Abstract

The entorhinal–hippocampal circuit is one of the earliest sites of cortical pathology in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Visuospatial memory paradigms that are mediated by the entorhinal–hippocampal circuit may offer a means to detect memory impairment during the early stages of AD. In this study, we developed a 4-min visuospatial memory paradigm called VisMET (Visuospatial Memory Eye-Tracking Task) that passively assesses memory using eye movements rather than explicit memory judgements. We had 296 control or memory-impaired participants view a set of images followed by a modified version of the images with either an object removed, or a new object added. Healthy controls spent significantly more time viewing these manipulations compared to subjects with mild cognitive impairment and AD. Using a logistic regression model, the amount of time that individuals viewed these manipulations could predict cognitive impairment and disease status with an out of sample area under the receiver–operator characteristic curve of 0.85. Based on these results, VisMET offers a passive, sensitive, and efficient memory paradigm capable of detecting objective memory impairment and predicting cognitive and disease status.

Pathological changes in Alzheimer's disease (AD) develop years before the onset of clinical symptoms. This period known as preclinical AD has generated considerable interest in detecting subtle memory impairments as early as possible (Albert et al. 2011; Sperling et al. 2011; Dubois et al. 2016; Mortamais et al. 2016). Memory impairment in AD has typically been established through performance on neuropsychological tasks measuring verbal recall such as the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT, Rey 1941) and the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT, Buschke 1984; Grober et al. 1987, 2000, 2010; Lemos et al. 2014; Teichmann et al. 2017). These tests have been successful in detecting memory impairment once the symptoms of AD are present (Grober et al. 2000, 2010; Ivanoiu et al. 2005; Chang et al. 2010; Landau et al. 2010; Ricci et al. 2012; Sotaniemi et al. 2012; Wolfsgruber et al. 2014). However, these conventional memory tests typically require trained personnel, a considerable amount of time to administer, and are often underused for symptomatic individuals because of the resource demands necessary to implement in clinical settings. Participants often do not like the experience of neuropsychological testing, due to the perceived poor performance on such tests. We sought to develop an easily administered, enjoyable, and sensitive paradigm for passively assessing mild memory deficits early in the disease course.

Memory tasks that are mediated by the entorhinal–hippocampal circuit, the initial site of cortical pathology in preclinical AD, offer promise for early detection. One theory suggests the entorhinal cortex represents an object's appearance and location as distinct neural representations and the hippocampus binds these representations into a single coherent representation (Eichenbaum 1999; Norman and Eacott 2005; Staresina et al. 2011; Eichenbaum et al. 2012; Knierim et al. 2014). This role for the entorhinal–hippocampal circuit has recently been supported by object and location discrimination tasks. In these paradigms, participants view a picture of an object and then following a delay, view either the same object or a lure, that is, an object with a small change in appearance or location (Reagh and Yassa 2014; Reagh et al. 2018). A change in an object's appearance and location increases activity in the anterolateral and posteromedial entorhinal cortex, respectively, while both of these changes increase activity in the hippocampus (Reagh et al. 2018).

Visuospatial memory has also been explored using eye movements as an index of memory retrieval. In these paradigms, participants view a set of images and then view manipulated (object added, removed, or moved) or repeated versions of the images (Ryan et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2006; Smith and Squire 2008). Participants spend more time viewing the manipulated regions compared to the unchanged regions in the repeated images. Medial temporal lobe damage impairs the viewing and explicit identification of these manipulations. These studies suggest that visuospatial memory paradigms are sensitive indicators of entorhinal–hippocampal function and age-associated memory decline (Yassa et al. 2011; Stark et al. 2013; Reagh et al. 2016), and therefore, may serve as an early indicator of memory impairment in AD.

The aim of the current study was to develop a passive, efficient, and sensitive paradigm that assesses visuospatial memory and evaluate its performance in healthy controls and memory-impaired subjects. Building on our previous experience with eye-tracking for assessing memory (Crutcher et al. 2009; Zola et al. 2013) and adapting a previously well studied task, we developed VisMET (Visuospatial Memory Eye-Tracking Task), which uses eye movements rather than explicit memory judgements in order to assess memory. Participants were asked to view a set of naturalistic images followed by the same set of images with either an object removed or a new object added in order to alter the visuospatial relationships between the objects and locations. The amount of time viewing these manipulations compared to unchanged parts of the images was used to measure memory of either a previously viewed object and location (removed condition), or a new object and location (added condition). We administered this 4-min paradigm to 296 control or memory-impaired subjects (mild cognitive impairment [MCI] or AD) recruited from the Emory Healthy Brain Study (EHBS) and Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC). We compared visuospatial memory performance in healthy aging and at different stages of AD and assessed whether performance could be used as a screening tool for identifying memory impairment and AD status.

Results

Visual exploration in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease during encoding

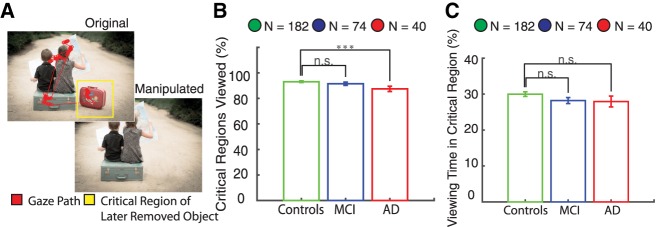

The inability to shift attentional resources may lead to inadequate viewing of the to-be manipulated item, which could confound later assessments of visuospatial memory performance. For these reasons, we first evaluated baseline attentional shifts in eye movement during image viewing to ensure that controls and memory-impaired participants all had adequate opportunity to encode the images.

