Abstract

Background

Pseudoprogression is a diagnostic challenge in early posttreatment glioblastoma. We therefore developed and validated a radiomics model using multiparametric MRI to differentiate pseudoprogression from early tumor progression in patients with glioblastoma.

Methods

The model was developed from the enlarging contrast-enhancing portions of 61 glioblastomas within 3 months after standard treatment with 6472 radiomic features being obtained from contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging, and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) maps. Imaging features were selected using a LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) logistic regression model with 10-fold cross-validation. Diagnostic performance for pseudoprogression was compared with that for single parameters (mean and minimum ADC and mean and maximum CBV) and single imaging radiomics models using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC). The model was validated with an external cohort (n = 34) imaged on a different scanner and internal prospective registry data (n = 23).

Results

Twelve significant radiomic features (3 from conventional, 2 from diffusion, and 7 from perfusion MRI) were selected for model construction. The multiparametric radiomics model (AUC, 0.90) showed significantly better performance than any single ADC or CBV parameter (AUC, 0.57–0.79, P < 0.05), and better than a single radiomics model using conventional MRI (AUC, 0.76, P = 0.012), ADC (AUC, 0.78, P = 0.014), or CBV (AUC, 0.80, P = 0.43). The multiparametric radiomics showed higher performance in the external validation (AUC, 0.85) and internal validation (AUC, 0.96) than any single approach, thus demonstrating robustness.

Conclusions

Incorporating diffusion- and perfusion-weighted MRI into a radiomics model improved diagnostic performance for identifying pseudoprogression and showed robustness in a multicenter setting.

Keywords: diffusion-weighted imaging, dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging, glioblastoma, pseudoprogression, radiomics

Key Points

A multiparametric radiomics model improved diagnostic performance and had good generalizability and could therefore augment the role of diffusion and perfusion MRI in the differentiation of pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma.

Importance of the Study

Pseudoprogression is a diagnostic challenge in neuro-radiology, especially within the first 3-month early posttreatment stage following Stupp treatment protocols for glioblastoma. A multiparametric radiomics model improved diagnostic performance and had good generalizability, and could therefore augment the role of diffusion and perfusion MRI in the differentiation of pseudoprogression from early tumor progression in patients with glioblastoma.

Determining the time point of tumor progression is crucial in the management of patients with glioblastoma who are in their early posttreatment stage.1 An incorrect diagnosis of tumor progression can lead to erroneous termination of successful treatment and negatively influence survival. Furthermore, an incorrect diagnosis could result in the inclusion of inappropriate patients in clinical trials. Pseudoprogression is still a challenging issue in both radiology and clinical practice, occurring in about 20% of high-grade glioma patients treated with adjuvant radiation plus temozolomide (TMZ).2 Pathological confirmation is the gold standard for the diagnosis of pseudoprogression but it is not commonly applicable, and it may take several months before pseudoprogression can be clearly distinguished from early tumor progression (ETP) on follow-up imaging,3 thus delaying a timely diagnosis.

Advanced MRI protocols involving diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) imaging show potential for distinguishing between these two conditions. Previous studies reported that recurrent tumors exhibit significantly lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values than radiation necrosis,4,5 and suggest histogram analysis of ADC as a promising parameter.6 Cerebral blood volume (CBV) has also been found to be particularly useful for diagnosing pseudoprogression,7,8 with sensitivity and specificity levels as high as 81.5% and 77.8%,8 respectively. However, single parameter approaches are limited in their ability to depict the heterogeneous nature of posttreatment glioblastomas, where tumor recurrence and radiation necrosis frequently coexist.9

Radiomics is an emerging field that converts imaging data into a high dimensional feature space using an automated data mining algorithm.10,11 Radiomics approaches can reflect the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of brain tumors, using clinically assessable commonly performed T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI.10 Radiomics studies in neuro-oncology have shown the potential to discover hidden information that was inaccessible with single parameter approaches in patients with glioblastomas; they can improve estimating prognoses12,13 and determination of treatment response to anti-angiogenic therapy.12 However, few studies have focused on differentiating pseudoprogression from ETP in patients with glioblastoma, a task that has significant implications in clinical practice.

We hypothesized that a high-throughput feature vector obtained from ADC and CBV maps could improve the diagnostic performance for pseudoprogression over that of conventional MRI data, by reflecting biologic information of tumor aggressiveness and vascularity at an early posttreatment stage of within 3 months. Also, we tried to validate the multiparametric MR radiomics model using fully independent validation set to provide robustness across heterogeneous imaging acquisition protocols. Thus, the purpose of this study was to develop and validate a radiomics model using multiparametric MRI to facilitate differentiation between pseudoprogression and ETP in patients with glioblastoma.

