Abstract

Objective

Relationships were examined between persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and incident type 2 diabetes, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and mortality.

Methods

In a nested case-control study, 300 persons without diabetes had baseline examinations between 1969 and 1974; 149 developed diabetes (cases) and 151 remained non-diabetic (controls) during 8.0 and 23.1 years of follow-up, respectively. POPs were measured at baseline. Odds ratios for diabetes were computed by logistic regression analysis. The cases were followed from diabetes onset to ESRD, death, or 2013. Hazard ratios for ESRD and mortality were computed by cause-specific hazard models. Patterns of association were explored using principal components analysis.

Results

PCB151 increased the odds for incident diabetes, whereas hexachlorobenzene (HCB) was protective after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, sample storage characteristics, glucose and lipid levels. Associations between incident diabetes and PCB or PST components were mostly positive but nonsignificant. Among the cases, 29 developed ESRD and 48 died without ESRD. PCB28, PCB49, and PCB44 increased the risk of ESRD after adjusting for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. Several PCBs and PSTs increased the risk of death without ESRD. The principal components analysis identified PCBs with low chlorine load positively associated with ESRD and death without ESRD, and several PSTs associated with death without ESRD.

Conclusions

Most POPs were positively, but not significantly associated with incident diabetes. PCB151 was significantly predictive and HCB significantly protective for diabetes. Among participants with diabetes, low-chlorine PCBs increase risk of ESRD and death without ESRD, whereas several PSTs predict death without ESRD.

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are synthetic organochlorine compounds that were used extensively between 1930 and the mid-1980s as herbicides and pesticides in agriculture, for control of vector-borne diseases such as malaria and typhus, as heat transfer and hydraulic fluids, and as plasticizers [1]. POPs enter the environment through these applications or through disposal of contaminated waste into landfills, and they accumulate in soil, sediments, and living organisms. The main route of human exposure to POPs is through food, particularly fish, meat, and dairy products, although contact through air and water also contribute to an individual’s lifetime exposure [1, 2]. Because of their high lipophilicity, POPs are stored primarily in fat tissue, remain in the body for long periods of time, and can act as endocrine and neuroendocrine disruptors [1–3].

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [4–13] suggest that POPs exposure increases the risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes; p,p’-DDE, the main metabolite of ppDDT, and trans-nonachlor most consistently predict diabetes [4–6, 12]. In those with diabetes, higher serum concentrations of POPs are associated with a higher prevalence of diabetic neuropathy [14]. A study of kidney biopsies in the arctic fox found a wide range of kidney tissue damage associated with exposure [15], but this association has not been studied in humans. POPs are also associated with early mortality in the elderly and in cigarette smokers [16–17].

This study examines the relationships between serum concentrations of POPs and incident diabetes in American Indians from central Arizona. This population has a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes, and resides on reservation land that is used extensively for agriculture, undergoing frequent applications of pesticides and herbicides. In participants with diabetes, we performed a follow-up analysis of the impact of POPs on the risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and mortality.

METHODS

Study population for association with incident diabetes

Between 1965 and 2007, American Indians from the Gila River Indian Community participated in a longitudinal diabetes study [18]. Each member of the community ≥5 years old was invited to have a research examination every 2 years that included a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Diabetes was defined by 2-hour post-load plasma glucose concentration (2hPG) ≥200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) or by clinical diagnosis between examinations. Participants from this longitudinal study who had no prior history of diabetes and were non-diabetic by OGTT at a baseline research examination attended between 1969 and 1974 were eligible for the present nested case-control study. Cases were participants who developed type 2 diabetes by the end of follow-up in 2007. Controls were defined as those who remained non-diabetic for ≥10 years after the baseline examination. POPs [37 polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and 9 persistent pesticides (PSTs)] were measured in serum collected at baseline. Participants from a wide range of ages were included, since incident type 2 diabetes is seen in children and adolescents, as well as adults, in this population [18, 19]. Presence or absence of diabetes at subsequent research examinations was confirmed by repeat OGTT. By design, the study included 100 males and 200 females, as the incidence of diabetes is higher in females. BMI was defined as weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2). Mean arterial pressure was calculated as MAP = 2/3 diastolic arterial pressure + 1/3 systolic arterial pressure.

The study was approved by the review board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Each participant gave informed consent or assent.

Study population for association with ESRD or mortality

Participants who developed diabetes in the case-control study were subsequently followed to examine the impact of exposure to POPs on ESRD or mortality without ESRD. For this analysis, the baseline examination was the date of diabetes diagnosis or the first research examination after the diagnosis of diabetes, if diabetes was diagnosed between research examinations. Diabetic ESRD was defined as initiation of dialysis, kidney transplant, or death from diabetic nephropathy. Deaths were attributed to diabetic nephropathy if the ICD-9 code 250.4 was specified as the underlying or a contributing cause of death. The causes of death were determined by review of clinical records, autopsy reports, and death certificates.