The control, MCI, and AD participant groups all made at least one fixation within the critical regions containing a later removed object for nearly 90% of the images. The MCI group viewed the same percentage of critical regions as healthy controls (P > 0.05, unpaired t-test) while the AD group viewed slightly fewer critical regions than healthy controls (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test) (Fig. 1B). In the encoding phase, we also compared the average viewing time in the critical region containing a later removed object. Healthy controls spent 30% ± 0.6% of the viewing time in the critical regions, with similar amounts for MCI (28% ± 0.8%, P > 0.05, unpaired t-test) and AD (28% ± 1.5%, P > 0.05, unpaired t-test) populations (Fig. 1C). In summary, controls and memory-impaired participants viewed nearly 90% of the critical regions containing a later removed object, spending roughly 30% of the viewing time in the critical regions. These results indicate that the subject groups had similar viewing behavior with adequate opportunity to encode the majority of the images, and that any differences in visuospatial memory were unlikely due to differences in viewing behavior or attention.

Figure 1.

Visual exploration of later removed objects during the encoding phase. (A) Participants viewed images during the encoding phase containing an object that was removed in the future during the recognition phase as indicated by the yellow critical region. (B) Healthy controls, MCI, and AD participants fixated on ∼90% of the subsequently removed objects. The MCI group viewed the same percentage of critical regions as healthy controls (P > 0.05, unpaired t-test), whereas the AD group viewed slightly fewer critical regions than healthy controls (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test). (C) Healthy, MCI, and AD participants all spent roughly 30% of the time viewing the critical regions, with no significant differences across groups. (***) 0.001.

The encoding phase also included a set of images in the first presentation containing “empty” regions where items were subsequently added for the recognition phase. All three populations fixated on <5% of these empty critical regions with a viewing time of <1%. Therefore, the viewing behavior during the added condition for the groups also did not suggest any major differences that would confound later assessments of visuospatial memory.

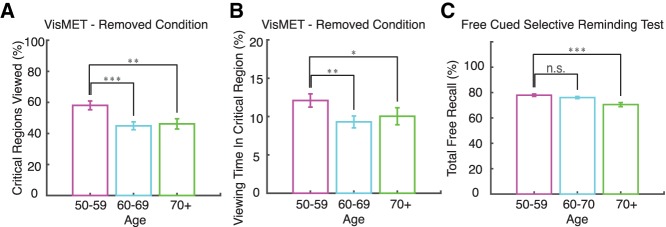

VisMET performance in healthy aging

The visuospatial memory paradigm in this study required memory for a complex set of associations between objects and locations and was assessed passively using eye movements rather than explicitly. We sought to evaluate whether visuospatial memory showed age-related declines in performance and how these differences compared to age-related declines in verbal-free recall performance. We hypothesized that healthy older participants would show impairments in discerning the manipulated objects compared to healthy younger participants. To test this hypothesis, we compared the percent viewing time and the percentage of trials with at least one fixation in the critical region across three age groups (50–59, 60–69, 70+). We compared these metrics separately for the added and removed conditions.

The group of 50- to 59-yr-old individuals performed better on the memory task than the 60–69 and 70+ age groups. The 50–59 age group fixated within 58% ± 3% of the critical regions with a removed object, whereas this percentage dropped for the older controls (45% ± 3% for the 60–69 yr olds, and 46% ± 3% for the 70+ yr olds) (Fig. 2A). These results were significant when comparing the percentage of the critical regions viewed by the 50–59 age group to the 60–69 (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test) and the 70+ age groups (P < 0.01, unpaired t-test). There was no difference in performance between the 60–69 and 70+ age groups. Similar age-related declines in memory were observed when using viewing time within critical regions as a performance metric (Fig. 2B). The 50–59, 60–69, and 70+ age groups spent 12% ± 0.9%, 9.3% ± 0.8%, and 10% ± 1% of the time viewing the critical regions with a removed object (Fig. 2B). The 50–59 age group spent significantly more time in the critical regions compared to the 60–69 (P < 0.01, unpaired t-test) and the 70+ (P < 0.05, unpaired t-test) age groups. We did not find such differences for the added condition (P > 0.05, unpaired t-test; data not shown). These results indicate that healthy adults aged 50–59 show better memory performance for the removed condition compared to healthy adults over the age of 60.

Figure 2.

Age-related changes in VisMET performance. (A) Younger participants (50–60) viewed more of the critical regions containing removed objects compared to older participants (60–70, 70+). (B) Younger participants (50–60) spent a greater percentage of viewing time in the critical regions containing the removed object compared to older participants (60–70, 70+). (C) For comparison, memory scores on the free recall portion of the FCSRT are shown. Asterisks in each panel indicate significant differences in performance as shown: (*) 0.05, (**) 0.01, (***) 0.001; unpaired t-test.

To compare these results to a commonly used neuropsychological measure of memory, we assessed age-related differences in delayed free recall performance using the FCSRT. In this population, the 50–59, 60–69, and 70+ age groups remembered 77% ± 1%, 76% ± 1%, and 70% + 1.6% of the words. The 50–59 age group did not show any significant differences in verbal-free recall compared to the 60–69 age group (P > 0.05, unpaired t-test; Fig. 2C). Rather, age-related decline in free recall performance became apparent later in the 70+ age group (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test). Collectively, these results suggest visuospatial memory performance for the removed condition provides a means to detect age-related memory decline earlier than the FCSRT.

