ABSTRACT

The family of heterogeneous ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) have multiple functions in RNA metabolism. In recent years, several hnRNPs have also been shown to be essential for the maintenance of transcriptome integrity, by preventing intronic cryptic splicing signals from mis-splicing of many endogeneous pre-mRNA transcripts. Here we discuss the possibility for a general role of this family of proteins and their expansion in transcriptome protection.

KEYWORDS: Hnrnps, introns, cryptic splicing, transcriptome integrity

Precursor-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcripts are packaged into heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) complexes upon transcription [1,2]. Although much has been learned about the multiple functions of hnRNPs in RNA metabolism, particularly pre-mRNA processing, little has been known about their protection of the whole transcriptome from processing errors, particularly cryptic splicing, an effect that has been observed for a number of hnRNPs by different groups.

Aberrant splicing could result from an estimated 15–60% of the mutations that cause human genetic diseases [3,4], leading to mRNA and/or protein changes and consequently protein and cell malfunctions. Even under normal conditions, cells face challenges to avoid the numerous cryptic splice sites, particularly in the introns [5].

Studies on the effects of genetic mutations have revealed an essential role of hnRNPs in preventing aberrant splicing of specific endogenous transcripts [6–10]. For instance, a mutation (G > A) in the alternative exon P3A of the CHRNA1 gene disrupts hnRNP L binding but enhances hnRNP LL binding to aberrantly increase usage of the exon in Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome [7]. In another case, hnRNP A1/A2 knockdown led to the inclusion (up to 95%) of a cryptic exon in the mutant ATM gene, while hnRNP A1 overexpression reduced the inclusion from 80% to 10% [8,9]. HnRNP mutations are known to cause aberrant splicing as well. For instance, in Drosophila, mutations in the hrp48 gene, a homologue of human hnRNP A/B, activates the third-intron splicing of the P-element in somatic tissues [11]. These and many other studies of specific transcripts of disease-related genes support that a group of hnRNPs repress aberrant splicing of endogenous transcripts.