Laboratory measurements

POPs, cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured in serum samples collected at the baseline examination of the nested case-control study and stored at −20° C until 1985 and stored at −80° C thereafter until assay in 2011 by the Dioxin and Persistent Organic Pollutants Laboratory, Centers for Disease Control (Atlanta, Georgia, USA). All other variables used in the analyses were measured at the time of examination in the longitudinal observational study. Laboratory staff was blinded to the sample case or control status and participant characteristics. The stored serum samples were prepared for POPs assay using semiautomatic high-throughput extraction and clean-up methods on an automated Rapid Trace SPE Workstation (Zynmark, Hopkinton, MA) [20]. Serum concentrations of 46 POPs (for the complete list see Supplemental Table S4), including 37 polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and 9 pesticides (PSTs), were quantified using high resolution gas chromatography/isotope dilution high resolution mass spectrometry (GC/ID-HRMS) [21].

Results of spectrometry are given in wet weights, which represent the weight in concentration per the weight of serum measured (ng/g). Samples below the limit of detection (LOD) were given concentration values equal to the (LOD/√2) [22, 23]. If geometric means were less than the LOD, a mean value was not reported [22]. LODs were calculated using conventions described by Taylor [24]. PCB123, PCB189, Mirex, and γ-hexachlorocyclohexane were detectable in less than 25% of the samples, and were therefore excluded from further analyses. Reproducibility of analytes was assessed by measurement of 50 replicate samples blinded to the laboratory staff. Intraclass correlations of duplicate measurements for 35 PCBs and 7 PSTs ranged from 0.774 to 0.995 (median=0.979). Each single form of PCB is called a congener, and is identified by a number.

Statistical Analysis

Wet weight concentrations of POPs are used in all analyses. Baseline characteristics are presented as medians (inter-quartile range, IQR). Differences between cases and controls were assessed by the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. POPs and trait correlations were calculated using Spearman’s correlations and the results are presented as the median (IQR) of the 42 correlations for each individual trait. A correlation coefficient with an absolute value of r ≥0.11 corresponds to a statistically significant correlation at α=0.05 for a sample size of n=300. Differences in unadjusted POPs serum concentrations between sexes were tested using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Negative values indicated higher POPs levels in men. An absolute difference of 15 in the mean Wilcoxon score of POPs exposure is significant at α = 0.05 with a sample size of n=100 and n=50 for women and men, respectively. The amount of water loss that occurred during long-term frozen storage of serum samples was estimated as the ratio of serum cholesterol concentration measured in the sample at the time of collection to the serum cholesterol concentration measured at the time of POPs assay (water loss = fresh sample cholesterol (mg/dl) ÷ thawed sample cholesterol (mg/dl)).

POPs concentrations in this American Indian population were compared with those in the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 participants [22], representative of the general United States population. The levels are for lipid-adjusted POPs. NHANES data are not available for the same period in which samples in the American Indian population were obtained (1969–1974). Accordingly, for a fairly reasonable parallel, we present data from NHANES 2003–04 participants 60 years and older, whose average age at the time of exposure was comparable to that of this study’s participants.

Logistic models of POPs and type 2 diabetes

The association of serum POPs concentrations with incident type 2 diabetes was explored by logistic regression analysis with case or control as the dependent variable, using 5 different models: unadjusted; age- and sex-adjusted; BMI, cholesterol, TG, and 2hPG adjusted; age, sex, BMI, cholesterol, TG, and 2hPG adjusted; age, sex, BMI, cholesterol, TG, 2hPG, storage time, and cholesterol ratio adjusted. The fully adjusted models included clinical variables that are known risk factors for type 2 diabetes and were measured at baseline. Covariates were added stepwise and tested for explanatory power using the likelihood ratio test. Lipids were included as covariates in the models, instead of using ratio “adjustment”, as the division of POPs serum concentrations by serum lipids was observed to be highly prone to bias [25, 26]. The independent covariates were centered on the mean and the POPs are included individually as logged values (i.e., the five models were run for each individual analyte). The ORs for incident diabetes are reported per one standard deviation increase in the individual log(PCB) and log(PST) concentrations. Model fit was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic [27].