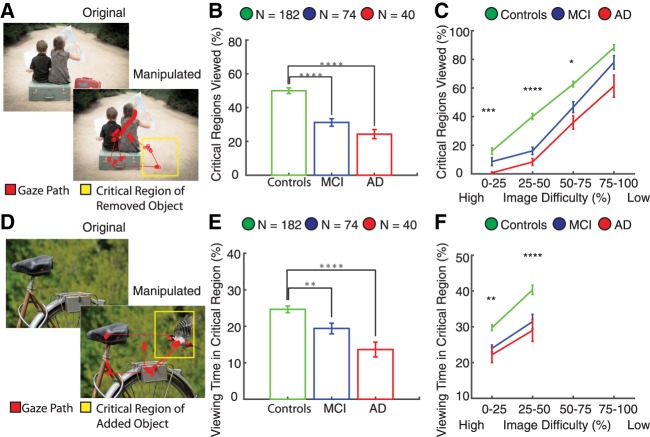

VisMET is impaired in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease

We compared visuospatial memory performance among healthy, MCI, and AD populations separately for the removed and added conditions. We first quantified viewing of the removed objects during the recognition phase (Fig. 3). The critical region for the removed objects was an empty location and as a result, the percentage of critical regions in which a visual fixation was recorded was a strong indicator that the removed object had been successfully remembered (Fig. 4A). Control participants fixated on nearly twice as many of the critical regions compared to MCI (P < 10−8, unpaired t-test) and AD (P < 10−10, unpaired t-test) populations (Fig. 4B). We also quantified viewing time within the critical regions for the removed condition. Control participants spent a significantly greater percentage of the viewing time in the critical region compared to MCI (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test) and AD populations (P < 10−4, unpaired t-test) (Supplemental Fig. S1A).

Figure 3.

Visuospatial Memory Eye-Tracking Test (VisMET). Participants were asked to view a set of images for 5 sec with a 1 sec interstimulus interval each during the encoding phase. During the recognition phase, participants viewed the same set of images with either one item removed (removed condition) or one item added (added condition). The manipulated regions used to quantify memory performance are indicated by the yellow box, which was not visible during viewing. The final test parameters consisted of the presentation of two sets of 10 original-manipulated pairs (seven with removed condition and three with added condition) with a delay of 1 min in between the original and manipulated presentations. The entire task took 4 min.

Figure 4.

VisMET performance in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Participants viewed images with either an object removed (A) or added (D) as indicated by the yellow critical regions, which was invisible to the viewer. (B) Subjects with MCI and AD showed impaired visuospatial memory performance (removed condition) compared to controls. (C) Control subjects viewed a greater percentage of the critical regions compared to AD participants regardless of the extent of difficulty between the original and manipulated presentations. The less difficult images better distinguished healthy and MCI individuals. Asterisks indicate significant differences in performance between healthy controls and MCI: (*) 0.05, (**) 0.01, (***) 0.001, (****) 0.0001; unpaired t-test). (E) Memory performance for the added condition was impaired (i.e., less time viewing the added object) in the MCI and AD populations compared to controls. (F) Manipulated images with high difficulty showed the most significant differences in performance between healthy and MCI participants as indicated by the asterisks. Viewing times for any of the added objects did not exceed 50% and as a result, difficulty could not be measured at higher viewing times.

We varied the difficulty among the manipulated images to determine if this would alter task performance (see Materials and Methods). We hypothesized that the more difficult images, operationally defined by the percentage of healthy controls with viewing behavior indicative of intact recall, to remember would best distinguish controls and memory-impaired subjects. The largest differences between control and MCI/AD participants were observed for images that were recognized as different by only 25%–50% of the control participants (P < 10−5, unpaired t-test; P < 10−8, unpaired t-test). Notably, the easiest images (operationally defined as viewing behavior indicative that they were “remembered” by 75%–100% of the participants) could only distinguish healthy controls from AD but not from MCI (P > 0.05, unpaired t-test). Thus, by controlling the difficulty of the manipulated images, we were able to create a potential method to track memory performance across varying degrees of memory impairment.

Next, we determined whether viewing of the added object in the delayed presentation was also different among healthy, MCI, and AD groups. The critical region for the added condition contained an item that was not present during the encoding phase (Fig. 4D). Control participants with intact memory spent a greater percentage of time viewing the critical region containing the added object (P < 0.01, unpaired t-test) (Fig. 4E) and viewed a greater percentage of the critical regions compared to MCI populations (P < 0.01, unpaired t-test) (Supplemental Fig. S1B). There was a similar relationship between the control and AD populations (P < 10−4, unpaired t-test; P < 10−9, unpaired t-test). We also assessed the impact of image difficulty for the added condition (see Materials and Methods). Although both bins were able to separate healthy controls from memory-impaired populations, manipulated images with 25%–50% viewing time in the critical region showed the most significant differences between the healthy controls and MCI (P < 10−4, unpaired t-test) and AD populations (P < 10−4, unpaired t-test) (Fig. 4F).

Although we expected that such differences in viewing would be due to lack of recognition of the changes in the images viewed previously, we also evaluated potential effects of eye movement-related differences in fixation accuracy across the participant groups. To control for possible differences in fixation accuracy, we quantified the average distance to the fixation cues during the first and second half of the task in visual angles. We found decreases in fixation accuracy between the first and second half of the tasks in the x direction (1.35 ± 0.05 and 1.92 ± 0.07 visual angles; unpaired t-test, <0.05) but not the y direction (1.30 ± 0.05 and 1.14 ± 0.07 visual angles; unpaired t-test, P > 0.05). Importantly, there were no differences in fixation accuracies in MCI and AD participants compared to healthy controls for the first or second half of the experiment (unpaired t-test, P > 0.05). We also did not observe any significant correlation between a participant's performance and the distance to the fixation dot (r = −0.03, P > 0.05). From these results, the variation in performance for each group is unlikely due to the changes in fixation accuracy throughout the experiment but rather, differences in memory of the removed objects when comparing the controls and memory-impaired subjects with MCI or AD.

