Abstract

Elysia chlorotica, a sacoglossan sea slug found off the East Coast of the United States, is well-known for its ability to sequester chloroplasts from its algal prey and survive by photosynthesis for up to 12 months in the absence of food supply. Here we present a draft genome assembly of E. chlorotica that was generated using a hybrid assembly strategy with Illumina short reads and PacBio long reads. The genome assembly comprised 9,989 scaffolds, with a total length of 557 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 442 kb. BUSCO assessment indicated that 93.3% of the expected metazoan genes were completely present in the genome assembly. Annotation of the E. chlorotica genome assembly identified 176 Mb (32.6%) of repetitive sequences and a total of 24,980 protein-coding genes. We anticipate that the annotated draft genome assembly of the E. chlorotica sea slug will promote the investigation of sacoglossan genetics, evolution, and particularly, the genetic signatures accounting for the long-term functioning of algal chloroplasts in an animal.

Subject terms: Genome, DNA sequencing, Marine biology, Genomics, Evolution

Background & Summary

Many species of sacoglossan sea slugs are able to intracellularly sequester chloroplasts from their algal food, a phenomenon known as kleptoplasty, that is not observed in other clades of animals. In some sacoglossan species, the captured chloroplasts (usually called kleptoplasts) are maintained and capable of photosynthesis for one to several months, earning these molluscs the title of “solar-powered sea slugs”1–3. Among them, Elysia chlorotica, where the kleptoplasts are obtained from the filamentous alga Vaucheria litorea, is particularly interesting because it can retain functional chloroplasts in the cells of its digestive diverticula and survive without food supply for ten months to one year2,3. The mechanism that keeps ‘stolen’ chloroplasts functioning requires special proteins produced by nuclear genes of the algal host4. While there is a great deal of evidence using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)5–10, western blot11,12, RNA-seq13, and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) investigations14 that algal nuclear genes are present in the sea slug, genomic resources are scarce for E. chlorotica, limited to a mitochondrial genome assembly7, a few transcriptomes13,15,16 and a low-coverage genome sequencing dataset of eggs17. There are no nuclear genome assemblies, even fragmented ones, publicly available for E. chlorotica so far. From an evolutionary perspective, although Mollusca represents the second largest animal phylum with around 85,000 extant species18, a fairly limited number of mollusc genomes have been sequenced yet19–31, with only 23 genomes publicly available on NCBI genome database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse/#!/overview/mollusca; access on December 5, 2018). Particularly, no reference genome has been generated for any sacoglossan mollusc.

In this study, we present the first draft genome assembly for the representative solar-powered sea slug E. chlorotica, which was assembled from Illumina short and PacBio long reads using a hybrid and hierarchical assembly strategy. We anticipate that this well-annotated draft genome assembly and the massive sequencing data generated in this study will serve as substantial resources for future studies of the evolution of sacoglossan molluscs, and particularly, for the investigation of the genetic basis underlying the long-term maintenance of algal chloroplasts in these sea slugs.

Methods

Sample collection, library construction and sequencing

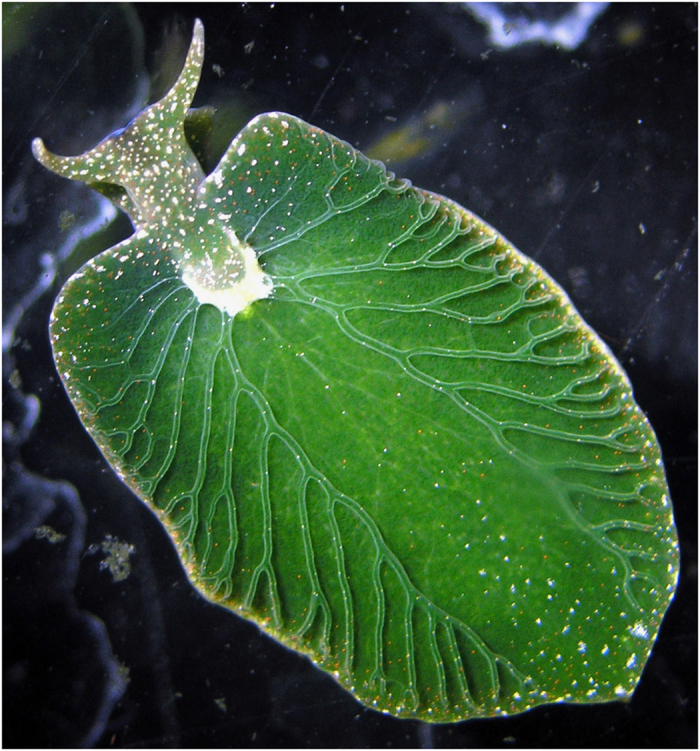

Specimens of the sea slug E. chlorotica (NCBI taxonomy ID 188477; Fig. 1) were collected from a salt marsh near Menemsha on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts in 2010. From there, the animals were shipped to Tampa, Florida, for maintenance in aquaria containing sterile, artificial seawater (1000 mosm; Instant Ocean, VA, USA) on a 14:10 light–dark cycle at 10 °C as described in Pierce et al. (2012)13.

Figure 1. A photograph of an adult Elysia chlorotica (image courtesy of Patrick Krug).

In Tampa, total DNA, including slug genomic, mitochondrial and algal chloroplast DNA, was extracted from a whole adult specimen that had been starved for at least 2 months using a Nucleon Phytopure DNA extraction kit (GE Healthcare UK limited, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The same kit was used to extract total DNA, including slug genomic and mitochondrial DNA, from a batch of ~1000 larvae that had not hatched from the egg capsules and never been fed. The larvae do not have any chloroplasts. A total of 11 Illumina DNA paired-end (PE) libraries were constructed according to the standard protocol provided by Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA), including six libraries with short-insert sizes (170 bp × 2, 500 bp × 2, and 800 bp × 2) from the adult DNA, and five mate-paired libraries with long-insert sizes (2.5 kb × 2, 5 kb × 2, 10 kb × 1) from the larval DNA. Sequencing was performed for all the 11 libraries on the HiSeq 2000 platform according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), using the modes of PE100 for all the short-insert libraries and PE49 + PE90 for each of the five mate-paired libraries. A total of 296.73 Gb of Illumina reads were produced (Data Citation 1 and Data Citation 2), which can cover the estimated haploid genome size of E. chlorotica by k-mer analysis for 516 times (Table 1).