Principal components analysis was performed on the correlation matrix of the 35 PCB congeners and the 7 PSTs. Principal components analysis is a data reduction technique that produces successive linear combinations of the variables (principal components), each accounting for most of the remaining variance under the constraint that it is orthogonal to the preceding components, i.e. has no correlation with preceding components. The variance explained by each successive non-zero congener (eigenvalue) was extracted and the eigenvalues ≥1 were retained [28]. Eigenvalues <1.00 did not meet criteria for analysis in logistic regression models. PCB components 1, 2, and 3 collectively explained 84.4% of the variation in PCB exposure in the study population. Component 1 explained 61.1% of the variation, with PCBs containing ≥6 chlorine atoms displaying highest loadings for this component; component 2 explained 13.4% of the variation and displayed highest loadings for PCBs with 4–6 chlorine atoms; component 3 explained 9.9% of the variation in PCB exposure and included high factor load for PCBs with ≤4 chlorine atoms. The congeners represented in each principal component and the variation explained by each component are shown in Supplemental Table S1. Factor loadings for the two PST components identified are presented in Supplemental Table S2. The two components explained 78.2% of the variation in PST exposure. Supplemental Figure S1 shows the eigenvalues of the principal components for the 35 PCBs and 7 PSTs. Only the first three PCB principal components (PC1 to PC3) and the first two PST principal components (PC1 and PC2) were included in the logistic regression models, as these explain the majority of the sample variance. The five model adjustments described above were also applied with individual principal components.

POPs predicting ESRD or mortality

Patients with diabetes were followed from their first diabetic examination until December 31, 2013; ESRD; or natural death. Two of the 149 subjects with type 2 diabetes developed ESRD prior to their first eligible diabetic examination, leaving 147 subjects followed for these outcomes. Deaths were considered natural if they were due to disease (ICD-9 codes 001.0–799.9). For all deaths, the accuracy and completeness of the underlying cause was determined by review of clinical records, autopsy reports, and death certificates. Hazard ratios per one standard deviation increase in individual POP congeners were computed using cause-specific hazard models [29, 30]. For each POP we evaluated several model adjustments, the fully adjusted models including age, sex, MAP, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), total cholesterol, triglycerides, and 2hPG; the most parsimonious models were adjusted for age, sex, and MAP. The Cox regression models were also applied for the three PCB principal components and the two PST principal components.

All models were tested for proportionality assumptions and interactions, neither being found significant. Correction for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni procedure was not applied, because it assumes independence among tests and these measures are highly correlated. Calculations were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA 13 software for the principal component analysis.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the cases and controls at baseline are shown in Table 1. Age, BMI, triglycerides, 2hPG, and MAP were higher in cases than in controls. The correlation between storage time and water loss was low, but statistically significant (r=0.25, p <0.001). The median water loss was 0.95 ± 0.14, indicating a 5% water loss for the stored samples. Men had significantly higher concentrations than women for 33 POPs in the cases and for 32 POPs in the controls. Median (IQR) differences in POPs concentrations between men and women were −37.7 ng/g (−41.1 to −17.5 ng/g), and −31.1 ng/g (−37.3 to −16.5 ng/g), in cases and controls, respectively. Supplemental Table S3 shows the median (IQR) of Spearman’s correlations between age, BMI, triglycerides, cholesterol, and glucose with all 42 POPs. All POPs except for PCB44, PCB49, PCB52, and PCB110 correlated with age. Only oxychlordane and trans-nonachlor correlated with 2hPG despite a broad range of POPs and 2hPG concentrations. All POPs correlated with triglycerides, 75% of these correlation coefficients were ≥0.35. PCB44, PCB49, o,p’-DDT, and p,p’-DDT were the only POPs not correlated with cholesterol. Supplemental Table S4 shows serum POPs levels in the American Indian population sampled between 1969 and 1974 and NHANES 2003–2004 participants ≥60 years old. Average PST and PCB concentrations were generally 3–4 times higher in the American Indians than in the U.S. population during 2003–2004. One POP, p,p’-DDT, was 240 times more concentrated in the American Indians than in the U.S. population in 2003–2004.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cases (American Indians who developed type 2 diabetes) and controls (remained non-diabetic during follow-up).

| Variable | Case (n=149) | Controls (n=151) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 50 (34) | 50 (33) | |

| Age (yrs) | 28.3 (18.8–40.6) | 21.0 (21.2–37.3) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4 (27.3–33.3) | 27.4 (24.7–31.4) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 171 (112–245) | 123 (90–188) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 174 (152–204) | 180 (153–210) | 0.49 |

| 2hPG (mg/dl) | 109 (94–127) | 96 (86–113) | <0.001 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 92 (85–100) | 87 (81–95) | 0.003 |

| Follow-up (years) | 8.0 (3.8 to 10.9) | 23.1 (17.0–31.5) | <0.001 |

| Storage time (years) | 39.3 (38.8–40.1) | 39.3 (38.6–39.8) | 0.20 |

Values are medians (IQR).

BMI, body mass index; 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose concentration after an oral glucose tolerance test.

