Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) is a proper type of refractive surgery used to remodel corneal stroma to compensate refractive errors. Corneal haze was reported as one of the side effects in several studies. This study was conducted for investigation of the effect of preventive effect of Vitamin C on eyelid edema, corneal haze, corneal epithelial healing, mitigation of pain, and epiphora.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This study has been performed as a double-blind clinical trial on 51 patients who underwent PRK surgery. The patients were randomly divided into two groups as follows: case group who received oral ascorbic acid 250 mg once daily for 7 days and control group that took placebo 3 days before and 4 days after the surgical operation. The patients underwent a surgical operation on day 0. Then, the following factors were evaluated as the main outcome: postoperative lid edema, pain, corneal haze, and corneal reepithelialization.

RESULTS:

The mean age of the patients was 28.52 ± 8.05 years. There was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of the subjective pain scores along with corneal haze and corneal reepithelialization between the treatment and placebo groups at any point during the postoperative period; however, there was a statistically significant difference and trend for lower lid edema in the ascorbic acids group on postoperative day 1 (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

This study demonstrates that ascorbic acid may provide an alternative or add-on option for lid edema relief after PRK.

Keywords: Ascorbic acid, ocular side effects, photorefractive keratectomy, Vitamin C

Introduction

Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) is the most popular refractive procedure and is being used for the treatment of various kinds of refractive errors such as myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia.[1] It is a flapless, well-established procedure with a low rate of complication which has been done for over 20 years.[2] The most important advantage of this method is the fact that a very limited, trivial thickness of the natural tissue of the cornea is affected by the surgical operation, leading to fewer side effects including postoperation pain,[3] refractive error changes after surgical operation especially in those with familial background regarding conical cornea,[4] postoperation infections resulting from contact lens usage,[5] and postoperation corneal haze;[6,7,8] however, serious complications including corneal ectasia, epithelial ingrowths, and flap-related complications have been reported.[9,10,11,12]

The corneal haziness results from inflammation response and production of toxic materials such as oxides along with a delay in epithelium healing which normally occurs during 3–4 days post-PRK operation secondary to the Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) deficiency.[3,13,14]

In addition, it seems that the main reason for postoperation pain is due to heat injuries secondary to laser excimer because the temperature of cornea sometimes reaches 53° after laser irradiation. If higher degrees of refractive errors occur, the temperature of cornea rises up, and sometimes, it reaches 60°–70°. These injuries lead to the releasing of chemical mediators including prostaglandins, histamines, and substance P.[15,16]

Postoperative pain and lid edema are PRK's main disadvantages in comparison to LASIK. A study by Mohammadi et al. demonstrated a significant association between the inflammatory signs of lid edema and post-PRK pain.[17]

Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the patients who have more severe pain are more likely to complain of ocular soreness, namely, foreign body sensation and tearing. These findings support the use of topical and systemic steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antineuralgics for the alleviation of pain.[18,19,20,21]

Vitamin C is a revitalization agent which has a significant role in the maintenance of antioxidant situation.[22] It results in the destruction of free radicals in tear film after PRK operation[23] that can prevent postoperation neovascularization.[24]

A retrospective study showed that the consumption of edible ascorbic acid supplements has a preventive effect on the development of haze after PRK.[13] However, there are no hard and fast rules regarding the dosage or duration for Vitamin C usage. Stojanovic et al. used 500 mg of Vitamin C twice a day 1 week before surgery and for 2 weeks after surgery.[13,25]

Presently, clinical pain manage measures focus on the pain medication administration. Given the potential offshoots and risks associated with pain medications,[26,27,28] we conducted the present study to investigate the preventive effect of the Vitamin C supplement on corneal haze, eyelid edema, epithelial healing, mitigation of pain, and epiphora after PRK.