Table 1. Statistics of DNA reads produced for the E. chlorotica genome in this study.

| Platform | Insert size (bp) | No. of Libraries | Read length (bp) | Raw data |

Clean data |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bases (Gb) | Sequencing coverage (X) | Physical coverage (X) | Total bases (Gb) | Sequencing coverage (X) | Physical coverage (X) | |||||||||||

| Note: Each of the five Illumina mate-pair libraries (2.5 kb × 2, 5 kb × 2 and 10 kb × 1) was run on two lanes with read length of 49 bp and 90 bp, respectively. Coverage calculation was based on the estimated genome size of 575 Mb according to k-mer analysis. Sequence coverage is the average number of times a base is read, while physical coverage is the average number of times a base is spanned by sequenced fragments. | ||||||||||||||||

| Illumina | 170 | 2 | 100 | 35.55 | 61.83 | 52.55 | 28.67 | 49.86 | 41.56 | |||||||

| 500 | 2 | 100 | 32.44 | 56.42 | 141.06 | 18.12 | 31.51 | 84.04 | ||||||||

| 800 | 2 | 100 | 34.51 | 60.02 | 240.04 | 21.01 | 36.54 | 158.32 | ||||||||

| 2,500 | 2 | 49;90 | 76.60 | 133.22 | 1,752.62 | 43.77 | 76.12 | 1,301.05 | ||||||||

| 5,000 | 2 | 49;90 | 83.67 | 145.51 | 4,771.57 | 46.30 | 80.52 | 2,767.88 | ||||||||

| 10,000 | 1 | 49;90 | 33.97 | 59.08 | 3,841.34 | 18.45 | 32.09 | 2,174.84 | ||||||||

| Total | 11 | — | 296.73 | 516.05 | 10,799.18 | 176.32 | 306.64 | 6,527.68 | ||||||||

| PacBio | 6,000 | 3 | 1,224 | 9.45 | 16.43 | — | 5.36 | 9.32 | — | |||||||

In addition, 9.45 Gb (16X) PacBio long-reads with a mean subread length of 1.2 kb and N50 subread length of 1.7 kb were sequenced for another DNA sample (Data Citation 1 and Data Citation 2), which was extracted from another starved adult specimen, that had been shipped frozen to Okazaki, using the CTAB method32 and purified with DNeasy Plant mini kit (Qiagen). Three libraries were constructed according to the 6 kb library construction protocol and sequenced in 93 SMRT cells on the PacBio RS platform using the C2 chemistry following the manufacturer’s instructions (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA).

Estimation of genome size and heterozygosity

Prior to downstream analyses, all the Illumina reads were submitted to strict quality control using SOAPnuke (v1.5.3)33. Duplicated reads arising from PCR amplification during library construction, adapter-contaminated reads and low-quality reads were removed using parameters -l 7 -q 0.4 -n 0.02 -d -t 10,0,10,0 for the short-insert (i.e. 170 bp, 500 bp and 800 bp) data and -l 7 -q 0.35 -n 0.05 -d -S for the long-insert (i.e. 2.5 kb, 5 kb and 10 kb) data, yielding a total of 176.32 Gb of clean Illumina reads (Table 1).

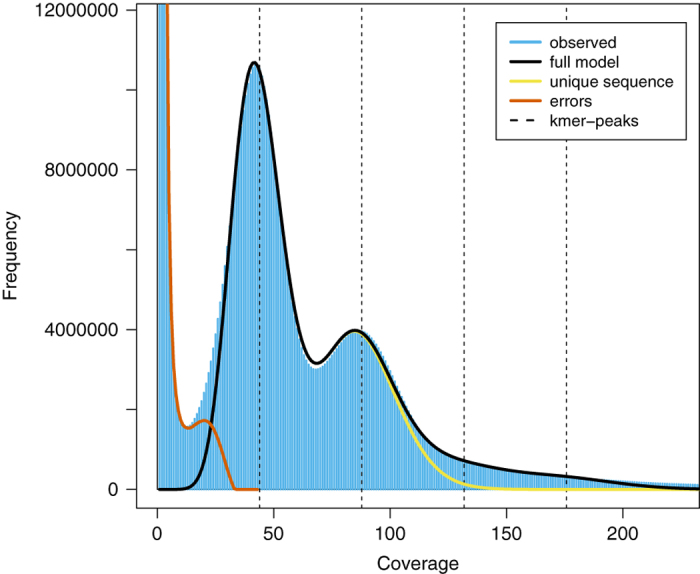

All of the clean reads from the six short-insert libraries, except those derived from algal chloroplasts, slug mitochondria and the previously reported endogenous retrovirus of E. chlorotica34, were used to estimate the size and heterozygosity of the E. chlorotica nuclear genome by k-mer analysis. Reads were considered to be derived from organelles or retrovirus if a pair of reads was mapped to any of the three genomes (Data Citation 3, 4, 5) by BWA-MEM (v0.7.16)35, and such read pairs were discarded, resulting in a total of 62.8 Gb Illumina data for k-mer analysis. The haploid genome size of E. chlorotica was estimated to be around 575 Mb according to k-mer frequency distributions generated by Jellyfish (v2.2.6)36 using a series of k values (17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29 and 31) with the -C setting, which was calculated as the number of effective k-mers (i.e. total k-mers – erroneous k-mers) divided by the homozygous peak depth (Table 2). But this estimated haploid genome size might be an underestimate, as certain parts of the E. chlorotica genome (e.g. GC-extreme regions) may have failed to be sequenced due to technical limitations37, and/or repetitive sequences may not have been resolved properly by k-mer analysis given that mollusc genomes are generally known to be repeat rich19–31.

Table 2. Estimation of genome size and heterozygosity of E. chlorotica by k-mer analysis.

| k | Total number of k-mers | Minimum coverage (X) | Number of erroneous k-mers | Homozygous peak | Estimated genome size (Mb) | Estimated heterozygosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: k-mer frequency distributions were generated by Jellyfish (v2.2.6) using 62.8 Gb Illumina clean data as input and a series of k values (17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29 and 31) with the -C setting. Minimum coverage was the coverage depth value of the first trough in k-mer frequency distribution. k-mers with coverage depth less than the minimum coverage were regarded as erroneous k-mers. Estimated genome size was calculated as (Total number of k-mers – Number of erroneous k-mers)/Homozygous peak. | ||||||