Association of POPs with type 2 diabetes

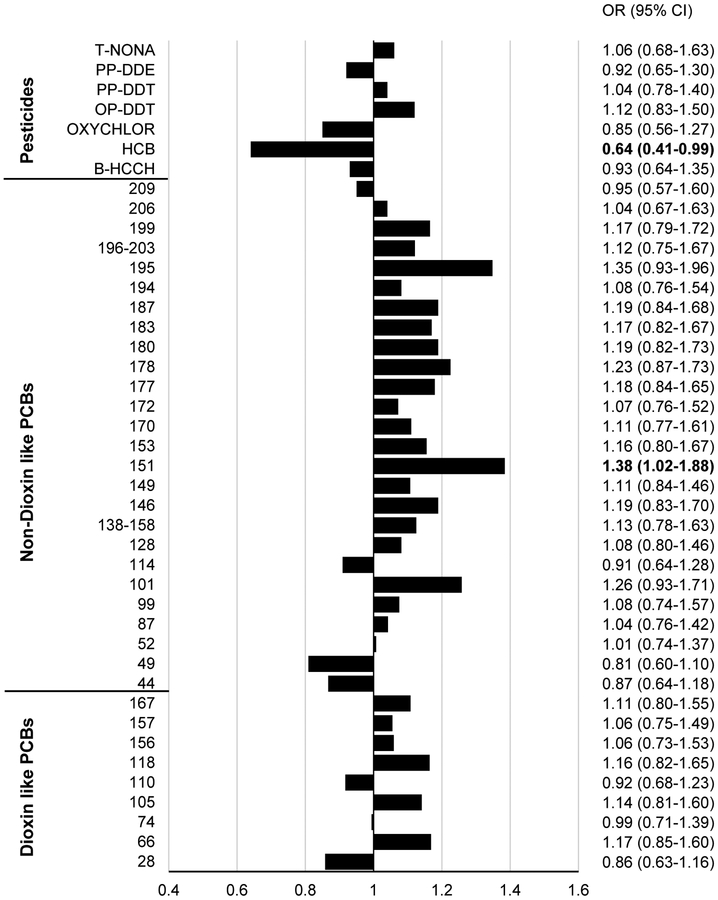

The unadjusted results were largely in the direction of a positive association with being a case, yielding ORs significantly >1 for several PCBs and PSTs (Supplemental Table S5). The odds for type 2 diabetes were higher with each standard deviation increase in log(PCB101), log(PCB151), and log(OP-DDT) in the age-, sex-adjusted model. In all models PCB151 was significantly positively predictive and in all but the minimally adjusted models, HCB is significantly protective. Figure 1 shows the fully adjusted ORs of type 2 diabetes and 95% confidence limits for each analyte.

Figure 1. The odds ratios (bars) of type 2 diabetes per standard deviation increase in individual POPs.

Estimates are adjusted for age, sex, BMI, 2hPG, sample water loss, storage time, cholesterol, and triglycerides. Corresponding point estimates and 95% CI are shown to the right of the graph. The odds ratios are per one standard deviation in the log(PCB) or log(PST). Dioxin-like PCBs characterized as: aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) binder; planar; chlorine para-substituted and non- or mono-ortho-substituted; Non-dioxin-like PCBs characteristics: poorly binds to AhR; non-planar; chlorine di-, tri-, or quatro-ortho-substituted.

The unadjusted and adjusted associations between incident diabetes and the individual PCB or PST components were mostly positive but not significant, indicating no pattern of association with type 2 diabetes (Table 2). Including all PCB and PST components in the models also yielded non-significant associations with incident type 2 diabetes.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted association between PCB and PST principal components and incident type 2 diabetes.

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates: | None | Age sex | BMI cholesterol TG 2hPG | Age sex BMI cholesterol TG 2hPG | Age sex BMI cholesterol TG 2hPG storage time cholesterol ratio | |||||

| POP | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| PCB PC1 | 1.21 | 0.94–1.55 | 1.16 | 0.88–1.52 | 1.19 | 0.85–1.66 | 1.16 | 0.82–1.63 | 1.12 | 0.79–1.58 |

| PCB PC2 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.24 | 0. 90 | 0.69–1.18 | 0.90 | 0.67–1.20 | 0.83 | 0.57–1.21 | 0.84 | 0.57–1.23 |

| PCB PC3 | 1.04 | 0.83–1.31 | 1.07 | 0.85–1.35 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.24 | 0.99 | 0.78–1.26 | 0.88 | 0.67–1.17 |

| PST PC1 | 1.25 | 0.99–1.58 | 1.13 | 0.84–1.52 | 1.06 | 0.78–1.46 | 0.93 | 0.63–1.36 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.27 |

| PST PC2 | 1.11 | 0.88–1.39 | 1.18 | 0.93–1.51 | 1.15 | 0.89–1.49 | 1.19 | 0.92–1.55 | 1.14 | 0.87–1.51 |

Model 3 is the most parsimonious model including only covariates that are significantly predictive.