Materials and Methods

Study Patients

Our institutional review board approved this retrospective study, and the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. We searched the electronic database of the Department of Radiology at our tertiary center and retrospectively reviewed the records of patients between March 2011 and March 2017. We identified 238 consecutive patients who were pathologically confirmed as having glioblastoma and who subsequently received standard concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT) from Stupp et al14 after surgery at our institution. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (i) new histopathological diagnosis of a de novo glioblastoma according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria; (ii) CCRT with TMZ and 6 cycles of adjuvant TMZ performed after surgical resection or biopsy; (iii) baseline multiparametric MRI including contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging (CE-T1WI), FLAIR, DWI, and DSC imaging performed within 6 months (mean, 18.9 wk; range, 12.1–24.7 wk) after surgery or biopsy; (iv) newly developed or enlarging (>25%) and measurable contrast-enhancing lesions within 12 weeks of completing CCRT on MRI15; and (v) sequential follow-up contrast-enhanced MRI after completion of adjuvant TMZ to confirm the final diagnosis of pseudoprogression or ETP. Measurable contrast-enhancing lesions were defined as bidimensionally enhancing lesions with 2 perpendicular diameters of at least 10 mm, being visible on 2 or more axial slices. Patients were excluded if (i) the DWI or DSC sequence was not performed during the baseline MRI (n = 116), (ii) the residual contrast-enhancing lesion was unmeasurable in the baseline MRI (n = 13), (iii) there was no evidence of an enlarging contrast-enhancing lesion within 12 weeks of completing CCRT, which suggested a stable or favorable response to CCRT (n = 41), (iv) the quality of the baseline MRI was inadequate for image analysis (n = 1), or (v) patients were lost to follow-up (n = 6).

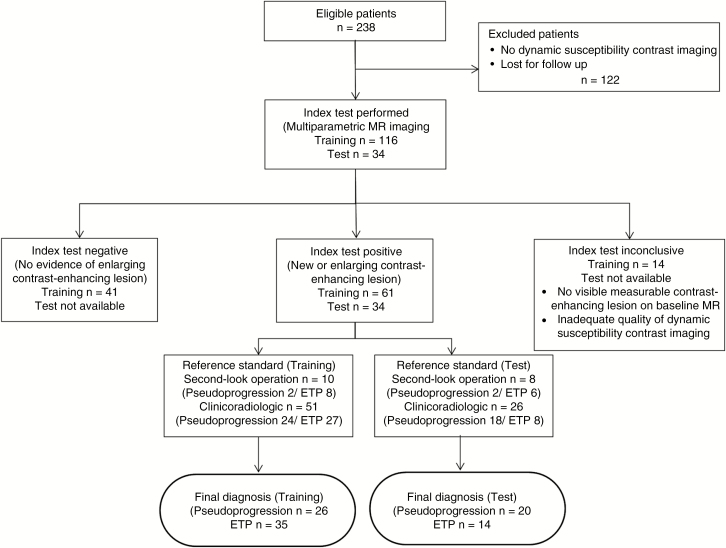

Therefore, 61 consecutive patients (mean age, 58 y, range 34–83; 38 [62%] male) were included in the study (Fig. 1). This cohort was used as a training set to develop a radiomics model for diagnosing pseudoprogression in patients with treated glioblastoma. Identical inclusion criteria were applied to identify 34 novel patients at another tertiary center (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) for the external validation of the model. The clinical and imaging characteristics of all patients were retrospectively assessed. The clinical characteristics of the patients included sex, age at diagnosis, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status, and the extent of surgical treatment of the tumor (gross total resection, partial resection, or biopsy).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the patient selection protocol and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. CCRT = concurrent chemoradiation therapy; TMZ = temozolomide; DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging; DSC = dynamic susceptibility contrast.

Reference Standard for Final Diagnosis

A final diagnosis of pseudoprogression and ETP was confirmed in 26 and 35 patients, respectively, in the training set, and in 20 and 14 patients, respectively, in the external validation set. In second-look operations, the pathological diagnoses included 2 pseudoprogression and 8 ETP cases in the training set and 2 pseudoprogression and 6 ETP cases in the external validation set. When second-look operations could not be performed, consecutive clinico-radiological diagnoses were made by consensus between a neuro-oncologist (J.H.K. with 26 years of experience in neuro-oncology practice) and a neuro-radiologist (H.S.K. with 18 years of experience in neuro-oncology imaging) according to the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology criteria.15 The clinico-radiological diagnoses classified the study population of the training set into 24 pseudoprogression cases and 27 ETP cases, and that of the external validation set into 18 pseudoprogression cases and 8 ETP cases. A final diagnosis of pseudoprogression was made when there was an increase in contrast-enhancing lesions that subsequently regressed or became stable without any changes in the treatment for at least 6 months after surgery and completion of CCRT. Alternatively, a final diagnosis of ETP was made if enhancing lesions gradually increased on more than 2 subsequent follow-up MRI studies performed at 2- to 3-month intervals and required a prompt change in treatment.

MRI Protocol and Image Preprocessing

In the training set, all MRI studies were performed on a 3T unit (Achieve, Philips Medical Systems), using an 8-channel head coil. In the external validation set, MRI studies were performed on a different 3T unit (Signa Excite, GE Medical Systems).

The brain tumor imaging protocol at our institution included T2-weighted imaging, FLAIR imaging, T1-weighted imaging, DWI, CE-T1WI, and DSC perfusion MRI. The detailed acquisition protocols and image preprocessing methods for the training and validation cohorts are summarized in the Supplementary material.

