Abstract

Patient: Male, 67

Final Diagnosis: Recurrent metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma

Symptoms: Skin lesion

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Dermatology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Eccrine porocarcinoma, or malignant eccrine poroma, is a rare primary skin tumor that develops in the sixth and seventh decades of life, and can present as a painless and solitary nodule. Histopathology is required to confirm the diagnosis. A rare case is presented of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma, occurring four years after surgical excision of the primary scalp tumor, and includes a review of the literature.

Case Report:

A 67-year-old man initially presented with a scalp lesion that was non-painful, exophytic, and pigmented. Following complete excision, histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of eccrine porocarcinoma with clear resection margins. Four years later, he presented with discrete erythematous patches and plaques, in a zosteriform distribution, in the skin of the right neck, shoulder, and chest. A biopsy and histopathology of the skin rash confirmed metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. A positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PETCT) scan identified areas of hypermetabolic activity, with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 12, and an infiltrating soft tissue tumor in the right suboccipital region. Surgical resection of the suboccipital mass, followed by histopathology, confirmed metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. During a postoperative ear, nose, and throat (ENT) examination, he was found to have metastases in the right ear canal. The patient received five cycles of chemotherapy, but later developed renal failure and eventually chose palliative care.

Conclusions:

A rash-like presentation of skin metastasis to the trunk and metastasis to the ear from a primary eccrine porocarcinoma is rare. Early diagnosis and adequate surgical resection are recommended to reduce patient mortality.

MeSH Keywords: Eccrine Porocarcinoma; Head and Neck Neoplasms; Neoplasms, Adnexal and Skin Appendage

Background

Eccrine porocarcinoma, or malignant eccrine poroma, is a rare eccrine sweat gland tumor, comprising 0.005% of all malignant epithelial tumors [1]. This tumor was first described in 1963 by Pinkus and Mehregan and was termed, epidermotropic eccrine carcinoma. In 1969, Mishima and Morioka suggested the term, eccrine porocarcinoma [2]. Eccrine porocarcinoma usually presents in the sixth and seventh decades of life and typically affects the lower and upper extremities, scalp, face, ear, eyelids, vulva, penis, pubis, and abdomen [3,4]. The prevalence of eccrine porocarcinoma is the same in men and women.

The eccrine glands of the skin contain an intraepidermal spiral duct, the acrosyringium. Both eccrine poroma and eccrine porocarcinoma arise from an intraepithelial portion of the eccrine sweat gland. Eccrine porocarcinoma can also develop from malignant transformation of benign eccrine poroma and has been reported to arise from the benign hamartoma known as sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn (SNJ) [5]. Eccrine porocarcinoma may also develop in former sites of irradiation, lymphedema, and trauma, and has been associated with Hodgkin’s disease, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), pernicious anemia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, sarcoidosis, extramammary Paget’s disease, and xeroderma pigmentosum [5].

A rare case is presented of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma, occurring four years after surgical excision of the primary scalp tumor, and includes a review of the literature.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man, with a previous medical history of depression and hypothyroidism, was initially admitted to hospital for evaluation of a scalp skin lesion that had increased in size over a four-month period (Figure 1). The scalp lesion measured 3×2 cm, and was exophytic and pigmented, immobile, and irregular in appearance, but was not painful. General examination showed no abnormal findings of the respiratory, cardiac, and neurological systems and no abnormal findings were found in the abdomen. No palpable lymphadenopathy was found on examination of the neck.

Figure 1.

The macroscopic appearance of an exophytic, pigmented, immobile, irregular lesion on the scalp in a case of eccrine porocarcinoma.