| 17 | 51,187,863,592 | 13 | 1,410,585,877 | 86 | 579 | 3.59 |

| 19 | 49,735,232,800 | 11 | 1,804,614,643 | 84 | 571 | 3.93 |

| 21 | 48,282,601,880 | 11 | 2,010,206,114 | 80 | 578 | 3.90 |

| 23 | 46,829,970,960 | 11 | 2,152,586,758 | 78 | 573 | 3.79 |

| 25 | 45,377,340,040 | 10 | 2,235,304,391 | 75 | 575 | 3.69 |

| 27 | 43,924,709,120 | 10 | 2,327,591,479 | 72 | 578 | 3.57 |

| 29 | 42,472,078,200 | 9 | 2,370,847,012 | 70 | 573 | 3.47 |

| 31 | 41,019,447,280 | 9 | 2,433,307,151 | 67 | 576 | 3.36 |

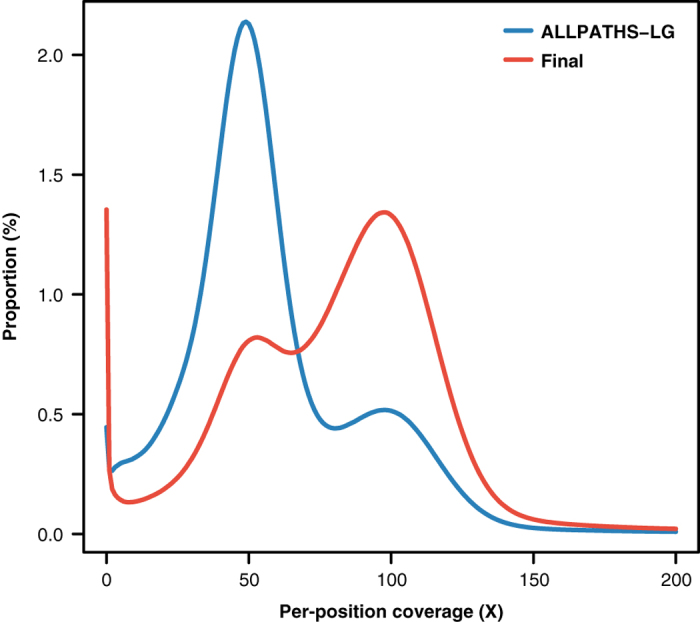

A double-peak k-mer distribution with the heterozygous peak (1st peak) being much higher than the homozygous peak (2nd peak) strongly indicates that E. chlorotica has a diploid genome with a high level of heterozygosity (Fig. 2). The rate of heterozygosity was estimated to be around 3.66% by GenomeScope (v1.0.0)38 with the k-mer frequency distributions generated by Jellyfish as inputs (Table 2). The heterozygosity rate of E. chlorotica (3.66%) was higher than those rates in the bivalve molluscs [Bathymodiolus platifrons (1.24%)19, Modiolus philippinarum (2.02%)19, Limnoperna fortune (2.3%)23, Pinctada fucata martensii (2.5–3%)27 and Chlamys farreri (1.4%)39] and a freshwater shelled gastropod [Pomacea canaliculata (1–2%)30], all also estimated by k-mer analyses, highlighting the difficulty of assembling the E. chlorotica genome.

Figure 2. A 17-mer frequency distribution of E. chlorotica based on 62.8 Gb Illumina data.

The first peak at coverage 43X corresponds to the heterozygous peak. The second peak at coverage 86X corresponds to the homozygous peak.

Genome assembly

The E. chlorotica genome was assembled by a hybrid and hierarchical assembly strategy as described below: (i) Clean reads from the Illumina short- and long-insert libraries were assembled into contigs using ALLPATHS-LG (v52488)40 with default parameters except setting HAPLOIDIFY = True, which yielded an initial assembly with a total length of 776 Mb and a contig N50 of 1.7 kb. This initial assembly was ~35% longer than the estimated genome size of 575 Mb, indicating that, for some genomic regions, two haploids were assembled separately due to high heterozygosity. Thus, (ii) we used HaploMerger2 (v20151124)41 to separate the two haploid sub-assemblies from the initial ALLPATHS-LG assembly, and an assembly with a total length of 575 Mb and contig N50 of 1.9 kb was produced. Next, (iii) we assembled a separate genome with the PacBio long-reads alone. Sequencing errors in the PacBio reads were first corrected by the clean Illumina reads from 170 bp and 500 bp short-insert libraries using PacBioToCA (v8.3)42 with parameter -length 400, and 5.36 Gb (9.32 X) error-corrected PacBio reads were retained (Table 1). Then the error-corrected PacBio reads were assembled using Canu (v1.4)43 with parameters minReadLength = 400 minOverlapLength = 400 contigFilter = 2 400 1.0 1.0 2, which produced an assembly with a total length of 469 Mb and contig N50 of 4.4 kb. (iv) The PacBio assembly was merged with the above HaploMerger2 assembly with Metassembler (v1.5)44, which resulted in an improved assembly with a total length of 535 Mb and contig N50 of 5.1 kb. (v) These resulting contigs were further assembled into scaffolds using the distance information provided by read pairs from the Illumina short- and long-insert libraries with SSPACE (STANDARD-3.0)45. Specifically, prior to scaffolding, the read pairs were aligned to the contigs using BWA (v0.6.2), and the insert size of each library was inferred from the statistics of a pre-run of SSPACE based on satisfied pairs in distance and orientation within contigs. Then scaffolding was performed with SSPACE using the estimated insert size of each library with the minimum allowed insert size error setting to be 0.3 for short-insert libraries and 0.5 for long-insert libraries. Subsequently, (vi) intra-scaffold gaps were filled using PBJelly from PBSuite (v15.8.24)46,47 with the error-corrected PacBio long reads by setting minReads = 3, followed by using GapCloser (v1.10.1)48 with the Illumina short-insert paired-end reads by setting library insert sizes according to SSPACE estimation as described above. (vii) The gap-filled scaffolds were submitted to HaploMerger2 again to reduce redundant sequences, followed by polishing with all the Illumina short-insert clean reads by PILON (v1.22)49. Finally, (viii) potential contaminants in the assembly including sequences from algal chloroplasts, slug mitochondria and adaptor/vector as identified by the NCBI contamination-screening pipeline were removed by an in-house script. The improvements of assembly generated at each step of the assembly process were presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Improvement in continuity and completeness of genome assembly generated by each of the eight assembly steps as stated in main text.