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose; OR, odds ratio; PC, principal component; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyls; POPs, persistent organic pollutants; PST, pesticides; TG, triglycerides

Risk of ESRD or death

Among those who developed type 2 diabetes, 29 patients subsequently progressed to ESRD, 48 died without ESRD, and 17 died after starting dialysis. The characteristics of this follow-up cohort at the time of the first diabetic examination are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the 147 participants with type 2 diabetes at their first diabetic examination. Two of the 149 subjects with type 2 diabetes developed ESRD prior to their first eligible diabetic examination, leaving 147 subjects followed for these outcomes.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Male n (%) | 50 (34) |

| ESRD events (n) | 29 |

| Deaths (n) | 48 |

| Age (years) | 37.9 (27.8–49.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.1 (29.4–37.3) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 167 (146 to 189) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 114 (98 to 130) |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%)* | 8.3 (6.5–9.9) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 91 (83–100) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 115 (101–128) |

| ACR (mg/g)** | 19 (10–71) |

| Follow-up Time for ESRD (yrs) | 26.8 (16.0–32.4) |

| Follow-up Time for mortality (yrs) | 29.4 (19.4–34.9) |

Values are median (interquartile range) unless otherwise noted.

n=116 patients;

n=52 patients. These patients were followed for the onset of ESRD or death without ESRD. ACR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate by the CKD-EPI equation; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

The risk of ESRD increased with each standard deviation increase in PCB28, PCB49, and PCB44 after adjusting for age, sex, MAP, eGFR, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and 2hPG (Supplemental Table S6). In all but the unadjusted model, PCB28 was significantly positively predictive, whereas PCB49 and PCB44 became significantly predictive in models with more covariate adjustment. The risk of death without ESRD increased with each standard deviation increase in several PCBs and PSTs, as shown in Supplemental Table S6. The effect of oxychlordane was the most consistent across models, whereas the other associations became significant with more adjustment. The most common causes of death without ESRD were malignancies (n=8), cardiovascular disease (n=7) and alcoholic liver disease (n=6). Five of the eight malignancies affected the gastrointestinal tract (gallbladder, liver, pancreas, and colon). By contrast, among those who died on dialysis, malignancy was recorded as an underlying cause of death in one person only.

The unadjusted and adjusted associations between individual PCB or PST principal components and risk of ESRD or death without ESRD are shown in Table 4. The fully adjusted PCB component 2 was associated with both ESRD (HR=3.32, 95% CI 1.07–10.27) and death without ESRD (HR=8.11, 95% CI 3.11–21.18). PCB component 3 was positively predictive of ESRD only, regardless of adjustment. Although both PST components were associated with risk of death without ESRD, the direction of the association was positive for component 1 (HR=1.75, 95% CI 1.19–2.58) and negative for component 2 (HR=0.65, 95% CI 0.45–0.93) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between POPs principal components, ESRD, or death without ESRD in persons with type 2 diabetes.

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates: | None | Age sex | Age sex MAP | Age sex MAP cholesterol TG 2hPG | Age sex MAP eGFR TG cholesterol 2hPG | |||||

| ESRD | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

| PCB PC1 | 0.84 | 0.52–1.34 | 0.99 | 0.68–1.46 | 1.01 | 0.68–1.49 | 0.94 | 0.60–1.46 | 0.94 | 0.61–1.45 |

| PCB PC2 | 1.32 | 0.67–2.59 | 2.25 | 0.93–5.43 | 2.49 | 0.98–6.31 | 2.86 | 0.99–8.29 | 3.32 | 1.07–10.27* |

| PCB PC3 | 1.27 | 0.95–1.70 | 1.39 | 0.99–1.93 | 1.43 | 1.02–2.01* | 1.53 | 1.08–2.17* | 1.53 | 1.08–2.18* |

| PST PC1 | 0.86 | 0.55–1.34 | 1.06 | 0.65–1.71 | 1.06 | 0.66–1.72 | 0.95 | 0.50–1.79 | 0.94 | 0.50–1.77 |

| PST PC2 | 1.07 | 0.72–1.59 | 0.99 | 0.65–1.50 | 0.97 | 0.63–1.50 | 0.96 | 0.63–1.44 | 0.95 | 0.63–1.45 |

| Death | ||||||||||

| PCB PC1 | 1.16 | 0.97–1.38 | 0.97 | 0.69–1.36 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.46 | 1.21 | 0.91–1.61 | 1.20 | 0.91–1.59 |

| PCB PC2 | 2.91 | 1.85–4.58* | 1.47 | 0.83–2.61 | 1.68 | 0.93–3.01 | 6.30 | 2.56–15.45* | 8.11 | 3.11–21.18* |

| PCB PC3 | 0.75 | 0.50–1.11 | 0.81 | 0.59–1.11 | 0.86 | 0.61–1.21 | 0.93 | 0.66–1.30 | 0.91 | 0.65–1.29 |

| PST PC1 | 1.68 | 1.34–2.10* | 1.13 | 0.84–1.54 | 1.22 | 0.89–1.66 | 1.74 | 1.19–2.54* | 1.75 | 1.19–2.58* |

| PST PC2 | 0.65 | 0.50–0.83* | 0.79 | 0.59–1.05 | 0.78 | 0.57–1.06 | 0.66 | 0.46–0.95* | 0.65 | 0.45–0.93* |

Significant associations. Model 3 was chosen as the most parsimonious, including covariates that are significantly predictive. CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; 2hPG, 2-hour plasma glucose; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PC, principal component; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyls; POPs, persistent organic pollutants; PST, pesticides; TG, triglycerides.