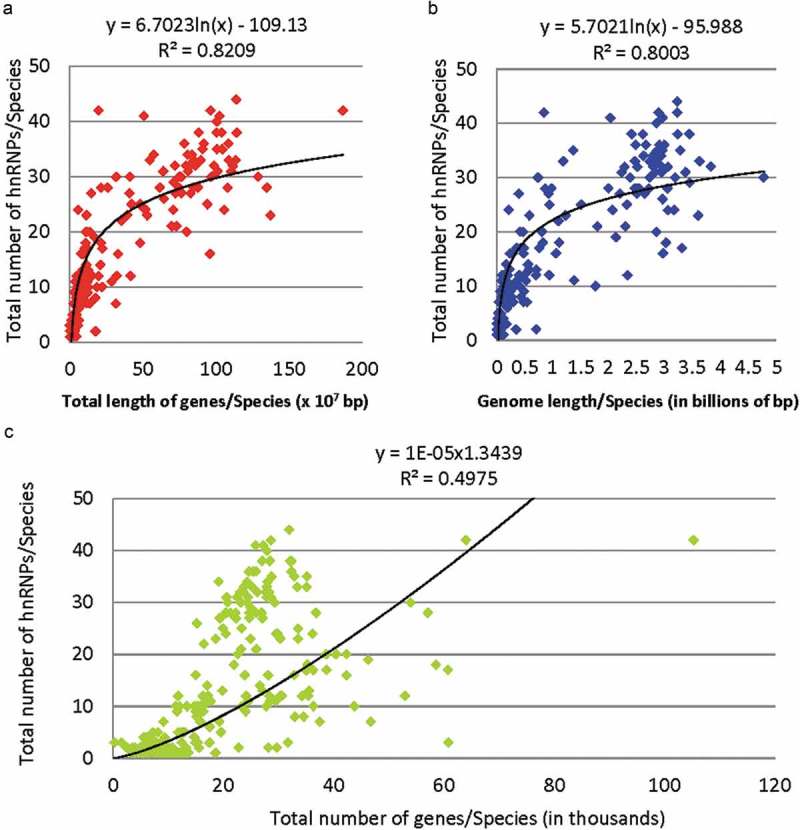

Beyond the above observations, the total number of hnRNPs and hnRNP-like proteins (containing domains homologous to known hnRNPs) correlates better with the total length of genes or genomes than with the total number of genes in 269 species (Figure 1). The number of hnRNP family members increased from several in many fungi and protists to more than 40 in some metazoans (e.g. 42 in humans and 44 in chimpanzees). They share structural features such as RNA recognition motifs (RRM) or K Homology (KH) type RNA binding domains (RBD), and glycine- or proline-rich regions (GRR or PRR) for interaction with RNA or other proteins [12]. The RBDs are the most conserved and others more divergent. Homologues such as PTBP1 and hnRNP L share substantial amino acid sequence identity (27–29% overall in humans, depending on the isoforms, same as the following) and even more so for paralogs such as hnRNP L and LL (54–58% identity). Besides the common features, the homologues have also diverged sufficiently to bind different RNA sequences with flexible but fairly constrained consensus motifs [13]. For example, hnRNP C, hnRNP L/LL, hnRNP F/H, PTBP1/P2 and TDP43 (with two RRM regions sharing 34–38% amino acid sequence identity with those of hnRNP D) prefer to bind U-rich, CA/AC-rich, GGG, CU-rich and UG-rich motifs, respectively [14–19]. Although the paralogs bind similar RNA motifs, those examined in detail still show different preferred sequences or different affinity to the same motifs [16,20,21]; so are the individual RRM domains or secondary structures within an hnRNP [18,22].

Figure 1.

Correlation of the total number of hnRNP or hnRNP-like proteins with the total length of genes (a), genome length (b) and the number of genes (c) in 269 species. The coefficients R2 show that the differentially expanded number of hnRNPs correlates better with the evolving total lengths of genes and genome sizes than the total number of genes among different species. The total number of hnRNPs of these Ensembl genomes/species were obtained from the NCBI Gene database by searching for the term ‘hnRNP’ in the ‘gene name’, ‘other designations’ or the ‘conserved domain’ sections of the records. The data are from 76 fungal, 120 metazoa, 30 plant and 43 protist species. The species with the highest number of hnRNPs in this search is the chimpanzee (44), followed by humans (42); the species with at least 1 hnRNP found are mostly fungi or protists. The presented trendline in each panel has the highest R2 among fitting curves using linear, exponential, logarithmic or power functions. In C, the gene numbers also positively correlate with the hnRNP numbers overall but in a more scattered way than in A and B. Even after the outlier species with total numbers of genes >50K were excluded, the R2 was 0.5587, still much lower than those in A and B. Search within only the ‘Domain name’ of NCBI Genes has resulted in similar correlations. A separate, manual verification of such hnRNPs of 21 species obtained a similar result as well, particularly with the correlation with gene lengths mainly in the total lengths of introns.

The expanded hnRNP family members could be non-redundant in not only RNA binding but also their effects on target exons or genes. For examples, PTBP1 and PTBP2 paralogs could have different target exons though with redundant ones as well in neuronal differentiation [23,24]; similarly, hnRNP L regulates gene expression and alternative splicing involved in hormone production distinctively from its paralog hnRNP LL though with some overlapping targets as well [25]; hnRNP E1 but not its paralog E2 suppresses HIV-1 gene expression [26]. Thus, even the paralogs could have distinct target differences in the regulation of gene expression, let alone the differences among homologues. Therefore, the expanded hnRNPs are diverse in both RNA binding and functions, and even the paralogs cannot always functionally substitute each other.

Based on the different target RNA motifs and effects on exons/genes by different hnRNPs, their expansion in metazoans probably matches the sequence complexity of pre-mRNA transcripts in different species. Although systematic assessments remain to be carried out, as an example for individual hnRNPs and corresponding RNA motifs, the hnRNP LL emergence in vertebrates accompanies the increased CA/AC content of the CaRRE1 element of the Slo1 gene (from one copy in the 3ʹ splice site of a fish Slo1 to as many as five copies in mammals) [27,28]. Similar co-appearance of hnRNP and RNA motifs are also observed in other cases [28].

