ABSTRACT

Increasing attention has been paid to developability assessment with the understanding that thorough evaluation of monoclonal antibody lead candidates at an early stage can avoid delays during late-stage development. The concept of developability is based on the knowledge gained from the successful development of approximately 80 marketed antibody and Fc-fusion protein drug products and from the lessons learned from many failed development programs over the last three decades. Here, we reviewed antibody quality attributes that are critical to development and traditional and state-of-the-art analytical methods to monitor those attributes. Based on our collective experiences, a practical workflow is proposed as a best practice for developability assessment including in silico evaluation, extended characterization and forced degradation using appropriate analytical methods that allow characterization with limited material consumption and fast turnaround time.

Keywords: Developability, monoclonal antibody, posttranslational modifications

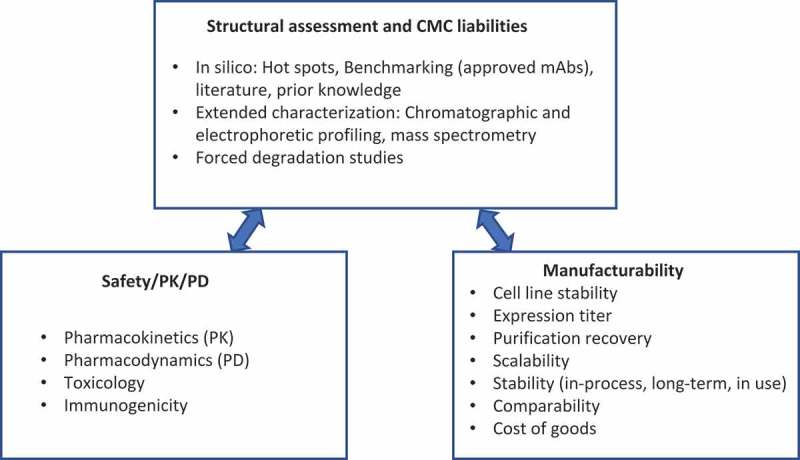

The discovery and development of monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapeutics is resource demanding and technically challenging. Specifically, challenges associated with Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) development such as high aggregation, high viscosity and susceptibility to chemical degradation and insufficient product stability have been commonly recognized. Conventionally, only limited criteria such as antigen binding and in vivo properties including safety, pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) in animal models are used to select a mAb candidate from the early discovery to development stage. Without extensive characterization to understand the biochemical and biophysical properties of the selected candidate, issues can arise from unexpected modifications, stability or poor PK and PD, which can result in delayed project progress or even termination. The development risks are often associated with the intrinsic properties of the drug candidates. Therefore, it is critical to carry out a developability assessment before entering process development. Developability assessment is a process used to systematically evaluate drug candidates, including structural assessment and CMC liabilities, safety, PK and PD, as well as manufacturability (Figure 1). Although, many interdependent factors contribute to the successful development of an mAb therapeutic, selection of a candidate with favorable biophysical and biochemical behavior help lay down a solid foundation. Thus, the primary goal of a developability assessment is to critically evaluate the biochemical and biophysical properties of mAb lead candidates and select the molecules with the lowest risks for development.

Figure 1.

Major components of mAb developability assessment.

Numerous studies have shown the importance of developability assessment of mAb lead candidates. For example, poor biophysical properties resulted in mAbs with lower expression, instability or shorter in vivo half-life.1,2 Continuous asparagine (Asn) deamidation in the complementarity-determining region (CDR) has also caused loss of potency of a mAb.3 Given the limitations of timelines and resources at the early stage of development, a thorough developability evaluation may not eliminate all risks that could occur later, but it does allow the selection of lead candidates with fewer development risks. Meanwhile, the knowledge gained through thorough evaluation also provides a strong foundation that in turn allows for a quality by design (QbD) approach for process and formulation development to mitigate any remaining identified risks. When risks are deemed critical and cannot be mitigated, an early decision to re-engineer the molecule is much more preferable than a later decision because it allows companies to save resources and avoid excessive delays of the timeline.

The biochemical and biophysical properties of mAb candidates are evaluated based on in silico and experimental evaluation, and according to: 1) the general properties of the approved mAbs; 2) scientific literature regarding the general properties of mAb molecules including posttranslational modifications (PTMs), stability and degradation pathways; and 3) drug developers’ internal knowledge from development of similar molecules.

To date, approximately 80 mAb and Fc-fusion protein drug products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA),4,5 and more than 70 are in late-stage development.6 Among them, some generally preferred drug properties for mAbs have begun to emerge (Table 1). It should be noted that some attributes such as high molecular weight (HMW) species are dependent on the sample shelf-life and handling history. MAbs with attributes within or better than these ranges are expected to have relatively lower development risks.

Table 1.

Quality attributes of a panel of FDA/EMA approved and clinical stage mAb products.

| Structural features | Ranges | References |

|---|---|---|

| Size variants | ||

| ● High molecular weight (HMW) species | <2% for most of the tested mAbs | 7 |

| ● Low molecular weight (LMW) species | <0.9% | 7 |

| Met Oxidation | 28% with oxidation in the Fab part of the heavy chain and 17% with oxidation in the light chain based on evaluation of 121 late clinical stage mAbs after treatment with 0.1% hydrogen peroxide for 24 hours | 8 |

| Charge variants | ||

| ● pI | 6.1–9.4 | 9 |

| ● Acidic | 18–60% (cIEF), 5–36% (WCX), | 9 |

| ● Main | 20–70% (cIEF), 25–92% (WCX) | 9 |

| ● Basic | 1–40% (cIEF), 3–40 % (WCX) | 9 |

| Hydrophobicity | 58% tested mAbs with low to moderate hydrophobicity | 7 |

| 33% tested mAbs with moderate to high hydrophobicity | ||

| 8% tested mAbs with very high hydrophobicity | ||

| GlycosylationMajor forms | ||

| ● G0F | 30–85% | 10–16 |

| ● G1F | 10–55% | 10–16 |

| ● G2F | 1–15% | 10–16 |

| Minor forms | ||

| ● G0, G0F-GlcNAC | <5% | 10–16 |

| ● High mannose | <15% | 10–16 |

| ● Afucosylation | <20% | 10–16 |

| ● Sialylation | <15% (up to 35% with Fab glycan) | 10,12,14–16 |

| ∘ NANA | <12% | 12,14 |

| ∘ NGNA | <2% Low (murine cell lines) | 12,15 |

| ● Alpha 1,3-gal | <3% | 10,12,13,15 |

| ● Bisecting | <5% | 10,13 |

| ● Hybrid | <10% | 12,13,15 |

Because of the highly conserved primary and similar high-order structures of mAbs, the commonly recognized degradation hot-spots can guide drug candidate evaluation to identify potential problematic features. For example, Asn and aspartate (Asp) residues in the flexible CDRs are susceptible to deamidation and isomerization,17 respectively, and thus need more careful examination. The correlation between aggregation or faster clearance and exposed hydrophobic18-22 or charged patches23,24 in the variable domains can also be applied to mAb candidate evaluation. These general principles allow identification of potential risks based on the amino acid sequences of mAb candidates.

Drug developers’ internal knowledge from process and formulation development also plays a significant role in developability evaluation. Limitations of stable cell line, cell culture media components, and drug substance process steps are common elements that may exist across the pipeline and should be part of the developability assessment consideration. Therefore, we are proposing an overall developability assessment (Figure 1), focusing on evaluation of biochemical and biophysical properties at early stage.

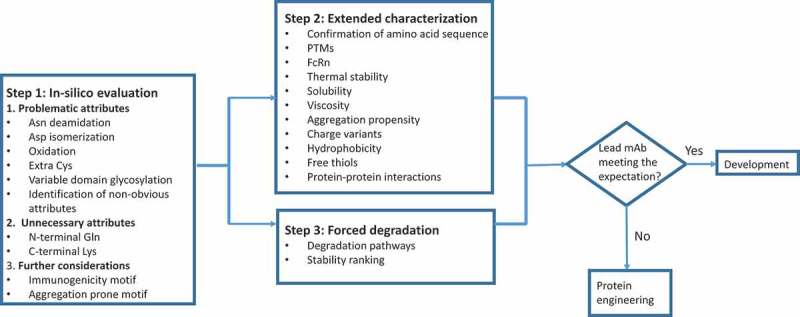

Below is a three-step workflow for the assessment of structural and CMC liabilities (Figure 2), taking into consideration previous proposals.3,25-29 Step 1 is in silico evaluation, including the use of computational methods, based on amino acid sequence to identify the known degradation hot spots and problematic motifs. Step 2 is to perform in-depth characterization to experimentally evaluate key biochemical and biophysical properties, such as structure, stability, charge profiles, PTMs, solubility, and hydrophobicity. Step 3 is to carry out limited forced degradation studies to, first, further confirm hot-spots identified from steps 1 and 2, and second, reveal candidate-specific degradation hot-spots that were not identified from Step 1. Forced degradation studies also provide additional stability information to rank the candidates. Step 2 and Step 3 can be carried out simultaneously to allow a thorough evaluation of mAb candidates within a short timeframe.