DISCUSSION

POPs concentrations in samples collected in this population between 1969 and 1974 were similar to those reported in the U.S. population for the same period [31] and nearly 5-fold higher than reported in NHANES 2003–2004. Exposure to PCB151 and HCB was significantly associated with incident type 2 diabetes, with PCB151 being a risk factor and HCB being protective. These associations were consistent across models adjusted for different sets of covariates. Although PCB151 and HCB had the strongest predictive value for type 2 diabetes, several other analytes were in the direction of a positive association with being a case with no or less covariate adjustment. These results add credence to studies which show associations of POPs with metabolic diseases, although the analytes most strongly associated with diabetes vary across studies [7, 9, 10, 12, 32]. The negative association between HCB and type 2 diabetes is novel, and different from previous studies showing either positive [8–10, 32] or no associations [33]. A previous study using non-targeted metabolomics analysis found that HCB level was negatively associated with two glycerophospholipid metabolites and positively with three other metabolites: lysophosphatidylethanolamine, docosahexaenoic acid, and a cinnamic acid related metabolite [34]. It has been hypothesized that through these associations HCB might influence lipid biosynthesis, however, the direction of these effects and the precise relationship between HCB, lipids, and regulatory factors are not clear. Discordant findings could be due to studies employing surrogate definitions for diabetes (such as self-report, fasting plasma glucose or medication), differences in exposure measurements, reduced follow-up time, and high correlations among POPs and different lipid adjustments. In particular, the extent of the confounding and/or causal PCB-lipid relationship relative to the outcome of interest remains unclear [35–36]. A systematic review of 72 cross-sectional and longitudinal studies exploring associations between POPs and diabetes found significant heterogeneity among studies, with different approaches to lipid adjustment impeding a pooled analysis of the results [12]. Biological mechanisms by which POPs interfere with lipid homoeostasis include antagonism of PPARγ leading to insulin resistance [37, 38], DNA hypomethylation [39, 40], and induction of P450 enzymes with increased production of cholesterol and triglycerides [36]. High concentration of circulating lipids, on the other hand, increases the measured concentration of POPs in the serum. Prospective analyses of POPs contribution to increased triglyceride levels and diminished insulin resistance may determine the functional aspects of POPs contribution to type 2 diabetes.

Among individuals who developed type 2 diabetes, PCB28, PCB49, and PCB44 significantly increased the risk of ESRD by 75%, 64%, and 59% respectively. These analytes are non-dioxin-like PCBs with less than 4 chlorine atoms, and high factor loadings for PCB principal component 3, which was also consistently predictive of ESRD across various model adjustments.

Indeed, the major route of excretion for low chlorinated PCB congeners is the urinary tract, after being transformed into hydroxylated derivatives, a process that might contribute to their renal accumulation [41]. Little is known, however, regarding the biological and toxicological activity of these PCBs or their metabolites; experimental studies on renal accumulation and histopathologic effects of individual PCBs are available for PCB28 only, and even for this analyte the results are inconsistent [41].

A study comparing kidney tissue from farmed arctic foxes fed a high POPs diet for two years found significantly higher prevalence of renal lesions than in control animals [15]. The pattern of lesion suggested that the exposed animals were more frequently infected, possibly due to POPs induced immunosuppression, and they appeared to experience accelerated ageing. A cross-sectional study including patients with diabetes and various stages of kidney disease showed a strong association between aryl hydrocarbon receptor transactivating (AhRT) activity and albuminuria, but no association with serum creatinine concentrations [42]. Dioxin like congeners (such as PCB 28) are ligands of the arylhydrocarbon receptor (AhR), and might explain the relationship between AhRT activity and diabetic nephropathy. After binding to AhR, the PCBs might induce kidney tissue damage through several mechanisms, including increased production of reactive-oxygen species, mitochondrial toxicity, and modulation of genes involved in remodeling of extracellular matrix, although none of these pathways are known to be specific to the kidneys.

Death without ESRD in those with diabetes was predicted by higher exposure to PCBs 74, 99, 118, 105, 138–158, 167, 156, 157, 199, 196–203, 194, 206, 209, and 114, hexachlorobenzene, β-hexachlorocyclohexane, oxychlordane, trans-nonachlor, and p,p’-DDE. Although each marker was considered separately, we also reduced the number of independent hypotheses by using the principal components analysis, which identified POPs exposure patterns that are associated with increased risk of death after developing type 2 diabetes. PCB component 2 loaded highly on dioxin- and non-dioxin-like PCBs with 4–6 chlorine atoms and was associated with significantly higher risk of death without ESRD. PST component 1 loaded highly on β-hexachlorocyclohexane and p,p’-DDE, which were less represented in component 2, and was associated with a nearly 2-fold higher risk of death without ESRD in the fully adjusted model. To our knowledge, this is the first study to link POPs contamination with ESRD and death among persons with type 2 diabetes. Previous studies showed early mortality with POPs exposure, particularly due to an increased risk of breast and pancreatic cancers [16, 17, 43].