For the 3D CE-T1WI and FLAIR data, signal intensity normalization was performed to reduce the variance in the T1-based signal intensity of the brain. We used the hybrid white-stripe method16 for intensity normalization using the ANTsR and WhiteStripe packages17,18 in R, which incorporates processes of the statistical principles of image normalization, preserves ranks among the tissues, and matches the intensity of the tissues without upsetting the natural balance of the tissue intensities.18 Before we performed the feature extraction, we excluded outliers from the image intensities of the ADC and CBV maps by excluding standard deviations ± 3 inside the region of interest.19

Segmentation was performed semi-automatically on the contrast-enhancing tumor region by a neuroradiologist (with 2 years of experience in neuro-oncology imaging) using segmentation threshold and region-growing segmentation algorithms, which were implemented by MITK software (www.mitk.org German Cancer Research Center).16 Finally, all segmented images were reevaluated and validated by an experienced neuroradiologist (with 18 years of experience in neuro-oncology imaging).

Radiomics Feature Extraction

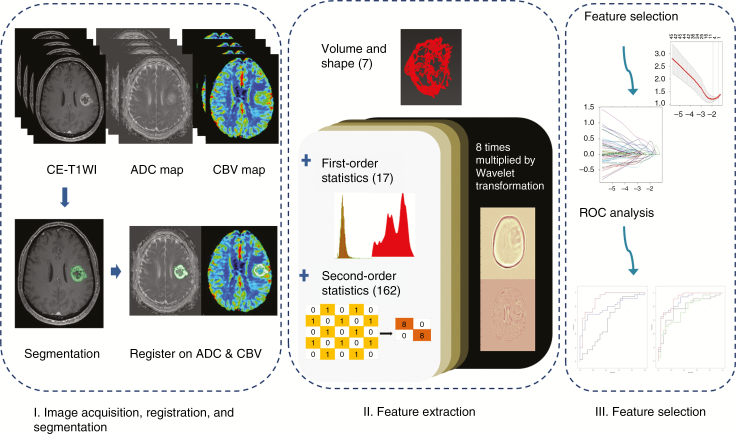

The overall process of the radiomics pipeline is shown in Fig. 2. The radiomic features were composed of 4 groups of features: 17 first-order features, 7 volume and shape features, 162 texture features, and 1432 wavelet-transformed features. The detailed information is in the Supplementary material S2. Thus, for each patient, 1618 radiomic features were derived from CE-T1WI, FLAIR, ADC, and CBV data. Finally, all radiomic features were z transformed for group comparisons. The processing time taken to extract the 1618 features was approximately 3 min per patient and the entire feature extraction algorithm was fully automated, which yielded identical features regardless of the operators.

Fig. 2.

Radiomics pipeline of the study. Part I includes image acquisition, registration, and segmentation. Signal intensity normalization is conducted for contrast-enhanced T1-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging. Part II includes extraction of radiomics features. Part III includes feature selection and modeling, with special consideration for high-dimensional data. The diagnostic performance is then calculated with the selected radiomics features. CE-T1WI = contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging; ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient; CBV = cerebral blood volume; ROC = receiver operating characteristic curve.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test and the chi-square test were used to assess differences between the training and validation sets regarding the demographic data and the prevalence of each classification category. For the training and external validation sets, Student’s t-test was used to assess differences in the imaging parameters between the pseudoprogression and ETP groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.3.3 statistical software.

Selection of significant radiomic features and model construction with the training set

We applied the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) in the training data to select the significant features with nonzero coefficients that can differentiate between pseudoprogression and ETP diagnoses. LASSO is a penalization method that shrinks all regression coefficients and sets the coefficients of many irrelevant features that have no discriminatory power between the classes exactly to zero.20,21 It was chosen because it has a small variance, is known to be suitable for analyzing large datasets of radiomics features in small samples, and is designed to avoid overfitting.21–23 To provide robust generalized performance of a model that best fits the observed data, 10-fold cross-validation with a minimum criterion was applied, with these folds b randomly picked. This 10-fold was chosen as it is the default option in LASSO. After the feature selection, the radiomics model was constructed using a generalized linear model as a classifier and diagnostic performance of the model was compared.

To further evaluate the significance of the non-wavelet transformed features, a radiomics model using 186 non-wavelet features was separately constructed. The feature selection and classification method was otherwise the same as that described above.

Model performance and validation

The area under the curve (AUC) from a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was calculated to test the diagnostic performance of the radiomics models. The optimal thresholds of the AUCs were determined by maximizing the sum of the sensitivity and specificity values calculated for differentiation of pseudoprogression from ETP. The definitions of accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity for correctly diagnosing pseudoprogression are as follows (TP: true positive; TN: true negative; FP: false positive; FN: false negative):

To develop an exportable and generalizable radiomics model, the model was built using a training cohort and then validated with an external validation cohort.

Comparison of diagnostic performance

The diagnostic performance of the multiparametric MR radiomics model was compared with those of the single-layered radiomics models constructed using only conventional MRI (CE-T1WI and FLAIR imaging), ADC map, or CBV map.

Also, the diagnostic performance of the multiparametric MR radiomics model was compared with that of a non-radiomics approach using CBV and ADC. The mean and maximum CBV values and the mean and minimum ADC values were chosen as single parameters for comparisons. Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the P-values for multiple comparisons. A Bonferroni-corrected significance level of P < 0.017 was used for comparison between the multiparametric radiomics model and 3 single radiomics models, and a value of P < 0.0125 was used between the multiparametric radiomics model and the 4 non-radiomics approaches.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis was performed to determine any associations between diagnostic group and survival. Overall survival was measured from the date of surgery to death, and a log-rank test was employed to compare the pseudoprogression versus the ETP group. Patients who were alive at last evaluation (May 30, 2018) were censored. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for adjustment of age, sex, and KPS score.