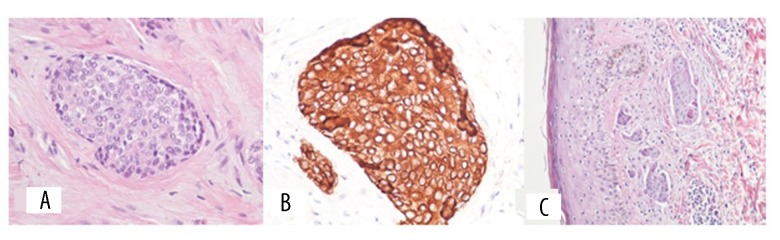

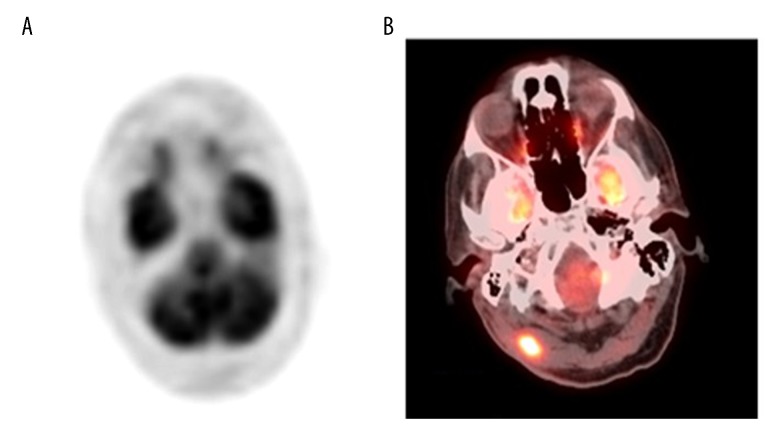

The scalp lesion was completely excised, and histology confirmed that the resection margins were negative for malignancy. Histopathology showed a tumor with large pleomorphic round and oval cells arranged in groups and lobules that infiltrated the dermal tissue, and tumor cells within dilated lymphatics in the dermis. Immunohistochemistry showed positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, including CK8/18, CK 34B12 and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and negative immunostaining for prostate specific antigen (PSA) and prostate specific acid phosphatase (PSAP). The histopathology and immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine porocarcinoma of the scalp (Figures 2A–2C). Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) performed at the time showed no uptake in the scalp, neck, or the rest of the body (Figure 3A). The patient was initially followed-up by the oncology department.

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs of the histopathology and immunohistochemistry of the scalp tumor showing features consistent with a diagnosis of eccrine porocarcinoma. (A) Photomicrograph of the histopathology shows large, pleomorphic, round and oval cells, arranged in groups and lobules, infiltrating the dermal tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). (B) Photomicrograph of the immunohistochemistry (brown) shows malignant cells that are strongly positive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3). (C) Photomicrograph of the histopathology shows tumor nests in the dermis. Malignant cells are also seen within dilated lymphatics. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography (PET) images of the patient on initial presentation and following recurrence of an eccrine porocarcinoma four years later. (A) Positron emission tomography (PET) scan, performed at initial presentation, shows no uptake in the brain or skull. (B) PET scan performed four years later shows hypermetabolic activity in an infiltrative soft tissue mass in the right posterior sub-occipital region.

Four years later, the patient was admitted to hospital again for evaluation of a skin rash that was confluent and had discrete erythematous patches and plaques in a zosteriform distribution on the right side of the neck, right shoulder, and right chest (Figure 4). Biopsy of the rash showed a metastatic carcinoma involving the lymphatics, consistent with a diagnosis of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. A repeat PET-CT scan showed hypermetabolic activity infiltrating a soft tissue mass in the right sub-occipital region, with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 12 (Figure 3B). He underwent complete excision of the right suboccipital mass, which measured 0.5×0.4×0.3 cm by 1.9×0.7×0.7 cm. On histopathology, the diagnosis was consistent with metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma, and the deep lateral margins and medial margins were negative for the tumor. He also underwent radical neck dissection and a right cervical lymph node biopsy. The histopathology was consistent with metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. The cell morphology on of the tumor cells was similar to those in the initial scalp lesion.

Figure 4.

The macroscopic appearance of the right side of the neck, right shoulder, and right chest shows multiple confluent and discrete erythematous patches and plaques.

During a postoperative ear, nose, and throat (ENT) examination, which included otoscopic ear examination, he was found to have metastases in the right ear canal. He had not complained of ear pain, discharge, or impaired hearing. Because this was a cancer recurrence, the patient completed five cycles of chemotherapy with docetaxel and carboplatin. Chemotherapy was discontinued when the patient developed renal failure. He was offered palliative therapy and radiation therapy for his declining physical condition. The patient chose palliative care and died a few months later.

Discussion

Eccrine porocarcinoma, or malignant eccrine poroma, is a rare primary malignant adnexal tumor of the skin with unknown etiology [6]. Adnexal tumors can arise from one of the four primary adnexal structures of the skin, the hair follicle, sebaceous, eccrine, and apocrine glands. Eccrine poroma and porocarcinoma arise from eccrine sweat glands.

Eccrine porocarcinoma belongs to a group of malignant eccrine and apocrine tumors that also include mucinous carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, digital papillary adenocarcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and extramammary Paget’s disease, which are slow-growing malignant tumors that can metastasize. Eccrine porocarcinoma can metastasize to local lymph nodes or distant organs, and cutaneous metastases may be found near the primary tumor. Other less common sites for metastasis include the bone, bladder, breast, retroperitoneum, ovaries, liver, and lungs [7].

In the skin, eccrine porocarcinoma presents as an asymptomatic, painless, solitary nodule that can ulcerate, and may cause pain. The tumor can present as a red, dome-shaped skin nodule with a shiny surface, or as a wart-like plaque. Because eccrine porocarcinoma is rare, it can be misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, amelanotic melanoma, seborrheic keratosis, Bowen’s disease, fibroma, verruca vulgaris, or metastatic adenocarcinoma [8,9]. Therefore, all rapidly growing skin lesions should be biopsied for histopathology to confirm the diagnosis.