Strengths of this study include the long follow-up time, the systematic glucose tolerance testing allowing diabetes to be diagnosed more precisely than in other populations, the wide age-range of the study population, and the large number of POPs measured. Limitations include the use of “pure” controls, which were selected to survive for at least 10 years. This selection is useful for testing the hypothesis of whether POPs exposure increases the risk of diabetes or not, but it does not allow the odds ratios to be interpreted as population estimates of incidence rate ratios. The present analysis was based on a single measurement of POPs in each participant. Subsequent changes in exposure could alter the association between POPs and incident type 2 diabetes. Frequency matching of cases and controls on 2hPG may be another limitation given that glucose levels may be a mediator between POPs and diabetes. Nevertheless, in the control group 2hPG and POP congeners were not significantly correlated, despite a broad range of POPs and 2-hour glucose concentrations. Finally, although models were adjusted for the most putative variables, other factors might influence the associations with type 2 diabetes, ESRD, or mortality; these factors remain to be defined and therefore are not adjusted for.

CONCLUSION

Most POPs were positively, but not statistically significantly associated with incident diabetes. PCB151 was significantly predictive and HCB significantly protective for diabetes. Furthermore, the study adds to previous findings showing that among persons with type 2 diabetes, PCBs with less than 4 chlorine atoms increase the risk of ESRD and death without ESRD, whereas several pesticides predict death without ESRD. Associations found between POPs exposure before development of diabetes and subsequent ESRD or death are novel. Given the extent of exposure to these toxic substances in many parts of the world, large population studies might be considered to confirm these relationships between POPs, diabetes, ESRD, and death.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggest that POPs exposure increases the risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Animal studies found a wide range of kidney tissue damage associated with POPs exposure, but this association has not been studied in humans.

What this study adds to previous knowledge is that among persons with type 2 diabetes, low-chlorine PCBs increase the risk of end-stage renal disease and death without end-stage renal disease, whereas several pesticides predict death without ESRD.

Associations found between POPs exposure before development of diabetes and subsequent ESRD or death are novel. Given the extent of exposure in many parts of the world, large population studies might be considered to confirm these relationships between POPs, diabetes, ESRD, and death.

Funding.

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and by an Inter-agency Agreement between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (09-FED-907651). The authors thank W. Turner (CDC) for the helpful discussions and assistance with the measurements of the pollutants.

Footnotes

Duality of Interest. No conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this article were presented at the 72nd Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, June 8 – 12, Philadelphia, PA 2012.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

- 1.US EPA, O. of I. and T. A. & Office of International and Tribal Affairs, U. E. Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Global Issue, A Global Response. Available: http://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/persistent-organic-pollutants-global-issue-global-response. Accessed 15 December 2015.

- 2.US EPA, O. Basic Information| Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)| US EPA. Available: http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/tsd/pcbs/pubs/about.htm. Accessed 5 January 2016.