A pilot internal validation from a prospective registry

To further validate our model, we tested it on an additional 23 patients between July 2017 and March 2018, by retrospective enrollment from a prospective brain glioma registry (NCT02619890) of patients for whom full molecular data of IDH mutation status and MGMT promoter methylation status were available. The imaging protocols were consistent with the training data.

Results

Patient Demographics

The clinical characteristics of the training and validation cohorts are summarized in Table 1. Of the 61 study patients in the training set, 26 (42.6%) were classified as pseudoprogression and 35 (57.4%) as ETP cases. The 34 patients in the external validation set consisted of 20 (58.8%) pseudoprogression and 14 (41.2%) ETP cases. Among those patients for whom MGMT promoter methylation status information was available, the pseudoprogression patients showed a significantly higher rate of methylated MGMT promoter than the ETP patients, in both the training (P = 0.001) and external validation sets (P = 0.02). There were no significant differences between the patients with pseudoprogression and ETP in regard to age, sex, baseline KPS score, IDH mutation status, extent of surgery, and mean time interval between the operation and imaging study, in either the training or the external validation set.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Variables | Training Set | External Validation Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP (n = 26) | ETP (n = 35) | P | PP (n = 20) | ETP (n = 14) | P | |

| Age, y* | 57.1 ± 10.6 | 58.6 ± 10.6 | 0.89 | 61.3 ± 11.6 | 63.9 ± 12.1 | 0.60 |

| No. of female patients | 10 (38.5%) | 13 (37.1%) | 0.84 | 5 (15.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.07 |

| KPS ≥70 | 21 (80.8%) | 28 (80.0%) | 0.88 | 17 (85.0%) | 11 (78.6%) | 0.36 |

| IDH-wild type | 23 (88.5%) | 34 (97.1%) | 0.21 | 20 (100%) | 14 (100%) | 1 |

| MGMT promoter status (methylated/ unmethylated/NA) | 5/5/16 | 2/12/21 | 0.001 | 12/7/1 | 5/5/5 | 0.02 |

| Surgical extent | 0.09 | 0.81 | ||||

| Biopsy | 0 | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | ||

| Partial resection | 7 (26.9%) | 13 (37.1%) | 8 (40.0%) | 5 (35.7%) | ||

| Gross total resection | 19 (73.1%) | 22 (62.9%) | 8 (40.0%) | 6 (42.9%) | ||

| Mean time interval between the operation and imaging, days | 103.8 ± 14.4 | 100.0 ± 26.0 | 0.10 | 96.5 ± 26.0 | 107.2 ± 28.9 | 0.78 |

| Adjuvant treatment for ETP | ||||||

| TMZ + avastin | - | 13 | - | - | 1 | - |

| TMZ/avastin monotherapy | - | 6/8 | - | - | 8/4 | - |

| Others | - | 8 | - | - | 1 | - |

Note: Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Numbers in parentheses are percentage. Abbreviations: PP = pseudoprogression, NA = not available. Others include irinotecan monotherapy, vincristine monotherapy, or their combination with avastin.

Feature Extraction

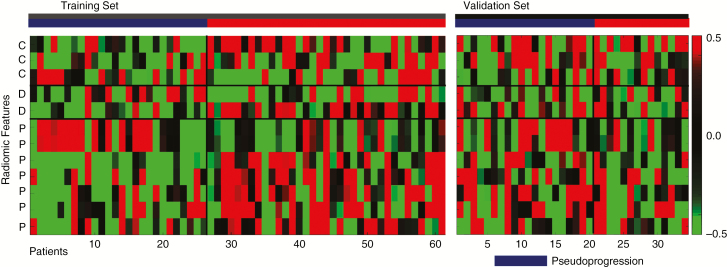

A total of 6472 features were extracted from the multiparametric MRI data (1618 features each from CE-T1WI, FLAIR, ADC, and CBV). Table 2 lists the 12 significant radiomics features for differentiating between pseudoprogression and ETP, as identified using the LASSO penalization in the training cohort (S3 Supplementary Fig. 1). Three features were obtained from conventional MR imaging (2 from CE-T1WI and 1 from FLAIR), 2 features from diffusion MR imaging, and 6 features from perfusion MR imaging. Of the features obtained from conventional MRI, 2 were first-order features (covered image intensity range and standard deviation) and 1 was a Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) feature (standard deviation of correlation). From the ADC, 1 feature was a Gray-Level Run-Length Matrix (GLRLM) feature (mean of long run low gray-level emphasis) and the other was a GLCM feature (mean of correlation). From the perfusion MR imaging, 6 selected features were GLCM based (1 mean of inverse difference moment normalized, 1 inverse difference normalized, 2 Haralick correlations, and 2 difference averages), while 1 was a first-order feature (sum of intensities). In particular, the Haralick correlations (LLH, GLCM) obtained from the CBV images were ranked as the most superior features for differentiating between pseudoprogression and ETP. Fig. 3 demonstrates the heatmap of pseudoprogression and ETP in the training and external validation sets using the selected features.