Histologically, eccrine porocarcinoma is characterized by a nuclear atypia, an infiltrative growth pattern, increased mitotic activity, and necrosis, with varied growth patterns and metaplastic changes that include squamous cell, clear cell, and mucous cell metaplasia, spindle cell differentiation, and lymphovascular invasion [8].

There is no single immunohistochemical marker for eccrine cells, but a diagnostic panel can include keratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CD117, S100 protein, smooth muscle actin (SMA), p63, calponin, cytokeratin 14, and B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) [10,11]. Immunohistochemical markers can be used to identify the cell of origin of intraepidermal malignant tumors, CK19 can be used to distinguish between eccrine porocarcinoma and Bowen’s disease, and positive immunostaining for CK5/8 and CK7 with negative CK10 staining can be used to distinguish between Paget’s disease and eccrine porocarcinoma [12]. The expression of P16 protein and loss of expression of the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein have been reported to be diagnostic features of eccrine porocarcinoma [13]. Benign and malignant tumors can be differentiated by expression of Ki-67 and p53 mutation [14].

Eccrine porocarcinoma should be diagnosed and treated early to prevent malignancy. Tumor ulceration can lead to secondary infection, while incomplete removal may lead to recurrence. For local disease, surgical resection is the main treatment and may include a wide local excision with negative surgical margins, or Mohs micrographic surgery [15,16]. Radiation therapy has not been shown to confer any survival benefit over surgery alone but may be an option if the surgical margins cannot be cleared, or the patient cannot undergo surgery [17]. In cases of poorly differentiated eccrine porocarcinoma, lymph node involvement has been reported in 50% of cases, and for tumors with poor prognostic features, sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended [18,19].

There is no adequate chemotherapy or drug treatment for eccrine porocarcinoma. Partial or minimal response to chemotherapy with cisplatin, bleomycin, methotrexate, adriamycin, isotretinoin, and interferon-alpha have been reported, and some benefit has been shown for treatment with docetaxel [7]. In the case reported, following discussion with the oncologists, he was treated with docetaxel and carboplatin. He received five cycles of chemotherapy, but showed no response, and treatment ceased when he developed renal failure. The patient initially presented with a scalp lesion, and following complete excision, he was in remission for four years. He later presented with a skin rash and suboccipital lesion, and both biopsies were consistent with metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma. Incidentally, on otoscopic ear examination, cancer metastases were seen in the right ear canal. Metastatic involvement of the skin and ear makes this a rare case of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma.

Conclusions

Eccrine porocarcinoma, or malignant eccrine poroma, is a rare skin malignancy that is typically seen in the elderly population. The rash-like presentation of metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma on the trunk is unique, and metastatic satellite lesions in ear canal also make it rare. Treating eccrine porocarcinoma can be challenging, but early identification and resection can decrease mortality.

Footnotes

Institution where work was done

Bronx Care Health System, Affiliated with Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Wick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT, 3rd, Su WP. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. I. Eccrine carcinomas. Cancer. 1985;56(5):1147–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<1147::aid-cncr2820560532>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaz Salgado MA, García CG, Lopez Martin JA, et al. Porocarcinoma: Clinical evolution. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(2):264–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown CW, Jr, Dy LC. Eccrine porocarcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):433–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berke A, Grant-Kels JM. Eccrine sweat gland disorders: Part I. Neoplasms. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33(2):79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: A review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignantforms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1053–61. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms. Part 1: An approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129–44. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bree E, Volalakis E, Tsetis D, et al. Treatment of advanced malignant eccrine poroma with locoregional chemotherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(5):1051–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): A clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710–20. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klenzner T, Arapakis I, Kayser G. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the ear mimicking basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:158–60. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obaidat NA, Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. An approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):145–59. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto K, Takai T, Fukumoto T, et al. CD117 (KIT) is a useful immunohistochemical marker for differentiating porocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43(3):219–26. doi: 10.1111/cup.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aslan F, Demirkesen C, Cağatay P, Tüzüner N. Expression of cytokeratin sub-types in intraepidermal malignancies: A guide for differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(8):531–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu LH, Ichiki Y, Kitajima Y. Aberrant expression of p16 and RB protein in eccrine porocarcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29(8):473–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC. Malignant adnexal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(Suppl. 2):S93–126. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ad Hoc Task Force. Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: A report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):531–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lloyd MS, El-Muttardi N, Robson A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2003;11(3):153–56. doi: 10.1177/229255030301100304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avraham JB, Villines D, Maker VK, et al. Survival after resection of cutaneous adnexal carcinomas with eccrine differentiation: Risk factors and trends in outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108(1):57–62. doi: 10.1002/jso.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swanson JD, Jr, Pazdur R, Sykes E. Metastatic sweat gland carcinoma: Response to 5-fluorouracil infusion. J Surg Oncol. 1989;42(1):69–72. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: A case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):e188–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]