VisMET as a screening tool for cognitive impairment and disease status

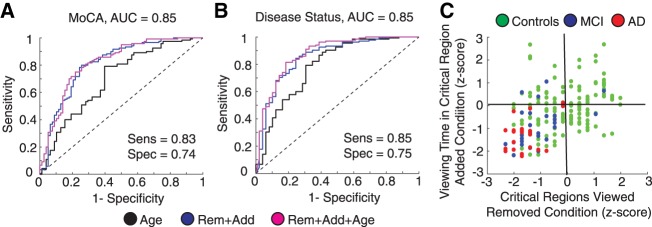

Visuospatial memory performance showed robust differences between healthy controls and memory-impaired participants. The reliability of these differences suggests that visuospatial memory performance may be used as a screening tool. To evaluate VisMET as a screening tool for cognitive impairment, we trained a logistic regression classifier using a combination of three features: viewing time in the critical regions (added), percentage of critical regions viewed (removed), and age. The output of the models predicted the likelihood of cognitive impairment as measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a widely used screening tool used to test a range of cognitive domains including memory, attention, executive function, and language. The performance of the model was assessed using the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of a leave one out cross-validation analysis.

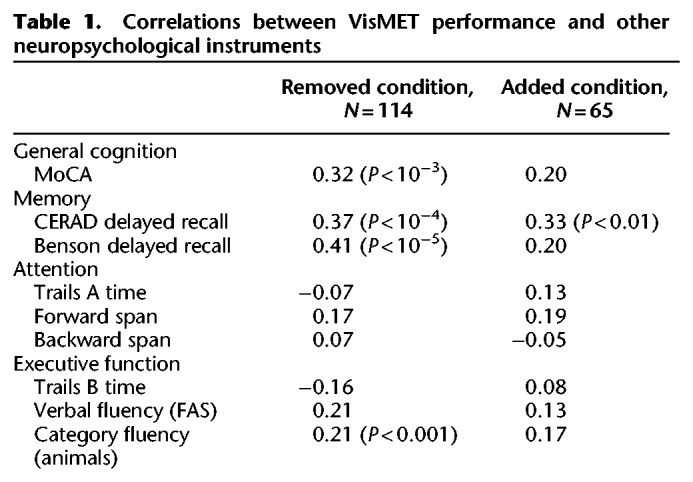

When training the models to predict cognitive impairment (MoCA ≤ 23), we found VisMET performance was able to achieve an AUC of 0.85 compared to an AUC of 0.71 and 0.56 when using age and education alone. This model was able to achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 0.83 and 0.74, respectively, using a cutoff probability of 0.64 (Fig. 5A). To further evaluate VisMET, we identified the specific cognitive domains that may be assessed by the task. We correlated visuospatial memory performance to other neuropsychological assessments given to our study population, regressing out age and education and correcting for multiple comparisons. We found robust correlations with the CERAD Word List Delayed Recall, Benson Complex Figure Delayed Recall and to a lesser extent, verbal and category fluency tests (Table 1). Based on these results, VisMET performance offers a sensitive screening method to identify cognitive impairment, particularly for the memory domain.

Figure 5.

VisMET performance predicts cognitive impairment and disease status. (A) Viewing of the removed and added objects during the recognition phase could accurately predict performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA ≤ 23 or MoCA > 23), a standard measure of cognitive impairment. (B) Viewing of the removed and added objects could separate those clinically diagnosed with MCI/AD from healthy controls. (C) Memory performance was visualized on a two-dimensional plane representing performance. Most MCI/AD participants fell within the lower left quadrant of the plane indicating below average performance for both the added and removed condition. Healthy participants within this quadrant exhibited a memory profile indicative of AD.

Table 1.

Correlations between VisMET performance and other neuropsychological instruments

We next aimed to determine the sensitivity of VisMET performance in predicting disease status. We trained a logistic regression classifier with the same three features as before, but instead the output of these models was the diagnostic classification of healthy control, MCI, or AD. Memory performance predicted MCI/AD status with an AUC of 0.85 compared to 0.73 and 0.58 when using age and education alone (Fig. 5B). Using all of the features, the model achieved a sensitivity and specificity of 0.85 and 0.75 with a cutoff probability of 0.63.

We further explored the relationship between VisMET performance and disease status. Each participant's raw performance (percentage of critical regions viewed and percentage of viewing time) was normalized using the mean and SD of healthy controls viewing the set of images. We then plotted each participant's performance on this 2D feature space (Fig. 5C). The lower left quadrant of this plane indicated below average performance for both the added and removed condition and as expected, nearly all of the MCI/AD participants were in this lower left quadrant. Interestingly, a significant portion of healthy controls’ performance fell in this same quadrant, with memory performance on VisMET similar to those with MCI and AD. Together, these results suggest that VisMET can be used as a sensitive tool for separating healthy controls from MCI/AD and to identify a population of healthy controls with an AD-like memory profile.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop an easily administered, enjoyable, and sensitive paradigm for detecting mild memory deficits, and assess its performance in a large group of healthy controls as well as a population of patients with memory impairment. To this end, 296 participants were presented with a memory paradigm in which we used eye movements to infer memory. Using eye tracking as an index of memory, we found that memory performance on the task is both age-related and different between healthy and MCI/AD participants. Performance was also dependent on the difficulty of the original and manipulated images, which allows for the task to be sensitive across a broad range of memory abilities. A multivariate model of memory performance on the task predicted cognitive impairment and AD status with high sensitivity and identified a subpopulation of healthy controls with relatively weak performance on the task.

A few studies have examined whether memory can be measured using eye movements and to determine whether memory measured using eye movements depends on the hippocampus (Ryan et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2006; Smith and Squire 2008). In these studies, participants were presented with a series of images and cued with a question about the relationships between the objects within the scene (Ryan et al. 2000). These images were followed by another set of images that were either novel, repeated, or manipulated. Participants spent more time viewing the manipulated regions only when they were unable to verbally report the manipulation had occurred. In these early studies, cueing the participants toward the manipulation could have influenced later assessments of memory. Later studies replicated this paradigm without cueing the participants toward the manipulation during the first presentation (Smith et al. 2006; Smith and Squire 2008), and found that increased viewing of the manipulated region only occurred when participants were aware of the manipulation. Moreover, the viewing time and explicit identification of the manipulation was reduced in a small group of amnestic patients with nonspecific damage to the medial temporal lobe. Although the role of cueing and delay in eye movement-based memory need to be carefully examined in future studies (Ryan and Cohen 2004; Hannula et al. 2006), these initial studies provided evidence for the use of eye movements as an indicator of memory dysfunction.