Table 2.

List of significant multiparametric MR radiomic features to differentiate between pseudoprogression and early tumor progression using LASSO logistic regression

| Order | Wavelet-Transformation | Imaging Parameter | Radiomic Feature | Feature Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Original | CE-T1WI | Covered image intensity range | First-order |

| 2 | LLL | CE-T1WI | Correlation (SD) | GLCM (2) |

| 3 | Original | FLAIR | SD (standard deviation) | First-order |

| 4 | LLL | ADC | Long run low gray-level emphasis (mean) | GLRLM |

| 5 | LLH | ADC | Correlation (mean) | GLCM (1) |

| 6 | HHL | CBV | Inverse difference moment normalized (mean) | GLCM (3) |

| 7 | HHL | CBV | Inverse difference normalized (mean) | GLCM (3) |

| 8 | Original | CBV | Sum of intensities | First-order |

| 9 | LLL | CBV | Haralick correlation (mean) | GLCM (2) |

| 10 | LLH | CBV | Haralick correlation (mean) | GLCM (2) |

| 11 | LHL | CBV | Difference average (mean) | GLCM (2) |

| 12 | LHL | CBV | Difference average (mean) | GLCM (2) |

Note: Numbers in parentheses represent 2 or 3 consecutive voxels in the texture analysis.

Abbreviations: H = high-pass filter; L = low-pass filter.

Fig. 3.

Heatmap of the significant radiomics features. Each column corresponds to one patient, and each row corresponds to the z-scores of the normalized radiomics features. Twelve radiomics features were selected, 3 from conventional MRI (C), 2 from diffusion MRI (D), and 6 from perfusion MRI (P). The heatmap is grouped for the training and external validation sets, and the pseudoprogression (dark blue) versus early tumor progression (red) groups via radiomics analysis. Note: C = conventional MR radiomics feature; D = diffusion weighted MR radiomics features; P = perfusion-weighted MR radiomics features

Constructing a Multiparametric MR Radiomics Model from the Training Set

Table 3 summarizes the diagnostic performance of the radiomics features in the training and external validation sets. The multiparametric MR radiomics approach showed the highest performance, with AUC of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.82–0.98).

Table 3.

Comparison of diagnostic performance between multiparametric MR radiomics models and other approaches in the training and validation sets

| Training Set | External Validation Set | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | AUC | P* | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Combined radiomics model | Multiparametric MR (conventional + diffusion + perfusion MR) |

0.90 (0.82, 0.98) |

91.4% | 76.9% | 0.85 (0.71, 0.99) |

71.4% | 90.0% | |

| Single radiomics model | Conventional MR | 0.76 (0.63, 0.88) |

0.012 | 51.4% | 88.5% | 0.74 (0.67, 0.97) |

78.6% | 75.0% |

| Diffusion MR | 0.78 (0.66, 0.90) |

0.014 | 77.1% | 76.9% | 0.53 (0.33, 0.73) |

100% | 20% | |

| Perfusion MR | 0.88 (0.80, 0.97) |

0.427 | 65.7% | 96.2% | 0.71 (0.52, 0.89) |

85.7% | 60.0% | |

| Single parameter | Mean ADC | 0.57 (0.42, 0.73) |

<0.001 | 77.1% | 46.2% | 0.57 (0.38, 0.77) |

78.6% | 45.0% |

| Minimum ADC | 0.61 (0.46, 0.76) |

<0.001 | 71.4% | 57.7% | 0.50 (0.30, 0.70) |

50.0% | 65.0% | |

| Mean CBV | 0.77 (0.64, 0.87) |

<0.001 | 65.7% | 84.6% | 0.58 (0.40, 0.75) |

100.0% | 30.0% | |

| Maximum CBV | 0.79 (0.66, 0.88) |

<0.001 | 62.9% | 92.3% | 0.58 (0.40, 0.75) |

78.6% | 45.0% | |

Note: Numbers in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

*P-value refers to the significance among the differences of the AUCs between the multiparametric MR radiomics model and the other model. The Bonferroni-corrected significance level of P < 0.017 was used when comparing between a multiparametric MR radiomics model and 3 single radiomics models, and P < 0.0125 between a multiparametric radiomics model and 4 single parameter approaches.

This multiparametric radiomics model was compared with the single radiomics and single parameter approaches. The multiparametric MR radiomics model showed a significant increase in performance over the single radiomics models based on conventional (AUC, 0.76; P = 0.012) or diffusion-weighted (AUC, 0.78; P = 0.014) imaging. The multiparametric MR radiomics model also showed better performance than the perfusion-weighted MR-based model (AUC, 0.88), but the difference was not significant.

When compared with the single parameter approach, the multiparametric radiomics model outperformed all of the single parameters of mean ADC (AUC, 0.57; P < 0.001), minimum ADC (AUC, 0.61; P < 0.001), mean CBV (AUC, 0.77; P < 0.001), or maximum CBV (AUC, 0.79; P < 0.001).

Model Performance with the External Validation Set

In the external validation, the multiparametric MR radiomics model remained the highest performer, with AUC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.71–0.99), sensitivity of 68.3%, specificity of 74.1%, and accuracy of 72.3% (Table 3).