Direct evidence has been obtained for the expanded hnRNPs to inhibit transcriptome-wide cryptic exons of endogenous transcripts in recent years, with large-scale sequencing of RNA samples upon loss-of-function of hnRNPs and analysis of reads mapped to the annotated introns [14,25,29–32]. For example, hnRNP C1 knockdown led to global increase of cryptic Alu exon formation and disease-associated deletion in Alu elements disrupted the ability of hnRNP C1 to inhibit the exon formation [14]. The effect is specific to hnRNP C1 since knockdown of PTB did not have the same effect. Transcriptome-wide cryptic exons are also detected in TDP43 knockout mouse cells, as well as in the post-mortem brain tissues of ALS-FTD with TDP43 proteinopathy [30], and the effect was rescuable for some of the cryptic exons by expressing a TDP43 fusion protein in knockout cells. PTBP1 or PTBP2 knockdown also caused usage of non-conserved cryptic exons and PTBP1 expression in PTBP1/2 knockdown cells restored the repression of cryptic exons supporting ‘a family of cryptic exon repressors’ [29]. Moreover, PTBP1 also interacts with Matrin-3 (with two RRMs sharing 38% identity with PTB RRM1) to inhibit the cryptic exons from LINE repeats [32], where the exon usage was increased upon knockdown of both proteins or upon LINE deletion. Similar repression of cryptic exons has also been reported recently for the hnRNP L by two labs independently [25,31].

Interestingly, in the case of hnRNP L/LL, there is little overlap of their target cryptic exons between the paralogs [25]. It is mainly hnRNP L that prevents cryptic exon usage. HnRNP LL, similar to that on the P3A exon [7], instead promotes inclusion of the hnRNP L-target cryptic exons when hnRNP L is knocked down. Moreover, the vertebrate hnRNP L-specific PRR domain mediates the inhibition of a group of cryptic exons in knockdown/rescue assays. These observations demonstrate an essential role of the evolutionarily evolved, paralog-specific domain in protecting transcriptome integrity, strongly supporting the importance of hnRNP expansion in this function.

Besides their repression of cryptic exons, the loss or weakening of hnRNP binding sites have been proposed to allow the emergence of novel exons from repeat sequences during evolution [14,32–34]. For some of the Alu exons included >50% in human cerebella, most of them are within the 5ʹ UTR to regulate translation and about 4% of them have evidence of coded peptides [35,36]. There are also Alu exons whose usage causes genetic diseases [37–41]. These indicate that some of them have been exonized into the normal transcriptome with biological effects though some others are cryptic exons only in disease tissues. Thus, while hnRNPs inhibit cryptic exons in the vast landscape of introns to maintain a stable transcriptome, this role could be disrupted in diseases, or in evolution to allow the emergence of novel exons.

Despite the progresses, there remain unanswered questions. For example, what are the effects of the many other hnRNPs on the cryptic splicing of endogenous pre-mRNA transcripts in the transcriptome? How could this relatively small number of proteins protect the tens of thousands of pre-mRNA transcripts with highly complex sequences? How do the multi-domain proteins interact with the introns of pre-mRNA transcripts to protect them from cryptic splicing?

To these questions, the following points perhaps could be considered. For relatively simple repetitive sequences in the introns, such as Alu, LINE, UG, CU and CA repeats, a specific set of hnRNPs appear to be sufficient to inhibit cryptic splicing of related intron sequences [14,25,29–32]. For more complex sequences, more versatile RNA binding or other properties would be helpful. For example, the four RRMs of PTBP1 have different sequence preferences. They are in an elongated molecule in solution and have been proposed to bind sequentially along the transcript [18,42,43]. Another interesting report shows that a single RRM domain could have two RNA binding sites in the Glorund, an hnRNP F/H homologue in drosophila [22], one in the loop for GGG and the other in the beta-sheets for an AU-rich structured motif, adding to the versatility of hnRNP recognition of different RNA motifs. Moreover, hnRNP genes can also be alternatively spliced to have splice variants with differential properties such as the PTBP1 isoforms [44]. Furthermore, posttranslational modifications could also affect their properties and consequently, the pre-mRNA-RNP complexes [27,45–47]. Lastly, many hnRNPs could interact with other hnRNPs or RBPs thereby bringing far-apart RNA motifs and/or exons to close proximity for splicing regulation [48,49]. Together, these multi-domains, splice variants, protein modifications and protein-protein interactions and their interplay could greatly add to the diverse properties of the expanded family of hnRNP proteins for them to match the complexity of pre-mRNA sequences, particularly in mammals.