| Step | Assembly statistics |

Read mapping assessment |

BUSCO assessment |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly size (Mb) | Contig N50 (kb) | Scaffold N50 (kb) | Gap ratio (%) | Mapping rate (%) | Mapping rate in proper pairs (%) | Complete BUSCOs (%) | Fragmented BUSCOs (%) | Missing BUSCOs (%) | |||||||

| Note: For read mapping assessment, 500,000 pairs of clean reads were randomly selected from each of the six short-insert libraries, summed up to 3 M pairs of clean reads, which were aligned to each assembly by BWA-MEM (v0.7.16), followed by mapping rates counting by samtools flagstat (SAMtools v1.7). For BUSCO assessment, the percentages of complete, fragmented and missing BUSCOs were calculated by BUSCO (v3.0.2) for all the assemblies using 978 genes that are expected to be present in all metazoans. | |||||||||||||||

| i | 776 | 1.7 | NA | 0 | 95.27 | 65.07 | 30.2 | 37.5 | 32.3 | ||||||

| ii | 575 | 1.9 | NA | 0 | 93.26 | 63.91 | 29.2 | 38.9 | 31.9 | ||||||

| iii | 469 | 4.4 | NA | 0 | 81.42 | 79.45 | 54.5 | 26.6 | 18.9 | ||||||

| iv | 535 | 5.1 | NA | 0 | 95.20 | 79.79 | 64.9 | 25.3 | 9.8 | ||||||

| v | 583 | 5.6 | 457.2 | 8.27 | 95.35 | 82.77 | 92.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | ||||||

| vi | 584 | 27.6 | 455.6 | 3.03 | 96.39 | 84.12 | 92.8 | 1.6 | 5.6 | ||||||

| vii | 560 | 28.5 | 457.0 | 3.03 | 96.06 | 83.89 | 93.2 | 1.5 | 5.3 | ||||||

| viii | 557 | 28.5 | 442.0 | 3.04 | 95.93 | 83.87 | 93.3 | 1.4 | 5.3 | ||||||

The final result was a genome assembly with a total length of 557 Mb, comprising 9,989 scaffolds (Data Citation 6,7). The contig and scaffold N50s of this assembly were 28.5 kb and 442.0 kb, respectively, and unclosed gap regions represented 3% of the assembly (Table 4), exhibiting a continuity comparable to other published molluscan genomes (Data Citation 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21). In addition, GC content of the E. chlorotica assembly excluding gaps was estimated to be 37.7%.

Table 4. Comparison of assembly continuity and completeness for available mollusc genomes.

| Species | Sequencing technology | Genome coverage (X) | Assembly size (Mb) | Contig N50 (kb) | Scaffold N50 (kb) | Gap ratio (%) | Complete BUSCOs (%) | Fragmented BUSCOs (%) | Assembly Data Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: Sequencing technology and genome coverage were retrieved from the indicated reference or data citation for each species. Assembly size, Contig N50, Scaffold N50 and Gap ratio were calculated with an in-house script according to assemblies downloaded from NCBI or GigaDB with indicated Data Citations. The percentages of complete and fragmented BUSCOs were calculated by BUSCO (v3.0.2) for the all the assemblies using 978 genes that are expected to be present in all metazoans. | |||||||||

| Aplysia californica | Illumina | 66 | 927.31 | 9.59 | 917.54 | 20.44 | 92.5 | 2.0 | 8 |

| Bathymodiolus platifrons19 | Illumina | 319 | 1,658.19 | 10.74 | 343.34 | 11.77 | 93.6 | 2.5 | 9 |

| Biomphalaria glabrata20 | 454 | 28 | 916.39 | 7.30 | 48.06 | 1.91 | 88.9 | 4.9 | 10 |

| Crassostrea gigas21 | Illumina + Fosmid | 100 | 557.74 | 31.24 | 401.69 | 11.81 | 95.2 | 1.1 | 11 |

| Haliotis discus hannai22 | Illumina + PacBio | 322 | 1,865.48 | 14.19 | 200.10 | 6.25 | 91.6 | 4.9 | 12 |

| Limnoperna fortunei23 | Illumina + PacBio | 60 | 1,673.22 | 32.17 | 309.12 | 0.23 | 81.9 | 7.3 | 13 |

| Lottia gigantea24 | Sanger | 9 | 359.51 | 93.95 | 1,870.06 | 16.86 | 95.9 | 0.9 | 14 |

| Modiolus philippinarum19 | Illumina | 209 | 2,629.56 | 13.66 | 100.16 | 4.84 | 89.8 | 5.0 | 15 |

| Octopus bimaculoides25 | Illumina | 92 | 2,338.19 | 5.53 | 475.18 | 15.13 | 90.4 | 3.6 | 16 |

| Patinopecten yessoensis26 | Illumina | 297 | 987.59 | 37.58 | 803.63 | 8.10 | 94.3 | 1.3 | 17 |

| Pinctada fucata martensii27 | Illumina + BACs + RAD-seq | 150 | 990.98 | 21.52 | 59,032.46 | 11.18 | 87.8 | 3.5 | 18 |

| Pomacea canaliculata30 | Illumina + PacBio + Hi-C | 60 | 440.16 | 1072.86 | 31,531.29 | 0.02 | 95.8 | 0.7 | 19 |

| Radix auricularia28 | Illumina | 72 | 909.76 | 16.26 | 578.73 | 6.42 | 93.2 | 1.5 | 20 |

| Saccostrea glomerata31 | Illumina | 300 | 788.10 | 39.54 | 804.23 | 5.27 | 91.9 | 3.8 | 21 |

| Elysia chlorotica | Illumina + PacBio | 316 | 557.48 | 28.55 | 441.95 | 3.04 | 93.3 | 1.4 | 6,7 |

Repetitive element annotation

Repetitive elements in the E. chlorotica genome assembly were identified by homology searches against known repeat databases and de novo predictions. Briefly, we carried out homology searches for known repetitive elements in the E. chlorotica assembly by screening the Repbase-derived RepeatMasker libraries (v20170127) with RepeatMasker (v4.0.7; setting -nolow -norna -no_is)50 and the transposable element protein database with RepeatProteinMask (an application within the RepeatMasker package; setting -noLowSimple -pvalue 0.0001 -engine ncbi). For de novo prediction, RepeatModeler (v1.0.11)51 was executed on the E. chlorotica assembly to build a de novo repeat library for E. chlorotica. Then RepeatMasker was employed to align sequences from the E. chlorotica assembly to the de novo library for identifying repetitive elements. We also searched the genome assembly for tandem repeats using Tandem Repeats Finder (v4.09)52 with parameters Match = 2 Mismatch = 7 Delta = 7 PM = 80 PI = 10 Minscore = 50 MaxPeriod = 2000. Overall, we identified 176 Mb of non-redundant repetitive sequences, representing 32.6% of the E. chlorotica genome assembly excluding gaps (Table 5). Of note, the E. chlorotica repeat repertoire is highly diverse, comprising 33.5 Mb of DNA transposons (6.2% of the assembly), 30.3 Mb of long interspersed elements (LINEs; 5.6%), 19.4 Mb of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs; 3.6%), 14.4 Mb of long terminal repeats (LTRs; 2.7%), and 55.8 Mb of tandem repeats (10.3%; Table 5).