Meanwhile, the conventional MR radiomics model demonstrated an AUC of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.67–0.97), with sensitivity of 65.9%, specificity of 78.1%, and accuracy of 73.4%. The diffusion MR radiomics model showed an AUC of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.33–0.73), with sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 20%, and accuracy of 47.0%. The perfusion MR radiomics had an AUC of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.52–0.89), with sensitivity of 51.3%, specificity of 53.9%, and accuracy of 57.5%. Though the performance of all radiomics models dropped with the external validation data in comparison with the training data, the trend of improved diagnostic performance with multiparametric MRI was maintained in the external validation.

When compared with the single parameter approaches, the multiparametric MR radiomics model outperformed any of the single parameters of mean ADC (AUC, 0.57; P < 0.001), minimum ADC (AUC, 0.50; P < 0.001), mean CBV (AUC, 0.57; P < 0.001), or maximum CBV (AUC, 0.61; P < 0.001).

Model Performance Using the Non-Wavelet Features

A total of 744 non-wavelet features were analyzed, 186 features for each imaging sequence. The significant non-wavelet radiomics features for differentiating between pseudoprogression and ETP included 3 from conventional imaging (1 from CE-T1WI and 2 from FLAIR), 2 from DWI, and 1 from perfusion MRI (S4. Supplementary Table 2). The multiparametric non-wavelet MR radiomics model showed higher diagnostic performance (AUC, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73–0.95) than the single imaging technique radiomics models based on conventional MRI (AUC, 0.72; 95% CI: 0.58–0.85), DWI (AUC, 0.82; 95% CI: 0.70–0.93), or perfusion-weighted MRI (AUC, 0.78; 95% CI: 0.67–0.90) (S5. Supplementary Table 3). The performances on the external validation set showed the same trends, with the highest diagnostic performance with the multiparametric MR radiomics model with AUC of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.69–0.97).

Survival Analysis on the Training Set

The median follow-up time was 474 days (interquartile range, 344–693 days), and the median survival was 536 days in the pseudoprogression group and 383 days in the ETP group. There was a significant difference in survival between the 2 groups (log-rank test, P = 0.01). A multivariate Cox regression was performed on the clinical predictors, including age, KPS score, surgical extent, and diagnostic group of pseudoprogression or ETP, and showed that only ETP (P = 0.0004) was a significant clinical predictor of shorter survival (S6. Supplementary Table 4).

A Pilot Result from the Prospective Glioma Registry

There were 16 patients with ETP and 7 patients with pseudoprogression. The reference standard was a second-look operation in 6 cases in the ETP group, while it was clinical-radiologic follow-up in the others. IDH-wildtype was observed in all patients, and methylated MGMT was observed in 29.4% (5 of 17 cases) of the ETP group and 66.6% (4 of 6 cases) of the pseudoprogression group (S7. Supplementary Table 5).

The performance of the multiparametric MR radiomics model remained the highest, with AUC of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.88–1.00; accuracy: 95.6%), compared with conventional (AUC, 0.82), diffusion MR (AUC, 0.61), or perfusion MR (AUC, 0.91) radiomics models (S8. Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that incorporating diffusion- and perfusion-weighted MRI into a radiomics model improves the diagnostic performance for distinguishing between pseudoprogression and ETP in glioblastoma patients with contrast-enhancing lesions during the early posttreatment stage. The multiparametric MR radiomics model showed higher performance than any single imaging technique radiomics model or any single ADC or CBV parameter. This radiomics model was validated externally and showed robustness. Thus, adding diffusion- and perfusion-weighted MRI into a radiomics model, especially perfusion-weighted MRI, may become a better approach in the challenging situation of diagnosing pseudoprogression than utilizing single ADC and CBV values, or conventional MR radiomics models.

Several studies have shown the potential use of ADC and CBV as a diagnostic parameter to differentiate between pseudoprogression and ETP in glioblastomas.4–8,24,25 However, single parameter is only capable of providing a probability in one direction,26 limiting the comprehensive characterization of posttreatment glioblastoma. Multiparametric tissue characterization has been attempted with pattern analysis27,28 and voxel-based clustering,26 but such unsupervised learning approaches do not directly lead to discriminatory analysis or a specific diagnosis. The radiomics approach, on the other hand, can offer improved discriminatory power by demonstrating voxel-based heterogeneity and utilizing supervised learning with binary classification.

The previous MRI radiomics approaches have been confined to conventional MRI of CE-T1WI or FLAIR,12,29–32 and few studies have introduced a radiomics model utilizing diffusion- or perfusion-weighted MRI to differentiate between pseudoprogression and ETP. Advanced MRI may contain biological information of the tumor by DWI reflecting hypercellularity4,5 and perfusion-weighted imaging reflecting hypervascularity.7,24 In posttreatment glioblastomas, a wide spectrum of histological features range from necrosis to hypercellular recurrent tumor components, which can result in heterogeneity at ADC.6 DSC MRI has been suggested to be useful in diagnosing ETP as quantifiable differences occur in the tissue vasculature after treatment, with higher levels in ETP due to angiogenesis of the tumor.7,24,25 Moreover, the perfusion MR radiomics alone showed sufficient diagnostic performance comparable to the multiparametric MR approach in the training set, which further emphasizes the role of perfusion MRI in diagnosing ETP.