Figure 2.

Workflow of structural and CMC liabilities assessment.

In silico evaluation

We propose to categorize mAb structural features into three groups (Table 2), namely, Problematic, Unnecessary and Further Considerations for in silico evaluation, based on the general properties of mAbs, including PTMs and degradation pathways.30,31 Problematic attributes have been associated with known safety or efficacy concerns. Unnecessary attributes have not been linked to any biological functionalities. Attributes for further considerations have not been considered traditionally for mAb lead selection, but may be considered for next-generation molecules with improved properties, such as minimal immunogenicity, enhanced stability and extended half-life.

Table 2.

Categories of mAb attributes.

| Categories | Structural features | Rational |

|---|---|---|

| Problematic (Especially in CDRs) | ||

| Negatively impact safety or efficacy | ● Asn deamidation | ● Decreased affinity and immunogenicity |

| Nonhuman | ● Asp isomerization | ● Decreased affinity and immunogenicity |

| Degradation products | ● Met oxidation | ● Decreased affinity |

| ● Trp oxidation | ● Decreased affinity | |

| ● Variable domain glycosylation | ● Unpredictable impact on affinity, increased immunogenicity possibility and higher heterogeneity | |

| ● Unpaired Cys | ● Decreased affinity and stability. Increased heterogeneity | |

| Unnecessary | ||

| Causing product heterogeneity without | ● N-terminal Gln | ● Increased heterogeneity |

| impacting safety and efficacy | ● C-terminal Lys | ● Increased heterogeneity |

| Further considerations | ||

| Improving product quality | ● Immunogenicity motif | ● Immunogenicity |

| ● Aggregation prone regions | ● Aggregation and clearance | |

| ● Mutations to increase half-life | ● Patient convenience |

Problematic attributes

Problematic attributes of mAb candidates mainly encompass PTMs in CDRs that can negatively impact potency, immunogenicity and stability. MAbs are subject to PTMs and degradation during cell culture, purification, storage and even after administration. Exposure to various stress conditions during manufacturing, such as elevated temperature (e.g., cell culture, process hold steps), extreme pH (e.g., low pH protein A chromatography elution, or virus inactivation), agitation (e.g., cell culture, pumping, mixing, filtration, or shipping), shear forces (e.g.,UF/DF) and ambient light can accelerate degradation.

Asn deamidation is one of the most commonly encountered degradation pathways in mAbs, especially for Asn residues in CDRs. 17 Asn followed by the small and flexible glycine (Gly) residue (NG motif) is highly susceptible to deamidation.3,17,32-37 Additionally, protein structures can have a substantial impact on Asn deamidation, and this has been demonstrated in cases where Asn not in NG motif are susceptible to deamidation,17,37 whereas, cases where Asn in NG motif are resistant to deamidation.34,37 Asn deamidation in CDRs may cause a decrease in antigen binding affinity 33,35-37; therefore, deamidation in the CDRs continues to occur in circulation after administrated to humans,32,33 resulting in loss of potency.3 For this reason, Asn followed by Gly, and to a lesser degree, Asn followed by serine (Ser), threonine (Thr) in the CDRs, should be highlighted during in silico assessment and evaluated during extended characterization and forced degradation to confirm deamidation liability. IgG also contains susceptible deamidation sites in the so-called “PENNY” loop peptide in the Fc.38,39 Deamidation at this site continues to occur with mAbs in humans and to endogenous IgG.40 Because this region is conserved and not associated with negative impact, deamidation at this site should not be a concern for developability assessment.

Asp isomerization is another common degradation pathway for mAbs. Similar to deamidation, Asp residues in CDRs are generally prone to isomerization,17 especially when followed by a Gly residue.17,37,41-46 Isomerization of Asp followed by His42 or Ser47 have also been reported, suggesting the involvement of other factors such as residue flexibility, size and structure.17,26 Isomerization of Asp in CDRs may also cause a decrease in antigen binding affinity.37,41,42,46,48 Asp isomerization is favored around pH 5,47,49 making it challenging to formulate mAb in liquid formulation around this commonly used pH range. To reduce development risks, Asp followed by Gly, to a lesser degree, followed by Asp or His, should be highlighted during in silico evaluation and further evaluated during extended characterization and forced degradation.

Oxidation occurs frequently with methionine (Met) and tryptophan (Trp) residues. Studies demonstrated that oxidation of a Met in the heavy chain CDR2,46 as well as one in the framework region,50 did not impact antigen binding. However, a negative impact may be expected with either higher levels of oxidation or at locations that are more critical to antigen binding. Two conserved Met residues close to the CH2-CH3 domain interface and part of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), Protein A, and Protein G binding sites have been shown to be susceptible to oxidation.50-52 Oxidation of these Met residues results in decreased thermal stability,50-53 increased aggregation,51,53 decreased complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC),50 decreased binding affinity to FcRn50,54,55 and shorter in vivo half-life.56 Oxidation of Trp residues in the CDRs has been reported, which can lead to reduced potency, decreased thermal stability and increased aggregation propensity.57-59 Trp oxidation has also been shown to cause a yellow coloration to the mAb solution,60 due to the formation of kynurenine. Because higher Trp oxidation correlates with higher solvent exposure,26 Trp residues in CDRs are expected to be more susceptible to oxidation. Overall, Met and Trp in CDRs should be carefully evaluated to determine their susceptibility, and implement an appropriate control strategy during processing and formulation, if necessary.

Though rare, mAbs may have an unpaired cysteine (Cys) residue in CDRs. The unpaired Cys can be readily modified by free cysteine in cell culture medium,61,62 which has been shown to decrease antigen binding affinity.61 Candidates with unpaired Cys in the CDRs or other regions should be eliminated due to the highly reactive nature of the Cys side chain. However, the formation of a disulfide bond from two Cys residues in the heavy chain CDRs offers some unique epitope recognition properties, though no impact on stability and solubility has been observed.63

It is not uncommon for mAbs to have a consensus sequence for N-glycosylation (NXS/T, X cannot be P) in variable domains, in addition to the conserved N-glycosylation site in the Fc region. The variable domain glycosylation showed variable effects on antigen binding,64-69 but no impact for in vivo half-life.67,70 Variable domain glycosylation adds another level of uncertainty with regard to potency and comparability later in development. The higher level of terminal galactose of Fab glycosylation increases the likelihood for further galactosylation by α1,3-galactose and sialylation. Fab-associated oligosaccharides with the addition of α1,3-galactose (Gal) have been shown to cause immunogenicity.71 Sialylation could also add the immunogenic moiety of N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NGNA).12,72 It is worth mentioning that the addition of α-1,3 Gal and NGNA is highly dependent on cell line,12,13,72 and their levels should be evaluated using material from the intended stable cell line.

In silico evaluation, especially with the use of computational methods, may also assist in identifying less apparent problematic attributes. The low expression and low stability of the mAb candidate was caused by uncommon amino acids identified by statistical sequence analysis.73 Hydrophobic amino acids in CDRs were responsible for precipitation and absorption of mAb to filters during manufacturing and shorter in vivo half-life.2 Yet, another study demonstrated that asymmetric charge distribution, and to a lesser degree hydrophobicity, contributes significantly to the observed high viscosity.26 These hydrophobic or charged patches may not be obvious at the primary sequence level, but visible through proper sequence analysis and structural simulation using various computational methods. Extended characterization and forced degradation can confirm these non-obvious problematic attributes.

Unnecessary attributes

Some sequence and structural features of mAbs cause mAb heterogeneity, but not linked to any biological functions, and do not raise safety or efficacy concerns. The presence of these attributes possesses unnecessary challenges for the manufacturing of product with consistent profiles, and complicates analytical method development.

Cyclization of N-terminal glutamine (Gln) to form pyroglutamate (pyroGlu) is a major source of heterogeneity of mAbs. This reaction occurs spontaneously during drug substance production process, storage in liquid formulation and continues under physiological conditions74 and during storage. This N-terminal modification has no impact on structure, stability, or biological functions of mAbs.75 N-terminal Gln of human endogenous IgGs is almost completely converted to pyroGlu.76 It has been proposed to substitute N-terminal Gln with other amino acids to eliminate this source of heterogeneity.