Materials and Methods

This single-center, double-blind controlled trial was conducted on 102 eyes of 51 patients who underwent PRK surgery in ophthalmology clinic, Baqiyatallah hospital, Iran, as of May up to December 2015. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All aspects of the trial were approved by the Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences. Adult patients undergoing elective myopic PRK surgery were recruited. The patients were eligible to be enrolled in our trial if they had documented refraction stability of at least 1 year, had more than 18 years of age, had the ability to answer the questions posed by the researcher, had following up the treatment for 4 months or longer period after surgical operation, and had been consuming the medicines regularly. If a patient declined to continue his/her participation in the study, s/he was dismissed from the study and continued his/her treatment based on the standard criteria. Participants with myopia more than 8 D, astigmatism more than 4 D, keratometry more than 48D, corneal thickness <480 mm, and the mesopic pupil size larger than 6 mm or any degree of hyperopia were excluded from the study. Patients with keratoconus, herpes keratitis, corneal dystrophy, glaucoma, cataract, blepharitis, uveitis, pregnancy, past medical history of dry eyes, diabetes mellitus, keloid formation, autoimmune disease, and immune deficiency were not included in the study. Moreover, those who underwent previous ocular surgery were also excluded from the study. If the patients had already used soft contact lenses, they prohibited from using lenses for at least 7 days, and if they had used hard lenses, similarly, they were disallowed from using the lenses at least for 14 days before visual acuity testing. Informed consent to undergo the surgery was obtained from all the participants after discussing the possible risks of the operation.

A complete eye examination was performed including slit-lamp examination, biomicroscopy, manifest refraction, cycloplegic refraction, uncorrected visual acuity and the best-corrected visual acuity, measurement of the intraocular pressure, corneal topography, ultrasonic pachymetry, keratometry, and indirect funduscopy.

Surgical procedure

All the procedures of surgical operation were carried out by a single surgeon (AA). Before laser ablation, topical anesthesia (lidocaine 2%) was instilled in each eye. Then, an 8.5-mm epithelial defect was made using a blunt spatula following the application of a 17% alcohol solution for 15 s. After that, stromal ablation was completed by Technolas 217-p excimer laser (Technolas Perfect Vision GmbH, Munich, Germany). Subsequently, mitomycin C 0.02% (Kyowa Hakko Kogyo, Tokyo) was left on the stromal surface for 10–35 s (depending on the patient's preoperative refraction) and was rinsed with 30 ml of cold-balanced salt solution. After applying one eye drop of topical antibiotic, clobiotic 1% (Sina darou, Tehran, Iran), a therapeutic soft contact lens (Air Optix; Alcon Laboratories Inc. Fort Worth, Texas, USA) was laid over both eyes. In all participants, postoperative medications were preservative-free artificial tears every 3 h and betamethasone 0.1% eye drop (Sina darou, Tehran, Iran) four times a day for 1 month that was tapered off over 2 months. Clobiotic 1% eye drop (Sinadarou, Tehran, Iran) was prescribed every 4 h until the contact lens was removed. Once the epithelial damage healed, the betamethasone 0.1% eye drop (Sinadarou, Tehran, Iran) was replaced with a fluorometholone eye drop (Sina darou, Tehran, Iran). Refraction assessments were repeated 3 months postoperatively.

The patients were randomly divided into two groups as follows: case group who received daily one 250 mg tablet of Vitamin C and control group who took placebo (manufactured by Osveh, Iran Pharmaceutical Company) 3 days before and 4 days after the surgical operation. Both groups were recommended to avoid overusing the food containing Vitamin C. These patients were examined by an ophthalmology specialist regarding eyelid edema, epiphora, pain, and epithelial healing 1 and 4 days after the surgical operation and regarding corneal haze in the 1st and 4th month after surgical operation.

The corneal haze was phased based on the following criteria: (1) the transparent cornea with no haze; (2) slight: it does not lead to any defects in the refractive power of eye; (3) medium: it leads to defect in the refractive power of eye; (4) high: the obscurity of cornea which prevents the refraction of light; and (5) extreme: the anterior chamber was not seen.[12]

The eyelid edema was phased based on the following criteria: (1) no edema; (2) mild and tolerable: the edema is mild and tolerable; (3) medium: the eyelid is inflated; however, the patient can open his/her eyelid; and (4) severe and nontolerable: the patient is not able to open his/her eyelid actively and s/he can open it inactively.

The epiphora was phased based on the following criteria: (1) without epiphora; (2) mild epiphora so that it does not lead to interruption of the person performance; (3) medium epiphora: between the modes 2 and 3; and (4) severe: there is continuous epiphora.

The severity of epithelial defect in patient was determined accurately by slit-lamp ruler; and the improvement of epithelial defect was phased based on the following criteria: (1) total healing so that no defect remains; (2) healing so that some defect remains as points being visible by fluorescent staining; (3) improvement so that some measurable defects remain (mm2).

The patients were examined regarding the degree of pain based on numeric rating scale (NRC11) so that[15] the patients were divided into four groups as follows: 0: without any pain, 1–3: mild pain (troubling with low interference in performance of daily activity), 4–6: medium pain (significant interference in performance of daily activity), and 7–10: severe pain (unable to perform daily activity).