A finding of note is that the radiomics model showed robustness even when wavelet features were excluded. The performance of the model did, however, decrease, indicating that wavelet-transformed features improve the radiomics diagnosis of pseudoprogression. The most relevant imaging feature among the selected descriptors was GLCM in the perfusion MRI. GLCM is a texture-analysis method that calculates how often pairs of pixels with specific values and in a specified spatial relationship occur in an image, and it is known to reflect the heterogeneity of the tumor.33 Also, texture analysis of CBV has been shown to correlate with the prognoses and recurrences of glioblastomas.34,35 Our results are in line with those of previous studies that texture analysis of hemodynamic parameters of the CBV may reflect hypervascularity and neoangiogenesis of ETP, distinguishing it from pseudoprogression.

Lack of standardization of the acquisition protocols might be an obstacle that prevents its use as a biomarker in multicenter practices as well as in the radiomics approach. Our model has strength in that it was validated by the external cohort under heterogeneous acquisition protocols. Though the diagnostic performance of each imaging procedure slightly differed between the 2 centers, the multiparametric MR radiomics showed the highest performance concordantly. Interestingly, the diagnostic performance dropped with the ADC and CBV, but remained relatively robust with conventional MR radiomics. This may come from different ratios of pseudoprogression and ETP between the 2 cohorts, which may affect AUC value.36 Also, we assume that this was attributed to signal normalization that was performed for conventional MR radiomics during preprocessing (WhiteStripe), which was not done for diffusion- or perfusion-weighted MRI. Though we utilized quantitative maps of ADC and CBV, radiomics features may become affected from different imaging acquisition protocols.37–39 Further studies on the effect of signal normalization of ADC and CBV across different centers are warranted.

This study had several limitations in addition to those due to its retrospective nature. First, the accuracy of the multiparametric MR radiomics model was moderate (72%) in the external validation, which may not be sufficient to yield a reliable clinical performance. This may be due to the small size of the cohort, especially that of the external validation dataset, which limits statistical power of our data. Also, the stability of the radiomics model needs to be further improved with a larger training set with multicenter enrollment using different MR protocols. Second, there was a relatively high fraction of pseudoprogression. Previous studies reported an incidence of pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma of around 11.4% up until the 12-month post-radiation scan, and 13.3% (6 of 45 patients) after 4 weeks.40 The relatively high fraction of patients with pseudoprogression in the present study can be explained by the fact that the denominator was not all glioblastoma patients in the follow-up, but the sum of the patients in the 2 groups, which were defined in the inclusion criteria as those showing newly developed or enlarging (>25%) and measurable contrast-enhancing lesions within 12 weeks of completing CCRT on MRI. When all follow-up patients were considered in the flowchart, the incidence dropped to 22.4% (26 of 116 patients). This incidence rate would be lower still if patients who did not undergo multiparametric MRI were included. Third, although we performed the radiomics analysis using different 3T scanning parameters, validation with a 1.5T scanner is required to incorporate the radiomics model as a multicenter imaging biomarker. Fourth, the preprocessing methods in this study have room for improvement. Spline interpolation generally yields better registration quality than trilinear interpolation, and could positively affect the results. Furthermore, the normalization method for CBV could potentially be more robust and user independent if an automatic segmentation method were used, such as FAST (FMRIB’s automated segmentation tool). Such updates to the methods need to be evaluated in future work. Fifth, because the radiomics approach is a data-driven analysis, it is difficult to fully understand the biological meaning of the numerical data derived from the analysis. Also, radiomics analysis requires labor-intensive image processing and data analysis procedures. Although it took an average of about 8 minutes to extract the data features of each patient in our study, further advances to reduce the time cost and simplify the analytical process might be beneficial to clinical practice. Finally, the model should be independently and prospectively verified, preferably in a multicenter setting. If properly verified, the model could become a useful tool to help in the early discrimination of pseudoprogression and tumor progression, which would prevent early discontinuation of successful therapy or unnecessary prolongation of unsuccessful therapy.

In conclusion, incorporating diffusion- and perfusion-weighted MRI into a radiomics model improved diagnostic performance for identifying pseudoprogression and showed robustness in a multicenter setting.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant number: NRF-2017R1A2A2A05001217) and by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (1720030).

Supplementary Material

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Authorship statement. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

J.Y.K.: Manuscript writing, statistical analysis

J.E.P.: Manuscript editing, supervised image segmentation, statistical analysis

Y.J.: Image postprocessing, data provision, and informatics software support

W.H.S.: Supervised image postprocessing

S.J.N.: Molecular and pathologic analysis

J.H.K.: Clinical/oncologic database curation and oversight

R-E.Y., S.H.C.: Database construction and data provision

H.S.K.: Database construction, clinical oversight, conceptual feedback, and project integrity