Incomplete processing of C-terminal lysine (Lys) is another common modification. C-terminal Lys has no impact on mAb potency77,78 PK, PD or immunogenicity.78 However, removal of C-terminal Lys showed optimal C1q binding and CDC.79 C-terminal Lys is rapidly removed during circulation,80 explaining its absence from endogenous IgGs.80 Removal of the codon for C-terminal Lys can eliminate this heterogeneity.

Further considerations

MAbs for therapeutic purposes have evolved from murine origin, to chimeric, humanized and fully human molecules to reduce immunogenicity.81 However, immunogenicity remains a concern even for mAbs with full human sequences.81,82 Various tools including in silico calculation, in vitro assays or in vivo animal models are designed to identify amino acid sequences causing immunogenicities.81,83,84 Additional immunogenic components such as alpha 1,3 galactose can be eliminated with the removal of variable domain glycosylation sites.81,83

Aggregation of mAb therapeutics is another contributor to immunogenicity, as well as to processing difficulties.85 Attempts have been made to identify regions in mAbs that mediate aggregation through computational algorithms,18,19,86-90 or experimental screening (e.g., phage display),91 and then to improve mAb stability by mutagenesis.2,19,83,88,91,92

Host cell protein (HCP) in mAb therapeutics can also contribute to immunogenicity.93,94 The type and amount of HCP in drug substance can be dependent on the specific mAb sequence or manufacturing process conditions, such as cell line, cell culture and stringency of purification parameters. However, mAbs with more general stickiness due to exposed hydrophobic or charged patches are expected to have more HCP problems.

The potential for self-administration through subcutaneous injection requires mAbs to be formulated at high concentration (≥100 mg/mL) and delivered at small volumes (≤2mL). In terms of developability, high solubility and low viscosity are thus required. Since strong mAb self-association is often the cause of low solubility and high viscosity, protein engineering can be applied to reduce self-association by modifying the protein sequences and thus increase mAb solubility95 or decrease viscosity.26,96-99 Aside from the previously discussed potential issues with variable domain glycosylation, the introduction of glycosylation sites near aggregation-prone regions (APRs) was demonstrated to improve mAb solubility.95,100-103

Modulation of in vivo half-life has been explored by changing amino acid sequence around the FcRn binding site83,104 or in CDRs by introduction of a pH switch using histidine (His)105 or disruption of CDR positively charged patches106 Additionally, mAbs with rapid clearance due to off-target binding can be addressed by altering amino acid sequences to disrupt charged or hydrophobic patches.2,26 MAbs can be tailored to have either extended or shortened half-life to better fit their therapeutic purposes and to increase patient compliance, e.g., longer half-life reducing dosing frequency.

Experimental evaluation by extended characterization

Following in silico evaluation, lead candidates are usually evaluated experimentally through extended characterization. Quality attributes that are highly relevant to mAb developability assessment are summarized in Table 3. Usually, the initial material available for testing are produced by transient transfection (e.g., HEK293 cells). Properties that are independent of the expression hosts such as primary sequence, hydrophobicity, solubility, thermal stability, and antigen binding affinity, can be evaluated without any observable differences. On the other hand, most PTMs are highly dependent on cell line and cell culture conditions, such as pH, temperature, and cell culture duration. Those cell line-dependent attributes should be evaluated using materials produced from the stable cell lines that will be used for clinical and/or commercial manufacturing.

Table 3.

mAb quality attributes evaluated during developability assessment.

| Attributes | Objectives and objectives |

|---|---|

| Primary structure and PTMs | Determine the primary structure and PTMs. The intended primary structure needs to be confirmed. PTMs may impact efficacy and safety |

| FcRn | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on their binding affinities. Higher binding affinity correlates with longer in vivo half-life |

| Thermal stability | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on their thermal stability. Higher thermal stability correlates with lower tendency of unfolding and aggregation |

| Solubility | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on their solubility. MAbs with lower solubility pose challenges for process development, especially for high concentration formulation |

| Viscosity | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on their solubility. MAbs with higher viscosity pose challenges for process development, especially for high concentration formulation |

| Hydrophobicity | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on their hydrophobicity. MAbs with lower hydrophobicity correlate with lower tendency to aggregation, lower viscosity and higher solubility |

| Aggregation propensity | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on their aggregation propensity. Aggregates are the common product-related impurity potentially causing immunogenicity |

| Charge variants | Compare the charge profiles of mAb candidates. If no difference in safety and efficacy, it is desirable to select mAb with lower level of heterogeneity |

| Free thiols | Avoid mAbs with abnormally high level of free thiols. A high level of free thiols correlates with lower thermal stability, increased tendency to form aggregates and potentially lower antigen biding affinity. |

| Protein-protein interactions | Rank ordering mAb candidates based on self- or unspecific interactions. Strong self-interaction correlates with higher aggregation propensity, lower solubility and higher viscosity. Strong non-specific interactions may cause shorter half-life. |

Primary structure confirmation and sequence variants

The confirmation of the intended amino acid sequence is a prerequisite for further analysis and development of a mAb lead candidate. Modern mass spectrometry (MS) has the capability of accurately measuring the molecular weight of an IgG at approximately 150 kDa with the accuracy of ≤2 Da. The ability to obtain and confirm the monoisotopic molecular weights of mAbs at the subunit level provides strong evidence for confirming the primary structure.107 Ultimately, the full primary sequence can be confirmed by liquid chromatography (LC)-MS and MS/MS peptide mapping.

Several studies have shown the presence of low abundance sequence variants.108-112 Detection and identification of low levels of sequence variants are made possible by using LC-MS/MS in combination with database searches.113-115 The presence of very low abundance sequence variants is likely caused by the naturally occurring low frequency errors during transcription and translation. Selection of mAb candidates and clones with minimal sequence variants is made possible by extensive characterization.

Posttranslational modifications

LC-MS plays an essential role for developability assessment because of its high sensitivity, fast turnaround time and, most importantly, the ability to obtain an in-depth level of information. PTMs and degradation of mAb lead candidates can be obtained from LC-MS analysis at intact, subunit or peptide levels. LC-MS analysis at the intact level enables detection of modifications above its resolution and detection limit, such as glycoforms, N-terminal pyroGlu, C-terminal Lys, C-terminal amidation, and glycation. LC-MS analysis at the subunit level or after reduction into light and heavy chains localizes modifications to either the Fab, F(ab’)2, Fc regions, light chain or heavy chain.8,116,117 In addition to the traditionally used papain, more specific digestion can be achieved using limited Lys-C117,118 or Ides enzyme digestion.107,119,120 The combination of IdeS digestion and reduction decreases the molecular weight of each fragment to 23–25 kDa, allowing the measurement of monoisotopic molecular weight.107 Ultimately, analysis at the peptide level can precisely localize modification sites detected at intact and subunit levels. More importantly, analysis at the peptide level can detect modifications that cannot be detected at intact and subunit levels, such as Asn deamidation, where the molecular weight difference is about 1 Da. Because of chromatographic separation, modifications without molecular weight differences, such as Asp isomerization,41-43 L-Cys to D-Cys,121,122 and Ser racemization123 can also be detected by LC-MS.

All the reported modifications (to our best knowledge) for mAbs detected by LC-MS are listed in Table 4. Focus should be on those modifications that correspond to the potentially problematic attributes. For those PTMs that are highly dependent on cell lines, re-evaluation using materials from the stable cell line throughout the development is necessary. Comparison of the different candidates is based on the nature of modifications and their relative percentages.

Table 4.