To extend these findings, we evaluated the ability of eye movements to predict memory impairment in normal aging and found an age-related decline in memory performance. Although a number of studies have shown memory decline with age (Park et al. 1996, 2002; Nilsson et al. 2004), the pattern of memory decline is unclear. Most cross-sectional aging studies measure memory decline using verbal learning paradigms and show a linear decrease in episodic memory function starting in the 20's and progressing through the rest of adult life (Hedden and Gabrieli 2004; Nyberg et al. 2012). In contrast, longitudinal studies of aging show a very different pattern, demonstrating a decline in memory performance only after the age of 60–65 (Hedden and Gabrieli 2004; Nyberg et al. 2012). A potential reason for this difference stems from the varying levels of education attainment for the different age groups in cross-sectional studies. When education is controlled in cross-sectional studies, declines in memory appear after the age of 60 (Nilsson et al. 2004). More recently, the effect of aging on memory has been investigated using mnemonic discrimination paradigms (Yassa et al. 2011; Stark et al. 2013; Reagh et al. 2016). These paradigms find an entirely different trend than previous cross-sectional studies, namely that memory begins to decline around age 20 but plateaus in the 60–90 range. We also found a similar trend with performance on our visuospatial memory task starting to plateau after 60 yr of age. To clarify the effects of aging on these different types of memory, longitudinal studies need to be conducted administering these paradigms in the same cohort of patients to allow for proper comparison.

Visuospatial memory performance was also evaluated in a group of participants with memory impairment due to AD. Memory impairment due to AD has typically been established using verbal learning tests such as the RAVLT and the FCSRT. Formal neuropsychological tests of memory are often resource intensive, requiring trained personnel and considerable amount of time to administer. Moreover, the explicit responses and awareness of performance deficits often leads to frustration or even distress for impaired subjects—sometimes to the point of discontinuing the task or declining future assessments. Even for symptomatic individuals, memory is often not assessed because of the resource demands of these tests in a clinical setting. Compared to other paradigms, memory was assessed passively using eye movements rather than instructing the participants or requiring explicit memory judgements. Using eye movements as an index of memory offers a number of practical benefits compared to explicit forms of retrieval (Pereira et al. 2014; Whitehead et al. 2015, 2018). Without the collection of explicit instructions or behavioral responses, we were able to assess memory passively in only a few minutes. Anecdotally, the paradigm appears to be strikingly less distressing and frustrating to both research participants and clinical patient populations than traditional neuropsychological tasks and also avoids issues related to task comprehension and explicit memory judgements. Conventional tasks are also subject to differences in effort, literacy, cultural variation, and decision-making capacity which can confound the measures of memory. Although the current study did not formally address the ability of this task to overcome these limitations, these potential advantages were important considerations in the development of the task and remain to be investigated.

Cognitive impairment in AD and related disorders has typically been established using cognitive screening tools such as the MoCA or MMSE. These tests often suffer from floor and ceiling effects due to their inability to change task difficulty for the specific population being tested. To address this issue, we created a means to change the difficulty of the task. In doing so, we were able to create a set of images that could potentially track the transition from MCI to AD but also ones that could track the transition from healthy to MCI. Even without adjusting the difficulty of the items, we found that visuospatial memory performance was highly sensitive for predicting cognitive impairment and disease status. The task also showed a large variation in performance among healthy controls. We speculate that healthy controls performing similarly to memory-impaired subjects may be at higher risk for AD, although this needs to be studied carefully using a longitudinal design, and with biomarkers for preclinical AD. These findings come in support of recent work suggesting that separating similar visual images rely on the same circuits affected in the preclinical stages of AD (Yassa et al. 2010a,b, 2011; Stark et al. 2013).

Our data provides further support for the use of eye movements to measure objective memory impairment. In our previous work, eye-tracking was used to assess novel object recognition memory using the visual paired comparison task (Crutcher et al. 2009; Zola et al. 2013). The amount of time viewing a novel image when placed side by side with an old image could differentiate healthy controls from memory-impaired participants. To extend these findings, we developed a task that assesses memory for the relationship between an object and its location (visuospatial memory). Compared to previous methods, we developed a method to assess memory capacity across a broad range of memory impairment, and using machine learning techniques we could predict cognitive impairment and disease status with high sensitivity. An open question remains whether memory based on eye movements can predict future memory decline earlier than standard verbal memory assessments. Based on the role of the entorhinal–hippocampal circuit in visuospatial memory, we hypothesize visuospatial memory to be an earlier predictor of entorhinal–hippocampal degeneration, as occurs in early AD, compared to current assessments and therefore predict earlier memory decline than standard memory assessments. Nonetheless, our memory paradigm based on eye movements offers a passive, sensitive, and efficient memory paradigm capable of detecting objective memory impairment and predicting disease and cognitive status.