Table 5. Statistics for repetitive sequences identified in the E. chlorotica genome assembly according to detection method and biological category.

| According to method |

According to category |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool | Total repeat length (bp) | % of assembly | Category | Total repeat length (bp) | % of assembly |

| RepeatMasker | 51,434,719 | 9.52 | DNA | 33,515,133 | 6.20 |

| RepeatProteinMask | 12,318,674 | 2.28 | LINE | 30,286,412 | 5.60 |

| RepeatModeler | 127,879,238 | 23.66 | SINE | 19,423,541 | 3.59 |

| Tandem Repeats Finder | 55,758,776 | 10.32 | LTR | 14,375,566 | 2.66 |

| Combined | 176,039,101 | 32.57 | Tandem repeats | 55,758,776 | 10.32 |

Protein-coding gene annotation

We applied a combination of homology-based, transcriptome-based and de novo prediction methods to build consensus gene models for the E. chlorotica genome assembly. For homology-based prediction, protein sequences of Aplysia californica, Caenorhabditis elegans, Crassostrea gigas, Drosophila melanogaster, Lottia gigantea and Homo sapiens were first aligned to the E. chlorotica assembly using TBLASTN (blast-2.2.26)53 with parameters -F F -e 1e-5. Then the genomic sequences of the candidate loci together with 2 kb flanking sequences were extracted and submitted to GeneWise (wise-2.4.1)54 for exon-intron structure determination by aligning the homologous proteins to these extracted genomic sequences with settings of -sum -genesf -gff -tfor/-trev (-tfor for genes on forward strand and -trev for reverse strand). For transcriptome-based prediction, we collected published RNA-seq data from Pierce et al. (2012)13 (Data Citation 22) and Chan et al. (2018)15 (Data Citation 23), representing a total of 32.3 Gb of RNA reads from 13 samples across different developmental stages of E. chlorotica (from juvenile to adult) upon exposure to the algal food V. litorea. All the RNA-seq reads were first submitted to SOAPnuke (v1.5.6) for quality control by removal of adapter-contaminated reads and low-quality reads with parameters -Q 1 -G -t 15,0,15,0 -l 20 -q 0.2 -E 60 -5 1 for paired-end data from Pierce et al. (2012) and -Q 2 -G -t 15,0,0,0 -l 20 -q 0.2 -E 60 -5 1 for single-end data from Chan et al. (2018). We then mapped the clean RNA reads to the E. chlorotica genome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)55 and assembled transcripts by StringTie (v1.3.3b)56. For de novo prediction, we first randomly picked 800 transcriptome-based gene models with complete open reading frames (ORFs) and reciprocal aligning rates exceeding 80% against homologous proteins in the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (v2018_05)57 to train AUGUSTUS (v3.3.1)58 in order to obtain parameters suitable for E. chlorotica genes. Then we performed de novo prediction on the repeat-masked genome using AUGUSTUS with the obtained gene parameters and --uniqueGeneId = true --noInFrameStop = true --gff3 = on.

Finally, gene models from the above three methods were combined into a non-redundant gene set using a similar strategy as Xiong et al. (2016)59. Briefly, the homology-based gene models were first integrated with the transcriptome-based models to form a core gene set, followed by integration with the de novo models. Then de novo models not supported by homology-based and transcriptome-based evidence were also added to the core gene set if BLASTP (blast-2.2.26; parameters -F F -e 1e-5)53 hits could be found in the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (v2018_05). Finally, genes showing BLASTP (blast-2.2.26; parameters -F F -e 1e-5) hits to transposon proteins in the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (v2018_05) were removed from the combined gene set. We ultimately obtained 24,980 protein-coding genes with up to 22,717 (90.9%) supported by RNA-seq signal ( ≥ 5 RNA reads).

To assign gene names for each predicted protein-coding locus, we first mapped the protein sequences of all the 24,980 genes to the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (v2018_05) using BLASTP (blast-2.2.26)53 with parameters -F F -e 1e-5. Then the best hit of each gene was retained based on its BLASTP bit score, and the gene name of this best hit was assigned to the query E. chlorotica gene. A similar process was performed against the NCBI nr database (v20180315). In addition, we performed functional annotation with InterProScan (v5.29-68.0)60 to examine motifs, domains, and other signatures by searching against the databases including ProDom61, PRINTS62, Pfam63, SMART64, PANTHER65 and PROSITE66. To determine what pathways the E. chlorotica genes might be involved in, protein sequences of the E. chlorotica genes were searched against the KEGG database (v87)67 with BLASTP (blast-2.2.26) using parameters -F F -e 1e-5. As a result, 21,452 (85.9%) of the predicted protein-coding genes were successfully annotated by at least one of the four methods (Table 6).

Table 6. Summary of protein-coding gene annotation for the E. chlorotica genome assembly.

| Total number of protein-coding genes | 24,980 |

| Gene space (exon + intron; Mb) | 233.5 (41.9% of assembly) |

| Mean gene size (bp) | 9,634 |

| Mean CDS length (bp) | 1,344 |

| Exon space (Mb) | 33.2 (6.0% of assembly) |

| Mean exon number per gene | 6.8 |

| Mean exon length (bp) | 198 |

| Mean intron length (bp) | 1,433 |

| % of proteins with hits in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | 61.3 |

| % of proteins with hits in NCBI nr database | 84.1 |

| % of proteins with signatures assigned by InterProScan | 68.8 |

| % of proteins with KO assigned by KEGG | 64.7 |

| % of proteins with functional annotation | 85.9 |

Code availability

The bioinformatic tools used in this work, including versions, settings and parameters, have been described in the Methods section. Default parameters were applied if no parameters were mentioned for a tool.

Data Records

Raw reads from Illumina and PacBio sequencing are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with accession number SRP156455 and Bioproject accession PRJNA484060 (Data Citation 1) and are also deposited in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA) with accession number CNP0000110 (https://db.cngb.org/cnsa; Data Citation 2). Genome assembly, gene and repeat annotation of E. chlorotica generated in this study are deposited in the figshare repository (Data Citation 6) and NCBI under accession number GCA_003991915.1 (Data Citation 7).