Known PTMs of mAbs identified by LC-MS.

| Mono. mass | Ave. mass | Composition | Site/location | Modifications | Recommendation/Rationale | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + various | + various | Various amino acids | N-terminal | Partial leader sequence | Select candidates without or with low level of leader sequence because of unknown risks | 116,124-127 |

| 307.0903 | 307.26 | H(17)C(11)NO(9) | N-linked glycan | Sialylation by Neu5Gc | Select candidates with low amounts because of potential immunogenicity | 12,72 |

| 305.0681 | 305.31 | H(15)C(10)N(3)O(6)S | Cys | Glutathionylation | Select candidates without or with low amount because it indicates free cysteine/broken disulfides | 128 |

| 291.0954 | 291.26 | H(17)C(11)NO(8) | N-linked glycan | Sialylation by Neu5Ac | Not highly relevant because of low abundance, however, high levels could indicate variable domain glycosylation | 12 |

| 174.0164 | 174.11 | C(6)H(6)O(6) | N-terminal primary amine | Citric acid modification | Not highly relevant because it only occurs after long-term storage in formulation containing citric acid | 129 |

| 162.0528 | 162.14 | H(10)C(6)O(5) | Lys and N-terminal primary amine | glycation | Select candidates with low levels of glycation because it is a modification product between protein amines and reducing sugars | 130-138 |

| H(10)C(6)O(5) | N-linked glycan | Alpha 1,3-galactose | Select candidates without or with low amounts because of potential immunogenicity | 12,13,71 | ||

| H(10)C(6)O(5) | N-linked glycan | Galactosylation | Not highly relevant to manufacturability, but high levels could be due to glycosylation in variable domain. High level in Fc may correlate with higher CDC | 10,12,139 | ||

| 156.0059 | 156.09 | H(4)C(6)O(5) | N-terminal primary amine | Citric acid modification | Not highly relevant to manufacturability because it occurs after long-term storage in formulation containing citric acid | 129 |

| 148.0372 | 148.12 | H(8)C(5)O(5) | N-terminal; K | Modification by xylosone – degradation product of ascorbate – to form hemiaminal product | Selects candidates with low amounts because of uncertainty towards safety and efficacy | 140 |

| 146.0579 | 146.14 | H(10)C(6)O(4) | N-linked glycan | N-linked core fucosylation | Low fucose results in high ADCC. Highly relevant to mAb efficacy if ADCC is involved in MOA. Relevant to mAb safety if ADCC is not involved in MOA, but if the mAb recognizes cell surface target | 141-144 |

| 146.0579 | 146.14 | H(10)C(6)O(4) | S | O-linked fucosylation | Select candidates without O-linked fucosylation because of uncertainty towards safety and efficacy | 145 |

| 144.042 | 144.13 | H(10)C(6)O(4) | R | Advanced Glycation end product 3-deoxyglucosane hydroxyimidazolone | Select candidates with low amount because the presence of this indicate susceptible Arg towards glycation | 138 |

| 140.022 | 140.10 | H(4)C(5)N(2)O(3) | N-terminal; K | Modification by maleuric acid | Not highly relevant because its only present in mAb expressed from transgenic goats | 146 |

| 130.0266 | 130.10 | H(6)C(5)O(4) | N-terminal; K | Modification by xylosone – degradation product of ascorbate – to form Schiff base product | Not highly relevant due to low frequency | 140 |

| 128.0950 | 128.17 | H(12)C(6)N(2)O | C-terminal K | Addition of Lys | Mutate C-terminal Lys out to decrease heterogeneity; | 147,148 |

| Not very relevant because of lack of biological functions | ||||||

| 119.0041 | 119.14 | H(5)C(3)NO(2)S | C | Cysteinylation | Avoid candidates with extra Cys in general because modification of CDR extra Cys causes decreased affinity. Select candidates with low level of cysteinylation because of unknown risks and potential for higher heterogeneity | 61,62,149,150 |

| 79.9568 | 80.06 | O(3)S | Y | Sulfation | Not highly relevant because of low frequency of occurrence | 151 |

| 72.0211 | 72.06 | H(4)C(3)O(2) | K | Advanced glycation end product, carboxyethyllysine (CEL) | Select candidates with lower amounts because its presence indicates susceptible Arg towards glycation | 138 |

| 72.0211 | 72.06 | H(4)C(3)O(2) | R | Glycation degradation to dihydroxyimidazolidine Or direct modification by methylglyoxal in cell culture | Select candidates with low amounts because its presence indicates susceptible Arg towards glycation | 138,152 |

| 58.0055 | 58.04 | H(2)C(2)O(2) | K | Advanced glycation product, Carboxymethyllysine (CML) | Selects candidates with low amounts because its presence indicates susceptible Lys towards glycation, advanced glycation end product | 138 |

| 56.0262 | 56.06 | H(4)C(3)O | N-terminal; K | Modified by citric acid photo degradation product | Not highly relevant because it occurs under harsh conditions in formulation buffers containing citric acid | 153 |

| 54.0106 | 54.05 | H(2)C(3)O | R | Advanced end Glycation degradation product-methyl glyoxal hydroimidazolone or direct modification by methylglyoxal in cell culture | Select candidates with low amounts because its presence indicates susceptible Arg towards glycation | 138,152 |

| 47.9847 | 48.00 | O(3) | C | Oxidation of Cys to form sulfonic acid | Not highly relevant because of low frequency of occurrence | 150 |

| 38.0156 | 38.048 | H2C3 | N-terminal | Modified by citric acid photodegradation product | Not highly relevant because it occurs under harsh conditions in formulation buffers containing citric acid | 153 |

| 37.979 | 38.00 | C(2)H(−2)O(1) | R | Arg modification to form glyoxal hydroxyimidazolone | Select candidates with low amounts because its presence indicates susceptible Arg towards glycation | 138 |

| 31.9898 | 32.00 | O(2) | M | Double oxidation to form methionine sulfone | Not highly relevant because of low frequency of occurrence under very harsh condition | 138 |

| O(2) | W | Oxidation to N-formylkynurenine | Select candidates with low amounts because presence of this modification indicates Trp susceptibility | 60 | ||

| 31.9721 | 32.06 | S | C | Trisulfide | Select candidates with low amounts because its degradation product with unknown risks | 154,155 |

| O(2) | C | Oxidation of Cys to form sulfinic acid | Not highly relevant because of low frequency of occurrence | 150 | ||

| 19.9898 | 19.99 | C(−1)O(2) | W | Oxidation to 3-hydroxykynurenine | Select candidates with low amounts because presence of this modification indicates Trp susceptibility | 60 |

| 15.9949 | 16.00 | O | M | Oxidation to methionine sulfoxide | Select candidates with low amounts because Met oxidation may cause decreased affinity when in CDRs and decreased binding to FcRn and shorter half-life when in the constant domains | 50,54,55,138,156 |

| O | K | hydroxylysine | Not highly relevant because of low frequency | 157 | ||

| O | W | Oxidized to hydroxytryptophan | Select candidates with low amounts because the presence of this modification indicates Trp susceptibility | 57,59,60,138,158 | ||

| O | P | Oxidative carbonylation to glutamic semialdehyde | Not highly relevant because it of low frequency | 159 | ||

| 13.9792 | 13.98 | H(−2)O | H | His-His cross-linking | Not highly relevant unless the candidates are extremely sensitive to light | 160 |

| 3.9949 | 3.99 | C(−1)O | W | Oxidation to kynurenine | Select candidates with low amounts because the presence of this modification indicates Trp susceptibility | 60,138 |

| 2.0157 | 2.02 | H(2) | C | Incomplete disulfide bonds | Select candidates without or with low amounts of this modification because it decreased antigen affinity when in CDRs and stability when in other domains. | 161–163 |

| 0.9840 | 0.98 | H(−1)N(−1)O | N | deamidation | Select candidates with low amount of this modification because deamidation decreases potency when in CDRs and in general causes potential immunogenicity heterogeneity | 33,36-39,49,75,164,165 |

| 0 | 0 | - | D | Asp isomerization | Select candidates with low amount because isomerization decreases affinity when in CDR and the formation of isoAsp causes concerns for immunogenicity | 41-43 |

| - | C | Racemization | Not very relevant because of low frequency | 121,122 | ||

| - | S | Racemization | Not very relevant because of low frequency | 123 | ||

| −1.0316 | −1.03 | H(−3)N(−1)O | K | Oxidative carbonylation to aminoadipic semialdehyde | Not highly relevant because of low frequency | 159 |

| −2.0157 | −2.02 | H(−2) | W | Trp oxidation product | Not very relevant because of low frequency | 59 |

| H(−2) | T | Oxidative carbonylation to keto-threonine | Not very relevant because of low frequency | 159 | ||

| −17.0265 | −17.03 | H(−3)N(−1) | Q | Pyro-Glu | Mutate N-terminal Gln to lower heterogeneity. If present, it has no impact except causing heterogeneity | 74,75,162,166 |

| H(−3)N(−1) | N | Succinimide as Asn deamidation intermediate | Select candidates without or with low amount of succinimide because it indicates the presence of susceptible deamidation sites | 49,167 | ||

| −18.0106 | 18.02 | H(−2)O(−1) | E | Pyro-E | Not highly relevant because of lower rate of conversion | 168,169 |

| H(−2)O(−1) | D | Succinimide as Asp isomerization intermediate | Select candidates without or with low amount of succinimide because it indicates the presence of susceptible deamidation sites | 41,43,47,48,170-172 | ||

| −31.9721 | −32.06 | S(−1) | C | Thioether | Select candidates with low amount of thioether because its presence indicates disulfide bond degradation | 173,174 |

| −33.9877 | −34.08 | H(−2)S(−1) | C | Dehydroalanine | Not highly relevant because it of low frequency | 173 |

| −43.0534 | −43.07 | H(−5)N(−3)C(−1)O | R | Oxidative carbonylation to glutamic semialdehyde | Not highly relevant because it of low frequency | 159 |

| −58.0055 | −58.04 | H(−2)C(−2)O(−2) | C-terminal P | C-terminal amidation | Not highly relevant because of low frequency | 175,176 |

| −203.0793 | −203.20 | H(−13)C(−8)N(−1)O(−5) | N-linked glycan | Loss of N-acetylglucosamine | Select candidates with low amount because it indicates incomplete glycan processing or degradation | 10,177-184 |

Modifications with safety or efficacy concerns

This group of modifications are known to be linked with safety and efficacy issues. These modifications correspond to Problematic attributes listed in Table 2, which includes deamidation, isomerization, Met and Trp oxidation, unpaired cysteine and additional glycosylation in the variable domains. This group of modifications should be carefully examined during extended characterization and forced degradation studies.