References

- 1. Stuplich M, Hadizadeh DR, Kuchelmeister K, et al. Late and prolonged pseudoprogression in glioblastoma after treatment with lomustine and temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):e180–e183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kruser TJ, Mehta MP, Robins HI. Pseudoprogression after glioma therapy: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(4):389–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hygino da Cruz LC, Rodriguez I, Domingues RC, Gasparetto EL, Sorensen AG. Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse: imaging challenges in the assessment of posttreatment glioma. AJNR Am J Neurorad. 2011;32(11):1978–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hein PA, Eskey CJ, Dunn JF, Hug EB. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the follow-up of treated high-grade gliomas: tumor recurrence versus radiation injury. AJNR Am J Neurorad. 2004;25(2):201–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asao C, Korogi Y, Kitajima M, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of radiation-induced brain injury for differentiation from tumor recurrence. AJNR Am J Neurorad. 2005;26(6):1455–1460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chu HH, Choi SH, Ryoo I, et al. Differentiation of true progression from pseudoprogression in glioblastoma treated with radiation therapy and concomitant temozolomide: comparison study of standard and high-b-value diffusion-weighted imaging. Radiology. 2013;269(3):831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barajas RF Jr, Chang JS, Segal MR, et al. Differentiation of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme from radiation necrosis after external beam radiation therapy with dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;253(2):486–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kong DS, Kim ST, Kim EH, et al. Diagnostic dilemma of pseudoprogression in the treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastomas: the role of assessing relative cerebral blood flow volume and oxygen-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation status. AJNR Am J Neurorad. 2011;32(2):382–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jung V, Romeike BF, Henn W, et al. Evidence of focal genetic microheterogeneity in glioblastoma multiforme by area-specific CGH on microdissected tumor cells. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58(9):993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1234–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kickingereder P, Gotz M, Muschelli J, et al. Large-scale radiomic profiling of recurrent glioblastoma identifies an imaging predictor for stratifying anti-angiogenic treatment response. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(23):5765–5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou H, Vallières M, Bai HX, et al. MRI features predict survival and molecular markers in diffuse lower-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(6):862–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1963–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nolden M, Zelzer S, Seitel A, et al. The Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit: challenges and advances: 10 years of open-source development. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2013;8(4):607–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2033–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shinohara RT, Sweeney EM, Goldsmith J, et al. Statistical normalization techniques for magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage Clin. 2014;6:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Collewet G, Strzelecki M, Mariette F. Influence of MRI acquisition protocols and image intensity normalization methods on texture classification. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1996;58(1):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu TT, Chen YF, Hastie T, Sobel E, Lange K. Genome-wide association analysis by lasso penalized logistic regression. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2009;25(6):714–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hepp T, Schmid M, Gefeller O, Waldmann E, Mayr A. Approaches to regularized regression—a comparison between gradient boosting and the Lasso. Methods Inf Med. 2016;55(5):422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gui J, Li H. Penalized Cox regression analysis in the high-dimensional and low-sample size settings, with applications to microarray gene expression data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2005;21(13):3001–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lupo JM, Cha S, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Dynamic susceptibility-weighted perfusion imaging of high-grade gliomas: characterization of spatial heterogeneity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(6):1446–1454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hu LS, Baxter LC, Smith KA, et al. Relative cerebral blood volume values to differentiate high-grade glioma recurrence from posttreatment radiation effect: direct correlation between image-guided tissue histopathology and localized dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging measurements. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(3):552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Park JE, Kim HS, Goh MJ, Kim SJ, Kim JH. Pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma: assessment by using volume-weighted voxel-based multiparametric clustering of MR imaging data in an independent test set. Radiology. 2015;275(3):792–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verma R, Zacharaki EI, Ou Y, et al. Multiparametric tissue characterization of brain neoplasms and their recurrence using pattern classification of MR images. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(8):966–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hu X, Wong KK, Young GS, Guo L, Wong ST. Support vector machine multiparametric MRI identification of pseudoprogression from tumor recurrence in patients with resected glioblastoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(2):296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Qian X, Tan H, Zhang J, et al. Identification of biomarkers for pseudo and true progression of GBM based on radiogenomics study. Oncotarget. 2016;7(34):55377–55394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kickingereder P, Burth S, Wick A, et al. Radiomic profiling of glioblastoma: identifying an imaging predictor of patient survival with improved performance over established clinical and radiologic risk models. Radiology. 2016;280(3):880–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGarry SD, Hurrell SL, Kaczmarowski AL, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomic profiles predict patient prognosis in newly diagnosed glioblastoma before therapy. Tomography. 2016;2(3):223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chaddad A, Desrosiers C, Toews M. Radiomic analysis of multi-contrast brain MRI for the prediction of survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Conference proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual Conference 2016;2016:4035–4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Materka A, Strzelecki M.. Texture Analysis Methods—A Review. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee J, Jain R, Khalil K, et al. Texture feature ratios from relative CBV maps of perfusion MRI are associated with patient survival in glioblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(1):37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ion-Margineanu A, Van Cauter S, Sima DM, et al. Classifying glioblastoma multiforme follow-up progressive vs. responsive forms using multi-parametric MRI features. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knutsson L, van Westen D, Petersen ET, et al. Absolute quantification of cerebral blood flow: correlation between dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI and model-free arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shin W, Horowitz S, Ragin A, Chen Y, Walker M, Carroll TJ. Quantitative cerebral perfusion using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI: evaluation of reproducibility and age- and gender-dependence with fully automatic image postprocessing algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1232–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Conte GM, Castellano A, Altabella L, et al. Reproducibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI in the study of brain gliomas: a comparison of data obtained using different commercial software. Radiol Med. 2017;122(4):294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radbruch A, Fladt J, Kickingereder P, et al. Pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma: clinical relevance despite low incidence. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(1):151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.