Materials and Methods

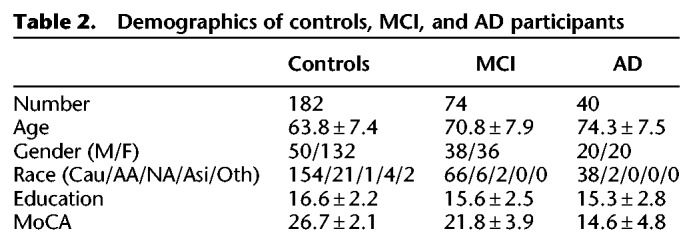

Participants

About 296 participants were recruited from research and clinical populations, including the EHBS and the ADRC (Table 2). Research participants received detailed evaluations that included neuropsychological testing and for ADRC subjects a diagnosis (healthy controls, MCI, or AD) reached after review by an interdisciplinary team of research neurologists, geriatricians, and neuropsychologists. A group of symptomatic subjects was evaluated in the Emory Memory Disorders Clinic where they received a comprehensive clinical evaluation consisting of standardized neuropsychological testing, neurological exam, brain imaging, and bloodwork, with a diagnosis by a board-certified behavioral neurologist's best clinical judgment. Controls were defined by normal memory and general cognition with preserved functional abilities. MCI was defined by impaired memory (single or multiple domain, based on cognitive testing) with preserved functional abilities, while AD was defined as impairment in two or more cognitive domains and functional abilities. The MoCA was used as a common test across the EHBS, ADRC, and clinic populations. Both age and education were significantly different between healthy controls and MCI (unpaired t-test, P < 10−5; P < 10−3) and AD populations (unpaired t-test, P < 10−10; P < 10−3) and therefore used as covariates in later analysis.

Table 2.

Demographics of controls, MCI, and AD participants

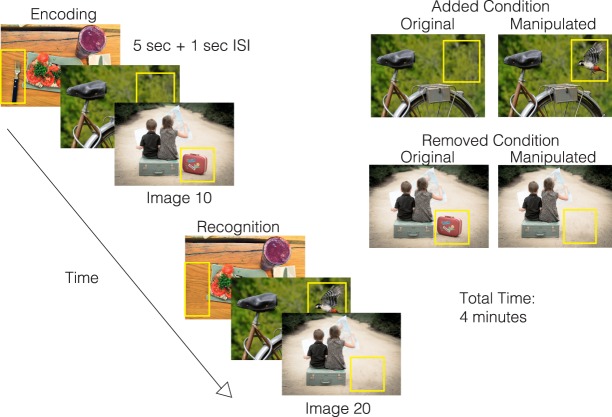

Visuospatial Memory Eye-Tracking Test (VisMET)

Participants performed a memory paradigm based on eye movements (Fig. 3). During the encoding phase, participants were simply asked to “enjoy” viewing a set of color images without any other explicit instructions (i.e., they were not informed they were being given a memory task). The images were selected for their positive aesthetic appeal. During the recognition phase, the participants viewed a modified version of the same set of images in the same order with either an item removed (“removed condition”) or an item added (“added condition”). Images were selected from an open access database of images from Pixabay and Pexel and edited by a medical illustrator using Adobe Photoshop. Images were selected to be interesting and with varying degrees of complexity.

Images were presented on a 24 inch monitor 26 inches away from the screen at a visual angle of 27 × 20 degrees. Each image was shown for 5 sec, with a white fixation cross appearing for 1 sec between images. Each set consisted of original images followed by the presentation of slightly manipulated images, that is, object added or removed. Performance was initially assessed over a range of image numbers and delay periods with minimum of 10 images and a maximum of 20 images. Presenting 10–20 images resulted in a delay of 1–2 min between the original and manipulated images. The final test parameters consisted of the presentation of two sets of 10 original-manipulated pairs (seven with removed condition and three with added condition) with a delay of 1 min in between the original and manipulated presentations. Images with 2–3 objects or focal points for the removed condition and 3–5 objects for the added condition were selected as optimal for assessing memory performance. We also only added or removed items in noncentral locations to minimize the impact of delayed eye movements from the fixation cross at the center of the calibration screen preceding each image.

Eye movement detection

The locations of an individual's focus on the screen were estimated using an EyeTribe Infrared Scanner which sampled at 30 Hz. The scanner was attached to the bottom panel of a computer screen that was mounted to the wall using an adjustable arm to allow adaptation to participants of different heights. This hardware comprises a linear array of infrared LEDs that illuminate the eye and allow for the capture of pupil and corneal reflection using a near-infrared sensitive camera. The rotation of the eye was determined by the relative positions of the corneal and pupillary reflections. At the start of each session, participants performed a nine-point calibration procedure in order to convert eye rotations into a set of gaze positions relative to the screen. A small number of participants were excluded from the analysis (8.3%) who could not calibrate to the eye tracker or did not make any attempts to view the images.

Fixation detection

For each participant, raw eye movement data were extracted using the EyeTribe Software and the data were analyzed off-line using custom scripts in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and Python. Raw gaze positions were converted into a set of fixations using a dispersion-based algorithm (Salvucci and Goldberg 2000). Each fixation was defined as a point of gaze continually remaining on the screen within 2 deg of visual angle for a period of 100 ms or more.

Measurement of visual exploration

We developed methods to quantify visual exploration for each participant by measuring the viewing of the unmanipulated object during the first presentation (Fig. 1A). To quantify viewing of unmanipulated objects during the encoding phase, we identified the location of each object to be removed or added by drawing a rectangle, defined by the x,y coordinates of its four corners, around each object. This region was identified as the “critical region” (average size: 8.8 × 7.5 visual angles). The number of fixations and the percentage of time viewing the critical region was calculated for each original image presentation. The percentage of time spent in the critical region was averaged across all original image presentations for each subject (Metric 1). We also calculated the percentage of all original image presentations with at least one fixation in the critical region for each subject (Metric 2). The calculated metrics varied depending on the specific images presented to each participant. To correct for this variation, each participant's metrics were normalized by the mean and SD of the metrics derived from the viewing behavior of the control population (# subjects > 25 for each set) viewing the same images. These metrics were compared between healthy controls and memory-impaired participants (MCI/AD) using an unpaired Student's t-test. Of note, the images for the added condition during the original presentation contained critical regions without any objects (Fig. 3). Therefore, we expected these eye movement-based metrics to be nearly zero for the added condition in the first viewing of the images.