There are three types of oligosaccharides, α1,3-Gal, NGNA and high mannose, that should be evaluated carefully. As discussed previously, α1,3-Gal and NGNA are immunogenic. High mannose has been shown to cause shorter in vivo half-life185-191 and enhanced antibody-dependent cell-meditated cytotoxicity (ADCC) due to the lack of core-fucose.187,190,191 Additionally, the afucosylation level must be monitored because of its correlation with enhanced ADCC,141 which could be either beneficial or harmful depending on the mAb’s mechanism of action (MOA).192 Higher levels of afucosylation are beneficial for mAbs targeting cell surface antigen and initiating cell killing, while it is harmful for mAbs that only block cell surface antigens. The levels of those oligosaccharides should be re-evaluated using material generated from the stable cell lines that will be used for clinical and commercial production.

Modifications corresponding to degradation

This group of modifications has not been reported to impact product safety or efficacy, but could potentially cause immunogenicity because these modifications are not present in either human endogenous IgG or degradation products. This group of modifications includes the presence of partial leader sequence, trisulfide bond, thioether, and glycation. To minimize this risk, mAb lead candidates with the lowest levels of these types of modification should be selected. Modifications in this category may also be highly dependent on cell lines and cell culture parameters such as temperature, pH, media composition and formulation.

Modifications causing heterogeneity

N-terminal pyroGlu formation and partial removal of C-terminal Lys are two of the well characterized modifications that cause molecule heterogeneity, but have no impact on safety or efficacy. Additionally, the levels of these modifications are highly dependent on cell line and cell culture conditions.

The level of terminal Gal associated with the glycosylation of Fc is also of note due to its sensitivity to process changes. The terminal Gal has no impact on structure,179-181,193,194 stability 184,195 or clearance.70,185,186,189,196,197 Recent studies have demonstrated that the terminal galactose may have minimal impact on ADCC, but substantial influence on CDC.139,198 Therefore, the level of terminal galactose should be considered for mAb candidates with MOA involving CDC. Since the level of terminal galactosylation varies with different cell lines and cell culture conditions, it may have to be re-evaluated later in the development process.

FcRn affinity

FcRn binding is one of the most critical factors affecting mAb half-life.104 The FcRn binding affinities of mAb candidates are usually measured by Biacore, but alternative assays using biolayer interferometry (BLI) or FcRn affinity chromatography have been established. In a study evaluating mAbs, it was found that delayed elution of mAbs from an FcRn affinity column at neutral pH correlated with poor pK.24,199 Compared to Biacore and affinity chromatography, much higher throughput can be obtained using BLI.200 In general, mAbs with stronger FcRn binding at acidic pH, but fast dissociation at neutral pH, show longer in vivo half-life.104

Thermal stability

Thermal stability is the ability of a protein to maintain its structural and functional integrity under different temperature environment, and is an intrinsic property of mAbs that can influence product stability, such as aggregation, during manufacturing and storage. High thermal stability of a mAb candidate indicates a well-packed structure that requires more energy to unfold. Therefore, higher thermal stability of a mAb generally correlates with a lower tendency towards partial unfolding and thus aggregation.19,73,201-206 Besides aggregation, mAbs with lower thermal stability have been shown to have lower expression.73,207

Thermal stability has been commonly measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). 19,73,201-206 An alternative method using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) allows high throughput thermal stability screening of 96 or 384 samples.202,206,208-210 Multiple candidates analyzed under the same conditions can be ranked based on the obtained thermodynamic parameters such as the midpoint temperature (Tm) of unfolding or the onset of unfolding temperature (Tonset).

Solubility

Solubility is an important developability parameter for mAbs,211,212 especially in consideration of the industry trend towards higher concentration formulations (100 mg/mL and above).213 MAbs must remain soluble throughout processing, storage and administration.97,211 Low solubility can lead to issues during purification, sterile filtration, fill and finish, shipping, storage214 and more importantly, can adversely affect activity, bioavailability, and immunogenicity.212,215 From the process perspective, a minimum solubility (e.g., 20–30 mg/mL) in the buffers used for bioprocessing is necessary for all the chromatographic steps. During the final ultrafiltration/diafiltration (UF/DF) step, mAbs are buffer exchanged into formulation buffers at concentrations above the targeted drug product, thus requiring much higher solubility.

Lower solubility is usually caused by strong mAb self- association with exposed hydrophobic or charged patches. Naturally, the bivalent nature of mAbs amplifies their self-association tendencies.216 Colloidal instability caused by conformational changes or chemical modifications can also contribute to the poor solubility of a mAb. Additionally, mAb solubility is often influenced by solution properties, such as buffer composition, ionic strength, pH, and temperature.214,217-219

It is challenging to predict solubility of mAb candidates based on the amino acid sequences, therefore solubility of mAbs should be studied experimentally. However, studying mAb solubility directly requires large amounts of protein, typically several hundred milligrams, and it is often not practical to produce all candidates at such large quantities for solubility study. Given the limited sample quantities available for developability assessment studies, indirect measurement methods are commonly used. For example, addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to mAb solutions causes precipitation at much lower concentrations, and thus can be used to determine the apparent solubility of mAbs through extrapolation to zero PEG concentration.212,220-222 This approach can be implemented in a high-throughput manner for mAb candidate selection. However, PEG-induced precipitation may not truly reflect the mechanisms of the poor solubility of mAbs,218,223 and thus orthogonal methods or direct evaluation of solubility at high concentration should be considered to confirm the predicted solubility or validate the rank order.

Prediction of the high concentration behavior of a mAb using low concentration sample may also be done through the measurement of the osmotic second virial coefficient B22, a thermodynamic parameter related to intermolecular interactions. Positive and negative B22 values indicate repulsive or attractive forces, respectively. Parameters affecting B22 include electrostatic interactions, van der Waals force, excluded volumes, hydration forces, and hydrophobic effects.224,225 Among many different ways to obtain B22 values, such as self-interaction chromatography (SIC),226 membrane osmometry (MO)227 and analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC),228 the most common method is through static light scattering (SLS).225,229,230 Recently this value was used to determine a universal solubility line, the “liquidus” line, as part of a phase diagram for a mAb.231,232

Cross-interaction chromatography (CIC) assay, introduced by Jacob et al.233 takes advantage of the accumulative effect on a column to capture weak binding between testing mAb and a large quantity (30 mgs) of immobilized human serum IgGs. MAbs with late elution by CIC assay correlate with poor solubility, due to exposed sticky (hydrophobic or charge) surfaces. The other method worth mentioning is self-interaction nanoparticle spectroscopy, which uses gold nanoparticles to concentrate mAb molecule to a high local concentration to amplify weak self-interaction.216,234 This method can also be applied to high throughput screening of mAb candidates.234

Viscosity

High concentration drug products administrated via subcutaneous (SC) injection require a formulation with manageable viscosity, making it another critical factor for evaluation at an early stage to ease developability concerns.235 High viscosity can pose challenges to the final UF/DF step 28,236,237 and fill/finish operation.238,239 Viscous drug product can lead to difficulties in delivery causing low patient compliance.240 Viscous samples can also pose sampling challenges for analytical method development and instrumentation.241

High viscosity has been shown to be caused by strong mAb self-association through electrostatic 26,98,242-246 or hydrophobic interactions,26,242 or the combination of both.26,242,247 Although, a number of formulation parameters, including pH, salts, sugars, and various small molecule excipients and detergents can be explored to lower viscocity,97,248-251 selection of mAb lead candidates with minimal inherent problems such as exposure of hydrophobic, or charged patches is one of the most efficient means to minimize high viscosity risk.242,252

A variety of methods have been used to measure viscosity, including Cannon-Fenske Routine viscometer, Taylor Cone plate method, and various rheometers. Most of the conventional techniques for measuring viscosity require a large amount of materials. To overcome this challenge, in particular for developability assessment, a high throughput DLS method has been developed based on measurement of apparent polystyrene bead radii in high concentration mAb solutions to back calculate the viscosity of a mAb solution.253 This method can only be used for mAbs without interaction with the beads, otherwise the apparent bead radii cannot be reliably measured. High throughput diffusion interaction parameters derived from DLS measurement have also been shown to correlate with viscosity.254 In recent years, the instruments allowing viscosity measurement using ≤100 µL and with automated sample handling have become commercially available, and these are suitable for measuring viscosity during developability assessment.