Technical Validation

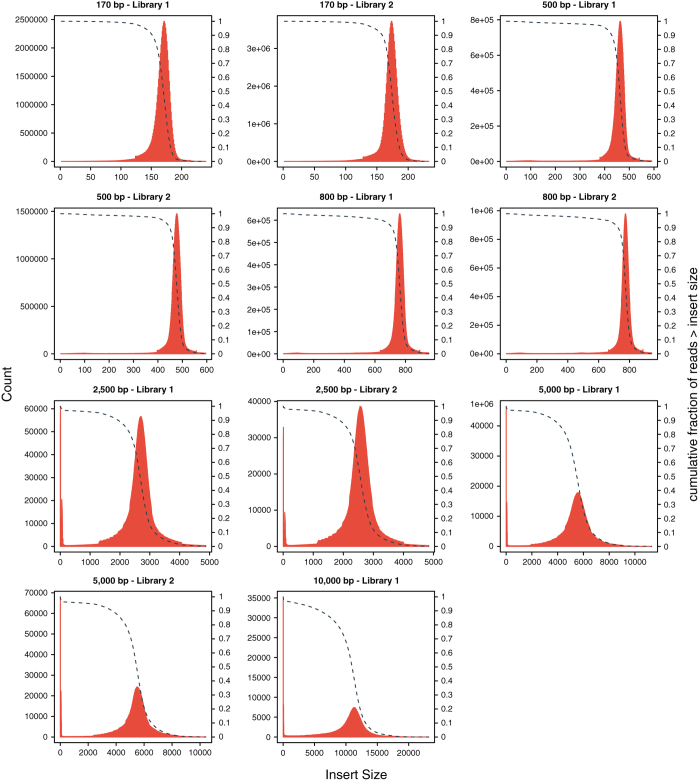

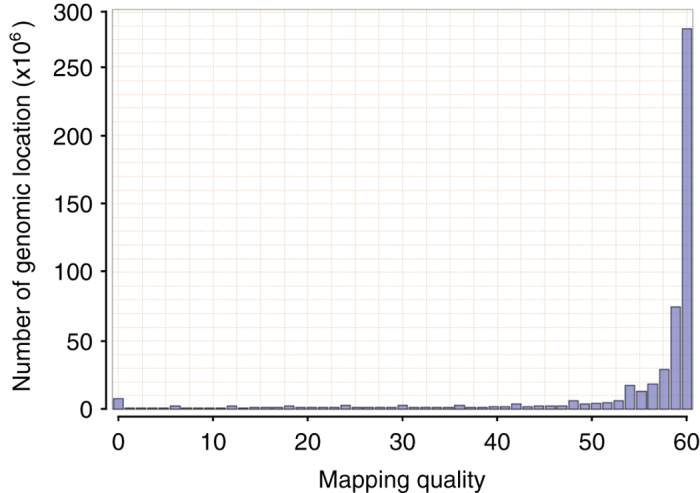

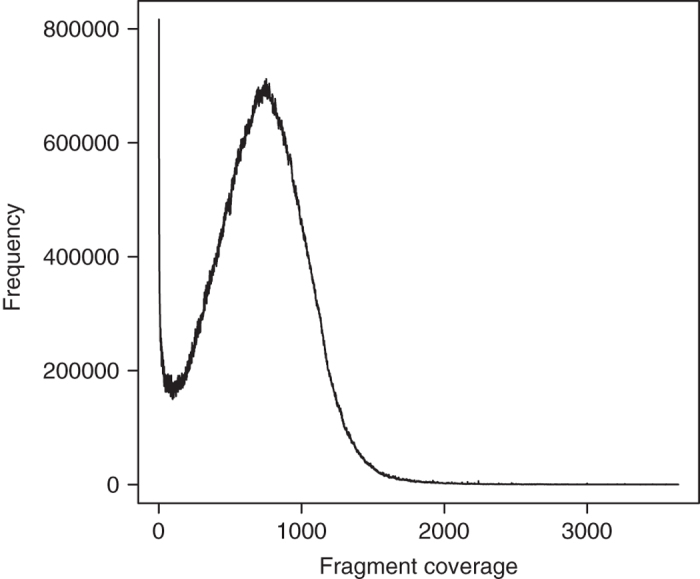

To evaluate the quality of the E. chlorotica assembly, we first aligned the 62.8 Gb Illumina short-insert clean reads which were previously used for k-mer analysis to the assembly using BWA-MEM (v0.7.16)35, and observed that 96% could be mapped back to the assembled genome with 85% of the mapped reads being aligned in proper pairs as counted by samtools flagstat (SAMtools v1.7)68. Qualimap 2 (v2.2.1)69 analysis reported a mean mapping quality (MQ) of 50.36 across all genomic positions in the final assembly with most positions having MQ of 60 (i.e. the highest MQ of BWA-MEM; Fig. 3). Moreover, single-position coverage analysis by samtools bedcov based on the above BWA-MEM alignment with PCR duplicates removed by Picard (v2.10.10)70 revealed that 98% of the assembly excluding gaps were covered by ≥ 5 reads and resulted in a per-position coverage distribution with its peak at 98X (Fig. 4). Of note, a minor peak at 49X was also observed (Fig. 4), implying that either a small amount of redundant sequences was still present in the final assembly, or the genomic regions corresponding to the minor peak were highly polymorphic between two haploids so that reads from the unassembled allele could not be aligned to the assembled allele by BWA-MEM due to low sequence identity. We also used Picard CollectInsertSizeMetrics (v2.10.10; setting MINIMUM_PCT = 0.5) to analyze the insert size distribution of each Illumina library based on BWA-MEM (v0.7.16) alignment of read pairs from each library, and observed that the estimated insert sizes of all the libraries matched their expected fragment sizes (Fig. 5). These results indicated that most sequences of the E. chlorotica genome that were captured by the sequencing platforms are present in the current assembly with proper orientation.

Figure 3. Mapping quality distribution of the E. chlorotica genome assembly.

The distribution was generated by Qualimap 2 (v2.2.1) with the BWA-MEM (v0.7.16) alignment of 62.8 Gb short-insert Illumina clean data as input.

Figure 4. Per-position coverage distributions of the initial ALLPATHS-LG assembly and the final genome assembly.

Per-position coverage was counted based on the BWA-MEM (v0.7.16) alignment of 62.8 Gb short-insert Illumina clean data with PCR duplicates removed by Picard (v2.10.10).

Figure 5. Fragment size distributions for all the Illumina libraries.

The distributions were generated by Picard CollectInsertSizeMetrics (v2.10.10; setting MINIMUM_PCT = 0.5) with BWA-MEM (v0.7.16) alignment of read pairs from each library as input.