Measurement of VisMET performance

A similar approach was used to quantify viewing of the manipulated objects during the recognition phase. A rectangular critical region was drawn outlining the location of the removed or added object. The number of fixations and the percentage of viewing time within the critical region was calculated for each manipulated image presentation. The metrics for the added and removed conditions were derived separately for each participant. For each participant, we calculated the average percentage of time spent in the critical region across all manipulated images (Metric 1). We also calculated the percentage of manipulated images with at least one fixation in the critical region for each participant, with separate measurements for the removed and added objects (Metric 2). As before, these metrics were normalized by the mean and SD of the healthy controls viewing the same image sets. These metrics of memory performance were compared across age groups and disease categories using an unpaired Student's t-test. Although both metrics were calculated for the added and removed conditions, we focused on Metric 1 for the added condition since spending at least one fixation in the critical region did not necessarily constitute successful memory. We focused on Metric 2 for the removed condition since the viewing time of many of the manipulated images was zero.

VisMET offers the option to vary the task difficulty, and as a result, track memory performance at different degrees of severity of impairment. The difficulty for remembering an image was defined based on the performance of healthy persons. The higher the percentage of healthy people that viewed the manipulated critical region, the lower the difficulty for that image. Formally, difficulty for an image containing a removed object was the percentage of healthy people that spent at least one fixation in the critical region. The difficulty for an image containing an added object was the percentage of time spent in the critical region. Images were binned into categories based on their difficulty (0%–25%, 25%–50%, 50%–75%, and 75%–100% of healthy controls showing the response) and performance was compared between healthy and memory-impaired participants for each of these bins. Of note, bins 50%–75% and 75%–100% were not analyzed for the added condition as no images had an average viewing time >50% within the critical region.

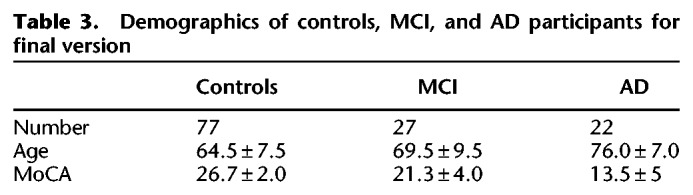

Logistic regression models

Using a leave one out cross-validation procedure, we quantified whether visuospatial memory performance on the task could be used as a screening tool for measuring cognitive impairment and predicting a diagnosis of MCI and AD. Two logistic regression classifiers were trained, each using a combination of three features: viewing time in the critical regions (added condition), percentage of critical regions viewed (removed condition), and age. The output of the models predicted the likelihood of accurately predicting performance on a standard measure of cognitive impairment (MoCA ≤ 23 or MoCA > 23) and disease status (healthy control or MCI/AD), respectively. The performance of the model was assessed using the AUC of the ROC curve. To conduct this analysis, participants needed to view images for both the added and removed condition. This analysis could only be completed with data from participants who viewed image sets that included both types of manipulations (added and removed). Thus, only the subset of participants (n = 126) that received the final version of the task were analyzed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographics of controls, MCI, and AD participants for final version

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Goizueta ADRC study team and the Emory Healthy Aging Study team for assistance with data collection. We thank Felicia Goldstein and David Loring for helpful discussions. This research was supported by funding from the Goizueta Foundation and the Goizueta Alzheimer Disease Research Center at Emory University (P50 AG025688). We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Emory Healthy Aging Study Investigators (healthyaging.emory.edu/team/researchers/).