Because of the significance of viscosity for process and product development, having a carefully defined viscosity target for developability assessment is important. At minimum, the formulation viscosity should be low enough to allow the drug formulation to be delivered with manual injection. The viscosity target is typically developed based on each company’s internal development experience, in particular for developing SC product with prefilled syringes and auto-injector devices. For example, it was proposed that the viscosity can be grouped into 3 categories: 1) “preferred” viscosity of 10 cP or lower; 2) “acceptable” viscosity between 10 to 20 cP; and 3) “unacceptable’ viscosity of > 20 cP. This can be used as a starting point for defining the viscosity target with additional considerations of the internal experience of process and product development and product knowledge of delivery devices, such as autoinjector.

Aggregation propensity

Aggregates are the most commonly observed product-related impurities, requiring close monitoring due to immunogenicity concerns.85,255 Therefore, it is a critical component of developability assessment. In addition to utilizing predictive tools, aggregation propensity can be directly measured during extended characterization and forced degradation studies. Though typically only low concentration data is available due to material limitation, it is important to evaluate the colloidal stability and aggregation propensity of a mAb at medium to high (50–100 mg/mL) concentration ranges.

Routinely, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) or capillary electrophoresis (CE-SDS) are used to determine mAb monomer, fragments and covalent aggregates under denaturing conditions with or without reduction. A variety of other methods are available to measure mAb soluble aggregates such as dimer, oligomer or subvisible particles under native conditions.255-258 Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is the most commonly used method to determine mAb HMW species (e.g., dimer, trimer or oligomers) and LMW species. SEC is typically included for product release and often available as a generic or platform method, therefore it is suitable for evaluation of aggregates during extended characterization and forced degradation. It is worth mentioning that SEC can sometimes reveal properties other than the percentage of monomer, aggregates and fragments. Abnormal SEC behaviors of a mAb, such as peak tailing, could indicate non-ideal biophysical properties.1 Longer retention time and asymmetric peak shape can suggest nonspecific interactions between a mAb and the SEC column.2 Studies showed that SEC can even separate mAb variants containing succinimide intermediate from those with Asn deamidation (17Da) or Asp isomerization (18Da).167,259 SEC has also shown that a mAb variant containing oxidized Trp eluting earlier than the main peak.158 These examples suggest that interpretation of SEC data should be done cautiously because earlier and later peaks may not always represent HMW or LMW species.

For large aggregates, light scattering can be used to characterize particles in the range of <1 nm to 1–10 µm. The DLS method can be used to determine the hydrodynamic diameters of mAbs242 and interaction parameters, such as KD,260,261 which can be run in high throughput mode with low sample consumption. Methods that measure turbidity, such as optical density at visible wavelength and nephelometry, can also be considered for detection of submicron/sub visible particles. These techniques may be developed with high throughout and low volume consumption, and thus can be used for developability assessment. Light obscuration (e.g., HIAC) and flow imaging methods (e.g., micro-flow imaging (MFI)) and FlowCam) can be used for sub-visible particle characterization and quantification for sizes greater than 2 µm. A visual inspection method is used for detecting the protein particles in the visible range, typically > 70 to 100 µm.

In addition to directly measuring the level of aggregates, aggregation propensity can be ranked based on hydrophobicity or protein interactions as they are the main driving forces for aggregation. Fluorescence dyes such as 1-anilino-naphthalenesulfonate (ANS) and thioflavin can be used to probe exposed hydrophobic patches in a high throughput manner with minimal sample requirement.262 Affinity capture self-interaction nanoparticle spectroscopy (AC-SINS), which provides coarse-grained information about interactions and aggregation propensity in different solution conditions, is useful to leverage during developability evaluations.234

Charge variants

Charge variation of mAbs reflects the sum of various PTMs. Variants of mAbs need to be closely monitored throughout the development process to ensure consistent peak profiles. Because of its sensitivity to process changes, charge variation is one of the quality attributes that could be challenging for demonstrating comparability, when process changes are introduced.

A typical mAb charge variant profile characterized by charged-based methods such as ion exchange chromatography and isoelectric focusing usually contains one major peak and several smaller acidic and basic peaks. Reported modifications resulting in the formation of acidic or basic species are shown in Table 5. It is worth mentioning that several modifications may impact chromatographic separations of mAb variants by modulating mAb structures. For examples, mAbs with smaller oligosaccharides can contribute to the formation of basic species,263 while the oxidized Met may contribute to the formation of either acidic172,264 or basic265,266 species. Similarly, the presence of the incompletely formed disulfide bond in the heavy chain variable domain can either contribute to acidic163 or basic162 species.

Table 5.

Modifications that form either acidic or basic species.

| Modifications | References |

|---|---|

| Acidic | |

| ● Deamidation | 33,36,37,75,116,126,264,267-270 |

| ● Glycation | 126,130 |

| ● Sialic acid | 75,126,271-273 |

| ● Incomplete disulfide bond | 163 |

| ● Tyrosine sulfation | 151 |

| ● Trisulfide bond | 155 |

| ● IgG2A/B and IgG2B | 256 |

| ● O-fucosylation | 145 |

| ● Modification by maleuric acid | 146 |

| ● Modification by methylglyoxal | 152 |

| ● Cysteinylation | 61 |

| ● Methionine oxidation | 172,264 |

| ● Asp isomerization intermediate succinimide | 274 |

| ● Leader sequence | 275 |

| ● Asp isomerization | 116 |

| Basic | |

| ● C-terminal Lys | 75,77,126,127,166 |

| ● N-terminal remaining Gln | 75,127,162,166 |

| ● Succinimide intermediate from Asp | 37,43,47,49 |

| ● C-teminal amidation | 116,124,175 |

| ● Asp isomerization | 37,274 |

| ● Leader sequence | 75,116,126,127 |

| ● Incomplete disulfide bond | 162 |

| ● Met oxidation | 265,266 |

| ● Smaller oligosaccharides | 263 |

| ● Cysteinylation | 275 |

Isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis (IEF) was traditionally used to analyze mAb charge variants.37,267,268,276 This semi-quantitative, labor-intensive method relies on dye staining for detection. It also suffers from low throughput, lack of automation and poor reproducibility. Capillary IEF (cIEF) overcame most of the IEF limitations and offered additional advantages, including high sensitivity, automation, and low sample consumption.276-278 Moreover, imaged cIEF (icIEF) has gained popularity for the analysis of mAb charge variants279-281 because the whole capillary imaging eliminates the troublesome mobilization step used by cIEF.282

Capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE) separates mAb charge variants based on both charge and hydrodynamic radius. This method can be readily platformed with relatively high throughput compared to cIEF.277,278,283-286 CZE can also be coupled on-line with a mass spectrometer. CZE-MS has been used to profile N-linked glycans from tryptic peptides16 and analyze the sites of deamidation and isomerization.287 A single CE-MS run has been shown to confirm 100% of the primary structure and reveal several PTMs, including glycosylation, N-terminal Gln cyclization, deamidation and isomerization.288

Ion exchange chromatography (IEX), including cation exchange36,37,75,166,264,267,268,271,272 and anion exchange,116,155,276 has been widely used to monitor mAb charge variants. IEX allows fraction collection for further characterization. Multiple mAbs can be analyzed when a pH gradient is used,289 implying the potential for establishment of a platform method. Strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography allows a relatively higher throughput compared to weak cation exchange chromatography.290,291 When comparing the overall charge profiles, IEF usually shows comparable results with either cation37or anion276 exchange chromatography. However, different profiles have been observed due to differences in the separation mechanisms.267,268

Hydrophobicity and related heterogeneity

Hydrophobicity can impact mAb aggregation, solubility and viscosity.292,293 Higher hydrophobicity correlates with higher propensity towards aggregation18,19,21,22 and precipitation.293,294 Hydrophobic patches in CDRs can lead to a higher degree of inter-molecule interaction, higher viscosity and shorter in vivo half-life.2,26

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) has been used to measure the relative hydrophobicity of different mAbs7,25,292 or separate variants of the same mAb caused by PTMs or degradation.37,41,43,161 Reported modifications causing HIC retention time shift, as compared to the main peak, are listed in Table 6. Some modifications such as Asp isomerization and deamidation can shift HIC retention times both ways, suggesting the involvement of other factors impacting chromatographic behavior.