Besides aberrant splicing, hnRNPs also inhibit cryptic polyadenylation sites and ensuing nonsense-mediated mRNA decay [25,50]. The prevention of aberrant splicing by the hnRNPs is thus likely part of their multiple roles to safeguard the transcriptome for proper functions, together with other RNA binding proteins (e.g. SRSF3, U2AF35 and SF3B1) or ribonucleoprotein complexes (e.g. U1 snRNP) [51–58].

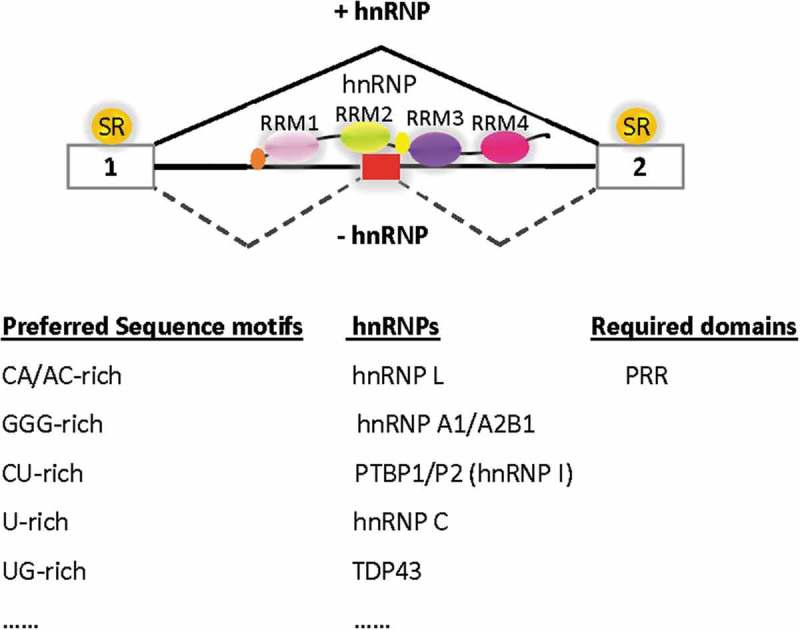

In summary, accumulating evidence suggest that the hnRNP family of proteins inhibit cryptic exons of endogenous transcripts in general to help protect transcriptome integrity (Figure 2). They have expanded likely to match the length/complexity of genes or genomes for this and many other roles in the life of RNA transcripts. More transcriptome-wide studies of hnRNPs, in particular their effects on the introns, will provide further insights into the protective role in biology and diseases.

Figure 2.