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article is online at http://www.learnmem.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/lm.048124.118.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, et al. 2011. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 7: 270–279. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke H. 1984. Cued recall in amnesia. J Clin Neuropsychol 6: 433–440. 10.1080/01688638408401233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YL, Bondi MW, Fennema-Notestine C, McEvoy LK, Hagler DJ, Jacobson MW, Dale AM. 2010. Brain substrates of learning and retention in mild cognitive impairment diagnosis and progression to Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia 48: 1237–1247. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutcher MD, Calhoun-Haney R, Manzanares CM, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Zola SM. 2009. Eye tracking during a visual paired comparison task as a predictor of early dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 24: 258–266. 10.1177/1533317509332093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, Bakardjian H, Benali H, Bertram L, Blennow K, et al. 2016. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement 12: 292–323. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. 1999. Conscious awareness, memory and the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 2: 775–776. 10.1038/12137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Sauvage M, Fortin N, Komorowski R, Lipton P. 2012. Towards a functional organization of episodic memory in the medial temporal lobe. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36: 1597–1608. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Buschke H, Korey SR. 1987. Genuine memory deficits in dementia. Dev Neuropsychol 3: 13–36. 10.1080/87565648709540361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Lipton RB, Hall C, Crystal H. 2000. Memory impairment on free and cued selective reminding predicts dementia. Neurology 54: 827–832. 10.1212/WNL.54.4.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sanders AE, Hall C, Lipton RB. 2010. Free and cued selective reminding identifies very mild dementia in primary care. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24: 284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula DE, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. 2006. The long and the short of it: relational memory impairments in amnesia, even at short lags. J Neurosci 26: 8352–8359. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5222-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Gabrieli JDE. 2004. Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 87–96. 10.1038/nrn1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanoiu A, Adam S, Linden M, Salmon E, Juillerat AC, Mulligan R, Seron X. 2005. Memory evaluation with a new cued recall test in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol 252: 47–55. 10.1007/s00415-005-0597-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knierim JJ, Neunuebel JP, Deshmukh SS. 2014. Functional correlates of the lateral and medial entorhinal cortex: objects, path integration and local–global reference frames. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369: 20130369 10.1098/rstb.2013.0369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Jack CR, et al. 2010. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 75: 230–238. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8b8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos R, Duro D, Simões MR, Santana I. 2014. The free and cued selective reminding test distinguishes frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 29: 670–679. 10.1093/arclin/acu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortamais M, Ash JA, Harrison J, Kaye J, Kramer J, Randolph C, Pose C, Albala B, Ropacki M, Ritchie CW, et al. 2016. Detecting cognitive changes in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: a review of its feasibility. Alzheimers Dement 13: 468–492. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson LG, Adolfsson R, Bäckman L, de Frias CM, Molander B, Nyberg L. 2004. Betula: a prospective cohort study on memory, health and aging. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 11: 134–148. 10.1080/13825580490511026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norman G, Eacott MJ. 2005. Dissociable effects of lesions to the perirhinal cortex and the postrhinal cortex on memory for context and objects in rats. Behav Neurosci 119: 557–566. 10.1037/0735-7044.119.2.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg L, Lövdén M, Riklund K, Lindenberger U, Bäckman L. 2012. Memory aging and brain maintenance. Trends Cogn Sci 16: 292–305. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Smith AD, Lautenschlager G, Earles JL, Frieske D, Zwahr M, Gaines CL. 1996. Mediators of long-term memory performance across the life span. Psychol Aging 11: 621–637. 10.1037/0882-7974.11.4.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Lautenschlager G, Hedden T, Davidson NS, Smith AD, Smith PK. 2002. Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span. Psychol Aging 17: 299–320. 10.1037/0882-7974.17.2.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F, Marta LG, Marina Z, Camargo vZA, Aprahamian I, Forlenza OV. 2014. Eye movement analysis and cognitive processing: detecting indicators of conversion to Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 10: 1273–1285. 10.2147/NDT.S55371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagh ZM, Yassa MA. 2014. Object and spatial mnemonic interference differentially engage lateral and medial entorhinal cortex in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: E4264–E4273. 10.1073/pnas.1411250111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagh ZM, Ho HD, Leal SL, Noche JA, Chun A, Murray EA, Yassa MA. 2016. Greater loss of object than spatial mnemonic discrimination in aged adults. Hippocampus 26: 417–422. 10.1002/hipo.22562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagh ZM, Noche JA, Tustison NJ, Delisle D, Murray EA, Yassa MA. 2018. Functional imbalance of anterolateral entorhinal cortex and hippocampal dentate/CA3 underlies age-related object pattern separation deficits. Neuron 97: 1187–1198.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey A. 1941. L'examen Psychologique Dans Les Cas d'encephalopathie Traumatique. Arch Psychol 28: 286–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci M, Graef S, Blundo C, Miller LA. 2012. Using the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) to differentiate Alzheimer's dementia and behavioural variant fronto-temporal dementia. Clin Neuropsychol 26: 926–941. 10.1080/13854046.2012.704073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JD, Cohen NJ. 2004. Processing and short-term retention of relational information in amnesia. Neuropsychologia 42: 497–511. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J, Althoff R, Whitlow S, Cohen N. 2000. Amnesia is a deficit in relational memory. Psychol Sci 11: 454–461. 10.1111/1467-9280.00288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvucci DD, Goldberg JH. 2000. Identifying Fixations and Saccades in Eye-Tracking Protocols. In Proceedings of the 2000 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research & Applications (Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, United States, November 6–8, 2000) (pp. 71–78). New York, NY: ETRA'00. ACM. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CN, Squire LR. 2008. Experience-dependent eye movements reflect hippocampus-dependent (aware) memory. J Neurosci 28: 12825–12833. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4542-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CN, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. 2006. Experience-dependent eye movements, awareness, and hippocampus-dependent memory. J Neurosci 26: 11304–11312. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3071-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotaniemi M, Pulliainen V, Hokkanen L, Pirttilä T, Hallikainen I, Soininen H, Hänninen T. 2012. CERAD-neuropsychological battery in screening mild Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 125: 16–23. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Kaye J, Montine TJ, et al. 2011. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 7: 280–292. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina BP, Duncan KD, Davachi L. 2011. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices differentially contribute to later recollection of object- and scene-related event details. J Neurosci 31: 8739–8747. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4978-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark SM, Yassa MA, Lacy JW, Stark CEL. 2013. A task to assess behavioral pattern separation (BPS) in humans: data from healthy aging and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia 51: 2442–2449. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann M, Epelbaum S, Samri D, Levy Nogueira M, Michon A, Hampel H, Lamari F, Dubois B. 2017. Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test – accuracy for the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's and neurodegenerative diseases: a large-scale biomarker-characterized monocenter cohort study (ClinAD). Alzheimers Dement 13: 913–923. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead JC, Gambino SA, Richter JD, Ryan JD. 2015. Focus group reflections on the current and future state of cognitive assessment tools in geriatric health care. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11: 1455–1466. 10.2147/NDT.S82881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead JC, Li L, McQuiggan DA, Gambino SA, Binns MA, Ryan JD. 2018. Portable eyetracking-based assessment of memory decline. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 40: 904–916. 10.1080/13803395.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsgruber S, Jessen F, Wiese B, Stein J, Bickel H, Mösch E, Weyerer S, Werle J, Pentzek M, Fuchs A, et al. 2014. The CERAD neuropsychological assessment battery total score detects and predicts Alzheimer disease dementia with high diagnostic accuracy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 22: 1017–1028. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Stark SM, Bakker A, Albert MS, Gallagher M, Stark CE. 2010a. High-resolution structural and functional MRI of hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 51: 1242–1252. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Muftuler LT, Stark CE. 2010b. Ultrahigh-resolution microstructural diffusion tensor imaging reveals perforant path degradation in aged humans in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 12687–12691. 10.1073/pnas.1002113107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Mattfeld AT, Stark SM, Stark CEL. 2011. Age-related memory deficits linked to circuit-specific disruptions in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 8873–8878. 10.1073/pnas.1101567108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zola SM, Manzanares CM, Clopton P, Lah JJ, Levey AI. 2013. A behavioral task predicts conversion to mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 28: 179–184. 10.1177/1533317512470484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.