In the follow-up visits, at the 1st and 4th month after the procedure, visual acuity (corrected distance visual acuity and uncorrected distance visual acuity) was assessed by means of Snellen chart and then converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution scale.

Statistical analysis

After data collection, data were entered into SPSS software (version 19; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as t-test, Chi-square test, and paired sample t-test that were used for the description of central indices and dispersal and for comparing qualitative and quantitative data. In addition, nonparametric tests such as Mann–Whitney test were used for data which did not follow normal distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Twenty-five patients out of the total of 51 patients were included in the case group, and the remaining 26 patients were included in the control group. The younger individual was 20 years of age, and the eldest was 53 years of age. The average age and the gender distribution in groups are totally and separately demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study group

| Group | Treatment group (25) | Placebo group (26) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male (%) | 9 (36) | 8 (30.8) |

| Female (%) | 16 (64) | 18 (69.2) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 29.34 ( 8.97) | 27.76 ( 7.21) |

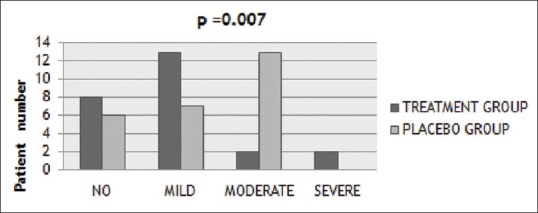

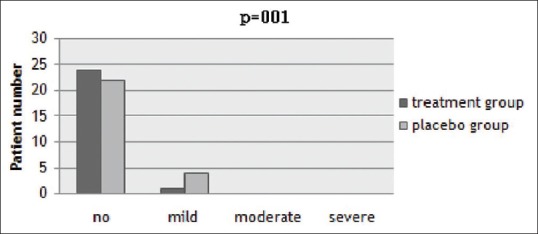

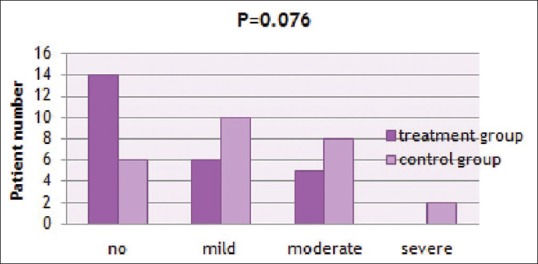

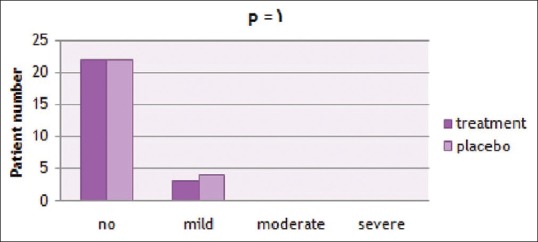

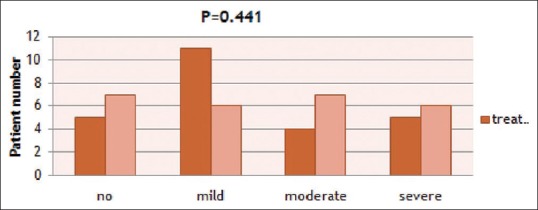

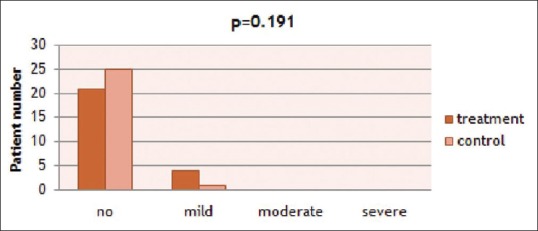

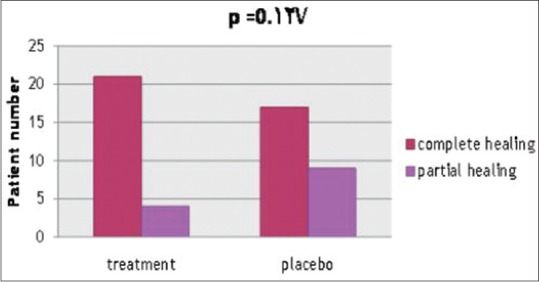

No corneal haze was shown in the investigations performed in month 1 and month 4 after the surgical operation. The eyelid edema was reduced significantly in the case group compared with the control group 1 day after the operation (P = 0.007); however, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding eyelid edema 4 days after the operation (P = 0.35). The findings of postoperation eyelid edema are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The degree of pain has no significant difference 1 day and 4 days after operation (P > 0.05). The findings of postoperation pain are shown in Figures 3 and 4. There was no significant difference regarding epiphora degree between two groups (P > 0.05). The comparisons between the degrees of epiphora on day 1 and day 4 are shown in Figures 5 and 6. The epithelial healing was so that the complete improvement in the case group (84%) was more that the control group(65%); however, it was not a statistically significant difference (P = 0.127). Figure 7 shows the comparison between the degrees of epithelial healing.

Figure 1.

Comparison of lid edema 1 day postoperation between the two groups

Figure 2.

Comparison of lid edema 4 days postoperation between the two groups

Figure 3.

Comparison of ocular pain 1 day postoperation between the two groups

Figure 4.

Comparison of ocular pain 4 days postoperation between the two groups