Table 6.

Modifications causing HIC retention time shift.

| Modifications | References |

|---|---|

| Early shift | |

| ● C-terminal Lys | 41,172 |

| ● Deamidation | 37,270 |

| ● Asp isomerization | 37,172 |

| ● Met oxidation | 156,161,172,296 |

| ● Trp oxidation | 296 |

| ● Fragments | 172 |

| ● O-fucosylation | 145 |

| ● Fab N-glycosylation | 20 |

| ● Isomerization succinimide | 43 |

| ● Cysteinylation | 150 |

| Late shift | |

| ● Asp isomerization | 41,43,44,161 |

| ● Variable domain incomplete disulfide bond | 43,44,161,297 |

| ● Succinimide as isomerization and deamidation intermediate | 37,41,43,44,161,167,172 |

| ● Aggregates | 172 |

Alternative methods for measuring mAb relative hydrophobicity of mAbs have also been reported, such as the use of gold nanoparticle via salt gradient screening.295 In this method, the testing mAb is loaded onto gold nanoparticles, followed by salt gradient stress to strip water molecules from hydrophobic patches on the surface of a mAb molecule. The results demonstrated a good correlation with HIC retention times for tested mAbs.

Free thiols

The presence of significant levels of free Cys negatively impacts mAb stability and potency. The level of free Cys and free Cys-related modifications and degradations are highly dependent on mAb sequence, as well as environmental factors during cell culture and purification.

MAbs contain low levels of free thiols at each Cys residue.298-300 Free thiols have been shown to lower thermal stability298 and increase formation of reducible covalent aggregates.301,302 These mAb-associated free cysteines can react with free cysteine present in cell culture media to form cysteinylated or other covalent adducts.61,62,128,149,150 In a few cases, relatively higher levels of free cysteine were detected, mainly due to incomplete formation of heavy chain variable domain disulfide bonds,161-163 which could result in reduced potency.161

Protein-protein interactions

Protein-protein interaction has drawn increasing attention during developability evaluation due to its impact on solubility, viscosity, and aggregation propensity96,254,294,303-305 In addition, non-specific off-target binding in vivo resulted in fast clearance and poor PK23,306

A variety of techniques have been developed to study protein-protein interactions for mAbs, including self-interactions and non-specific interactions with other molecules. Among these techniques, Biacore,307 bio-layer interferometry (BLI),308 and self-interaction nanoparticle spectroscopy (SINS).216,234,309,310 have been used to study self-interaction. On the other hand, cross-interaction chromatography (CIC) can be used to study non-specific interaction when different proteins were immobilized.233,293,311 Positive correlation between delayed retention between CIC and HIC suggests that hydrophobic interaction being a major contributing factor to the general stickiness (non-specific interaction) of these mAbs.293 Other assays including the polyspecificity reagent binding assay,312 and binding to heparin,313 HEK293 cells,106 baculovirus particles,314 chaperone proteins,315 and yeast316 have also been used to study non-specific interactions.

Experimental evaluation by forced degradation

Forced degradation studies are playing an ever-increasing role providing critical information to support mAb drug development.31 Forced degradation studies can be predictive of in vivo degradation3,33,35,40 and can also be used to validate liable spots identified from in silico evaluation, reveal degradation hot-spots that are not obvious from in-silico and provide a ranking order of mAb candidates based on stability. The commonly used forced degradation conditions and major degradation pathways, and recommendations to support developability are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Forced degradation conditions, degradation pathways, and recommendations for developability evaluation.

| Conditions | Objective | Degradation pathways and impact | Whether or not to include in developability assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal | To accelerate degradation and increase detectability of degradants | Aggregation132,164,317327 | Include |

| Fragmentation164,317,320,324-326,328-333 | Thermal stress is the most relevant condition to product development because high temperature is the common stress encountered during processing, stability and in vivo. Thermal stress can accelerate degradation and thus increases the detectability of potential degradation pathways | ||

| Asn deamidation 3,33,49,164,324,334,335 | |||

| Cyclization of N-terminal Glu164 | |||

| Met oxidation156,324 | |||

| Asp isomerization41,47,48,170,171 | |||

| Disulfide bond degradation through β-elimination322,323,333 | |||

| High pH | To probe for liable deamidation sites | Asn deamidation267,276,322 | Include |

| Aggregation322,323 | Deamidation is one of the most commonly observed modifications that can cause loss of potency and potentially immunogenicity | ||

| Fragmentation322,328,332,336,337 Disulfide bonds | |||

| degradation322,337 | |||

| Oxidation | To probe for liable oxidation sites | Met oxidation8,54-56,324 | Optional |

| Trp oxidation60 | Oxidation is one of the most commonly observed modifications that can cause loss of potency directly or indirectly by shortening half-life. However, highly susceptible residues are detectable during extended characterization or thermal stress. | ||

| Aggregation323 | |||

| Low pH | To determine low pH susceptibility towards aggregation, fragmentation, and increase detectability of succinimide from Asp isomerization | Aggregation322,336,338,339 | Optional |

| Fragmentation330,332,333,337 | Low pH conditions can be encountered during purification such as protein A chromatography elution and low pH virus inactivation. | ||

| Accumulation of succinimide intermediate41-43,170,171,259 | |||

| Agitation | To determine susceptibility towards aggregation | Aggregation301,319,323,336,340-344 | Do not include |

| Met oxidation324 | Agitation is a common stress during cell culture, purification and shipping. However, agitation may not be a major concern of causing stability issues for mAb in general, unless, there are reasons to suspect a particular mAb is sensitive to agitation. | ||

| Trp oxidation324 | |||

| Freeze/thaw | To determine feasibility of freezing | Aggregation and precipitation321,325,327,336,345 | Do not include |

| Freeze/thaw is stress only when mAbs are stored or shipped under frozen condition. This condition is only included when exploring the option of frozen drug substance. | |||

| Light | To determine photo-catalyzed degradation mainly oxidation and cross-linking | Trp oxidation58,59,346,347 | Do not include |

| Met oxidation58,59,156,346,348 | Generally, light sensitivity is not a common concern unless there are Trp residues in CDRs | ||

| Histidine (His) oxidation58 | |||

| Aggregation58,346 | |||

| Fragmentation58,346 | |||

| Asn deamidation58 | |||

| Covalent cross-linking160,346 |

Forced degradation studies are important for confirmation3 or rejection 34 of the predicted degradation hot-spots from in silico assessment. More importantly, forced degradation studies can reveal the hidden degradation hot-spots that are not generally recognized or specific to individual mAb lead candidates. The relatively harsh conditions used in forced degradation studies can increase the detectability of degradation products that are normally present at low levels during extended characterization. For example, susceptibility of Asp to isomerization and peptide bond hydrolysis in an Asp-Asp motif in the CDR315 or susceptibility of a Ser-Ser motif in the CDR to peptide bond hydrolysis 316 can only be detected during forced degradation.

Forced degradation studies are valuable for defining process parameters and for prediction of long-term stability.317 Low pH is a common stress during protein A chromatography elution and virus inactivation steps used for a typical mAb purification process. MAb candidates with poor low pH stability will require extensive efforts using alternative purification and virus inactivation processes. MAbs could also be transiently exposed to high pH conditions during anion exchange chromatography elution and pH neutralization after low pH exposure. MAbs that are sensitive to agitation, light, freeze/thaw cycle can be a challenge to the establishment of a robust process due to limited design space.

Forced degradation results for any given mAb are highly dependent on the selected conditions. It is well known that the first and second Asn residues in the “PENNY” peptide are highly susceptible to deamidation.38,39 However, the Asn residue within the amino acid sequence VSNK was found to have an even higher level of deamidation compared to the “PENNY” peptides when stored at pH 5.2.169 Specific guidance regarding photostability is provided in ICH Q1B, but the recommended conditions are different from room light conditions.349 From the developability assessment perspective, forced degradation conditions may be best selected based on their relevance to process, stability and in vivo conditions, while taking into consideration the intrinsic properties of the mAb candidates.