Transcriptome protection by different hnRNPs. hnRNP L binds to CA/AC-rich motifs to inhibit cryptic exon/splice sites requiring PRR domain. hnRNPA1/A2B1 (Das and Xie, unpublished observation), PTBP1/P2, hnRNP C and TDP43 bind to GGG, CU-, U- and UG-rich motifs, respectively, to prevent cryptic exon (red box) inclusion. PRR: Proline-rich region, RRM: RNA recognition motif. SR: arginine/serine-rich proteins that are generally splicing activators and interact with the exons. The ovals represent the different domains/regions of the hnRNP proteins. For simplicity, the pre-mRNA and hnRNP are ‘stretched’ linearly. The splicing pathways in the presence (+) or absence (-) of hnRNPs are indicated with lines above or below the transcript. There are likely more hnRNPs (……) to be identified to protect the endogenous pre-mRNA transcripts of the transcriptome.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada [RGPIN-2016-06004]; Manitoba Research Chair Fund; University of Manitoba Graduate Fellowship; Research Manitoba.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Schwartz H, Darnell JE.. The association of protein with the polyadenylic acid of HeLa cell messenger RNA: evidence for a “transport” role of a 75,000 molecular weight polypeptide. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:833–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pinol-Roma S, Choi YD, Matunis MJ, et al. Immunopurification of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles reveals an assortment of RNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 1988;2:215–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Krawczak M, Reiss J, Cooper DN. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum Genet. 1992;90:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lopez-Bigas N, Audit B, Ouzounis C, et al. Are splicing mutations the most frequent cause of hereditary disease? Febs Lett. 2005;579:1900–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Black DL. Finding splice sites within a wilderness of RNA. RNA. 1995;1:763–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Geuens T, Bouhy D, Timmerman V. The hnRNP family: insights into their role in health and disease. Hum Genet. 2016;135:851–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rahman MA, Masuda A, Ohe K, et al. HnRNP L and hnRNP LL antagonistically modulate PTB-mediated splicing suppression of CHRNA1 pre-mRNA. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pastor T, Pagani F. Interaction of hnRNPA1/A2 and DAZAP1 with an Alu-derived intronic splicing enhancer regulates ATM aberrant splicing. PloS One. 2011;6:e23349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pastor T, Talotti G, Lewandowska MA, et al. An Alu-derived intronic splicing enhancer facilitates intronic processing and modulates aberrant splicing in ATM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7258–7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kashima T, Rao N, David CJ, et al. hnRNP A1 functions with specificity in repression of SMN2 exon 7 splicing. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3149–3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hammond LE, Rudner DZ, Kanaar R, et al. Mutations in the hrp48 gene, which encodes a Drosophila heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle protein, cause lethality and developmental defects and affect P-element third-intron splicing in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7260–7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Han SP, Tang YH, Smith R. Functional diversity of the hnRNPs: past, present and perspectives. Biochem J. 2010;430:379–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Martinez-Contreras R, Cloutier P, Shkreta L, et al. hnRNP proteins and splicing control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;623:123–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zarnack K, Konig J, Tajnik M, et al. Direct competition between hnRNP C and U2AF65 protects the transcriptome from the exonization of Alu elements. Cell. 2013;152:453–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hui J, Hung LH, Heiner M, et al. Intronic CA-repeat and CA-rich elements: a new class of regulators of mammalian alternative splicing. EMBO J. 2005;24:1988–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Smith SA, Ray D, Cook KB, et al. Paralogs hnRNP L and hnRNP LL exhibit overlapping but distinct RNA binding constraints. PloSOne. 2013;8:e80701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dominguez C, Allain FH. NMR structure of the three quasi RNA recognition motifs (qRRMs) of human hnRNP F and interaction studies with Bcl-x G-tract RNA: a novel mode of RNA recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3634–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Oberstrass FC, Auweter SD, Erat M, et al. Structure of PTB bound to RNA: specific binding and implications for splicing regulation. Science. 2005;309:2054–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lukavsky PJ, Daujotyte D, Tollervey JR, et al. Molecular basis of UG-rich RNA recognition by the human splicing factor TDP-43. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1443–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schaub MC, Lopez SR, Caputi M. Members of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H family activate splicing of an HIV-1 splicing substrate by promoting formation of ATP-dependent spliceosomal complexes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13617–13626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Markovtsov V, Nikolic JM, Goldman JA, et al. Cooperative assembly of an hnRNP complex induced by a tissue-specific homolog of polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7463–7479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tamayo JV, Teramoto T, Chatterjee S, et al. The drosophila hnRNP F/H homolog glorund uses two distinct RNA-binding modes to diversify target recognition. Cell Rep. 2017;19:150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vuong JK, Lin CH, Zhang M, et al. PTBP1 and PTBP2 serve both specific and redundant functions in neuronal pre-mRNA splicing. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2766–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boutz PL, Stoilov P, Li Q, et al. A post-transcriptional regulatory switch in polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins reprograms alternative splicing in developing neurons. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1636–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lei L, Cao W, Liu L, et al. Multilevel differential control of hormone gene expression programs by hnRNP L and LL in pituitary cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38:e00651–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Woolaway K, Asai K, Emili A, et al. hnRNP E1 and E2 have distinct roles in modulating HIV-1 gene expression. Retrovirology. 