Figure 5.

Comparison of tearing rate 1 day postoperation between the two groups

Figure 6.

Comparison of tearing rate 4 days postoperation between the two groups

Figure 7.

Comparison of corneal healing four days postoperation between the two groups

Discussion

The major goal of this prospective, double-blind controlled trial was to investigate the effect of consumption of Vitamin C on post-PRK side effects. Our findings demonstrated that Vitamin C leads to the reduction of eyelid edema 1 day after the surgical operation; however, there was no significant difference in other variable including epiphora, epithelial healing, pain, and corneal haze.

As already known and upon investigation of the level of ascorbic acid in the human tear after PRK surgical operation, Biligihan et al.[23] found that the levels of ascorbic acid after PRK surgical operation reduced significantly. As ascorbic acid is an agent destroying free radicals in tear, treatment with local ascorbic acid may lead to the elimination of destructive effects of free radicals post-PRK surgery. In this study, the eyelid edema decreased after the surgical operation, and it can be related to the revitalizing effects of Vitamin C and its established effects on eye including the elimination of free radicals in tear after surgical operation.

Cornea haze after PRK surgical operation may result from the process of wound healing in cornea. In animal models, it was demonstrated that this process possibly begins with keratocyte apoptosis and then the overreproduction of cells. Furthermore, various studies found that omega 6, carotene, Vitamin B group, and mineral elements including copper and zinc have positive effects on surgical operation and they reduce the postoperation side effects.[21,29] Stojanovic et al.[13] demonstrated that a mixture of steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, mitomycin, and ascorbic acid reduces corneal haze. Our study cannot judge the effects of Vitamin C because the corneal haze after the surgical operation was not seen in any group.

Kasetsuwan et al.,[30] to assess the effect of local ascorbic acid on tissue damage resulting from free radical and the invasion of inflated cells in cornea after surgical operation with laser excimer, revealed that using antioxidant for reducing the tissue damage can lead to the decrease in stromal haze. Regarding the fact that ascorbic acid is effective and less harmful, it implies that it is a proper material because in our study it was displayed that the eyelid edema was reduced after the patients used oral Vitamin C along with pain reduction.

The power of this study was a double-blind, randomized prospective clinical trial; however, our research had some limitations including the limited sample size, the short-term follow-up, and the short period for the consumption of medicine; therefore, a multicenter research with a larger sample size with longer follow-up period is suggested to investigate other potential factors influencing the treatment results including job, surgery method, the type of the device, etc.