The quality of the E. chlorotica assembly was further assessed by REAPR (v1.0.18)71, a tool that evaluates the accuracy of a genome assembly using mapped paired-end reads. Specifically, all the short-insert clean reads and the 10 kb mate-pair reads were aligned to the final assembly by reapr smaltmap for calling error-free bases and scaffolding errors, respectively. It is noteworthy that REAPR recommends using the longest insert data with sufficient fragment coverage for calling scaffolding errors while data from multiple long-insert libraries are available71. In our case, the fragment coverage of the 10 kb mate-pair library calculated by REAPR peaked at 752X (Fig. 6), far beyond the minimum requirement of 15X. Ultimately, REAPR judged 80.45% of the bases in the E. chlorotica assembly as error free (i.e. bases covered by ≥ 5 perfectly and uniquely mapped reads), and identified 123 collapsed repeats and a total of 2,943 fragment coverage distribution (FCD) errors. An FCD error usually represents incorrect scaffolding, a large insertion or deletion in the assembly71. Considering the high heterozygosity (3.66%), the high repeat content (32.6%) and especially the high tandem repeat content (10.3%) of this genome, which likely affect the performance of read mapping, we believe that the accuracy of the E. chlorotica assembly is acceptable. As a comparison, more than 7,000 FCD errors are recently reported in an improved genome assembly of the Atlantic cod Gadus morhua, of which the assembly size (643 Mb) and the tandem repeat content (11% of assembly) are actually comparable to the E. chlorotica assembly72.

Figure 6. Fragment coverage distribution of the 10 kb mate-pair library data generated by REAPR (v1.0.18).

Next, we employed Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO, v3.0.2)73 , a software package that can quantitatively measure genome assembly completeness based on evolutionarily informed expectations of gene content, to evaluate the completeness of the E. chlorotica assembly and 14 other published molluscan genomes using 978 genes that are expected to be present in all metazoans. We found that 927 (94.7%) of the expected genes were present in the E. chlorotica assembly with 913 (93.3%) and 14 (1.5%) identified as complete and fragmented, respectively. Only 51 (5.3%) genes were considered missing in the E. chlorotica assembly. The completeness of the E. chlorotica assembly based on BUSCO assessment was overall comparable to other published molluscan genome assemblies (Table 4).

Finally, we evaluated the completeness of the annotated gene set of E. chlorotica with BUSCO (v3.0.2) and DOGMA (v3.0)74, a program that measures the completeness of a given transcriptome or proteome based on a core set of conserved domain arrangements (CDAs). BUSCO analysis based on the metazoan dataset showed that 968 (98.9%) of the expected genes were present in the E. chlorotica gene set with 948 (96.9%) identified as complete. A higher number of expected genes were identified by BUSCO in the annotated gene set than in the E. chlorotica genome assembly, probably because searching genes in a transcriptome or proteome is simpler than in a genome. Meanwhile, DOGMA analysis based on PfamScan Annotations (PfamScan v1.5; Pfam v32.0)63 and the eukaryotic core set identified 93.3% of the expected CDAs in the annotated gene set. These results demonstrate the completeness of the annotated gene set of the E. chlorotica assembly.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Cai, H. et al. A draft genome assembly of the solar-powered sea slug Elysia chlorotica. Sci. Data. 6:190022 https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2019.22 (2019).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31501057), the State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Genomics (No. 2011DQ782025) in China and the MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI grants to T.N. (No. 22128008) and M.H. (No. 22128001) in Japan. Work in Tampa was supported by a donation to USF from a donor who wishes to remain anonymous.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Citations

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP156455

- 2019. CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive. CNP0000110

- 2010. GenBank. NC_011600.1

- 2016. GenBank. EU599581.1

- 2017. GenBank. KY115607.1

- Cai H., et al. . 2019. Figshare. [DOI]

- 2019. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003991915.1

- 2013. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000002075.2

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002080005.1

- 2013. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000457365.1

- 2012. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000297895.1

- 2017. GigaScience Database. [DOI]