- 3.Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC. Biomonitoring in Greenland: human biomarkers of exposure and effects - A short review. Rural Remote Health 2010; 10:1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee D-H, Lind PM, Jacobs DR Jr., et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides in plasma predict development of type 2 diabetes in the elderly: the prospective investigation of the vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:1778–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longnecker MP, Klebanoff MA, Brock JW, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl serum levels in pregnant subjects with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001; 24:1099–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriksen GL, Ketchum NS, Michalek JE, et al. Serum dioxin and diabetes mellitus in veterans of Operation Ranch Hand. Epidemiology 1997; 8:252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee D-H, Steffes MW, Sjödin A, et al. Low dose of some persistent organic pollutants predicts type 2 diabetes: a nested case-control study. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118:1235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee D-H, Lee IK, Song K, et al. A strong dose-response relation between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and diabetes: results from the National Health and Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:1638–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rignell-Hydbom A, Lidfeldt J, Kiviranta H, et al. Exposure to p,p’-DDE: a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE. 2009; 4: e7503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turyk M, Anderson H, Knobeloch L, et al. Organochlorine exposure and incidence of diabetes in a cohort of Great Lakes sport fish consumers. Environ Health Perspect 2009; 117:1076–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverstone AE, Rosenbaum PF, Weinstock RS, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure and diabetes: results from the Anniston Community Health Survey. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120:727–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor KW, Novak RF, Anderson HA, et al. Evaluation of the association between persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and diabetes in epidemiological studies: a national toxicology program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect 2013; 121:774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dirinck EL, Dirtu AC, Govindan M, et al. Exposure to persistent organic pollutants: relationship with abnormal glucose metabolism and visceral adiposity. Diabetes Care 2014; 37:1951–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee D-H, Jacobs DR Jr, Steffes M. Association of organochlorine pesticides with peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes or impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes 2008; 57:3108–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonne C, Wolkers H, Leifsson PS, et al. Organochlorine-induced histopathology in kidney and liver tissue from Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus). Chemosphere 2008; 71:1214–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee Y-M, Bae S-G, Lee S-H, et al. Associations between Cigarette Smoking and Total Mortality Differ Depending on Serum Concentrations of Persistent Organic Pollutants among the Elderly. J Korean Med Science 2013; 28:1122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong N-S, Kim K-S, Lee I-K, et al. The association between obesity and mortality in the elderly differs by serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants: a possible explanation for the obesity paradox. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36:1170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavkov ME, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, et al. Changing Patterns of Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Pima Indians. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:1758–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dabelea D, Hanson RL, Bennett PH, et al. Increasing prevalence of Type II diabetes in American Indian children. Diabetologia 1998; 41:904–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjödin A, Jones RS, Lapeza CR, et al. Semiautomated high-throughput extraction and cleanup method for the measurement of polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polybrominated biphenyls, and polychlorinated biphenyls in human serum. Anal Chem 2004; 76:1921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson DG Jr, Hampton L, Lapeza CR Jr, et al. High-resolution gas chromatographic/high-resolution mass spectrometric analysis of human serum on a whole-weight and lipid basis for 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Anal Chem 1987; 59:2000–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson DG Jr, Wong LY, Turner WE, et al. Levels in the U.S. population of those persistent organic pollutants (2003–2004) included in the Stockholm Convention or in other long range transboundary air pollution agreements. Environ Sci Technol 2009; 43:1211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass DC, Gray CN. Estimating mean exposures from censored data: exposure to benzene in the Australian petroleum industry. Ann Occup Hyg 2001; 45:275–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor JK. Quality Assurance of Chemical Measurements. (CRC Press, 1987) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison DB, Paultre F, Goran MI, Poehlman ET, Heymsfield SB. Statistical considerations regarding the use of ratios to adjust data. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:644–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schisterman EF, Whitcomb BW, Buck Louis GM, et al. Lipid Adjustment in the Analysis of Environmental Contaminants and Human Health Risks. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113:853–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol 1982; 115:92–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser HF. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1960; 20:141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergstralh E. SAS Macro That Performs Cumulative Incidence in Presence of Competing Risks. Available: http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/upload/comprisk.sas. Accessed 3 Sept 2014.

- 30.Cheng SC, Fine JB, Wei LJ. Prediction of cumulative incidence function under the proportional hazards model. Biometrics 1998; 54:219–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreiss K. Studies on populations exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. Environmental Health Perspect 1985; 60:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu H, Bertrand KA, Choi AL, et al. Persistent Organic Pollutants and Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Analysis in the Nurses’ Health Study and Meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 2013; 121:153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aminov Z, Haase R, Rej R, et al. ; Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment. Diabetes Prevalence in Relation to Serum Concentrations of Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Congener Groups and Three Chlorinated Pesticides in a Native American Population. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1376–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salihovic S, Ganna A, Fall T, et al. The metabolic fingerprint of p,p’-DDE and HCB exposure in humans. Environ Int. 2016;88:60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magliano DJ, Loh VHY, Harding JL, et al. Persistent organic pollutants and diabetes: A review of the epidemiological evidence. Diabetes & Metabolism 2014; 40:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goncharov A, Haase RF, Santiago-Rivera A, et al. , Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment. High serum PCBs are associated with elevation of serum lipids and cardiovascular disease in a Native American population. Environ Res 2008; 106:226–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grün F, Blumberg B. Perturbed nuclear receptor signaling by environmental obesogens as emerging factors in the obesity crisis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2007; 8:161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casals-Casas C, Feige JN, Desvergne B. Interference of pollutants with PPARs: endocrine disruption meets metabolism. Int J Obes 2008; 32:S53–S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rusiecki JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V, et al. Global DNA Hypomethylation Is Associated with High Serum-Persistent Organic Pollutants in Greenlandic Inuit. Environ Health Perspect 2008; 116:1547–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee DH, Jacobs DR Jr, Porta M. Hypothesis: a Unifying Mechanism for Nutrition and Chemicals as Lifelong Modulators of DNA Hypomethylation. Environ Health Perspect 2009; 117:1799–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). 2000. Toxicological profile for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JT, Kim SS, Jun DW, et al. Serum arylhydrocarbon receptor transactivating activity is elevated in type 2 diabetic patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Invest 2013; 4:483–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hardell L, Carlberg M, Hardell K, et al. Decreased survival in pancreatic cancer patients with high concentrations of organochlorines in adipose tissue. Biomed Pharmacother 2007; 61:659–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.