Computational tools

Computational approaches are attractive for mAb developability assessment as the amino acid sequence is the only necessary input. Thus, they can be applied to in-silico evaluation for in-depth evaluation, in addition to identifying the obvious degradation hot-spots. Potential problematic attributes from known motifs or the presence of less frequently observed amino acid at certain positions can be easily highlighted.73,84,90 Several computational tools, based on machine learning, are available to calculate the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA).350 SASA showed good predictability of the chemical liability, such as oxidation of Met8 and Trp26 or Asp isomerization,26 as well as HIC retention times.350

Computational tools are also available to rank viscosity of mAb lead candidates based on the known amino acid sequences. The variable domain net charge, asymmetric charge distribution and, to a lesser degree hydrophobicity, were found to contribute to higher viscosity.26 The spatial charge map was established based on amino acid sequence and homology modeling to predict viscosity.351 Calculation of biochemical and biophysical properties based on homology modeling of variable regions of low and high viscosity mAbs revealed that net negative charge, zeta-potential and variable domain isoelectric point are the critical parameters impacting viscosity.245 Homology modeling has identified surface negatively charged patches causing high viscosity.99 Interestingly, homology modeling also identified positively charged patches in the variable domain of a mAb responsible for its shorter half-life, which was related to decreased dissociation from FcRn at neutral pH.24 Coarse-grained modeling has also been used to understand inter-molecule interactions, and has revealed that domain-level electrostatic interactions play an important role.349,352,353

Various computational tools have also been developed to identify structural features that could trigger aggregation.86,87 Spatial-aggregation-propensity (SAP), based on molecular simulation, can be used to identify aggregation-prone motifs, due to formation of hydrophobic patches in the tertiary structure.18,19,89,294 Mutation of the identified hydrophobic residues to hydrophilic ones has been shown to increase stability.18,19,294 SAP identified APRs in the constant domains,18 as well as in variable domains,90 highlighting the need to balance the affinity and aggregation propensity. Lauer et al proposed the concept of a developability index, to rank mAbs based on aggregation propensity calculated from the net charge and SAP of the CDRs.27 Based on experimental data from over 500 mAbs, a model was built using statistical modeling and machine learning to categorize mAbs to high or low risk towards aggregation.354

Computational tools have also been developed to identify unwanted in vivo behaviors such as poor PK29 and immunogeneicity.355 Studies have shown that faster mAb clearance correlated with exposed hydrophobic or charged patches in the variable domains.26,356 T-cell epitopes can be identified by computational tools,355 which can be used to rank mAb candidates to lower the potential immunogenicity risk.

Emerging analytical methods

Emerging analytical methods may have the potential to gather information faster with less material consumption, and thus can be applied to mAb developability assessment. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) has been applied to mAb characterization.357,358 With a polar stationary phase and an organic mobile phase, HILIC is fully compatible with MS and offers a complementary retention mechanism compared to reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). This chromatographic method was mostly used for released glycan profiling and glycopeptide separations. It can also be used as an orthogonal method to RP-HPLC at the subunit level following IdeS digestion.

Two-dimensional LC (2D-LC) with MS and other detection methods (e.g., UV) clearly facilitate a deep structural understanding of mAbs.359-361 The additional chromatographic selectivity and resolution of 2D-LC compared to the conventional 1D-LC methods enables the direct and efficient identification of different variants present in these materials. 2D-LC with various combinations, such as SEC×RP–MS, CEX×RP–MS, and HIC×RP–MS, have the potential to provide extensive characterization of mAbs with automation and low material consumption to support developability evaluation.

Recommendations

Acceleration of development activities to bring mAb drug candidates into first-in-human clinical studies, and then to market is the ultimate goal of drug developers. There is a fine balance between minimizing the risks at early stages and accelerating the later stages of development to provide the essential therapies to patients. It is not practical, nor necessary, to apply all of the discussed methods and studies for a developability evaluation.

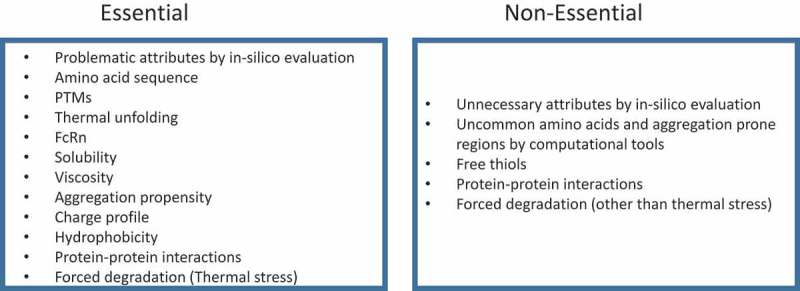

We propose a workflow as outlined in Figure 3, which categorizes studies and testing as “Essential”, which must be included, or “Non-essential”, which are optional. The goal of this workflow is to gather scientific information and experimental data within a reasonable timeframe for candidate ranking and selection.

Figure 3.

Recommended attributes for developability assessment.

It is worth mentioning that ex vivo and in vivo serum stability has gained popularity because of the relevance to physiological conditions. Those studies can be considered under specific occasions in order to ease the remaining concerns of the selected mAb candidates. For example, in the case of incomplete heavy chain variable domain disulfide bond formation, additional studies demonstrated that they can be formed rapidly under ex vivo and in vivo conditions, thus eliminating the concern of reduced potency.166 In contrast, in the case of CDR region deamidation, although the rate of deamidation may be controlled by appropriate process controls and formulation, the risk of continuous deamidation and loss of potency in vivo means that this risk cannot be mitigated.3

Conclusions

Developability assessment has been recognized as a critical step that should occur early in the process of selecting a drug candidate for development. The candidate is selected based on a thorough evaluation using in silico assessment with the aid of computational approaches and experimental data from extended characterization and forced degradation. Candidates with the most favorable biochemical and biophysical properties, and thus lower inherent risks, are selected for further development. Knowledge gained from developability assessments will also help guide process and product development to reduce timelines and resource consumption, thus providing affordable and high-quality mAb therapeutics to patients.

Abbreviations

- AC-SINS

Affinity capture self-interaction nanoparticle spectroscopy

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- ANS

1-anilino-naphthale-nesulfonate

- Asn

Asparagine

- Asp

Aspartate

- AUC

Analytical ultracentrifugation

- BLI

Biolayer interferometry

- C1q

Component of complement

- CDC

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity

- CDR

Complementarity-determining region

- CE

Capillary electrophoresis

- CIC

Cross-interaction chromatography

- cIEF

Capillary isoelectric focusing

- CMC

Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls

- Cys

Cysteine

- CZE

Capillary zone electrophoresis

- DLS

Dynamic light scattering

- DSC

Differential scanning calorimetry

- DSF

Differential scanning fluorimetry

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- Gal

Galactose

- Gln

Glutamine

- Glu

Glutamate

- Gly

Glycine

- HCP

Host cell protein

- HIC

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography

- HILIC

Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

- HMW

High molecular weight

- kDa

Kilodalton

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- LMW

Low molecular weight

- IEX

Ion exchange chromatography

- Lys

Lysine

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- Met

Methionine

- MFI

Micro-flow imaging

- MO

Membrane osmometry

- MOA

Mechanism of action

- NGNA

N-glycolylneuraminic acid

- PD

Pharmacodynamics

- PD

Pharmacokinetics

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

- QbD

Quality by design

- SAP

Spatial-aggregation propensity

- SC

Subcutaneous

- SCX

Strong cation exchange

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEC

Size exclusion chromatography

- SIC

Self-interaction chromatography

- SLS

Static light scattering

- Trp

Tryptophan

- Tyr

Tyrosine

- UF/DF

Ultrafiltration/Diafiltration

- WCX

Weak cation exchange

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Lavoisier A, Schlaeppi JM.. Early developability screen of therapeutic antibody candidates using Taylor dispersion analysis and UV area imaging detection. MAbs. 2015;7:77–83. doi: 10.4161/19420862.2014.985544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson CL, Devine PW, Phillips JJ, Higazi DR, Lloyd C, Popovic B, Arnold J, Buchanan A, Lewis A, Goodman J, et al. Engineering the surface properties of a human monoclonal antibody prevents self-association and rapid clearance in vivo. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38644. doi: 10.1038/srep38644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang X, Xu W, Dukleska S, Benchaar S, Mengisen S, Antochshuk V, Cheung J, Mann L, Babadjanova Z, Rowand J, et al. Developability studies before initiation of process development: improving manufacturability of monoclonal antibodies. MAbs. 2013;5:787–794. doi: 10.4161/mabs.25269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strohl WR. Current progress in innovative engineered antibodies. Protein Cell. 2018;9:86–120. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0457-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter PJ, Lazar GA. Next generation antibody drugs: pursuit of the ‘high-hanging fruit’. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:197–223. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplon H, Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2018. MAbs. 2018;10:183–203. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1415671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]