- 2018. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003130415.1

- 2012. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000327385.1

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002080025.1

- 2015. NCBI Assembly. GCA_001194135.1

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002113885.2

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002216045.1

- 2018. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003073045.1

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002072015.1

- 2018. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003671525.1

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR8282417

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP136656

References

- Maeda T., Kajita T., Maruyama T. & Hirano Y. Molecular phylogeny of the sacoglossa, with a discussion of gain and loss of kleptoplasty in the evolution of the group. Biol Bull 219, 17–26 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpho M. E., Pelletreau K. N., Moustafa A. & Bhattacharya D. The making of a photosynthetic animal. J Exp Biol 214, 303–311 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. K. & Curtis N. E. Cell biology of the chloroplast symbiosis in sacoglossan sea slugs. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 293, 123–148 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. K., Curtis N. E. & Middlebrooks M. L. Sacoglossan sea slugs make routine use of photosynthesis by a variety of species‐specific adaptations. Invertebr Biol 134, 103–115 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. K., Curtis N. E., Hanten J. J., Boerner S. L. & Schwartz J. A. Transfer, integration and expression of functional nuclear genes between multicellular species. Symbiosis 43, 57 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. K., Curtis N. E. & Schwartz J. A. Chlorophyll a synthesis by an animal using transferred algal nuclear genes. Symbiosis 49, 121–131 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Rumpho M. E. et al. Horizontal gene transfer of the algal nuclear gene psbO to the photosynthetic sea slug Elysia chlorotica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 17867–17871 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpho M. E. et al. Molecular characterization of the Calvin cycle enzyme phosphoribulokinase in the stramenopile alga Vaucheria litorea and the plastid hosting mollusc Elysia chlorotica. Mol Plant 2, 1384–1396 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. A., Curtis N. E. & Pierce S. K. Using algal transcriptome sequences to identify transferred genes in the sea slug. Elysia chlorotica. Evol Biol 37, 29–37 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Soule K. M. & Rumpho M. E. Light-Regulated Photosynthetic Gene Expression and Phosphoribulokinase Enzyme Activity in the Heterokont Alga Vaucheria Litorea (Xanthophyceae) and Its Symbiotic Molluskan Partner Elysia Chlorotica (Gastropoda). J Phycol 48, 373–383 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B. J. et al. Mollusc-algal chloroplast endosymbiosis. Photosynthesis, thylakoid protein maintenance, and chloroplast gene expression continue for many months in the absence of the algal nucleus. Plant Physiol 124, 331–342 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanten J. J. & Pierce S. K. Synthesis of several light-harvesting complex I polypeptides is blocked by cycloheximide in symbiotic chloroplasts in the sea slug, Elysia chlorotica (Gould): A case for horizontal gene transfer between alga and animal? Biol Bull 201, 34–44 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. K. et al. Transcriptomic evidence for the expression of horizontally transferred algal nuclear genes in the photosynthetic sea slug, Elysia chlorotica. Mol Biol Evol 29, 1545–1556 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. A., Curtis N. E. & Pierce S. K. FISH labeling reveals a horizontally transferred algal (Vaucheria litorea) nuclear gene on a sea slug (Elysia chlorotica) chromosome. Biol Bull 227, 300–312 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. X. et al. Active Host Response to Algal Symbionts in the Sea Slug Elysia chlorotica. Mol Biol Evol 35, 1706–1711 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletreau K. N. et al. Sea slug kleptoplasty and plastid maintenance in a metazoan. Plant Physiol 155, 1561–1565 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya D., Pelletreau K. N., Price D. C., Sarver K. E. & Rumpho M. E. Genome analysis of Elysia chlorotica Egg DNA provides no evidence for horizontal gene transfer into the germ line of this Kleptoplastic Mollusc. Mol Biol Evol 30, 1843–1852 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder W. F. & Lindberg D. R. Phylogeny and Evolution of the Mollusca. (Univ of California Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. et al. Adaptation to deep-sea chemosynthetic environments as revealed by mussel genomes. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 121 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adema C. M. et al. Whole genome analysis of a schistosomiasis-transmitting freshwater snail. Nat Commun 8, 15451 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. et al. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature 490, 49–54 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam B. H. et al. Genome sequence of pacific abalone (Haliotis discus hannai): the first draft genome in family Haliotidae. Gigascience 6, 1–8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uliano-Silva M. et al. A hybrid-hierarchical genome assembly strategy to sequence the invasive golden mussel. Limnoperna fortunei. Gigascience 7, 1–10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simakov O. et al. Insights into bilaterian evolution from three spiralian genomes. Nature 493, 526–531 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertin C. B. et al. The octopus genome and the evolution of cephalopod neural and morphological novelties. Nature 524, 220–224 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. et al. Scallop genome provides insights into evolution of bilaterian karyotype and development. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 120 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X. et al. The pearl oyster Pinctada fucata martensii genome and multi-omic analyses provide insights into biomineralization. Gigascience 6, 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell T. et al. An annotated draft genome for Radix auricularia (Gastropoda, Mollusca). Genome Biol Evol (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun S. et al. The Whole-Genome and Transcriptome of the Manila Clam (Ruditapes philippinarum). Genome Biol Evol 9, 1487–1498 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. The genome of the golden apple snail Pomacea canaliculata provides insight into stress tolerance and invasive adaptation. Gigascience 7, 1–13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell D. et al. The genome of the oyster Saccostrea offers insight into the environmental resilience of bivalves. DNA Res 25, 655–665 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnepenninckx B., Backeljau T. & De Wachter R. Extraction of high molecular weight DNA from molluscs. Trends in genetics : TIG 9, 407 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience 7, 1–6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S. K., Mahadevan P., Massey S. E. & Middlebrooks M. L. A Preliminary Molecular and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Genome of a Novel Endogenous Retrovirus in the Sea Slug Elysia chlorotica. Biol Bull 231, 236–244 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (2013).

- Marcais G. & Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. G. et al. Characterizing and measuring bias in sequence data. Genome Biol 14, R51 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vurture G. W. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao W. et al. High-resolution linkage and quantitative trait locus mapping aided by genome survey sequencing: building up an integrative genomic framework for a bivalve mollusc. DNA Res 21, 85–101 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnerre S. et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 1513–1518 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Kang M. & Xu A. HaploMerger2: rebuilding both haploid sub-assemblies from high-heterozygosity diploid genome assembly. Bioinformatics 33, 2577–2579 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S. et al. Hybrid error correction and de novo assembly of single-molecule sequencing reads. Nat Biotechnol 30, 693–700 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 27, 722–736 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wences A. H. & Schatz M. C. Metassembler: merging and optimizing de novo genome assemblies. Genome Biol 16, 207 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M., Henkel C. V., Jansen H. J., Butler D. & Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27, 578–579 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English A. C. et al. Mind the gap: upgrading genomes with Pacific Biosciences RS long-read sequencing technology. PloS One 7, e47768 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English A. C., Salerno W. J. & Reid J. G. PBHoney: identifying genomic variants via long-read discordance and interrupted mapping. BMC bioinformatics 15, 180 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R. et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1, 18 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PloS One 9, e112963 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A. F., Hubley R. & Green P. RepeatMasker http://www.repeatmasker.org (2017).

- Smit A. & Hubley R. RepeatModeler http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/ (2017).

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 573–580 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W. & Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Clamp M. & Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res 14, 988–995 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Langmead B. & Salzberg S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12, 357–360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertea M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 33, 290–295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium, T. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 2699 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M., Diekhans M., Baertsch R. & Haussler D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z. et al. Draft genome of the leopard gecko. Eublepharis macularius. Gigascience 5, 47 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet F., Servant F., Gouzy J. & Kahn D. ProDom and ProDom-CG: tools for protein domain analysis and whole genome comparisons. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 267–269 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood T. K. et al. PRINTS and its automatic supplement, prePRINTS. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 400–402 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 42, D222–D230 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Doerks T. & Bork P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res 43, D257–D260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H., Poudel S., Muruganujan A., Casagrande J. T. & Thomas P. D. PANTHER version 10: expanded protein families and functions, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D336–D342 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist C. J et al. PROSITE, a protein domain database for functional characterization and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 38, D161–D166 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. & Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonechnikov K., Conesa A. & Garcia-Alcalde F. Qualimap 2: advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32, 292–294 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broad Institute. Picard https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard (2017).

- Hunt M. et al. REAPR: a universal tool for genome assembly evaluation. Genome Biol 14, R47 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torresen O. K. et al. An improved genome assembly uncovers prolific tandem repeats in Atlantic cod. BMC Genomics 18, 95 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simao F. A., Waterhouse R. M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E. V. & Zdobnov E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen E., Kremer L. P., Bornberg-Bauer E. & Kemena C. DOGMA: domain-based transcriptome and proteome quality assessment. Bioinformatics 32, 2577–2581 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP156455

- 2019. CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive. CNP0000110

- 2010. GenBank. NC_011600.1

- 2016. GenBank. EU599581.1

- 2017. GenBank. KY115607.1

- Cai H., et al. . 2019. Figshare. [DOI]

- 2019. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003991915.1

- 2013. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000002075.2

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002080005.1

- 2013. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000457365.1

- 2012. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000297895.1

- 2017. GigaScience Database. [DOI]

- 2018. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003130415.1

- 2012. NCBI Assembly. GCA_000327385.1

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002080025.1

- 2015. NCBI Assembly. GCA_001194135.1

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002113885.2

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002216045.1

- 2018. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003073045.1

- 2017. NCBI Assembly. GCA_002072015.1

- 2018. NCBI Assembly. GCA_003671525.1

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR8282417

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP136656