dry eye patients. Presented at: ARVO Annual Meeting, Apr 30-May 5 2000; Fort Lauderdale, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rieger G Lipid-containing eye drops: a step closer to natural tears. Ophthalmologica. 1990;201(4):206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiffany JM Lipid-containing eye drops. Ophthalmologica. 1991;203(1):47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murube J Paterson A Murube E Classification of artificial tears. I: Composition and properties. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DEWS. Management and therapy of dry eye disease: report of the Management and Therapy Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javadi MA Feizi S Dry eye syndrome. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011;6(3):192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shell JW Ophthalmic drug delivery systems. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;29(2):117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pflugfelder SC Antiinflammatory therapy for dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(2):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aragona P Topical cyclosporine: are all indications justified? Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(8):1001–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donnenfeld E Pflugfelder SC Topical ophthalmic cyclosporine: pharmacology and clinical uses. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54(3):321–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemp MA Management of dry eye disease. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(3 Suppl):S88–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber LD Pflugfelder SC Tauber J Foulks GN Phase III safety evaluation of cyclosporine 0.1% ophthalmic emulsion administered twice daily to dry eye disease patients for up to 3 years. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(10):1790–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pflugfelder SC Maskin SL Anderson B et al. A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, multicenter comparison of loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension, 0.5%, and placebo for treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in patients with delayed tear clearance. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(3):444–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lallemand F Daull P Benita S Buggage R Garrigue JS Successfully improving ocular drug delivery using the cationic nanoemulsion, Novasorb. J Drug Deliv. 2012;2012:604204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonardi A Van Setten G Amrane M et al. Efficacy and safety of 0.1% cyclosporine A cationic emulsion in the treatment of severe dry eye disease: a multicenter randomized trial. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016;26(4):287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikervis Authorisation EMA 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002066/human_med_001851.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed October 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foulks GN Treatment of dry eye disease by the non-ophthalmologist. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34(4):987–1000x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bron AJ Evans VE Smith JA Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22(7):640–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amrane M Creuzot-Garcher C Robert PY et al. Ocular tolerability and efficacy of a cationic emulsion in patients with mild to moderate dry eye disease - a randomised comparative study. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2014;37(8):589–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savini G Prabhawasat P Kojima T Grueterich M Espana E Goto E The challenge of dry eye diagnosis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(1):31–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiffman RM Christianson MD Jacobsen G Hirsch JD Reis BL Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(5):615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh R Joseph A Umapathy T Tint NL Dua HS Impression cytology of the ocular surface. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(12):1655–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabinovich YI Vakarelski IU Brown SC Singh PK Moudgil BM Mechanical and thermodynamic properties of surfactant aggregates at the solid-liquid interface. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;270(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Royle L Matthews E Corfield A et al. Glycan structures of ocular surface mucins in man, rabbit and dog display species differences. Glycoconj J. 2008;25(8):763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nussenblatt RB Palestine AG Cyclosporine: immunology, pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986;31(3):159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baudouin C Brignole F Becquet F Pisella PJ Goguel A Flow cytometry in impression cytology specimens. A new method for evaluation of conjunctival inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(7):1458–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sall K Stevenson OD Mundorf TK Reis BL Two multicenter, randomized studies of the efficacy and safety of cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion in moderate to severe dry eye disease. CsA Phase 3 Study Group. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(4):631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brignole F Pisella PJ Goldschild M De Saint Jean M Goguel A Baudouin C Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory markers in conjunctival epithelial cells of patients with dry eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(6):1356–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brignole F Pisella PJ De Saint Jean M Goldschild M Goguel A Baudouin C Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory markers in KCS: 6-month treatment with topical cyclosporin A. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(1):90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Paiva CS Pflugfelder SC Rationale for anti-inflammatory therapy in dry eye syndrome. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008;71(6)(Suppl):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]