2007;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu G, Razanau A, Hai Y, et al. A conserved serine of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L (hnRNP L) mediates depolarization-regulated alternative splicing of potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22709–22716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Xie J. Differential evolution of signal-responsive RNA elements and upstream factors that control alternative splicing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:4347–4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ling JP, Chhabra R, Merran JD, et al. PTBP1 and PTBP2 repress nonconserved cryptic exons. Cell Rep. 2016;17:104–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ling JP, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, et al. TDP-43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons is compromised in ALS-FTD. Science. 2015;349:650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McClory SP, Lynch KW, Ling JP. HnRNP L represses cryptic exons. RNA. 2018;24:761–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Attig J, Agostini F, Gooding C, et al. Heteromeric RNP assembly at LINEs controls lineage-specific RNA processing. Cell. 2018;174(1067–1081):e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Attig J, Ruiz de Los Mozos I, Haberman N, et al. Splicing repression allows the gradual emergence of new Alu-exons in primate evolution. elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lev-Maor G, Sorek R, Shomron N, et al. The birth of an alternatively spliced exon: 3ʹ splice-site selection in Alu exons. Science. 2003;300:1288–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shen S, Lin L, Cai JJ, et al. Widespread establishment and regulatory impact of Alu exons in human genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2837–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lin L, Jiang P, Park JW, et al. The contribution of Alu exons to the human proteome. Genome Biol. 2016;17:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Knebelmann B, Forestier L, Drouot L, et al. Splice-mediated insertion of an Alu sequence in the COL4A3 mRNA causing autosomal recessive Alport syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mitchell GA, Labuda D, Fontaine G, et al. Splice-mediated insertion of an Alu sequence inactivates ornithine delta-aminotransferase: a role for Alu elements in human mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:815–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Vervoort R, Gitzelmann R, Lissens W, et al. A mutation (IVS8+0.6kbdelTC) creating a new donor splice site activates a cryptic exon in an Alu-element in intron 8 of the human beta-glucuronidase gene. Hum Genet. 1998;103:686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ule J. Alu elements: at the crossroads between disease and evolution. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1532–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jourdy Y, Janin A, Fretigny M, et al. Reccurrent F8 intronic deletion found in mild hemophilia a causes alu exonization. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lamichhane R, Daubner GM, Thomas-Crusells J, et al. RNA looping by PTB: evidence using FRET and NMR spectroscopy for a role in splicing repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4105–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Petoukhov MV, Monie TP, Allain FH, et al. Conformation of polypyrimidine tract binding protein in solution. Structure. 2006;14:1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wollerton MC, Gooding C, Robinson F, et al. Differential alternative splicing activity of isoforms of polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB). RNA. 2001;7:819–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kumar A, Wilson SH. Studies of the strand-annealing activity of mammalian hnRNP complex protein A1. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10717–10722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cobianchi F, Calvio C, Stoppini M, et al. Phosphorylation of human hnRNP protein A1 abrogates in vitro strand annealing activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:949–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cartegni L, Maconi M, Morandi E, et al. hnRNP A1 selectively interacts through its Gly-rich domain with different RNA-binding proteins. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kim JH, Hahm B, Kim YK, et al. Protein-protein interaction among hnRNPs shuttling between nucleus and cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martinez-Contreras R, Fisette JF, Nasim FU, et al. Intronic binding sites for hnRNP A/B and hnRNP F/H proteins stimulate pre-mRNA splicing. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nazim M, Masuda A, Rahman MA, et al. Competitive regulation of alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation by hnRNP H and CstF64 determines acetylcholinesterase isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:1455–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Brooks AN, Choi PS, de Waal L, et al. A pan-cancer analysis of transcriptome changes associated with somatic mutations in U2AF1 reveals commonly altered splicing events. PloSOne. 2014;9:e87361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Przychodzen B, Jerez A, Guinta K, et al. Patterns of missplicing due to somatic U2AF1 mutations in myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2013;122:999–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Alsafadi S, Houy A, Battistella A, et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 mutations affect alternative splicing by promoting alternative branchpoint usage. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Darman RB, Seiler M, Agrawal AA, et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 hotspot mutations induce cryptic 3ʹ splice site selection through use of a different branch point. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1033–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kesarwani AK, Ramirez O, Gupta AK, et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 mutants recognize otherwise inaccessible cryptic 3ʹ splice sites within RNA secondary structures. Oncogene. 2017;36:1123–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Berg MG, Singh LN, Younis I, et al. U1 snRNP determines mRNA length and regulates isoform expression. Cell. 2012;150:53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Do DV, Strauss B, Cukuroglu E, et al. SRSF3 maintains transcriptome integrity in oocytes by regulation of alternative splicing and transposable elements. Cell Discov. 2018;4:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kaida D, Berg MG, Younis I, et al. U1 snRNP protects pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation. Nature. 2010;468:664–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]