Conclusion

The results demonstrated that the prescription of oral supplement of Vitamin C decreases significantly the eyelid edema 1 day after the surgical operation in comparison with placebo.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Murakami Y, Manche EE. Prospective, randomized comparison of self-reported postoperative dry eye and visual fluctuation in LASIK and photorefractive keratectomy. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2220–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grentzelos MA, Plainis S, Astyrakakis NI, Diakonis VF, Kymionis GD, Kallinikos P, et al. Efficacy of 2 types of silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:2103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lui MM, Silas MA, Fugishima H. Complications of photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:S247–9. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20030302-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navas A, Ariza E, Haber A, Fermón S, Velázquez R, Suárez R. Bilateral keratectasia after photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg. 2007;23:941–3. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20071101-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertschinger DR, Hashemi K, Hafezi F, Majo F. Infections after PRK could have a happy ending: A series of three cases. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2010;227:315–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma S, Corbett MC, Patmore A, Heacock G, Marshall J. A comparative study of the duration and efficacy of tetracaine 1% and bupivacaine 0.75% in controlling pain following photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7:327–33. doi: 10.1177/112067219700700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedei A, Marabotti A, Giannecchini I, Ferretti C, Montagnani M, Martinucci C, et al. Photorefractive keratectomy in high myopic defects with or without intraoperative mitomycin C: 1-year results. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16:229–34. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gambato C, Ghirlando A, Moretto E, Busato F, Midena E. Mitomycin C modulation of corneal wound healing after photorefractive keratectomy in highly myopic eyes. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:208–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghadhfan F, Al-Rajhi A, Wagoner MD. Laser in situ keratomileusis versus surface ablation: Visual outcomes and complications. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:2041–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sridhar MS, Rao SK, Vajpayee RB, Aasuri MK, Hannush S, Sinha R, et al. Complications of laser-in situ-keratomileusis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2002;50:265–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melki SA, Azar DT. LASIK complications: Etiology, management, and prevention. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46:95–116. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farah SG, Azar DT, Gurdal C, Wong J. Laser in situ keratomileusis: Literature review of a developing technique. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24:989–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(98)80056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stojanovic A, Ringvold A, Nitter T. Ascorbate prophylaxis for corneal haze after photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:338–43. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20030501-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assessment, Ophthalmic Procedure Preliminary. Excimer Laser Photorefractive Keratectomy (PRK) for Myopia and Astigmatism. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishihara M, Arai T, Sato S, Morimoto Y, Obara M, Kikuchi M, et al. Temperature measurement for energy-efficient ablation by thermal radiation with a microsecond time constant from the corneal surface during ArF excimer laser ablation. Front Med Biol Eng. 2001;11:167–75. doi: 10.1163/15685570152772441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado-Codina C, Morgan PB, Efron N. Thermal consequences of photorefractive keratectomy. Cornea. 2001;20:509–15. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi SF, Z Mehrjardi H, Vakili ST, Majdi M, Mirhadi S, Rahimi F, et al. Pain and its determinants in photorefractive keratectomy. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2012;1:336–9. doi: 10.1097/APO.0b013e31826c4c5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renfro L, Snow JS. Ocular effects of topical and systemic steroids. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:505–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sher NA, Golben MR, Bond W, Trattler WB, Tauber S, Voirin TG, et al. Topical bromfenac 0.09% vs. Ketorolac 0.4% for the control of pain, photophobia, and discomfort following PRK. J Refract Surg. 2009;25:214–20. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090201-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnenfeld ED, Holland EJ, Stewart RH, Gow JA, Grillone LR, et al. Bromfenac Ophthalmic Solution 0.09% (Xibrom) Study Group. Bromfenac ophthalmic solution 0.09% (Xibrom) for postoperative ocular pain and inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1653–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nissman SA, Tractenberg RE, Babbar-Goel A, Pasternak JF. Oral gabapentin for the treatment of postoperative pain after photorefractive keratectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:623–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathleen ML. Krause's Food, Nutrition, & Diet Therapy. In: Escott-Stump S, editor. Vol. 11. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilgihan A, Bilgihan K, Toklu Y, Konuk O, Yis O, Hasanreisoğlu B, et al. Ascorbic acid levels in human tears after photorefractive keratectomy, transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy, and laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:585–8. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shakiba Y, Mostafaie A. Inhibition of corneal neovascularization with a nutrient mixture containing lysine, proline, ascorbic acid, and green tea extract. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:789–91. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nataloni R. Surface Ablation Prophylactic: Vitamin C or Mitomycin: A Benign Nutrient and a Controversial Cytostatic Share a Common Effect. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bischoff G, Brocks U. Contact lenses and keratitis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2012;229:514–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JK, Stark WJ. Anesthetic keratopathy after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:1803–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JY, Choi YS, Lee JH. Keratitis from corneal anesthetic abuse after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23:447–9. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Querques G, Russo V, Barone A, Iaculli C, Delle Noci N. [Efficacy of omega-6 essential fatty acid treatment before and after photorefractive keratectomy] J Fr Ophtalmol. 2008;31:282–6. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(08)74806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasetsuwan N, Wu FM, Hsieh F, Sanchez D, McDonnell PJ. Effect of topical ascorbic acid on free radical tissue damage and inflammatory cell influx in the cornea after excimer laser corneal surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:649–52. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]